Sasha Engelmann and Derek McCormack

Atmosphere has become one of the most alluring of concepts across the social sciences and humanities. Its appeal is manifold, but it is particularly important because it allows us to grasp the affective materiality of spacetimes that are diffuse and excessive of bodies yet also palpable through the sensory capacities of those bodies (Anderson 2009). The emergence of atmosphere as an alluring concept within the social sciences and humanities also raises important methodological and empirical issues (Anderson and Ash 2015). Not least of these are the issues that revolve around the promise and limits of sensing.

A first issue concerns what is being sensed when we invoke either atmosphere or the atmospheric. When we speak of the force of atmosphere as something that registers in bodies of different kinds, are we referring to the quality of an entity, or to variations in a process that is never reducible to the category of entity? Is atmosphere an entity, the quality of an entity, or something excessive of entities? This issue is important not least because it has implications for any claim about the possibility of atmospheres as not only distributed but also shared.

A second issue concerns the problem of how to sense atmosphere. On one level, the appeal of atmosphere is that it suggests immersion in a spacetime that, while vague, is somehow directly and immediately sensed in and for human bodies. But we cannot take for granted this capacity to sense atmospheres: no less than other registers of sensing, such as seeing, it depends upon the complex relationship between experience, technique and technology.

In turn, this leads to a third issue: if we cannot take the capacity to sense atmosphere as a given, then how can we cultivate it as part of interdisciplinary methodological experiments? Here experiments with performance practices offer important possibilities. In many ways performance practices offer researchers in the social sciences and humanities a repertoire of techniques for generating atmospheres and for sensing variations in their intensity and distribution (see Böhme 1993; Thrift 2008; McCormack 2013). Performance practices foreground how atmospheres emerge in the relation between forms of skilful embodiment, techniques of stagecraft, and objects of different kinds. In some ways, of course, these practices amplify and intensify other styles of sensing atmospheres that have long been honed through ethnographic modes of attunement to the structures of feeling of the ordinary. These styles of sensing are not necessarily staged, even if they involve attending to scenes of life in which atmospheres become palpable with particular force (Stewart 2011).

A fourth issue concerns the problem of how to produce accounts of atmospheres that in some way evoke a sense of the atmospheric. The craft of writing remains an important domain of expertise through which to do this (Stewart 2011). At the same time, researchers in the social sciences and humanities have collaborated with a range of performance-based and creative researchers to generate atmospheric spacetimes (Engelmann 2015a; Hawkins 2016).

A fifth, and final issue concerns the political or ethical ends to which any interdisciplinary experiment with sensing the atmospheric might be put. The condition of being immersed within atmospheres is not necessarily benign (Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos 2015). Given this, we might ask if the goal of any collaboration is to critically demystify the atmospheric qualities of spacetimes, to create new kinds of immersive atmospheric spacetimes, or to engage in some affirmative combination of both. In a world where atmospheres are becoming the ‘object-target’ (Anderson 2014) for various forms of intervention, should we be aiming to produce new forms of atmospheric politics, or be content to critique the operationalization of atmosphere across different domains of life?

These questions would be challenging enough if we could restrict atmospheres to the affective orbit of human sensory capacities. The atmospheric is not a domain circumscribed by phenomenological modes of conscious sensing, however. Indeed, much of the data and processes that can now be sensed operate below and before thresholds of human awareness. The domain of what Mark Hansen calls atmospheric media is becoming ever more infrastructurally ambient, and is fading into a background that nevertheless continues to shape what shows up as a foreground (Hansen 2012). But it is not only the expanding domain of technical sensing that should cause us to question the primacy of the human in relation to the question of sensing atmospheres. It is also the fact that atmosphere does not refer only to a field of affective experience. It refers also to an envelope of gases that surrounds the Earth, and other planets for that matter.

To speak of atmosphere is to invoke a gaseous medium in which different forms of life are immersed and to which they are exposed in a relation of respiration. Variations in gaseous atmospheres are meteorological: they show up as gradients in temperature, pressure, humidity, etc. These variations are part of the affective turbulence of the world. Sometimes these variations can be, and are, sensed in human bodies, or in the experiential texture of what Tim Ingold calls ‘weather worlds’ (2015). These variations do not need to be sensed in human bodies to make a difference, or to be considered affective, however: they can be sensed in non-human bodies and devices of various kinds through the capacities of those bodies to be affected or perturbed (Bryant 2014; Ash 2013).

