• Worldwide, most adults acquire at least one sexually transmitted infection (STI).

• Three factors determine the initial rate of spread of any STI within a population: rate of sexual exposure of susceptible to infectious people, efficiency of transmission per exposure, and duration of infectivity of those infected.

• STI care and management begin with risk assessment and proceed to clinical assessment, diagnostic testing or screening, syndrome-based treatment to cover the most likely causes, and prevention and control. The “4 C’s” of control are contact tracing, ensuring compliance with treatment, and counseling on risk reduction, including condom promotion and provision.

Most cases are caused by either Neisseria gonorrhoeae or Chlamydia trachomatis. Other causative organisms include Mycoplasma genitalium, Ureaplasma urealyticum, Trichomonas vaginalis, and herpes simplex virus (HSV). Chlamydia causes 30–40% of nongonococcal urethritis (NGU) cases. M. genitalium is the probable cause in many Chlamydia-negative cases of NGU.

Urethritis in men produces urethral discharge, dysuria, or both, usually without frequency of urination.

Pts present with a mucopurulent urethral discharge that can usually be expressed by milking of the urethra; alternatively, a Gram’s-stained smear of urethral exudates containing ≥5 PMNs/1000× field confirms the diagnosis.

• Centrifuged sediment of the day’s first 20–30 mL of voided urine can be examined instead.

• N. gonorrhoeae can be presumptively identified if intracellular gram-negative diplococci are present in Gram’s-stained samples.

• Early-morning, first-voided urine should be used in “multiplex” nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) for N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis.

TREATMENT Urethritis in Men

• Treat urethritis promptly, while test results are pending.

– Unless these diseases have been excluded, treat gonorrhea with a single dose of ceftriaxone (250 mg IM), cefpodoxime (400 mg PO), or cefixime (400 mg PO) and treat Chlamydia with azithromycin (1 g PO once) or doxycycline (100 mg bid for 7 days); azithromycin may be more effective for M. genitalium.

– Sexual partners of the index case should receive the same treatment.

• For recurrent symptoms: With re-exposure, re-treat pt and partner. Without re-exposure, consider infection with T. vaginalis (with culture or NAATs of urethral swab and early-morning, first-voided urine) or doxycycline-resistant M. genitalium or Ureaplasma. Consider treatment with metronidazole, azithromycin (1 g PO once), or both.

In sexually active men <35 years old, epididymitis is caused by C. trachomatis and, less commonly, by N. gonorrhoeae.

• In older men or after urinary tract instrumentation, urinary pathogens are most common.

• In men who practice insertive rectal intercourse, Enterobacteriaceae may be responsible.

Acute epididymitis—almost always unilateral—produces pain, swelling, and tenderness of the epididymis, with or without symptoms or signs of urethritis. Epididymitis must be differentiated from testicular torsion, tumor, and trauma. If symptoms persist after treatment, a testicular tumor or a chronic granulomatous disease (e.g., tuberculosis) should be considered.

TREATMENT Epididymitis

• Ceftriaxone (250 mg IM once) followed by doxycycline (100 mg PO bid for 10 days) is effective for epididymitis due to C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae.

• Fluoroquinolones are no longer recommended because of increasing resistance in N. gonorrhoeae.

C. trachomatis, N. gonorrhoeae, and occasionally HSV cause symptomatic urethritis—known as the urethral syndrome in women—that is characterized by “internal” dysuria (usually without urinary urgency or frequency), pyuria, and an absence of Escherichia coli and other uropathogens at counts of ≥102/mL in urine.

Evaluate for infection with N. gonorrhoeae or C. trachomatis with specific tests (e.g., NAATs on the first 10 mL of voided morning urine).

TREATMENT Urethritis (the Urethral Syndrome) in Women

See “Urethritis in Men,” above.

A variety of organisms are associated with vulvovaginal infections, including N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis (particularly when they cause cervicitis), T. vaginalis, Candida albicans, Gardnerella vaginalis, and HSV.

Vulvovaginal infections encompass a wide array of specific conditions, each of which has different presenting symptoms.

• Unsolicited reporting of abnormal vaginal discharge suggests trichomoniasis or bacterial vaginosis (BV).

– Trichomoniasis is characterized by vulvar irritation and a profuse white or yellow, homogeneous vaginal discharge with a pH that is typically ≥5.

