THIS WAS TO BE EVELYN’s opus magnum, ‘my long-since promis’d (more universal hortulan work)’, as he wrote to John Beale in 1679 (LB, II.631–3). He probably started the project when settling at Sayes Court in the early 1650s, acquiring ground on which to make his own garden. His memories of gardens in Italy, France and the Low Countries were fresh and exciting, and the challenge to introduce these into England was compelling. Though he had other things on his mind during that decade – not least starting a family, trying to find a way to talk to his countrymen about the ‘character’ of both France and England, and responding to current philosophical ideas – he must have worked sufficiently on what he called the ‘model’ of his hortulan work to have drafted a synopsis or abstract. This he circulated to a variety of colleagues at the end of the 1650s.

To one of them, Sir Thomas Browne (whom he had not yet met), he wrote to explain his strategy, wishing to correct ‘the many defects which I encountered in books and gardens’, where expense was not wanting but ‘judgement’ was.1 Though he confessed his youth and ‘small experience’, he expected that ‘if foreign observation may conduce [that is, if he can be led by his observations of foreign gardens], I might likewise hope to refine upon some particulars, especially concerning the ornaments of gardens’; these he later listed as ‘caves, grots, mounts, and irregular ornaments’ that ‘do influence the soul and spirits of man’. There was both a specific English agenda – his ‘abhorrency of those painted and formal projections of our Cockney gardens and plots, which appear like gardens of paste board and March pane, and smell more of paint than of flowers and verdure’ – and a determination to unite the ‘useful and practicable’ with the philosophical. His aim was to address the ‘universality’ of garden-making, including practical matters that also ‘do contribute to contemplative and philosophical enthusiasms’. In this endeavour, he explained to Browne, he would invoke classical terms, the ‘rem sacrum et divinam’ (the sacred and divine) of ‘Elysium, Antrum, Nemus, Paradysus, Hortus, Lucus, &c’, as well as ‘ancient and famous garden heroes’. To that end, ‘a society of Paradisi Cultores, persons of ancient simplicity, paradisean and hortulan saints’ would emerge to constitute ‘a society of learned and ingenuous men’.

It was an ambitious project, and one that he had hoped might be published to commemorate the Restoration or to coincide with the founding of the Royal Society in the 1660s. The work drew the approbation of many who looked to his ‘finishing of Elysium Britannicum’, and a letter to that effect was circulated by Jasper Needham among ‘doctors & heads of Houses & others Oxon’ in January 1660. Those who joined their signatures to Needham’s were the two Bobarts, both named Jacob (the father and son who managed the Oxford Physic Garden), Philip Stephens, who revised its catalogue, Robert Sharrock, who had written on vegetables, and nine other scholars. Having seen the ‘grand’ prospectus that Evelyn had circulated, they clearly understood its essential ambitions, emphasizing ‘matters of great and common use & profit’ and themes ‘altogether new to our writers as having not been elaborated by any English’. They appealed to the ‘munificence of noble persons’ to equip the book with ‘figures and cuts proportionable to the nobleness & state of the piece’. This plea must have struck Evelyn as essential: both his Sculptura (1662) and the first edition of Sylva (1664) were to have very few plates, an obvious handicap for such works.

‘Elysium Britannicum’ was not a book that Evelyn would be able to produce on his own, not only because he needed funds for engraving, but because the range of ‘universal’ knowledge required him to seek, as he always did, help from many quarters. Travellers in Europe were encouraged to send ‘anything of new and rare which concerns agriculture in general, and gardening in particular . . . improvements [that] may be derived to our country’ (this request was sent to the tutor travelling with his nephew). Colleagues and friends at home, like John Beale, Hartlib, Abraham Cowley and Thomas Hanmer, all supplied advice and recommendations. Evelyn, busy in other ways, envied some of these colleagues happily withdrawn from the turmoil of court and politics who could concentrate fully on garden matters: he admired Cowley for his freedom ‘from noisy worlds, ambitious care and empty show’. Of Beale, he asked, ‘who but Dr Beale (that stands upon the tower, looks down unconcernedly on all these tempests) can think of gardens and fish-ponds, and the delices and ornaments of peace and tranquility?’

Though urged on by his peers and horticultural friends, Evelyn never completed the manuscript of ‘Elysium Britannicum’, a failure that is somewhat hard to explain, given that he managed to produce several books and various more modest pamphlets during his long career. It is also true that he left other works either unfinished (a ‘History of All Trades’) or unpublished (‘A History of Religion’).2 There is perhaps a cluster of explanations for why the gardening manuscript remained unpublished.

One, he could never finally master and then order the myriad details, the scientific and mechanical observations and researches that he had gathered and continued to accumulate during his lifetime through correspondence and personal contacts with many other virtuosi. Simply to look at almost any opening of the manuscript is to see how marginalia, pasted additions (some now unstuck), alternative ideas or words had accrued to augment, if not confuse, his arguments.3 Further, he found it hard to mesh some of these modern ideas with his wide readings in classical authors: his constant references to Varro, Columella, Palladius, Virgil and Cato seemed apt and still relevant, but they nonetheless smacked of an antiquarian relish that Francis Bacon, for example, would have suspected.

