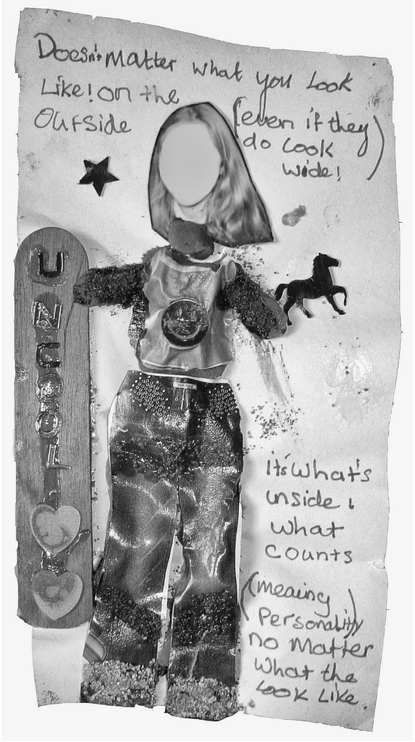

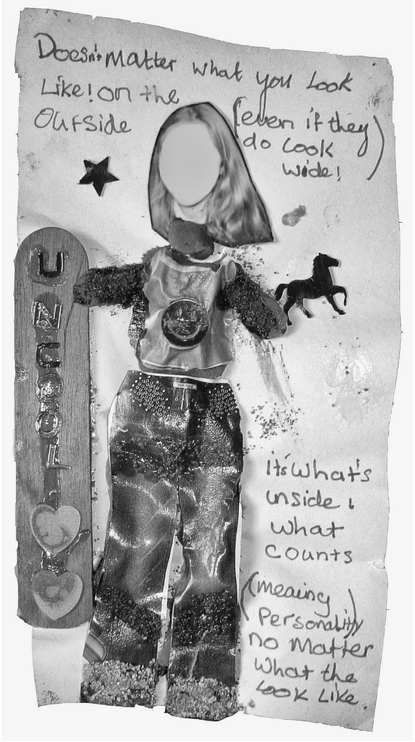

Figure 1.6.1 Anna’s image

Rebecca Coleman

A focus on imaging enables a consideration of the ways in which images might be the subject or outcome of a research project, and also an integral part of doing it. In this contribution, I consider some specific images that have been made in my research, both by research participants and myself. However, the main focus of the chapter is on understanding imaging as a research methodology that involves processes of making, assembling and circulating. In this sense, I am interested here not so much in how images may be considered as data, but more in how they may participate in the creation and dissemination of research; in what images might do in and for the research process. In particular, I place emphasis on the ‘ing’, in order to indicate the processual character of making, assembling and circulating – these are dynamic and transformational practices – and of images – which are themselves understood as potentially unfinished, sensory and affective experiences (rather than static objects or texts).

Such an understanding of the role of images in research might appear rather obvious to those in the performing and visual arts involved in practice research, where arts and media practices are recognized as generators of knowledge, and perhaps as performative interventions. However, with some notable exceptions, in the social sciences images have largely been considered as representations to be analysed in order to make sense of patterns and inequalities in visual culture, and/or as means of documenting encounters and experiences with the social world. While these approaches remain important, this contribution aims to explore some of the ways that the social sciences might take up practices developed in, and/or inspired by, art and design, and as a consequence might work with imaging as a research practice. Hence, I make interdisciplinary methodologies and methods the focus of my discussion, paying particular attention to the conceptual and practical issues that such approaches provoke.

I discuss two examples of how my research has worked through different imaging practices: the first involves research participants making collages, and the second involves me, as researcher, making and sending postcards. The images at stake here are thus broadly understood. They include collages and postcards both as images themselves, and as images that are made through a range of materials including other images, as I discuss below. My understanding of imaging is similarly broad. I consider how imaging can potentially involve multiple and diverse aims and practices, how different participants within a research project might (or might not) produce and circulate images, and how imaging as interdisciplinary methodology raises a number of questions that require further attention. While this chapter explores two examples from my own research, it is important to note that this focus is not prescriptive; other still and moving images and imaging practices (e.g. those involving videos, painting and drawing) might also be relevant to the suggestions I make here. That is, my understanding of images as open-ended experiences and of imaging as processual and transformational might lend itself to a range of approaches that are concerned with the non-representational, sensory, and inventiveness of the social world.

The understanding of imaging that I outline above can be unpacked through a first example of a project with young women on how they experience their bodies through images (Coleman 2009). In this research, I wanted to empirically study how these girls’ experiences of their bodies emerged and were arranged through relations with different kinds of images. Much feminist research on girls’ bodies and images concentrates on media images. While these images were raised as significant, what also became apparent in my research was that other images – including photographs, mirror images, and comments about their bodies from other people – were also important. Methodologically, I included image-making sessions alongside the more traditional sociological methods of individual and group interviews.

