CHAPTER 193

Seizures and Epilepsy

A seizure is a paroxysmal event due to abnormal excessive or synchronous neuronal activity in the brain. Epilepsy is diagnosed when there are recurrent seizures due to a chronic, underlying process.

APPROACH TO THE PATIENT Seizure

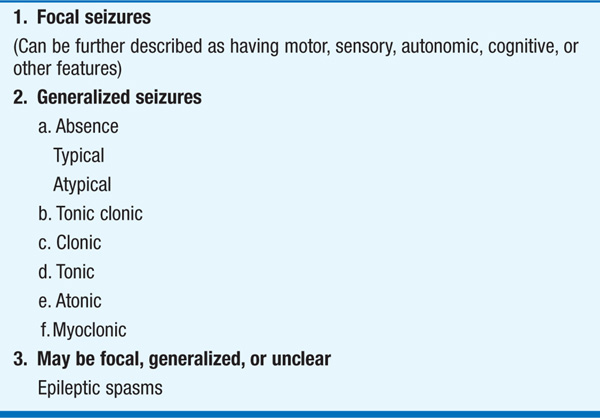

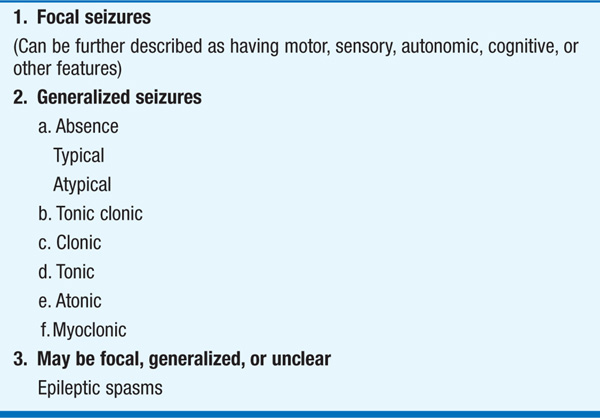

Seizure classification: This is essential for diagnosis, therapy, and prognosis (Table 193-1). Seizures are focal or generalized: focal seizures originate in networks limited to one cerebral hemisphere, and generalized seizures involve networks distributed across both hemispheres. Focal seizures can be described as with or without dyscognitive features depending on the presence of cognitive impairment.

TABLE 193-1 CLASSIFICATION OF SEIZURES

Generalized seizures may occur as a primary disorder or result from secondary generalization of a focal seizure. Tonic-clonic seizures (grand mal) cause sudden loss of consciousness, loss of postural control, and tonic muscular contraction producing teeth-clenching and rigidity in extension (tonic phase), followed by rhythmic muscular jerking (clonic phase). Tongue-biting and incontinence may occur during the seizure. Recovery of consciousness is typically gradual over many minutes to hours. Headache and confusion are common postictal phenomena. In absence seizures (petit mal) there is sudden, brief impairment of consciousness without loss of postural control. Events rarely last longer than 5–10 s but can recur many times per day. Minor motor symptoms are common, while complex automatisms and clonic activity are not. Other types of generalized seizures include tonic, atonic, and myoclonic seizures.

