CHAPTER 10

Reconstructing Market Boundaries—Systematically

HOW CAN YOU RECONSTRUCT market boundaries and change the conversations you have about where opportunities reside so as to conceive and open up a new value-cost frontier? Every organization, even the most innovative, must face this question sooner or later. If you have embarked on a blue ocean shift initiative, it is the question your team is now primed to take on.

Through their work together, team members have come to have a visceral understanding of how the blue ocean shift process and tools enable them to see what they haven’t seen before, to build their collective confidence, and to develop a new level of awareness and openness. People feel how their participation in the process is increasing their personal understanding of the market and, with it, their commitment to the process. They are likely clear about the red ocean the industry is immersed in and the need to shift out of it. They have seen how a focus on benchmarking and beating the competition has not only blinded the industry’s players to a wealth of unexplored opportunity spaces, but also created pain points that limit its size. They have identified the contours of new demand that could potentially be unlocked by thinking differently and offering noncustomers, as well as current buyers, a leap in value. Now they are ready for the process to shift, from broadening perspectives and imagining what could be, to generating practical, real-world, blue ocean options.

To this end, we developed the six paths framework to demystify and structure the work of seeing opportunities where others see only red oceans of competition. This stage of the process is where team members dive head-on into the market, get their hands dirty, and do the kind of grounded, field-based research that can generate actionable insights for changing the strategic playing field. Simply getting out into the field, however, is not enough. If you want different answers, you need to ask different questions and listen to different people. People are as insightful (or not) as the questions you ask them. Ask standard questions and you’ll get standard responses that keep you anchored in the red ocean. Ask questions that force people to think in fresh and innovative ways, and you’ll gain insights into new market creation. As you will see, each of the six paths guides you to look at the market universe in a new way by shifting the questions you ask and the people you listen to.

Imagine a one-way street you’ve gone down a thousand times in your car and you think you know by heart. Then one day you walk up that very same street but in the reverse direction. Suddenly you’re jolted. You notice a house that you never observed before, or a tall tree in someone’s yard you’d never taken notice of, or a stunning view of a distant lake that was hidden from your sight when you traveled in the old one-way direction. That’s what the six paths do. They show you how to travel down roads in new ways so you see new things that were always there but had been blocked from your view. And just as it’s awe-inspiring in life when we see new things we hadn’t seen before that had been in front of us all along, people feel enlightened in the process when they, with the help of the six paths, learn to see the same reality differently and discover blue ocean opportunities.

How was this analytic tool developed? When we analyzed strategic moves that created commercially compelling blue oceans by reconstructing market boundaries, we found the six systematic patterns depicted in this framework repeated across multiple industries. Does this mean there aren’t other ways to create new market space? Of course not. However, in our role as advisors, working side by side with organizations across diverse industry sectors, we have seen firsthand how effective this framework can be.

The Six Paths Framework: How It Works to Open Up a New Value-Cost Frontier

Most organizations follow a similar pattern in developing their strategies: They start by analyzing their industry: Have new competitors entered? Is demand flat, rising, or declining? Have raw materials prices gone up? Next, they focus on the players in their particular strategic group: the companies or organizations in the industry that pursue a similar strategy or approach to the market. Luxury hotels will tend to assess what other luxury hotels are up to, for example, while budget hotels will do the same versus their strategic competitors. But since they operate in different strategic groups, neither one tends to pay much attention to the other. Then, the strategic lens narrows once again, to focus on current customers—their own and those of their competitors—and how the distinctive needs of those customers can best be served. Not surprisingly, therefore, budget hotels don’t pay much heed to the wealthy, nor do luxury hotels focus on lower-and middle-income individuals. Both sets of hotels will concentrate on making the best hotel they can, however. In other words, they will define the scope of their offering as the industry has long defined it. With this will go a focus on features that align with their strategic group’s customary orientation. For budget hotels, this will mean providing functional, low-priced rooms, while luxury hotels will prioritize sophistication and refinement to enhance their image and prestige. Finally, they will consider the impact of external forces, such as environmental or safety concerns, which are affecting the industry and to which they have to adapt.

In sum, executives tend to define their strategic playing field—and limit their opportunity horizon—on the basis of six conventional boundaries: industry, strategic group, buyer group, scope of the product or service offering, nature of the offering’s appeal, and time. Nonprofit leaders, government decision makers, entrepreneurs, and even one-off Main Street storeowners and professional firms typically do the same.