The aim of these sessions was to try to integrate images into the research, so that images were not just the subject of the research (what it was about), but part of how images were themselves studied (a methodology). I was also interested in encouraging participants to visualize and examine their experiences of their bodies.

The sessions involved the girls collaging images of their bodies through materials from different sources, including magazines, a Polaroid camera, craft materials, make-up and sweet wrappers (see Figure 1.6.1, and also Coleman 2009). To begin to think through these collages, the notion of assembling is particularly helpful. An assemblage refers to a temporary and changing arrangement of multiple parts (Deleuze and Guattari 1987). The collages made by the girls can thus be understood as assemblages; they are constituted by materials taken from various sources, which are arranged in ways that demonstrate how they have been transformed in the move from one source and setting to another (e.g. from a magazine to a collage, from mass media to a classroom to various academic publications), and in the relations the parts have with each other (e.g. through how they may be juxtaposed, and/or organized so as to create a particular impression).

Furthermore, in these collages, issues concerning change are highlighted. For example, Anna’s collage (Figure 1.6.1) highlights how understandings of a person might change depending on whether they are based on looks and appearance or ‘what’s inside’. Other participants juxtaposed photographs of themselves with images from mainstream women’s magazines. Fay, for example, assembled a photograph of herself with magazine images and wrote ‘I wish’, indicating what she experiences her body to be, and what she would like it to become. Here, then, imaging as research methodology is a process through which specific images are created, which can then be analysed as social science data.

However, as well as the images themselves being critically analysed, the research methodology of imaging is itself worth considering. The sessions were productive in that the girls clearly enjoyed participating, with some asking for the sessions to be extended so they could continue working on their collages. While making their images, some of the participants also began working together in informal ways. For example, discussing what materials and techniques others had used for inspiration for their own collages, and having seen how others had included them,

Figure 1.6.1 Anna’s image

a number of the girls incorporated pipe cleaners into their images towards the end of the session. As well as belonging to an individual participant, the images produced were therefore clearly shaped by the group experience, enabling me to reflect upon how different methods produce different kinds of knowledges and data (a topic that commonly features in discussions about the strengths and weaknesses of individual as opposed to group interviews, for instance).

The imaging methodology also raised a number of challenges. After they had made their collages, I asked the girls to explain them to the group. This was not so much because I think it is necessary for visual, sensory or imaging research methodologies to be translated into words, but rather to encourage the girls to reflect on their images, and the experiences of their bodies with which they had engaged (see also the chapter on Drawing for a similar point) and to share them with the group. However, the girls found it difficult to verbalize their experience of making the images and the images they made. Imaging as methodology, therefore, raises questions regarding whether and how articulations about and assessments of such practices are necessary, possible and/or desirable. Relatedly, although I had wanted to make images a central part of the research, as a sociologist more familiar with writing about textual data, I struggled to know what to do with the images once they had been made. Indeed, in the book on the research, I discuss the images in one section of one chapter, and treat them similarly to extracts from the interviews I conducted. This technique demonstrates how visual and sensory as well as textual data are valid, and how imaging is a productive methodology; however, incorporating the images into a relatively traditional written publication was perhaps not the most appropriate means of attending to either the specificity of the images that were produced, or the imaging methodology deployed.

A second example is a project that attempts to put speculative visual methods to work to explore a recent patent by Amazon for ‘speculative shipping’, where goods will be shipped in advance of order to geographically distributed hubs to minimize the time between online order and delivery (see Coleman 2016). To solve the problem of returning speculatively shipped products to the warehouse if the item is not subsequently ordered, the patent proposes to deliver the package ‘to a potentially interested customer as a gift’ to ‘build goodwill’ (Spiegel et al. 2013). This notion of creating goodwill through the delivery of unexpected packages in the post is noteworthy, given how the patent for speculative shipping was described in the press as ‘delightful and exciting [. . .] We like getting things in the mail, even if we didn’t ask for them’ (Kopalle 2014).

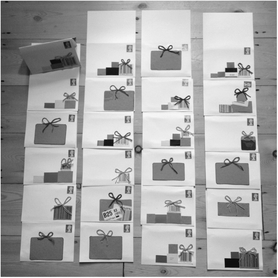

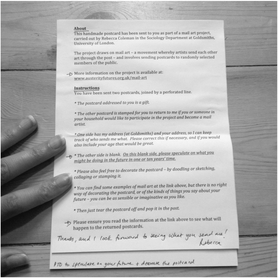

In one iteration of the project, I attempted to develop my own system of speculative shipping, drawing on mail art; an artistic movement aimed at creating international networks of artists based on gift rather than commercial exchange, and challenging distinctions between high and low culture in terms of what materials might be used in the practice. Using materials bought from Amazon as well as the packaging they were delivered in, I made postcards that I sent in the UK Royal Mail postal system to unsuspecting recipients, which I asked them to write and/or draw on and return to me (see Figures 1.6.2 and 1.6.3). In some ways then, the research created images, in that the postcards can be understood as collages which could be analysed both before they were mailed and after they were returned. They can therefore be treated as research data.

