The History of the Book in Korea

BETH MCKILLOP

In Korea and throughout East Asia, engraved intaglio seals and texts cut on stone steles were precursors of printing as a widespread technology. In neighbouring China, the fixing of classic texts as engraved stone slabs in AD 175 is an important landmark. Early political groupings on the Korean peninsula also recorded texts on stone and later took black-and-white ink-squeeze rubbings on paper from such engraved slabs. Intensive contact with China had led to the spread of Chinese script and knowledge of the Chinese language in Korea by about the 1st century AD. Chinese characters, which have both a semantic and a phonetic element, were used to write Korean words by following their sounds. Educated Koreans also learned to read and write in Chinese. From about the 6th to the 15th centuries, this complex and confusing system of borrowing Chinese script was the only one used to record the Korean language.

The earliest surviving writings using the native transcription system are poems. Texts from the Three Kingdoms period that survive as physical objects include a massive memorial slab—more than seven metres high and engraved with 18,000 seal-script Chinese characters, praising King Kwanggaet’o (who ruled the northern Kingdom of Koguryŏ, AD 391–413)—and an engraved stele (AD 503) from Yŏngil, North Kyŏngsang Province. It is a slab of granite, polished for engraving on three sides; bearing 231 characters of various sizes, in an archaic style, it records the judgement of a dispute about land ownership. The preservation of written words for posterity has been an enduring preoccupation on the Korean peninsula.

Papermaking had probably reached Korea from China early in the Three Kingdoms period, transmitted through the Chinese commandery at Lelang, which ruled the northwest of the peninsula in 108 BC–AD 313. The spread of the Buddhist faith eastwards into Korea in the 4th to 6th centuries brought the need to provide copies of holy writings, required by monks and believers for their devotions and studies. Sponsors supported hand-copying and, later, printing of scriptures; the names of such benefactors are sometimes recorded in colophons or other notes to the texts. During the Three Kingdoms, United Silla, and Koryŏ (918–1392) periods, all such copies were in Chinese characters, since classical Chinese was accepted as the written language of palace, court, and temple. Finely produced temple copies of such texts as the Diamond and Lotus Sutras, stamped images of the Buddha, and copies of incantations and chants were certainly produced in great numbers, although few have survived from before the Koryŏ.

The printed text of the Mugu chŏnggwang tae taranigyŏng, (Pure Light Dharani Sutra), a kind of Buddhist incantation, was discovered in October 1966 in the second storey of the Sŏkkat’ap (Sakyamuni Pagoda) at Pulguksa (Pulguk Temple), Kyŏngju. This text was translated into Chinese in 704, and the temple built in 751; thus, the Dharani was printed and then enclosed inside the pagoda, probably to mark the temple’s consecration. This small paper scroll, measuring 6.5 × 648 cm, was found in a container for Buddhist relics. Its measurements are approximate, since the early sections are in a poor state of conservation. Each of its twelve sheets of paper contains between 55 and 63 columns of characters; each column has seven to nine characters, measuring 4–5 mm. It was printed on thin mulberry (Korean tak) paper from engraved wooden blocks. On the basis of analysis of the graphic style of the characters and the vegetable material used for the paper (broussonetia kazinoki), it seems that the Silla kingdom was its probable place of production. The text uses Empress Wu characters, special graphic forms for a small number of terms created in China during her rule (684–705). Given the extent of cultural exchange between Tang China and Silla, it is entirely credible that a text originally cut on to blocks and printed in China could have been re-cut and printed in Korea, to be buried as part of a group of protective holy relics during the consecration of Pulguk Temple.

Another example of the highly developed nature of textual transmission in the Silla period is a fine scroll MS of chapters 1–10 of the Avatamsaka Sutra in the Ho-Am Museum (National Treasure 196 of the Republic of Korea). This document was copied in 754–5 at the behest of High Priest Yŏn’gi Pŏpsa of Hwangnyong Temple, Kyŏngju. The colophon records the date of production, as well as the names and ranks of the nineteen workers who made the copy. They include the sutra copyists, the painter of the cover papers, and the paper-makers. The text, in regular sutra-script, is enclosed in a cover of purple-dyed mulberry paper, on which two Bodhisattvas seated in front of a storied, tiled-roof building have been painted in gold. Measuring 14 metres long and 26 cm high, with 34 characters per column, the scroll is composed of 43 sheets of sheer white paper and is rolled around a 24-cm wooden spindle with crystal knobs on both ends.