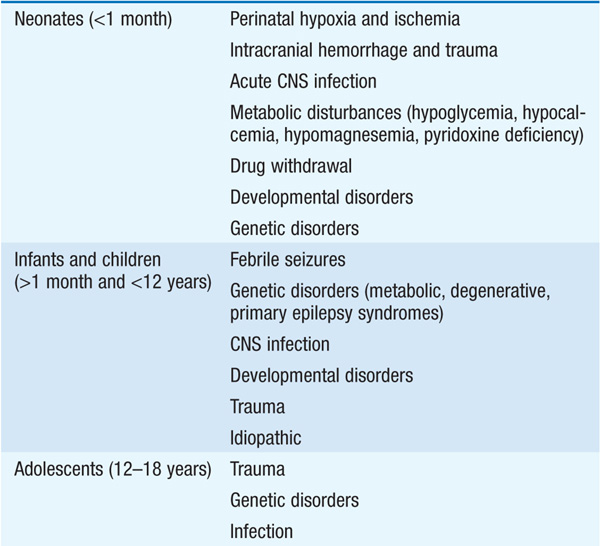

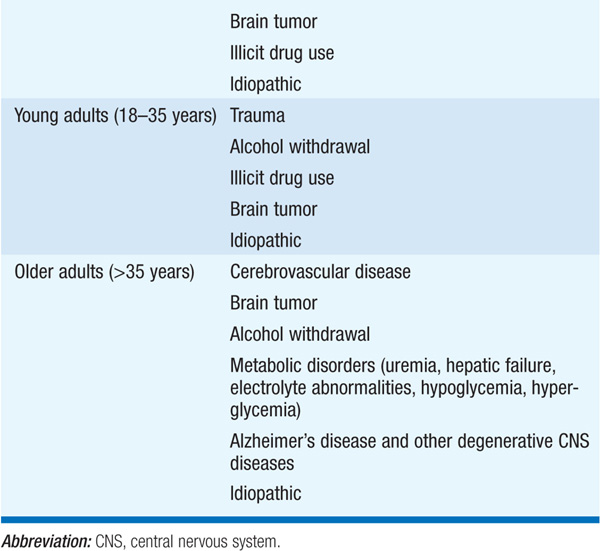

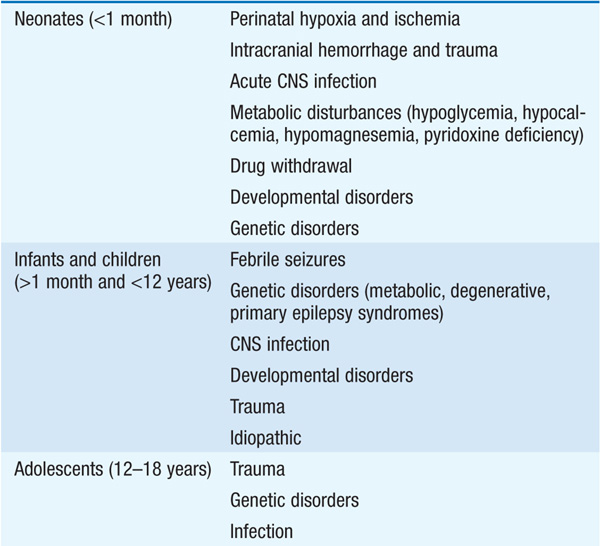

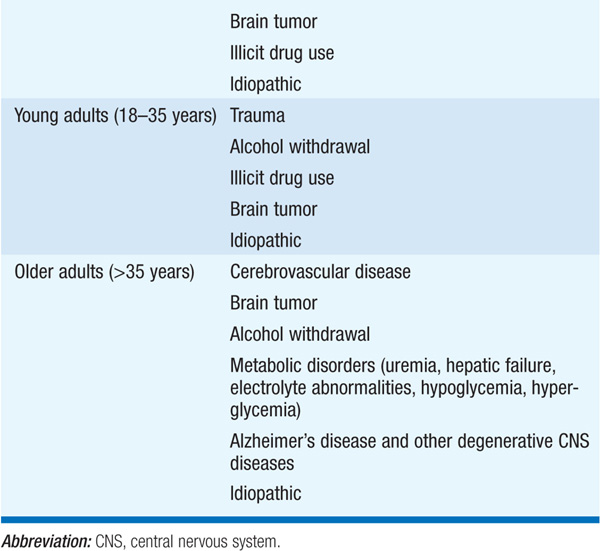

Etiology: Seizure type and age of pt provide important clues to etiology (Table 193-2).

