Both morphologically and behaviourally, the cheetah is one of the most specialised cats. It is the only species that hunts by means of a prolonged, high-velocity chase and no other living felid displays the suite of adaptations that afford the cheetah its extraordinary speed. To see a cheetah in full flight suggests the cat family at its most successful; but, in fact, evolution has given rise to sprinting cats on only a handful of occasions. Relative newcomers to the felid family tree, the pursuit cats briefly enjoyed a distribution that spanned the globe. Today, they are all extinct except for the modern cheetah.

All cats are carnivores, which means, of course, that they eat meat. Indeed, except for skin, fur, bone and emetic meals of grass, most cats eat little else. Consequently, all cats exhibit adaptations for hyper-carnivory, that is, a diet made up exclusively (or almost exclusively) of meat.

Before we discuss those adaptations, the term ‘carnivore’ needs to be clarified. Cats are members of the order Carnivora, a group of related mammals that also includes hyaenas, dogs, bears, mongooses, genets, raccoons and weasels. Seals and sea lions also belong to the Carnivora though they are occasionally accorded their own order. Including seals, there are 264 modern species within the Carnivora, all united by a shared descent and a diet dominated by meat. Informally, they are known as carnivores, though some species such as bears and raccoons are actually omnivorous and a handful feed on plants alone; giant pandas eat mainly bamboo. Equally, any species that eats meat – such as humans – can be described as a carnivore but that does not make it a member of the order Carnivora. As used throughout this book and in biological discussions in general, the carnivores are those species that belong to the order Carnivora.

CLASSIFICATION OF THE CHEETAH

Every species known to science is classified according to a tiered system that groups related species together. The higher the tier, the more distant the relationship. For example, all animals, everything from cheetahs to jellyfishes, belong to the same kingdom, Animalia. Those animals that possess a notochord (which gives rise to the spine or an equivalent structure) are grouped in the next category, the phylum Chordata, an assemblage that includes cheetahs but excludes jellyfishes. The phylum Chordata is made up of many classes, one of which is Mammalia, the mammals, which are united in possessing hair and mammary glands to suckle their young. The mammals are further sub-divided into orders – for example, Carnivora for cheetahs and all other carnivores – each of which contains a number of families: all cats belong to the Felidae, dogs to the Canidae, and so on. Within each family, closely related species share the same genus, but every species has its own specific name. Various sub-categories may be applied within each level but the essentials of the cheetah’s taxonomy look like this*:

| Kingdom | Animalia |

| Phylum | Chordata |

| Class | Mammalia |

| Order | Carnivora |

| Family | Felidae |

| Genus | Acinonyx |

| Species | Jubatus |

* sub-species of cheetahs are discussed in Chapter 6, see page 124.

The dates for the divergence of the different felid lineages are approximate. Current molecular and fossil data is often very contradictory on this point and accurate dating is yet to be achieved for most feline lineages.

A gallery of modern members of the order Carnivora. Clockwise from top left: spotted hyaenas, lion, dwarf mongoose, Cape fur seal and serval. All of them eat meat and all share key molecular and morphological characteristics that group them together as carnivores.

The earliest carnivores, the miacids, probably looked and behaved much like this large-spotted genet from Africa. Miacids gave rise to all modern carnivores which makes them the cheetah’s earliest ancestor that is easily distinguishable.

The earliest members of the Carnivora made their first appearance around 60 million years ago. Compared to the spectacular species that came later, they were rather unremarkable. Called miacids, these ancestral carnivores were small-bodied tree-dwellers that resembled modern-day genets in their morphology, and most likely in behaviour as well. Small and nimble with elongated, flexible spines and long tails, the miacids prospered in the dense forests that dominated their world. They had small brains and like today’s genets, probably pursued an essentially solitary lifestyle as adults, with the female shouldering all the parental duties. Their claws were retractile, providing proficiency during arboreal hunts though as in modern genets, they probably also foraged on the ground. Miacids were generalist predators; they hunted small prey like invertebrates, lizards, birds and small mammals, but they were also able to deal with eggs, fruit, nectar and seeds.

