In the chill air of early-morning markets in the Mekong Delta and Cambodia, we’re always seduced by the wonderful scent of jasmine rice. Most often it’s simple plain rice, cooked in a steamer or rice cooker or a big heavy pot. But it may instead be rice bubbling gently in a rice soup, known in Cambodia as babah (see Rice Soup, Khmer Style, page 94) and in Vietnam as chao (see Shrimp and Rice Soup, page 95).

In Laos and northeast and northern Thailand, we’re more likely to see or to sniff out sticky rice steaming over boiling water in a tall conical basket, shiny and aromatic long-grain sticky rice, the staple food in all three regions. Farther north again, in the Shan areas and beyond to southern Yunnan, rice most often means plain aromatic long-grain rice, eaten two or three times a day.

“Gin khao?” asks one Thai friend to another when they meet. “Have you eaten?” But the phrase literally means “Have you eaten rice?”

Rice is at the heart of most Southeast Asian meals, eaten plain, the essential food that anchors life. The rest of the meal may be made up of many dishes or may consist only of a dipping sauce or a salsa or a plate of vegetables to accompany the rice. Aromatic jasmine rice is quick to prepare, so if the pot runs low, more can be cooked up at any time; whatever else may be on the table, it’s important never to run out of rice.

Rice cooked with other flavorings makes another whole category of food in the region, from Lao Yellow Rice and Duck (page 102) in Laos to the seductive Vietnamese Sticky Rice Breakfast (page 98) of southern Vietnam, sticky rice with herbs and coconut milk.

Dishes made with leftover rice are some of our favorite foods: Jasmine rice can be quickly stir-fried with garlic and a little meat, or in a flavor paste, then eaten with a sprinkling of coriander leaves and a squeeze of lime juice (see Thai Fried Rice, page 110, and Perfume River Rice, page 111). It can also be shaped into balls and deep-fried (see Deep-fried Jasmine Rice Balls, page 104) or dried and then deep-fried to make delicious crackers (see Thai-Lao Crispy Rice Crackers, page 106).

The agricultural cycle in Southeast Asia alternates with the season. Rice harvest in northern Thailand is November to January, after the end of the rainy season. The rice is cut, leaving fields of golden stubble (near Chiang Mai).

In winter, it’s time to plant shallots (near Hot in northern, Thailand).

Jasmine rice is aromatic as it cooks, filling the house with its scent and a promise of good food to come. It is our favorite daily rice, soft and slightly clingy when cooked. We buy it in twenty-pound bags, usually labeled “Thai Jasmine” or “Thai Fragrant Rice” and also marked “superior quality” or “milagrosa.” Perhaps sometime soon we’ll also be seeing high-quality Cambodian and Vietnamese jasmine rice in the markets.

You can also substitute American-grown fragrant rice for Thai jasmine. The best-tasting jasmine rice from the United States we’ve found is produced by Lowell Farms in Texas. It’s organically grown and carefully milled. It needs a little more cooking water than Thai jasmine and a few more minutes’ cooking time (20 minutes at a simmer instead of 15).

Jasmine rice should be thoroughly washed in cold water, then cooked plain, with no salt and no oil. When cooked, it has an aromatic flavor and a good straightforward taste of grain. The dishes served with the rice supply all the seasoning needed.

3 cups long-grain Thai jasmine rice

Wash the rice thoroughly: Place it in a large wide heavy pot (3½-quart capacity or more) with a tight-fitting lid. Add cold water, swirl around several times with your hand, and drain; repeat twice more, or until the water runs clear. Add the cooking water: We add water measured the traditional way, that is, enough to cover the rice by about ½ inch, measured by placing the tip of the index finger on the surface of the rice and adding enough so that the water comes to the first joint. If you prefer to use more exact measured amounts, drain the washed rice well in a sieve, return to the pot, and add 3¾ cups cold water.

Bring the water to a full boil, uncovered, and let boil for about 15 seconds. Cover tightly, lower the heat to the lowest setting possible, and cook, without lifting the lid, for 15 minutes. Remove from the heat and let stand, covered, for 5 to 10 minutes. When you take off the lid, you will see the grains of rice standing up firmly on the top layer. Turn the rice gently with a rice paddle or wooden spoon, then place the lid back on to keep it warm. It’s best served within 1 hour of cooking.

Store leftover rice in a sealed container in the refrigerator for up to three days. You can take it straight from there to make fried rice (see Index) or to add to hot broth.