– BV is characterized by vaginal malodor and a slight to moderate increase in white or gray, homogeneous vaginal discharge that uniformly coats the vaginal walls and typically has a pH >4.5.

– Vaginal trichomoniasis and BV early in pregnancy are associated with premature onset of labor.

• Vulvar conditions such as genital herpes or vulvovaginal candidiasis can cause vulvar pruritus, burning, irritation, or lesions as well as external dysuria (as urine passes over the inflamed vulva or areas of epithelial disruption) or vulvar dyspareunia.

Evaluation of vulvovaginal symptoms includes a pelvic examination (with a speculum examination) and simple rapid diagnostic tests.

• Examine abnormal vaginal discharge for pH, a fishy odor after mixing with 10% KOH (BV), evidence on microscopy of motile trichomonads and/or clue cells of BV (vaginal epithelial cells coated with coccobacillary organisms) when mixed with saline, or hyphae or pseudohyphae on microscopy when 10% KOH is added (vaginal candidiasis).

• A DNA probe test (the Affirm test) can detect T. vaginalis, C. albicans, and increased concentrations of G. vaginalis.

TREATMENT Vulvovaginal Infections

• Vulvovaginal candidiasis: Miconazole (a single 1200-mg vaginal suppository), clotrimazole (two 100-mg vaginal tablets daily for 3 days), or fluconazole (150 mg PO once) are all effective.

• Trichomoniasis: Metronidazole (2 g PO once) or tinidazole is effective. Treatment of sexual partners with the same regimen is the standard of care.

• BV: Metronidazole (500 mg PO bid for 7 days) or 2% clindamycin cream (one full applicator vaginally each night for 7 days) is effective, but recurrence is common with both.

N. gonorrhoeae, C. trachomatis, and M. genitalium are the primary causative agents. Of note, NAATs for these pathogens, HSV, and T. vaginalis have been negative in nearly half of cases.

Mucopurulent cervicitis represents the “silent partner” of urethritis in men and results from inflammation of the columnar epithelium and subepithelium of the endocervix.

Yellow mucopurulent discharge from the cervical os, with ≥20 PMNs/1000×field on Gram’s stain of cervical mucus, indicates endocervicitis. The presence of intracellular gram-negative diplococci on Gram’s stain of cervical mucus is specific but <50% sensitive for gonorrhea; thus NAATs for N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis are always indicated.

See “Urethritis in Men,” above.

The agents most often implicated in acute PID—infection that ascends from the cervix or vagina to the endometrium and/or fallopian tubes—include the primary causes of endocervicitis (e.g., N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis); other organisms (e.g., M. genitalium, Prevotella spp., peptostreptococci, E. coli, Haemophilus influenzae, and group B streptococci) account for 25–33% of cases.

In 2008, there were 104,000 visits to physicians’ offices for PID in the United States; there are ~70,000–100,000 hospitalizations related to PID annually.

• Risk factors for PID include cervicitis, BV, a history of salpingitis or recent vaginal douching, menstruation, and recent insertion of an intrauterine contraceptive device (IUD).

• Oral contraceptive pills decrease risk.

The presenting symptoms depend on the extent to which the infection has spread.

• Endometritis: Pts present with midline abdominal pain and abnormal vaginal bleeding. Lower quadrant, adnexal, or cervical motion or abdominal rebound tenderness is less severe in women with endometritis alone than in women who also have salpingitis.

• Salpingitis: Symptoms evolve from mucopurulent cervicitis to endometritis and then to bilateral lower abdominal and pelvic pain caused by salpingitis. Nausea, vomiting, and increased abdominal tenderness may occur if peritonitis develops.

• Perihepatitis (Fitz-Hugh–Curtis syndrome): 3–10% of women present with pleuritic upper abdominal pain and tenderness in the right upper quadrant due to perihepatic inflammation. Most cases are due to chlamydial salpingitis.

• Periappendicitis: ~5% of pts can have appendiceal serositis without involvement of the intestinal mucosa as a result of gonococcal or chlamydial salpingitis.

Speculum examination shows evidence of mucopurulent cervicitis in the majority of pts with gonococcal or chlamydial PID; cervical motion tenderness, uterine fundal tenderness, and/or abnormal adnexal tenderness also are usually present. Endocervical swab specimens should be examined by NAATs for N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis.