Two, the activity of compiling and ordering a huge book, not simple in itself, was complicated further by his public or civil service commitments after the Restoration and by the loss of some esteemed members of the Royal Society; struggling to put out a third edition of Sylva in 1679, he noted how so many ‘pillars’ of the Royal Society had been lost – notably Henry Oldenburg – taking away some of his philosophical and scientific colleagues upon whose communications he relied. In 1679 he also told Beale that he was much distracted by the Dutch wars and ‘three Executorships, besides other domestic concerns, either of them enough to distract a more steady and composed genius than mine’. He continued by noticing also ‘the public confusions in Church and Kingdom (never to be sufficiently deplored)’. His work as a Commissioner of the Privy Seal under James II made Robert Berkeley worry that this fresh activity would ‘hinder or divert you from finishing your grand design’, that is, ‘Elysium Britannicum’ (Evelyn DO, p. 127). Yet to Beale he added that ‘in all events you will see where my inclinations are fixed, and that love is stronger than death and secular affairs, which is the burial of all philosophical speculations and improvements.’ Nevertheless, he thought he might rescue a segment of his unfinished book titled ‘Of Sallets’ and issue it as ‘a complete volume’, Acetaria, but typically noted that it would need to be ‘accompanied with other accessories, according to my manner’.4 He did not know how to ‘take that Chapter out, and single it from the rest for the press, without some blemish to the rest’. In the end, he did exactly that in 1699, and also appended the outline of the troubled work that would no longer be published. Its abstract or synopsis is reproduced at the end of this chapter. Yet as it does not descend to particulars or arguments, it would not risk offending Evelyn’s deeply felt beliefs, which also played a role.

Reason three why ‘Elysium Britannicum’ remained unfinished and unpublished was that, as the comment to Beale implies, Evelyn did not remain ‘unconcerned’. He was unable to ignore any strong philosophical or religious objections to the discussion of natural materials that were at the heart of the ‘Elysium Britannicum’. That was clear earlier enough when he was reprimanded by Jeremy Taylor, whom he considered ‘my Ghostly Father’ in ‘spiritual matters’,5 about his villa at Sayes Court and his possessions there, to which Evelyn responded by apologizing for living in a ‘worldly manner near a great city’. Taylor had also wanted the book entitled ‘Paradise’, not ‘Elysium’, pulling Evelyn towards a more religious than antique position. Francis Harris has also argued that his worldly life and pride in house and garden became ‘a matter for confession and self-castigation’ in his later years.6 But while growing old may cause some retreat from the ‘gay things’, for which he apologized to Taylor even when a young man, that does not seem a sufficient block against putting together a book over which he had laboured so ardently from its inception. In 1679 he had written to Beale of

this fruitful and inexhaustible subject (I mean of horticulture) not fully yet digested to my mind, and what insuperable pains it will require to insert the (daily increasing) particulars into what I have already in some measure prepared, and which must of necessity be done by my own hand; I am almost out of hope, that I shall ever have strength and leisure to bring it to maturity, having for the last ten years of my life been in perpetual motion, and hardly two months in a year at my own habitation, or conversant with my family. (LB, II.632)

He excuses himself by appealing to the work he was required to perform for the king and his other political commitments, as well as his activity in the Royal Society and the pull of family time – all seem valid enough. Yet the ghostly presence of Jeremy Taylor (who had died in 1667) that lay behind his ‘excuses’, together with that strange remark to Beale that ‘my inclinations are fixed and . . . Love is stronger than Death’, suggest a deeper reluctance to tangle any more with writing a truly scientific treatise on horticulture; even if by ‘love’ he means his fondness for philosophical speculations, it is a reluctance he might also have felt less able to share with Beale, a fellow member of the Royal Society. And maybe, he was also nervous that a book subtitled ‘the Royal Garden’ consorted uncomfortably with the rise of Catholicism and the consequent removal of James II in 1688.

His reliance on Roman horticulturalists certainly offered often precise if not always relevant advice. But another more ‘modern’ and scientific figure like Lucretius was a less immediate help; he features at least nine times in the text, but in none of those references does Evelyn, in fact, dwell upon Epicurean atomism. Yet it seems to have been that Evelyn’s faith did collide with his increasing discomfort with Epicurean philosophy as espoused by Lucretius, and even with his wish to celebrate a royalist Elysium. So that ‘love’ or commitment reported to Beale disinclined him to complete the garden book, not least because he was too honest to fudge the contradictions involved.7

Evelyn had already begun his book on garden matters when in 1656 he published his translation of the first book of Lucretius’ De rerum natura, and several years before he circulated a draft of ‘Elysium Britannicum’ among fellow virtuosi. His Diary in 1656 noted that ‘Little of the Epicurean philosophy was then known among us’, thereby implying that it was part of his mission to translate another foreign and ancient work. If he had read, while still in France, the French prose translation of Lucretius’ De rerum natura by the Abbé de Morolles (1650), that was yet another incentive to take on this task of Englishing it. But what he published was only the first book of Lucretius, and his wavering on whether to go further suggested some real difficulty. When that volume appeared in 1656, he was supremely annoyed by the negligence of the printer who had so mangled his text that in his own copy he wrote that he was ‘discouraged . . . from troubling the world with the rest’ of the translation (Keynes, Bibliophily, p. 42). Authorial pique is one thing (nor was it the only time when he was annoyed with printing of his work); but a growing sense that what he was writing in the ‘Elysium’ was clearly contrary to his faith and conscience must have eaten away at his resolve to proceed. So maybe he could hide at least his own unease with further publishing by sheltering behind an annoyance with the printer.