The miacids are ancestral to all modern-day carnivores. Early in their evolution, a profound split among the miacids set up the division manifested in today’s Carnivora as two major sub-orders: the Feliformia made up of cat-like families, and the Caniformia comprising dog-like families. One sub-group of the miacids called the vulpavines (‘fox-like forms’) was the ancestor group of the caniform carnivores: dogs, bears, seals, raccoons and weasels. Also included in this branch is a now extinct family known as the bear-dogs or half-dogs (Amphicyonidae). Appropriately named, the bear-dogs looked like large, heavy-set dogs with powerful bear-like front limbs and finer, dog-like hindquarters ending in a long tail. The largest species was the size of a modern grizzly bear. The bear-dogs existed until around six million years ago.

The other miacid sub-group, the viverravines, gave rise to the feliform families: cats, hyaenas, genets and mongooses. As in the Caniformia, the Feliformia also have an extinct family in their evolutionary closet – the Nimravidae. Known as the palaeofelids or nimravid cats, the Nimravidae were remarkably feline, so that if one appeared today, only a specialist in fossil carnivores would recognise it for something other than a cat. Indeed, the nimravids were formerly classified within the cat family, but enough differences have since been discovered to assign them their own family. The nimravids appeared before the true cats and existed alongside them for around 25 million years before the last representatives of the family died out towards the end of the Miocene period (see diagram on page 29) about seven million years ago.

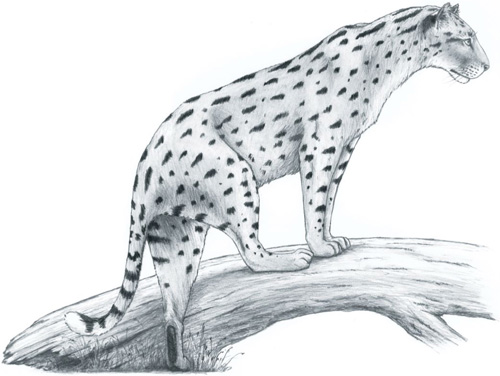

The nimravids ranged from housecat-sized forms to a species that was as large as a modern brown bear. Like cats, they were hyper-carnivores. Indeed, although the cat family is widely associated with extreme elongation of the upper canines into ‘sabres’ (discussed in the next section, see pages 33–34), the nimravids took the sabre-toothed specialisation to its evolutionary pinnacle. Sabre-teeth appeared in a succession of nimravids ranging from a housecat-sized species with two-inch sabres up to Barbourofelis, a lion-sized species whose massive canines rested against a scabbard-like bony flange on the lower jaw when the mouth was closed.

Intriguingly, the nimravids may also have been the first group to experiment with a sprinting, cheetah-like species. Alongside the family’s many sabre-toothed members, a second nimravid lineage arose, comprising a handful of species that had canines similar to the ‘normal’ conical shape in today’s true cats. Within this branch, a species called Dinaelurus appeared around 30 million years ago. Dinaelurus has not left behind much in the way of fossils; in fact, all we know of the species is a single skull, but it shows a striking resemblance to the cheetah’s – highly domed with a fore-shortened face, large nasal cavities and small canines (the reasons for which in the modern cheetah are explained later in this chapter, see pages 40–41). In contrast to other nimravids, which were mostly heavy-weight ambush hunters, Dinaelurus may have been a sort of proto-cheetah that relied on high speed to secure its prey. Unless more fossil material is unearthed, we may never know for sure; regardless, it is important to remember that Dinaelurus was a nimravid, not a cat. Dinaelurus was not ancestral to the cheetah or to any cat, and had died out many millions of years before the true felids rose to ascendancy. It would be another 20 million years before the first true cheetahs appeared.

PURRERS AND ROARERS

Modern molecular and fossil evidence demonstrates persuasively that the cheetah is not closely related to the big cats – lion, tiger, leopard and jaguar, collectively making up the genus Panthera. Yet even before recent scientific advances, cheetahs were never considered one of the group. Historically, the big cats were only those able to roar, while all others were grouped together as ‘purrers’.

Among cats, the hyoid – a delicate, bony sling in the throat, which supports the larynx and tongue – is either entirely bone or it has an elastic ligament. Only the big cats have the ligament, long held to be the reason they can roar because it enables them to expand the throat to lower pitch and increase resonance. It is also thought to be why big cats cannot purr continually; they are able to purr only when exhaling whereas all other cats (including the cheetah) can maintain the purr when taking a breath.