Woodblock printing of Buddhist texts grew in volume and extent throughout the period of Koryŏ rule, a time of intense devotion to the Buddhist faith. The Korean printing historian Sohn Pow-Key has estimated that more than 300,000 woodblocks for the texts of Buddhist scriptures were cut. The act of sponsoring sutra-copying was believed to gain spiritual merit for the believer.

Pre-eminent among the printing enterprises of the period were the two sets of woodblocks engraved to print the entire known corpus of Buddhist scriptures, the Tripitaka. In both instances, the enterprise was motivated as much by a desire to secure divine protection for the nation against the succession of continental invaders who attacked it—the Khitan in the 11th century, the Jurchen (founders of the Jin dynasty in China) in the 12th century, and the Mongols in the 13th century—as by a pious concern to preserve and record its sacred sermons, Buddhist rules, and treatises. Mindful of the need for divine protection, the court commissioned artisans to select and prepare wood, to copy the carefully chosen and checked texts, to cut the transferred texts in relief on both sides of the blocks, and then to print, using charcoal-based inks, on to locally produced paper.

The Tripitaka was first cut in Korea for printing in its entirety, over a long period between 1011 and 1087; however, the blocks were lost, destroyed by fire during the Mongol invasions of the early 13th century. About 300 printed Tripitaka scrolls (out of some 11,000) survive in the Buddhist temple Nanzenji, Kyoto. Volume 78 of the Avatamsaka Sutra from the same Tripitaka is in the Ho-Am Art Museum (National Treasure 267 of the Republic of Korea). The monk Ŭich’ŏn (1055–1101), fourth son of King Munjong, had travelled to China and collected thousands of Buddhist texts to bring to his native country. He devoted many years to cataloguing the teachings of the different Buddhist schools, and compiled the Sok changgyŏng (Supplement to the Canon).

Immediately after the first Korean Tripitaka was lost, the enterprise of cutting a new Tripitaka was undertaken. This re-cut Tripitaka was a project of the highest importance for king and country, the work lasting from 1236 to 1251. The exact number of blocks, made of seasoned woods, has been estimated differently by various scholars. Currently, 81,155 blocks survive: eighteen of the original blocks were lost, 296 were added in the Chosŏn period (1392–1910), and twelve were added during the Japanese occupation (1910–45). The number of blocks has given the name ‘P’almangyŏng’ (Tripitaka of 80,000) to the 13th-century Tripitaka. The blocks measure 72.6 × 26.4 × 3 cm and are engraved on both sides. The print area, delineated by single-line borders, is 24.5 cm high, and each block has 23 columns of fourteen 27-mm-high characters. The graphic style of the characters is uniform throughout the entire corpus. Each block carries the name of the sutra, the chapter and the folio number. The blocks have been lacquered, and metal reinforcing strips have been applied to the corners to prevent warping. On completion of cutting in 1251, the blocks were used for printing at Namhae, South Kyŏngsang province, and subsequently moved north for storage to a repository on Kanghwa Island.

At the time of the second cutting of the Tripitaka blocks, between 1236 and 1251, the Koryŏ court had fled from the invading Mongols, to take refuge on Kanghwa Island. By the late 14th century, however, even Kanghwa Island was no longer secure against hostile forces. Pirate attacks endangered the security of the scriptures, and there was military unrest throughout the country. This led to the choice of the distant southern mountain fastness of the Haeinsa Buddhist temple as a safe storage location for the precious double-sided printing blocks, which were moved there in 1398. In 1488, decades after the blocks had arrived at Haeinsa, a set of four special buildings was repaired and adapted to protect the blocks. Located higher than the rest of the temple complex, these structures are rectangular wooden-pillared, hipped-roof buildings, set on granite stones, and arranged in a courtyard formation. Rows of slatted windows punctuate the walls, providing natural ventilation and minimizing the spread of damp. The earthen floors of the stores lie on a layer of charcoal, regulating humidity and temperature, and exposed rafters encourage air circulation. The woodblocks are arranged on five-storey shelf structures. Rare survivals of the wooden architecture of the early Chosŏn dynasty, the repositories have proved a well-ventilated and damp-proof environment to safeguard the precious blocks. Between 1967 and 1976, a set of impressions of the Korean Tripitaka was made from these blocks and distributed to libraries and universities in Korea and around the world.

