Health Promotion |

5 |

Pathological changes of aging may result from poor health practices acquired early in life that continue into older adulthood. The Centers for Disease Control (2004) report that, in 2000, the most common causes of death in the United States were tobacco use, poor diet, lack of physical activity, alcohol consumption, and microbial agents. Despite their advanced age, older adults may still benefit from health promotion activities, even in their later years. In fact, health promotion is as important in older adulthood as it is in childhood. Older adults are never too old to improve their nutritional level, start exercising, get a better night’s sleep, and improve their overall health and safety.

Primary prevention involves measures to prevent an illness or disease from occurring and includes

![]() Limited alcohol consumption

Limited alcohol consumption

![]() Good nutrition

Good nutrition

![]() Exercise

Exercise

![]() Adequate sleep

Adequate sleep

![]() Safe lifestyles

Safe lifestyles

![]() Updated immunizations

Updated immunizations

Secondary prevention refers to methods and procedures to detect the presence of disease in the early stages so that effective treatment and cure are more likely. Routine mammograms, hypertension screening, and prostate specific antigen blood tests are a few examples of this type of screening.

Strategies for detecting disease at an early stage involve annual physical examinations; laboratory blood tests for tumor markers, cholesterol, and other highly treatable illnesses; and diagnostic imaging for the presence of internal disease. Secondary disease-specific early detection guidelines are listed in Table 5.1.

Tertiary prevention is needed after the disease or condition has been diagnosed and treated in an attempt to return the client to an optimum level of health and wellness despite the disease or condition. Physical, occupational, and speech pathology services following a cerebrovascular accident are typical examples of tertiary prevention strategies.

![]() Misconceptions about the benefits of health promotion for older adults

Misconceptions about the benefits of health promotion for older adults

![]() Separating the normal changes of aging from pathological illness

Separating the normal changes of aging from pathological illness

![]() Motivation to change (see motivational theories in chapter 3)

Motivation to change (see motivational theories in chapter 3)

![]() Lack of reimbursement for health promotion behavior

Lack of reimbursement for health promotion behavior

Alcohol dependence and alcoholism has the potential for great consequences among older adults, including negative effects on

![]() Function

Function

![]() Cognition

Cognition

![]() Health

Health

![]() Quality of life

Quality of life

Alcohol use is difficult to assess among older adults.

![]() Symptoms of alcohol use among older adults include alteration in mental status and function, which may mimic the symptoms of delirium, dementia, or depression.

Symptoms of alcohol use among older adults include alteration in mental status and function, which may mimic the symptoms of delirium, dementia, or depression.

![]() Older adults are usually no longer in the workforce, where the daily performance failures that are common with alcohol usage are often detected.

Older adults are usually no longer in the workforce, where the daily performance failures that are common with alcohol usage are often detected.

Alcoholism is a greater problem for older adults because older adults are not able to physiologically detoxify and excrete alcohol as effectively as younger people. Assessment of alcohol use may be most effectively accomplished using an instrument such as the CAGE questionnaire.

![]() Have you ever tried to Cut down on your drinking?

Have you ever tried to Cut down on your drinking?

![]() Do you become Annoyed when others ask you about drinking?

Do you become Annoyed when others ask you about drinking?

![]() Do you ever feel Guilty about your drinking?

Do you ever feel Guilty about your drinking?

![]() Do you ever use alcohol in the morning, as an Eye-opener?

Do you ever use alcohol in the morning, as an Eye-opener?

Older adults with alcohol problems who receive treatment are capable of achieving positive health outcomes. In fact, when older adults receive effective treatment for their alcoholism, their prognosis is much better than it is for their younger counterparts. When alcohol abuse is suspected among older adults, it is necessary to refer them immediately to an appropriate program for effective treatment—such as Alcoholics Anonymous or an in- or outpatient detoxification and treatment program. Special treatment considerations should be applied to older adults during acute alcohol withdrawal related to normal and pathological aging changes.

