The social and ranging behaviour of the cheetah is unique among cats. Most cat species are both solitary and territorial - adults defend an area from rivals and rarely meet up with other individuals except for transient liaisons among mating pairs. Cheetahs, however, bend the feline rule, and do so according to sex. Like other cats, male cheetahs are usually territorial but, instead of defending a patch on their own, they form intimate, lifelong associations with other males. Females, on the other hand, follow the feline pattern of being solitary - but unlike other cats, they never establish a territory.

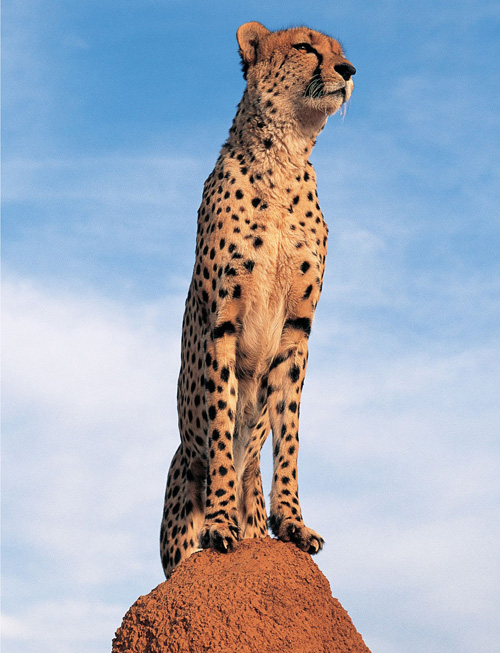

Cheetahs are very visual animals and constantly seek out high points like termite mounds to scrutinize their environment. Their long distance vision has never been accurately assessed but they easily discern gazelles at distances of more than two kilometres.

When it comes to social behaviour in cats, the model is to go it alone. Most of the 36 species of wild felids are solitary as adults; both males and females establish their own exclusive territory and go to considerable lengths to defend it against intruders of the same sex. They proclaim their occupancy of an area with scent-marks and long-distance vocalisations, which are occasionally backed up with lethal force.

The obvious exception to the rule is the lion. The lion is the only felid in which both sexes form associations that last for life. Male lions group together in enduring brotherhoods called coalitions, usually made up of same-aged male relatives – the brothers and cousins born into a pride, who are evicted collectively as young adults – but some contain unrelated males. In the case of lionesses, their bonds are always formed between female relatives, the great resilience of which creates the core of the pride. As in solitary cats, both sexes establish territories. Lionesses defend their territories from other prides, and male coalitions exclude other males from theirs.

In cheetahs, social and ranging behaviour falls somewhere in between the highly social lion and the solitary lifestyle of all other cats. It is a fascinating, flexible arrangement that is not found in any other wild felid and, in fact, is yet to be demonstrated in any other carnivore.

THE FEMALES: SOLITARY AND NOMADIC

Female cheetahs basically follow the feline model, at least with respect to sociality. They do not form social groups with other adults and they associate with other cheetahs only during the brief period during which they are receptive to males for mating. But, unlike other female cats, they do not establish a territory. Female cheetahs never actively exclude other cheetahs from their space and therefore cannot be regarded as territorial. Instead, the undefended area they occupy is termed a home range, and each female’s range overlaps extensively with those of other females. In East Africa, up to 20 females have been counted using the same area but, unlike territorial cats, clashes between them are nonexistent. Female cheetahs usually move away from other females they see in the distance, or merely ignore them.

Although females rarely associate with other adults, they actually spend the majority of their adult lives accompanied by other cheetahs - their cubs.

