The cheetah is a grassland specialist and hunts gazelles; at least, that is the popular notion. It is true that cheetahs are easily observed hunting in open habitat where they often kill gazelles or similar-sized prey, but cheetahs are considerably more flexible hunters than often portrayed. Cheetahs take sub-adult zebras, adult wildebeest and even young giraffes. They hunt on the serrated slopes of Central Iran, inside the thick bush of northern Kenya and in the depths of the deserts spanning north Africa. And although the high speed chase is typical of cheetahs wherever they occur, cheetahs in different habitats have a surprising range of hunting tactics in their repertoire.

There are few sights in nature as exhilarating as a cheetah on the hunt. Just when it appears that she is moving as fast as evolutionary law will permit, she accelerates further, a palpable shift in gears that takes a moment to grasp. And when your eyes tell you that now she is at her physiological threshold, she will speed up again – and again – as she closes the gap to her prey and brings the hunt to its culmination. At the highest point of the chase, she is reaching speeds at least as fast as the limits imposed by motorists on most highways around the world.

It is a thrilling display though, of course, for the cheetah it is purely about eating. Like all cats, cheetahs are obligate carnivores – they eat meat exclusively or require a diet overwhelmingly dominated by it – and in the case of the cheetah, it has to be freshly caught. Cheetahs very rarely scavenge (for reasons explained later in this chapter, see page 109) so every meal is the end product of a successful hunt. For that, the cheetah unites elements of the feline stalk-and-ambush strategy with a high-speed pursuit more characteristic of dogs. It is a method of hunting that the machinery of evolution has engineered dozens of times in the past, but today it is unique to the cheetah.

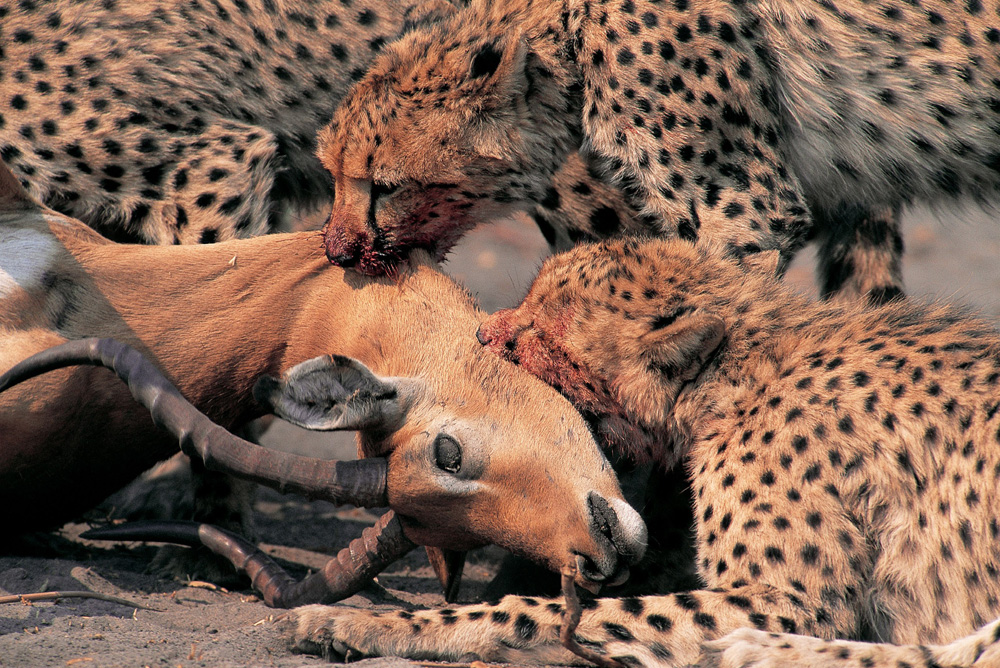

A large family such as this will finish off this impala in a few hours. Competition between cheetahs on a kill is manifested mainly in non-aggressive behaviour, primarily by accelerating the rate of eating.

CALCULATING PREY PREFERENCES

When zoologists use the term ‘preferred’ prey, they usually mean the species or type of prey that cheetahs kill most often. Serengeti cheetahs prefer Thomson’s gazelles, Etosha cheetahs prefer springboks and Zululand cheetahs prefer nyalas. But preference does not imply the cheetah is actually making a conscious choice between prey options; it might arise simply due to abundance. Nyalas are the most common medium-sized antelope in Zululand and cheetahs kill them essentially at random. In other words, the proportion of nyalas in cheetah diet reflects their numbers in the wild.