Cigarette smoking has multiple harmful effects on older adults, including, but not limited to, cardiovascular and respiratory disease and cancer. The current cohorts of older adults are among the first people who have potentially smoked throughout their entire adult lives. It is possible for older adults to experience the benefits of smoking cessation even in old age. It is important to note that older adults may be more motivated to quit smoking than their younger counterparts because they are likely to experience some of the damage that smoking has caused. Smoking cessation interventions include

![]() Behavioral management classes

Behavioral management classes

![]() Support groups

Support groups

![]() Nicotine replacement therapies

Nicotine replacement therapies

![]() Antidepression medications (Wellbutrin™)

Antidepression medications (Wellbutrin™)

It is estimated that approximately 20% of older adult diets are inadequate. The many risk factors for nutrition among older adults include the following:

![]() Normal changes of aging place older adults at a higher risk for nutritional deficiencies

Normal changes of aging place older adults at a higher risk for nutritional deficiencies

![]() Pathological diseases

Pathological diseases

![]() Decreases in smell, vision, and taste and the high frequency of dental problems

Decreases in smell, vision, and taste and the high frequency of dental problems

![]() Lifelong eating habits, such as a diet high in fat and cholesterol

Lifelong eating habits, such as a diet high in fat and cholesterol

![]() Diminishing senses of taste and smell result in less desire to eat and may lead to malnutrition

Diminishing senses of taste and smell result in less desire to eat and may lead to malnutrition

![]() Limited income

Limited income

![]() Lack of transportation to purchase food

Lack of transportation to purchase food

![]() Social isolation

Social isolation

Failure to thrive (FTT) is a syndrome used to describe clients who experience malnutrition in the absence of an explanatory medical diagnosis. FTT is often found with

![]() Dehydration

Dehydration

![]() Impaired cognition

Impaired cognition

![]() Impaired ambulation

Impaired ambulation

![]() Difficulty with at least two activities of daily living

Difficulty with at least two activities of daily living

![]() Neglect

Neglect

Nutritional assessment might use

![]() 24-hour recall

24-hour recall

![]() Nutritional assessment forms (see Figure 5.1)

Nutritional assessment forms (see Figure 5.1)

Interventions to promote nutrition include

![]() Patient teaching and reinforcements regarding good nutrition (see chapter 3 for a discussion of the theories and principles of teaching and learning)

Patient teaching and reinforcements regarding good nutrition (see chapter 3 for a discussion of the theories and principles of teaching and learning)

![]() A suggested resource is the MyPyramid food guide (see Figure 5.2)

A suggested resource is the MyPyramid food guide (see Figure 5.2)

The role of regular exercise in promoting health and preventing disease cannot be sufficiently emphasized. Regular exercise results in

![]() Reduced constipation

Reduced constipation

![]() Improved sleep

Improved sleep

![]() Lower blood pressure

Lower blood pressure

![]() Lower cholesterol levels

Lower cholesterol levels

![]() Improved digestion

Improved digestion

![]() Weight loss

Weight loss

![]() Enhanced opportunities for socialization

Enhanced opportunities for socialization

![]() Improved pain control

Improved pain control

![]() Increased temperature control in response to environmental changes

Increased temperature control in response to environmental changes

![]() Reduced risk of hypothermia

Reduced risk of hypothermia

Despite the many benefits of exercise among older adults, the amount of exercise generally decreases as one ages.

Interventions to promote exercise include helping older adults to choose an exercise program that they enjoy and in which they are motivated to participate. Sample exercise programs include

![]() Walking

Walking

![]() Aquacise

Aquacise

![]() Strength training

Strength training

![]() Yoga

Yoga

The inability to fall asleep and to sleep through the night are among the most frequent complaints of older adults. Many older adults report difficulty falling asleep and frequent night-time awakenings. About half of older adults report one or more sleep problems. Key indicators of sleep disorders include

Note. The Mini Nutritional Assessment and MNA have been developed by and are trademarks owned by Société de Produtis Nestlé. © Nestlé, 1994, Revision 2006. N67200 12/99 10M

