The pituitary hormones, luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), stimulate ovarian follicular development and result in ovulation at about day 14 of the 28-day menstrual cycle.

Amenorrhea refers to the absence of menstrual periods. It is classified as primary, if menstrual bleeding has never occurred by age 15 in the absence of hormonal treatment, or secondary, if menstrual periods are absent for >3 months in a woman with previous periodic menses. Pregnancy should be excluded in women of childbearing age with amenorrhea, even when history and physical exam are not suggestive. Oligomenorrhea is defined as a cycle length of >35 days or <10 menses per year. Both the frequency and amount of bleeding are irregular in oligomenorrhea. Frequent or heavy irregular bleeding is termed dysfunctional uterine bleeding if anatomic uterine lesions or a bleeding diathesis have been excluded.

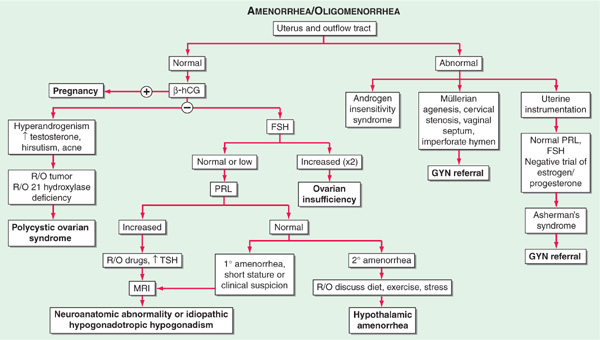

The causes of primary and secondary amenorrhea overlap, and it is generally more useful to classify disorders of menstrual function into disorders of the uterus and outflow tract and disorders of ovulation (Fig. 186-1).

FIGURE 186-1 Algorithm for evaluation of amenorrhea. β-hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; PRL, prolactin; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Anatomic defects of the outflow tract that prevent vaginal bleeding include absence of vagina or uterus, imperforate hymen, transverse vaginal septae, and cervical stenosis.

Women with amenorrhea and low FSH and LH levels have hypogonadotropic hypogonadism due to disease of either the hypothalamus or the pituitary. Hypothalamic causes include congenital idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, hypothalamic lesions (craniopharyngiomas and other tumors, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, metastatic tumors), hypothalamic trauma or irradiation, vigorous exercise, eating disorders, stress, and chronic debilitating diseases (end-stage renal disease, malignancy, malabsorption). The most common form of hypothalamic amenorrhea is functional, reversible GnRH deficiency due to psychological or physical stress, including excess exercise and anorexia nervosa. Disorders of the pituitary include rare developmental defects, pituitary adenomas, granulomas, post-radiation hypopituitarism, and Sheehan’s syndrome. They can lead to amenorrhea by two mechanisms: direct interference with gonadotropin production, or inhibition of GnRH secretion via excess prolactin production (Chap. 179).

Women with amenorrhea and high FSH levels have ovarian failure, which may be due to Turner’s syndrome, pure gonadal dysgenesis, premature ovarian failure, the resistant-ovary syndrome, and chemotherapy or radiation therapy for malignancy. The diagnosis of premature ovarian failure is applied to women who cease menstruating before age 40.

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is characterized by the presence of clinical or biochemical hyperandrogenism (hirsutism, acne, male pattern baldness) in association with amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea. The metabolic syndrome and infertility are often present; these features are worsened with coexistent obesity. Additional disorders with a similar presentation include excess androgen production from adrenal or ovarian tumors and adult-onset congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Hyperthyroidism may be associated with oligo- or amenorrhea; hypothyroidism more typically with metrorrhagia.

The initial evaluation involves careful physical exam including assessment of hyperandrogenism, serum or urine human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), and serum FSH levels (Fig. 186-1). Anatomic defects are usually diagnosed by physical exam, though hysterosalpingography or direct visual examination by hysteroscopy may be required. A karyotype should be performed when gonadal dysgenesis is suspected. The diagnosis of PCOS is based on the coexistence of chronic anovulation and androgen excess, after ruling out other etiologies for these features. The evaluation of pituitary function and hyperprolactinemia is described in Chap. 179. In the absence of a known etiology for hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, MRI of the pituitary-hypothalamic region should be performed when gonadotropins are low or inappropriately normal.