TABLE 193-2 CAUSES OF SEIZURES

CLINICAL EVALUATION

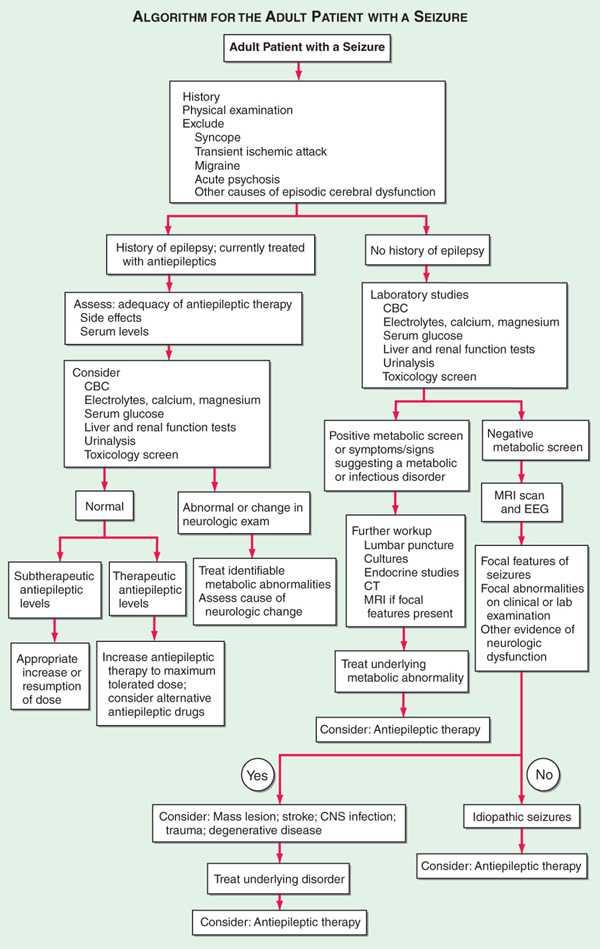

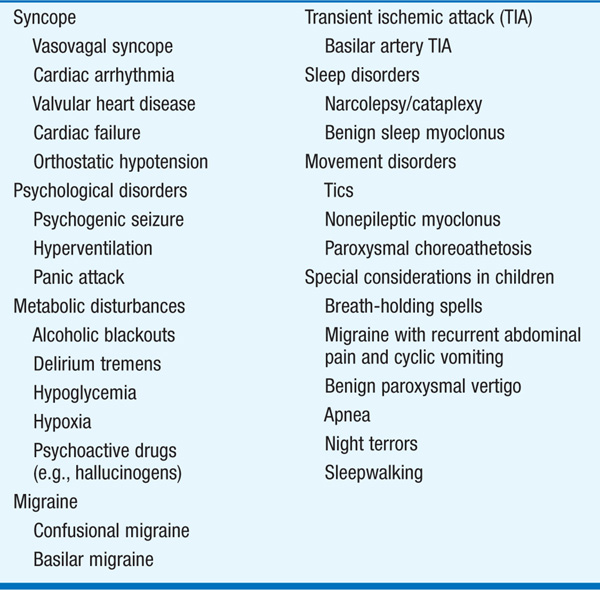

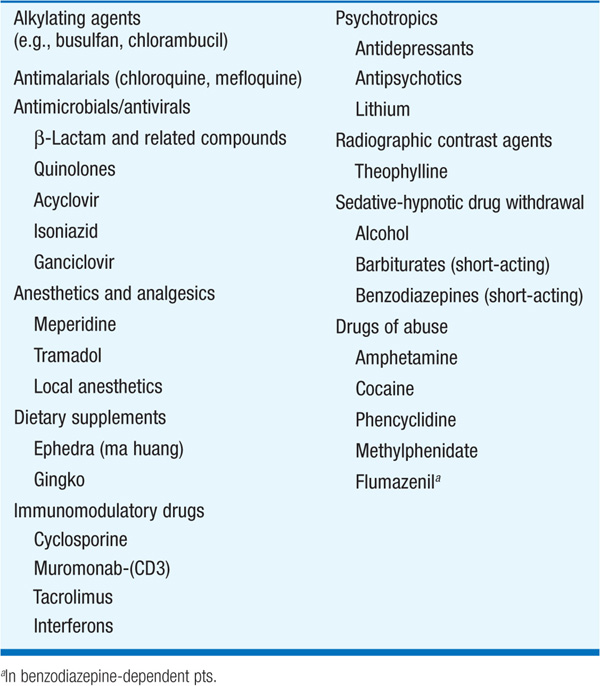

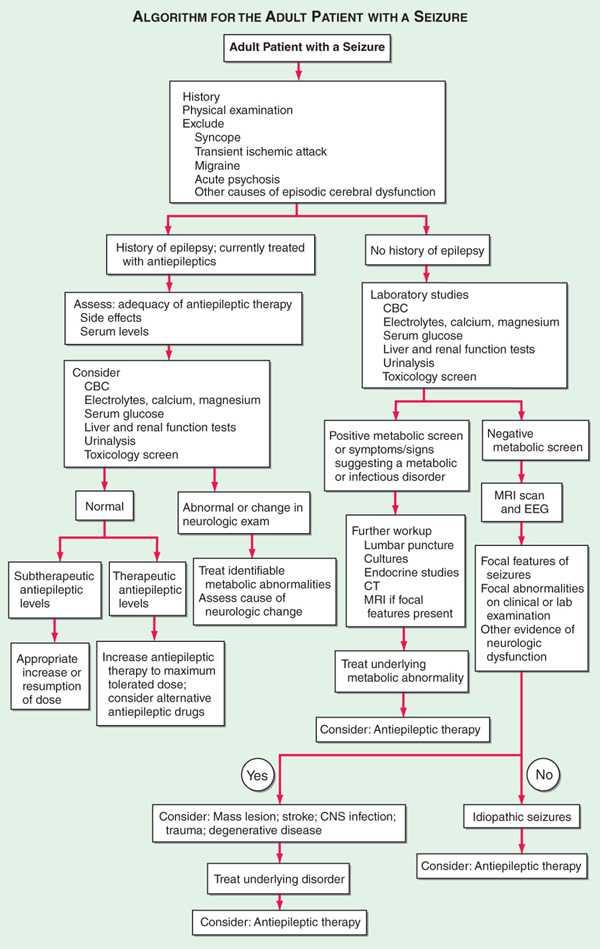

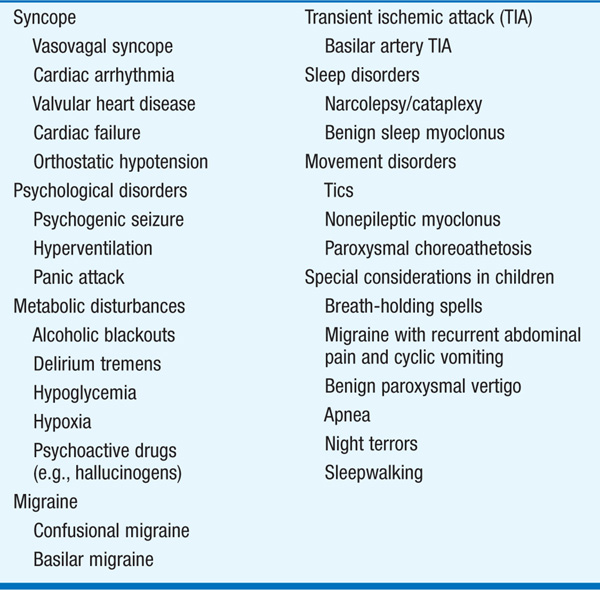

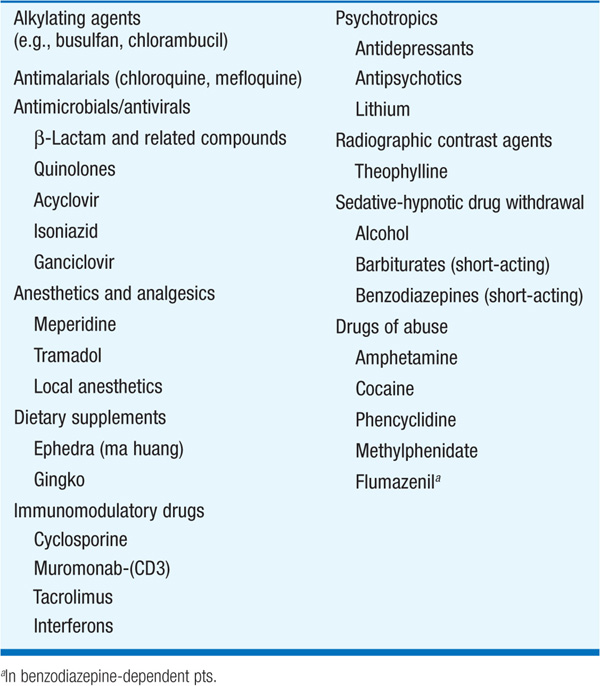

Careful history is essential since diagnosis of seizures and epilepsy is often based solely on clinical grounds. Differential diagnosis (Table 193-3) includes syncope or psychogenic seizures (“pseudoseizures”). General exam includes search for infection, trauma, toxins, systemic illness, neurocutaneous abnormalities, and vascular disease. A number of drugs lower the seizure threshold (Table 193-4). Asymmetries in neurologic exam suggest brain tumor, stroke, trauma, or other focal lesions. An algorithmic approach is shown in Fig. 193-1.

FIGURE 193-1 Evaluation of the adult pt with a seizure. CBC, complete blood count; CNS, central nervous system; CT, computed tomography; EEG, electroencephalogram; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

TABLE 193-3 DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF SEIZURES

TABLE 193-4 DRUGS AND OTHER SUBSTANCES THAT CAN CAUSE SEIZURES