However, cheetahs often do exert a dietary choice. In Zululand, reedbucks are less common than nyalas, but cheetahs kill them at almost eight times their relative availability. This suggests that if given a choice, cheetahs are eight times more likely to take a reedbuck over a nyala, but even with such compelling statistics, we need to be careful. Whereas nyalas generally occupy dense woodland, reedbucks inhabit open grasslands and floodplains – perfect for cheetahs. The reedbuck’s unfortunate prominence in the cheetah diet might simply reflect the cheetah’s preference for open habitats rather than dense ones. To establish whether a true preference exists, we need to know the relative time cheetahs spend in different habitats, what they kill in each habitat, and what was available to kill in each habitat. It sounds straightforward, but it requires thousands of hours of observation to get it right.

THE GAZELLE CONNECTION

Compared to most species of large cats, the cheetah is locked into a strikingly particular diet. With the physical specialisations for speed comes a loss of predatory versatility so that, relative to the similarly sized leopard, which eats everything from dung beetles to baby elephants, the cheetah is principally an antelope specialist. Indeed, an inventory of prey species comparing the two cats reveals a predatory niche over twice as narrow for cheetahs; in Sub-Saharan Africa, cheetahs take around 50 different prey species compared to well over 100 for leopards. While these tallies are by no means exhaustive – they are derived from intensive studies only and do not include chance observations from elsewhere in Africa which would boost both totals – the contrast is clear.

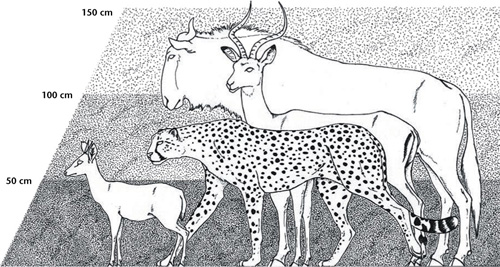

A representative range of prey sizes normally taken by cheetahs. The impala represents the preferred prey size, while the grey duiker (left) and adult female wildebeest represent typical (but not absolute) extremes.

(© Luke Hunter)

Certainly, where cheetahs are most easily observed, their specialisation on medium-sized antelopes is manifest. On the open grasslands of East Africa, two-thirds of all cheetah kills are the 25-kilogram Thomson’s gazelle. In southern Africa’s arid areas, the preferred quarry is the region’s only gazelle species, the slightly larger springbok, which makes up almost nine out of 10 cheetah kills in the Kalahari Desert. Similarly, although scientific scrutiny is yet to reveal precise figures for cheetahs hunting in the deserts of Mali, Niger and Chad, we know that mainly dorcas and dama gazelles are killed there.

Cheetahs are exposed to attack from other predators while feeding and constantly look around when on a kill. Their vulnerability makes them inclined to abandon kills if disturbed, behaviour that has given rise to the myth that they are wasteful killers and hunt for pleasure. If left alone, cheetahs remain on a kill until it is finished.

Gazelles arose in Africa and theirs is one of the few antelope groups to have been successful in colonising other continents. As open-country specialists, they proliferated in the steppes and dry grasslands of the Middle East and Eurasia, where they almost certainly featured high on the menu for Asiatic cheetahs. Sadly, we have few accurate observations of the cheetah’s eating habits outside Africa, but they were celebrated in India for targeting Asian repre-sentatives of the gazelle tribe, such as blackbucks and chinkaras (an Asian subspecies of the African dorcas gazelle). In the former Soviet Union, cheetahs were almost entirely dependent on the now-endangered goitered gazelle, whose intense persecution during the 1930s was one of the factors that drove the cheetahs there to extinction. The last of the Asiatic cheetahs clinging to survival in Iran still hunt goitered gazelles and chinkaras today.

Cheetahs often search carefully in long grass, looking for young antelopes left in hiding by their mothers. The best tactic for the calf or lamb is to lie immobile; cheetah colour vision is poor and they rely largely on movement or recognisable shapes to detect prey. Even so, it can be a productive hunting method for cheetahs.

