Ali Ateya, Salah El-Bahnasi, Mohamed Hossam El-Din, Medhat El-Menabbawi, Tarek Torky

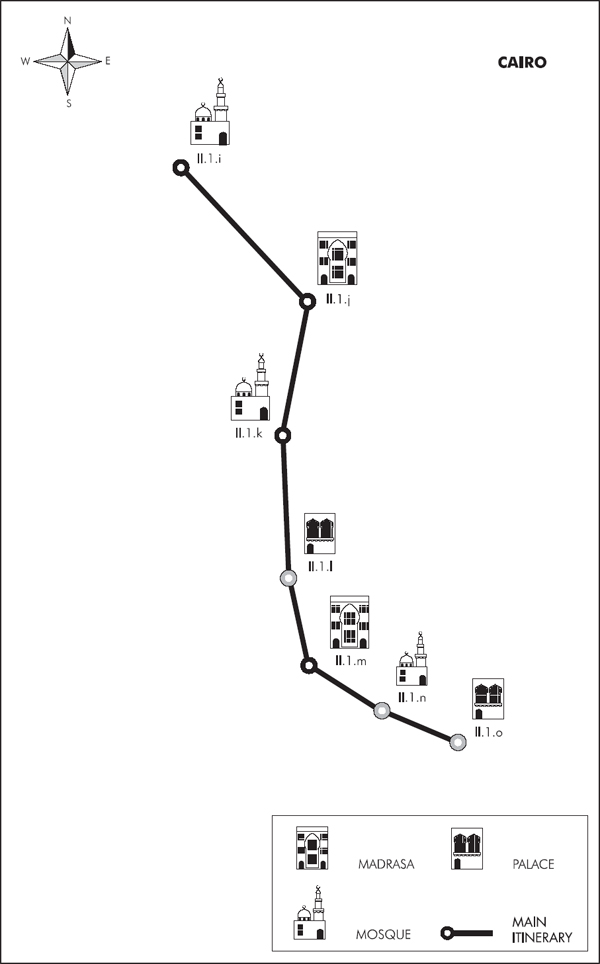

Second day

II.1.i Mosque of Sultan al-Mu’ayyad Shaykh

II.1.j Madrasa of Qujmas al-Ishaqi

II.1.k Mosque of al-Tunbugha al-Maridani

II.1.l Door to the House of Qaytbay in al-Razzaz (option)

II.1.m Madrasa of Umm al-Sultan Sha’ban

II.1.n Mosque of Aqsunqur (option)

II.1.o Palace of Alin Aq al-Husami (option)

II.1.i Mosque of Sultan al-Mu’ayyad Shaykh

This mosque is adjacent to the Fatimid Gate, Bab Zuwayla, at the southern end of al-Mu‘izz li-Din Allah Street.

Opening times: all day except during midday and afternoon prayers (12.00 and 15.00 in winter, 13.00 and 16.00 in summer). The building is currently being restored and visitors are not allowed inside.

