In 1904 Fairbanks boasted dozens of saloons and gambling dens— thirty-three of them in four blocks along First Avenue—all with no locks because they never closed. And city fathers were downright delighted when a Dawson prostitute, "Cheechaco Lil," established herself on Second Avenue, indicating her staunch faith in the future of the camp. Her arrival brought to four the number of "working girls" in Fairbanks—not nearly enough to meet local demand, but more girls were arriving daily.1

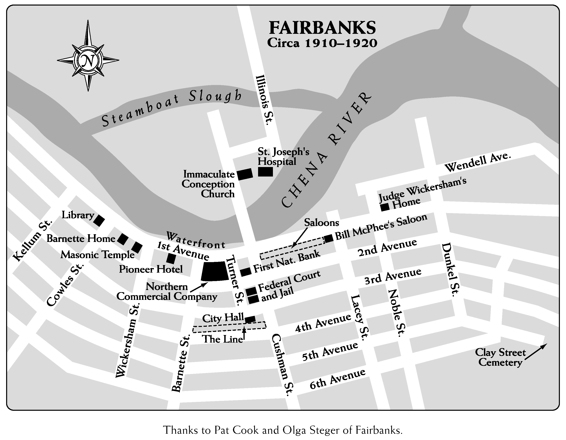

The founders of Fairbanks could not have picked a less likely place for a city. While other gold rush towns were accessible by ocean trade routes and the mighty Yukon River, this camp was in the Tanana Valley, deep in Alaska's Interior on the Chena (which had been given an Indian name that meant "Rock River" because of its shallowness in the dry season). The Chena was a remote tributary of the Tanana River, which was a major but remote tributary of the Yukon, in an unmapped area surrounded by mountains on three sides.2

Italian discoverer Felix Pedro, a.k.a. Felice Pedroni, a veteran prospector, was ill, disillusioned, and in debt when he staked his claim in the Tanana Valley. A year earlier, in 1901, Pedro had made his first major find here, but mapped it so poorly that he could not relocate it after a 130-mile trip to Circle to resupply.3 And he might have misplaced his second strike had not trader E. T. Barnette been dumped conveniently on a nearby riverbank with a year's supply of trading goods.

Barnette, a convicted felon who recreated himself as a respectable businessman, had chartered the stern-wheeler Lavelle Young after his own supply boat sank at the Yukon's mouth off St. Michael. He planned to establish a trading post about 400 miles up the Tanana River at Tanana Crossing, a telegraph site falsely rumored to be a future railhead.4 At Barnette's urging, his charter captain, Charles Adams, detoured to the Chena trying to get around Bates Rapids, commonly thought to block navigation on the Tanana, but the stern-wheeler went aground about seven miles above the mouth of the Chena. This was more than 200 miles downriver from Barnette's destination, but Captain Adams refused to continue.

It was late August 1901, and Barnette was beside himself until Felix Pedro and his partner, Tom Gilmore, came down from the hills to purchase their winter outfits, assuring him that a gold strike was imminent and more customers would follow.5 But it took a year for that to happen, and even after Felix had successfully staked Pedro Dome on July 28, 1902, the usual stampede did not ensue.

Anxious for business, Barnette ordered his cook, an outstanding athlete named Jujiro Wada, to run to Dawson in the dead of winter to announce the strike. Wada's arrival in Yukon Territory made headlines.6 However, the plan backfired when a Dawson contingent arrived that spring to find most of the Tanana Valley illegally staked (one man alone had tied up almost 3,000 acres) and no one making money yet. Dawson bartender James "Curly" Monroe, who'd brought $10,000 to invest, returned to the Klondike with his bankroll intact, predicting that perhaps in six months or two years the Tanana camp might become worthwhile.7 "Ham Grease" Jimmie O'Connor, another veteran, reported the diggings were so poor they would not support one dance hall.8

Indeed, the area's 500 or so miners appeared to be living on hope. Gold in the Tanana Valley lay more deeply underground than in previously mined locations.