Looking more broadly at book production in Koryŏ, it is notable that scholars and officials paid increasing attention to the teachings of the Chinese philosopher Confucius, and thus required copies of definitive versions of Confucian texts and commentaries by later Chinese scholars. Obtaining books from China was often difficult, because of war or because the Chinese authorities were suspicious of Korea’s reasons for seeking copies of Chinese books. Indeed, the Song poet Su Dongpo (1036–1101) wrote several times against the sending of books to Koryŏ. The Korean court was often frustrated in attempts to obtain the goods it needed from China. Gifts of books were sent only with imperial consent, which could not be relied upon. Despite these difficulties, Korean book collecting was so persistent that on three or four occasions during the 10th and 11th centuries, Koryŏ sent back Chinese books that had been lost in Song China and were required there. The Chinese envoy Xu Jing, who visited Korea in 1123, noted in his account of the visit, Xuanhe fengshi Gaoli tujing (Illustrated Account of the Xuanhe Emperor’s Envoy to Korea), that the ‘Royal Library by the riverside stores tens of thousands of books’ (Sohn, ‘Early Korean Printing’, 98).

During the 13th century, experiments with movable type produced works that have since been lost, but are remembered because of the practice of recording printing information in colophons. From this period, three pieces of evidence survive for the use of movable metal type. One is a collection of Buddhist sermons entitled Nanmyŏng ch’ŏn hwasang song chŭngdoga, printed on Kanghwa Island in 1239 using blocks cut from a text originally printed using cast movable types. The colophon states:

It is impossible to advance to the core of Buddhism without having understood this book. Is it possible for this book to go out of print? Therefore we employ workmen to re-cut the cast-type edition to continue its circulation. Postface written with reverence by Ch’oe I [d. 1249] in the 9th moon [of 1239].

The second piece of evidence for 13th-century movable-type printing is a collection of ritual texts, Sangjong yemun, which were reprinted c.1234 during the Kanghwa Island period, using metal types, to replace an original lost during the flight from Kaesŏng. The colophon clearly states, ‘here we have now printed 28 copies of the book with the use of movable metal types, to distribute among the various government offices’; it then expresses the hope that officials will not lose it. The third piece of evidence is a number of excavated individual types from the Koryŏ era, now in Korean museum collections. These types have a metallic composition similar to that of Koryŏ coins. An example is the 1 cm-high character for ‘return’ (pok), now in the National Museum of Korea. Scholars believe that the disruptions of the mid-Koryŏ, when the court moved from Kaesŏng to Kanghwa, stimulated the use of metal types, in order to produce small editions of essential works destroyed during the Mongol invasions. Clearly, Koryŏ printers made significant use of movable type in the mid-13th century.

No dated work printed with movable types survives from the 13th century. For the 14th century, however there is an extant work—the world’s earliest—printed by means of metal movable types. Paegun hwasang ch’orok pulcho Chikchi simch’e yojŏl (Essentials of Buddha’s Teachings Recorded by the Monk Paegun) is a collection of Buddhist biographical and historical excerpts by the Sŏn (Zen) Buddhist master Kyŏnghan (1298–1374), better recognized by his pen name of Paegun. Also known as Chikchi simch’e yojŏl, it consisted of two volumes: the lost first volume comprised hymns and poems, and teachings of Buddhist masters; the incomplete second volume is held by the Bibliothèque nationale de France. The surviving volume bears a colophon dating it to the seventh moon of 1377; it notes that the place of production where movable type was used was Hŭngdŏksa, a temple in Ch’ŏngju. The verso of the colophon sheet records the names of two Buddhist believers in charge of printing, Sŏkchan and Taldam, as well as a sponsor, the nun Myodŏk. The volume contains 38 sheets, with a print area of 20.2 × 14.3 cm. There are eleven columns of 18–20 characters. Formerly in the collection of the French diplomat Collin de Plancy (1853–1922), the book was recorded by Courant in Bibliographie coréenne (no. 3738) before disappearing from view; it reappeared in a 1972 exhibition in Paris. Hŭngdŏksa was excavated in 1984 during the construction of a housing development, revealing bronze vessels bearing the temple name. Subsequently, the Cheongju (Ch’ŏngju) Early Printing Museum was opened at the temple site to celebrate Korea’s contribution to printing and to mark the place of production of this, the world’s earliest surviving book printed with metal movable type.