At around 20 to 60 kilograms, gazelles are ideal prey for the cheetah, and virtually everywhere there are gazelles, there are (or were) cheetahs. However, cheetahs live in many areas where gazelles do not and it would be a mistake to view the cheetah as an inflexible gazelle specialist. From an evolutionary point of view, at least some dietary plasticity makes sense, even if it pales in comparison to the leopard’s. Few predators are wholly reliant on one type of quarry because the demise of the prey species would spell certain extinction; witness the end of the Russian cheetahs. Importantly in this case, though, the problem arose not because they were averse to prey other than the goitered gazelle, but because there was simply no other suitably abundant option. Had alternate prey species been available, the cheetah may have survived.

Two males in the final stages of the chase, on this occasion of a blesbok calf. Male coalitions occasionally release their prey and ‘play’ with it (as here) but it does not appear to happen often, probably because such behaviour might increase the chance of attracting competitors such as spotted hyaenas.

DO HUNTING CHEETAHS CO-OPERATE?

Although males in a coalition always hunt together, actual co-operation is mostly limited to ‘running interference’– distracting any adults that attempt to defend their youngsters. Male cheetahs only occasionally assist one another in pulling down large catches, and more often than not a single male succeeds in killing the prey without any help from a coalition partner. Furthermore, hunting cheetahs never drive prey towards a companion waiting in ambush. Cheetahs are essentially solitary hunters that have to take larger prey when they team up for the benefits of territorial defence (as discussed in Chapter 3, see pages 49–57). So, while single males are quite capable of killing animals considerably larger than themselves, they generally do not, unless the collective demands of a coalition require it. The risks of tackling large prey are simply not worth incurring when energetic needs can be satisfied more safely.

Where there are alternatives – any mid-sized antelopes – cheetahs prosper. In woodland savannah habitat from South Africa’s Kruger National Park to southern Kenya, cheetahs focus on impalas. With the males weighing up to 75 kilograms, impalas are larger than most gazelles but they nevertheless sit comfortably within the conventional idea of the cheetah’s preferred range of prey. Similarly, cheetahs in Zambia’s Kafue National Park take mainly the impala-sized puku, and when cheetahs were reintroduced into the Suikerbosrand Nature Reserve near Johannesburg, they targeted the comparable blesbok.

More surprisingly, cheetahs specialise in hunting nyalas in South Africa’s densely vegetated Zululand region of KwaZulu-Natal province. Reaching 130 kilograms in the male, this woodland antelope is far heavier than any gazelle species and, indeed, about twice as heavy as the largest cheetahs. The Zululand cheetahs are the only population studied to date whose preferred prey is so spectacularly outside the 20 to 75 kilogram range. But here, a side-note on preference is important to bear in mind: preferred refers to prey that cheetahs most often kill. At almost 50 per cent of their diet, nyalas are an unusually large preferred-prey item, but cheetahs anywhere are quite capable of killing such sizeable animals – and do so from time to time.

Cheetahs invariably move their prey (once dead) to cover, a strategy to avoid being spotted by vultures and other scavengers. Even so, they are not well equipped to drag prey, and unlike the drags of leopards, which may cover hundreds of metres, cheetahs typically opt for the nearest bush or tree.

The cheetah’s small canine teeth are well suited to applying an asphyxiating throat-hold to the narrow neck of antelopes, a further reason why species with wide necks are off-limits as prey. Although ‘neat,’ suffocation is actually a fairly prolonged process that can take up to 10 minutes.

Interestingly, coalitions of cheetah males routinely take adult male nyalas, but they constitute an extremely rare kill for female cheetahs; presumably, nyala bulls are too large or too dangerous for female cheetahs to hunt; they mostly kill the much smaller ewes. It is a pattern repeated throughout Africa, where male coalitions tackle larger prey to satisfy their combined daily needs. In the Serengeti grasslands, single males can sustain themselves by hunting Thomson’s gazelles, pairs may switch to the larger Grant’s gazelles and young wildebeest, while trios have to kill nothing smaller than yearling wildebeest or be forced to hunt again.

FIELD NOTES: AUGUST 17

06:05: Two male cheetahs are stalking a giraffe herd of about 10 adults and two calves. The cheetahs are moving from open clearings into acacia woodland where the giraffes are feeding. Suddenly, the cheetahs take off. The giraffes are caught unawares and panic as the cheetahs burst into their midst; they scatter, trying to make it to the grasslands where the adults will be able to cluster around the youngsters. It is difficult to follow the action, but I catch a glimpse of the two cheetahs harassing a female with one of the calves. Panicked, the calf runs ahead, deeper into the woodlands and away from the protection of its mother. One of the cheetahs takes off in pursuit. The mother giraffe seems to be looking for her calf, but one of the cheetahs is distracting her with lightning dashes at her ankles. She kicks repeatedly at him but he avoids her, using the cover of the trees. I catch up with the other cheetah just as he pulls down the calf. He trips it by hooking the ankle with his dewclaw and is instantly at its throat, applying the suffocating throat hold. I see the mother giraffe in the distance, her head appearing above the trees. She is moving away, with clearly no idea where her calf is. By the time the first male reappears to join his companion, the calf is dead.