Sources: Overview of the MNA®: Its History and Challenges, by B. Vellas, H. Villars, G. Abellan, et al., 2006, Journal of Nutritional Health and Aging, 10, pp. 456–465. Screening for Undernutrition in Geriatric Practice: Developing the Short-Form Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA-SF), by L. Z. Rubenstein, J. O. Harker, A. Salva, Y. Guigoz, & B. Vellas, 2001, Journal of Gerontology, 56A, pp. M366–M377. The Mini-Nutritional Assessment (MNA®) Review of the Literature: What Does It Tell Us?, by Y. Guigoz, 2006, Journal of Nutritional Health and Aging, 10, pp. 466–487. For more information: http://www.mna-elderly.com

Note. From U.S. Department of Agriculture, Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion, CNPP=15. (2005, April). Retrieved April 15, 2008, from http://www.MyPyramid.gov

![]() Prolonged periods of difficulty falling asleep or getting back to sleep after night-time awakenings

Prolonged periods of difficulty falling asleep or getting back to sleep after night-time awakenings

![]() Daytime fatigue or sleepiness

Daytime fatigue or sleepiness

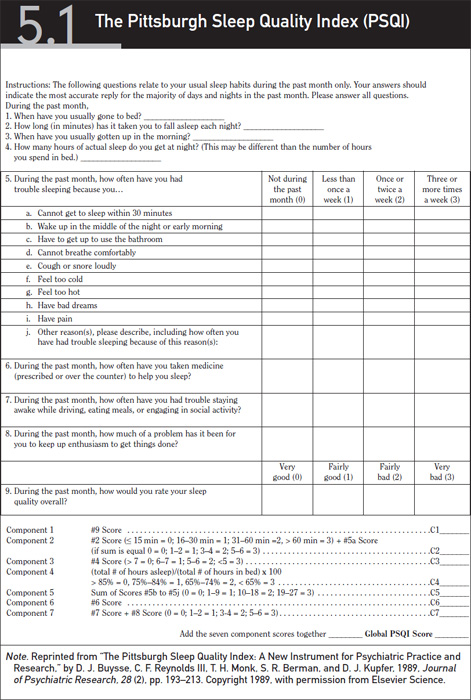

Sleep patterns are affected by both normal and pathological aging changes. Sleep assessment is the first key to successful sleep management (see Exhibit 5.1). Sleep interventions include the following:

![]() Increase physical activity during the day.

Increase physical activity during the day.

![]() Increase pain medication or alternative pain methods to help older adults suffering from painful conditions to get better rest at night.

Increase pain medication or alternative pain methods to help older adults suffering from painful conditions to get better rest at night.

![]() Examine the sleep environment. Adjustments in noise and lighting may help older adults to sleep better.

Examine the sleep environment. Adjustments in noise and lighting may help older adults to sleep better.

![]() Assess the stress in the lives of older adults. Identification and resolution of stressful life factors may help older adults to sleep more peacefully.

Assess the stress in the lives of older adults. Identification and resolution of stressful life factors may help older adults to sleep more peacefully.

![]() Daytime napping tends to interfere with a good night’s sleep. Older adults who choose to nap during the day should acknowledge that the napping will likely reduce the total nighttime sleep needed.

Daytime napping tends to interfere with a good night’s sleep. Older adults who choose to nap during the day should acknowledge that the napping will likely reduce the total nighttime sleep needed.

One of the greatest advances in primary prevention and public health has been the use of immunizations to prevent disease. Adult immunization guidelines are given in Figure 5.3. Two vaccine-preventable diseases that occur commonly in the elderly with great risk for morbidity and mortality are influenza and viral pneumonia. Influenza results in approximately 42.7 million hospitalizations and deaths annually. Despite this high number and the availability of a preventable vaccine, less than 60% of community-dwelling older adults get vaccinated each year.

A major Healthy People 2010 objective is to increase influenza vaccination among all older adults, especially those with:

![]() Respiratory disorders

Respiratory disorders

![]() Chronic heart diseases

Chronic heart diseases

![]() Chronic renal disease

Chronic renal disease

![]() Immunosuppression

Immunosuppression

Vaccination is contraindicated in people who are allergic to eggs and in those who have experienced a reaction to the vaccine in the past. Pneumonia is an infectious disease caused by several possible organisms.

![]() Pneumonia is the leading cause of death from infectious disease in the United States.

Pneumonia is the leading cause of death from infectious disease in the United States.

![]() It is the sixth leading cause of death overall.