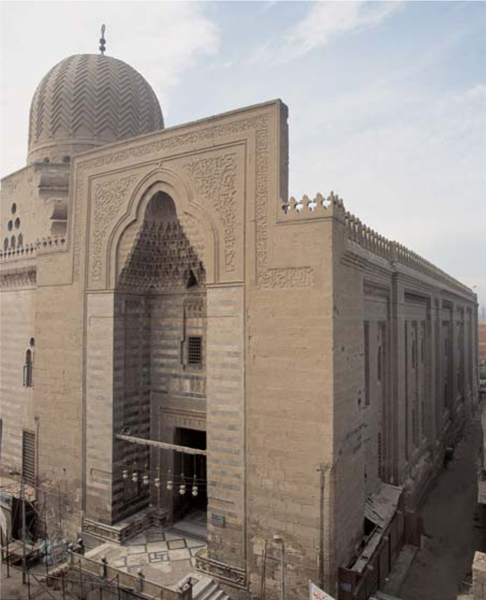

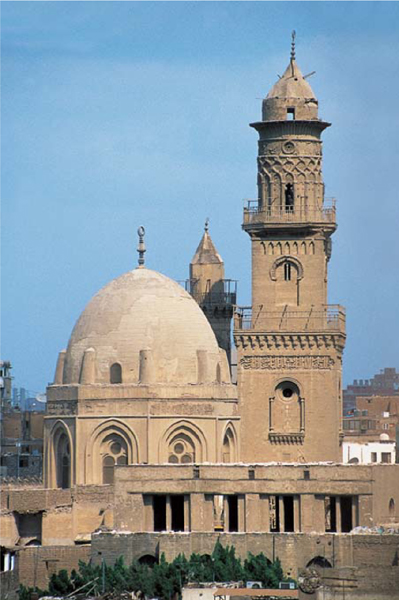

Sultan al-Mu’ayyad Shaykh had this mosque built on the site of the prison in which he had been confined while an amir under Sultan Farag Ibn Barquq. He vowed to turn the prison into a place of study and prayer should God ever bestow upon him the honour of ruling Egypt. In 818/1415 construction began. This vast pious foundation was to include a congregational mosque, three minarets, two mausoleums and a madrasa for the four rites for Sufi students. On al-Mu’ayyad Shaykh’s death, the building had not reached completion. It is one of Cairo’s largest mosques and when the Ottoman Sultan Salim I saw it, he is said to have exclaimed “It is indeed a building fit for kings”.

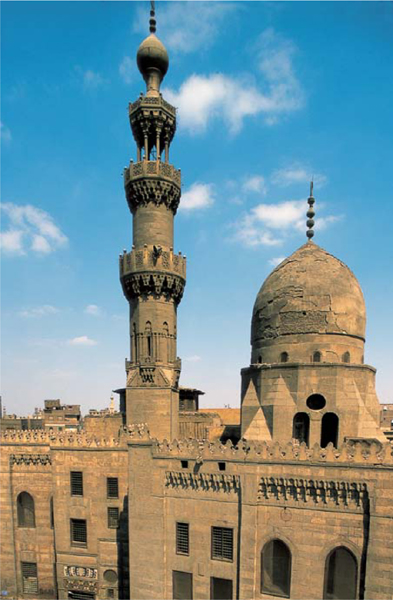

Mosque of Sultan al-Mu’ayyad Shaykh, entrance and dome, Cairo.

It has been called the mosque of sin by some historians due to the fact that some of its furnishings were taken from other buildings. Despite having spent enormous sums of money on the construction and furnishing of the building, when al-Mu’ayyad could not afford costly materials he expropriated them from other earlier foundations. In spite of paying for their removal, such practice was deemed illegal given that once a complex had been furnished, both its buildings and its fittings could no longer change hands. All the same he paid 500 dinars for the lamps and main entrance-door panels faced in bronze and inlaid with metal originally from the Sultan Hassan complex (I.1.g). The marble panels and friezes come from the qibla wall in the Mosque of Qusun and from other mosques and houses. Sultan al-Mu’ayyad made his amirs pay for the paintings in the mosque and the artisans for the expenses on carpentry and wood decoration.

The main entrance on the south east façade is decorated in alternating bands of black and white marble and crowned by a tri-lobed arch. Its deep recess is crowned with a vault of nine rows of muqarnas, all of which are enclosed in a rectangular frame rising above the cornice, characteristic of Iranian architectural gorigins. The door-jambs and the lintel of pink granite are framed in a white interlaced band with earthenware red and turquoise incrustations. The entrance leads to a derka, where a cross vault rises above it. To the right there is a passageway paved in marble leading to the mosque courtyard, in the centre of which an ablutions font replaces the old fountain. To the left we gain access to the mausoleum in which the Sultan and his oldest son Ibrahim are buried. The mihrab in the square mausoleum is decorated with marble and a dome resting on muqarnas pendentives rises above it. On the outside, the dome is decorated with the same horizontal zigzag design as the domes of the khanqa of Farag Ibn Barquq. The prayer hall was to be flanked on either side by a domed mausoleum, but only the tombs of the Sultan and his son are housed in such a way. The second mausoleum, set apart for the women and covered by a flat roof, is located to the south of the qibla hall, at the foot of one of the two minarets.

Of the three minarets along the southwest axis of the building, the western-most one collapsed. The other two, supported by the towers of Bab Zuwayla, also collapsed not long after being built in 842/1438; they were soon reconstructed.

With the use of the towers of Bab Zuwayla as the base for the two minarets, they dominate the skyline from a distance clearly visible from the Citadel. The two minarets with their octagonal section shafts and transitions each separated by a balcony resting on a muqarnas cornice, and gawsaq crowned with a bulbiform top standing 50 m. high above street level, have become a symbol of the city of Cairo.

Mosque of Sultan al-Mu’ayyad Shaykh, detail of the tri-lobed arch, Cairo.

