Missionary Printing

M. ANTONI J. ÜÇERLER, S.J.

The history of printing and the history of the book would be incomplete without an understanding of the key role played by printing presses that were established by missionaries, Roman Catholic and Protestant, in countries throughout East and Southeast Asia, Oceania (see 46, 47), Africa (see 39), the Middle East (see 40), and the Americas (see 48, 49, 50, 51). The missionaries soon discovered that both the propagation of Christian doctrine and the inculcation of its ethical precepts could be greatly aided by the mass production and distribution of books and pamphlets. The earliest missionary presses were established in the 16th and 17th centuries and were linked for the most part to the Roman Catholic religious orders—Franciscans, Dominicans, Augustinians, and Jesuits—that were engaged in activities throughout the New World and Asia.

Protestant missionary presses first appeared on the Asian scene in India in the 17th century. Over the following 100 years, foundations such as the London Missionary Society, the British and Foreign Bible Society (BFBS), and the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions were established on both sides of the Atlantic. A common characteristic of their method of evangelization was the strategic use of the printing press.

Missionary printing has taken place throughout the world from the 16th century onwards. This essay provides a preliminary sketch of the most significant developments in South, Southeast, and East Asia: for the Americas, see 48, 49, 50, and 51.

The story of missionary presses begins on the west coast of India 46 years after the Portuguese first conquered and established a strategic commercial entrepôt in the port city of Goa in 1510. João Nunes Barreto, the patriarch designate of Ethiopia, brought a printing press from Portugal to Goa on 6 September 1556. This press was originally destined for use in Africa, but in view of strained relations between the missionaries and the Emperor of Abyssinia, it remained in Goa. One of the Jesuits who accompanied Barreto to India was Juan de Bustamente (also known from the 1560s as João Rodrigues), who became master printer at the Jesuit College of St Paul. The press was first used on 19 October 1556, when lists of theses (conclusões) in logic and philosophy were printed as broadsides for students of the College to defend publicly (Wicki, iii. 514, 574). The following year saw the publication of the first book, a compendium of Christian doctrine, composed several years before by Francis Xavier for the catechesis of local children.

Juan Gonsalves (or Gonçálvez), another Spanish Jesuit, is credited with having produced in Goa, in 1577, the earliest metal type in Tamil. Pero Luis, a Brahmin and the first Indian Jesuit, and João de Faria, who helped to improve the fount, assisted Gonsalves. The result was the first book printed with movable type in an Indian language, namely an emended version of Xavier’s original Tamil catechism, revised by Henrique Henriques, who was the first systematic lexicographer of the language. The 16-page booklet was produced in Quilon (Kollam) in 1578. The colophon on the last page includes text printed from the type made in Goa the previous year. Another catechism (Doutrina christã) by Marcos Jorge, originally published in Lisbon in 1561 and 1566, was translated into Tamil and printed with Faria’s type in Cochin on 14 November 1579 (Shaw, ‘“Lost” Work’, 27). A guide to how to make one’s confession (Confessionairo) and a collection of the lives of the saints (Flos Sanctorum) in Tamil followed in 1580 and 1586 respectively. All these books were prepared in accordance with instructions issued in 1575 by Alessandro Valignano, who was responsible for all Jesuit missions in Southeast and East Asia between 1573 and 1606 (Wicki, x. 269, 334). He would also play a crucial role in the beginnings of missionary printing in China and Japan.

