ANYONE WHO HAS been away, especially for a long time, must adjust to dealing with issues left unresolved, catch up on friends and obligations, and carefully review new experiences and ideas in the light of conditions at home. Evelyn, ‘so near home’ (albeit in France), confronted the same needs. During the next thirteen years before the Restoration, to which he looked forward though at times with little confidence, he attended to what was in effect a virtual résumé of both his European tour and its adaptation to the conditions of his own country and times. He addressed matters to do with family, cultivated and expanded the circle of his friends and drew into it a world of other intellectuals. And he married.

In particular, he needed to find a place where he could settle, raise a family and cultivate his own ground, where he could implement some of what he had learned from French and Italian gardens. Wotton was of course out of the question as a home, so he sought a location where, in the true spirit of a ‘cabinet’-maker (that is, one who delights in collecting items for his cabinet), he could establish his own library and set out his collections of engravings, paintings, medals, even plants. He translated books that, seemingly of little import today, concerned matters that clearly affected him: books on politics, religion, science, philosophy, libraries, ancient and modern architecture, the characters of different countries, and some works on horticulture and arboriculture. At this time he also began to conceive of a major work on British gardening, the ‘Elysium Britannicum’, an endeavour that he would continue to augment for almost the rest of his life, but which remained unfinished.1

If his Diary of these years is often sparse, it may be attributed to his giving it less time during busy searches for where and how he wanted to be and to his increasing correspondence. After years of wandering he thought to settle down, but with unsettled times and his own sense of purpose constantly under review, that was not altogether easy, and his movements, though briefly noted, precluded much reflection in the Diary itself. If the Diary, which was revised or at least reviewed later, is silent, his often more private letters provide some insight into his current opinions, as do his publications that sought to domesticate new and non-English ideas.

In 1647 when he had returned to Paris, Evelyn could relax (‘the only time in my whole life I spent most idly’) and enjoy a round of visits and contacts, both new and established; he found the French capital lively and full of royalist and religious refugees. He read French books on liberty and on the making of libraries and, notably, on gardening, and friends urged him to address these useful topics for an English readership.

But he also was in the process of falling in love with Mary, the young daughter of the royalist ambassador, Sir Richard Browne, whom he had first met at the start of his European tour. They were married, with Church of England rites, on 27 June 1647, by a chaplain to the Prince of Wales (later Charles II) in a chapel of the ambassador’s residence. After some celebrations and more visits in and around Paris, Evelyn returned to England in October to reconnoitre the future.

Soon after his return he kissed the hand of Charles I at Hampton Court Palace, where, at the end of the First Civil War, the king was being held by ‘those execrable villains who not long after murdered him’; the king’s chaplain there was Jeremy Taylor. At Wotton he ‘refresh’d’ himself with family and friends. While abroad, he had learned of the death of George’s wife and his remarriage two years later in 1647, so there was much on which to catch up, not least the state of affairs at Wotton. George was now an MP and continued as a sitting member for Reigate until Pride’s Purge (December 1648) and the Rump Parliament, carefully playing both sides as both a passive royalist and commissioner for sequestrations. John also went to see his younger brother, Richard, who would also be married within a year, and his sister, who had married a barrister.

But he wanted a house, if not a home, of his own. In this political climate, land could be purchased reasonably, so Evelyn bought, sold or resold properties, but nonetheless for security he chose to ship some pictures and other portable objects to France. He visited the estate of Sayes Court in Deptford, occupied by an uncle of Lady Browne and looked after by a steward, William Peters. There his father-in-law allowed him to stay during this visit, and he re-ordered and catalogued Browne’s books.2 In the end it would be Sayes Court – though by no means an ideal home and one for which he continued to have issues with the lease – that Evelyn settled on as his choice. In 1652 he wrote to his wife (LB, I.128) that he was purchasing some land around it ‘not for any great inclination I have to the place’, but because it would allow him to develop its ‘other conveniences, and interest annexed to it’ (that is, the chance to make a garden). Eventually purchasing the lease and title to it allowed him later to send much-needed money to Sir Richard, who was short of funds and sometimes besieged in Paris during the disturbances of the Fronde. But otherwise his time in and around London was a whirl of visits, making some new friends, such as the botanist and bibliophile Jasper Needham and persons met briefly in Italy, like the physician George Joyliffe. The political and religious scene he viewed with much distrust, observing the many factions at work in the land and listening carefully to rumours, all the time reporting under a pseudonym (‘Aplanos’, that is, steadfast) to Sir Richard in France, writing to ‘safe’ addresses and telling him that he was ‘altogether confused and sad for the misery that is upon us’ (Correspondence, pp. 4 and 35).

Church services were proscribed or were conducted in secret. The Levellers were spreading like ‘a distemper’, and in May 1649 the ‘Parliament Act’ abolished the monarchy, and the king’s statues were ‘thrown down at St Paul’s portico and Exchange’. Later Evelyn inspected pictures seized from the royal collections by the rebels who sought to dissipate ‘a world of rare paintings of the King’s and his Loyal Subjects’. There were times when he wondered whether he should leave England altogether, but the pull of family, the link to Wotton, and his concern to write about matters that he thought important to his country made him loath to opt for a permanent break. Even as early as 1651 he wrote to his sister that ‘I might have one day hoped to have been considerable in my country,’ but now would settle for ‘A friend, a book, and a garden [that] shall for the future perfectly circumscribe my utmost designs’.3 This phrase about his future ambitions is one used on several other occasions; it suggests that being ‘considerable’ or useful in England had been, or might have to be, exchanged for that triad of very local pleasures.