MAKES about 7 cups rice; serves 4 to 6

NOTE: TO USE A RICE COOKER: Rice cookers usually come with instructions listing the volume of water to use for a given amount of rice. The rice should be well washed as above, then cooked according to the rice cooker directions. If there are no water:rice proportions marked on your rice cooker, use just a touch less water than in the method above. If using a measured amount of water, drain the washed rice well in a colander before placing in the rice cooker and adding the water.

If there is any one food that for us symbolizes the regional cuisines of Southeast Asia, it is sticky rice. It is the staple food, the staff of life, in Laos, northern Thailand, and northeast Thailand. It is also widely eaten in Cambodia, Vietnam, Yunnan, and other parts of Thailand, and it is often used for making sweets and ceremonial foods.

Sticky rice is medium to long grain and opaque white before cooking. It is a different variety of rice from jasmine, “sticky” when cooked because it contains a different form of starch (it is very low in amylose and is high in amylopectin). It is sometimes called sweet rice or glutinous rice. Sticky rice from Thailand is often sold marked pin kao, or with the Vietnamese term for sticky rice, gao nep.

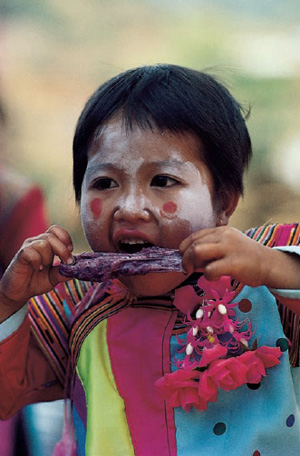

Sticky rice is fun, liberating food. No utensils are needed. When it comes to eating sticky rice for the first time, children are usually better than adults; they have no problem eating with their fingers. For us, sticky rice is a way of eating, a way of organizing meals. To eat it, take a large ball of rice in one hand, then pull a smaller bite-sized piece off with your other hand and squeeze it gently into a firm clump. Then it’s almost like a piece of bread: Use it to scoop up some salsa or a piece of grilled chicken.

To prepare sticky rice, you must first soak it overnight in cold water. It is then steam-cooked in a basket or steamer over a pot of boiling water. The long soaking gives the rice more flavor, but you can take a short-cut and soak it in warm water for just 2 hours.

People tend to eat a lot of sticky rice, or at least we do, and so do our friends, so we cook 3 cups for 4 to 6 hungry adults.

3 cups long-grain Thai sticky rice

EQUIPMENT NOTE: You will need a large pot for soaking the rice and a rice-steaming arrangement; there are several different options for steaming sticky rice. By far the best is the traditional basket and pot. If you can shop in a Thai, Lao, or Vietnamese grocery, chances are you can buy the conical basket used for cooking sticky rice as well as the lightweight pot the basket rests in as it steams. You can also buy the basket and pot by mail-order (see Sources, page 325). This is the ideal equipment for cooking sticky rice—low-cost and made for the purpose. However, you can improvise by using a Chinese bamboo steamer or a steamer insert, or a large sieve. Line it with cheesecloth or muslin, place over a large pot of water, and cover tightly. The steamer must fit tightly so that no steam escapes around the edge and all the steam is forced up through the rice.

Soak the rice in a container that holds at least twice the volume of the rice: Cover the rice with 2 to 3 inches of room-temperature water and soak for 6 to 24 hours. If you need to shorten the soaking time, soak the rice in warm (about 100°F) water for 2 hours. The longer soak gives more flavor and a more even, tender texture, but the rice is perfectly edible with the shorter soak in warm water.

Drain the rice and place in a conical steamer basket or alternative steaming arrangement (see Equipment Note). Set the steamer basket or steamer over several inches of boiling water in a large pot or a wok. The rice must not be in or touching the boiling water. Cover and steam for 25 minutes, or until the rice is shiny and tender. If using an alternative steaming arrangement, turn the rice over after about 20 minutes, so the top layer is on the bottom. Be careful that your pot doesn’t run dry during steaming; add more water if necessary, making sure to keep it from touching the rice.

Turn the cooked rice out onto a clean work surface. Use a long-handled wooden spoon to flatten it out a little, then turn it over on itself, first from one side, then from the other, a little like folding over dough as you knead. This helps get rid of any clumps; after several foldings, the rice will be an even round lump. Place it in a covered basket or in a serving bowl covered by a damp cloth or a lid. Serve warm or at room temperature, directly from the basket or bowl. The rice will dry out if exposed to the air for long as it cools, so keep covered until serving. In Thailand and Laos, cooked sticky rice is kept warm and moist in covered baskets.