Evelyn’s interest in Lucretius came before he was involved in the Royal Society’s ‘Georgical’ Committee (see Chapter Seven), but it clearly intrigued him by its concern with matters of nature, and that endorsed his discipleship of Bacon’s interest in exploring that world. Epicurus was known to have established his academy in a garden, which Evelyn’s friend Sir William Temple knew when later, in 1692, Temple entitled his own essay ‘On the Gardens of Epicurus’. As was argued earlier (see Chapter Six), some of the compliments that prefaced Evelyn’s translation of the first book of Lucretius were not entirely straightforward, at least to a man as fastidious as Evelyn, and they surely drew his attention to a disturbing new vision of the world, however much its physics appealed to men of the Royal Society. We have (in Michael Leslie’s words) ‘as antipathetic a conclusion as it is possible to imagine for a man of Evelyn’s stamp’.

Clearly, in his often muddled, uncertain and endlessly corrected text of ‘Elysium Britannicum’ he struggles with how to respond to its materials: he is happy to list Epicurus as a subject of garden statues among the statues of ‘moral and [famous] excellent’ figures, several of whom are listed (EB, p. 210), though he noticeably decided to delete the ‘excellent’ to describe him (shown here in the format that Ingram uses). But he is ill at ease with how to cope with Lucretius’ intrusions into his own arguments when in Chapter III of Book One, ‘Of the Principles and Elements in General’, he notes (in a somewhat complicated sentence) his ‘desire to reconcile whatsoever we may have spoken [my italics]’ with ‘the well restored doctrine of Epicurus; from which however, the notions seem [somewhat distinct &] hermetical and to interfere upon a superficial view, we neither do, nor intend to recede’ (EB, p. 40); again one notices his withdrawal from the ‘somewhat distinct’ to insisting on the hermetical world of Epicurean ideas. There is also the hesitant formulation of this ‘reconciliation’ – the corrections to his sentences – which reflect a constant unease with how he needed to explain himself. A marginal note, the date of which is of course unknown, reads: ‘My purpose was quite to alter the philosophical part of the first book’ (EB, p. 38). Yet after the remark about Epicurus cited above, when he writes that he will not ‘recede’, the manuscript continues with the simple phrase, ‘But to proceed’. But in the end he finds he cannot.

It is important to observe that soon after his translation of Book One of Lucretius was published, Evelyn started to compose ‘The History of Religions’, the title page of which notes that it was begun in 1657, and apparently (and interestingly) this ‘History’ was revised around 1683; it was first published in two Victorian editions of 1850 and 1859. The manuscript had been preserved at Wotton and was included by Evelyn among his projected works that he listed in ‘Memoires for my Grandson’; there he termed it a ‘larger book . . . being a congestion, hastily put into Chapters many years since, full of errors’ (my italics – a familiar refrain). The manuscript itself contains ‘a rough draft, a second copy, and marginal notes added during revision’.8 But as Keynes notes, its interest consists largely not in the historical narrative, but in Evelyn’s own observations in a short preface on the decay of religion, first under the Commonwealth, and later following the Restoration, when he was led to ‘examine for himself the grounds upon which his religious beliefs were founded’.

Religion, and particularly the version of Christianity embodied in the English state Church that emerged from the Reformation, had always been Evelyn’s bedrock. When he noted his careful observations of other forms of belief during his European travels, there was no wavering in his own faith, only a curiosity to observe other encounters and explorations. He had left England dismayed by the Presbyterians, survived the Interregnum’s repressions of the English liturgy and Church practice, and once the true faith as he saw it was restored, he maintained it steadfastly, above all in the following years when it was buffeted on all sides by Roman Catholicism, continuing Presbyterianism, and other forms of Dissent (‘I am neither Puritan, Presbyter, nor Independent,’ LB, I.88). So by the last years of the seventeenth century this particular version of Christianity was the one thing he would cling to, not least because he had very early found no ability or ‘ambitions to be a statesman, or meddle with the unlucky interests of kingdoms’ (EB, p. 469 note). And that became his idée fixe, a bulwark to be maintained against such modernisms as Hobbes’s materialism or Epicurus’ atomism, and one which survived as increasingly more important than the Baconian rigour he had espoused until it threatened his faith.