However, it is not quite that clear-cut. The snow leopard from Central Asia also has a short elastic ligament in its hyoid but has never been heard to roar; even so, molecular analyses link it closely to the big cats. Similarly, some authorities place the clouded leopard on the big cat branch, though it also never roars. Both species can purr continuously. Recent research suggests that large, fibrous pads on the vocal folds are actually responsible for roaring in the Panthera cats. The research is ongoing.

The early cat, Proailurus, showing the semi-plantigrade stance that was probably utilised for stability while climbing. As depicted here, the pad on the hind foot may have extended along the entire length of the foot, a feature seen in numerous semi-plantigrade carnivores today.

(© Luke Hunter)

THE FELINE PROLIFERATION

The earliest known felids appeared on the scene around 30 million years ago in what is now Europe. The point at which the first cats arose from their miacid ancestors is, of course, not a single moment in time (see box ‘Natural selection and fossil species’ on page 38). Over millennia, one branch of miacids became progressively more cat-like until, during the late Oligocene, we have a species that is recognisably a felid. Its name is Proailurus, meaning ‘early cat’. Proailurus was a robust, ocelot-sized cat that retained many of the primitive (meaning ancestral but not necessarily inferior) characteristics of its miacid ancestors. Most tellingly, it had more teeth than any modern cats. In the move towards a purely meat-eating way of life – hyper-carnivory – modern cats have lost most of their rear crushing molars, whereas caniform carnivores still have these molars to deal with bones. The cheek teeth, or carnassials, which felids have retained, have become specialised meat-slicers and look like flattened blades that slide closely past each other in a scissor-like action as the jaw closes. Proailurus also had such carnassials and was certainly a strict meat-eater, but unlike modern cats it also had the rear molars.

Although cheetahs are unique among felids for numerous reasons (see text), this cheetah skull shows the well developed canines and reduced number of cheek teeth typical of all modern cats.

Proailurus also resembled the miacids in its many arboreal adaptations. It had a supple, elongated back, as well as highly flexible ankles and – in contrast to all modern cats – a semi-plantigrade stance. Plantigrade species like bears and humans stand on the heel, whereas modern cats are digitigrade, or toe-standers. The overall effect in Proailurus was an animal probably very similar in appearance and lifestyle to the fossa of Madagascar. Uncannily feline in appearance but actually related to civets and genets, the fossa hunts lemurs in the canopy with extraordinary agility. Proailurus probably did likewise, targeting primitive primates, early squirrels and birds.

The fossa, probably the closest modern analogue of the early cat Proailurus. At almost 2 metres from nose to tail, with semi-retractile claws and a dentition for hyper-carnivory, the fossa fills Madagascar’s ‘big cat’ niche. Indeed, up until quite recently, it was considered a member of the Felidae family.

Fossils of the early cats are extremely rare and there are large gaps in Proailurus’ family tree until about 20 million years ago. At this time, a new genus of cats called Pseudaelurus appeared, probably a direct descendant of Proailurus. Pseudaelurus had lost some of its progenitors’ more primitive traits and, except for being slightly less digitigrade, is barely distinguishable from today’s cats. The emergence of Pseudaelurus marks a turning point in the evolution of the cats. Whereas much of the world was cloaked in humid, dense forests during the time of Proailurus, the world was becoming cooler and drier during the late Oligocene and early Miocene. The result was the spread of open savannah and grasslands and an explosion of grazers and seed-eaters that arose to inhabit them. As the niches available to predators proliferated, Pseudaelurus diversified to exploit them. While some Pseudaelurus species hung on to an arboreal lifestyle, others became more terrestrial and more cursorial (meaning ‘running’). They also grew larger and this is the first time that cats reached 30 kilograms, about the weight of a young adult cheetah. Pseudaelurus spread rapidly across its ancestral home of Eurasia and, during the early Miocene, entered Africa across a land bridge that appeared as ocean levels dropped in the cool, dry conditions. For the first time in its history, Africa was home to cats.

