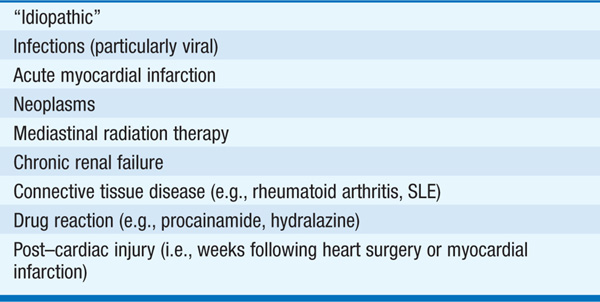

TABLE 125-1 MOST COMMON CAUSES OF PERICARDITIS

Chest pain, which may be intense, mimicking acute MI, but characteristically sharp, pleuritic, and positional (relieved by leaning forward); fever and palpitations are common. Typical pain may not be present in slowly developing pericarditis (e.g., tuberculous, post-irradiation, neoplastic, uremic).

Rapid or irregular pulse, coarse pericardial friction rub, which may vary in intensity and is loudest with pt sitting forward.

FIGURE 125-1 Electrocardiogram in acute pericarditis. Note diffuse ST-segment elevation and PR-segment depression.

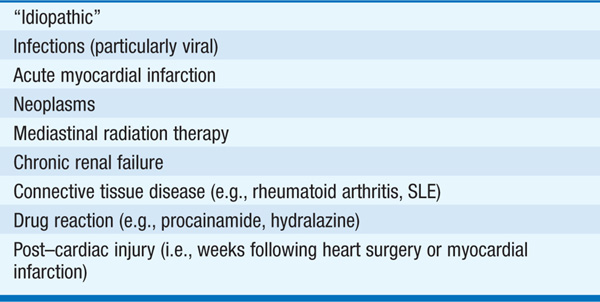

TABLE 125-2 ECG IN ACUTE PERICARDITIS VS ACUTE ST-ELEVATION MI

Diffuse ST elevation (concave upward) usually present in all leads except aVR and V1; PR-segment depression (and/or PR elevation in lead aVR) may be present; days later (unlike acute MI), ST returns to baseline and T-wave inversion develops. Atrial premature beats and atrial fibrillation may appear. Differentiate from ECG of early repolarization (ER) (ratio of ST elevation/T wave height <0.25 in ER, but >0.25 in pericarditis).

Symmetrically increased size of cardiac silhouette if large (>250 mL) pericardial effusion is present.

Most readily available test for detection of pericardial effusion, which commonly accompanies acute pericarditis.

Aspirin 650–975 mg qid or other NSAIDs (e.g., ibuprofen 400–600 mg tid or indomethacin 25–50 mg tid); addition of colchicine 0.6 mg bid may be beneficial and reduces frequency of recurrences. For severe, refractory pain, prednisone 40–80 mg/d can be used as last resort. Intractable, prolonged pain or frequently recurrent episodes may require pericardiectomy. Anticoagulants are relatively contraindicated in acute pericarditis because of risk of pericardial hemorrhage.

Life-threatening condition resulting from accumulation of pericardial fluid under pressure; impaired filling of cardiac chambers and decreased cardiac output.

Previous pericarditis (most commonly metastatic tumor, uremia, viral or idiopathic pericarditis), cardiac trauma, or myocardial perforation during catheter or pacemaker placement.

Hypotension may develop suddenly; subacute symptoms include dyspnea, weakness, confusion.

Tachycardia, hypotension, pulsus paradoxus (inspiratory fall in systolic blood pressure >10 mmHg), jugular venous distention with preserved x descent but loss of y descent; heart sounds distant. If tamponade develops subacutely, peripheral edema, hepatomegaly, and ascites may be present.

Low limb lead voltage; large effusions may cause electrical alternans (alternating size of QRS complex due to swinging of heart).

Enlarged cardiac silhouette if large (>250 mL) effusion present.

Swinging motion of heart within large effusion; prominent respiratory alteration of RV dimension with RA and RV collapse during diastole. Doppler shows marked respiratory variation of transvalvular flow velocities.

Confirms diagnosis; shows equalization of diastolic pressures in all four chambers; pericardial = RA pressure.

TREATMENT Cardiac Tamponade

Immediate pericardiocentesis and IV volume expansion.

Condition in which a rigid pericardium impairs cardiac filling, causing elevation of systemic and pulmonary venous pressures, and decreased cardiac output. Results from healing and scar formation in some pts with previous pericarditis. Viral, tuberculosis (mostly in developing nations), previous cardiac surgery, collagen vascular disorders, uremia, neoplastic and radiation-associated pericarditis are potential causes.