The first publication in an Indian language other than Tamil was printed in Konkani some time before 1561 at the College of St Paul. In a letter from Goa on 1 December 1561, Luís Fróis reports that a printed summary of Christian doctrine was read to the local people ‘in their own language’ (Wicki, v. 273; Saldanha, 7–9). No copy of this work (probably a small booklet) is known to have survived. There are copies, however, of the books written by Thomas Stephens, an English Jesuit and pioneer in the study of Indian languages. The first was his ‘Story of Christ’ (Krista purāna) in literary Marathi, printed in 1616, 1649, and 1654. The second work was a Christian doctrine (Doutrina christam em lingoa bramana canarim) in Konkani, the language spoken by the Brahmins in Goa; it was printed posthumously in 1622 (Priolkar, 17–18). Stephens also composed the first missionary printing grammar of Konkani, which came off the press in 1640. Although the missionaries had made attempts to produce Indian type in Marathi-Devanāgarī script or ‘lengoa canarina’ as early as 1577, they gave up their efforts on account of the difficulty of producing so many matrices. As a result, they printed Stephens’s works in Roman transliteration only (Wicki, x. 1006–7). A total of 37 titles in Portuguese, Latin, Marathi, Konkani, and Chinese were printed between 1556 and 1674 (Boxer, 1–19). The promulgation of a decree in 1684 by the Portuguese authorities in Goa banning the use of Konkani, in a move to root out all local languages, brought Roman Catholic missionary printing in India to an abrupt end. Two centuries would pass before it could be revived.

Meanwhile Bartholomew Ziegenbalg, a Lutheran from Germany and the first Protestant missionary in India, travelled in 1706 to the Danish East India Company’s coastal mission at Tranquebar (Tharangambadi), north of Nagappattinam, where he soon became proficient in Tamil. A library of Jesuit publications, including Henriques’ grammar, was available to Ziegenbalg, who found them useful in avoiding pitfalls in the translation of his own works. He wrote to Denmark requesting a printing press in 1709. His Danish patrons then appealed to the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge in London, which shipped a press to India in 1712. On 17 October of that year, a Christian doctrine in Portuguese and Tamil was printed in roman letters. Many other works followed and were printed with Tamil type, which he arranged to be cast in Germany on the basis of drawings he had prepared. The type was produced at Halle in Saxony and sent to India in 1713 with Johann Gottlieb Adler, a German printer who established a type foundry in Porayur just outside Tranquebar. Ziegenbalg’s translation of the New Testament into Tamil was printed in two parts (1714–15) with a new smaller typeface cast by Adler. A second edition followed in 1724, with further editions in 1758, 1788, and 1810 (Rosenkilde, 186). To counter the constant shortage of paper and ink, Ziegenbalg also helped establish a local paper mill and a factory to produce ink.

After Ziegenbalg, the most famous Protestant missionary printer in India was William Carey, who founded the Baptist Missionary Society in 1792 and arrived in West Bengal the following year. In 1800, he succeeded in establishing a missionary press at Serampore (Shrirampur), a Danish settlement 20 km north of Calcutta (Kolkata), which was supervised by his fellow missionary and printer, William Ward. Carey then published the Gospel of Matthew, the earliest imprint produced with Bengali type. The following year saw his first complete translation of the New Testament in that language. Working with his fellow missionary, Joshua Marshman, and with learned Indian converts, he produced further translations of the Bible into Sanskrit, Hindi, Oriya, Marathi, Assamese, and many other languages. The Serampore press, in operation until 1855, became the most prolific Christian printing concern in India, producing works in more than 40 different languages and dialects (see 41).

The Chinese stage on which missionaries made their appearance in the 16th century was very different from that of India. Most significant was the integrity of China’s territory, free from any form of colonial coercion that might include foreign attempts to control or censor the printed word. Although records show evidence of the use of movable type made from an amalgam of clay and glue as early as the 11th century, the technology that dominated the Chinese world of printing until the 19th century remained xylography or woodblock printing, first employed in China around AD 220 (see 42). The bureaucracy of the Middle Kingdom, which was based on a highly centralized civil service examination, depended on the ready availability and wide distribution of books. This in turn created the need for thousands of printers and bookshops throughout the realm. Thus, when Michele Ruggieri and Matteo Ricci, the first two Italian Jesuit missionaries to compose works in literary Chinese, wished to have their books published, they turned to their friends among the literati, who made arrangements to have the printing done either in their own private printing office or by another local printer.