He found time to sit for his portrait (a melancholy figure holding a skull) by Robert Walker (illus. 15), which was to be sent to his wife along with the beautiful little book of Instructions Oeconomiques, transcribed by his secretary and decorated with a frontispiece of a seated woman with a cornucopia, to which were added poems and recipes, and allusions to ancient scenery, like Seneca’s fishponds and the Garden of Eden – hope for their future, surely. He also got involved in a project to develop and patent a perpetual motion engine, a mechanical scheme that lured many to become involved.4 But he wished to return to France, so he obtained, with difficulty, a permit to leave from the regicide John Bradshaw, the President of the Council of State, and, after being ‘merry’ with his brothers at Guildford, left for France in July 1649.5 He was accompanied by his amanuensis, Richard Hoare.

Six months earlier, on 30 January, King Charles had been beheaded in Whitehall, outside Inigo Jones’s Banqueting Hall. While his brother George witnessed the execution, Evelyn stayed away and kept ‘his Martyrdom a fast’. A week before, Evelyn had risked being ‘severely threatened’ for publishing his translation of François de La Mothe Le Vayer’s 1643 pamphlet On Liberty and Servitude, ‘translated out of the French into the English tongue’. He later noted on his own copy that ‘I was like to be called in question by the rebels for this book being published a few days before his Majesty’s decollation’ (that is, beheading).6 He had found the tract in Paris, ostensibly a defence of the young Louis XIV, but its general thrust impinged much on the conflicts in England. His translation was dedicated to his brother George ‘of Wotton in the county of Surrey’ and signed only ‘Phileleutheros’ (that is, friend of freedom), though a dedicatory poem mentioned the translator by name. Evelyn told his brother that this publication was ‘the first time of my approach upon the theatre’.7 In ‘To Him that Reads’ he wrote that in these ‘licentious times’, with ‘impious offerings to the people’, Liberty was not an illusion, was no ‘Platonic chimera of a state, nowhere existent save in Utopia’, and that the reader must reject ‘verily [that] there is no such thing in rerum natura as absolute perfection’. Yet liberty can be realized, and he argued that for the last five thousand years there had been no ‘more equal and excellent form of government than that under which we have lived during the reign of our Gracious Sovereign’. No wonder the rebels might have censured him; but they were probably too preoccupied to notice a writer, as yet, unknown.

15 Robert Walker, portrait of John Evelyn, sent to his wife. Besides the skull, there are some stoical words of Seneca on a paper on the table, and a Greek inscription proclaiming that ‘Repentance is the beginning of wisdom.’

Back in Paris he was warmly greeted by friends, took communion with Mary – from whom he had been absent nearly two years – and went to kiss the hand of Charles II (as he now was) at Saint-Germain, before the king left to continue battles in Scotland. Evelyn travelled to meet the king in a coach with the Earl of Rochester and one of the king’s mistresses. He also paid his respects to the young Louis XIV. He needed to repudiate the rumour that he had been knighted (‘a dignity I often declined’). He visited more gardens and heard a good lecture at the royal physic garden. He met royalists like Abraham Cowley and John Denham, both attached to the now widowed Queen Henrietta Maria in Paris, and a cousin of Mary’s, Samuel Tuke, with whom he sought out gardens in the Île de France; Edmund Waller often came from Rouen to meet and talk with him in Paris.

He was also working on his essay on The State of France, spurred by ‘conversations’ with a friend.8 This contained remarks upon the virtues of travel and gave a rather dry account of French society and its monarchy, court, army and constitution, yet found that France does ‘rather totter than stand’ and was much subject to favouritism, with a slavish populace uninterested in trade or mechanical arts, and its children, ‘angels in the cradle’ were ‘devils in the saddle’ (MW, p. 78). Though he had got to know and like France, he was still quick to make comparisons with England, so that the River Seine was not ‘comparable to our Royal river of Thames’; he liked Paris’s streetscapes, but not its muddy thoroughfares, and found its air better that our ‘putrified climate, and accidentally suffocated city’ of London (by accidentally, he meant that its climate was sullied by the accidents or occurrences of burning sea coal, which he would write about in Fumifugium). The State of France was published in London in 1652 (although its concluding epistle is dated Paris, 15 February); on the title page of some copies was an engraved author’s monogram, where the initials JE lurk behind oak and bay leaves, a prophetic emblem for his later fame as the author of Sylva, or even perhaps for his sometimes reclusive self (illus. 16).9