It is the sixth leading cause of death overall.

*Covered by the Vaccine Injury Compensation Program. For information on how to file a claim call 800-338-2382. Please also visit www.hrsa.gov/osp/vicp To file a claim for vaccine injury contact: U.S. Court of Federal Claims, 717 Madison Place, N.W., Washington D.C. 20005, 202-2199657

This schedule indicates the recommended age groups for routine administration of currently licensed vaccines for persons 19 years of age and older. Licensed combination vaccines may be used whenever any components of the combination are indicated and the vaccine’s other components are not contraindicated. Providers should consult the manufacturers’ package inserts for detailed recommendations.

Report all clinically significant post-vaccination reactions to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS). Reporting forms and instructions on filing a VAERS report are available by calling 800-822-7967 or from the VAERS website at http://vaers.hhs.gov/.

For additional information about the vaccines listed above and contraindications for immunization, visit the National Immunization Program Website at www.cdc.gov/nip or call the National Immunization Hotline at 800-232-2522 (English) or 800-232-0233 (Spanish).

Approved by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), and accepted by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP)

See Special Notes for Medical Conditions below—also see Footnotes for Recommended Adult Immunization Schedule, by Age Group and Medical Conditions, United States, 2003–2004 on back cover

![]()

Special Notes for Medical Conditions

A. For women without chronic diseases/conditions, vaccinate if pregnancy will be at 2nd or 3rd trimester during influenza season. For women with chronic diseases/conditions, vaccinate at any time during pregnancy.

B. Although chronic liver disease and alcoholism are not indicator conditions for influenza vaccination, give 1 dose annually if the patient is age 50 years or older, has other indications for influenza vaccine, or if the patient requests vaccination.

C. Asthma is an indicator condition for influenza but not for pneumococcal vaccination.

D. For all persons with chronic liver disease.

E. For persons < 65 years, revaccinate once after 5 years or more have elapsed since initial vaccination.

F. Persons with impaired humoral immunity but intact cellular immunity may be vaccinated. MMWR 1999; 48 (RR-06):1-5

G. Hemodialysis patients: Use special formulation of vaccine (40 ug/mL) or two 1.0 mL 20 ug doses given at one site. Vaccinate early in the course of renal disease. Assess antibody titers to hep B surface antigen (anti-HBs) levels annually. Administer additional doses if anti-HBs levels decline to <10 milliinternational units (mlU)/mL.

H. There are no data specifically on risk of severe or complicated influenza infections among persons with asplenia. However, influenza is a risk factor for secondary bacterial infections that may cause severe disease in asplenics.

I. Administer meningococcal vaccine and consider Hib vaccine.

J. Elective splenectomy: vaccinate at least 2 weeks before surgery.

K. Vaccinate as close to diagnosis as possible when CD4 cell counts are highest.

L. Withhold MMR or other measles containing vaccines from HIV-infected persons with evidence of severe immunosuppression. MMWR 1998; 47 (RR-8):21–22; MMWR 2002; 51 (RR-02):22–24.

![]() Estimates indicate that pneumococcal infections are responsible for approximately 100,000 deaths per year.

Estimates indicate that pneumococcal infections are responsible for approximately 100,000 deaths per year.

![]() Pneumonia vaccination is recommended every 10 years or more frequently in high-risk populations.

Pneumonia vaccination is recommended every 10 years or more frequently in high-risk populations.

![]() Many older adults are unvaccinated against pneumonia.

Many older adults are unvaccinated against pneumonia.

![]() Pneumonia vaccine is effective at preventing 56% to 81% of viral infections.

Pneumonia vaccine is effective at preventing 56% to 81% of viral infections.

![]() Pneumonia vaccine is estimated to prevent 80% of pneumonia-related deaths.

Pneumonia vaccine is estimated to prevent 80% of pneumonia-related deaths.

![]() The vaccine is not useful in some immunocompromised patients.

The vaccine is not useful in some immunocompromised patients.