The home range of a female may be vast. On the Serengeti short-grass plains, ranges are rarely less than 395 square kilometres and may exceed 1 200 square kilometres. In Namibia, female home ranges are even larger, reaching 1 500 square kilometres. In both populations, the same factor drives the pattern: availability of prey. Serengeti females enjoy high densities of their primary prey, Thomson’s gazelles, but they are migratory (see Chapter 5, pages 90–100, for details about diet). The gazelles track the transient flushes of new grass that ebb and flow across the plains according to seasonal rainfall, a process that creates localised and highly mobile concentrations of antelopes. In ecological terminology, this leads to a distribution of prey known as ‘patchiness’. Female cheetahs can subsist on any one ‘patch’ of gazelles for as long as it endures; indeed, they use areas as small as 30 square kilometres for some weeks while the herds remain. Inevitably, though, the gazelles’ own resource requirements drive them to seek out new grazing, and the cheetahs are impelled to follow.

Namibian females also have to deal with a similar patchy spread of herds, but are faced with the additional challenge of lower initial prey densities. Namibia’s semi-arid bushveld does not support the Serengeti’s high concentration of prey, so the ranges of Namibian cheetahs have to be even larger. Similarly, although science does not yet have the figures, we can reliably predict that females in the extreme habitat of the Sahara probably have the largest home ranges of all.

The smallest ranges belong to females that can rely on their prey staying put. In southern African woodlands where cheetahs hunt mainly non-migratory antelopes such as impalas and nyalas, females occupy ranges as small as 34 square kilometres. Provided that sedentary prey is uniformly distributed at fairly high densities – in other words, is not patchy – cheetahs are freed of the obligation to cover huge distances as those in the Serengeti must. Intriguingly, although such a small home range would be easily defended, South African females are just as non-territorial as their East African counterparts. Like female cheetahs everywhere, the occasional meetings between them are essentially amicable.

FIELD NOTES: JULY 12

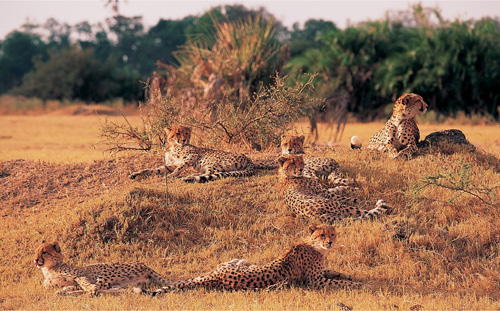

07:45: The female Mahamba is resting with her three cubs when a second female cheetah – with five large cubs – appears in the distance. The new cubs are racing ahead of the mother, play-chasing each other, when one of them bumps into Mahamba and family. All the cheetahs are startled and scatter, then Mahamba stops and calls her cubs to her. The other female’s cubs race over, perhaps thinking they are being called. For about 15 minutes, there is a chorus of chirping, growling and hissing as the cubs work out who is who. Mahamba is mildly upset and twice spits explosively at the new cubs, but she soon relaxes. The new female seems completely unperturbed by the interaction and flops to the ground in the middle of the cubs, ignoring all of them. The 10 cheetahs gradually settle down to rest, all within touching distance of each other. From time to time, the cubs from the different families seem eager to interact with one another but any tentative playful gestures trigger another outburst of uncertain spits and hisses from all the cubs. They stay together for two hours, resting peacefully for most of the time, and looking like a single large family. At 09:45, the second female gets up abruptly, stretches and walks away, heading south. Her cubs follow. Mahamba and her three cubs watch them depart, then move off in the opposite direction.

Curiously, some South African females wander over much larger ranges, even when the availability of prey would seem to predict otherwise. A female and her cubs monitored for 12 months in South Africa’s Kruger National Park had a record range of 1 848 square kilometres. Presumably, factors other than the distribution of prey were shaping her movements. Perhaps the extremely high density of cub predators such as lions and spotted hyaenas in some areas of Kruger pushes females to keep moving, though cheetahs there are still too poorly studied for there to be any certainty.