MAKES about 6½ cups rice; serves 4 to 6

Border towns are always seedy—sometimes more, sometimes less, but always seedy. Maybe it’s because there are different rules (and different opportunities) on either side of the border, so inherently there is a bit of flimflam, zigzag, riffraff, whatever.

Mae Sai, a northern Thai town at the junction of Burma, Laos, and Thailand (the Golden Triangle), is no exception. Its one long commercial street, which leads directly to the bridge that crosses to Burma, looks like a frontier version of a strip mall that never ends. People come across from Burma every day, all day, shopping and selling up and down the long street, every once in a while stopping to eat. If you find a comfortable seat and watch long enough, you will see Shan, Akha, Burmese, Lahu, Kachin, and Kalaw, but you could watch a lifetime and not know exactly who everyone was and what they were up to, not really.

We didn’t expect to spend much time in Mae Sai. We’d been there several times before and had never found it very appealing. Also, it’s not a perfect family spot. We’d come only to see if it was possible to go by road to Kengtung, an important old town in the Shan hills in Burma. Someone had told us to go to Chad’s Guest House, that Chad could help us (because it would have to be a less-than-official trip to Burma).

But Chad immediately said no. It had been possible for a time, but now, no. Maybe someone else could help us, but not him. So anyway, there we were, at Chad’s, and so we stayed for the night. That night we got to talking with Chad’s mother and sister, and with his niece Shieng, and discovered that they were Tai Koen and Shan, and, sure, they would be happy to teach us about Tai Koen and Shan cooking (which was a big reason why we’d wanted to go to Kengtung). And meanwhile, Chad was working hard fixing up his vintage World War II jeeps, his true passion, and he didn’t mind Dom and Tashi playing on the jeeps, or sitting on his antique motorbikes, so we decided we quite liked Mae Sai after all.

We stayed a while, hanging out in the kitchen and at the markets. We spent a lot of time at the markets, the morning market, the evening market, and the all-day cross-border everything-but-the-kitchen-sink market. The food markets in Mae Sai are incredible: There are Shan and Tai Koen specialties such as deep-fried donuts made of black sticky rice, flattened cakes of dried soybean used to flavor local dishes, tangled green piles of Mekong river weed (see River Weed, page 165), and khao foon, a dense yellowish jelly made of soured rice and eaten for breakfast with chiles, garlic, and black vinegar (see Khao Foon, page 108).

At night, after dinner, if we could get Chad talking, we’d hear wonderful tales of mystery and intrigue. Chad’s parents once ran a small restaurant in town. For years Khun Sa, a famous drug warlord, would come once a week to play bridge with his mother, and Chad would watch and listen. But like all good storytellers, Chad would leave us hanging, leave us sitting on the edge of our chairs, when he decided it was time to start working again on his jeeps.

Tobacco is an important cash crop in northern, Thailand along the Burmese border and is harvested and dried in the winter months.

All over Southeast Asia, there are versions of this one-dish meal, a thick soup of rice cooked in plenty of water or broth, then flavored with toppings and condiments. In Cantonese it’s known as juk, in Thai as khao tom, in Vietnam it’s chao (see page 95), and in Cambodia it’s known as babah. I had my first bowl of babah as a snack on my way in from the airport and my last, in hurried regret, just before leaving Phnom Penh.

This is comfort food at any hour in any season, quickly prepared and very easy and satisfying. Make it on a chilly evening, or for lunch when you want your guests to feel taken care of. The whole dish can be made in just over half an hour, yet it tastes of slow simmering.

¼ pound ground pork

1 tablespoon Thai fish sauce

1 teaspoon sugar

6 cups water

2 stalks lemongrass, trimmed and smashed flat with the side of a cleaver

1 tablespoon dried shrimp

1-inch piece ginger, peeled and smashed flat

¾ cup Thai jasmine rice, rinsed well in cold water

2 tablespoons peanut or vegetable oil

5 cloves garlic

GARNISH AND ACCOMPANIMENTS

¼ cup Thai fish sauce

1 bird chile, chopped

2 tablespoons peanut or vegetable oil

2 shallots, chopped

4 leaves sawtooth herb, 6 sprigs rice paddy herb (ngo om), and/or about 12 leaves Asian basil, coarsely torn

2 cups bean sprouts, thoroughly rinsed in very hot water

2 scallions, trimmed and minced

Freshly ground black or white pepper

¼ cup Dry-Roasted Peanuts (page 308), coarsely chopped

1 lime, cut into wedges (optional)

In a small bowl, combine the pork with the fish sauce and sugar, mix well to blend, and set aside.