16 Engraved monogram from Evelyn’s pamphlet The State of France (1652).

He returned briefly to England between June and August to settle ‘some of my concerns’; to observe how the now officially named ‘Commonwealth’ or ‘Free State’ was faring; to visit George, Richard and his sister Jane, who now had a son; and to witness soldiers around Wotton confiscating gentlemen’s horses ‘for the service of the state’. In late August 1650, after visiting Sayes Court, he was back in Paris mixing with royalists and exiles (‘a Little Britain and a kind of Sanctuary’10) and took his wife to revisit the mansion designed by François Mansart for the Marquis de Maisons; here he again admired the river prospect, the ‘incomparable’ forests, woods, the ‘extraordinary long walks set with elms’, and its ‘citronario’ (a term Evelyn invented) – the whole estate (‘all together’) not exceeded by any things he had seen in Italy.11 He talked with Thomas Hobbes, who had known Francis Bacon and whose English text of De Cive (Philosophical Rudiments concerning Government and Society) he was now reading. He heard sermons in Browne’s chapel, as well as a Jesuit preacher and ‘excellent music’ in their church on the rue St Antoine, discussed chemistry with both Nicholas Blanchot and Sir Kenelm Digby (the latter an ‘errant mountebank’, he decided at that point), took his wife to visit more gardens, and revisited the gardens and cabinets of Pierre Morin. He was also writing to his brother with suggestions for his ‘Garden at Wotton & fountains’. He was busy with visits, meetings with expatriate English, attending services, and even bathing with his wife in the river at Conflans. It was in fact a very exciting time and place, with expatriates coming and going and much intellectual exchange and opportunities for experimentation (Evelyn was pursuing chemistry and anatomy, and buying books). Some English converted to Catholicism, for the current circumstances in religion in England offered no immediate or even pleasing resolution; but others found themselves pulled towards England, even if the practice of religion there was threatened.

It was a troubled time even in Paris, with more, if different, political chaos than in England. But that made opting to return to England, to bury oneself in private, unostentatious and patient retirement, like Richard Fanshaw or Thomas Henshaw in the village of Kensington, not an easy decision for Evelyn to make; some friends urged him to stay put in France. Hearing on 22 September 1651 of Charles II’s defeat at the battle of Worcester (though Charles escaped and later got back to Paris), Evelyn decided that there was no hope for a restoration at home. Yet Evelyn himself was being lured to return by members of his family and by the steward at Sayes Court; in his Diary (III.59) he ‘was persuaded to settle henceforth in England, having now run about the world’ for almost ten years, and this he did (albeit with reservations) in January 1652. He would never again cross the Channel. By March that year he was arranging for his wife, now pregnant, to be brought over to England with Lady Browne, and he welcomed them at the port of Rye in Sussex.

They used Mary’s new coach to show her some of the Kent countryside while waiting a month in Tunbridge Wells for Sayes Court to be readied. The house needed much refurbishment, having been confiscated in 1649 by the Commonwealth, then sold, and Evelyn was seeking to buy the lease back, which he finally did on 22 February 1653. Sayes Court was now his own place, and in mid-July they finally moved in and enjoyed a warm reunion with John’s two brothers, their families and coachloads of friends. In August his son Richard was born there. But a month later Lady Browne died, after which, to distract her, he took a mourning Mary to visit Wotton for the visit time.

In the remaining seven years of the Commonwealth, cautiously preserving his own integrity without parading it, he settled to enjoy himself and survive under the ‘rebel’ Cromwell. He cultivated his family in its happiness and disappointments and helped with the education of his brother’s son, also called George, finding him a tutor in Christopher Wase, a relation of Mary’s. He worked on his house and gardens, increased his wide circle of friends and colleagues, attended carefully to understanding the character of his own country and continued to write and translate books or pamphlets that he found important and some whose publication was a particular and personal pleasure. He worked at translating the first book of Lucretius, which he had probably started in France when the task was urged upon him by friends there. It appeared in 1656. Two years later came his English version of Nicolas de Bonnefons’ Le Jardinier françois, dedicated to his fellow tourist Henshaw and where he first introduced the term ‘olitorie’ to refer to a kitchen garden, a garden space that he now possessed for himself.

He travelled the country with Mary in 1654 to visit some of her relations and to show her a country that she barely knew, having been brought up in France, but it was nonetheless a tour to satisfy ‘my own curiosity and information’ about England. And for the first time he also visited more ‘northern parts’. While alert to the ruinations perpetrated on the country, the ‘fatal’ sieges of towns like Gloucester and the cathedral at Worcester ‘extremely ruined by the late wars’, he was always curious about gardens, parks, woodlands, libraries and ‘monuments of great antiquity’. The cathedral at Gloucester was a ‘noble fabric’, the acoustics of its ‘whispering passage’, mentioned by Bacon in his Sylva Sylvarum, ‘very rare’. He was gladdened that York Minster alone among the great cathedrals of England had been ‘preserved from the fury of the sacrilegious by composition with the rebels’, a refrain he took up on several occasions, as when writing to Jeremy Taylor of ‘this sad catalysis and declension of piety to which we are now reduced’ (LB, I.160). He saw sugar refined for the first time at Bristol and admired the cliffs of the Clifton Gorge there, ‘equal to any of that nature I have seen in the most confragose [broken] cataracts of the alps’ (an oddly patriotic remark, since the cliffs there are hardly ‘confragose’). At Salisbury the canals were ‘negligently kept’ (by comparison with the Low Countries), and he found it difficult to number the stones at Stonehenge,12 a structure that he first thought was the representation of ‘a cloister’, but then saw as a ‘heathen & more natural temple’. Returning from the north via Cambridge, he admired the university town’s buildings and libraries, but found it ‘a low dirty unpleasant place, the streets ill paved, the air thick, as infested by the fens’. After a four-month journey of over 700 miles, they returned to Sayes Court.