Whatever the size of their range, females follow a characteristic pattern of traversing it. They typically spend a few days to a few weeks hunting locally in one slice of their range before travelling to another area and doing the same. In Serengeti females, these treks regularly cover up to 10 kilometres in a day, and females may continue walking for some time. Researcher Karen Laurenson followed a female over the course of five days in which the animal moved 33 kilometres, walking steadily in the same direction. For females that can rely on resident populations of prey, the need to commute is alleviated and the pattern of movement is less distinctive. Treks between hunting sites are smaller, often only a kilometre or two, and they are more frequent, resulting in a pattern that sees the home range covered more systematically.

WHY DO FEMALE CHEETAHS NOT FORM COALITIONS?

Excluding feral domestic cats in which enduring alliances sometimes develop between related females, lions are the only felid species in which the females form groups. Given the advantages of coalitions to male cheetahs and to lionesses, it begs the question: why are female cheetahs always solitary?

In lionesses, communal defence of their cubs against infanticidal males is thought to be one of the evolutionary forces promoting sociality. Given that infanticide is very rare or perhaps never occurs in cheetahs (see Chapter 4, page 72), females have little to gain from teaming up if that is their only concern. Another theory suggests that the visibility of open plains compels lionesses to remain together because they are so conspicuous on large kills: better to share kills with relatives than surrender them to unrelated individuals spotting a free meal from afar. Again, cheetah females have little to gain here because they rarely make large kills that they cannot finish in a day, and they naturally live at low densities, so losing a meal to other cheetahs is unlikely. Equally, defending a kill against other predators is an improbable gain because even a group of cheetahs could not repel lions, leopards or hyaenas.

Finally, females could conceivably enjoy foraging benefits if coalitions were more successful at making larger kills (as they are in male cheetahs), but the advantages probably do not outweigh the combined costs of feeding extra mouths and tackling large prey. Although their relative importance is vague, the combined effect of these factors means that sociality in female cheetahs simply does not make sense.

The great mobility of females means that they often cross paths with other cheetahs. It sets the scene for a remarkable feature of their society – adoption. From time to time, encounters between females result in the cubs from different families getting mixed up. In most cases, an unrelated cub is tolerated, although the adoptive mother clearly distinguishes it from her own youngsters: females repel foreign cubs from close contact, occasionally slapping them and never allowing them to suckle (at least, in all observed encounters). Even so, mothers make no serious effort to drive away strange cubs, and they are usually accepted to be raised with the rest of the litter. For cubs that have been orphaned or have lost contact with their biological mothers, this is probably their only hope of survival. In fact, lost cubs may even attach themselves to adult males in their desperation to subsist, though these associations are very rare and seldom endure beyond a month.

Adoption is extremely uncommon in wild cats and the reasons it occurs comparatively often in cheetahs are still unclear. There are certainly no advantages to the mother; cubs, adopted or biological, do not contribute in hunts nor do they remain with the female to help raise subsequent litters, as happens in some other species that practise adoption. Similarly, kin selection – in which an individual gains reproductive benefits by helping a relative to reproduce – is unlikely to be operating because the chances of an adopted cub being related are very low. It is true that the home range of female cheetahs often overlaps with their mothers’, setting up the possibility that a lost cub belongs to a female relative. However, given the enormous distances covered by females and the number of different females that may share space, the likelihood that the cub belongs to an unrelated mother is far greater.

Presumably, then, the costs to the mother of feeding one extra mouth must be too trivial to warrant her expending the energy in driving off the adoptee or even killing it. By the same rationale, though, female cats of many species should become foster mothers more often, and they very rarely do. Perhaps the female cheetah’s non-territorial nature and concomitant docility towards other cheetahs predisposes her to being easily exploited by lost cubs. Compared to those felid species that routinely defend their territories against unrelated trespassers, the notion of attacking cubs – even strange ones – may be lacking from the evolutionary makeup of the female cheetah. Whatever the explanation, so long as the adopted cub is persistent in keeping up with its new family, it seems that the reluctant mother simply gets used to it.

Unless adoption is witnessed, it can be difficult to distinguish an unrelated cub from its adoptive siblings as they will end up interacting with a new cub as one of their own. An obvious size difference among the cubs is a sure sign, but more subtly, close contact like this is very rare between a female and an unrelated cub.