By the middle of the Miocene, Pseudaelurus was a genus with a number of species scattered around the world. Some species survived unchanged until about eight million years ago, but others gave rise to all the lineages of cats alive today – and some extinct ones. An estimated 15 million years ago, Pseudaelurus began to follow two distinct evolutionary paths. One led to modern cats (discussed below, see pages 34–37) while the other gave rise to the famous sabre-tooths. Erroneously called tigers (they are not closely related to tigers – a modern domestic cat is more closely related to tigers than any sabre-tooth), the sabre-tooth branch diversified into a wealth of spectacular species. The best known is Smilodon fatalis, the California sabre-tooth; thousands of fossils representing an estimated 1 200 individuals have been recovered from California’s La Brea tar pits. Smilodon occurred in North and South America and survived until extremely recently; the youngest fossils are only 9 500 years old, making them the most recent survivors of the sabre-tooth branch.

The sabre-tooths, Smilodon (left) and its likely progenitor, Megantereon (right). Megantereon is one of the few sabre-toothed cats that had a sheath-like flange on the mandible. The feature appeared in other sabre-toothed carnivores (including the nimravids, where it was widespread) but its exact function is unclear; it may have helped protect the hugely enlarged canines from damage.

Note: reconstructions are not to scale. Smilodon was considerably larger than Megantereon.

(© Luke Hunter)

The sabre-tooths also had African representatives such as Megantereon, a powerfully built species the size of a large, very robust leopard. Megantereon and other African sabre-tooths died out much earlier than the American sabre-tooths, but even so they lived for two million years alongside modern African cats. If we could glimpse an African scene from three million years ago, we would see at least three species of large sabre-tooths occupying the same range of habitats as lions, leopards and cheetahs. Megantereon probably chased cheetahs off their kills just as lions and leopards do today.

All living cats, including the cheetah, descend from the second Pseudaelurus branch. Often called conical-toothed cats to distinguish them from the sabre-tooths, they radiated into a number of different lineages, beginning many millions of years after the sabre-tooths diverged on their own offshoot. The phylogeny (evolutionary relationships) of the conical-toothed cats is still hotly debated but today’s 36 species of felids are thought to be clustered into eight major groups (illustrated in the diagram on page 29). Most of the relationships are beyond the scope of this book, but of course the interesting question is: where does the cheetah fit in?

THE ARRIVAL OF THE CHEETAH

By 3.5 to 3.0 million years ago, the modern cheetah Acinonyx jubatus was a well established species. The global trend of gradual cooling which had kick-started the great radiation of the cats in Pseudaelurus had been gathering speed through the Miocene and into the Pliocene, when cheetahs first appeared. As it had for Pseudaelurus, the opening up of closed habitats favoured an increasingly cursorial lifestyle, one which cheetahs exploited to its evolutionary climax.

The oldest cheetah fossils are from East Africa (with slightly younger ones from Southern Africa) and it is generally thought that cheetahs had an African genesis then spread through Eurasia. However, there are two stumbling blocks with this theory. The first is the lack of fossils that could represent cheetah ancestors. Cheetahs make a rather sudden appearance in the fossil record around the globe at almost the same time; there are no fossil links to their Pseudaelurus progenitors that might reveal where – and when – cheetahs first arose.

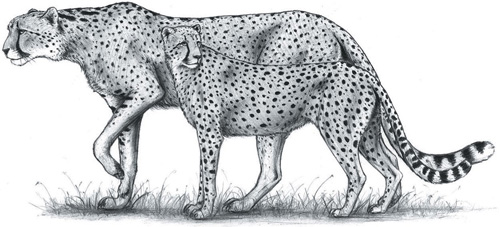

The giant European cheetah Acinonyx pardinensis depicted against a modern cheetah to illustrate the size difference. Although the height of a lioness, the giant cheetah was considerably leaner and the largest males would have weighed around 100–105 kilograms.

(© Luke Hunter)

The second problem is that the modern cheetah was not alone. At essentially the date we first see the cheetah, other different cheetah species were popping up around the world. Easily the most impressive was Acinonyx pardinensis, the giant European cheetah (also called the Villafranchian cheetah, named after the location in Italy in which it first appeared). At around the size of a lean lioness, the European cheetah was much larger than any cheetah today and weighed almost twice as much. Yet its proportions, particularly those of its limbs, are virtually identical to the modern cheetah and it was certainly as specialised a sprinter. Having long legs translates to a greater stride length, one of the means by which cheetahs attain such high speeds (see page 38) and it has been suggested that the taller European cheetah was faster than the modern form. However, heavier animals have more robust spines to support their greater weight and this might have counteracted any advantage; a flexible spine also enhances stride length so the slightly stiffer European cheetah might have been out-gunned in a race with its smaller, more supple cousin. Regardless, the European cheetah was certainly very fast and must have been an extraordinary sight running down the large antelopes and deer of Pleistocene Eurasia. The last records we have of this remarkable species date to about 500 000 years ago.