One of the highlights of his English tour with Mary was a visit to Oxford. He heard speeches, disputations, sermons, dined at Exeter College, All Souls and Wadham, saw Archbishop Laud’s new quadrangle at St John’s, the chapel of New College ‘in its ancient garb, not withstanding the scrupulous of the times’, and the libraries at Christ Church and Magdalen, where the double organ in its chapel (anathema for Puritans) was played for them by Christopher Gibbons. Bodley’s librarian showed Mary and him old books and ‘curiosities’, and they went to the Physic Garden, where the ladies tasted ‘very good fruit’. Evelyn also visited ‘that miracle of a youth, Mr Christopher Wren’.

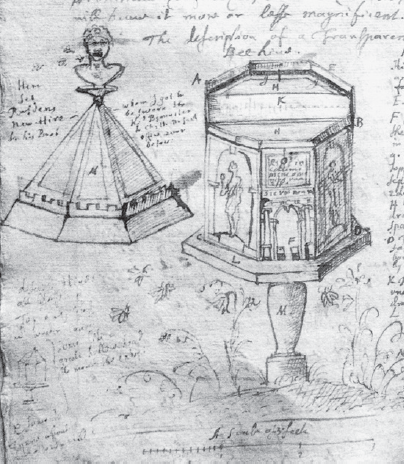

But among the particular pleasures of this Oxford return for Evelyn was his meeting with John Wilkins, the Warden of Wadham, who would show him a transparent beehive, an example of which he would proudly display later at Sayes Court and show off to the king, and which he discussed and illustrated (illus. 17) in Chapter XIII of the ‘Elysium Britannicum’; over a dozen pages were devoted there to bees and beekeeping (EB, pp. 273ff.), and in this he was sharing his enthusiasm with Samuel Hartlib, whose The Reform’d Commonwealth of Bees (1655) he cites. Wilkins also showed him the ‘gallery’ above his lodgings, where there were ‘Shadows, dials, perspectives . . . & many other artificial, mathematical, magical curiosities’. This was a time when virtuosi were exploring and experimenting with various instruments that would gauge rain and wind, thermometers and barometers, a pneumatic engine that performed sundry experiments, and a device for measuring a distance travelled (what Evelyn’s Diary called a ‘way-wiser’), an example of which would be presented by Wilkins to the Royal Society in 1666; some of these instruments and experiments were gathered in Wilkins’s laboratory.

17 A transparent beehive, from Evelyn’s ‘Elysium Britannicum’.

The ‘way-wiser’ had already appeared among the ‘20 Ingenuities’ in Samuel Hartlib, his Legacy (1651), a copy of which Hartlib gave to Evelyn when they first met in 1655. Hartlib was briefly and importantly at the centre of intellectual inquiries in England, and Evelyn learned more about him during that Oxford visit. Though within a generation of his death in 1662 Hartlib was ‘more or less forgotten’, his role in sharing, communicating and reforming ideas through what he termed his ‘Office of Address’ was considerable, and in many ways it animated numerous members of what would become the Royal Society. Yet it seems also certain that it took the various and collected members of the Royal Society, given its royal charter the very year of Hartlib’s death, to move ahead on more scientific and intellectual fronts than a single, though enterprising, man could promote singlehandedly, even with his connections.13 Nonetheless, the first governor of Connecticut, John Winthrop Jr, thought Hartlib the ‘great Intelligencer of Europe’, and John Dury, Hartlib’s great collaborator, emphasized his role as a facilitator, calling him ‘the hub of the axletree of knowledge’.

Born of German and English parents in Elbing, the Prussian first came to London in the 1620s, where after his permanent return in 1628 he seemed to be in contact with everyone of importance. He knew of Evelyn, for example, before they met in November 1655 and had noted down Evelyn’s interest in ‘husbandry and planting’, beekeeping and etching. When Hartlib eventually visited Deptford, he noted in his ‘Ephemerides’, the logbook of visits to English virtuosi, that Evelyn was ‘a chemist [who] hath studied and collected a great Work of all Trades’, and found that he spoke French, Italian and Latin, and had ‘many furnaces a-going and hath a wife that can in a manner perform miracles, so curious and exquisite she is in painting or limming and other mechanical knacks’. Evelyn did indeed establish a laboratory and maintain chemical notebooks, and had worked on and studied chemistry while in France;14 he was also planning a book on the secrets and mechanical recipes of various trades, on which he reported to the Royal Society in 1661, though it was eventually left unfinished; and his wife was undoubtedly skilful, receiving help in her painting from a visiting Frenchman, M. du Guernier. Evelyn, like Boyle, would call Hartlib a ‘good friend’,15 a ‘Master of Innumerable Curiosities, & very communicative’, but also, less warmly and much later, would say that Hartlib was though ‘not unlearned’, yet ‘zealous and religious; with so much latitude as easily recommended him to the godly party then governing’.16 Hartlib did, however, appeal to John Milton, who saw him as sent ‘hither by some good providence from a far country to be the occasion and the incitement of great good to this island’ and dedicated to him his book Of Education in 1644, which Hartlib had himself commissioned.

While Evelyn appreciated much of what Hartlib communicated about horticulture and gardening, he distanced himself from his evident and more radical commitment to a political reformation of England. But they were ‘an interesting duo’,17 seeing what was (in Milton’s phrase) ‘good to this island’, but in different ways and at different times: while Hartlib was a dominant and involved guide to gardening and horticulture during the Interregnum, his ‘closeness to the Cromwellian regime made him persona non grata at the Restoration’, where Evelyn’s concern was directed to making these matters both ‘royal’ and above sectarian ideology. The distance between their attitudes towards ‘God’s husbandry’ (1 Corinthians 3:9) was also an issue that came to preoccupy Evelyn, though in a slightly different way, when he came to confront the impact of Epicurus’ atomism on his faith.