• Empirical treatment for PID should be initiated in sexually active young women and in other women who are at risk for PID and who have pelvic or lower abdominal pain with no other explanation as well as cervical motion, uterine, or adnexal tenderness.

• Hospitalization should be considered when (1) the diagnosis is uncertain and surgical emergencies cannot be excluded, (2) the pt is pregnant, (3) pelvic abscess is suspected, (4) severe illness precludes outpatient management, (5) the pt has HIV infection, (6) the pt is unable to follow or tolerate an outpatient regimen, or (7) the pt has failed to respond to outpatient therapy.

• Outpatient regimen: Ceftriaxone (250 mg IM once) plus doxycycline (100 mg PO bid for 14 days) plus metronidazole (500 mg PO bid for 14 days) is effective. Women treated as outpatients should be clinically reevaluated within 72 h.

• Parenteral regimens: Parenteral treatment with regimens listed below should be given for ≥48 h after clinical improvement. A 14-day course should be completed with doxycycline (100 mg PO bid); if the clindamycin-containing regimen is used, oral therapy can be given with clindamycin (450 mg PO qid).

– Cefotetan (2 g IV q12h) or cefoxitin (2 g IV q6h) plus doxycycline (100 mg IV/PO q12h)

– Clindamycin (900 mg IV q8h) plus gentamicin (loading dose of 2.0 mg/kg IV/IM followed by 1.5 mg/kg q8h)

• Male sex partners should be evaluated and treated empirically for gonorrhea and chlamydial infection.

Late sequelae include infertility (11% after one episode of PID, 23% after two, and 54% after three or more); ectopic pregnancy (sevenfold increase in risk); chronic pelvic pain; and recurrent salpingitis.

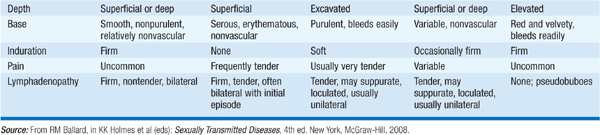

The most common etiologies in the United States are genital herpes, syphilis, and chancroid. See Table 92-1 and sections on individual pathogens below for specific clinical manifestations. Pts with persistent genital ulcers that do not resolve with syndrome-based antimicrobial therapy should have their HIV serologic status assessed if such testing has not previously been performed. Immediate treatment (before all test results are available) is often appropriate to improve response, reduce transmission, and cover pts who might not return for follow-up visits.

TABLE 92-1 CLINICAL FEATURES OF GENITAL ULCERS

Acquisition of HSV, N. gonorrhoeae, or C. trachomatis [including lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) strains of C. trachomatis] during receptive anorectal intercourse causes most cases of infectious proctitis in women and in men who have sex with men (MSM). Sexually acquired proctocolitis is most often due to Campylobacter or Shigella species. In MSM without HIV infection, enteritis is often attributable to Giardia lamblia.

Anorectal pain and mucopurulent, bloody rectal discharge suggest proctitis or proctocolitis. Proctitis is more likely to cause tenesmus and constipation, but proctocolitis and enteritis more often cause diarrhea.

• HSV proctitis and LGV proctocolitis can cause severe pain, fever, and systemic manifestations.

• Sacral nerve root radiculopathy, with urinary retention or anal sphincter dysfunction, is associated with primary HSV infection.

Pts should undergo anoscopy to examine the rectal mucosa and exudates and to obtain specimens for diagnosis.

TREATMENT Proctitis, Proctocolitis, Enterocolitis, Enteritis

• Pending test results, pts should receive empirical treatment for gonorrhea and chlamydial infection with ceftriaxone (125 mg IM once) followed by doxycycline (100 mg bid for 7 days); therapy for syphilis or herpes should be given as indicated.

N. gonorrhoeae, the causative agent of gonorrhea, is a gram-negative, nonmotile, non-spore-forming organism that grows singly and in pairs (i.e., as diplococci).

The ~299,000 cases reported in the United States in 2008 probably represent only half the true number of cases because of underreporting, self-treatment, and nonspecific treatment without a laboratory diagnosis.

• 40% of reported cases in the U.S. occur in 15- to 19-year-old women and 20- to 24-year-old men.