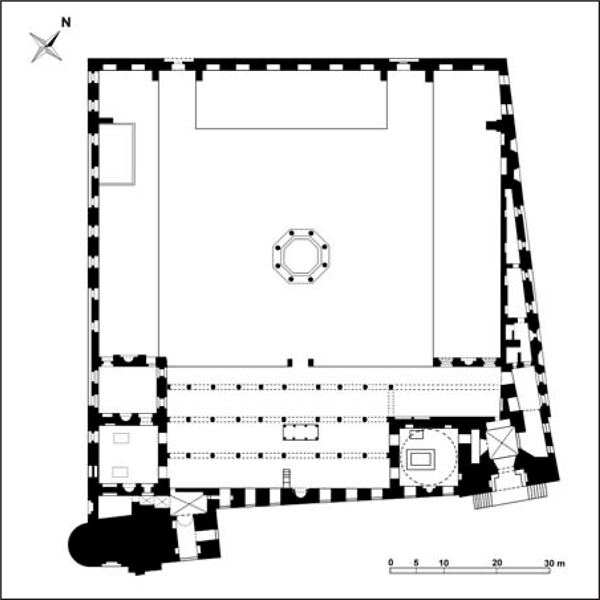

Mosque of Sultan al-Mu’ayyad Shaykh, plan, Cairo.

The mosque layout follows the lines of the traditional hypostyle mosque plan. The central courtyard was originally surrounded by four porticoes. Today only one remains, that of the qibla wall. Archaeological excavations have revealed that the other three sides comprised a double aisle divided by an arcade. Parallel to the qibla wall, three rows of marble columns uphold the richly decorated wooden ceiling. The walls around the sanctuary are covered by coloured marble panels, which originated from earlier buildings. The richest decoration was naturally reserved for the qibla wall. The high panelling at the base of the mihrab is divided into two areas by differing types of marble decoration and crowned by a frieze of paired colonettes in turquoise blue. To its right is the original wooden minbar; it is decorated in mother-of-pearl and ivory inlay, a magnificent example of the richness of carpentry at the time. The marble dikkat al-muballigh (recitation platform), supported on eight marble columns, is located in the second aisle of the qibla hall.

Madrasa of Qujmas al-Ishaqi, minaret and dome, Cairo.

Its extensive provision of over 200 rooms for students and its large library brought recognition to the mosque as a renowned academic institution in the 9th/15th century. Its academic chairs were held by the most eminent of scholars such as Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani (b.774/1372 d.853/1449) from Ascalon, (an ancient city of Palestine), an expert in interpretation of the Qur’an.

S. B.

II.1.j Madrasa of Qujmas al-Ishaqi

The madrasa of Qujmas al-Ishaqi, also known by the name of Abu Hriba, is on Darb al-Ahmar Street on the left as you leave Bab Zuwayla.

It is interesting to note that its façade appears on the Egyptian fifty pound note.

Opening times: all day except during midday and afternoon prayers (12.00 and 15.00 in winter, 13.00 and 16.00 in summer).

One of Sultan Abu Sa‘id Jaqmaq’s amirs, Qujmas al-Ishaqi, had this madrasa built. His exact date of birth is unknown, but we do however know that he was a contemporary of eight Circassian Mamluk Sultans and that he died and was buried in Damascus in 892/1486. Qujmas worked in the government palace, and went on to hold the post of khaznadar (treasurer). In the reign of Sultan Qaytbay he was named Governor of Syria.