A male cheetah on his juvenile giraffe kill, Phinda Game Reserve, South Africa. Adult cheetahs require about 4-5 kilograms of meat per day but, like all cats, they gorge when the chance arises. Able to eat 16.5 kilograms at a sitting, this male will feed from the kill for as long as he remains free of harassment from other carnivores.

Young giraffes count among the largest prey taken by cheetahs, but such substantial kills are uncommon and far smaller prey is the norm. In fact, when faced with a choice between adult antelopes and their young, cheetahs typically ignore the adults entirely. Newborn gazelles and impalas are swift but they are no match for cheetahs and a kill is virtually assured – East African cheetahs boast a success rate on newborn gazelles that approaches 100 per cent. Despite the greater pay-off of taking down an adult, hunting small prey carries essentially no risk of injury and requires little finesse; cheetahs make no effort to conceal their approach when targeting youngsters and trot openly at the herd from as far off as 600 metres.

Whether young or old, ungulates never comprise less than 80 per cent of cheetah kills, and in some areas the proportion reaches 99 per cent. After ungulates, hares are the next most-important ingredient of cheetah diet. They represent close to a fifth of kills on the Serengeti short-grass plains and in more marginal habitats, hares may be vital for the cheetah’s survival. Outside protected areas in Iran and Egypt, antelopes are now extremely rare and the hare is assumed to be the cheetah’s preferred prey. As both cheetah populations are now critically endangered (the cheetah may already be extinct in Egypt), the prospect for confirming this unique possibility is almost lost.

The balance of the cheetah’s menu is made up of a mixed bag of unusual species that, collectively, never comprise more than five per cent of kills. Cheetahs mostly ignore birds, but sometimes eat large species like ostriches, bustards and guinea fowl. They may take rodents, such as mole rats and cane rats, and while cheetahs rarely eat other carnivores, scattered records exist of jackals, bat-eared foxes, Cape foxes, caracals and banded mongooses as cheetah prey. In a unique observation from South Africa, rangers in Pilanesberg National Park witnessed cheetahs killing a young baboon that had become separated from its troop – the only reliable record of wild cheetahs preying on a primate.

Like all cats and contrary to popular portrayal, cheetahs often employ any available cover in their environment to stalk closer to prey.

STRATEGIES

The cheetah’s speed endows it with a winning edge over all other terrestrial mammals, but a successful hunt requires a great deal more than merely being fast. The evolutionary arms race has equipped its favourite prey with almost comparable pace, so that some gazelle species can clock speeds of around 90 kilometres per hour. And, critically for the cheetah, they are able to sustain it for much longer. The cheetah’s speed advantage has arisen by forfeiting stamina, forcing it to abandon the pursuit after no more than 500 metres, whereas gazelles can keep running for kilometres. It means that cheetahs cannot simply launch a chase from hundreds of metres away and, like all cats, they begin the hunt with a careful stalk.

Using the cover of bushes, termite mounds and occasionally even tourist vehicles, cheetahs endeavour to move to within 60 to 70 metres of the quarry without being spotted. If cover is sparse, they drop to the ground or remain motionless whenever the prey looks up. While typically feline, the process is usually far less protracted than the classic ambush hunter’s stalk; the belly-crawls and hour-long freezes favoured by leopards are rarely seen in cheetahs, and most stalks last less than five minutes. Even so, when faced with extreme conditions, the cheetah adopts an approach that has all the hallmarks of a leopard stalk. In the Sahara desert, where the absolute lack of cover often requires a painstakingly slow advance, cheetahs flatten themselves on the sand and remain motionless for long periods. Creeping forwards only when the quarry is grazing is a strategy that can bring the cat to within 30 metres of its target in daylight without being spotted. Recognising that the stalk is at least as important to the cheetah as its speed, the local Touareg nomads call the cheetah Adèle amayas – ‘the one who advances slowly’.