A female cheetah (back, right) with her five adolescent cubs, almost at the age they will become independent. The cubs will remain together as a sib-group for a few months after they leave their mother. Brief interactions between different sib-groups and females with adolescent litters explain occasional sightings of cheetah groups numbering up to 16.

THE MALES: SOCIABLE AND SEDENTARY

For female cheetahs, being solitary and nomadic is evidently the best tactic – or at least a sufficiently effective one – for meeting their needs and raising cubs. Males, however, have different requirements and pursue a very different social strategy in order to achieve them. In the same way that male lions form permanent coalitions, most male cheetahs remain in small groups for life. Numbering up to five, but most often just two or three, coalitions are generally made up of brothers born into the same litter. When young cheetahs gain independence from their mothers, the females ultimately pursue a solitary existence but the males stay together. Indeed, if a male cheetah has no biological brothers, he may attempt to link up with unrelated males and as many as 30 per cent of all coalitions contain at least one unrelated member. Most mixed coalitions are composed of two loners who have united, but single males sometimes join an established pair and rare cases exist of a singleton being accepted by a trio of brothers.

The compulsion to be part of a coalition is a powerful one for male cheetahs, suggesting that there must be significant advantages to having companions. Easily the most compelling benefit is in acquiring territory. In contrast to female cheetahs, but similar to the males of most felid species, male cheetahs are territorial. From about the age of four, male cheetahs attempt to occupy an exclusive area that they defend rigorously from other males. Not surprisingly, the numerical advantage of coalitions gives them a significant edge over single males and, in fact, coalitions are about six times more likely than a loner to acquire a territory. Oddly, however, there is little evidence to suggest that they are more successful at holding onto a territory once they have secured it. Although singletons rarely win turf, they tend to occupy it for just as long as coalitions if they do. Regardless of group size, the average tenure is about the same, four to four-and-a-half years. There is no obvious explanation for the inconsistency. The process has been well studied only on the Serengeti short-grass plains, and studies of different populations or, for that matter, longer-term monitoring of the Serengeti males may well reveal a different pattern.

Territory holders assiduously mark their turf with urine and faeces, depositing them most often at the boundaries, but any prominent points such as large trees and termite mounds throughout the territory are invariably marked. Scent-marks inform potential interlopers that the area is occupied and other males ignore the warning at their peril.

Marking behaviour in male cheetahs is very ritualised, with all members of the coalition contributing to the collective smell. Urinating on prominent points takes place at a prodigious rate but defecation typically occurs only two or three times a day at early morning or evening.

Fatal clashes over territory occur often enough to be a significant source of mortality to male cheetahs. After deaths by other large carnivores, they are the most likely reason a male cheetah will die in some populations. Additionally, they illustrate that the pay-offs for holding a territory must be great, certainly enough to outweigh the very substantial risks of fighting.

Not surprisingly, the chief reward for territorial males is females. Like all male cats, male cheetahs are willing to fight if it substantially increases their chance of reproductive success. For cats in which the females are also territorial, the general pattern is clear: males attempt to set up a territory that encompasses as many females’ territories as possible. In solitary species such as leopards, pumas and tigers, this translates to male territories of about three to four times the size of the average female territory. Coalitions of male lions follow essentially the same process – they attempt to overlap the territories of a number of female prides. For all these species, the upper limit of the territory is determined by the size of an area that a male can successfully defend from intruders. A huge territory might encompass many females but is too large to defend adequately, whereas a very small, easily defended territory might only secure access to a single female. Where possible, male cats attempt to strike a balance somewhere in between these extremes.

For male cheetahs, there is an obvious dilemma. The females of their species do not establish small, discrete territories, and their enormous home ranges are impossible to hold against other males. However, female ranges do overlap extensively. Exploiting the situation, male cheetahs adopt a unique variation on the feline territorial strategy. Rather than attempting to encompass entire ranges, they pinpoint the most productive areas within them. Males position their territories around female ‘hotspots’ – small, defendable areas rich in the resources that attract female cheetahs.