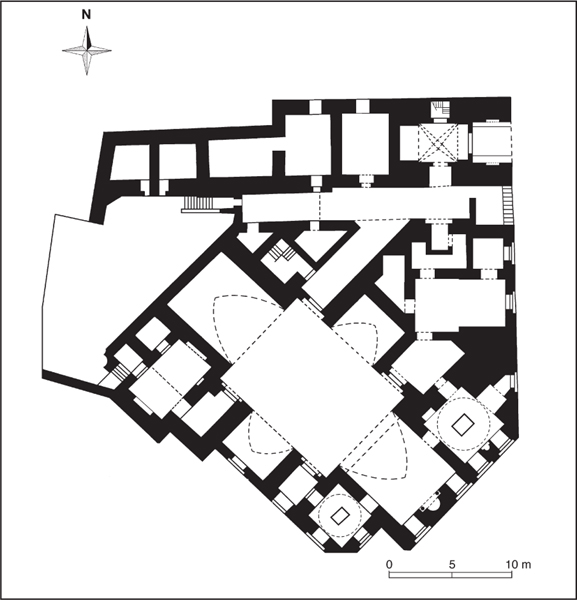

Qujmas had this tall madrasa constructed over a row of shops, the income from which paid for the building’s upkeep. Comprising a madrasa, qubba, sabil, rooms for the Sufis, a watering trough (above which there is a kuttab), a water wheel and a fountain for ritual ablutions, it is the archetypal religious complex so popular in the Circassian Mamluk era. Though the layout inside the building is similar to that of the cruciform madrasas (a durqa‘a with four iwans), in the founding documents it is clearly stated that it was designed as a congregational mosque.

With the building constructed on a triangular plot of land, the architect had to plan the rooms within the restrictions of the surrounding street layout using every inch of land available. The façade overlooks Darb al-Ahmar Street running parallel to the Fatimid City walls. It includes the north west iwan and south west qubba walls as well as two alcoves in which the entrance and the sabil were situated. The main entrance is above street level and crowned by a tri-lobed arch filled with muqarnas. Above the stone benches on either side an inscription reads: “In the name of God the Compassionate, the Merciful, mosques are for God, let none [of you] take God’s name in vane”. This Qur’anic verse clearly alludes to the role of the building as a mosque. Another inscription includes the date the madrasa was completed (886/1481).

Madrasa of Qujmas al-Ishaqi, durqa‘a ceiling, Cairo.

Madrasa of Qujmas al-Ishaqi, entrance, Cairo.

Mosque of al-Tunbugha al-Maridani, detail of entrance decoration, Cairo.

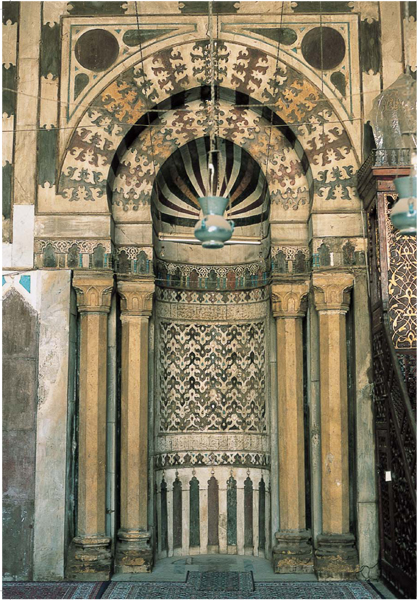

Mosque of al-Tunbugha al-Maridani, detail of mihrab decoration, Cairo.

This mosque is considered one of the most important buildings of the Qaytbay period and among the most outstanding in artistic terms. Noted in particular for its decoration; the synthesis of colours in the marble panelling, the stonework on the walls and the innovative wooden ceilings with their decorated gilt design of exquisite figures.

A. A.

II.1.k Mosque of al-Tunbugha al-Maridani

Al-Tunbugha al-Maridani Mosque is located on Darb al-Ahmar Street walking towards the Citadel.

Opening times: all day except during midday and afternoon prayers (12.00 and 15.00 in winter, 13.00 and 16.00 in summer).

Amir al-Tunbugha al-Maridani al-Saqi (cupbearer) was born around the year 719/1319. He was Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad’s son-in-law and one of his amirs and went on to govern Aleppo where he died at the age of 25.

The similarities apparent between the layout of this mosque and the mosque of al-Nasir Muhammad in the Citadel are not surprising when we learn that the same court architect, master (mu‘alim) al-Suyufi, designed them. Nevertheless, it is precisely some of the differences that are most worth pointing out. The main entrance to the mosque of al-Tunbugha al-Maridani has a plain pointed arch and in the centre of the courtyard there stands an octagonal marble font covered by a wooden dome from Sultan Hassan’s Madrasa. A dome covers the mihrab stretching across two aisles, rather than three as in the sanctuary of the Mosque of al-Nasir Muhammad. Its dimensions are similar to those rising above mihrabs in Fatimid times and to that of the Mosque of Sultan Baybars – the first of the Bahri Mamluk Sultans. Though restored in 1905, the pendentives still possess their original wooden stalactites, below which a wooden band bears gilt inscriptions of Qur’anic verses on a blue background. The decoration inside the mosque is magnificent, displaying all the finery of the most outstanding decoration of the period, from stucco and marble panels inlaid with mother of pearl, to carved wood, windows and tiles. One of the most characteristic elements of the mosque is the splendid mashrabiyya screen; separating the prayer hall from the courtyard it is one of the oldest screens still preserved in Egypt.