Leslie notes pertinently that while Bacon’s essay ‘Of Gardens’ began with ‘GOD Almighty first planted a garden’, after this conventional and rhetorical ‘flourish’ Bacon focused on the very practical details and didn’t mention God again. Evelyn by contrast begins two chapters of ‘Elysium Britannicum’ by invoking God as the ‘first gardener’, the memory of which ‘was not yet so far obliterated’ by those banished from its earthly paradise (EB, pp. 29, 330). Evelyn’s argument, as a devout member of the Church of England, is that he was determined to preserve his faith despite the challenge of rival creeds and new scientific ideas. Yet in the 1650s he had, one supposes, determined that he could still be a good English churchman and accept such modern ideas as those espoused in Epicureanism. Indeed, 1657 saw the publication of Walter Charleton’s The Immortality of the Human Soul Demonstrated by the Light of Nature, where Charleton makes Evelyn appear as ‘Lucretius’ to expound Epicurianism. Even as he was working on his Lucretius translation, there appeared a publication of Bacon’s juvenile writings that showed how much the younger man had espoused Epicurean and Lucretian ideas, a position that Bacon later worked hard to revoke. And eventually Evelyn himself found, as Leslie notes, that he would rather burn ‘all the poems in the world’ than allow that ‘anything of mine should contribute & minister to vice’.

The omnibus and encyclopaedic effort of ‘Elysium Britannicum’ would necessarily have included not only good science but a reverence for the natural and physical world that produced and sustained all horticulture. Other members of the Royal Society were less fraught over responding to new ideas and able to sustain their faith, like Nehemiah Grew or Richard Boyle. Grew’s work is cited in ‘Elysium Britannicum’ and his original lectures were delivered before the Royal Society, and indeed he thanked Evelyn when they were printed; but Grew’s attitude towards the natural world is that it is able to speak for itself, ‘without need of a God to cause plants to be the way they are’.9 One could observe and report on nature’s plants, or on the human bloodstream, without committing oneself to a faithlessness (such a delicate balance has, in fact, sustained many a good scientist in the long years since the seventeenth century). And, while it is palpably clear that Evelyn lost his Baconian edge as he progressed with ‘Elysium Britannicum’, it is also evident that the text itself, as it survives, does not present so dramatic a threat to faith. He may well have planned, as already noted, to ‘quite . . . alter’ the philosophical parts of the manuscript, but a close reading of it (though an extremely arduous task) does not confront a modern reader of the text with much sense that Evelyn was dismayed by what he left in the bulk of the manuscript. Most of his endless rewritings and hedging of emphases reveal a stylistic worrier and a conscientious horticulturalist as much as anxious piety, and his serious worries were left unwritten.

Another aspect of his uncertain attitude towards Lucretius concerns not only his work on the text of ‘Elysium Britannicum’, but what he might ‘contribute’ to actual gardens too. It has been argued that Lucretius and Epicurus found expression in Evelyn’s own garden designs.10 This seems hard to prove, and suppositions tend to fossilize into statements. R.W.F. Kroll sees that at Sayes Court Evelyn ‘express[ed] an Epicurean polity of friendship, though he does not attempt to explain this at the level of specific garden symbolism’. Precisely; it was indeed a place where he could welcome his friends, but friendship is not exclusively Lucretian or Epicurean. Nor is it easy to find adequate symbols in garden elements for that ‘polity’; even if it were possible, it would be expressed either in texts outside the garden itself or in calculated iconography within the design, which Evelyn avoids. A key idea of the garden as a respite from the busy world, expressing ‘tranquility of mind’ and ‘withdrawal from public affairs’ (A. and C. Smalls, p. 197), certainly emanates from Roman writings, but it was not exclusively Lucretian or Epicurean, and was readily and generally available in English culture during the seventeenth century. Though Evelyn himself envied Beale’s and Cowley’s escape ‘from noisy worlds, ambitious care and empty show’, he was incapable of following their example.

An extensive argument has been proposed that three gardens with which Evelyn was connected expressed themes of Epicurus: his brother’s garden at Wotton, his redesign of the terraces at Albury for Henry Howard, and his involvement with a younger Howard, Charles, at Deepdene, which Aubrey credits to Evelyn. In these three Surrey gardens, all designed, write the Smalls, ‘before 1660, several specific and quite explicit Epicurean motifs can be detected’ (p. 196). But it is not clear that Albury was designed before 1660, while he might have been still translating Lucretius (Evelyn went to Albury in 1667 and wrote that he had designed it, but with no mention of it having been projected much earlier). Similarly, George Evelyn certainly took advice from his younger brother, but it is unclear that Evelyn’s ‘programme’ (p. 200) for the site at Wotton involved explicit Epicurean ideas; even if it did, a statue of Venus as a goddess of gardens was a routine iconographical item, and to say that all the features that were originally there ‘formed part of John’s overall plan’ (p. 201) implies an art-historical rigour that would have been uncharacteristic of him.

Evelyn’s use of ancient ideas and themes in his garden designs was in fact eclectic (as the Smalls acknowledge), never precise or symbolic. The Smalls write that he was ‘never explicit about the symbolism of his garden designs’, but that ‘he gave a clear pointer’ when he wrote about Albury’s inspiration from his visit to Naples (p. 205). I am less sure that this is so ‘clear’. He was consciously thinking of his visit and says so explicitly in referring to the Neapolitan crypta as a Pausilippe; but it is implausible to think such an allusion or gesture involved him in constructing a whole programme – with a Roman bath (which may not be his anyway), a semicircular pool to represent the Lago di Agnano, the Albury gardens as the Elysian Fields which, in Italy, lay between Baiae and Misenum – and that all of that was explicitly Epicurean. And Evelyn’s design for Albury (see illus. 33) does not, or at least cannot, make such references clear on paper or in the garden itself.