Among Evelyn’s more arduous tasks during the early 1650s was a translation of Lucretius’ De rerum natura (On the Nature of Things). He had started on translating the Latin verses into rhymed couplets while still in France, where a French version in prose had appeared in 1650; its frontispiece was the model for Evelyn’s own, engraved by Wenceslaus Hollar after a design by Mary Evelyn (whose name is noted on the rim of a vase pouring forth waters, which ‘source’ does not appear in the French image). Evelyn’s Diary in 1656, when the translation appeared, noted that ‘Little of the Epicurean philosophy was then known among us’; that was not entirely true, as Howard Jones makes clear: Lucy Hutchinson had undertaken a translation in the early 1650s, though it remained unpublished at the time; Thomas Creech also published a full English version of this important text in 1682, to be revised later by Dryden.18 Evelyn’s translation was, in Jones’s phrase, ‘entirely forgettable’, but it is significant on two important counts: it enmeshed Evelyn in reconciling his faith with his scientific empiricism (specifically Epicurus’ physical theories of atomism), and this in turn had some direct impact upon his inability to bring ‘Elysium Britannicum’ to any conclusion (this second point is taken up in Chapter Ten).

Epicurus enjoyed (at least for some) the reputation of prioritizing sense impressions (the Greek for which translates as ‘fantasia’) – the atomic succession of images upon our senses, particularly that of sight, which was Aristotle’s prime organ of reception. But he also had the reputation of celebrating the ‘luxurious and carnal appetites of the sensual and lower man’, or, as one opponent of Epicurus put it, ‘the whole sum . . . of his Ethicks . . . is . . . that pleasure was the alpha and omega of all happiness’ (quoted Jones, p. 200). This was therefore, if not plain atheism and impiety, of dubious appeal to Christians like Evelyn. But on the other hand, what was advanced in support of Epicurus was his evident empiricism, that the house of nature that he explored was primarily founded upon atomism (‘small atoms of themselves a world may make’19). Moreover, Bacon, to whom Evelyn was always indebted, had himself explored atomism, at first sympathetically, in Cogitationes de natura rerum, where the ‘doctrine . . . concerning atoms is either true or useful for demonstration’, because it is through material things rather than thought that we grasp the ‘genuine subtlety of nature’. In his ‘On Atheism’ in the Essays, Bacon also argued that the school of Epicurus ‘is a thousand times more credible, [in that] that four mutable elements, and one immutable fifth sense, duly and eternally placed, need no God: then that an army of infinite small portions of seed unplaced [that is, atoms] should have produced this order, and beauty, without a divine marshal’. Bacon came to modify those ideas by the Novum organum of 1620, where a ‘doctrine of atoms’ will hypothesize ‘a vacuum and . . . the unchangefulness of matter (both false assumptions)’ (Jones, pp. 183–4). Bacon’s Cogitationes de natura rerum saw publication only posthumously in 1653, while Evelyn was at work translating the first book of Lucretius.

Yet that very year (1653) Evelyn sent a manuscript of his translation to a cousin, Richard Fanshawe, who praised his work, significantly, because its ‘exactness’ would happily prevent Lucretius from eluding those who accused him of irreligion – ‘no running away now, no denying the fact for which he is accused’.20 Yet in April 1656, when Evelyn’s translation was in press, Jeremy Taylor regretted his embarking on the work and hoped it would meet with his own ‘sufficient antidote’. Evelyn attempted to assuage his ‘ghostly confessor’ by hoping that his own ‘animadversions upon it will I hope provide against all ill consequences’, promised ‘caution’ and thanked Taylor for his ‘counsel’. In that year, though, was also published Walter Charleton’s Epicurus’ Morals, where its author – physician, royalist, true believer in English Protestantism – gave support for Epicurian philosophy as a basis for human happiness.

So even as Evelyn let his translation of the first book of Lucretius proceed through the press, he was confronted both by others’ scepticism and by his own hope that somehow he could reconcile his faith with Lucretius’ empirical responses; the Epicurian emphasis clashed with the approaches of both Bacon and Evelyn’s future colleagues in the Royal Society. Yet the appearance of his book was heralded with pages of support and encouragement – a usual habit in those days; but they seem, at least in retrospect, to have been a response to a nervous need to obtain endorsements – from his father-in-law, from Edward Waller, from Christopherus Wase (in Latin) and the letter in support from Richard Fanshawe. To some of these Evelyn himself responded both in his introduction (‘The Interpreter to Him that Reads’) by insisting that Lucretius nonetheless ‘persuades to a life the most exact and moral’, and by printing marginal comments to affirm ‘not that the Interpreter [that is, translator] doth justify this irreligion of the poet, whose arguments he afterwards refutes’. But that was more easily stated than argued. Yet at least it was a plausible attitude to adopt, and one year later Charleton’s dialogues on The Immortality of the Human Soul cast Evelyn in the person of ‘Lucretius’, who was to make the argument that ‘atomism’ was a proof of God’s existence.21