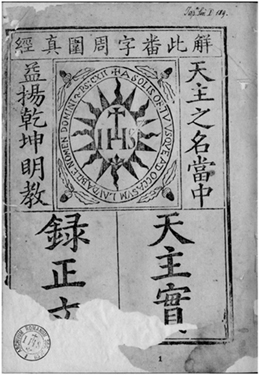

In a way similar to their counterparts in India, the missionaries in China concentrated their early efforts on producing summaries of Christian doctrine. In 1584, they succeeded in printing at Zhaoqing Ruggieri’s Tianzhu shilu (The True Record of the Lord of Heaven), the earliest translation of a catechism into Chinese.

Jesuit printing in China: Michele Ruggieri’s Tianzhu shilu (The True Record of the Lord of Heaven), printed at Zhaoqing in 1584. © Institutum Historicum Societatis Iesu (Rome).

The Tianzhu shiyi (The True Meaning of the Lord of Heaven), a completely revised catechism in dialogue form, was composed by Matteo Ricci and printed in Peking (Beijing) for the first time in 1603. These catechisms, which encompassed a wide range of genres, mark the beginning of the prolific production of works composed in Chinese by several generations of missionaries and printed throughout China on private presses and at printing offices using woodblocks. In addition to expositions of Christian doctrine and liturgical texts, there were works introducing adaptations of Western classical books in the humanities—especially in moral philosophy—as well as numerous scientific treatises on astronomy, mathematics, physics, and geography. In this enterprise the foreign missionaries were often aided by erudite Chinese converts, the most prominent of whom were Xu Guangqi, Yang Tingyun, and Li Zhizao. Approximately 470 works on religious and moral topics composed by missionaries in China and Chinese Christians were printed between 1584 and 1700. Another 120 titles dealt with the West and science (Standaert, 600). These books represent an extraordinary bridge between the canons of classical literature in China and Europe, and they provide both the East and the West with a literary window into each other’s ancient cultures and traditions.

The first Protestant missionary in China was Robert Morrison, who arrived in Canton (Guangzhou) in 1807 as a member of the London Missionary Society (LMS). Together with his fellow missionary, William Milne, he subsequently founded the Anglo-Chinese (Yingwa) College in the ‘Ultra-Ganges Mission’ in Malacca (Melaka) in 1818 and completed a translation of the Bible into Chinese in 1819 (printed in 1823). The mission press of the LMS, however, began operations in Malacca as early as 1815. Among the early imprints of 1817 are ‘The Ten Commandments’ and ‘The Lord’s Prayer’ in Malay, produced in Arabic-Jawi script (Rony, 129). From Malacca, Milne sent Thomas Beighton in 1819 to establish a school for the education of Malays and Chinese in Penang and to work as a printer. Samuel Dyer, Morrison’s former student and also an LMS member, arrived in Penang in 1827. An expert in punchcutting, he worked on a new steel typeface for Chinese characters.

In Singapore, the BFBS had been printing works in Malay since 1822, just three years after Sir Stamford Raffles founded the free trading post. There were also other mission presses that produced a variety of imprints in the 1830s and 1840s and were administered by the LMS and the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM). Two men deserve special mention in this regard. The first is Benjamin Peach Keasberry, a pioneer in Malay education who had perfected his printing skills at Batavia (Java). He learned the language from Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir (or Munshi Abdullah), the father of modern Malay literature, who helped him to produce a new translation of the New Testament into Malay (after the earlier partial Amsterdam and Oxford editions of 1651 and 1677). The second was Alfred North, a Presbyterian minister from Exeter, NH, who was head of the printing division until 1843, the year the American Mission in Singapore was closed. When the 1842 Treaty of Nanking allowed the British to take up residence in China, Walter Henry Medhurst established a new LMS Press in Shanghai, which soon became the most prolific in modern China, printing works in English, Chinese, and Malay on a wide range of topics, sacred and secular. An accomplished polyglot and pioneer lexicographer, Medhurst also published numerous dictionaries, including the first English–Japanese, Japanese–English vocabulary, printed in Batavia in 1830.