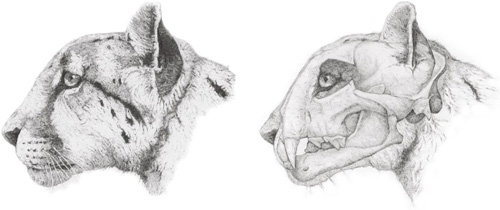

The north American cheetah, Miracinonyx. In the reconstruction of the animal’s head in life (left), Miracinonyx clearly resembled the modern cheetah. Among the many features it shared with the cheetah, Miracinonyx had a lightweight, domed skull with a short face, reduced canines and enlarged nasal cavities, shown in the cutaway on the right.

(© Neil Taylor)

At exactly the time the European cheetah first appeared on the Eurasian steppes, another giant cheetah-like cat emerged on the other side of the world. Known only from North America, a genus of sprinting cats called Miracinonyx arose about 3.2 million years ago. At an estimated 95 kilograms, the earliest species, Miracinonyx inexpectus, was only slightly smaller than the European cheetah while a later form, M. trumani, was about the same size as the modern cheetah. Both species shared the same elongate, slender limb bones and the small, domed skull seen in cheetahs. However, Miracinonyx differed from cheetahs in a few fundamental ways. Foremost among them was their ability to retract their claws. Miracinonyx retained the fully retractile claws of their Pseudaelurus forebears, an ability which has deteriorated in cheetahs (see page 39). Together with a handful of other skeletal discrepancies, this seems to argue against a close relationship with cheetahs, suggesting instead that Miracinonyx is more closely allied with other cats. Indeed, a long list of skeletal features and its geographic range indicate that Miracinonyx is closely related to the puma of North, Central and South America.

At this point, the story of the cheetah’s ancestry becomes intriguing. Recent molecular analyses group the cheetah with the puma. Cheetahs, pumas and a small Latin American cat called the jaguarundi share very similar sequences in some key mitochondrial genes known among carnivores for their high rates of mutation. The fact that cheetahs, pumas and jaguarundis have retained the same sequences is a compelling argument for a common heritage. When subsequent research expanded upon the molecular data and scored the cat family across a broad range of characteristics that included features of the skulls and the appearance of the chromosomes, the same grouping presented itself. It suggests that cheetahs and pumas, as well as jaguarundis, are descended from a common ancestor that diverged from the feline family tree to follow its own distinct evolutionary path many millions of years ago. Sitting comfortably on that branch, Miracinonyx could easily be a cheetah-like puma or a puma-like cheetah. In fact, Miracinonyx possibly holds the key to the cheetah’s earliest origins. That Miracinonyx retains the more ancient condition of fully retractile claws may argue that it – or a form like it – preceded the African and Eurasian cheetahs. If so, then cheetahs may actually have originated in North America and subsequently spread into Eurasia and Africa.

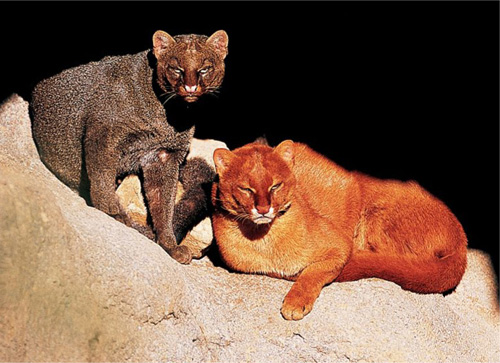

The probable closest living relatives of the cheetah, the jaguarundi (top, showing two common colour phases) and the puma. Both species are restricted to the Americas which, to some evolutionary biologists, contributes to the argument for an American origin of the cheetah.