Epicurus, in Evelyn’s own version, did indeed penetrate with courage and wit the ‘remotest doors’ of the natural world, to the extent that the Englishman had to confess that he could not manage adequately to render the ‘Greek’s obscure conceptions’ into English (maybe the rhymed couplets cramped his usually fastidious style).22 Between the unique world of God’s Creation and a scientific probing of its complexities and the material atoms of the natural world, Evelyn wavered. In this, he was unlike Robert Boyle, whom he first met at Sayes Court in April 1656, for Boyle was both an ardent Christian and a keen scientist; but more akin to Jeremy Taylor, who preferred Evelyn’s religion to his scientific scrutiny (in part because Taylor did not share the latter). When Evelyn used the epitaph for Pierre Gassendi at the end of the first book, it must have seemed suitably affirmative, since the late scholar and Christian was also an ‘Assurer of Epicurus’s Institution’.23

At least one of the encouraging remarks appended to his translation would seem ambiguous, maybe even double-edged, and Evelyn was alert enough to register the difficult waters into which he was wading; enough to question his commitment to publishing the remainder of the original. The commendatory lines lent by Waller to grace Evelyn’s translation made much of Epicurus’ determination to expand his inquiry, to throw down (‘dispark’) the fences (‘pale’) of a traditional garden world:

For his immortal boundless wit

To nature does no bounds permit;

But boldly has removed the bars

Of Heaven, and Earth, and Seas and Stars,

By which they were before suppos’d

By narrow wits to be inclos’d,

’Till his free Muse threw down the Pale,

And did at once dispark them all.

But this decorous compliment concealed a more disturbing idea: that Epicurus had breached conventional boundaries, thrown open the world of the ‘park’, previously enclosed and circumscribed by ‘narrow wits’, and so removed all the constraints that heaven and earth imposed upon an inquiry into the realm of nature:

Lucretius with a stork-like fate,

Born and translated in a state,

Comes to proclaim in English verse

No monarch rules the Universe;

But chance and atoms make this all,

In order democratical,

Where bodies freely run their course,

Without design, or Fate, or Force.

In those opening lines Waller touched upon a disturbing new vision of the world – with no monarchy, all chance, democracy. So we have ‘as antipathetic a conclusion as it is possible to imagine for a man of Evelyn’s stamp’;24 Evelyn himself wrote ‘that out of nothing, nothing ever came’. That he could not bring himself to publish the rest of his translation of Lucretius was in itself important, not least because he was frustrated in bringing into English a book of extreme scientific relevance at the time. But it was also, arguably and indirectly, a roadblock to his work on finishing the ‘Elysium Britannicum’, especially when it was subtitled ‘or the Royal Gardens’: for an appeal to royalty implies an appeal to English religion. While he finished his translation of most of Lucretius and was publishing its first book, he wavered endlessly about committing the rest to the press: he blamed his printer in several letters for its mistakes, sometimes pondered the issue of a second and ‘more careful edition’, and at other times ‘determined to proceed no further on that difficult author’ and ‘rude poet’, whose fourth book disturbed him with its explicit sexual matter and animadversions on the soul, which he could not accept.25

It might have been better to have concentrated his energies on his ‘History of all the Mechanical Arts’, which people like Hartlib and Boyle urged. This was an elaborate index of ‘secrets and receipts mechanical’ that he collected himself and for which he sought help from others to provide him with further materials. These were categorized under trades (artisans, engineers, architects, shipwrights, stonemasons and so on) and status or occupation (midwifery, laundry-making, sewing, women). That enterprise too was left incomplete, though for reasons unconnected with his faith, and more likely with his unwillingness to take on the sheer bulk and intricacy of collecting sufficient evidence, when his ‘Elysium’ needed the same attention and correspondence. Indeed, it seems possible that Evelyn’s gardening and horticultural writings, always at the very centre of his intellectual and domestic life, were simply his preferred focus upon what was, after all, one element of the greater history of trades.26

Indeed, by the end of the 1650s he was engaged in another and more congenial translation, of Bonnefons’ Jardinier françois into The French Gardiner (1658), in which he thanks his good friend Thomas Henshaw (‘as a lover of gardens’) for urging him to do it; those personal touches of the dedicatory epistle were eliminated in the next edition, part of his sense that the book was important and should move beyond merely personal regard. It was, he wrote, published ‘for the benefit and divertissement of our country’. The first three issues of the first edition announce the French author only by repeating his initials backwards, and in the editions thereafter that was omitted entirely and the book became, so to speak, Evelyn’s own; he affects a pseudonym (‘Philocepos’) in the first edition, but still signs the dedication with his initials; his full name appears on the title page of the second and subsequent editions. The dedicatory epistle explains that the French text dealt well with ‘the soil, the situation, and the planting’, but that what he himself was moved to do was to use his own firsthand experience to introduce what he termed ‘the least known (though not the least delicious) appendices to gardens’:

such as are not the names only, but the descriptions, plots, materials, and ways of contriving the ground for parterres, grots, fountains; the proportions of walks, perspectives, rocks, aviaries, vivaries, apiaries, pots, conservatories, piscinas, groves, cryptas, cabinets, echoes, statues, and other ornaments of a vigna, &c. without which the best garden is without life, and very defective . . . (MW, pp. 97–100)

That treatise would indeed make him the ‘first propagator in England’ of ‘flowers and evergreens’, ‘palisades and contr[a]-espaliers of Alaternus’, and the ‘right culture of [incomparable verdure] for beauty and sense’. And he glosses such terms as ‘espalier’ (palisades), then in a margin note explains this as ‘pole-hedges set up against a wall, much used in France’. He omitted sections of the French text that discussed cooking, averring that he had little experience of the ‘shambles’, and he also protested that he has probably mistaken or had chosen to omit English names for French fruits. So The French Gardiner was, thus, Evelyn’s first publication on gardening matters, at once a distraction from the problems in Lucretius and a new commitment to focusing on the hortulan world. Its second edition in 1669 appended The English Vineyard Vindicated, to which Evelyn himself added some pages on the ‘making and ordering of wines’.