The question of how to sense atmosphere involves exploring possibilities for sensing the elemental materiality of spacetimes that are both affective and meteorological, and variations in which can be sensed across particular arrangements of bodies and devices. Methodologically this never just involves a kind of static immersion within a milieu that reveals itself fully to a body. It involves, instead, the problem of how to sense variations in an expanded elemental milieu, while also finding ways of moving with these variations to enhance our capacities to act. This can be understood as the elaboration of an expanded sensory ethology, in which the properties and qualities of elemental atmospheres are sensed through different assemblages of bodies and devices.

Elements of this kind of approach characterize ongoing experiments with practices and politics of sensing across a range of empirical, conceptual and political domains. Here we could point to the work, for instance, of Jennifer Gabrys (2016), who highlights how the scope of sensing is expanding in all kinds of ways that complicate the primacy of human agency or experience. Equally, we could point to the kinds of practices of participatory sensing undertaken by organizations such as Public Lab (see https://publiclab.org). Central to this work is the employment of a range of relatively simple devices (including cameras, technical instruments and kites) with which a range of processes, including different kinds of air pollution, can be sensed. These are processes that might not be ordinarily available for monitoring and scrutiny. Equally, as far as possible, the devices are not black-boxed: they remain open for hacking and modification by a growing community of users.

Some of these devices used by groups like Public Lab are particularly useful for sensing atmosphere. Simple things such as kites, sails and balloons have all long been used for feeling and moving with the variations in elemental atmospheres (Ingold 2009; Serres 2012; Flusser 1999). These devices might appear anachronistic in a world in which capacities to sense have become ever more diffuse, algorithmic and pre-phenomenological. Nevertheless, both alone and in combination, they have the capacity to generate opportunities for sensing atmospheres in important ways.

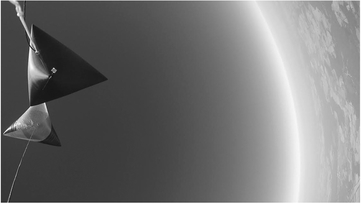

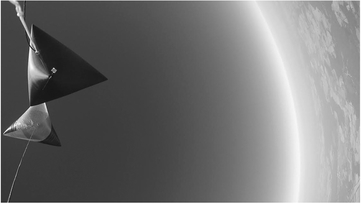

Consider one of these devices: the balloon. As a device for atmospheric sensing, the balloon interests us in a variety of ways. It has long been implicated in the emergence of new forms of sensing, both as a platform for human journeys into the atmosphere, and as a vehicle for various forms of remote sensing and atmospheric sounding. At the same time, the balloon has been used to generate aesthetic works responsive to the elemental conditions in which they are immersed. The multiple possibilities of the balloon in this regard make it a particularly interesting object for exploring interdisciplinary experiments in sensing atmospheres. In making this claim we draw upon involvement in ongoing collaborative work with Berlin-based artist and architect Tomás Saraceno (see Saraceno, Engelmann and Szerszynski 2015; Engelmann, McCormack and Szerszynski 2015).1 Saraceno’s work is multiple and manifold, but central to this work are experiments with different ways of being and becoming airborne, organized around the speculative promise of collective forms of life in the air. There are many devices through which Saraceno experiments with this promise. One of these is the solar balloon, which, unlike other balloons, uses no helium, hydrogen, solar panels or burners of any kind: it relies instead only upon energy from the Sun during the day, and infrared radiation during the night (Figure 3.8.1).

The range of Saraceno’s experiments lies far beyond the scope of this short piece, but there are a number of important points worth making about them insofar as they reveal what it involves to develop an interdisciplinary approach to sensing atmospheres. The first is the way in which these experiments foreground how the elementality of atmosphere is sensed in ways that do not obey any strict division between the natural or the social, or the affective and meteorological. Instead, in the shape of what Saraceno calls a solar sculpture, the balloon envelope becomes a device that senses variations both in the meteorological conditions in which it is immersed and in the elemental force of the Sun.