On the other hand, the Smalls have an ingenious way of finding an Epicurean explanation of the experience of arriving on the Albury terraces through the tunnel under the hillside, as being analogous to the crypta in Naples: the optical illusion of emerging from the darkness into the light is discussed in De rerum natura, Book IV, and is partly quoted by Evelyn in Chapter X of Book II of ‘Elysium Britannicum’. But it hardly seems a Lucretian experience unique to Albury, as that section of his manuscript makes clear; even so, it presupposes that visitors would always arrive from the tunnel into the Albury gardens. In short, Evelyn may well have wished to espouse Lucretian ideas during the 1650s, but even in his own translation and presentation of them he was evasive and uncertain, as unwilling to publish as he was to articulate these ideas in garden forms and elements.

The résumé of ‘Elysium Britanicum’ that he circulated in 1660 and later appended to Acetaria does not correspond to the surviving manuscript that has now been transcribed by John Ingram, to which my references are given. As is clear, the synopsis is divided into three books, but much of Book II and all of III have been lost, with only portions, the Kalendarium Hortense and Acetaria, alone seeing publication. In the first book are general principles of the four elements,11 seasonal change, ‘celestial influences’, soils and their treatment, upon which basis any gardener has to work. The second book provides a very detailed review of what today we would call garden design and garden maintenance: from the requirements of a good gardener to the necessary skills of growing, planting and transplanting (with a calendar of monthly tasks), from a variety of pragmatic forms and requirements (fencing, upkeep, pests), to those garden elements that gave it beauty and ornament, and provide a spectacle for the eye and mind (‘Hortulan refreshments’). Yet for Evelyn the ornamental or ‘pleasure’ garden coexists with a cluster of other designed spaces that yield an abundance of useful items for the table and for medicine, and these he lists: conservatories, a vineyard, orchard, a vegetable garden or ‘olitorie’. The third book moves into a zone at once scientific and philosophical, cultural and social: here would be discussed a range of activities that clearly pertain to the making of a garden and its adjacent areas and concerns, like preserving and distilling, or he describes the representation of plants in paint or other materials, the creation of garlands, and the construction of a library of hortulan books. Beyond these, the third book opens out finally into a mare maggiore of themes – from entertainments in a garden to burials there, from gardens (including Paradise) to morals and a lex hortorum or ‘laws and privileges’ therein, and finally (as if the survey had been negligent in some fashion) to a history of ancient and modern gardens and a ‘Description of a Villa’.

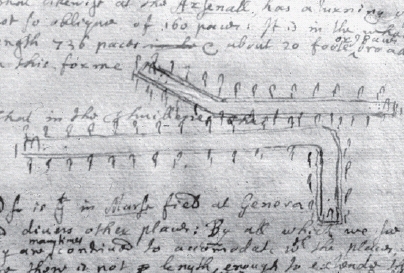

Throughout the manuscript that survives, the text is frequently augmented with diagrams, drawings and annexed explanations of such items as garden tools (illus. 40), perspectives, aviaries, rabbit warrens, beehives (see illus. 17), and of course plants and insects. The text, as transcribed by Ingram, is full of phrases or sentences crossed through, marginal notes added or pasted in, insertions of material too lengthy to be inserted in the text or written in the margins, some of which loose papers have become dislodged from their original location. It has to be said that Ingram’s printed text, with its careful recording of all these rewordings and rethinkings (second, third thoughts and so on), is infinitely more accessible to a reader than the actual manuscript. His edition uses modern typographical formats and annotations to present a semblance of the original manuscript which is nonetheless clear and hospitable. On the other hand, something is lost: the original manuscript allows a more authentic closeness to Evelyn’s instinctive and ever-changing response to his materials. Yet those authorial revisions, though persistent and endless, do not seem the real basis of Evelyn’s eventual difficulty with his book. To have accommodated them, absorbed them into his final draft, would be challenging but not impossible – it is a challenge that many authors have overcome.

40 Page from the ‘Elysium Britannicum’ showing garden tools, where no. 43 (at left towards the top) is a watering truck or barrel for the garden.

The whole seventeenth century was a time of upheavals, not only in politics and religion, with endless challenges to the stability of its population, but in concepts of knowledge and epistemology, with the sciences, especially physics, that underpinned them. If these were not enough for an intelligent and thoughtful, if traditional, man like Evelyn, there was a topic in which the ‘Elysium Britannicum’ was most involved, namely the making and use of gardens. Everything he had seen in Europe suggested new forms of design, new ways of using garden elements to signify or represent a conspectus of ideas that were not limited to the garden, even if embedded or given voice within them. Furthermore, it was clear to Evelyn that gardens, though still enabling the status of the rich and powerful, began to appeal to others – his time in the Netherlands, above all, made this democratization very clear. And then his own garden-making at Sayes Court sought to make some foreign ideas acceptable in ways that were clearly not apt for ‘royal gardens’, though that is the subtitle he gave to the ‘Elysium Britannicum’.