![]() Indications for the pneumonia vaccine:

Indications for the pneumonia vaccine:

![]() Everyone older than 65 years

Everyone older than 65 years

![]() People ages 2 to 64 who have chronic illness or live in high-risk areas

People ages 2 to 64 who have chronic illness or live in high-risk areas

![]() Older adults with chronic lung, heart, kidney, sickle cell disease, or diabetes

Older adults with chronic lung, heart, kidney, sickle cell disease, or diabetes

The use of herbal medications to treat commonly occurring normal and pathological changes of aging has grown considerably over the past decade. The Gerontological Society of America (2004) reports that one-third of older adults used alternative medicine in 2002.

Herbal medications may be preferred over traditional medication among many cultural groups including Chinese and other Asian cultures. The availability of these herbals, often referred to as nutraceuticals, and the anecdotal evidence of their effectiveness have spawned the sudden growth in sales of these supplements. Nutraceuticals also tend to be less expensive than prescription drugs.

The Gerontological Society of America (2004) reports that their perceived effectiveness and lower cost led to 13% of older adults turning to herbal medications over prescriptions to treat medical problems.

Herbal supplements commonly used by older adults:

![]() Vitamins C, D, and E, which have shown some evidence of reducing symptoms of osteoarthritis. However, vitamin E has been shown to result in increased risk of bleeding disorders.

Vitamins C, D, and E, which have shown some evidence of reducing symptoms of osteoarthritis. However, vitamin E has been shown to result in increased risk of bleeding disorders.

![]() Ginger and glucosamine have also been used extensively by older adults to reduce arthritis-related pain. However, glucosamine may interfere with insulin and oral hypoglycemic medications in diabetic patients.

Ginger and glucosamine have also been used extensively by older adults to reduce arthritis-related pain. However, glucosamine may interfere with insulin and oral hypoglycemic medications in diabetic patients.

![]() Black licorice has been thought to reduce joint inflammation to reduce symptoms of arthritis but may cause irregular heart rhythms and may interact with some diuretics and vitamin K.

Black licorice has been thought to reduce joint inflammation to reduce symptoms of arthritis but may cause irregular heart rhythms and may interact with some diuretics and vitamin K.

![]() Gingko biloba is widely used by older adults to enhance memory, but it has been shown to increase the risk of bleeding disorders.

Gingko biloba is widely used by older adults to enhance memory, but it has been shown to increase the risk of bleeding disorders.

![]() Saw palmetto is used by many older men to reduce symptoms of enlarged prostate glands and to prevent prostate cancer. However, this nutraceutical may falsely lower prostate specific antigen levels and has been shown to result in increased risk of bleeding disorders.

Saw palmetto is used by many older men to reduce symptoms of enlarged prostate glands and to prevent prostate cancer. However, this nutraceutical may falsely lower prostate specific antigen levels and has been shown to result in increased risk of bleeding disorders.

![]() Ginseng is used by older adults to reduce stress.

Ginseng is used by older adults to reduce stress.

![]() St. John’s wort is often used as an alternative or adjunct treatment for depression.

St. John’s wort is often used as an alternative or adjunct treatment for depression.

![]() Cascara sagrada may result in hypokalemia.

Cascara sagrada may result in hypokalemia.

A summary of commonly used herbal medications and their indications is provided in Table 5.2.

Herbal Components Under Study by the National Toxicology Program |

Aloe vera gel |

Widely used herb, both as a dietary supplement and component of cosmetics. Ninth highest in sales in the United States (2002). The gel has been used for centuries as a treatment for minor burns and is increasingly being used in products for internal consumption. |

Black cohosh |

Used to treat symptoms of premenstrual syndrome, dysmenorrhea, and menopause. Ranked 11th in sales in 2002. |

Bladderwrack |

A source of iodide used in treatment of thyroid diseases and also used as a component of weight-loss preparations. |

Comfrey |

Herb consumed in teas and as fresh leaves for salads; however, it contains pyrrolizidine alkaloids (e.g., symphatine), which are known to be toxic. Used externally as an anti-inflammatory agent in the treatment of bruises, sprains, and other external wounds. Based in part on NTP studies on the alkaloid components of comfrey, the FDA has recommended that manufacturers of dietary supplements containing this herb remove them from the market. |

Echinacea purpurea extract |

The most commonly used medicinal herb in the United States (2002). Used as an immunostimulant to treat colds, sore throat, and flu. |