Then, and second, these works reveal how such sensing is a collective assemblage of both human and non-human participants, energies and forces (Serres 2008). Clearly, once aloft, a solar sculpture can remain in the air both day and night by absorbing short-wave energy from the Sun during the day and infrared radiation from the Earth during the night. However, the process of its taking to the air involves the enactment of a form of distributed expertise in which knowledge of the prevailing meteorological conditions, including wind-speed, cloud-cover, etc. is crucial. In turn, and third, such experiments reveal how sensing atmospheres is both technical and aesthetic. Sensing atmospheres is not about experiencing elemental natures in the raw: rather, it is about how our capacities to sense can be enhanced through as simple a technical operation as the folding and stitching of a fabric envelope. Equally, this sensing is not only something that takes place in the air: the process of fabricating and inflating the envelope on the ground generates atmospheres of involvement and participation.

Our own experience of participating in experiments with these devices reminds us of how interdisciplinary methods have the potential to be political insofar as they generate novel distributions of sensing atmospheres. On one level, this is evident through the kinds of atmospheres that gather around the prospect of a launch, atmospheres with the potential to generate new orientations in bodies towards the elemental conditions in which those bodies are immersed. It is also evident in the way in which, even when inflated on the ground, these envelopes provide spaces in which to gather. We can see this in one of the projects in which Saraceno is involved, Museo Aero Solar (Figure 3.8.2). This participatory project assembles around a solar balloon fashioned and fabricated from reused plastic bags. Individuals who donate plastic bags can participate in the solar balloon’s fabrication and its eventual launch; both of these processes draw bodies in affectively through the shaping and sensing of something becoming airborne.

Figure 3.8.1 Tomás Saraceno Aerocene, launches at White Sands (NM, United States), 2015. The launches at White Sands and the symposium ‘Space without Rockets’, initiated by Tomás Saraceno, were organized together with the curators Rob La Frenais and Kerry Doyle for the exhibition ‘Territory of the Imagination’ at the Rubin Center for the Visual Arts. The sculpture D-OAEC is made possible due to the generous support of Christian Just Linde. The artistic experiment achieved two world records of the first and the longest solely solar flight by a lighter-than-air vehicle. (Courtesy the artist; Pinksummer contemporary art, Genoa; Tanya Bonakdar, New York; Andersen’s Contemporary, Copenhagen; Esther Schipper, Berlin. © Photography by Studio Tomás Saraceno, 2015.)

But the distribution of atmospheric sensing is also evident in other, less immediate ways. This is perhaps more evident in Saraceno’s recent open-source artistic project, Aerocene (Figure 3.8.3). The larger aim of the Aerocene project is to generate the conditions through which new forms of life in the air might become possible. On the way to this, Saraceno has undertaken various tethered flights with solar sculptures, and some free flights without passengers. These latter flights rely upon technologies for tracking the movement of the solar sculpture. These technologies and their diagrammatic renderings of movement can also provide lures, in the shape of alluring abstractions that allow individuals and groups to track and trace the movement of solar sculptures.

Figure 3.8.2 Museo Aero Solar in Prato, Italy. Museo Aero Solar is a collaborative art project initiated by Tomás Saraceno, Alberto Pessavento and many other friends and collaborators around the world. (Photo: Janis Elko Museo Aero Solar, 2009 www.museoaerosolar.wordpress.com.)

Figure 3.8.3 Tomás Saraceno. Aerocene Gemini, Free Flight, 2016. (Courtesy the artist; Pinksummer contemporary art, Genoa; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York; Andersen’s Contemporary, Copenhagen; Esther Schipper, Berlin. © Photography by Tomás Saraceno, 2016.)