Dominican missionaries, who would lead early missionary printing in the Philippine archipelago, built their church and convent of San Gabriel among the Chinese merchants in the Parián, or market district of Manila after their arrival in 1587. The missionaries soon set about preparing Christian texts for the native Filipino as well as the mixed Chinese (or sangley) populations. A number of catechisms circulated in MS as early as the 1580s. Some time before 20 June 1593, Gómez Pérez Dasmariñas (governor, 1590–93) authorized the printing of two Christian doctrines, one in Spanish and Tagalog, and another in Chinese. The Tagalog text was prepared by the Franciscans working under Juan de Plasencia, whereas the Chinese doctrine was composed by the Dominicans supervised by Juan Cobo. Both were printed with woodblocks prepared by a Chinese convert and printer, Geng Yong (or Keng Yong), whose Spanish name was Juan de Vera. Cobo composed another summary of Christian doctrine along with a synopsis of Western natural sciences (Shilu), which was printed posthumously in 1593. It is noteworthy that Cobo mentions having read Ruggieri’s printed catechism of 1584 (Wolf, 37).

Other devotional works followed in movable type between 1602 and 1640 from the Binondo (or Binondoc) quarter of Manila. Of these, the first imprint was probably a booklet with the mysteries of the rosary, printed in 1602, composed by a Dominican, Francisco Blancas de San José, who set up the press at the convent. This was followed by a pamphlet containing the ordinances of the Dominican Order in the Philippines (Ordinationes Generales) and another treatise by Blancas de San José, entitled Libro de las quatro postrimerías del hombre en lengua tagala, y letra española. Both were printed by Juan de Vera in 1604–5. Other works, printed by de Vera’s brother, Pedro, began to appear in 1606. He printed a grammar, Arte y reglas de la lengua tagala (1610), compiled by Blancas de San José, and a book in Tagalog to teach the native population Spanish. Pedro de Vera printed these works in Abucay, part of Bataan province where Tomas Pinpin and Domingo Laog, regarded as the first native Filipino typesetters and printers, were active for several decades. The Franciscans also had a press as early as 1606, but no evidence remains of its productions prior to 1655, after which it was transferred to Tayabas (Quezon) in 1702 and to Manila in 1705. The Jesuits, on the other hand, established a press in 1610 at their college in Manila, and the Augustinians were printing at their own convent in Manila as early as 1618. Thus, several hundred titles were published at missionary presses in the Philippines before the 19th century.

The story of missionary printing in Japan is linked to Alessandro Valignano, who was also instrumental in early printing in India. The Jesuits, who first landed in Japan in 1549, soon realized the need for books in order to carry out their work, especially among the learned elites. Unlike China, Japan during the so-called era of Warring States (1467–1568) did not provide them with a readily accessible network of printers on whom they could rely. Valignano therefore instructed Diogo de Mesquita, a Portuguese Jesuit, to procure a press in Europe and to have Japanese typefaces cut in Portugal or in Flanders. The press was acquired in Lisbon in 1586 and first used to print a small booklet, Oratio Habita à Fara D. Martino, in 1588 in Goa. There, a number of young Japanese, including Constantino Dourado and Jorge de Loyola, learned punchcutting from Bustamente, the master printer at the College of St Paul. The press was employed again later that year in Macao to print Christiani Pueri Institutio, a popular treatise in Latin by Juan Bonifacio, before it reached its destination further east.