• Gonorrhea is transmitted from males to females more efficiently than in the opposite direction, with 40–60% of women acquiring gonorrhea during a single unprotected sexual encounter with an infected man. Roughly two-thirds of all infected men are asymptomatic.

• Drug-resistant strains are widespread. Penicillin, ampicillin, and tetracycline are no longer reliable therapeutic agents, and fluoroquinolones are no longer routinely recommended.

Except in disseminated disease, the sites of infection typically reflect areas involved in sexual contact.

• Urethritis and cervicitis have an incubation period of 2–7 days and ~10 days, respectively. See above for details.

• Anorectal gonorrhea can cause acute proctitis in women (due to the spread of cervical exudate to the rectum) and MSM.

• Pharyngeal gonorrhea is usually mild or asymptomatic and results from oral-genital sexual exposure (typically fellatio). Pharyngeal infection almost always coexists with genital infection, resolves spontaneously, and is rarely transmitted to sexual contacts.

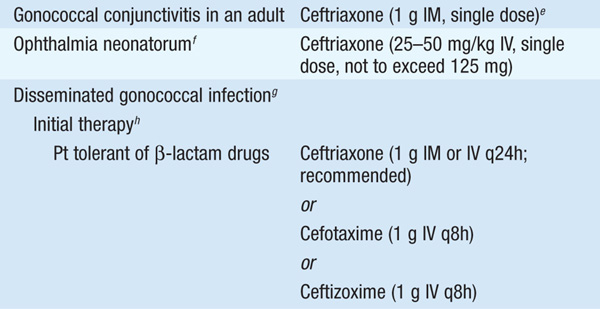

• Ocular gonorrhea is typically caused by autoinoculation and presents with a markedly swollen eyelid, hyperemia, chemosis, and profuse purulent discharge.

• Gonorrhea in pregnancy can have serious consequences for both the mother and the infant.

– Salpingitis and PID are associated with fetal loss.

– Third-trimester disease can cause prolonged rupture of membranes, premature delivery, chorioamnionitis, funisitis, and neonatal sepsis.

– Ophthalmia neonatorum, the most common form of gonorrhea among neonates, is preventable by prophylactic ophthalmic ointments (e.g., containing erythromycin or tetracycline), but treatment requires systemic antibiotics.

• Gonococcal arthritis results from dissemination of organisms due to gonococcal bacteremia. Pts present during a bacteremic phase (relatively uncommon) or with suppurative arthritis involving one or two joints (most commonly the knees, wrists, ankles, and elbows), with tenosynovitis and skin lesions. Menstruation and complement deficiencies of the membrane attack complex (C5–C9) are risk factors for disseminated disease.

NAATs, culture, and microscopic examination (for intracellular diplococci) of urogenital samples are used to diagnose gonorrhea. A single culture of endocervical discharge has a sensitivity of 80–90%.

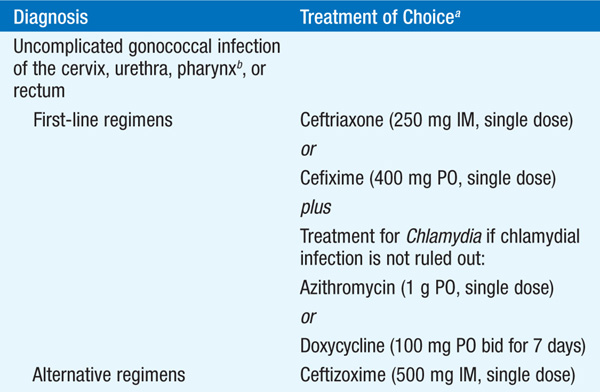

TREATMENT Gonorrhea

See Table 92-2.

TABLE 92-2 RECOMMENDED TREATMENT FOR GONOCOCCAL INFECTIONS: 2010 GUIDELINES OF THE CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION

C. trachomatis organisms are obligate intracellular bacteria that are divided into two biovars: trachoma and LGV. The trachoma biovar causes ocular trachoma and urogenital infections; the LGV biovar causes lymphogranuloma venereum.

The WHO estimates that >89 million cases of C. trachomatis infection occur annually worldwide. The estimated 2–3 million cases per year that occur in the U.S. make C. trachomatis infection the most commonly reported infectious disease in this country.

80–90% of women and >50% of men with C. trachomatis genital infections lack symptoms; other pts have very mild symptoms.