Ephedra |

Also known as Ma Huang; 21st in sales in 2002. Traditionally used as a treatment for symptoms of asthma and upper respiratory infections. Often found in weight loss and “energy” preparations, which usually also contain caffeine. Use has been associated with side effects such as heart palpitations, psychiatric and upper gastrointestinal effects, and symptoms of autonomic hyperactivity such as tremor and insomnia, especially when taken with other stimulants. |

Ginkgo biloba extract |

Fourth highest in sales (2002). Ginkgo fruit and seeds have been used medicinally for thousands of years. The extract of green-picked leaves has shown increasing popularity in the United States. Ginkgo biloba extract promotes vasodilatation and improved blood flow and appears beneficial, particularly for short-term memory loss, headache, and depression. |

Ginseng and ginsenosides |

Ginseng ranked 13th in sales of medicinal herbs in 2002 down from 4th in 1996. Ginsenosides are thought to be the active ingredients. Ginseng has been used as a treatment for a variety of conditions including hypertension, diabetes, and depression, and been associated with various adverse health effects. |

Goldenseal |

Seventeenth in sales (2002). Traditionally used to treat wounds, digestive problems, and infections. Current uses include as a laxative, tonic, and diuretic. Mistakenly thought to disguise the presence of other drugs in drug tests. |

Green tea extract |

Used for its antioxidative properties, 15th in sales in 2002. |

Kava kava |

The 25th most widely used medicinal herb (2002), kava kava has psychoactive properties and is sold as a calmative and antidepressant. A recent report of severe liver toxicity has led to restrictions of its sale in Europe and has apparently affected sales in the United States. Some components may alter efficacy/toxicity of therapeutic agents. |

Milk thistle extract |

Ranked eighth in sales in 2002. Used to treat depression and several liver conditions including cirrhosis and hepatitis and to increase breast milk production. |

Pulegone |

A major terpenoid constituent of the herb, Pennyroyal, is found in lesser concentrations in other mints. Pennyroyal has been used as a carminative insect repellent, emmenagogue, and abortifacient. Pulegone has well-recognized toxicity to the liver, kidney, and central nervous system. |

Senna |

Laxative with increased use due to the removal of one of the widely used chemical-stimulant type laxatives from the market. Study in p53+/– transgenic mice is in progress. |

Thujone |

Terpenoid found in a variety of herbs, including sage and tansy, and in high concentrations in wormwood. Suspected as the causative toxic agent associated with drinking absinthe, a liqueur flavored with wormwood extract. |

Note. From National Toxicology Program. Medicinal herbs. Retrieved March 23, 2008, from http://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/files/herbalfacts06.pdf |

|

Buysse, D. J., Reynolds III, C. F., Monk, T. H., Berman, S. R., & Kupfer, D. J. (1989). The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 28(2), 193–213.

Centers for Disease Control and Merck Institute for Aging and Health. (2004). The state of aging and health in America. Retrieved July 13, 2007, from http://www.cdc.gov/aging/pdf/State_of_Aging_and_Health_in_America_2004.pdf

Gerontological Society of America. (2004, July). Alternative medicine gains popularity. Gerontology News, 4, 3.

Guigoz, Y. (2006). The mini-nutritional assessment (MNA®) review of the literature: What does it tell us? Journal of Nutritional Health and Aging, 10, 466–487.

Lichtenstein, A. H., Rasmussen, H., Yu, W. W., Epstein, S. R., & Russell, R. M. (2008). Modified MyPyramid for older adults. Journal of Nutrition Commentary, 5–11.

National Toxicology Program. (2008). Medicinal herbs. Retrieved March 23, 2008, from http://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/files/herbalfacts06.pdf

Rubenstein, L. Z., Harker, J. O., Salva, A., Guigoz, Y., & Vellas, B. (2001). Screening for undernutrition in geriatric practice: Developing the short-form mini nutritional assessment (MNA-SF). Journal of Gerontology, 56A, M366–M377.

Vellas, B., Villars, H., Abellan, G., et al. (2006). Overview of the MNA®: Its history and challenges. Journal of Nutritional Health and Aging, 10, 456–465.