It wasn't until late in 1903 that the undercapitalized Fairbanks miners—mostly old pros working with primitive hand tools— established that they had a major strike. By then, Felix Pedro had discovered a second, richer gold deposit on Cleary Creek, and "Two Step" Louis Schmidt, Dennis O'Shea, Jesse Noble, Tom Gilmore, James Dodson, and a few others also had struck it rich.9

Fairbanks's first dance hall opened April 20, 1903, and closed shortly thereafter.10 When Sarah Gibson came to town hoping to start a hotel in May, she wrote her son Tom in Dawson that there were lots of buildings going up and one dance hall but no girls yet. Her arrival brought the number of women in Fairbanks to six.11

By Christmas from 1,500 to 1,800 men were in the area, most of them seasoned miners. Judge James Wickersham, who talked E. T. Barnette into naming the town after soon-to-be U.S. Vice President Charles W. Fairbanks, included it in his 300,000-square-mile judicial district. After treeless, wind-strafed Nome, Judge Wickersham was quite taken by the valley's rolling forests and its farming potential. When Barnette presented him with a prime house lot and offered land for a courthouse as well, Wickersham made the town his headquarters, pronouncing it an "American Dawson."12

One year later, gold production increased from $40,000 to $600,000 and Fairbanks outdid its predecessor. "To walk down Front Street here one would think that one had been asleep and awakened in Dawson, so far as faces were concerned, for nine-tenths of the people here have been in Dawson," an old-timer reported.13

But Fairbanks was much wilder than Dawson, where the "yellow legs" (Northwest Mounted Police) were strict in law enforcement, observed George Preston, who worked at Northern Commercial. The American camp's reputation for violence was established when Alexander Coutts, an unpopular bear of a man, expressed a grievance over a building lot and was shot through the lungs by mining recorder William Duenkel.14 Coutts recovered, and Judge Wickersham allowed Duenkel to walk on $1,000 bond.

When angry Dawson miners threatened to lynch Jujiro Wada for luring them to Fairbanks for a "fake" stampede, the judge dispatched his brother Edgar to the site as a federal deputy marshal.15 Edgar Wickersham was subsequently fired as the result of a drinking problem, but maintaining order in that frontier town was a thankless task, even for the sober.16

Yet almost from its beginnings, Fairbanks provided surprising amenities: electricity, telegraph service, a telephone system, mail service, seasonal steamboat transport, and a government-pioneered trail to the deep water port of Valdez to the south. All these made women feel more comfortable in Fairbanks than in the rough-and-tumble settings of earlier camps. E. T. Barnette's wife, Isabelle, accompanied him on his first trip and stayed on. Judge Wickersham settled his family, and others followed suit. "Many of the earlier Fairbanks miners had been in the north for many years and were looking for a permanency and stability that the other communities of Dawson and Nome lacked," noted historian Gary Stephens. "There was a strong conservative element in the community."17

But because gold-mining in the Tanana Valley was labor-intensive, it also attracted a large number of virile young men. When gold production reached nearly $4 million in 1905, prostitutes and their pimps began flocking there.

The city of Fairbanks—well-organized from its inception and guided by Judge Wickersham's policy of moderately taxing vice for civic betterment—established a system of monthly fines that served as "license fees" for illicit operations, and welcomed the influx.

SEASONED PROSPECTORS

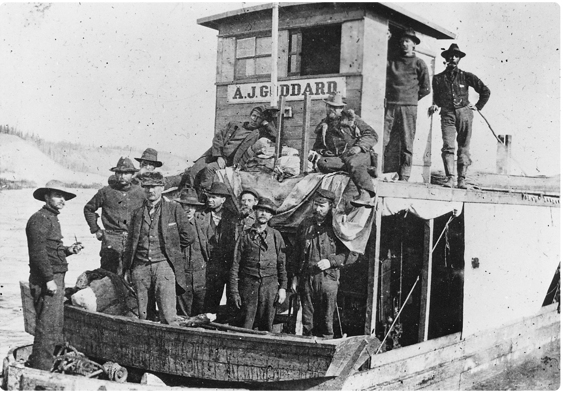

Fairbanks, in the heart of Interior Alaska, was settled by veteran prospectors who used riverboats as their main mode of transportation. Town founder E. T. Barnette arrived with his wife, but otherwise women were slow to move to the isolated region.

UAF, Ralph MacKay Collection, #70-58-238N.