Despite his immersion and inquiring into matters scientific, Evelyn was, all the while, chafing at the repression of Anglicanism, convening services in his own house, and constantly preoccupied with bad sermons elsewhere and what he termed ‘extempore prayers after the Presbyterian way’. His Diary constantly listed the topics and emphases of sermons and advised that he should consult the notes he had taken after hearing them.27 In 1657, despite an ordinance that proscribed Christmas celebrations in London and Westminster, Evelyn and his wife went there to celebrate the festival; at a congregation for the Anglican service and sermon in a private chapel at Exeter House they were challenged by soldiers and held prisoner, whereupon two officers loyal to the new regime demanded of Evelyn why he dared to observe ‘the superstitious time of the Nativity’; Evelyn got off by saying that, far from praying for Charles I, he was actually praying for all ‘Christian Kings, Princes & Governors’ and pretended not to know that the Spanish king was a papist!

Meanwhile, Evelyn was working on A Character of England,28 a wonderfully self-critical and yet ironic attack on some of his cherished beliefs. It also suggests how much Evelyn could enjoy himself even in his writings as well as (at least by his own report) being funny and ‘merry’ in company. The supposed French author whom Evelyn ‘translates’ finds most of England appalling and distasteful, and Evelyn writes that on his first finding this ‘severe Piece, and [reading] it in the language it was sent me’, he thought it would honor our country most if it were suppressed, ‘as conceiving it an act of great inhumanity’. But ‘upon second and more impartial thoughts[!], I have been tempted to make it speak English, and give it liberty, not reproach, but to instruct our Nation.’ It seems that much of what the ‘French’ writer impugns in the English are things that Evelyn himself might find distasteful. While the Frenchman admits (as would Evelyn) that Inigo Jones’s Banqueting Hall and (the old) St Paul’s are admirable, that is as far as ‘he’ will go: ‘he’ finds that Hyde Park lacks ‘order, equipage and splendor’ and in Spring Gardens they ‘walk too fast’.29 The English are rowdy and unpleasant (Evelyn may have agreed), they drink too much ale, and are constantly toasting. But the thrust of the ‘Frenchman’s’ attack is on the Presbyterians’ theology and behaviour in church, manners introduced by the Scots and, beyond that, to all other ‘pretenders to the Spirit’ – the ‘madness of Anabaptists, Quakers, Fifth Monarchy Men and a cento of unheard of heresies besides’.

It is great fun to read, and one rhetorical strategy anticipates – and the comparison is not unfounded – Jonathan Swift’s A Modest Proposal. In 1729, advocating the economical and dietary usefulness of eating young children, Swift would support his arguments with an assurance of ‘a very knowing American of my acquaintance’ that juvenile cannibalism had sound social and economic merits. Evelyn similarly defends the French attack (which he himself has concocted) not only by relying on the precedent of satires by Juvenal and Persius, but by noting that he had been ‘reliably informed [on this matter] by a person of quality, and much integrity’, namely a lady who was herself an ‘auditor’ in a congregation when the preacher of a ‘serious sermon’ advanced the same ‘French’ strictures against the English! Evelyn tells his female reader to whom he presents his translation that some others (that is, Evelyn himself in what follows) might better access England’s character than this ‘whiffling capon-maker’ or ‘Gallus Castratus’.

The wit and humour of this Character are in sharp contrast to another book, in this case an actual translation, that Evelyn published in the same year, 1659. Evelyn must himself have sent both books to Jeremy Taylor in June, for Taylor thanks him for ‘his two little books’, the second of which was Evelyn’s own translation of the Greek text of St John Chrysostom’s Golden Book Concerning the Education of Children, a recently discovered manuscript which had just been printed in Paris in 1656. It was by translating this text that Evelyn solaced himself after the death of his young son Richard, aged five, in January 1658. Taylor wrote to him that it ‘made a pretty monument for your dearest, strangest miracle of a boy . . . an emanation of an ingenuous spirit; & there are in it observations, the like of which are seldom made by young travelers’ (Correspondence, p. 112).

Infant mortality and death of the mother in giving birth were sad and too-familiar incidents in seventeenth-century England,30 and Evelyn and his family were not spared them. His sister would die in childbirth, as did the child. His wife had already had a miscarriage in France before the safe arrival of her son, Richard, in Surrey. And three weeks after Richard’s death, another infant son also died. Evelyn’s and Mary’s distress was intense, and many friends shared the sorrow of their loss. His praise of Richard and his unfulfilled hopes for him were vividly penned in one of the lengthiest passages in his Diary (III.206–9). Much of that Diary entry was then echoed in his translation of the Greek text, where he addressed how a child might be educated.