TREATMENT Amenorrhea

Disorders of the outflow tract are managed surgically. Decreased estrogen production, whether from ovarian failure or hypothalamic/pituitary disease, should be treated with cyclic estrogens, either in the form of oral contraceptives or conjugated estrogens (0.625–1.25 mg/d PO) and medroxyprogesterone acetate (2.5 mg/d PO or 5–10 mg during the last 5 days of the month). PCOS may be treated with medications to induce periodic withdrawal menses (medroxyprogesterone acetate 5–10 mg or progesterone 200 mg daily for 10–14 days of each month, or oral contraceptive agents) and weight reduction, along with treatment of hirsutism and, if desired, ovulation induction (see below). Individuals with PCOS may benefit from insulin-sensitizing drugs, such as metformin, and should be screened for diabetes mellitus.

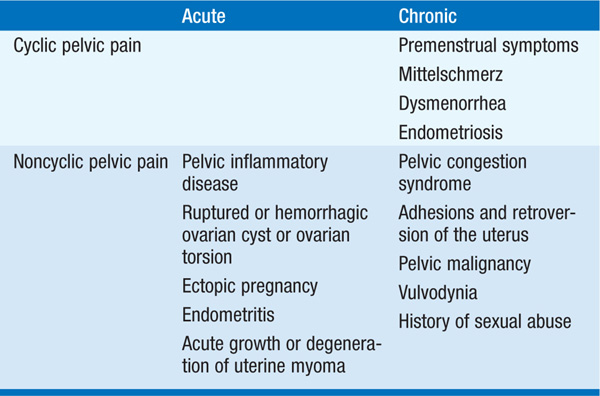

Pelvic pain may be associated with normal or abnormal menstrual cycles and may originate in the pelvis or be referred from another region of the body. A high index of suspicion must be entertained for extrapelvic disorders that refer to the pelvis, such as appendicitis, diverticulitis, cholecystitis, intestinal obstruction, and urinary tract infections. A thorough history including the type, location, radiation, and status with respect to increasing or decreasing severity can help to identify the cause of acute pelvic pain. Associations with vaginal bleeding, sexual activity, defecation, urination, movement, or eating should be sought. Determination of whether the pain is acute versus chronic, constant versus spasmodic, and cyclic versus noncyclic will direct further investigation (Table 186-1).

TABLE 186-1 CAUSES OF PELVIC PAIN

Pelvic inflammatory disease most commonly presents with bilateral lower abdominal pain. Unilateral pain suggests adnexal pathology from rupture, bleeding, or torsion of ovarian cysts, or, less commonly, neoplasms of the ovary, fallopian tubes, or paraovarian areas. Ectopic pregnancy is associated with right- or left-sided lower abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding, and menstrual cycle abnormalities, with clinical signs appearing 6–8 weeks after the last normal menstrual period. Orthostatic signs and fever may be present. Uterine pathology includes endometritis and degenerating leiomyomas.

Many women experience lower abdominal discomfort with ovulation (mittelschmerz), characterized as a dull, aching pain at midcycle that lasts minutes to hours. In addition, ovulatory women may experience somatic symptoms during the few days prior to menses, including edema, breast engorgement, and abdominal bloating or discomfort. A symptom complex of cyclic irritability, depression, and lethargy is known as premenstrual syndrome (PMS). Severe or incapacitating cramping with ovulatory menses in the absence of demonstrable disorders of the pelvis is termed primary dysmenorrhea. Secondary dysmenorrhea is caused by underlying pelvic pathology such as endometriosis, adenomyosis, or cervical stenosis.

Evaluation includes a history, pelvic exam, hCG measurement, tests for chlamydial and gonococcal infections, and pelvic ultrasound. Laparoscopy or laparotomy is indicated in some cases of pelvic pain of undetermined cause.

TREATMENT Pelvic Pain

Primary dysmenorrhea is best treated with NSAIDs or oral contraceptive agents. Secondary dysmenorrhea not responding to NSAIDs suggests pelvic pathology, such as endometriosis. Infections should be treated with the appropriate antibiotics. Symptoms from PMS may improve with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) therapy. The majority of unruptured ectopic pregnancies are treated with methotrexate, which has an 85–95% success rate. Surgery may be required for structural abnormalities.

Hirsutism, defined as excessive male-pattern hair growth, affects ~10% of women. It may be familial or caused by PCOS, ovarian or adrenal neoplasms, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, Cushing’s syndrome, pregnancy, and drugs (androgens, oral contraceptives containing androgenic proges-tins). Other drugs, such as minoxidil, phenytoin, diazoxide, and cyclosporine, can cause excessive growth of non-androgen-dependent vellus hair, leading to hypertrichosis.