One of the difficulties he must have faced was that by the second half of the seventeenth century, garden forms and concepts were taken up and adjusted for a variety of different people and social conditions, in books like John Woolridge’s Systema Horti-culturae: or, the Art of Gardening (1677), Timothy Nourse’s Campania Foelix: or, A Discourse of the Benefits and Improvement of Husbandry (1700), and Nehemiah Grew’s Anatomy of Plants with an Idea of a Philosophical History of Plants (1682). Nor was ‘Elysium Britannicum’ likely to be a ‘universal’ work on the subject, as he told Beale, applicable to all; that Evelyn would not live to see books on clergymen’s or ladies’ gardening, issued by John Lawrence in 1714 and Lawrence again (writing curiously under the pseudonym of ‘Charles Evelyn’) in 1717, did not mean that these cultural and social changes were not apparent before being announced and published. And the topic of a universal treatise on gardens and garden-making would have been directed obviously to a wider readership in an age of much enlarged literacy and publishing, but also in an age with a wider range of believers, some of whom reverenced gardens but not an English faith, which was another anxiety to overcome.

Though it is hard to show in short space, some examples will serve to illustrate what Evelyn was struggling with, for it should be remembered that the impulse to write the ‘Elysium Britannicum’ was to make available in England and in the English language the wealth of gardening advices and information that its author had garnered in his travels and from his scrutiny of both ancient writings and contemporary learning. Two major issues confronted Evelyn when composing it: how to interpret ancient writings and relate them to modern practice – this was both semantically and horticulturally necessary; then, how to relate verbal, especially ancient, descriptions to modern visual imagery (on the assumption that his sketches in the manuscript could be adequately engraved, which is what Needham and his signatories were concerned to accomplish).

The first chapter of the first book addresses the first of these issues. Its three and a half pages in manuscript (four in Ingram’s transcription) are awash with Greek and Latin phrases, the glossing of which is obsessive, despite his remark that this ‘may pass for a conceit of the etymologist’. But the adjudication of ancient languages (a minimum of twelve classical authorities are cited) is but a step toward understanding what the terms mean in the modern world. There is little sense, in his universal tour d’horizon of gardens, that there is any cultural or social difference between God’s original Paradise, Adam’s postlapsarian need to ‘improve the fruits of the earth’, the Roman Horace, or the modern makers of the ‘four or five’ sorts of garden. To ‘define a garden now’ (my italics) is to subsume it into ‘a type of Heaven’, which is what worthy and illustrious kings, philosophers and wise men mean when they ‘describe a garden, and call it Elysium’, hence not one specifically adjusted to cultural locality. Evelyn’s need to secure the roots of his discussions in etymological research hampers his presentation of the material in modern times and terms, and one wonders how much his contemporaries needed to share his endless anxiety with origins. Indeed, much later (EB, p. 410), when he appeals to the ‘curious reader’ and promises to report on ‘wonderous and stupendious plants’, he asserts that he wishes to explain them ‘not in lofty words, but plain & veritable narrations, & in such language as will become [that is, suit] both our [modern] wonder and astonishment’. That emphasis, reminiscent of Sprat’s call for plainness of speech, is not compatible with the style of the opening chapters.

It comes, however, at precisely the point where he concludes his chapter on ‘the Philosophical-Medical Garden’ by sketching a garden of simples based on what he had seen in Paris (see illus. 9, 10). This representation ‘in perspective’, he explains, will clarify the many species of plants ‘for the most part strangers to our Elysium as yet’. It may be that Evelyn, unable to abandon his beloved etymology and verbal classicism, seeks to achieve something more direct and practical through images. The dialogue, or paragone (contest) if you will, between word and image, is also between the image and the various versions of the word that it illustrates. This is intimately aligned with his similar need to explore a universal Elysium as well as a modern and practical garden culture. Now it is perfectly possible to generalize about garden-making, and we all do it. But there is also the required understanding that each garden is different on account of its formal design, its climate and soil, its planting, and the social needs it serves. Evelyn certainly realized that during the years in which he gardened at Sayes Court and while visiting a variety of gardens in England (some of these are recounted in Chapter Eleven). Other late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century garden books, noted above, equally made clear that different assumptions underlaid and promoted gardens for a range of social classes and uses, not least those close to the metropolis as opposed to those in more distant counties. That particular social understanding was not adequately registered in ‘Elysium Britannicum’, though he was surely aware of them. Even when he received Beale’s careful account of Backbury Hill, he shifts it into both an exemplum of an ancient British or maybe Roman garden and lauds it as ‘no phantastical Utopia, but a real place’ (EB, p. 97). Yet his version is truly utopian, and he removes from his text any suggestion of its actual location in Herefordshire and makes analogies between it and Mt Sinai, the Garden of Semiramis in Media, and Paradise. It is clear, writes Alessandro Scafi, that Paradise is a flexible site:

Just as many international frontiers were originally zones of transmontane communication rather than clear-cut lines of sharp division, so Paradise seems to constitute a permeable boundary zone, a place where human space and time mix with divine infinity and eternity. Seen this way, Paradise is itself a boundary.12