Even if this is true, it does not necessarily make the modern cheetah’s origins anything other than African. The cheetah as we know it may have first evolved in Africa (as the fossils suggest) from an earlier species on the cheetah-puma branch which had arisen elsewhere and colonised Africa. Then, shortly after its appearance in Africa 3.5 million years ago, the modern cheetah could have spread rapidly throughout Eurasia while other cheetah species were evolving elsewhere in the world, possibly from the same distant ancestor that gave rise to the African cheetah. Clearly, there are still great gaps in our knowledge of the cheetah’s evolution. Unless earlier members of the cheetah-puma branch give up their fossils, these may never be resolved.

NATURAL SELECTION AND FOSSIL SPECIES

Natural selection acts upon the variation that occurs naturally within every species, favouring those characteristics that are better suited to survival. For example, imagine a population of proto-cheetahs with a range of leg lengths surviving on fleet-of-foot antelopes. As longer legs are better for running down speedy prey, those proto-cheetah individuals with slightly longer legs have a selective advantage. They are more likely to survive and pass on their legginess to their offspring so that over hundreds of generations the proto-cheetahs become longer in the leg. Those individuals with short legs either die out or, if suitable ecological opportunities such as slower prey are available, diversify into a different form that does not rely on speed. In theory, both forms could be equally successful, in which case two different species would ultimately emerge from the proto-cheetah population. Speciation is a process that takes place very gradually over millennia and complicates the job of palaeontologists describing extinct species; when is one form different enough to an earlier one to be deemed a separate species? In effect, our classification of all organisms as species is an instantaneous and somewhat artificial snapshot on the evolutionary process. Given another few million years of natural selection, today’s cheetahs might be an entirely different species.

THE MODERN CHEETAH: FORM AND FUNCTION

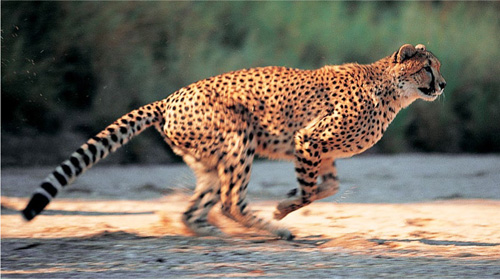

Whatever its origins, the modern cheetah is the fastest mammal on earth. Indeed, except perhaps for its extinct European cousin, it is probably the fastest terrestrial mammal that has ever lived. Exactly how fast is still unknown. The most accurate measurement to date puts the speed at 105 km/h but this is almost certainly not the upper limit. A two-year-old captive female timed with a laser gun was clocked at 99 km/h but, as an adolescent, she would not have reached her maximum potential and, in any case, was apparently coasting during the trials! Cheetahs can probably hit 110 to 115 km/h at least briefly during the chase, but their absolute best remains to be seen.

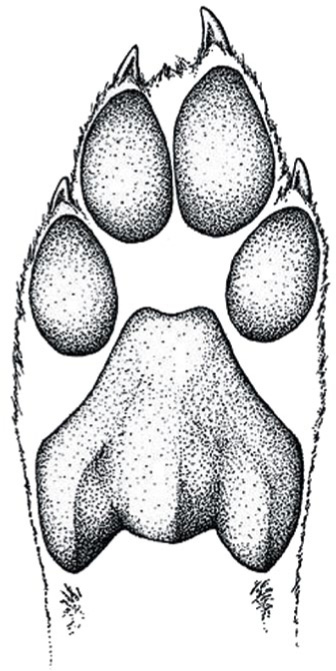

The cheetah’s hind paw: blunt, dog-like claws and the ridged plantar pad facilitate a firm grip at high speeds and also contribute to the cheetah’s explosive acceleration. In the first two seconds of the sprint, it will pass the 75 km/h mark.

(Paw illustration: © Luke Hunter)

To achieve their breath-taking velocities, cheetahs have to overcome two basic biomechanical challenges: they must be able to maximise the distance covered in each stride (stride length); and they must be able to increase the tempo at which they can take a stride (stride rate). To meet these requirements, evolution has equipped the cheetah with some highly specialised modifications to the basic cat form. Its lightly built legs are the most elongated of any large cat and indeed the cheetah is the only cat in which the relative lengths of the radius in the ‘forearm’ and the humerus (‘upper arm’) are virtually identical; in powerfully built heavyweights that rely on enormous strength rather than speed, the lower limb bones are proportionally shorter. Longer legs, of course, furnish the cheetah with a longer stride. Cheetahs further augment their stride length with a spine that is proportionally the longest and most flexible of any large cat. A biologist with a fascination for the slightly morbid once calculated that a legless cheetah could reach a speed of 15 km/h just by the bunching and uncoiling action of the spine. Combining legs and spine, the effect in the cheetah is a stride that measures just under ten meters at top speed. For more than half of every stride, the cheetah is completely airborne.