"Are you a lady or a whore?" the city attorney would ask, meeting females off each incoming boat. "If you are a lady, pass on; if you are a whore, seventeen dollars and a half."18

The take averaged $1,200 a month, according to an informant for the Valdez News, and moralists in the rival settlement were scandalized.19

"Fairbanks papers are going into ecstasies over the fact that the town has been conducted for the last year without levying a property tax. Why the people should be proud of the condition of affairs there is incomprehensible," the Alaskan Prospector editorialized.

"The money, apart from licenses, used for running expenses of the town has been collected entirely from the sporting class by a system of fines. Every game in operation has to pay a monthly tax and the sporting element are assessed a heavy per capita tax. The town is supported by licenses collected from prostitutes and gamblers. This method of raising money is so obnoxious to the average person that one would think the people of Fairbanks would say as little as possible about it."20

FAIRBANKS FOUNDERS

Early Fairbanks residents worried that women might never settle in the gold rush community, and it took some time to attract them. This early town portrait includes Charles L. Thompson, owner of the prestigious Tanana Clud (eleventh from the left with tipped-back hat and a grey double-breasted suit), and Leroy Tozier, a lawyer who had made a find name for himself in Dawson (to Thompson’s right in the white hat).

Courtesy of A. Christopher, Blanche Cascaden, Pioneer Museum, Alaska.

Nome's crackdown on prostitutes and gamblers in 1904 and closure of dance halls and gambling dens in Dawson left Fairbanks as the only major gold camp where the demimonde could operate comfortably. "This means that the population of our town will be largely increased by that element, which is headed this way," noted the Fairbanks Daily Times in 1906, unfazed. "Our community has always had a fair proportion of its population who were identified with the class referred to but the community being small and these characters well-known a limited field for operation has been offered."21

In the same editorial, the Times editor boasted about the superiority of the Fairbanks Police Department, but its track record did not inspire confidence. Police Chief Tom Harker had just left town to avoid an investigation for "taking money from fallen women,"22 and James Hagen, appointed to replace him, had questionable associations with the underworld.

Suspicions were aroused when one T. E. Nordness committed suicide by cutting his wrists and then driving a bullet through his forehead after Police Chief Hagen had ignored for three days his complaints that he had been held at gunpoint and "cajoled" out of his entire life savings by a Floradora dance hall girl.23 Chief Hagen also failed to discover who had fired a five-gallon keg of gasoline "set for spite" at the Tanana Bottling Works, owned by two of the town's most flamboyant businessmen.24 Nor had he been much help when Gabrielle Mitchell, a.k.a. Louise Vassiaux (a prostitute well-connected with the Fairbanks underworld), beat Irene Wallace, a competitor, so badly that a doctor had to repair the victim's face. Gabrielle, who proudly demonstrated her prizefighting techniques to the court by "punching holes in the air to show how different blows could be delivered with force," was fined only fifty dollars. Irene, fearing for her life, fled on the next boat.25

Even tolerant Fairbanksans began to wonder about their law enforcement when Annie Fields, a.k.a. "Woodpile Annie," was reported to have shot herself in the head with Chief Hagen's .44. The suicide attempt allegedly took place at 8 a.m. on a Sunday at the cabin James Hagen shared with Tom Sites, a bookkeeper for the Tanana Bar. In fact Annie, "very much under the influence of drink or drugs," had tried to dispatch herself at the home of one of the town's most prominent citizens, and Chief Hagen apparently had been pressured into concocting a story for the press involving himself.26 The career lawman was fired about a month later on a vote of four to three by the Fairbanks City Council.27

Alaska's Episcopal Archdeacon Hudson Stuck, although hardened by the Texas cowboy towns where he had begun his career as a priest, was awed by Fairbanks violence.28 Later described by one biographer as a latent homosexual, Archdeacon Stuck had an inordinate fondness and sympathy for young men and was appalled at how frequently they were mugged, robbed, or brutally beaten by Fairbanks pimps and their women.29 But he was also a well-educated free thinker who realized that outlawing prostitution was no solution in a rough frontier setting. It was not lost on Stuck that the first grand ball of the Fairbanks Arctic Brotherhood, held shortly after his arrival in the fall of 1904, attracted only seventeen women to sixty-six men.30 Or that the fast-growing city depended on vice for the majority of its revenues.