In dedicating the Golden Book to his brothers, Evelyn recalled Plato’s remark that ‘those who are well and rightly instructed, do easily become good men’. But it was a terrible irony for Evelyn that the education of his son, to which he had devoted himself, was hardly ‘complete’ by the time of his death. Indeed, while recalling that both his brothers had lost infants, he had himself engaged with and taught what he called a ‘hopeful child’. He dilated upon Richard’s ‘early piety, and how ripe he was for God’, his skill with languages, learning to read both books and manuscripts, his delight in music and pictures, how he listened attentively to sermons and learned verses by heart. Evelyn recalled a young boy who seemed a better emanation of himself; yet his father-in-law had worried that the father was ‘over charging’ the young boy, whose ‘tabula rasa [was] easily confounded’.31 The work of translation may have consoled him, but at the end of his dedication to his brothers he broke down: ‘my tears mingle so fast with my ink, that I must break off and be silent.’ The young Richard was buried at Wotton.32

Excitement, confusion, rumours and countermoves about the Restoration were reaching a climax in 1659. Richard Cromwell, son of Oliver, had abdicated as Protector in May, and, fearing that there was ‘no Magistrate [that is, supreme ruler] either own’d or pretended’, Evelyn called for God’s mercy to ‘settle us’. He took lodgings in London’s Covent Garden for the winter and relied heavily on the comfort that sermons provided – those that advised that ‘reaping was not to be here, but at [postponed to] the end of the world’, or on ‘the Superiority of the Spiritual part’ (Diary, III.234).

In November 1659 Evelyn published An Apology for the Royal Party.33 Noting in his Diary that ‘it was capital [offence] to speak or write in favour’ of Charles II, he used a supposed letter ‘To a person of the late Council of State’ written ‘by a Lover of Peace and of his Country’ (as the title page announced) to make an impassioned and eloquent attack against the parliamentary party; it was also a rebuke to a pamphlet that was circulating in late October – The Army’s Plea for their Present Practice: tendered to the consideration of all ingenuous and impartial men, and Evelyn’s response was signalled on his title page as ‘A Touch [that is, stab, as in fencing] at the Pretended Plea’; his Diary recorded that the Apology was ‘twice printed, so universally it took’.

In January 1660 Evelyn tried to persuade an old schoolfriend, Colonel Morley, the Lieutenant of the Tower of London, to side with the king, presenting him with a copy of his Apology. Morley declined his approach, but later in May, when Charles II was proclaimed, came belatedly to seek Evelyn’s help in procuring a pardon for ‘his horrible error and neglect of the counsel I gave him’.

Later from February until April Evelyn was exceedingly ill, and doctors feared for his life. But he revived himself sufficiently to write a lively and tough response to the journalist Marchmont Needham, whose purported news in letters from Brussels defamed the king and worked against his restoration; the restoration was (Evelyn wrote) the ‘hope and expectation of the General [Monck] and Parliament recalling him, and establishing the government on its ancient and right basis’. Evelyn’s Late News from Brussels Unmasked was published in April 1660,34 after which he retired to the ‘the sweet and native air of Wotton’. Late News is lively and witty journalism (‘a rat is found out by his squeaking’), while rebutting ‘your forged calumnies’ and the invented letters with agility and confidence. The so-called News

will freight his soul down to that place of horror prepared for him and his fellow regicides, his pin, crust, and dog, dam and kittlings, and the concealed nuntio and all that sort of enigmatical and ribald (yet very significant and malicious) drollery . . . The filthy foam of a black and hellish mouth, arising from a viperous and venomous hearts, industriously and maliciously set upon doing what cursed mischief lies in the sphere of his cashiered power . . .

After this, more level-headedly, Evelyn responds with praise of the king, effectively identifying his good birth and extraction and that he is ‘obliging in his friendships’, a man like ourselves, not to be chased from ‘an ample and splendid patrimony’. Its affirmation of the state’s supremacy subtly mirrors the virtues of family: a ‘loyal Protestant Christian’ nation hopes for a ‘right Pilot [to] come at the head and stern’ of the new ship of state, as a father does his household.

In May ‘came the most happy tidings of his Majesty’s gracious Declaration [of Breda], & applications [that is, Charles’s letters] to the Parliament, General, & people &c and their dutiful acceptance & acknowledgement, after a most bloody & unreasonable rebellion of near 20 years’. Evelyn was still too weak to accept the invitation to travel to Breda to accompany the king back to England, but by May he was well enough to stand in the street to see the triumphant return to London on 29 May, ‘after a sad, & long exile, and calamitous suffering both of the King and the Church’. The roads were covered with flowers, the bells were rung, tapestries hung from windows and a fountain ran with wine. Evelyn grossly exaggerated the number of soldiers in the king’s procession, but like the Panegyric to Charles II that Evelyn presented to his majesty in April the next year, exaggerations might have been in order. Yet the Panegyric, extravagant in its ascription of wisdom and every conceivable virtue to Charles, must (writes Keynes in Bibliophily) have ‘caused Evelyn some distress if he ever read it again it later years’, not least when he came to realize that Charles had converted to Roman Catholicism on his deathbed. But now Evelyn was happy enough to organize a semiprivate meeting with the king, who received him graciously, after which he returned home to meet his father-in-law, also returned after nineteen years of exile as Ambassador to France.