• Urethritis, epididymitis, cervicitis, salpingitis, PID, and proctitis are all discussed above.

• Reactive arthritis (conjunctivitis, urethritis or cervicitis, arthritis, and mucocutaneous lesions) occurs in 1–2% of NGU cases, many of which are due to C. trachomatis. More than 80% of pts have the HLA-B27 phenotype.

• LGV is an invasive, systemic STI that—in heterosexual individuals—presents most commonly as painful inguinal lymphadenopathy beginning 2–6 weeks after presumed exposure. Progressive periadenitis results in fluctuant, suppurative nodes with development of multiple draining fistulas. Spontaneous resolution occurs after several months. See Table 92-1 for additional clinical details.

NAATs of urine or urogenital swabs are the diagnostic tests of choice. Serologic testing may be helpful in the diagnosis of LGV and neonatal pneumonia caused by C. trachomatis, but it is not useful in diagnosing uncomplicated urogenital infections.

• See “Specific Syndromes,” above.

• LGV should be treated with doxycycline (100 mg PO bid) or erythromycin base (500 mg PO qid) for at least 3 weeks.

Mycoplasmas are the smallest free-living organisms known and lack a cell wall. M. hominis, M. genitalium, Ureaplasma parvum, and U. urealyticum cause urogenital tract disease. These organisms are commonly present in the vagina of asymptomatic women.

Ureaplasmas are a common cause of Chlamydia-negative NGU. M. hominis and M. genitalium are associated with PID; M. hominis is implicated in 5–10% of cases of postpartum or postabortal fever.

PCR is most commonly used for detection of urogenital mycoplasmas; culture is possible but can be done primarily at reference laboratories. Serologic testing is not helpful.

TREATMENT Infections Due to Mycoplasmas

Recommendations for treatment of NGU and PID listed above are appropriate for genital mycoplasmas.

Treponema pallidum subspecies pallidum—the cause of syphilis—is a thin spiral organism with a cell body surrounded by a trilaminar cytoplasmic membrane. Humans are the only natural host, and the organism cannot be cultured in vitro.

• Cases are acquired by sexual contact with infectious lesions (chancre, mucous patch, skin rash, condyloma latum); nonsexual acquisition through close personal contact, infection in utero, blood transfusion, and organ transplantation is less common.

• There are ~12 million new infections per year worldwide.

– In the United States, 31,575 cases were reported in 2000.

– The reported cases of primary and secondary syphilis combined (which better indicate disease activity) increased from <6000 in 2000 to 13,500 in 2008, primarily affecting MSM, many of whom were co-infected with HIV.

• One-third to one-half of sexual contacts of persons with infectious syphilis become infected—a figure that underscores the importance of treating all recently exposed sexual contacts.

T. pallidum penetrates intact mucous membranes or microscopic abrasions and, within hours, enters lymphatics and blood to produce systemic infection and metastatic foci. The primary lesion (chancre) appears at the site of inoculation within 4–6 weeks and heals spontaneously. Generalized parenchymal, constitutional, and mucocutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis appear 6–8 weeks later despite high antibody titers, subsiding in 2–6 weeks. After a latent period, one-third of untreated pts eventually develop tertiary disease (syphilitic gummas, cardiovascular disease, neurologic disease).

Syphilis progresses through three phases with distinct clinical presentations.

• Primary syphilis: A chancre at the site of inoculation (penis, rectum or anal canal, mouth, cervix, labia) is characteristic but often goes unnoticed. See Table 92-1 for clinical details. Regional adenopathy can persist long after the chancre heals.

• Secondary syphilis: The protean manifestations of the secondary stage usually include mucocutaneous lesions and generalized nontender lymphadenopathy.

– Skin lesions can be subtle but are often pale red or pink, nonpruritic macules that are widely distributed over the trunk and extremities, including the palms and soles.

– In moist intertriginous areas, papules can enlarge and erode to produce broad, highly infectious lesions called condylomata lata.

– Superficial mucosal erosions (mucous patches) and constitutional symptoms (e.g., sore throat, fever, malaise) can occur.

– Less common findings include hepatitis, nephropathy, arthritis, and ocular findings (e.g., optic neuritis, anterior uveitis, iritis).