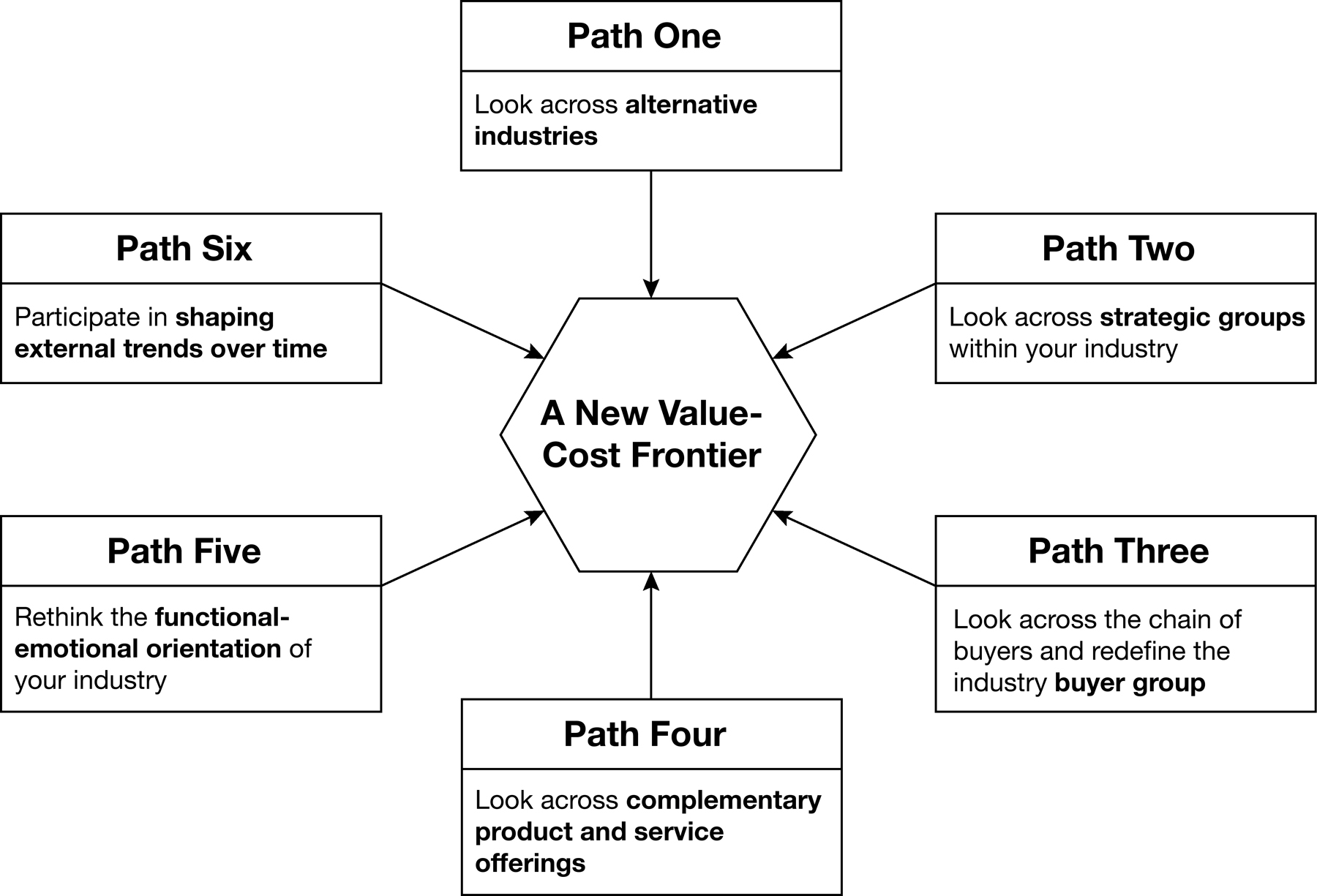

Yet boundaries do not define what must be or should be. They merely define what is. None of them is a law of nature. All of them are the product of people’s minds, and, as such, they are open to change. But over time this fact tends to be forgotten, and people come to take them as eternal truths. They become a conceptual cage that organizations lock themselves into, even though every one of these boundaries was created by an individual organization. And just as people and individual organizations created them, so they can change them if they are prepared to think in a different way. The six paths framework, shown in figure 10-1, provides six systematic ways to shift the lens you use in looking at the market universe and open up a new value-cost frontier. Path by path, the framework explains how to uncover plausible blue ocean opportunities by looking across an industry’s self-imposed boundaries, instead of remaining stuck within them. It also incorporates seasoned advice on what to look and listen for as you pursue each path. Let’s explore the six paths in turn.

The Six Paths to Open Up a New Value-Cost Frontier

Path One: Look Across Alternative Industries

| Red Ocean Lens: | Blue Ocean Lens: | |

| Focus on rivals in your industry |  |

Look across alternative industries |

Organizations compete within their own industry and with industries that offer alternative products or services. In making their decisions, buyers often weigh alternative industries and make trade-offs, explicitly or implicitly: Want to put your best foot forward with neat, wrinkle-free shirts—do you iron them at home, send them to the dry cleaner, or only buy shirts made with wrinkle-free material? Going from New York to Washington, D.C., do you take a plane, a train, drive your car, or take a bus? This thought process is intuitive for consumers. Yet, the tight strategic lens that most organizations use drives them to focus on beating rivals within their existing industry, keeping them trapped in the red ocean. To open up a new value-cost frontier, you have to look across alternative industries and understand why buyers choose one over the other.