The solution—quasi-legal prostitution in a carefully supervised restricted district—may have been suggested to Archdeacon Stuck by Luther Hess, who was the assistant U.S. district attorney under Judge Wickersham and who knew from personal experience how well it could work.

Born of a wealthy family in Milton, Illinois, Luther Hess had stampeded to Dawson via Dyea, then passed the Alaska Bar and moved to Fairbanks. When he returned to visit his hometown, flush from trading in mining claims and other northern business ventures, he urged friends to come North to make their fortunes. He found a protege in Georgia Lee, the beautiful, fun-loving daughter of a poor neighbor, and agreed to back her career as a prostitute in the Far North. To help her polish her trade before coming to Fairbanks, Luther arranged for Georgia to apprentice in the red light district of St. Louis.31

The first city in America to regulate vice, from 1870 to 1874 St. Louis had openly operated a red light district with over 700 prostitutes, under the "Social Evil Ordinance." It provided police protection for both management and clients, medical inspections, and even free hospitalization for prostitutes with venereal disease. Had the St. Louis system not become a political football, it might have become a national model, and the city remained progressive in dealing with its demimonde.32 The plan Archdeacon Stuck urged Fairbanks city fathers to adopt in 1906—the same year Georgia Lee arrived fresh from training in St. Louis—was almost identical to St. Louis's Social Evil Ordinance.

The archdeacon's timing could not have been better. Fairbanks's annual gold revenues had exceeded $9 million that year, and the town was just starting to rebuild after devastating bouts with fire and flood. Block 48, a long stretch slated for rebuilding on the even-numbered side of Fourth Avenue between Cushman and Barnette Streets, just beyond the heart of town, was selected for the district. With the backing of the town council, Stuck convinced Andrew Nerland to help with land title transfers and other business arrangements.33

Though a staunch Presbyterian and a family man, Andrew Nerland was the perfect choice for the project. A Norwegian-born paint and wallpaper supplier, he had moved from Dawson to become one of Fairbanks's leading businessmen. Much of the town's demimonde traded at his shop. Earlier Nerland had chaired the committee that moved the red light district out of Dawson's city limits, so he understood the economics of prostitution better than most.34 And his wife, Annie, had just moved south for the sake of their small son's health,35 which would spare her the embarrassment of her husband's delicate assignment.

In Dawson, prostitutes had been forced to rent from unscrupulous landowners whose real names were cleverly concealed. To Andrew Nerland's credit, the Fairbanks women were given the opportunity to purchase lots in their district, and rents were kept fairly reasonable by city fathers who invested openly.

While Nerland arranged the land transactions, Archdeacon Stuck briefed the police chief and wrote the regulations. Prostitutes could no longer solicit in bars or dance halls, but must confine all business activities to their special district, which would be carefully patrolled. They were to limit movie-going to special, after-hours shows especially for them, and were not to mix and mingle in respectable society. They also must agree to regular health inspections and continue to pay the monthly fines on which the city subsisted. In return, they would be allowed to operate without fear of legal reprisals, with the backing of that well-heeled community. Many prostitutes, long the target of unscrupulous lawmen and politicians, saw it as the chance of a lifetime.

Opposed to the plan were a number of moralists, who found themselves strangely allied with rent-gouging landlords and saloon-keepers who had depended on wild women to lure male customers. "Archdeacon Stuck was burned in effigy as the man who was responsible for establishing a regular district for prostitutes," recalled Albert N. Jones, an Episcopal priest later assigned to Stuck's Fairbanks post. "The dance hall girls, some saloon-keepers, etc. found this decision bad for business and so the Archdeacon was symbolically 'worked over.'"36

Although no official ordinances were passed, the city backed Stuck's plan. On September 8, 1906, the Fairbanks Evening News reported an emphatic grand jury protest against "licensed women" (Fairbanks prostitutes who paid their fines) being permitted to live wherever they choose. The council took heed, for just five days later the Fairbanks Daily News Miner referred for the first time to a "woman of the restricted district."