The minaret, too, is believed to be one of the oldest to use the bulbiform finial, a style that would later be used extensively throughout the Mamluk period.

A. A.

II.1.l Door to the House of Qaytbay in al-Razzaz (option)

The al-Razzaz House is on Bab al-Wazir Street, after Darb al-Ahmar. Cross the courtyard to see the door to the house.

Opening times: from 08.00 to sunset.

Built in the 9th/15th century, the only part that remains of Sultan Qaytbay’s house is the door, which while shorter due to its domestic purpose, maintains the traditional Mamluk-period style. It is crowned with a stalactite vault and tri-lobed arch, and has a stone bench on either side taking up the full width. The stone lintel, above which the Sultan’s emblem appears, bears a floral decoration in relief, and on the imposts a foundation text naming Sultan al-Ashraf Sha‘ban Abi al-Nasr Qaytbay.

T. T.

Mosque of al-Tunbugha al-Maridani, mashrabiyya screen separating sanctuary from courtyard, Cairo.

II.1.m Madrasa of Umm al-Sultan Sha‘ban

The Madrasa of Umm al-Sultan Sha‘ban is adjacent to the al-Razzaz house in Bab al-Wazir Street.

Opening times: Open all day except during midday and afternoon prayers (12.00 and 15.00 in winter, 13.00 and 16.00 in summer).

Al-Sultan Sha‘ban, grandson of al-Nasir Muhammad, had this madrasa built for his mother Khuwand Barka in the year 770/1369. Its layout is that of the classic cruciform madrasa with four iwans around a durqa‘a or open central courtyard. Furnished with the traditional elements (watering trough, sabil, kuttab, students’ room, prayer hall, minaret and two mausoleums), one of its most outstanding features is the way in which it is woven into the urban fabric.

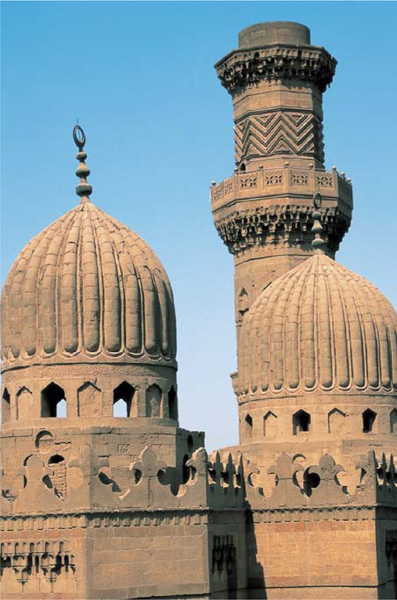

Madrasa of Umm al-Sultan Sha‘ban, minaret and domes, Cairo.

The madrasa is located on Bab al-Wazir, the main street leading to the Citadel. The minaret and main qubba are strategically placed in the far south east of the madrasa on a corner with a smaller street and thus clearly visible to the Sultan’s procession on his return to the Citadel.

Of the two entrances to the madrasa, the main one is characterised by its unusual design of Seljuq influence, characterised by the lancet arch filled with nine rows of gilt muqarnas decorated with leaf design.

To the left of this innovative entrance overlooking Bab al-Wazir Street is the sabil façade. It is formed by a wooden screen of individual panels that interlock to form geometric shapes: it is believed to be the first example of its kind.

There are two qubbas, one on either side of the qibla iwan. The southwestern qubba houses the tombs of Khuwand Barka (buried in 774/1373) and her daughter. The southeastern qubba is larger and houses the tombs of Sultan Sha‘ban (buried in 778/1377) and one of his sons. Both stone domes bear the same exterior decoration of vertical ribs dividing them into segments. The minaret, however, preserves only two of its three original sections. The lower section is octagonal with alternating blind and open pointed arches resting on double columns, with a balcony resting on rows of muqarnas. The second, while smaller, is also octagonal decorated with a horizontal chevron design.

A. A.

II.1.n Mosque of Aqsunqur (option)

The Mosque of Aqsunqur, more commonly known as the Blue Mosque, is located on the left in Bab al-Wazir Street when walking towards the Citadel.

Opening times: all day except during midday and afternoon prayers (12.00 and 15.00 in winter, 13.00 and 16.00 in summer).