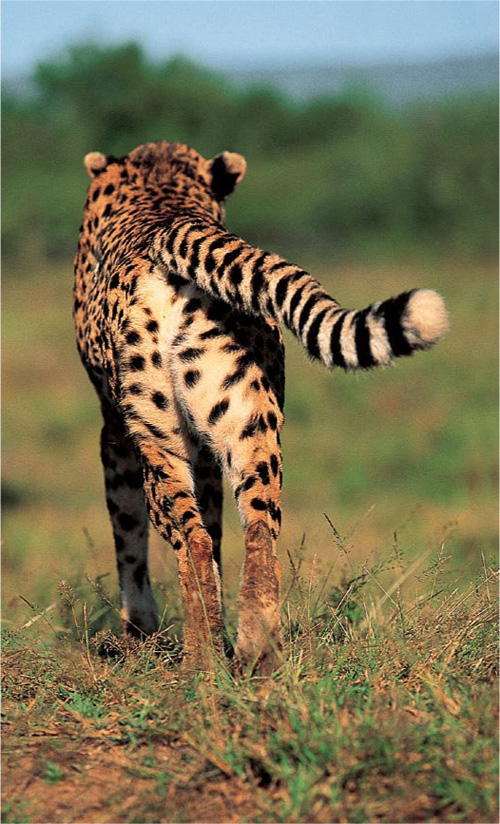

Most of the cheetah’s propulsive force is generated by the strongly muscled hind legs. The front legs and long, tubular tail work together to achieve lightning-fast changes in direction.

To boost their stride rate, cheetahs have lightweight legs. The advantages of a tremendous stride length would be counteracted if the cheetah had to heft bulky paws with every step, so the bones of the lower legs and paws are slender and light. Moreover, the muscles that do most of the work are bunched high on each leg, close to the body; long, light ligaments transfer the muscular action down the limb without the need for dense, heavy muscles on the lower leg. The result for a cheetah running at 93 km/h is an astonishing three and a half strides every second. To ensure stability and strength at such speeds, fibrous ligaments tightly bind the fine bones of the lower leg in a rigid unit. This restricts the amount of rotation in the lower limb, crucial for resisting the phenomenal stresses incurred during the chase. The cost for the cheetah is that its paws are not particularly good at anything other than running; unlike most other cat species, cheetahs rarely use their paws for subduing prey beyond tripping it (see Chapter 5, page 104) and they also make poor climbers. Cheetahs do not ‘handle’ carcasses like other cats, and when eating they usually lie down with their legs tucked underneath them.

For all its limitations, the cheetah’s unique paw is a key element in the design for speed. Contrary to popular belief, cheetahs retain the physical apparatus to retract their claws. They have precisely the same elegant arrangement of muscles and ligaments in each toe that extends and withdraws the claws in all cat species. However, the changes in the cheetah’s lower limbs to ensure high speed result in a somewhat diminished action so retraction is only partial. Cheetahs also lack the protective sheath of skin that houses the claws of other cat species and hides them from sight. It means that the cheetah’s long, straight claws protrude even when retracted, acting like sprinter’s spikes to enhance grip; at high speeds, the claws are fully extended to maximise purchase.

The exception to the pattern is the cheetah’s dewclaw. Like all felids (it is easily seen in domestic cats), the dewclaw sits high on the cheetah’s forepaw, resting well above the ground. Sharply curved, sheathed and well served by muscular action, the dewclaw is crucial for hooking prey in the final moments of the chase. In fact, the cheetah’s dewclaw is, relative to its size, almost a third larger than a lion’s. With the modifications for speed in the cheetah’s forepaw, the dewclaw has assumed the predatory role served by all five front claws in other cats. Intriguingly, after the cheetah, the species with proportionally the next largest dewclaw among large cats is the puma.