The world’s earliest dated printing using movable type, Paegun hwasang ch’orok pulcho Chikchi simch’e yojŏl (Essentials of Buddha’s Teachings Recorded by the Monk Paegun), printed at Hŭngdŏksa (Ch’ŏngju) in 1377. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des Manuscrits (division orientale) (Koreana 7, no. 2)

To understand the reasons for the adoption of movable type as a method of printing in Korea, it is useful to think of the disadvantages of woodblock printing in a society where the need for books was confined to a small readership. Cutting wooden blocks is relatively wasteful of materials, and requires that the blocks be stored for reuse, with the ever-present danger of destruction through fire. It is striking that evidence of 13th-century metal movable type dates to the period of the Mongol invasions, when fire destroyed countless buildings and their contents. In China, by contrast, print runs were much larger than the tens of copies normal in Korea; thus, there was little incentive to popularize the use of movable type, because blocks could be used to make dozens of impressions. Sohn has pointed out that, in Korea,

works printed with metal type were printed in relatively small quantities and include a wide variety of titles. On the other hand, works in great demand, such as calendars, were printed from woodblocks. (Sohn, ‘King Sejong’s Innovations’, 54)

A further consideration must be the availability of raw materials and of skilled metal-working artisans engaged by the foundries of Buddhist temples, which commissioned bronze bells, drums, and utensils for temple services.

In 1392, after a period of instability and Mongol-dominated rule earlier in the century, the new dynastic house of Chosŏn came to power and established its capital in the centre of the peninsula, in modern-day Seoul. It continued to patronize Confucian studies in an increasingly systematic fashion. The period of Buddhist predominance drew to a conclusion. Indigenous customs and practices had long coexisted with those of the imported religion, but Confucian rites and practices began to exert an ever-stronger influence on family and ritual life. Confucian ideals gradually penetrated beyond the court and aristocratic class. Confucian studies were not an innovation of the Chosŏn period—they had formed the syllabus of the state examinations introduced in Koryŏ in the 10th century—but the early Chosŏn kings and their advisers began to reform social and religious observances and to sweep away heterodox ideas and practices, both those of native Korean origin and the excessive powers of the Buddhist Church. For this, they needed to study many Chinese editions of works of neo-Confucian philosophy. Chosŏn rulers and officials may have known of printing using metal types in Koryŏ times. In the early years of the 15th century, they began attempts to make the technique more efficient.

The third Chosŏn king, T’aejong (r. 1400–1418), is recorded as showing great concern about how books were produced:

Because our country is located east of China beyond the sea, not many books from China are readily available. Moreover, woodblock imprints are easily defaced, and it is impossible to print all the books in the world using the woodblock method. It is my desire to cast bronze type so that we can print as many books as possible and have them made available widely. This will truly bring infinite benefit to us. (Lee, i. 537)

The types cast at T’aejong’s behest, known from the cyclical name of the year 1403 as kyemi, were the first of a series of cast types—almost all made of bronze, but including a number of iron, lead, and even zinc types—produced throughout the long rule of the Chosŏn house.

After the 1403 fount, the next casting was in 1420, the kyŏngja year. Again, the dynastic annals provide a detailed account of royal involvement, in the person of the fourth king, Sejong (r. 1418–50):

To print books, type used to be placed on copper plates, molten beeswax would be poured on the plates to solidify the type alignments and thereafter a print was made. This required an excessive amount of beeswax and allowed printing of only a few sheets a day. Whereupon His Majesty personally directed the work and ordered Yi Ch’ŏn and Nam Kŭp to improve the casting of copper plates to match the shape of the type. With this improvement the type remained firmly on the plates without using beeswax and the print became more square and correct. It allowed the printing of several sheets in a day. Mindful of the Typecasting Foundry’s hard and meritorious work, His Majesty granted wine and food on several occasions. (Lee, i. 538)

The resulting page was well proportioned, with characters whose horizontals slope slightly upwards from left to right. This flat-heeled type could be evenly spaced without wax; it represents an important refinement of the use of movable type.

Sŏng Hyŏn (1439–1504) described the processes involved in printing with metal types in Yongjae ch’onghwa (Assorted Writing):

The person who engraves on wood is called the engraver and the person who casts is called the casting artisan. The finished graphs are stored in boxes and the person responsible for storing type is called the typekeeper. These men were selected from the young servants working in the government. A person who reads manuscript is called the manuscript reader. These people are all literate. The typekeeper lines up the graphs on the manuscript papers and then places them on a plate called the upper plate. The graph levelling artisan fills in all the empty spaces between type on the upper plate with bamboo and torn cloth, and tightens it so that the type cannot be moved. The plate is then handed over to the printing artisan to print. The entire process of printing is supervised by members of the office of editorial review selected from among graduates of the civil service examination. At first no-one knew how to tighten up the type on a printing plate, and beeswax was used to fix type on the plate. As a result each logograph had an awl-like tail, as in the kyŏngja type. Only after the technique of filling empty space with bamboo was developed was there no longer a need to use wax. Boundless indeed is the ingenuity of men’s intelligence.