LABORATORY EVALUATION

Routine blood studies are indicated to identify the more common metabolic causes of seizures such as abnormalities in electrolytes, glucose, calcium, or magnesium, and hepatic or renal disease. A screen for toxins in blood and urine should be obtained especially when no clear precipitating factor has been identified. A lumbar puncture is indicated if there is any suspicion of CNS infection such as meningitis or encephalitis; it is mandatory in HIV-infected pts even in the absence of symptoms or signs suggesting infection.

Electroencephalography (EEG)

All pts should be evaluated as soon as possible with an EEG, which measures electrical activity of the brain by recording from electrodes placed on the scalp. The presence of electrographic seizure activity during the clinically evident event, i.e., abnormal, repetitive, rhythmic activity having an abrupt onset and termination, clearly establishes the diagnosis. The absence of electrographic seizure activity does not exclude a seizure disorder, however. The EEG is always abnormal during generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Continuous monitoring for prolonged periods may be required to capture the EEG abnormalities. The EEG can show abnormal discharges during the interictal period that support the diagnosis of epilepsy and is useful for classifying seizure disorders, selecting anticonvulsant medications, and determining prognosis.

Brain Imaging

All pts with unexplained new-onset seizures should have a brain imaging study (MRI or CT) to search for an underlying structural abnormality; the only exception may be children who have an unambiguous history and examination suggestive of a benign, generalized seizure disorder such as absence epilepsy. Newer MRI methods have increased the sensitivity for detection of abnormalities of cortical architecture, including hippocampal atrophy associated with mesial temporal sclerosis, and abnormalities of cortical neuronal migration.

TREATMENT Seizures and Epilepsy

• Acute management of seizures

– Pt should be placed in semiprone position with head to the side to avoid aspiration.

– Tongue blades or other objects should not be forced between clenched teeth.

– Oxygen should be given via face mask.

– Reversible metabolic disorders (e.g., hypoglycemia, hyponatremia, hypocalcemia, drug or alcohol withdrawal) should be promptly corrected.