The objective in this path is to identify the problems or needs your offering currently solves, and then to generate a list of other solutions or industries noncustomers use to address the same problems or satisfy the same needs. Remember that the focus is not on alternatives within your industry—why people choose to fly on one airline over another, for example—but on alternative industries that serve the same function or solve the same problem, but that have a different form. What are the decisive sources of value and the detractors of value that make people gravitate to and choose one alternative over another?

Although there may be several alternative industries to the industry you’re in or targeting, you should focus on the one(s) that has (have) the largest catchment(s) of demand. These noncustomers hold the key to the greatest number of potential new buyers, and they are the ones you want to interview.

Having identified the relevant alternatives, you need to ask people why they choose one over the other. This question shifts the discussion from all the factors an industry competes on—factors that buyers have been trained to expect and organizations love to marginally improve on, typically for little overall gain—to the factors that decisively create or detract from value. By probing in this way, buyers reveal not the branches of an industry but the fundamental trunk or basic utility that justifies the industry’s very existence and size.

What most teams quickly discover is that, despite the wide set of factors alternative industries compete on, one or two usually determine whether people patronize them. For example, why do people hire electricians instead of going to a hardware store to do it themselves, or vice versa? More than anything else, two factors drive people to hire an electrician—expertise and having no time to do it themselves. And only one factor drives most people to patronize a hardware store—cost. The aim here is to drill down to the factors that cause buyers to choose other industry offerings than yours, find a way to combine these decisive factors, and then reduce or eliminate everything else, thereby unlocking new market space that will be commercially viable because it focuses on precisely what potential buyers value.

Remember, asking people why they trade across industries is not the same as asking what makes an alternative industry different, which can reveal a whole host of factors that may indeed be “clever” or different, but that also may have very little value. To avoid getting distracted by “clever ideas,” stay focused on why people choose for and against your industry or the alternative. Their answers will signal the decisive value factors to create and eliminate in order to develop a blue ocean offering that is both differentiated and low cost. Exhibit 10-1 outlines the action steps of path one.

Path Two: Look Across Strategic Groups Within Your Industry

| Red Ocean Lens: | Blue Ocean Lens: | |

| Focus on your competitive position within a strategic group |  |

Look across strategic groups within your industry or target industry |

Most companies focus on outcompeting their rivals to improve their position within their strategic group or market segment. In the hotel industry, for example, five-star hotels tend to focus on outdoing other five-star hotels, three-star hotels focus on outcompeting other three-star hotels, and so on. But this only keeps them doggy-paddling in a red ocean. The key to a blue ocean shift is to understand what factors determine buyers’ decision to trade up or down from one strategic group to another. This allows you to distinguish between the range of factors on which strategic groups compete, and the decisive few that drive buyers’ decisions to choose one over the other. Again, the focus here is not on why buyers choose one particular organization over another, but on why they trade up or down across strategic groups. This will allow you to understand the trade-offs the customers of a strategic group are making when they choose across strategic groups. Understanding the factors that are decisive for noncustomers as well as customers lets you emphasize those factors while eliminating and reducing everything else.

Take the health management industry, a B2B industry that provides large corporations and insurance companies with health management services for employees’ health. HealthMedia, a player in the industry, was on the brink of collapse in this red ocean. After being forced to take 85 employees down to 18 to stabilize the company, in 2006 its new CEO, Ted Dacko, set the goal to grow it from US$5 million in revenues to US$100 million in four years by using the blue ocean approach. At the time the industry had two strategic groups—one offering telephonic counseling, predominantly for severe medical conditions like disease management; the other offering generic digitalized content, like WebMD.

As HealthMedia explored why buyers traded across these strategic groups, it found that, despite all the factors players competed on, buyers traded up to telephonic counseling for one overriding reason—high efficacy—while they traded down to digitalized content for low cost. In essence, companies competing in telephonic counseling were following a classic differentiation strategy, offering high efficacy through specialized counseling mainly for severe health challenges, but at a high cost. By contrast, those competing in digitalized content followed a classic low-cost strategy of offering generic health information at a low price but with low efficacy. These trade-offs limited employees’ use of both strategic groups’ offerings, creating an ocean of noncustomers.

The focus of telephonic counseling on severe health challenges meant that most employees’ use for it is limited, since what the majority of employees primarily need coaching in is their chronic health issues, like high blood pressure, high cholesterol, stress, depression, insomnia, binge eating, and the like. Besides, its high cost meant that companies could not afford to offer it widely. Regarding generic digitalized content, due to its low efficacy, it did not inspire high employee participation, either.