In 1434, the type known as kabin was cast, and enjoyed such popularity that it was recast seven times over hundreds of years. It is a large fount, with characters measuring 14 × 15 mm (compared to 10 × 11 mm for the 1420 fount), and an elegant and lively calligraphic style. This type is narrower at the base than on the printing surface, and was therefore economical to cast. Kabin types for Chinese characters were also used in the first work to be printed using both Chinese characters and Korean han’gŭl movable types: the Sŏkpo sangjŏl (Episodes from the Life of the Buddha) printed in 1449 from a 1447 fount. Han’gŭl, an invented syllabic script, was introduced by King Sejong in 1443 to increase the literacy of the population and to represent the sounds of Korean graphically. In the preface to Hunmin chŏngŭm (Correct Sounds to Instruct the People), Sejong wrote:

The sounds of our language differ from those of Chinese and are not easily communicated by using Chinese graphs. Many among the ignorant, therefore, though they wish to express their sentiments in writing, have been unable to communicate. Considering this situation with compassion, I have newly devised twenty-eight letters. I wish only that the people will learn them easily and use them conveniently in their daily life.

The new alphabet was the culmination of years of research by King Sejong and his scholar assistants. The letterforms have a fascinating origin. Consonants are shown in shapes mirroring the position of oral organs during articulation of each sound: the ‘k’ sound being shown by ¬, reflecting the position of the tongue against the roof of the mouth, while the ‘m’ sound, a square shape, □, imitates pursed lips in forming the sound. Closed vowels are represented graphically using horizontals, and open vowels using vertical lines. The Korean alphabet has always been written syllabically, with groups of letters arranged in discrete squares rather than in long strings, reflecting the phonemic structure of the language. This grouping convention is clearly influenced by the appearance of written Chinese characters. The earliest han’gŭl letters, in the 15th and 16th centuries, were upright and angular, but with time the practice of brush writing engendered a more fluent style incorporating curved and weighted strokes. The first publications to reproduce han’gŭl were produced from woodblocks, but in the centuries that followed, many works were published using types; Sohn listed fourteen han’gŭl founts in his 1982 survey of Korean types, Early Korean Typography.

The finest editions continued to be court-sponsored works, supervised by the Office of Paper Production, the Office of Movable Type, and the Office for Woodblock Printing. By the late Chosŏn, private individuals, Confucian academies (sŏwŏn), local scholars, and authors all sponsored the printing of books, and some commissioned new types.

Despite the close interest of 15th-century Korean kings in printing technology, the early introduction of cast metal-type printing led neither to an expansion of publishing nor to demonstrable increases in literacy. The reasons for this lie in the Confucian values that dominated society. With a strong focus on self-cultivation and virtuous leadership, the government encouraged austerity and deplored commerce. According to Confucius, the ideal man should be ‘poor yet delighting in the Way, wealthy yet observant of the rites’ (Analects, i.15). Korean scholar-officials of the Chosŏn fervently upheld this Confucian ideal, depressing the natural growth of markets and the circulation of traded goods. In this restrictive economy, books were printed for use in tightly controlled circumstances. Technical manuals, children’s textbooks, lists of medical plants, maps, collections of letters, language primers, and practical and literary works were available to the officials, teachers, and artisans who required them. Gazetteers recorded the topography, products, population, and significant achievements of the various regions of the land. For lower-class people, and for teachers in schools in different regions of the country, popular and philosophical works were produced to promote the Confucian virtues of loyalty, obedience, chastity, brotherly love, and filial piety. Clan associations issued detailed genealogies to allow each generation to trace its family lineage, an important component of Confucian ancestor worship. Candidates for the civil service examinations studied the philosophical and literary texts that formed the syllabus of these gruelling, extended tests.

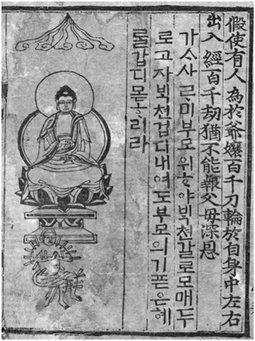

Han’gŭl script from the Sutra of Filial Piety in a 16th-century block printing copy. © The British Library Board. All Rights Reserved (Or. 74.b.3)

Despite the restrictive nature of the economy and government control of print, then, tens of thousands of hand-copied and printed books from Koryŏ and Chosŏn times survive in Korean and overseas libraries. The Harvard-Yenching Library catalogue alone lists 3,850 titles. Libraries in Japan contain substantial holdings of rare Korean books. Despite the losses caused by time and by war, the national and former royal libraries in South Korea preserve vast repositories of archival and published material, periodically enriched by donations from private collections. Book reading and scholarship were a vital part of Korean life.