The first imprints of the new Jesuit mission press were prepared at their college at Kazusa in 1590–91 and included summaries of Christian doctrine, broadsides with prayers, and an abridged version of saints’ lives (Sanctos no gosagueo no uchi nuqigaqi). This last work was the first book printed in Japanese with movable type. These early imprints employed roman script with a few unsuccessful attempts to produce Japanese type. Other works printed with roman type include the Feiqe no monogatari (Tale of the Heike) (1592), a translation of Aesop’s Fables (Esopo no fabulas) (1593), as well as the trilingual Latin–Portuguese–Japanese dictionary of 1595. A Japanese–Portuguese dictionary (Vocabulario da lingoa de Japam) and the first grammar of Japanese (Arte da lingoa de Japam) were printed between 1603 and 1608. Major improvements to the wooden type were made in the early 1590s; metal type of high quality in cursive script (sōsho) was finally perfected in 1598–9 and used in the printing of several important works, including a translation of the Guía de peccadores by Luis de Granada and the Rakuyōshū, a Chinese–Japanese dictionary.

The Jesuits and their converts were instrumental in effecting a number of innovations in printing in Japan, including the first recorded use of movable type to print in Japanese itself (as opposed to the romanized form of the language); the introduction of furigana (i.e. hiragana or katakana, syllabic characters printed in a smaller fount, to indicate the correct reading of the individual Chinese characters); the carving of two or more characters on a single piece of type; and the use of hiragana-script ligatures. By 1600, the Jesuits had handed over the day-to-day operations of the press—which had been moved from Kazusa to Amakusa to Nagasaki—to a prominent Japanese Christian layman, Thomé Sōin Gotō. Another layman, Antonio Harada, began printing Christian works in Miyako (Kyoto) in 1610 at the latest. It is uncertain whether he used traditional woodblocks or movable type in his printing office. When the missionaries were expelled from the country in 1614, the press was shipped to Macao, where it was unpacked in 1620 to print an abridged grammar of Japanese composed by João Rodrigues ‘Tçuzzu’ (‘the Interpreter’). Although some sources claim that the press was subsequently sold to the Augustinians in Manila, no conclusive evidence can be adduced to identify the press used in the Philippines with that of the Jesuits from the Japanese mission.

In the aftermath of Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s invasion of Korea, where movable type had been in use since the 13th century (see 43), the Japanese regent brought back Korean printing materials in 1592. As a result, the Emperor Goyōzei and Tokugawa Ieyasu published a number of books between 1593 and 1613 using both wooden and copper type (see 44). Whether either of these two independent developments in the history of Japanese movable-type printing exerted any influence on the other remains unclear.

After Japan closed her doors to the West in 1639, missionary printing ceased altogether. It would begin again in earnest only in the 1870s in Nagasaki and Yokohama, under the aegis of prominent members of the Foreign Paris Missions (MEP) in Japan, including Bernard Petitjean, Pierre Mounicou, and Louis Théodore Furet. Even before the proclamation of religious freedom by the Meiji government in 1873, the French missionaries had succeeded in printing catechisms in Japanese as early as 1865.

As Europeans began to travel to all corners of the earth beginning in the 15th century, they were determined not only to conquer new lands but also to spread their faith. From Johann Gutenberg they had learned the power of the printed word, and were determined to use this revolutionary new technology to Christianize Asia. The impact of these efforts varied depending on a number of circumstances. The two most significant variables were the ability to wield control as a colonial power (e.g. in the Philippines, but not in Japan or China) and the pre-existence of a widespread print culture (e.g. in China), or lack thereof (e.g. in India and Malaya).

This summary account of missionary printing in Asia also suggests that the principal difference between Roman Catholic and Protestant presses was the emphasis placed by the former on the exposition of Christian doctrine and the printing of catechetical treatises, and the early concentration by the latter on the preparation of partial or complete versions of the Bible in local languages. In either case, the missionaries made efforts to learn the local languages and pioneered the production of numerous dictionaries and grammars.