Amir Aqsunqur was one of al-Nasir Muhammad’s amirs, he was also one of his sons-in-law and later became governor of Tripoli, Lebanon. Among the many buildings commissioned by Amir Aqsunqur, in this same street, we find his house, several public drinking fountains and a watering trough for animals. With his interest in architecture, he personally took charge of the supervision for the building work on the mosque. Built in 747/1347, it follows the traditional hypostyle plan; a central courtyard surrounded by four porticoes, the largest of which is the prayer hall with two aisles. Its name derives from its east wall, tiled from floor to ceiling in beautifully coloured majolica, the predominant shade being blue. This tile work is a later addition from one of the renovations carried out by the Ottoman Ibrahim Agha Mustahfazan, in 1062/1652.

Another notable feature of this mosque is its marble minbar, decorated with an unusual design of bunches of grapes and vine leaves and inlaid with coloured stones. It is one of the few minbars ever built with this costly material and one of the oldest in Cairo.

A. A.

II.1.o Palace of Alin Aq al-Husami (option)

The Palace of Alin Aq al-Husami is on Bab al-Wazir Street following on from the previous monument.

Closed due to its poor state of repair, visitors are not allowed inside.

Madrasa of Umm al-Sultan Sha‘ban, plan, Cairo.

What remains of this palace, built by Alin Aq al-Husami one of Sultan Qalawun’s amirs, tells us that it was a residential palace with two floors and one of the noblest examples of the architecture of the Bahri Mamluk era. On passing through a curved passageway the visitor reaches the ground floor which once contained storerooms, stables, a bakery, courtyard and takhtabush. The upper floor has a balcony overlooking the courtyard and small rooms covered by barrel or cross vaults.

T. T.

THE FESTIVITIES OF RAMADAN AND THE SIGHTING OF THE NEW MOON

Salah El-Bahnasi

Complex of Sultan Qalawun, dome and minaret of the madrasa, Cairo.

The beginning of the Islamic lunar calendar is designated by the official sighting of the new moon. In Mamluk times a celebratory procession was held in which the great Cadi, Cadis of the four Sunni legal rites, (shafi‘i, hanafi, hanbali and maliki), ulemas (doctors of jurisprudence) and the public took part. During the first three centuries of the Hijra, the new moon was officially sighted from the mosque of Mahmud on the slopes of Mount al-Muqattam. Later a dikka (platform) was built on its summit for those who had climbed the mountain to rest and observe the new moon. When in 478/1085, the Fatimid vizier Badr al-Din al-Ghamali built his mosque on the slopes of Mount al-Muqattam, it was from there that the new moon was officially sighted. In the Mamluk era the chosen site for the event was the minaret of the Madrasa of Sultan Qalawun in the al-Nahhasin quarter (III.1.c).

While the sighting of the new moon was of great importance for Muslims, it was more so at the beginning of the Holy month of Ramadan. The sighting was carried out with special reverence for it filled the souls of the Muslims with reverence and awe. Many historians record the procession held to celebrate the event as equal to any Sultan’s procession: streets were decorated, oil lamps lit throughout and as soon as the month of Ramadan was declared official great rejoicing took place in the streets with festivities and cannon fire.

On occasions there were discrepancies over the sighting of the new moon, and people were left confused not knowing whether to fast or to eat. One such paradoxical situation took place in the time of Sultan Barquq (r.784/1382-801/1398). The sighting of the new moon was not approved unanimously and on the following day when the Sultan was preparing to eat with his guests, news spread through Cairo that the Holy month had in fact begun. The Sultan threw his guests out, ordered the food to be taken away and declared the beginning of the fast official.

Muslims celebrate the end of the Holy month of Ramadan with the Bairam Feast or “Breaking of the Fast”, an important Islamic feast. The Sultan would go out in a solemn procession and take part in prayer. With the prayers finished, people would begin to greet each other and the Sultan and his amirs would give away gifts of clothing, presents and bags of coins to those who greeted them. Great quantities of food were prepared for the public and festivities continued in public squares and gardens with music, song and acrobats. One such activity involved walking along a tightrope stretched between the top of Bab al-Nasr and the ground, or stretched between Sultan Hassan Madrasa and the Citadel.

During Sultan al-Ghuri’s reign (906/1501-922/1516), the King of India sent two large elephants draped in red velvet that acted out a fight; the Sultan and the people were naturally overjoyed to see the show.