• Latent syphilis: Pts without clinical manifestations but with positive syphilis serology have latent disease. Early latent syphilis is limited to the first year after infection, whereas late latent syphilis is defined as that of ≥1 year’s (or unknown) duration.

• Tertiary syphilis: The classic forms of tertiary syphilis include neurosyphilis, cardiovascular syphilis, and gummas.

– Neurosyphilis represents a continuum, with asymptomatic disease occurring early after infection, potentially progressing to general paresis and tabes dorsalis. Symptomatic disease has three main presentations, all of which are now rare (except in pts with advanced HIV infection). Meningeal syphilis presents as headache, nausea, vomiting, neck stiffness, cranial nerve involvement, seizures, and changes in mental status within 1 year of infection. Meningovascular syphilis presents up to 10 years after infection as a subacute encephalitic prodrome followed by a gradually progressive vascular syndrome. Parenchymatous involvement presents at 20 years for general paresis and 25–30 years for tabes dorsalis. A general mnemonic for paresis is personality, affect, reflexes (hyperactive), eye (Argyll Robertson pupils, which react to accommodation but not to light), sensorium (illusions, delusions, hallucinations), intellect (decrease in recent memory and orientation, judgment, calculations, insight), and speech. Tabes dorsalis is a demyelination of posterior columns, dorsal roots, and dorsal root ganglia, with ataxic, wide-based gait and footslap; paresthesia; bladder disturbances; impotence; areflexia; and loss of position, deep pain, and temperature sensations.

– Cardiovascular syphilis develops in ~10% of untreated pts 10–40 years after infection. Endarteritis obliterans of the vasa vasorum providing the blood supply to large vessels results in aortitis, aortic regurgitation, saccular aneurysm, and coronary ostial stenosis.

– Gummas are usually solitary lesions showing granulomatous inflammation with central necrosis. Common sites include the skin and skeletal system; however, any organ (including the brain) may be involved.

• Congenital syphilis: Syphilis can be transmitted throughout pregnancy, but fetal disease does not become manifest until after the fourth month of gestation. All pregnant women should be tested for syphilis early in pregnancy.

Serologic tests—both nontreponemal and treponemal—are the mainstays of diagnosis; changes in antibody titers can also be used to monitor response to therapy.

• Nontreponemal serologic tests that measure IgG and IgM antibodies to a cardiolipin-lecithin-cholesterol antigen complex [e.g., rapid plasma reagin (RPR), Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL)] are recommended for screening or for quantitation of serum antibody. After therapy for early syphilis, a persistent fall in titer by ≥4-fold is considered an adequate response.

• Treponemal tests, including the agglutination assay (e.g., the Serodia TP-PA test) and the fluorescent treponemal antibody–absorbed (FTA-ABS) test, are used to confirm results from nontreponemal tests. Results remain positive even after successful treatment.

• Lumbar puncture (LP) is recommended for pts with syphilis and neurologic signs or symptoms, an RPR or VDRL titer ≥1:32, or suspected treatment failure and for HIV-infected pts with a CD4+ T cell count <350/μL.

– CSF exam demonstrates pleocytosis (>5 WBCs/μL) and increased protein levels (>45 mg/dL). A positive CSF VDRL test is specific but not sensitive; an unabsorbed FTA test is sensitive but not specific. A negative unabsorbed FTA test excludes neurosyphilis.

• Pts with syphilis should be evaluated for HIV disease.

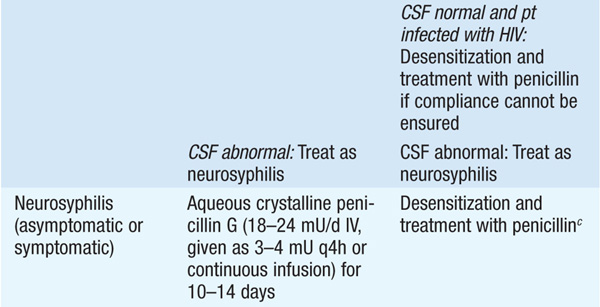

TREATMENT Syphilis

• See Table 92-3 for treatment recommendations.

TABLE 92-3 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE TREATMENT OF SYPHILISa

• The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction is a dramatic reaction to treatment that is most common with initiation of therapy for primary (~50% of pts) or secondary (~90%) syphilis. The reaction is associated with fever, chills, myalgias, tachycardia, headache, tachypnea, and vasodilation. Symptoms subside within 12–24 h without treatment.