Gradual onset of dyspnea, fatigue, pedal edema, abdominal swelling; symptoms of LV failure uncommon.

Tachycardia, jugular venous distention (with prominent y descent) that increases further on inspiration (Kussmaul sign); hepatomegaly, ascites, peripheral edema are common; sharp diastolic sound, “pericardial knock” following S2 sometimes present.

Low limb lead voltage; atrial arrhythmias are common.

Rim of pericardial calcification is most common in tuberculous pericarditis.

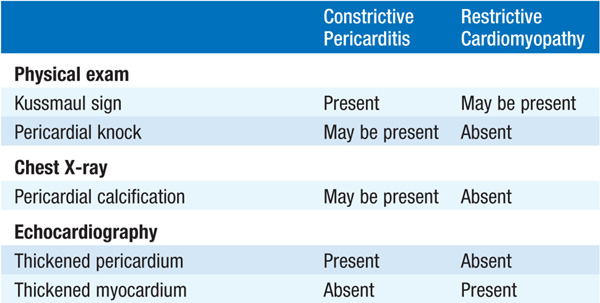

Thickened pericardium, normal ventricular contraction; abrupt halt in ventricular filling in early diastole. Dilatation of IVC is common. Dramatic effects of respiration are typical: During inspiration the ventricular septum shifts to the left with prominent reduction of blood flow velocity across mitral valve; pattern reverses during expiration (Fig 125-2).

FIGURE 125-2 Constrictive pericarditis. Doppler schema of respirophasic changes in mitral and tricuspid inflow. Reciprocal patterns of ventricular filling are assessed on pulsed Doppler examination of mitral (MV) and tricuspid (TV) inflow. (Courtesy of Bernard E. Bulwer, MD; with permission.)

More precise than echocardiogram for demonstrating thickened pericardium.

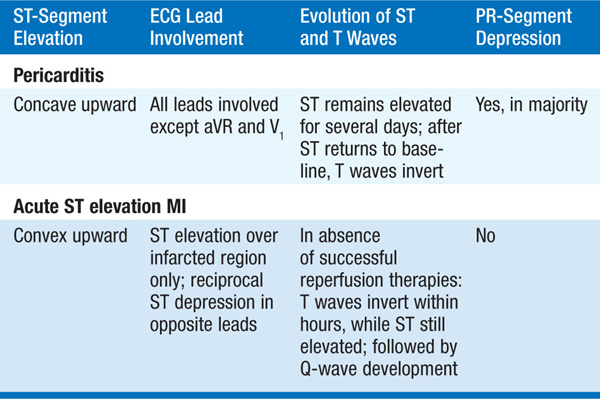

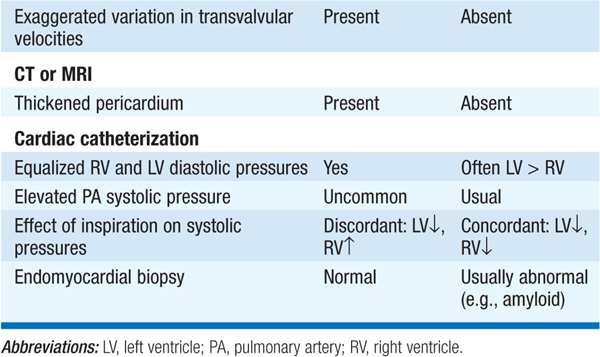

Equalization of diastolic pressures in all chambers; ventricular pressure tracings show “dip and plateau” appearance. Differentiate from restrictive cardiomyopathy (Table 125-3).

TABLE 125-3 FEATURES THAT DIFFERENTIATE CONSTRICTIVE PERICARDITIS FROM RESTRICTIVE CARDIOMYOPATHY

TREATMENT Constrictive Pericarditis

Surgical stripping of the pericardium. Progressive improvement ensues over several months.

If careful history and physical exam do not suggest etiology, the following may lead to diagnosis:

• Skin test and cultures for tuberculosis (Chap. 103)

• Serum albumin and urine protein measurement (nephrotic syndrome)

• Serum creatinine and BUN (renal failure)

• Thyroid function tests (myxedema)

• Antineutrophil antibodies (SLE and other collagen-vascular disease)

• Search for a primary tumor (especially lung and breast)

For a more detailed discussion, see Braunwald E: Pericardial Disease, Chap. 239, p. 1971, in HPIM-18.