With the advent of Japanese and Western political and economic interests c.1880, modern printing technology was introduced. The Hansŏng Sunbo/Seoul News was printed using a Western-style press imported from Japan, associating new technology with the reform movement that flourished briefly in the face of strong conservative opposition from the political elite. Christian missionaries were important carriers of printing innovation to Korea (see 9): the Trilingual Press was established in 1885 by a Methodist, H. G. Appenzeller. French Catholics were also active in the late 19th century, and Father E. J. G. Coste supervised the printing and binding of the pioneering Dictionnaire coréen in 1880, introducing the first han’gŭl founts used by non-Korean printers. Bibles and language-learning aids were among the early publications of the first English press, which printed James Scott’s English and Corean Dictionary under the supervision of Bishop C. J. Corfe in 1891. The Pilgrim’s Progress, Aesop’s Fables, and Gulliver’s Travels were other early Western titles published by missionaries in this period.

Japan annexed Korea in 1910, leading to a decline in independent publishing. The period 1910–45 was characterized by some cultural enterprises forcefully resisting the Japanese colonial regime, while others accommodated and collaborated with the Japanese. Writing and publishing in the Korean language was constrained, as the colonizers attempted to shape Korean social and cultural identity in ways that supported Japanese imperialist ambitions. For a time, the future of Korean as a medium of formal communication and education was uncertain. It was against this background of struggle and contested nationhood that modern Korea’s influential newspaper and book publishing companies were founded. Writers, academic societies, and newspapers all had to contend with military control and close censorship. Resentment against Japan continues to colour both of the modern Korean states’ commercial and official publishing enterprises.

Following Japan’s defeat in 1945 and the Korean War of 1950–53, the peninsula was divided into a communist north and a capitalist south. Since then, the Korean book has had two principal manifestations, which naturally reflect the separate social systems, market models, and graphic identities of North and South Korea. South Korean books have used a mixed script, with a small number of Chinese characters, particularly for place and personal names. The publishing industry, both academic and commercial, is highly developed and integrated into the international community. Bookshops thrive in the major cities. In addition to print publishing, South Korea has become a world leader since the 1990s in electronic publishing and database creation. Digitized versions of the Korean Tripitaka and the Annals of the Chosŏn Dynasty are pioneering examples of large-scale scholarly digital projects that have revolutionized access to pre-modern textual sources in the humanities (see 21).

North Korean publishing is dominated by Communist Party doctrine and the cult of the late President Kim Il Sŏng (1912–94) and his son and successor, Kim Jŏng Il (1942–2011). The quality, circulation, and appearance of North Korean publishing in the early 21st century has changed little since the economic crisis that followed the collapse of the international socialist bloc in 1989. Book circulation in North Korea is low, and subject-matter tightly controlled by the state. Nevertheless, a steady stream of fiction, poetry, historical studies, reference books, sheet music, cartoons, and educational textbooks is produced. In contrast to the South Korean practice of mixed Chinese and han’gŭl script, in North Korea, no Chinese characters are used. There is very little interaction with publishing outside the country; electronic publishing is closely controlled. Generally, North Korean institutions and individuals are not connected to the World Wide Web. Despite these differences, however, the two Koreas are united by their pride in the 15th-century han’gŭl alphabet. They also celebrate Korea’s notable achievements in printing culture: the world’s earliest datable printed text (c.751); the earliest dated work printed with movable type (1377); and the survival of the Korean Tripitaka woodblocks stored at Haeinsa (13th century).

M. Courant, Bibliographie coréenne (3 vols, 1894–1901)

P. Lee, ed., Sourcebook of Korean Civilization (2 vols, 1993–6)

B. Park, Korean Printing (2003)

Sohn Pow-Key, ‘Early Korean Printing’, Journal of the American Oriental Society, 79 (1959), 96–103

—— Early Korean Printing (1984)

—— ‘King Sejong’s Innovations in Printing’, in King Sejong the Great, ed. Y.-K. Kim-Renaud (1992)

—— ‘Invention of the Movable Metal-type Printing in Koryo: Its Role and Impact on Human Cultural Progress’, GJ 73 (1998), 25–30