An objective clinical assessment of hair distribution and quantity is central to the evaluation. A commonly used method to grade hair growth is the Ferriman-Gallwey score (see Fig. 49-1, p. 382, in HPIM-18). Associated manifestations of androgen excess include acne and male-pattern balding (androgenic alopecia). Virilization, on the other hand, refers to the state in which androgen levels are sufficiently high to cause deepening of the voice, breast atrophy, increased muscle bulk, clitoromegaly, and increased libido. Historic elements include menstrual history and the age of onset, rate of progression, and distribution of hair growth. Sudden development of hirsutism, rapid progression, and virilization suggest an ovarian or adrenal neoplasm.

An approach to testing for androgen excess is depicted in Fig. 186-2. PCOS is a relatively common cause of hirsutism. The dexamethasone androgen-suppression test (0.5 mg PO every 6 h × 4 days, with free testosterone levels obtained before and after administration of dexamethasone) may distinguish ovarian from adrenal overproduction. Incomplete suppression suggests ovarian androgen excess. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency can be excluded by a 17-hydroxyprogesterone level that is <6 nmol/L (<2 μg/L) either in the morning during the follicular phase or 1 h after administration of 250 μg of cosyntropin. CT may localize an adrenal mass, and ultrasound may identify an ovarian mass, if evaluation suggests these possibilities.

FIGURE 186-2 Algorithm for the evaluation and differential diagnosis of hirsutism. ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; CAH, congenital adrenal hyperplasia; DHEAS, sulfated form of dehydroepiandrosterone; PCOS, polycystic ovarian syndrome.

Treatment of a remediable underlying cause (e.g., Cushing’s syndrome, adrenal or ovarian tumor) also improves hirsutism. In idiopathic hirsutism or PCOS, symptomatic physical or pharmacologic treatment is indicated. Nonpharmacologic treatments include (1) bleaching; (2) depilatory such as shaving and chemical treatments; and (3) epilatory such as plucking, waxing, electrolysis, and laser therapy. Pharmacologic therapy includes oral contraceptives with a low androgenic progestin and spironolactone (100–200 mg/d PO), often in combination. Flutamide is also effective as an antiandrogen, but its use is limited by hepatotoxicity. Glucocorticoids (dexamethasone, 0.25–0.5 mg at bedtime, or prednisone, 5–10 mg at bedtime) are the mainstay of treatment in pts with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Attenuation of hair growth with pharmacologic therapy is typically not evident until 6 months after initiation of medical treatment and therefore should be used in conjunction with nonpharmacologic treatments.

Menopause is defined as the final episode of menstrual bleeding and occurs at a median age of 51 years. It is the consequence of depletion of ovarian follicles or of oophorectomy. The onset of perimenopause, when fertility wanes and menstrual irregularity increases, precedes the final menses by 2–8 years.

The most common menopausal symptoms are vasomotor instability (hot flashes and night sweats), mood changes (nervousness, anxiety, irritability, and depression), insomnia, and atrophy of the urogenital epithelium and skin. FSH levels are elevated to ≥40 IU/L with estradiol levels that are <30 pg/mL.

TREATMENT Menopause

During perimenopause, low-dose combined oral contraceptives may be of benefit. The rational use of postmenopausal hormone therapy requires balancing the potential benefits and risks. Concerns include increased risks of endometrial cancer, breast cancer, thromboembolic disease, and gallbladder disease, as well as probably increased risks of stroke, cardiovascular events, and ovarian cancer. Benefits include a delay in postmenopausal bone loss and probably decreased risks of colorectal cancer and diabetes mellitus. Short-term therapy (<5 years) may be beneficial in controlling intolerable symptoms of menopause, as long as no contraindications exist. These include unexplained vaginal bleeding, active liver disease, venous thromboembolism, history of endometrial cancer (except stage I without deep invasion), breast cancer, preexisting cardiovascular disease, and diabetes. Hypertriglyceridemia (>400 mg/dL) and active gallbladder disease are relative contraindications. Alternative therapies for symptoms include venlafaxine, fluoxetine, paroxetine, gabapentin, clonidine, vitamin E, or soy-based products. Vaginal estradiol tablets may be used for genitourinary symptoms. Long-term therapy (≥5 years) should be undertaken only after careful consideration, particularly in light of alternative therapies for osteoporosis (bisphosphonates, raloxifene) and of the risks of venous thromboembolism and breast cancer. Estrogens should be given in the minimal effective doses (conjugated estrogen, 0.625 mg/d PO; micronized estradiol, 1.0 mg/d PO; or transdermal estradiol, 0.05–1.0 mg once or twice a week). Women with an intact uterus should be given estrogen in combination with a progestin (medroxyprogesterone either cyclically, 5–10 mg/d PO for days 15–25 each month, or continuously, 2.5 mg/d PO) to avoid the increased risk of endometrial carcinoma seen with unopposed estrogen use.