The males of this adolescent litter are virtually certain to remain together for life. Having many brothers surviving to independence age means that the males in this litter are likely to acquire a territory.

THE ADVANTAGES OF SOCIALITY

Reproductive rewards are probably the principal reason that males form coalitions (see pages 49–57) but sociality also brings better feeding. The members of Serengeti coalitions eat slightly more per day than lone males, achieved primarily by killing larger animals. Why then do scientists believe that reproduction and not foraging is the engine driving sociality in male cheetahs? The answer lies in how each is affected by living in groups. Lone male cheetahs are perfectly capable of meeting their energetic requirements, even if they have to hunt a little more than coalitions to do so, but their chances of securing females are extremely low. In other words, all cheetahs, whether alone or in groups, manage to forage efficiently enough, but males in groups are far more successful at siring cubs. (For more on hunting in coalitions, see Chapter 5, pages 95–96.)

On the plains of the Serengeti, the most important of these resources is cover. Surprisingly, perhaps, males do not situate their territories in the areas with the highest concentrations of Thomson’s gazelles, even though the females track their migrations. There are a couple of reasons for this. Female cheetahs actually avoid the largest herds of gazelles because these also attract other predators, such as lions and spotted hyaenas. Instead, they prefer intermediate concentrations of gazelles, which are less likely to draw dangerous competitors but nonetheless provide profitable returns for the effort of hunting. Additionally, hunting gazelles where there is no cover to conceal the approach is far less likely to produce a kill, while females also need cover as lairs for their cubs. So the best hotspots, and therefore the most sought-after territories, have numerous thickets, drainage lines or koppies, and also contain ample – but not very large – prey populations.

In Southern Africa’s acacia woodlands, cover is again the critical factor. However, it is its absence rather than presence that makes all the difference. There, cheetahs seek out small patches of open grassland and palm savannah within the dense bushland mosaic. Cheetahs hunt in all habitats (see Chapter 5, pages 101–104) but they make most of their kills around the edges of these open patches, so females are often found there. Importantly, the distribution of female hotspots in the woodlands may differ markedly from that on the plains, creating male territories with very different characteristics. In the Serengeti, the foci for territories are often bunched together, with large distances separating discrete clusters. The result is small territories averaging slightly more than 37 square kilometres (less than five per cent the size of the average female home range), which are widely separated by tracts of land devoid of resident males. In southern Africa, where grassy fragments are often distributed more uniformly, male territories border one another without vacant gaps and they are larger, between 60 and 160 square kilometres.

Combining the features of territoriality in woodland males with the smaller ranges of females there, the overall pattern begins to resemble that in felid species where both sexes establish territories. Although female cheetahs in the woodlands are non-territorial, their smaller ranges might enable a single coalition (or a single male) to establish a territory that entirely overlays the female’s range. In the manner that male leopards, tigers and lions attempt to monopolise females for the duration of their tenure, woodland cheetahs may be able to do the same. In contrast, plains males constantly compete with other males in that the pool of females available to them is endlessly circulating between many male territories. In the end, though, whether woodland males outpace plains males in the ceaseless competition to perpetuate their genes is entirely unknown.

CHEETAH VOCALISATIONS

Among mammals, sociality is broadly correlated with a more complex repertoire of vocalisations. Social species communicate more regularly than solitary ones and require a better vocabulary to do so with precision. Social behaviour in cheetahs is not sophisticated enough to demand an especially intricate ‘language’, but they do have some unique calls.

Perhaps the most distinctive of their calls is yipping, a high-pitched barking call that cheetahs use to locate one another. Mothers yip to find lost cubs and males or adolescent littermates yip when separated from one another. In cubs, yipping sounds much like a bird cheeping and is usually called chirping. Lost cubs chirp and also use this vocalisation in moments of social stress – for example, to appease unfamiliar male cheetahs. A shrill variation of yipping, the yelp is used by adults when fearful.