Instead of competing in either strategic group, HealthMedia set out to break these trade-offs. The result was opening up a new value-cost frontier in the industry by creating a new market space called digital health coaching, which combined the far lower cost of digitalized content with a leap in efficacy through interactive online questionnaires that digitally matched people’s self-reported challenges with a health plan that would work best for them. And the best part was that HealthMedia offered digital health coaching for the most prevalent health challenges people face, so the offering was relevant to nearly all employees. The result was a leap in value for companies who could now offer digitalized health coaching to a broad swath of employees with high efficacy at a low price. Within just two years, HealthMedia’s blue ocean was so compelling that Johnson & Johnson swooped in and purchased the company for US$185 million, an amount far higher than its already ambitious four-year revenue goal of US$100 million.

For your analysis of this path, choose the largest two strategic groups to explore. Typically, we recommend that you zoom in on the one that captures the largest share of customers, and the one that has the largest share of profitable growth, if they are different. If there is a small but very fast-growing strategic group, you should zoom in on that one as well.

As organizations start exploring this path, one of the most common and startling realizations is how many strategic groups have emerged in their industry in recent years, and how much the key players have tended to focus on the old guard that once monopolized their industry. Whatever the industry—from TV (reality programs, new producers from Netflix, to Amazon), to publishing (self-publishing, traditional publishing houses, e-books), the music industry (traditional labels, YouTube self-made stars, young kids rerecording), and the auto industry (Tesla, electric cars, self-driving cars), consumers’ options are exploding. Hence, just laying out the strategic groups within their industry wakes people up and lifts the scales from their eyes. Value gained already.

This path tends to be relatively easy for people to get their heads around and apply. Organizations that are big on segmentation, however, often have a tougher time distinguishing the forest from the trees. They tend to list a plethora of groups based on tiny differences in competitive offerings. They frequently fall into the segmentation trap. Should this situation arise, you need to push the team to take a step back and look for strategic commonalities that could enable them to cluster the long list of groups they’ve identified. In the case of the health management industry, for example, some telephonic counseling companies focused on wellness, others on behavioral health, and still many others on disease management. However, by stepping back HealthMedia saw that, at their core, all these players shared three overriding strategic commonalities—a focus on telephonic counseling, addressing severe—not chronic—health conditions, at a high cost. By understanding the defining contours that united these players that focused on different market segments, HealthMedia did not get distracted by segmentation differences. The point of this path, like all the others, is not to get lost in minutiae, but to identify the decisive value and cost contours that separate distinct strategic groups, as HealthMedia did. Exhibit 10-2 outlines the action steps of path two.

Exhibit 10-2

Path Three: Look Across the Chain of Buyers

| Red Ocean Lens: | Blue Ocean Lens: | |

| Focus on better serving the existing buyer group of the industry |  |

Look across the chain of buyers and redefine the industry buyer group |

Most industries converge around a common definition of their target customer. In reality, however, the purchasing decision usually involves, directly or indirectly, a chain of buyers: the users of the product or service; the purchasers who pay for it; and, in some cases, the influencers whose opinions can make the difference in a decision to purchase—or not. So for preteen girls’ clothing, the purchaser or payer is typically a parent, the users are the teens themselves, and the key influence group might be pop stars.

In thinking about who’s in the chain of buyers, it’s also worth considering potential influencers, people who could be brought into the decision-making process but currently aren’t. Retailers are a good example of an often “untargeted” buyer group for complicated purchase decisions. Just think about buying computer or stereo equipment, or wine or major household furniture—decisions that make most of us nervous. Many, if not most, of the companies that sell products in these categories spend most of their effort focused on each other and the ultimate user, the purchaser. But they have largely ignored thinking creatively about the retailers who sell their products. One of the results is relatively indifferent retail staff who could easily persuade many, if not most, people to go in one direction or another, but instead offer ho-hum knowledge, little passion, and no distinctive services to buyers of one manufacturer’s product over another. What if, instead, you offered a leap in innovative value to retailers’ staff that made them advocates for your products and services? Would your products start flying out the door?

While the three groups of buyers may overlap, they are often distinct, as are their value preferences. Remember the school lunch provider we listened in on in chapter 7? The purchaser’s primary objective was getting the best terms and prices, whereas having the best-tasting lunch was what the users, the students, valued most. Shifting the focus from better serving the industry’s traditional buyer group to other groups the industry has historically ignored can be the key to uncovering hidden sources of utility and opening up new market space.

Think of the commercial fluorescent lighting you see in major retailers, supermarket chains, and corporate offices. When Philips Electronics set out to create a blue ocean, it shifted its focus from the industry’s red ocean target—corporate purchasers—to a key influence group, chief financial officers (CFOs). In speaking with CFOs, Philips learned that the price of fluorescent lighting that corporate purchasers focused on was a small fraction of the total cost. An even larger component was the cost of disposal because of the high mercury content in fluorescent bulbs. Corporate purchasers never saw that cost, but CFOs did. This gave Philips the insight to create an environmentally friendly fluorescent bulb that could eliminate 100 percent of corporate disposal costs, because it could be thrown in the garbage, instead of having to be carted off to a special dump site. Philips then made the case for buying the new bulbs, which had a higher price and margin but a lower total cost overall, to the CFOs who wielded their power to influence the purchase decision in favor of Philips’s environmentally friendly bulbs.