Place the water in a large heavy pot over high heat, add the lemongrass, dried shrimp, and ginger, and bring to a boil. Boil vigorously for 5 to 10 minutes, then sprinkle in the rice and stir gently with a wooden spoon until the water returns to a boil. Maintain a steady gentle boil until the rice is tender, 15 to 20 minutes, then turn off the heat. Remove and discard the lemongrass and ginger if you wish.

In the meantime, in a wok or heavy skillet, heat the oil. Add the garlic and stir-fry for 30 seconds, or until it is starting to turn golden. Toss in the pork and stir-fry, using your spatula to break up any lumps, until all the pork has changed color, about 2 minutes. Transfer the contents of the skillet to the soup and stir in.

Combine the fish sauce and chile in a condiment bowl; set aside.

Heat the oil in a small heavy skillet or in a wok over medium-high heat. Toss in the shallots and cook, stirring constantly, until golden, 2 to 3 minutes. Turn the shallots and oil out into a small bowl and set aside.

Just before serving, reheat the soup, stirring to prevent it from sticking. Divide the herbs you are using among four large soup bowls. Top the herbs in each bowl with ½ cup bean sprouts and a pinch of scallions. Pour the soup over top, then top each with another pinch of scallions, some shallots and oil, a very generous grinding of pepper, and a scattering of chopped peanuts. Serve with the fish sauce and chiles and lime wedges if you wish.

SERVES 4 as a one-dish meal

SHRIMP AND RICE SOUP

From China to Thailand, rice soup makes a great breakfast or between-meals snack or late-night supper. This quickly prepared Vietnamese rice soup has small pieces of shrimp cooked in a lightly flavored broth loaded with tender rice. A garnish of chopped roasted peanuts adds a pleasant change of texture and a nutty taste. The soup is traditionally served with a side dish of Vietnamese Must-Have Table Sauce so guests can add extra flavoring as they wish.

2 shallots, coarsely chopped

4 large cloves garlic, 2 minced and 2 peeled but left whole

½ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper or ¼ teaspoon freshly ground white pepper

2 tablespoons Vietnamese or Thai fish sauce

½ pound peeled and deveined shrimp (about ¾ pound in the shell), coarsely chopped

2 quarts water (or half pork or chicken broth, half water)

1 cup Thai jasmine rice, rinsed well in cold water

2 stalks lemongrass, trimmed and minced

2 tablespoons peanut or vegetable oil

2 medium tomatoes, coarsely chopped (optional)

GARNISH AND ACCOMPANIMENTS

2 to 3 tablespoons Dry-Roasted Peanuts (page 308), coarsely chopped

1 cup loosely packed coriander leaves

½ cup Vietnamese Must-Have Table Sauce (nuoc cham, page 28)

1 to 2 bird or serrano chiles, minced

Place the shallots, 1 whole garlic clove, and the pepper in a mortar and pound to a paste. Stir in 1 tablespoon of the fish sauce, then add the shrimp and pound together. Alternatively, mince the shallots and garlic clove, transfer to a bowl, and add the pepper and 1 tablespoon fish sauce. Finely chop the shrimp, add to the mixture, and turn to coat. Set aside.

Place the water (or stock and water) in a large pot. Add the rice and bring to a boil.

Meanwhile, pound the remaining whole garlic clove with the lemongrass in a mortar, or grind in a blender. Add to the rice water. Once the rice is boiling, lower the heat to medium and simmer, half covered, for about 15 minutes, or until the rice is very tender.

While the rice simmers, heat the oil in a skillet or wok over high heat. When it is hot, add the minced garlic and stir-fry for 30 seconds, or until golden, then add the shrimp with the marinade and stir-fry until the shrimp starts to change color, about 1 minute.

Add the fried shrimp mixture to the rice and toss in the tomatoes, if using. Scoop out about ½ cup of liquid from the soup to rinse out the skillet or wok and pour back into the soup. Continue simmering the soup for another 5 minutes, then serve. Or remove from the heat and let stand until just before you wish to serve (refrigerate if letting stand for more than 1 hour); reheat before serving.

Sprinkle a few roasted peanuts and some coriander leaves over each bowl of soup, then serve with side dishes of the remaining peanuts and coriander, the table sauce, and the minced chiles, so guests can adjust flavorings as they wish.

SERVES 6

There are many grades of rice to choose from in even the smallest market in the region; here, at the main market in Vientiane, the choice is particularly wide.

In northern Thailand, after the rice is harvested, the rice straw is often piled into stacks around a tidy conical pole.