The most widely used methods for fertility control include (1) barrier methods, (2) oral contraceptives, (3) intrauterine devices, (4) long-acting progestins, (5) sterilization, and (6) abortion.

Oral contraceptive agents are widely used for both prevention of pregnancy and control of dysmenorrhea and anovulatory bleeding. Combination oral contraceptive agents contain synthetic estrogen (ethinyl estradiol or mestranol) and synthetic progestins. Some progestins possess an inherent androgenic action. Low-dose norgestimate and third-generation progestins (desogestrel, gestodene, drospirenone) have a less androgenic profile; levonorgestrel appears to be the most androgenic of the progestins and should be avoided in pts with hyperandrogenic symptoms. The three major formulation types include fixed-dose estrogen-progestin, phasic estrogenprogestin, and progestin only.

Despite overall safety, oral contraceptive users are at risk for venous thromboembolism, hypertension, and cholelithiasis. Risks for myocardial infarction and stroke are increased with smoking and aging. Side effects, including breakthrough bleeding, amenorrhea, breast tenderness, and weight gain, are often responsive to a change in formulation.

Absolute contraindications to the use of oral contraceptives include previous thromboembolic disorders, cerebrovascular or coronary artery disease, carcinoma of the breasts or other estrogen-dependent neoplasia, liver disease, hypertriglyceridemia, heavy smoking with age over 35, undiagnosed uterine bleeding, or known or suspected pregnancy. Relative contraindications include hypertension and anticonvulsant drug therapy.

New methods include a weekly contraceptive patch, a monthly contraceptive injection, and a monthly vaginal ring. Long-term progestins may be administered in the form of Depo-Provera or a subdermal progestin implant.

Emergency contraceptive pills, containing progestin only or estrogen and progestin, can be used within 72 h of unprotected intercourse for prevention of pregnancy. Both Plan B and Preven are emergency contraceptive kits specifically designed for postcoital contraception. In addition, certain oral contraceptive pills may be dosed within 72 h for emergency contraception (Ovral, 2 tabs, 12 h apart; Lo/Ovral, 4 tabs, 12 h apart). Side effects include nausea, vomiting, and breast soreness. Mifepristone (RU486) also may be used, with fewer side effects.

Infertility is defined as the inability to conceive after 12 months of unprotected sexual intercourse. The causes of infertility are outlined in Fig. 186-3. Male infertility is discussed in Chap. 185.

FIGURE 186-3 Causes of infertility. FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone.

The initial evaluation includes discussion of the appropriate timing of intercourse, semen analysis in the male, confirmation of ovulation in the female, and, in the majority of situations, documentation of tubal patency in the female. Abnormalities in menstrual function constitute the most common cause of female infertility (Fig. 186-1). A history of regular, cyclic, predictable, spontaneous menses usually indicates ovulatory cycles, which may be confirmed by urinary ovulation predictor kits, basal body temperature graphs, or plasma progesterone measurements during the luteal phase of the cycle. An FSH level <10 IU/mL on day 3 of the cycle predicts adequate ovarian oocyte reserve. Tubal disease can be evaluated by obtaining a hysterosalpingogram or by diagnostic laparoscopy. Endometriosis may be suggested by history and exam, but is often clinically silent and can only be excluded definitively by laparoscopy.

The treatment of infertility should be tailored to the problems unique to each couple. Treatment options include expectant management, clomiphene citrate with or without intrauterine insemination (IUI), gonadotropins with or without IUI, and in vitro fertilization (IVF). In specific situations, surgery, pulsatile GnRH therapy, intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), or assisted reproductive technologies with donor egg or sperm may be required.

For a more detailed discussion, see Ehrmann DA: Hirsutism and Virilization, Chap. 49, p. 380; Hall JE: Menstrual Disorders and Pelvic Pain, Chap. 50, p. 384; Hall JE: The Female Reproductive System: Infertility and Contraception, Chap. 347, p. 3028; and Manson JE, Bassuk SS: The Menopause Transition and Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy, Chap. 348, p. 3040, in HPIM-18.