When interviewing people in the “untargeted” buyer groups, conduct the interviews in each interviewee’s natural setting. If retailers are an untargeted buyer group, for example, conduct the interviews on the retail floor to get a sense of the store, the layout challenges, the retail staff’s issues, the way customers wander around and talk to sales staff, and the speed of checkout. This gives you the benefit of seeing what the retailers themselves may not be able to articulate or even realize. Oftentimes, an outsider observing with fresh eyes sees the challenges, opportunities, and potential solutions far better than the players themselves. Exhibit 10-3 outlines the action steps of path three.

Exhibit 10-3

Path Four: Look Across Complementary Product and Service Offerings

| Red Ocean Lens: | Blue Ocean Lens: | |

| Focus on maximizing the value of the product or service offering as defined by your industry |  |

Look across the total solution buyers seek to understand the complementary products and services that enhance or detract from your offering’s value |

Few products or services are used in a vacuum; in most cases, other products or services affect their value. But in most industries, rivals converge within the conventional boundaries of their industry’s product or service offering and focus their efforts solely on maximizing its value. The key to value innovation is to define the total solution buyers seek when they choose a product or service, and then to eliminate the pain points and points of intimidation across the total solution. A simple way to do this is to think about what happens before, during, and after your product and service is used.

By broadening your understanding of the total solution buyers need or seek, you can often discover new sources of trapped value. Take the electric kettle industry in the UK. Although the electric kettle is central to the British public’s love of afternoon tea, the industry had become a veritable red ocean with low profit margins and little growth. While the industry had long competed on price and aesthetic design, Philips Electronics shifted its focus to understanding the total buyer experience. In the process, Philips discovered that the central challenge British tea drinkers faced had nothing to do with the kettle itself; it was the lime scale in municipal water. Before the tea drinkers could enjoy their freshly brewed tea, they often had to fish out the lime scale floating in it with a spoon. Kettle companies never thought to address the problem because it had nothing to do with their industry’s offering. But by looking across the buyer’s experience and thinking about the whole range of complementary products and services buyers needed, Philips saw this block to utility and created a teakettle with a changeable filter that removed the scale when the tea was poured. The result: Philips’s teakettle turned a slow-growth industry into a fast-growth one, lifted its price point, and created a new repeat revenue stream in changeable filters.

As this example indicates, it is critical to visit users to see firsthand what happens before, during, and after the use of your product or service. Why? Because only then can you experience the full context and see the range of unvoiced steps and challenges. When people were asked what they did with their electric teakettles, the answer was: Plug it in, turn it on, boil water, pour, and drink. But when Philips visited people’s homes and watched how people used their teakettles, the lime scale problem quickly jumped out. From the users’ point of view, lime scale had nothing to do with the kettle, so they never thought to voice the problem. Others had become so accustomed to fishing for lime scale that they didn’t even consciously register doing it. Lesson: When you ask people about an offering, they tend to focus on the offering and, as a result, their answers rarely stray far from what the industry currently does.

In visiting users, the point is not to sit in their homes, offices, or factories and batter them with questions. It is to observe them actually using the product or service, so the unvoiced, taken-for-granted assumptions they make and the steps they take can be revealed. Here you want to watch for the processes or circumstances that trigger the need or desire to use the product or service. Are there inconveniences? Are the triggers too costly or intimidating, curbing demand for your product or service? What happens before your customers use your product? What happens during (or around) its use? And what happens afterward?

The buyer utility map, explored in chapter 8, provides a helpful tool for thinking about these observations, because it provides a structure that ensures that you, yourself, don’t remain trapped within the narrow confines of your industry. Learning how to observe insightfully and see unvoiced, trapped value is a nonobvious skill for many. But by thinking in terms of the six utility levers and the six stages of the buyers’ experience cycle, you are primed to observe more broadly and insightfully. The primary objective is to uncover all the blocks to utility, even if those blocks are not related to your industry as it currently defines itself—be it lime scale for electric teakettles, securing a babysitter for parental moviegoers, getting to the airport for airlines, or opening a ream of paper for your home copier.

You should also probe the largest tier of noncustomers. When major television manufacturers wished to enter the South African market, for example, discussions with rural residents revealed that the key block to purchasing a television for them had nothing to do with the television itself. It was the fact that only a small fraction of the population had access to electricity. Selling car batteries with televisions unlocked an ocean of new demand. This type of insight can only be gained by interviewing and directly observing the challenges faced by noncustomers. Exhibit 10-4 outlines the action steps of path four.