• Response to treatment should be monitored by determination of RPR or VDRL titers at 6 and 12 months in primary and secondary syphilis and at 6, 12, and 24 months in tertiary or latent syphilis.

– HIV-infected pts should undergo repeat serologic testing at 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 months, irrespective of the stage of syphilis.

– Re-treatment should be considered if serologic responses are not adequate (a persistent fall by ≥4-fold) or if clinical signs persist or recur. For these pts, CSF should be examined, with treatment for neurosyphilis if CSF is abnormal and treatment for late latent syphilis if CSF is normal.

– In treated neurosyphilis, CSF cell counts should be monitored every 6 months until normal. In adequately treated HIV-uninfected pts, an elevated CSF cell count falls to normal in 3–12 months.

HSV is a linear, double-strand DNA virus, with two subtypes (HSV-1 and HSV-2).

• Exposure to HSV at mucosal surfaces or abraded skin sites permits viral entry into cells of the epidermis and dermis, viral replication, entry into neuronal cells, and centrifugal spread throughout the body.

• More than 90% of adults have antibodies to HSV-1 by age 40; 15–20% of the U.S. population has antibodies to HSV-2.

• Unrecognized carriage of HSV-2 and frequent asymptomatic reactivations of virus from the genital tract foster the continued spread of HSV disease.

• Genital lesions caused by HSV-1 have lower recurrence rates in the first year (~55%) than those caused by HSV-2 (~90%).

See Table 92-1 for clinical details. First episodes of genital herpes due to HSV-1 and HSV-2 present similarly and can be associated with fever, headache, malaise, and myalgias. More than 80% of women with primary genital herpes have cervical or urethral involvement. Local symptoms include pain, dysuria, vaginal and urethral discharge, and tender inguinal lymphadenopathy.

Isolation of HSV in tissue culture or demonstration of HSV antigens or DNA in scrapings from lesions is the most accurate diagnostic method. PCR is increasingly being used for detection of HSV DNA and is more sensitive than culture at mucosal sites. Staining of scrapings from the base of the lesion with Wright’s, Giemsa’s (Tzanck preparation), or Papanicolaou’s stain to detect giant cells or intranuclear inclusions is well described, but most clinicians are not skilled in these techniques, which furthermore do not differentiate between HSV and VZV.

• First episodes: Oral acyclovir (400 mg tid), valacyclovir (1 g bid), or famciclovir (250 mg bid) for 7–14 days is effective.

• Symptomatic recurrent episodes: Oral acyclovir (800 mg tid for 2 days), valacyclovir (500 mg bid for 3 days), or famciclovir (750 or 1000 mg bid for 1 day, 1500 mg once, or 500 mg stat followed by 250 mg q12h for 3 days) effectively shortens lesion duration.

• Suppression of recurrent episodes: Oral acyclovir (400–800 mg bid) or valacyclovir (500 mg qd) is given. Pts with >9 episodes per year should take valacyclovir (1 g qd or 500 mg bid) or famciclovir (250–500 mg bid). Daily valacyclovir appears to be more effective at reducing subclinical shedding than daily famciclovir.

H. ducreyi is the etiologic agent of chancroid, an STI characterized by genital ulceration and inguinal adenitis. H. ducreyi poses a significant health problem in developing countries because of its directly related morbidity and its role in increasing the efficiency of transmission of and degree of susceptibility to HIV infection. See Table 92-1 for clinical details. Culture of H. ducreyi from the lesion confirms the diagnosis; PCR is starting to become available.

TREATMENT Chancroid (Haemophilus ducreyi Infection)

• Regimens recommended by the CDC include azithromycin (1 g PO once), ciprofloxacin (500 mg PO bid for 3 days), ceftriaxone (250 mg IM once), and erythromycin base (500 mg tid for 1 week).

• Sexual partners within 10 days preceding the pt’s onset of symptoms should be identified and treated, regardless of symptoms.

Also known as granuloma inguinale, donovanosis is caused by Klebsiella granulomatis. The infection is endemic in Papua New Guinea, parts of southern Africa, India, French Guyana, Brazil, and aboriginal communities in Australia; few cases are reported in the U.S.