The paper was reporting the case of Willey Hooper, "a colored girl on Fourth Avenue" who was robbed by Ike Moses, a tailor. Ike had beaten Willey in an attempt to steal her diamond earrings, valued at $500. Police officer Jack Hayes arrested the man within a half-hour, and Willey assured the judge that her attacker—broke and desperate to raise money for his family Outside—was crazy.37

Once the restricted district (also referred to as "The Line" and "The Row") was well established, complaints of muggings and robberies ceased. In fact, miners began leaving their gold dust and paychecks with girls in the district for safekeeping if the banks were closed when they got to town.38 "Respectable women" were spared having to deal with annoying propositions from sex-starved miners who could not always tell wanton women from those of stout moral fiber.

Initially the Line had about fifty inmates living in small log houses built side by side, some no bigger than six by nine feet. The "cribs," as they were called, were smartly painted, boasting bright awnings and leaded glass windows. Each had a tiny kitchen with an entrance on Fourth Avenue that was seldom used.39 Business was solicited from a living room at the back of each house, accessible via boardwalk through an alley. Every living room had a picture window through which men "shopping" for love could see the occupants.

"These women were not the noisy type of hooker pictured in the dance halls," recalled Robert Redding, who delivered water to the Line before it was plumbed. "They were quiet, neatly dressed, and quite often were reading the current bestseller. They didn't need to be noisy. They knew why they were there and so did the customers."

A potential client entered through the back door and might visit in the living room a while before heading for the snug little bedroom sandwiched between it and the kitchen.40 Not all visitors had romance in mind, either. One of the girls owned the best library in the Far North and attracted an odd following of miners who just came for a good read. And the Line also became a popular after-hours drinking spot.41

Although town founder E. T. Barnette did not speculate in red light real estate, most of the city council did, including bar owners Charles Thompson and Dave Petree, and teamster Dan Callahan. Barnette did try to force the girls to vote his party line, but that attracted such embarrassing press coverage he apparently gave up on the idea.42

Of even greater concern was a rash of suicides by Fairbanks prostitutes which began during the holiday season in 1906. Following a long period when she appeared to be in good spirits, well-liked Kate Ambler, who was working to support her child in Tacoma, baffled friends by downing strychnine and refusing the aid of a doctor.43

THE FAIRBANKS LINE IN OPERATION

This is the only known photo of would-be patrons “window-shopping” in the red light district. If a prostitute’s window was uncurtained, it usually meant she was open for business and could be viewed by prospective customers before they negotiated. While many of the girls posed willingly for photographers, patrons were usually less willing, which may explain the shaky quality of this photo.

Michael Carey Collection.

Nine days later "French Alice," whose true name was unknown even to close friends, swallowed patent antiseptic tablets, her second suicide attempt in six weeks. "Unrequited love, on the part of one of the men who prey upon the earnings of fallen women for their livelihood, is said to be the cause of the woman's attempt to commit suicide," the Fairbanks Evening News speculated.

Then Frankie Polson succeeded with strychnine. Annie Fields followed with her bizarre shooting attempt, supposedly out of dislike for the police chief but more likely prompted by the departure of her pimp.44 Katzu Okabazashi cured her longing for a heartless Japanese bartender by taking mercury-bichloride.45

However, it took the tragic death of Marie LaFontaine, a well-respected prostitute who worked under the name of LaFlame, to move Fairbanks officials to action. One of the most orderly women in the district, Marie never had been known to drink, but the day before her death she went on a terrible bender, causing a disturbance at the dance hall and breaking a windowpane with her fist. Concerned friends got her into police custody, but after being released she continued to drink and finished off the evening by downing a two-ounce bottle of carbolic acid, which she did not survive.46 Apparently her pimp, Emille Leroux, who earlier had been run out of Nome on charges of white slavery, had gambled away the savings she had planned to use to visit her aging mother and sister in Montreal.47 Perhaps Marie had hoped to start over.

Outraged, some of the town's most respected citizens served as Marie's pall bearers. Their floral tribute was extraordinary. The ladies of St. Matthew's choir sang at her service. And within twenty-four hours, the Fairbanks City Council passed a harsh ordinance that made it impossible for pimps to function.48

According to the ordinance, a prostitute could answer to a lover or business manager, but that was her choice. Pimps (also called "macques") were forbidden to reside on the Line, and since prostitution was quasi-legal, pimps could not control women by threatening to turn them in to the authorities. If a girl was mistreated by a pimp, she could easily get rid of him by having him arrested. Plenty of customers found their own way to the restricted district without pimps luring them there; local bartenders would refer more customers for a reasonable commission, a service performed by taxi drivers in later years. So for the first time, perhaps in the history of the United States, it was possible for a common prostitute to survive on her own, with a real chance of building a better life.