Cheetahs also churr (also known as stuttering or stutter-barking) during many social encounters. Friendly cheetahs churr as a social invitation, for example, when mothers gather their cubs to suckle, whereas unfamiliar cheetahs churr loudly to express interest, uncertainty or appeasement. Males churr excitedly almost continually during liaisons with females, while females in the same context churr to express anxiety.

Like all cats, cheetahs growl, hiss and spit, either when annoyed with one another, or at danger. They also yowl, a drawn-out moan uttered when a threat is escalated – for instance, mother cheetahs yowl stridently when they confront predators attacking their cubs.

Finally, while technically not a vocalisation, cheetahs purr in pleasant social exchanges, particularly when grooming one another. (See Chapter 2, page 31 for more on purring.)

THE FLOATERS: ON THE FRINGES OF CHEETAH SOCIETY?

For territorial males, the ultimate pay-off is access to females. Female cheetahs spend more time on male territories than outside them and the best territories can enjoy a succession of visits from different females as they pass through the area. So far, though, no one has carried out the genetic analyses that would establish whether territory holders actually sire the most cubs. Conceivably, the necessary comparison could be made against the success rate of a final cohort of cheetah society — the non-resident male, or floater.

Given the significant health costs for solitary floaters, they almost certainly do not live as long as territorial males. Accurate figures are difficult to compile because most cheetahs simply disappear, but data from the Serengeti suggests that, on average, floaters die about a year earlier than territory holders.

The members of male coalitions – whether territorial or floating – remain in close proximity almost constantly. When separated from each other such as sometimes occurs during the confusion of a hunt, they call repeatedly until reunited.

Floaters are males who do not occupy a territory. Instead, they wander over vast home ranges comparable in size to those of the female. Serengeti floaters have home ranges that average 777 square kilometres. All male cheetahs begin their adult lives as floaters. As adolescents recently separated from their mothers, they lack the physical size, and perhaps the experience, to challenge adult males for territory, and they live a roving existence in which they have to avoid territory holders. If caught on an occupied territory, there is a chance they will be killed. For most young floaters, their enforced wanderings will take them far from their natal range (the area they were born) where, as adults, they will attempt to secure their own patch of turf.

Some of them never succeed. If single males fail to team up with other males, chances are they will not be able to win a territory. Loners are sometimes fortunate enough to move into a vacant territory, but otherwise they live a furtive existence with very real costs. Floaters are more nervous than residents, spend more of their time vigilant, and try to avoid being seen. They move a great deal more than residents, usually after dark, and they avoid prominences such as koppies and termite mounds, where they might be spotted by resident males. Perhaps most compellingly of all, they are in poorer condition. Compared to residents, floaters weigh less, have lower muscle mass and have elevated levels of corticosteroids, hormones whose levels soar in response to stress. They also have higher white blood cell counts and raised levels of eosinophils, a specific type of white blood cell that fights infections. Both are indicative of various types of chronic infections and allergic diseases.

Compared to territorial males, floaters spend about twice as much of their day sitting upright rather than resting. They also spend a greater percentage of their day on the lookout, presumably keeping watch for territorial males.

Not all floaters are single males. Coalitions may also be non-residents and, in fact, the members of most resident coalitions will ultimately become floaters if they are not killed on their territories. Having started out leading a floating existence as adolescents, old males are eventually forced back into this pattern when evicted from their territory by younger adults in their prime. Coalitions of floaters mostly suffer the same syndrome of consequences as loners but, curiously, some floating coalitions are in excellent health. The explanation illustrates the enormous flexibility in cheetah society. Resident males in the Serengeti sometimes leave their territories voluntarily. When one considers the great mobility of the Thomson’s gazelles and the fact that female cheetahs follow them, the obvious question is, how can male cheetahs survive by remaining? To some extent, they are able to meet their needs by taking non-migratory prey species such as warthogs (which females mostly leave alone), but there are times when they abandon their turf. Such excursions average about 20 kilometres from the territorial boundary, but may be as long as 65 kilometres. Strictly speaking, these trips do not necessarily make floaters of territorial males, especially as most will return to their territories, but on occasion they will be wandering away from familiar ground for some weeks.