Cheetahs blend beautifully with the long, dry grass typical of the African dry season. It is difficult to establish how camouflage affects hunting success in cheetahs. Given that the stalking phase of their hunting method is usually fairly brief, camouflage is probably less important to them than it is to strict ambush hunters such as leopards.

If the stalk goes unnoticed, the cheetah unleashes its aston-ishing acceleration. Ironically, once the hunt is set in motion, it depends on its prey taking flight to make the catch. The cheetah’s technique relies on tripping its prey at high speeds, a strategy that does not require the physical strength used by lions and leopards to wrestle large prey to the ground. For the lightly built cheetah, such a close-quarter contest could be dangerous, and prey that stands its ground may diffuse the cheetah’s advantage.

FIELD NOTES: DECEMBER 12

18:45: I find three sub-adult cheetahs, two males and a female, just as they have cornered a male nyala. As I arrive, the nyala plunges into an ilala palm thicket and immediately turns to face its pursuers. It backs into the thicket and lowers its horns at the cheetahs. I am amazed to see that it is completely blind and is flailing its horns around aimlessly, presumably hoping to thwart any attack from the cats. The three cheetahs appear confused and hesitant. From time to time, they creep forwards as though to launch an attack, but whenever the bull hears movement, it slashes out viciously. It never comes close to injuring the cheetahs but it certainly keeps them at bay. After 25 minutes of this, the cheetahs move off, leaving the nyala unharmed. The departing cheetahs repeatedly glance back at the bull with somewhat bewildered expressions.

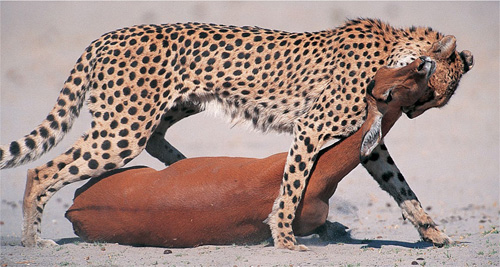

Of course, in the great majority of cases, the prey does run and in doing so, unwittingly provides the cheetah with the momentum that does most of the work. At high speeds, the cheetah needs only to land a raking blow with its dewclaw and the target stumbles. The effect may simply be one of tripping, particularly when the cheetah strikes the lower legs, but more often the action actually pulls the prey off balance. The cheetah hooks the prey with the dewclaw and then, braking abruptly, uses its weight to wrench the fleeing quarry to one side. Almost invariably, the technique leaves a distinctive tear wound in the prey’s rump or shoulder – the characteristic trademark of a cheetah kill.

A single cheetah tackles an adult red lechwe, Botswana. Hunts such as this – where a clean takedown does not immediately result – present a very real danger for cheetahs. It would be even greater if antelopes defended themselves more aggressively. Surprisingly, a number of prey species are slow to employ their weaponry when attacked, perhaps the only reason this cheetah escaped from this encounter unharmed.

Open plains and sandy deserts are ideal terrain for the high-speed chase but cheetahs exist in many different habitats and are able to modify their hunting methods accordingly. As displayed by the giraffe-hunters of Zululand, in areas where thick vegetation impedes their chances of ever reaching top speed, cheetahs use a harrying technique based on confusion and cover rather than sheer pace. Cheetahs employ a further tactic in habitats with a mosaic of open areas and scattered thickets of dense vegetation. Moving from one thicket to another, they search for hares and small antelopes like duikers and steenbok, which are flushed into the open and easily run down. Stands of long grass or low scrub are similarly quartered for small game, and here cheetahs may even use a succession of bounding leaps to lift them above the vegetation as they try to pin down the location of fleeing prey.

THE RISKS AND REWARDS OF HUNTING

Clearly, then, the cheetah is a considerably more versatile hunter than the classic television documentary portrayal, and enjoys a high success rate relative to other carnivores. Compared with an average of 25 to 30 per cent for lions, about 50 per cent of cheetah chases end in a kill. For certain prey, the figure climbs higher: nine out of ten hunts on hares in the Serengeti yield a kill, a statistic that outshines the success rate of even Africa’s most efficient large predator, the African wild dog.

Occasionally, cheetahs may make little effort at concealment when approaching prey and walk directly at the quarry in full view. It may be a strategy by which cheetahs ‘test’ prey, determining if any individuals in the herd are injured or vulnerable by alarming them into action. Even so, most kills made by cheetahs appear to be of healthy animals and more research is needed to clarify this question.