– Treatment of status epilepticus is discussed in Chap. 23.

• Longer-term therapy includes treatment of underlying conditions, avoidance of precipitating factors, prophylactic therapy with anti-epileptic medications or surgery, and addressing various psychological and social issues.

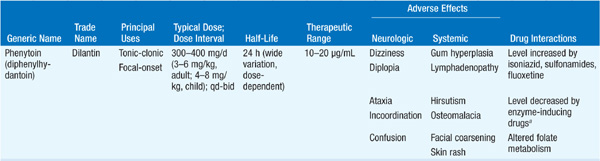

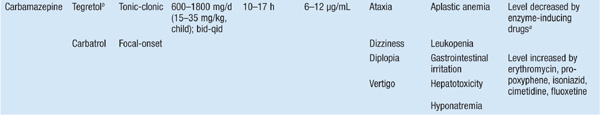

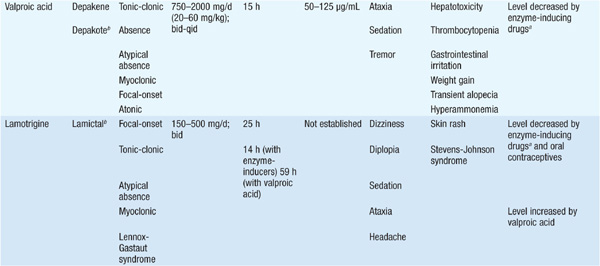

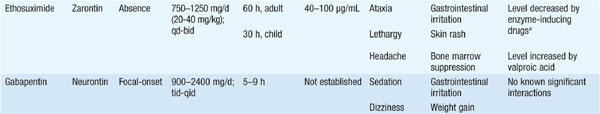

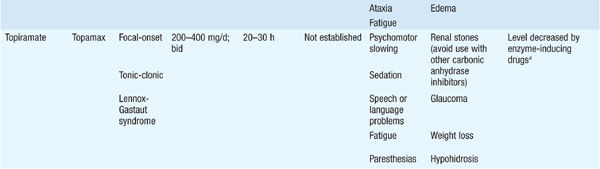

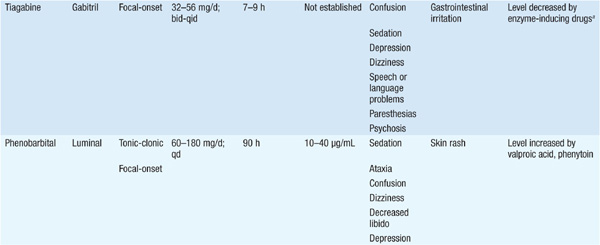

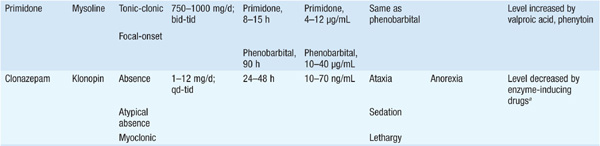

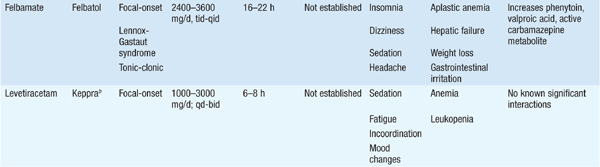

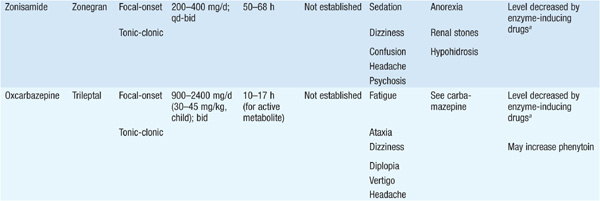

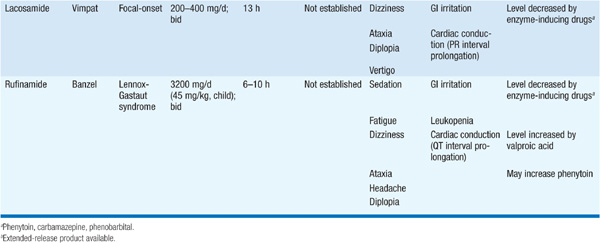

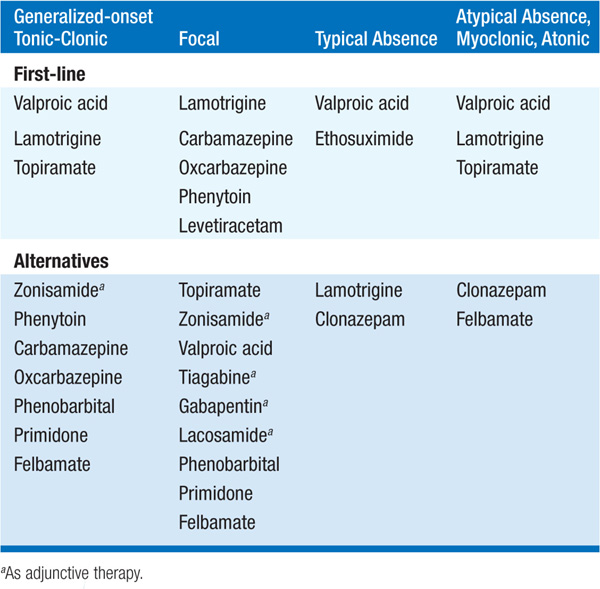