However, the broader aim of the project was to explore the implications of this imaging methodology for how images may be circulated. Would it be possible for this methodology to create a ‘delightful and exciting’ means of exchange between people who did not know each other? In many ways, the project failed: of the 26 postcards I sent, only one was returned to me – and it was left blank. However, in other ways, this failure enabled me to understand the imaging methodology I had deployed as ‘less a case of answering a pre-known research question [. . .] than a process of asking inventive [. . .] questions’ (Wilkie, Michael and Plummer-Fernandez 2014: 4). For example, I have asked, might sending unexpected packages in the post be unwelcome, rather than delightful and exciting? Are the postcards I made recognizable as gifts, in the ways that unexpected packages received from Amazon are? What happens when data are not produced in a research project in the way that they were designed to be?

Figure 1.6.2 Selection of postcards made

Figure 1.6.3 Outline of research and instructions included on postcards

Furthermore, the process of making the postcards led me to learn about mail art, and to consider how it might transform into a sociological method, which necessarily includes making decisions about research ethics. How might hitherto unknown participants of research be involved in circulating and disseminating research in ways that are ethical? What kinds of ethical questions regarding recruitment, inclusion, anonymity and ‘impact’ might this kind of research raise? Still further, presenting on this research project in different contexts has illuminated how boundaries between different disciplines remain monitored. Sociologists have asked me how the project is sociological: What are my data? How will I analyse them? What is my understanding of the social and the role of sociology in relation to the data? Artists have critiqued both my artistic skills and understanding of mail art.

This chapter has introduced some indicative cases of how imaging might be of value to a wider project of developing interdisciplinary methodologies. In terms of my second example, while the tone of some of the questioning around disciplinary boundaries has been dispiriting, the questions draw attention to both the difficulty of doing interdisciplinary work – what happens when methodology itself becomes that which is in focus in a project? What audience is the research engaging? – and the necessity of developing such interdisciplinary projects. For example, if Amazon’s speculative shipping might elicit feelings of delight and excitement, it seems reasonable to ask how social science research might provoke and engage such feelings. Would imaging be able to produce positive affects? Are text-based methods and modes of analysis most suitable to grasp what Les Back calls the ‘the fleeting, distributed, multiple, sensory, emotional and kinaesthetic aspects of sociality’ (2012: 28)? Questions emerging from the first example concern how images produced in imaging research might be disseminated, and relatedly, whether the production of such data requires the social sciences to move ‘beyond text’. Perhaps, as Puwar and Sharma (2012) argue, the social sciences might revive notions of curation, taking up practices more widespread in the arts, and requiring new forms of auditing to account for non-textual outputs.

Such questions indicate how interdisciplinary methodological practices might cultivate what, in a discussion of speculative design and sociology, Mike Michael calls the ‘common byways’ along which seemingly different and distinct methods, practices and approaches travel; ‘How can the engagements between these be rendered open, multiple, uncertain, playful?’ (Michael 2012: 177). Such engagements are necessary, I would suggest, in light of broader shifts that see methods as entangled with the becoming of the social world, and as a means of engaging both research participants and potential audiences in creative, meaningful and affectively enriching ways.

Back, L. (2012). Live sociology: social research and its futures. The Sociological Review, 60(S1): 18–39.

Coleman, R. (2009). The Becoming of Bodies: Girls, Images, Experience. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Coleman, R. (2016). Developing speculative methods to explore speculative shipping: mail art, futurity and empiricism. In A. Wilkie, M. Savransky and M. Rosengarten (Eds.) Speculative Research: The Lure of Possible Futures (pp. 130–144). London: Routledge.

Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F. (1987). A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. London and New York: Continuum.

Kopalle, P. (2014) ‘Why Amazon’s Anticipatory Shipping Is Pure Genius’. Forbes, 28 January 2014. Retrieved 16 February 2015 from www.forbes.com/sites/onmarketing/2014/01/28/why-amazons-anticipatory-shipping-is-pure-genius/

Michael, M. (2012). De-signing the object of sociology: toward an ‘idiotic’ methodology. The Sociological Review, 60(S1), 166–183.

Puwar, N. and Sharma, S. (2012). Curating sociology. The Sociological Review, 60(S1): 40–63.

Spiegel, J. et al. (2013) Method and system for anticipatory package shipping. United States Patent, 24 December 2013. Retrieved 16 February 2015 from http://patft.uspto.gov/netacgi/nph-Parser?Sect1=PTO1&Sect2=HITOFF&d=PALL&p=1&u=/netahtml/PTO/srchnum.htm&r=1&f=G&l=50&s1=8615473.PN.&OS=PN/8615473&RS=PN/8615473

Wilkie, A., Michael, M. and Plummer-Fernandez, M. (2014). Speculative method and Twitter: bots, energy and three conceptual characters. The Sociological Review, online first, 14.08.2014: 1–23.