See Table 92-1 for clinical details. Four types of lesions have been described: (1) the classic ulcerogranulomatous lesion that bleeds readily when touched; (2) a hypertrophic or verrucous ulcer with a raised irregular edge; (3) a necrotic, offensive-smelling ulcer causing tissue destruction; and (4) a sclerotic or cicatricial lesion with fibrous and scar tissue. The genitals are affected in 90% of pts and the inguinal region in 10%.

Diagnosis is often based on identification of typical Donovan bodies (gram-negative intracytoplasmic cysts filled with deeply staining bodies that may have a safety-pin appearance) within large mononuclear cells in smears from lesions or biopsy specimens. PCR is also available. Pts should be treated with azithromycin (1 g on day 1, then 500 mg qd for 7 days or 1 g weekly for 4 weeks); alternative therapy consists of a 14-day course of doxycycline (100 mg bid), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (960 mg bid), erythromycin (500 mg qid), or tetracycline (500 mg qid). If any of the 14-day treatment regimens are chosen, the pts should be monitored until lesions have healed completely.

Papillomaviruses are nonenveloped viruses with a double-strand circular DNA genome. More than 100 HPV types are recognized, and individual types are associated with specific clinical manifestations. For example, HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, and 45 have been most strongly associated with cervical cancers, and HPV types 6 and 11 cause anogenital warts (condylomata acuminata). Most infections, including those with oncogenic types, are self-limited.

The clinical manifestations of HPV infection depend on the location of lesions and the type of virus. The incubation period is usually 3–4 months but can be as long as 2 years.

• Warts (including plantar warts) appear as flesh-colored to brown and exophytic, with hyperkeratotic papules.

• Anogenital warts are commonly found on the penile shaft (in circumcised men), at the urethral meatus, and in the perianal region (in persons who practice receptive anal intercourse) and may involve the vagina and cervix.

Most visible warts are diagnosed correctly by history and physical examination alone. Colposcopy is invaluable in assessing vaginal and cervical lesions, and 3–5% acetic acid solution applied to lesions may aid in the diagnosis.

• Papanicolaou smears from cervical or anal scrapings show cytologic evidence of HPV infection.

• Detection of HPV nucleic acids (e.g., PCR, hybrid-capture assay) is the most specific and sensitive method of detection.

TREATMENT Human Papillomavirus Infections

• Many lesions resolve spontaneously. Current treatment is not completely effective, and some agents have significant side effects.

– Provider-administered therapy can include cryotherapy, podophyllin resin (10–25%) applied weekly for up to 4 weeks, trichloroacetic acid or bichloroacetic acid (80–90%) applied weekly, surgical excision, intralesionally administered interferon, or laser surgery.

– Pt-administered therapy consists of podofilox (0.5% solution or gel applied bid for 3 days; this treatment can be repeated up to 4 times with 4 days between treatment courses) or imiquimod (5% cream applied 3 times/week for up to 16 weeks).

A quadrivalent vaccine (Gardasil, Merck) containing HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18 and a bivalent vaccine (Cervarix, GlaxoSmithKline) containing HPV types 16 and 18 are available. Either vaccine is recommended for administration to girls and young women 9–26 years of age and may be used in males 9–26 years of age.

• HPV types 6 and 11 cause 90% of anogenital warts, and HPV types 16 and 18 cause 70% of cervical cancers.

• Because 30% of cervical cancers are caused by HPV types not included in either vaccine, no changes in clinical cancer-screening programs are currently recommended.

For a more detailed discussion, see Marrazzo JM, Holmes KK: Sexually Transmitted Infections: Overview and Clinical Approach, Chap. 130, p. 1095; Ram S, Rice PA: Gonococcal Infections, Chap. 144, p. 1220; Murphy TF: Haemophilus and Moraxella Infections, Chap. 145, p. 1228; O’Farrell N: Donovanosis, Chap. 161, p. 1320; Lukehart SA: Syphilis, Chap. 169, p. 1380; Hardy RD: Infections Due to Mycoplasmas, Chap. 175, p. 1417; Gaydos CA, Quinn TC: Chlamydial Infections, Chap. 176, p. 1421; Corey L: Herpes Simplex Virus Infections, Chap. 179, p. 1453; and Reichman RC: Human Papillomavirus Infections, Chap. 185, p. 1481, in HPIM-18.