In addition to the refinements of the claws, the pads of the feet are very hard, with heavy longitudinal ridges to increase traction and blunt points at the front, perhaps to assist rapid breaking. Even the cheetah’s tail plays a role; long, tubular and muscular, it provides balance for rapid changes of direction during the chase.

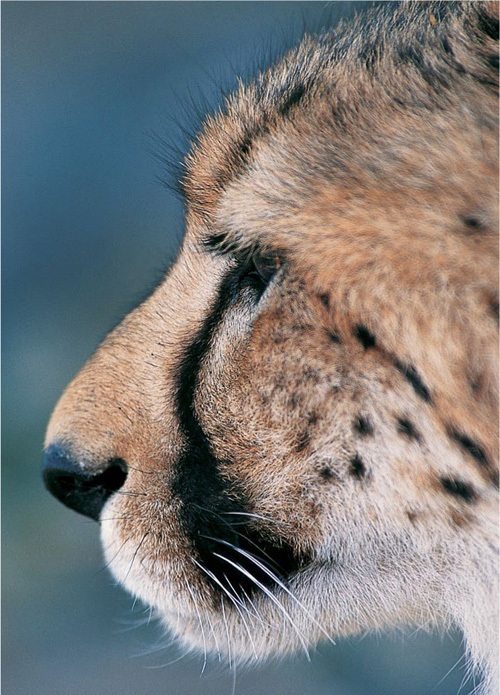

Cheetahs approach their physiological threshold during the chase. The body temperature soars to 40.5°C and the respiratory rate exceeds 150 breaths per minute, close to 10 times the rate at which a resting cheetah breathes. To cope with such extremes, the cheetah has yet more adaptations. Its skull is small and has shortened jaws to reduce weight. Additionally, it is equipped with proportionally smaller canines than other cats. Small canines have small roots, which creates space for enlarged nasal passages; this assists air intake and allows the cheetah to gulp air through the nose while maintaining a suffocating throat-hold on its prey. Cheetahs also have enlarged lungs and bronchi (air passages) which, when combined with the action of the oversized heart and highly muscular arteries, ensure the maximum delivery of oxygen. Even so, cheetahs are exhausted after a long chase and may take up to half an hour to recover before they can begin to feed.

The cheetah is the last in a unique line of sprinting cats. The reasons for the extinction of its European and American counterparts are not well established. Certainly a significant factor must have been gradual climatic changes, which resulted in wholesale turnover in the mammalian fauna. However, why this would claim the larger cheetah species and not the smaller forms is unclear. Similarly, in the case of the smaller Miracinonyx species that survived up until 10 000 years ago, the impact of human hunters on its prey is implicated, but its decline seems to have been already underway by the time humans reached the Americas. None of the explanations is entirely satisfactory but, as highly specialised predators, perhaps all cheetahs are vulnerable to extinction events. Only time will tell whether the modern cheetah is also facing an evolutionary dead-end.

The cheetah may represent the most efficient biomechanical design for speed in a quadruped. If true, any evolutionary modifications would come at a cost, meaning that the cheetah’s top speed may be the upper speed limit for four-legged mammals.

VARIATIONS ON A THEME

With its beautifully mottled markings, the king cheetah seems a very different animal to the more common spotted form. Indeed, when it was first described in 1927 from an animal killed in southern Zimbabwe, it was thought to be an entirely new species, Acinonyx rex. It turns out, however, that the difference is only skin-deep. The king pattern arises from a recessive mutation to a single gene controlling spot formation, making the king the cheetah version of a tabby. Kings and normally spotted cheetahs can be born in the same litter, although a king pair can only have king cubs. Historically, this striking variant was known only from a small region around north-eastern South Africa (including the Kruger National Park), Zimbabwe and eastern Botswana, but a king cheetah skin recovered from a poacher in Burkina Faso, West Africa, suggests the mutation occurs more widely. King cheetahs are rare but comparatively common compared to other coat colour variations. There are two known records of melanistic cheetahs, from Zambia and Zimbabwe, and a unique cheetah presented to the Mughal emperor Jahangir in 1608 was white with bluish spots. Two partially albino cheetahs have been recorded from South Africa while cheetahs in the Sahara Desert tend towards extreme paleness; some are described as almost white with very pale cinnamon spots. As science has never studied them, the extent of the variation is unknown.