Indeed, some coalitions probably float for life. If gazelles are periodically scarce on territories, then so too must be the reason for owning a territory – that is, female cheetahs. Although females collect at certain times of the year in specific areas, their wide-ranging movements mean they can be encountered anywhere. In terms of the reproductive pay-offs, coalitions of floaters might be able to locate as many – or perhaps even more – females by roaming around looking for them, rather than defending a territory and waiting for females to move onto it. Floating coalitions may even venture into occupied territories in their search for females.

FIELD NOTES: JUNE 16

06:25: The territorial Northern Marsh pair is very agitated, sniffing repeatedly at a large termite mound and urinating and scraping constantly. About 60 metres away, I see the reason for their consternation: two new males. The new pair is lying down, watching the resident males closely but without any visible anxiety. They appear relaxed even though this location is deep inside the Marsh pair’s territory. The resident males are walking stiff-legged and slowly (demonstrating to the new males) between trees and termite mounds, all of which are extensively marked. They move in a wide circle around the new males but never approach them. At 07:40, the resident pair lies down and rests. During the day, the two reiterate their marking routine numerous times while the new males watch without responding. At 15:10, almost nine hours after I first sighted them, the new males rise and head west without so much as a backward glance. This is the first good look I have had of them. Both are large adult males and appear in excellent condition. The Northern Marsh pair spends 20 minutes sniffing and marking where the new males have been resting and then walk away in the opposite direction.

Young floaters and solitary males normally respect territorial boundaries fairly strictly, but for adult males in floating coalitions, entering territories clearly carries fewer risks. Territorial coalitions are reluctant to enter into a potentially fatal conflict unless they have the weight of numbers or age. So, floating coalitions of adult males not only have access to any females they locate outside territories, they probably also find some females on territories that the resident males have missed. It remains to be seen which strategy yields the greater pay-off in terms of the number of cubs sired. Perhaps it is a combination of the two, and some males may adopt both strategies during the course of their lives. In any event, it demonstrates that no rules in cheetah society are carved in stone. Doubtless, as zoologists extend their research to other populations in different habitats, we will discover increasingly more about the factors that mould their intriguingly variable society.

FIELD NOTES: MAY 27

07:05: The territorial pair, Carl and Linford, are hunting about 150 metres in the distance. A moment after I first sight them, they take off after something, but the grass is very long and I am too far away to see what they are chasing. I lose them and relocate them at 07:15. I am stunned to discover that they are in the process of killing another male cheetah. Carl is throttling the male in the manner of killing prey, only much more aggressively, and Linford is mauling the flank. They are both extremely agitated. The third cheetah is already close to death and beyond resisting, but there must have been a brief skirmish as both attacking cheetahs have deep bite wounds on their cheeks and ears. They maintain their holds for 15 minutes, by which time the third male is dead. Carl and Linford rest briefly then fall upon the dead cheetah again, attacking the carcass as though to make sure it is dead. Time after time, they continue to maul the dead cheetah, interspersed with brief rests until 08:00.

ANTISOCIAL BEHAVIOUR: CANNIBALISM IN CHEETAHS

Although it is rarely witnessed, territorial clashes between male cheetahs sometimes result in the victors cannibalising their killed rivals. Typically, only the large muscle groups of the hind legs are eaten, but cases exist in which virtually the entire carcass was consumed. Cannibalism is often characterised as ‘aberrant’, but it can also be viewed as a strategy by which the victors recoup some of the energetic costs of territorial defence. Fights between male cheetahs are extremely stressful and energetically expensive for the combatants, so if a coalition does kill an intruder, it might make sense to eat him after the event. Oddly, though, more records exist of killed males being abandoned than of them being eaten, so the motivation for cheetah cannibals is still open to investigation.