Exhibit 10-4

Path Five: Rethink the Functional-Emotional Orientation of Your Industry

| Red Ocean Lens: | Blue Ocean Lens: | |

| Focus on improving priceperformance within the functional-emotional orientation of your industry |  |

Rethink the functionalemotional orientation of your industry or target industry |

Competition in a given industry or strategic group tends to converge, not only around an accepted view of the scope of an offering, but also around the bases of its appeal. Some industries and groups compete principally on price and functionality: Their appeal is functional. Others compete on generating positive feelings: Their appeal is emotional. A new value-cost frontier can often be opened up by shifting the appeal of a product or service from one basis to another, or by blending the sources of its appeal.

To uncover these opportunities, you first need to get clear on the orientation of your industry. Sometimes this is easy. High-end fashion, for example, has a clear emotional orientation aimed at making people feel both beautiful and elite. But other times industry players are so accustomed to its orientation that they no longer “see” it; they simply take it for granted. To get clarity, ask customers and noncustomers to describe your industry’s offering in their words, not yours. Doing this will give you a grounded understanding of whether it is functional or emotional, and what those adjectives mean in a given industry context.

Take the legal industry. When we query customers, the overriding response is that the industry has a functional orientation. It does not aim to generate positive emotions. But what does functional mean in this context? It gets the job done—no more, no less. For many people, however, the way the legal industry functionally “gets the job done” simultaneously triggers negative emotions. The top three responses that come back repeatedly are: intimidating (Who can read legal documents anyway?), complex, and overpriced (What industry charges by the minute and then rounds minutes up to a quarter hour?). Now think about the possibilities that could open up if the industry’s orientation were shifted to a positive emotional one. How does a legal product or service that is welcoming, simple, with price based on value delivered, not minutes spent, sound? To us, it sounds pretty great.

Or think about supermarkets. Again, the most common orientation is functional. Three descriptors that spring to mind are nuisance, necessary evil, and inefficient (think long checkout lines, slow service at the meat and fish counter, etc.). What could a supermarket be if it set out to shift this orientation to a positive emotional one instead? Think fun outing, stylish, and super-fast. That’s the gist of this path: getting you to reimagine your industry by shifting its orientation, which opens the floodgates to completely reconceiving your product or service offering.

To probe customers’ and noncustomers’ overall impressions of an industry, ask what they would say if they had to choose—functional or emotional. Then drill down to understand what their answer means in that context by asking for the three to five adjectives or characteristics that come to mind to describe it. Their responses can then point you toward the many factors that support and reinforce their impressions of how the industry presents itself. As you flesh this out, you may find that the way people actually see and experience how your industry competes may be very different than the way you see your industry. Then flip the question and probe interviewees (and your team members) on what the opposite characteristics would look like in your industry. This will provide insight into how to shift the appeal of an industry. Overall, this is a path most teams have a lot of fun applying. Exhibit 10-5 outlines the action steps of path five.

Exhibit 10-5

Path Six: Participate in Shaping External Trends Over Time

| Red Ocean Lens: | Blue Ocean Lens: | |

| Focus on adapting to external trends as they occur |  |

Participate in shaping external trends that decisively impact your industry or target industry |

External trends affect every industry over time. Nowadays there is hardly a business, nonprofit, or government agency whose world is not being reshaped by external forces. Think of the rise of social media, the growing obesity crisis, the global environmental movement, or aging populations in many developed countries.

Many companies try to project external trends themselves, and they pace their actions to keep up with the trends they’re tracking, adapting to them as events unfold. Projecting trends seldom provides insight into opening up new value-cost frontiers, however. Looking at how a trend will change what customers value, and how it might impact a company’s business model over time can. As Netflix saw Internet broadband explode, for example, it realized that fast, real-time streaming of full-length films would soon be able to take off. That meant the possibility of instant viewing gratification and complete viewing flexibility. You could change what you watched on a whim. It also meant convenience and ease. No need to preorder DVDs, wait for their arrival, and then mail them back. In other words, no need for Netflix’s original business model. This insight inspired Netflix to create a leap in value for buyers, via on-demand viewing, and a new blue ocean for itself. By looking across time—from the value a market delivers today to the value it might deliver tomorrow—companies like Netflix can more actively shape their future and lay claim to opening up a new value-cost frontier.

The aim of this final path is to help organizations go beyond adapting to external trends to participating in shaping them. Learning which trends to focus on is crucial, however. So is knowing the right questions to ask. The first thing you need to get clear on therefore is which trends decisively impact your industry. The fact that a trend is having a major impact on other industries or society does not mean it is necessarily relevant to yours. In one organization, for example, the team identified the growing power of the millennial generation with its very different wants and needs. True, the implications of this trend are enormous for many industries; but not, within a meaningful time frame, for theirs—real estate for retirees. Understanding and detailing the implications of each trend specifically on your industry, not the world in general, are key.