While the city council was liberal, attuned to its frontier public, federal officials were horrified by quasi-legal prostitution, as was the Fairbanks grand jury. In April of 1908, on the jury's recommendation, District Judge Silas H. Reid ordered immediate closure of the dance halls in the Third Judicial District, and they never reopened. Judge Reid ignored the jury's recommendation to cancel liquor permits of any business permitting women on its premises, but he did order licenses taken from those who allowed women of ill repute to live or loiter upon the premises or allowed them to solicit drinks for a percentage.49 When the Tammany Dance Hall tried to circumvent the order by staying open but selling only soft drinks, Judge Reid ordered it closed anyway.50

Following Judge Reid's lead and his own righteous bent, newly appointed District Attorney James Crossley, a former state senator for Iowa, saw reform as a quick way to make a name for himself. On the job less than a month, he engineered raids on a dozen or so of the town's most prominent citizens who bedded women of the demimonde. D. A. Crossley had them arrested on charges ranging from adultery and unlawful cohabitation to conducting a bawdy house.

Among those jailed was Charles L. Thompson, owner of Fairbanks's most prestigious bar, the Tanana Club. Although connected with the underworld, Charles Thompson was well loved as the town's fairest baseball umpire and the only citizen with both the money to finance public fireworks displays and the courage to set them off. The bar owner was astonished to be charged with adultery for sleeping with his mistress, prostitute Georgia Lee, because neither of them was married and everyone in town knew it. At the urging of his astute attorney, Thompson pleaded guilty and paid the fifty-dollar fine anyway, making the whole proceeding a bit of a farce.

Worse yet, Crossley laid the same charge on Thomas Marquam, the town's cleverest defense lawyer, who proceeded to defeat the district attorney in court. Others simply shrugged and paid their fines because unlawful cohabitation wasn't a big deal on the frontier.51 Somewhat deflated, D. A. Crossley lay low for a while. As their concession to moral decency, the city fathers enclosed the Line with a twelve-foot-high board fence.52

Nationally, Americans had become concerned about "white slave" traffic, and in 1908 the U.S. signed an international treaty aimed at stopping the enslavement of girls and women of any color for prostitution. The media, led by the august New York Times and early movie-makers, convinced citizens that international rings of white slavers were kidnapping as many as 60,000 women a year. Hysteria ensued, but crime sweeps across the nation uncovered no evidence to prove the problem existed. The New York Times and other reputable media quickly dropped the subject, which within five years would be referred to as the "myth of an international and interstate 'syndicate' trafficking in women" and a "figment of imaginative fly-gobblers." But while white slavery briefly remained a cause celebre, a number of public officials used it to build their careers and fight prostitution in general.53

Among the most zealous was Kazis Krauczunas, an immigration inspector for the U.S. Department of Commerce and Labor based in Ketchikan, Alaska, who decided after a preliminary investigation that Fairbanks was a hotbed for the trade. In June of 1909, Krauczunas's excited superiors dispatched him to Fairbanks to arrest white slavers and deport the women they had corrupted. He was forearmed with a list of names provided by Captain T. A. Wroughton of the Northwest Mounted Police, which earlier had driven many of the suspects out of Dawson.54

Two of the worst offenders, Inspector Krauczunas decided, were Felix Duplan,55 who had skipped bail in Canada, and his wife, Lily DeVarley, who had been convicted of running a disorderly house in South Dawson and asked to leave town. Lily, beautiful and well-liked, had worked quietly on the Fairbanks Line with two sisters since its inception.56 Neither she nor Felix had recruited inexperienced, unconsenting young women, nor did they have Fairbanks police records. However, Krauczunas knew that on June 17 of that year they would complete three years of U.S. residency, making it all but impossible to deport them. Realizing he would not come north before then, Krauczunas wired Fairbanks's U.S. marshal, requesting that he arrest the couple. On his arrival five days later, Krauczunas was relieved to find that his request had been honored.