C. R. Boxer, A Tentative Check-List of Indo-Portuguese Imprints, 1556–1674 (1956)

C. J. Brokaw, ‘On the History of the Book in China’, in Printing and Book Culture in Late Imperial China, ed. C. J. Brokaw and K. Chow (2005)

T. F. Carter, The Invention of Printing in China and its Spread Westward, 2e (1955; repr. 1988)

A. Chan, Chinese Books and Documents in the Jesuit Archives in Rome (2002)

C. Clair, A Chronology of Printing (1969)

H. Cordier, L’Imprimerie sino-européenne en Chine (1901)

T. Doi, ‘Das Sprachstudium der Gesellschaft Jesu in Japan im 16. und 17. Jahrhundert’, Monumenta Nipponica, 2 (1939), 437–65

W. Farge, The Japanese Translations of the Jesuit Mission Press, 1590–1614 (2002)

R. P. Hsia, ‘The Catholic Mission and Translations in China, 1583–1700’, in Cultural Translation in Early Modern Europe, ed. P. Burke and R. P. Hsia (2007)

J. Laures, Kirishitan Bunko: A Manual of Books and Documents on the Early Christian Mission in Japan, 3e (1957; repr. 1985)

J. Toribio Medina, Biblioteca hispanoamericana (1493–1810) (7 vols, 1898–1907)

——Historia de la imprenta en los antiguos dominios españoles de América y Oceanía (2 vols, 1958)

J. Muller and E. Roth, Aussereuropäische Druckereien im 16. Jahrhundert (1969)

D. Pacheco, ‘Diogo de Mesquita, S. J. and the Jesuit Mission Press’, Monumenta Nipponica, 26 (1971), 431–43

J. Pan, ‘A Comparative Research of Early Movable Metal-Type Printing Technique in China, Korea, and Europe’, GJ 73 (1998), 36–41

—— A History of Movable Metal-Type Printing Technique in China (2001)

A. K. Priolkar, The Printing Press in India (1958)

W. E. Retana, Orígenes de la imprenta filipina (1911)

A. Kohar Rony, ‘Malay Manuscripts and Early Printed Books in the Library of Congress’, Indonesia, 52 (1991), 123–34

V. Rosenkilde, ‘Printing at Tranquebar’, Library, 5/4 (1949–50), 179–95

M. Saldanha, Doutrina Cristã em língua concani (1945)

E. Satow, The Jesuit Mission Press (1898)

D. Schilling, ‘Vorgeschichte des Typendrucks auf den Philippinen’, GJ 12 (1937), 202–16

—— ‘Christliche Druckereien in Japan (1590–1614)’, GJ 15 (1940), 356–95

G. Schurhammer and G. W. Cottrell, ‘The First Printing in Indic Characters’, HLB 6 (1952), 147–60

J. F. Schütte, ‘Drei Unterrichtsbücher für japanische Jesuitenprediger aus dem XVI. Jahrhundert’, Archivum Historicum Societatis Iesu, 8 (1939), 223–56

—— ‘Christliche japanische Literatur, Bilder, und Druckblätter in einem unbekannten vatikanischen Codex aus dem Jahre 1591’, Archivum Historicum Societatis Iesu, 9 (1940), 226–80

G. W. Shaw, ‘A “Lost” Work of Henrique Henriques: The Tamil Confessionary of 1580’, BLR 11 (1982–5), 26–34

—— The South Asia and Burma Retrospective Bibliography (1987)

N. Standaert, ed., Handbook of Christianity in China (2001)

R. Streit and J. Dindinger, Bibliotheca Missionum (30 vols, 1916–75)

M. A. J. Üçerler and S. Tsutsui, eds., Laures Rare Book Database and Virtual Library, www.133.12.23.145:8080/html/, consulted Apr. 2008

J. Wicki, ed., Documenta Indica (18 vols, 1944–88)

E. Wolf, 2nd, Doctrina Christiana: The First Book Printed in the Philippines. Manila 1593 (1947)