Experiments with solar balloons or solar sculptures are not the only interdisciplinary method for sensing atmospheres. But they remind us how the affective-meteorological materiality of atmospheres can be sensed and generated as part of the methodological repertoire of the social sciences. This sensing can be understood as a form of sounding (see Dyson 2014; Engelmann 2015b), where sounding is both the assaying of a milieu and its collective enunciation. Developing this, and drawing upon the kinds of experiments undertaken by Saraceno, it might be possible to imagine and devise new methods for sensing atmospheres in which the meteorological atmosphere itself becomes part of the infrastructure of sensing. These experiments would necessarily employ different devices and practices for learning to be affected by the force of the atmospheric as an elemental variation in both meteorological and affective spacetimes. To be sure, these experiments would afford opportunities for generating envelopes of experience that we might understand as particular kinds of atmospheres of immersion. But they would also stretch the envelope of atmospheric sensing far beyond the limits of the human body. In doing so, these experiments would provide opportunities for what, following Felix Guattari, we might call the ‘re-singularizing’ (1995) of capacities to sense the elemental conditions in which diverse forms of life take shape. They would generate situations of co-fabricated assembly in which atmospheric conditions are made explicit for sensing by bodies whose very forms of life are dependent upon those conditions.

References

Anderson, B. (2009). Affective atmospheres. Emotion, Space and Society, 2(2): 77–81.

Anderson, B. (2014). Encountering Affect: Capacities, Apparatuses, Conditions. Farnham, UK: Ashgate.

Anderson, B. and Ash, J. (2015). Atmospheric methods. In P. Vannini (Ed.) Nonrepresentational Methods: Re-envisioning Research (pp. 34–51). London: Routledge.

Ash, J. (2013). Rethinking affective atmospheres: technology, perturbation and space-times of the nonhuman. Geoforum, 49(1): 20–28.

Böhme, G. (1993). Atmosphere as the fundamental concept of a new aesthetics. Thesis Eleven, 36: 113–126.

Bryant, L. (2014). Onto-cartography: An Ontology of Machines and Media. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Dyson, F. (2014). The Tone of Our Times: Sound, Sense, Economy, and Ecology. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Engelmann, S. (2015a). Toward a poetics of air: sequencing and surfacing breath. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 40(3): 430–444.

Engelmann, S. (2015b). More-than-human affinitive listening. Dialogues in Human Geography, 5(1): 76–79.

Engelmann, S., McCormack, D. and Szerszynski, B. (2015). Becoming aerosolar and the politics of elemental association. In T. Saraceno, Becoming Aerosolar, Exhibition Catalogue, 67–101. Vienna: 21er Haus.

Flusser, V. (1999). Shape of Things: A Philosophy of Design (Trans. A. Mathews). London: Reaktion Books.

Gabrys, J. (2016). Program Earth: Environmental Sensing Technology and the Making of a Computational Planet. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Guattari, F. (1995). Chaosmosis: An Ethico-aesthetic Paradigm (Trans. P. Bains and J. Perfanis). Sydney: Power Publications.

Hansen, M. (2012). Ubiquitous sensation or the autonomy of the peripheral: towards an atmospheric, impersonal and microtemporal media. In U. Ekman (Ed.) Throughout: Art and Culture Emerging with Ubiquitous Computing (pp. 63–88). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hawkins, H. (2016). Creativity. London: Routledge.

Ingold, T. (2009). The textility of making. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 34(1): 91–102.

Ingold, T. (2015). The Life of Lines. London: Routledge.

McCormack, D. (2013). Refrains for Moving Bodies: Experience and Experiment in Affective Spaces. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos, A. (2015). Spatial Justice: Body, Lawscape, Atmosphere. London: Routledge.

Saraceno, T., Engelmann, S. and Szerszynski, B. (2015). Becoming aerosolar: from solar sculptures to cloud cities. In H. Davis and E. Turpin (Eds.) Art in the Anthropocene: Encounters among Aesthetics, Politics, Environments and Epistemologies (pp. 57–62). London: Open Humanities Press.

Serres, M. (2008). The Five Senses: A Philosophy of Mingled Bodies (Trans. M. Sankey and P. Cowley). London: Athlone.

Serres, M. (2012). Biogea (Trans. R. Burks). Minneapolis: Univocal.

Stewart, K. (2011). Atmospheric Attunements. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 29(3): 445–453.

Thrift, N. (2008). Non-representational Theory: Space, Politics, Affect. London: Routledge.