The young of large prey species such as this zebra foal are vulnerable to male coalitions but not to single cheetahs; large ungulates can defend their young from attacks by loners which is why zebras rarely feature in the diets of single males and females.

Like wild dogs, though, cheetahs often lose their kills to competitors. With their slight build, shortened jaws and dog-like claws, cheetahs are no match for other large carnivores and will relinquish a kill rather than risk injury by defending it. In woodlands, where cheetahs are less conspicuous, they rarely lose more than five per cent of kills but the deficit can exceed 15 per cent in more open habitats. Lions and spotted hyaenas are the main kleptoparasites (or ‘food thieves’) but leopards, wild dogs, brown hyaenas, and occasionally striped hyaenas and baboons, are able to drive cheetahs from their kills. Spotted hyaenas sometimes even follow cheetahs on the hunt, hoping to claim an easy meal if the cheetah succeeds. If pressed, a cheetah will abandon its efforts until the hyaena loses interest. Combined with their losses to other predators, such harassment forces them to hunt an average of 10 per cent more often than when left alone.

In the partially flooded grasslands of Botswana’s Okavango Delta, male coalitions are known for targeting male red lechwe, which range further than females from the protection of deeper water. Reportedly, the cheetahs here have perfected a technique of handling the large, unwieldy males by drowning them, but more observations are required before this can be confirmed.

Surprisingly, cheetahs almost never offset the costs of kleptoparasitism by scavenging themselves. Male cheetahs occasionally appropriate carcasses from females, but normally they go out of their way to avoid carcasses not their own. Presumably, it is not worth running the risk that the owner will return. Instead, cheetahs reduce their losses by hunting during the day when their competitors are less active. Diurnal hunting also makes sense because cheetahs need to be absolutely certain of their footing. At 100 kilometres per hour, an unnoticed snag or misplaced stride on uneven ground can be disastrous, even when conditions are perfect. Recently, a female cheetah hunting in broad daylight in South Africa’s Londolozi Game Reserve was disembowelled while clearing a tree stump at high speed. She died within minutes. Despite the risks, cheetahs do occasionally hunt at night, provided the habitat is very open and visibility is excellent. The cheetah’s night vision is quite good, and bright moonlit nights in the arid wilderness of Niger or northern Namibia every so often produce the rare spectacle of nocturnal cheetahs on the chase.

A young cheetah practises its suffocating bite on an already dead common reedbuck; the mother cheetah behind made the kill and is recovering as her cubs play with the carcass. Note the wound on the reedbuck’s front leg, inflicted by the female’s dewclaw when she took it down.

Cheetahs may also incur injuries from their prey, particularly when bringing down large animals. The cheetah’s lunging grab with the dewclaw is a technique requiring precision timing, particularly when the quarry is larger and travelling at top speed. Sometimes, a cheetah becomes tangled in the fall and tumbles violently with the prey. Surprisingly, although such mishaps may be quite common, serious injuries are not. Cheetahs often limp for a few days after a particularly strenuous hunt but presumably the damage is no worse than a slight muscle tear or strain because they nearly always recover.

Similarly, severe wounds inflicted by prey defending itself are fairly unusual. This is unexpected, given the extremely perilous situations in which hunting cheetahs sometimes find themselves. Serengeti researcher Tim Caro once saw a wildebeest kick a cheetah 1.5 metres into the air, sending the cat sailing through a backwards somersault. Amazingly, it landed on its feet, apparently unhurt. Very occasionally, the outcome is far worse. Wildebeest, gemsbok (oryx), warthogs and even large breeds of cattle have been recorded killing cheetahs, but the victims are usually inexperienced youngsters who fail to trip the prey cleanly and become caught in a frantic struggle. Catastrophic miscalculations like this are exceptional, though, and most cheetahs will survive such encounters with nothing more than a few bruises and a valuable lesson.

Three male cheetahs work at the last meat on a kill. Kills made by cheetahs are easily identified because, as in this picture, most of the large bones and spinal column are untouched leaving a distinctive, largely intact skeleton stripped of flesh.

When subduing prey, experienced cheetahs orient themselves away from the horns and hooves of struggling animals to avoid injury. Exposure to such subtleties might be acquired during the training process when mothers release live prey for their cubs. It means that, by the time young adult cheetahs are hunting alone, as are these recently independent males, they are competent enough to deal with well-armed prey like male impalas.