Not every trend, even if it’s relevant, is one on which a blue ocean can be built in an opportunity-maximizing, risk-minimizing way, however. This brings us to the other two questions you need to ask: Is the trend irreversible? And is it evolving down a clear trajectory? Oil prices decisively impact many industries, for example, and if they have been dropping significantly for many months that may be a seductive trend. But if you can reasonably imagine the price going up in another 6 to 12 months, and industry experts agree with that hypothesis, building on the trend would be unwise. Moving forward with a blue ocean initiative will be highly risky if, as in the case of oil prices, there is a high level of uncertainty about how the trend on which it was based is likely to evolve, or if the trend can be easily reversed.

For trends that satisfy all three criteria, ask, If this trend were taken to its logical conclusion, how would it impact the value we can deliver to buyers? And what would the implications be for our industry and organization? As Groupe SEB applied this path to electric home French fry makers, for instance, the key trends of rising obesity and healthy eating jumped out. The team then realized that existing customers of electric home French fry makers had never voiced this concern in customer surveys, as they had simply taken for granted that fresh French fries meant high calories and high fat. With this new understanding, the team explored the identified trends with noncustomers. This is the time when the team could clearly see the opportunity of unlocking an ocean of new demand by making a fryer with no frying.

Insight on how decisive trends will impact an industry can often be found by looking at other industries that have been, or are being, impacted by the trend. Disintermediation, deregulation, and the emergence of two-sided markets are all examples of trends that many industries have already been swept by. Their experiences can provide compelling insights into what might become possible for your organization, and how you might capitalize on this trend by changing the definition of value in your industry.

The question we hear most often about this path is: “How far into the future should we be looking?” The relevant question back is: “How long would it take you to tool up to produce and launch a completely new offering that will offer buyers a leap in value?” Your answer to this question will indicate how far forward you should be thinking if you want to leverage a decisive trend. The period most often used is three to five years.

The most difficult aspect of this path is getting clear about how a particular trend will affect the value of an industry’s current offering, or what a future offering will need to take into account. While the path itself is easy to grasp conceptually, the solutions are not as obvious as they are in the other paths, where the work usually yields a robust initial list of factors that could be changed. To address this problem, the team should consider each relevant trend in turn and ask, “If this trend continues as it has begun, what about our current offering will no longer make sense and might even detract from buyer value, and therefore should be eliminated or reduced?” And “What in our offering will we need to create or raise to deliver a leap in value to buyers?” Exhibit 10-6 outlines the action steps of path six.

Exhibit 10-6

Applying the Six Paths Framework

Athletes often remind themselves that there is no gain without pain. The same is true when it comes to using the six paths framework. The results are eye-opening and often revelatory. But be prepared: Generating those results takes time and effort in the form of multiple one-on-one interviews and observational fieldwork. While this is the most time-consuming part of the blue ocean shift journey, this is work that team members cannot delegate to anyone else—inside the organization or outside it. There is no outsourcing the team’s ears or eyes. Because the insights gleaned from the paths come from the team’s own fieldwork, these insights are empowering and build conviction. So don’t be tempted to short-circuit the process. If you do, you will undermine the initiative, and shortcut yourself and the insights gained, as well as the potential for successful execution, which is the aim of the entire initiative. Here is how this step unfolds.

Start with the big picture

Begin by explaining that the objective at this stage remains the big picture: The team is looking for insights that will provide clues as to how they might reconstruct their industry’s boundaries and open up a new value-cost frontier. They are not yet looking for final answers. The six paths will guide them on the type of insights they need to search for.

This reminder is important, because if team members feel the objective is to straight out search for solutions, many will easily be discouraged when answers do not jump out at them and become frozen by the sheer weight of what is being asked. Remember, this process is very different from what most organizations do to develop strategy. If people feel frozen or discouraged as they meet the market, they will tend to go through the process perfunctorily, instead of being inspired and inquisitive. So you need to make this fun, and let everyone know that now is the time to be a detective and uncover clues. Reassure them that feeling a bit uncomfortable is to be expected and they’re not alone in feeling that way.

Divide the team into two subteams

Exploring each path takes time. Asking the entire team to explore each of the six paths is typically asking for a time commitment few can make unless their schedules have been significantly cleared for this initiative. By having each subteam explore only three paths, this step becomes much more doable. It creates a healthy sense of competition, as to which subteam will do the best job, which contributes to fun and the quality of insights garnered. It also mitigates complaints that the assignment is unfair and not feasible in light of team members’ regular responsibilities. Explain this reasoning to the team up front, as the subteams are being set up. That way they can appreciate that you understand what is being asked of them; that you expect high-quality work; and that you have also taken practical measures to make this step feasible and motivating by creating the subteams. Silence is not golden. Explain the concept behind the subteams.

Walk the team through the entire framework

Now walk everyone through the full framework and explain what the subteams will be exploring along each path. It’s key for everyone to have a good overview so that they can respond intelligently to others in the organization who ask about what’s happening. Knowing what both subteams are working on will short-circuit the fear and anxiety that can easily get sparked if someone answers, “I don’t know. The team leader hasn’t shared that with us.” Subteam members will also appreciate being treated as equal partners whose understanding matters. The result: more commitment, less fear, with subteam members naturally able to keep the rest of the organization in the loop.