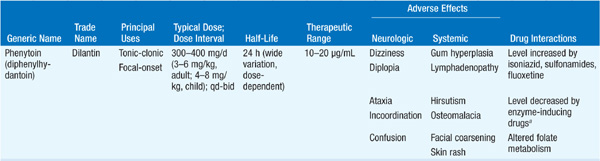

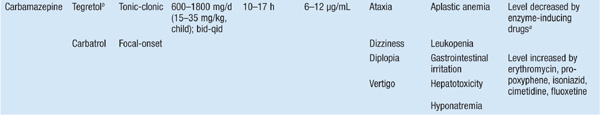

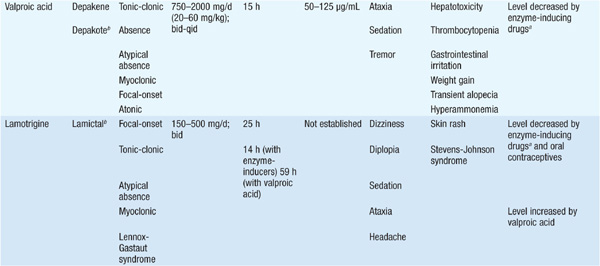

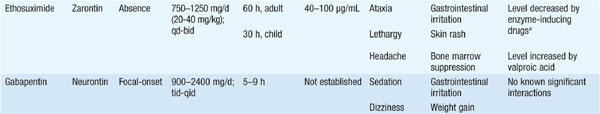

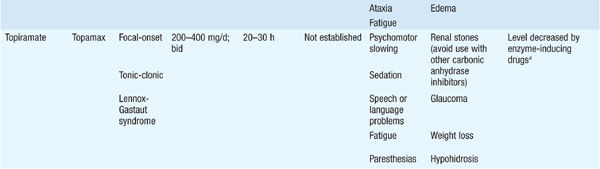

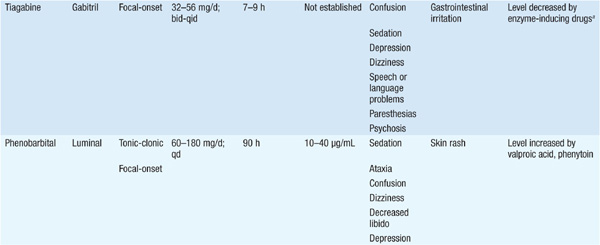

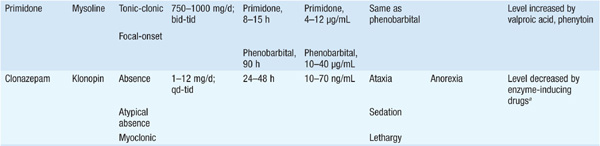

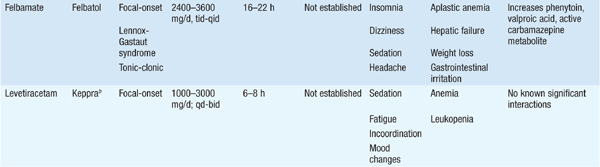

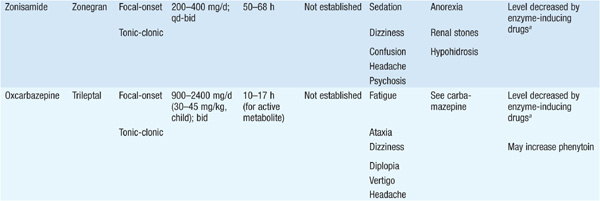

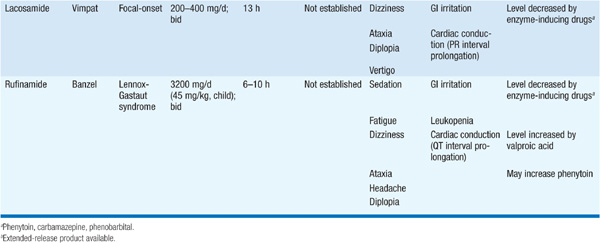

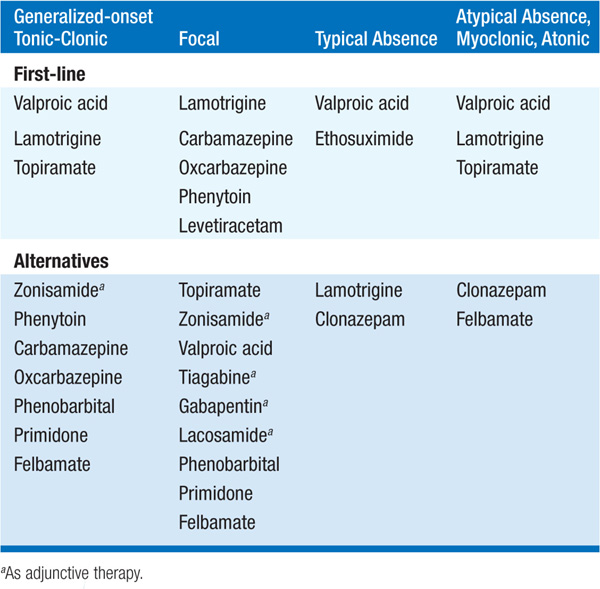

• Choice of antiepileptic drug therapy depends on a variety of factors including seizure type, dosing schedule, and potential side effects (Tables 193-5 and 193-6).

TABLE 193-5 DOSAGE AND ADVERSE EFFECTS OF COMMONLY USED ANTIEPILEPTIC DRUGS

TABLE 193-6 SELECTION OF ANTIEPILEPTIC DRUGS

• Therapeutic goal is complete cessation of seizures without side effects using a single drug (monotherapy) and a dosing schedule that is easy for the pt to follow.

– If ineffective, medication should be increased to maximal tolerated dose based primarily on clinical response rather than serum levels.

– If still unsuccessful, a second drug should be added, and when control is obtained, the first drug can be slowly tapered. Some pts will require polytherapy with two or more drugs, although mono-therapy should be the goal.

– Pts with certain epilepsy syndromes (e.g., temporal lobe epilepsy) are often refractory to medical therapy and benefit from surgical excision of the seizure focus.

For a more detailed discussion, see Lowenstein DH: Seizures and Epilepsy, Chap. 369, p. 3251, in HPIM-18.