What does, however, become clear is that it is in Evelyn’s sketches, presumably intended for reworking by a competent engraver, that he addresses horticultural particulars in a true Royal Society spirit. The images concentrate frequently on issues of planting, grafting, transplanting and transporting of specimens, just as his text in Chapter XVI of Book II is extremely detailed on the scope and contents of flower gardens. A crude sketch of a ‘coronary garden’ is labelled and the text shows how even an accomplished gardener, ‘master & general of all this multitude’, must be helped by depicting its exact delineation, its contents listed (and relisted when changes were made), so that he ‘shall have an immediate survey of your whole garden, & know what is planted in every bed’. Other sketches treat of rabbit warrens, aviaries modelled after the Roman Varro’s verbal description (a pattern of birdcages still found today), beehives that are transparent (see illus. 17) and are vertical, or horizontal and segmented, furnaces to warm silkworms, seed troughs, and a conspectus of garden tools. For a demonstration of how to render an illusionary landscape on a blank wall, a perspectival device that he had admired in Europe and thought would enhance a small space, he instances a garden in Ripon, Yorkshire, where at the end of a closed walk a perspective is contrived by placing ‘a looking glass set so declining as to take in the sky, having a landskip painted under it, which made a wonderful effect’ (EB, p. 218).

One example of a European garden element that is both ‘healthful’ and ‘more frequented in foreign countries than our own’ was to convert walks into ‘palle mailles’, namely long, or sometimes bent, alleys with boards along their sides and iron hoops at the end where bowls were played. (Pepys records his first view of a ‘Pelemele’ in April 1661, and the word survives today in London’s Pall Mall, which was established on the site where James II would play.) Evelyn’s sketches two examples he had seen in Paris, at the Arsenal and the Tuileries (illus. 41); the text notes others in Tours and at Genoa, and in each case their forms are accommodated to the specific site. The text is an extremely detailed explanation of both their construction and the equipment used (the wood for the balls is French box; the mallet is ash, bound with leather). His final word, unsurprisingly, also concerns trees: some of these pall-malls have double or even triple ranges of ‘most lofty & shady trees’, designed for the ‘grace and magnificence of the walks and to refresh our active gamester’.

41 A sketch from the ‘Elysium Britannicum’ showing walks for ‘pell mell’.

The verbal descriptions make good sense of this conjunction of word and image, linking an example to its more conceptual and theoretical explanations. One section is especially intriguing as it addresses a matter that is usually evaded in garden discussions, namely sound.13 Moving water in gardens is an obvious auditory source, and Evelyn’s chapter IX of Book II takes on the provision and manipulation of waterworks of various kinds. But the following sequence, ‘Of artificial echoes, music’, explains how music can be made in a hydraulically operated cylinder, with a page of music appended (EB, 234–6), how water can imitate birdsong, and how water in hydraulically worked trumpets will sound the times of day; there is further, in a chapter on insects, music that will tempt a tarantula spider out of its ‘fits’ into an ‘amicable concert’, though should the musician make a discord, the spider will ‘grow mad again’!

Evelyn’s concern for a modern England was to marry garden use and practice with philosophical and imaginative resources. Central to this is his determination to bring into modern gardens the rich repertory of garden ornaments, which he lists as ‘caves, grots, mounts, and irregular ornaments’ that ‘do influence the soul and spirits of man’. That was a very contemporary design vocabulary, visible enough in Europe but rarer in most Elizabeth and Jacobean gardens. It allowed him to provide specific particulars while elaborating on the universality of garden experience. But the point of those features, as he constantly advised, was that gardens represent, via their various ingredients, a world that is outside and bigger than one single garden: he is endlessly concerned to underline that the collaboration of nature and art in garden-making was but a local and careful intimation or representation of larger cultural and primitive natures outside them. I have discussed these ideas at length in an earlier essay;14 I would, however, add that the point I was making in 1998 was perhaps too inclined to emphasize the efficiency of a universal theory in Evelyn than to see how his seventeenth-century context determined his theories. In the next century or so after Evelyn, notions of representation changed radically, yet gardens never lost the need or obligation to speak of things beyond themselves. That is why Evelyn’s is still a work that teaches how we should understand those connections; that he did not, could not, anticipate how things would in fact change, does not make him less important, but only allows us to see him carefully in and of his time.

OUTLINE OF ‘ELYSIUM BRITANNICUM’ (1699)

THE PLAN OF A ROYAL GARDEN:

Describing, and Shewing the Amplitude, and Extent of that Part of Georgicks, which belongs to Horticulture;

IN THREE BOOKS.

BOOK I.

Chap. I. Of Principles and Elements in general.

Ch. II. Of the Four (vulgarly reputed) Elements; Fire, Air, Water, Earth.

Ch. III. Of the Celestial Influences, and particularly of the Sun, Moon, and of the Climates.

Ch. IV. Of the Four Annual Seasons.

Ch. V. Of the Natural Mould and Soil of a Garden.

Ch. VI. Of Composts, and Stercoration, Repastination, Dressing and Stirring the Earth and Mould of a Garden.

BOOK II.

Chap. I. A Garden Deriv’d and Defin’d; its Dignity, Distinction, and Sorts.

Ch. II. Of a Gardiner, how to be qualify’d, regarded and rewarded; his Habitation, Cloathing, Diet, Under-Workmen and Assistants.

Ch. III. Of the Instruments belonging to a Gardiner; their various Uses, and Machanical Powers.

Ch. IV. Of the Terms us’d, and affected by Gardiners.