Explain how the process will unfold

Once everyone understands the logic of all six paths, the subteams can get their assignments. You can make these yourself or, and this is often preferable, you can let the teams select the paths they’ll work on randomly, via a draw. This way, they choose their own paths, and the process feels fair. Subteam members should agree on which path they will tackle first, and move on to the next path only after that one has been completed.

Members of each subteam should then develop work plans for their assigned paths, beginning with the one they will tackle first. Start by reviewing the logic of each path and the associated action steps, as outlined in exhibits 10-1 through 10-6. To help you effectively perform this task, the relevant materials and templates are provided for your free download and use at www.blueoceanshift.com/ExerciseTemplates. The templates will provide direction on the right questions to probe, as the subteam members go into the field to interview noncustomers and customers. The templates will also help them organize the insights gained in a meaningful way.

To explore each path, team members should begin working individually, then come together to synthesize their insights, then work individually again to gather a broader range of insights that they will subsequently pull together as a team. This sequence allows for the richest array of independent insights to emerge, via the individual work, while at the same time enabling the members to work together to uncover key patterns and identify interesting anomalies across their insights.

For path one, for example, subteam members will first develop their own list of key alternative industries and only then get together as a team to agree on the most relevant one(s) to explore, based on the criteria given for that path. Then each of them will individually interview customers and noncustomers, as prescribed in the path’s steps, before coming together to compile the findings. In this way groupthink is avoided and collective wisdom is achieved. A variation of this work pattern applies across the other five paths as well.

As part of the work plan, subteams should get clear on which noncustomers and customers to observe and interview in the field. You don’t want subteam members interviewing and observing the same people. Going back to path one, for example, suppose long-haul carriers was the alternative industry the subteam had chosen to analyze. Then you want to ensure that members of the subteam speak to the customers of different carriers by deciding which members will speak to the customers of which long-haul carrier. (These people are effectively the noncustomers of the focal industry.) As part of the fieldwork, take photos, video what you observe, and visit shops. In other words, get real in the field. Going back to long-haul carriers, for example, we’d recommend going to the airport, and speaking directly to people after they’ve checked in for long-haul flights. We’d also recommend speaking to airport staff involved in check-in and getting their views on why people choose to fly long haul over whatever alternative you are comparing it to. Think of yourselves as detectives. Have fun, and stay focused on the task at hand.

How many people should each subteam member interview per path? Typically, the number is 10 to 12, though some subteams do as many as 15 interviews each, because they find the learning so rich and inspiring. The first interviews for the first path a subteam tackles are usually the toughest, as most team members will be learning a new skill set. So remind them not to get discouraged and just to carry on. By the end of the interview process for a given path, each member should have started to hear some themes in people’s responses, as well as a few idiosyncratic responses, which often prove useful as they come together to share their results. So be sure to record these outliers and not pooh-pooh them. The six paths interview work can make people feel awkward, or even squeamish at first, if they’re accustomed to understanding customers via large-scale surveys. Let them know you appreciate that, but ask them to persevere. We have never encountered people who were not soon rejuvenated and awed by what they learned by doing this fieldwork.

To maximize the insights gained, remind team members not to “sell.” Observe, follow, and ask with due humility. It’s imperative that members stay open, and not get defensive as noncustomers and customers start to convey honest responses to their questions. If negative comments come back, probe deeper to extract the most learning. Stress to the team that negatives are opportunities in disguise. So they want to get super-clear on what they are and why they arise. Remind members to record and capture all the insights and answers for every person met, observed, and interviewed in real time, not later, when memories can become cloudy. The objective is to see the world with new eyes. No observation is too small, as many seemingly small observations can later add up to the big insight that creates a blue ocean. Think of how the small and repeated observation of lime scale in the UK’s municipal water led Philips Electronics to create a blue ocean by introducing replaceable filters.

Paths one, two, and three indicate the relevant noncustomer groups to interview and observe—those in alternative industries, strategic groups, or buyer groups, respectively. For paths four to six, subteams should interview people in the largest tier or the largest two tiers of noncustomers identified in step three of the process (see chapter 9). Whether one or two tiers are chosen depends on the relative size of the tiers. When one tier clearly looms far larger than the other two, we recommend focusing on that tier alone. When that isn’t the case, focusing on two tiers works well.

What’s Next

After completing their live-action market explorations, the subteams will be armed with a wealth of new insights on how value can be unlocked in innovative ways. Inspired by what they’ve learned in the field, most of the members will also be intellectually energized by the new ways of thinking they’ve just been exposed to. This brings us to the second part of step four, where we’ll show you how the team will use the insights they’ve gathered to craft concrete, alternative blue ocean moves. Here we will introduce the eliminate-reduce-raise-create grid, which is key in breaking the value-cost trade-off and opening up a new value-cost frontier. Let’s keep moving.