Ch. V. Of Enclosing, Fencing, Platting, and disposing of the Ground; and of Terraces, Walks, Allies, Malls, Bowling-Greens, &c.

Ch. VI. Of a Seminary, Nurseries; and of Propagating Trees, Plants and Flowers, Planting and Transplanting, &c.

Ch. VII. Of Knots, Parterres, Compartiments, Borders, Banks and Embossments.

Ch. VIII. Of Groves, Labyrinths, Dedals, Cabinets, Cradles, Close-Walks, Galleries, Pavilions, Portico’s, Lanterns, and other Relievo’s; of Topiary and Hortulan Architecture.

Ch. IX. Of Fountains, Jetto’s, Cascades, Rivulets, Piscina’s, Canals, Baths, and other Natural, and Artificial Water-works.

Ch. X. Of Rocks, Grotts, Cryptae, Mounts, Precipices, Ventiducts, Conservatories, of Ice and Snow, and other Hortulan Refreshments.

Ch. XI. Of Statues, Busts, Obelisks, Columns, Inscriptions, Dials, Vasa’s, Perspectives, Paintings, and other Ornaments.

Ch. XII. Of Gazon-Theatres, Amphitheatres, Artificial Echo’s, Automata and Hydraulic Musick.

Ch. XIII. Of Aviaries, Apiaries, Vivaries, Insects, &c.

Ch. XIV. Of Verdures, Perennial Greens, and Perpetual Springs.

Ch. XV. Of Orangeries, Oporotheca’s, Hybernacula, Stoves, and Conservatories of Tender Plants and Fruits, and how to order them.

Ch. XVI. Of the Coronary Garden: Flowers and Rare Plants, how they are to be Raised, Governed and Improved; and how the Gardiner is to keep his Register.

Ch. XVII. Of the Philosophical Medical Garden.

Ch. XVIII. Of Stupendous and Wonderful Plants.

Ch. XIX. Of the Hort-Yard and Potagere; and what Fruit-Trees, Olitory and Esculent Plants, may be admitted into a Garden of Pleasure.

Ch. XX. Of Sallets.

Ch. XXI. Of a Vineyard, and Directions concerning the making of Wine and other Vinous Liquors, and of Teas.

Ch. XXII. Of Watering, Pruning, Plashing, Pallisading, Nailing, Clipping, Mowing, Rawling, Weeding, Cleansing, &c.

Ch. XXIII. Of the Enemies and Infirmities to which Gardens are obnoxious, together with the Remedies.

Ch. XXIV. Of the Gardiner’s Almanack or Kalendarium Hortense, directing what he is to do Monthly, and what Fruits and Flowers are in prime.

BOOK III.

Ch. I. Of Conserving, Properating, Retarding, Multiplying, Transmuting and Altering the Species, Forms, and (reputed) Substantial Qualities of Plants, Fruits and Flowers.

Ch. II. Of the Hortulan Elaboratory; and of distilling and extracting of Waters, Spirits, Essences, Salts, Colours, Resuscitation of Plants, with other rare Experiments, and an Account of their Virtues.

Ch. III. Of Composing the Hortus Hyemalis, and making Books, of Natural, Arid Plants and Flowers, with several Ways of Preserving them in their Beauty.

Ch. IV. Of Painting of Flowers, Flowers enamell’d, Silk, Callico’s, Paper, Wax, Guns, Pasts, Horns, Glass, Shells, Feathers, Moss, Pietra Comessa, Inlayings, Embroyderies, Carvings, and other Artificial Representations of them.

Ch. V. Of Crowns, Chaplets, Garlands, Festoons, Encarpa, Flower-Pots, Nosegays, Poesies, Deckings, and other Flowery Pomps.

Ch. VI. Of Hortulan Laws and Privileges.

Ch. VII. Of the Hortulan Study, and of a Library, Authors and Books assistant to it.

Ch. VIII. Of Hortulan Entertainments, Natural, Divine, Moral, and Political; with divers Historical Passages, and Solemnities, to shew the Riches, Beauty, Wonder, Plenty, Delight, and Universal Use of Gardens.

Ch. IX. Of Garden Burial.

Ch. X. Of Paradise, and of the most Famous Gardens in the World; Ancient and Modern. Ch. xi. The Description of a Villa.

Ch. XII. The Corollary and Conclusion.

Laudato ingentia rura,

Exiguum colito.

That dialogue or balance of these two competing instincts in garden-making – the particular and conceptual, the local and the general – is hard to adjudicate, probably unnecessary. My sense now is that it is with particulars that Evelyn makes his best case, and that it did not depend upon ancient lore or authority, though he loved to think it did. In 1998 when I first wrote about the ‘Elysium’, I wanted to find in it an idea or theory that held general application; Evelyn himself asks for an ‘incomparable use’ of his ideas to be a ‘fit at all seasons’ (EB, p. 134, though he was writing specifically of garden walks). His was not, as he told Beale, a ‘steady & composed genius’, and his work remains fragmentary and palimpsestic. But his genius still grasped some of the ineluctable truths of garden-making and articulated their worth for England. That he could not shape them into a coherent whole and that his countrymen never got to read it before their gardens were taken over by the furor of so-called English landscaping in the eighteenth century is an unhappy trick of history.