Early-morning street vendors, steam rising from their pots of soup or their baskets of rice, are a welcome sight for the hungry early riser. Out taking photographs at dawn in Chau Doc, a Vietnamese town on the Mekong River right by the Cambodian border, I saw a small crowd of people hanging around an old woman vendor. She was selling xoi, sticky rice cooked with beans, in this case split mung beans. Unlike the northern Vietnamese version, in which the rice is cooked plain with some peanuts or whole beans, in the Delta version of xoi, I discovered a world of flavor choices that seemed both wild and wonderful.

The sticky rice steams with mung beans that have cooked in coconut milk. To eat it, you begin with a generous dollop of rice and beans in your bowl, then top them with some or all of the following: coconut cream, dry-roasted peanuts, dry-roasted sesame seeds, sugar, coriander leaves, and chopped scallions. That’s the basic array (see Notes for options). Though these may not be the first toppings you’d think of for sticky rice, the flavorings come together beautifully to give richness, moisture, crunch, and, of course, lots of flavor, to this homey, simple, and nourishing breakfast-time street fare. Serve for breakfast or a snack, to be eaten with a spoon.

The total cooking time is less than 1 hour, and the beans can be cooked ahead, in which case the final cooking time is only the time it takes to steam the rice, about 25 minutes.

½ cup yellow split mung beans, soaked for 8 to 24 hours in cold water

About 1 cup canned or fresh medium to thin coconut milk (see page 315)

2 cups Thai or Vietnamese sticky rice, soaked for 8 to 24 hours in cold water (see Basic Sticky Rice, page 91)

TOPPINGS AND ACCOMPANIMENTS

About 2 tablespoons Dry-Roasted Sesame Seeds (page 308)

½ teaspoon salt

¼ to ¾ cup canned or fresh coconut cream or thick coconut milk

4 to 6 tablespoons Dry-Roasted Peanuts (page 308), coarsely chopped

2 to 3 tablespoons sugar (optional)

About ½ cup coarsely torn coriander leaves (optional)

Greens of 2 scallions, finely chopped (optional)

EQUIPMENT NOTE: The soaked rice is steamed together with the cooked mung beans. You can use a Chinese bamboo steamer, lined with muslin or cheesecloth and placed over a wok or pot of boiling water, or a Lao-Thai sticky rice steaming basket (see Basic Sticky Rice, page 91, for details on steaming sticky rice). We’ve worked with both arrangements and find the rice steaming basket to be quicker and easier.

Drain the mung beans and place in a pot with just enough coconut milk to cover. Bring to a rapid boil, stirring to prevent sticking, then lower the heat and cook at a simmer, half-covered, until the beans are very soft, about 20 minutes, stirring occasionally to prevent sticking or burning; if the beans do begin to stick, add a little more liquid. Remove from the heat and mash with a spoon or potato masher or in a food processor. Spoon the beans into a bowl and pat down firmly, pouring off any excess liquid. (The beans can be made ahead and stored, covered, in the refrigerator, for up to 2 days.)

If using a conical steamer basket, fill the pot with about 2 inches of water, place the basket in the pot, and put the rice in the basket. If using a bamboo steamer, line it with muslin, cheesecloth, or a cotton cloth and place it over a large pot or wok filled with 2 to 3 inches of water (the steamer should not be touching the water); spread the rice out in the cloth-lined steamer. Crumble the cooked mung beans over the rice. Mix the rice gently with your hands to distribute the beans through the top layer of the rice.

Place the pot over high heat and bring the water to a boil. If using a basket, cook for 25 minutes, or until tender, making sure the water doesn’t run dry. If using a bamboo steamer, make sure that the steam is not escaping around the sides of the steamer; it must be forced through the rice. Once you see the steam coming up through the rice, cover the steamer tightly with a lid or aluminum foil and cook for 25 to 30 minutes, until tender. After about 12 minutes, lift the lid and turn the rice and bean mixture over. Using oven mitts to protect your hands from the steam, lift out the steamer and check the level of water in the pot. If it looks very low, add hot water, then place the steamer back over the water, cover, and continue to cook.

While the rice is cooking, briefly pound the roasted sesame seeds in a mortar or grind in a spice grinder and transfer to a small bowl. You can set the condiments out on separate small plates or bowls so guests can help themselves, or serve each guest an already garnished bowl of xoi.

Turn the cooked rice and bean mixture out into a bowl. Sprinkle on the salt and use a wooden spatula or spoon to turn the rice to blend. To assemble an individual serving, place about ¾ cup of the rice and bean mixture in a bowl, then top with 1 to 2 tablespoons thick coconut milk, about 1 teaspoon sesame seeds, 1 tablespoon chopped roasted peanuts, a generous sprinkling of sugar (begin with a heaping teaspoon), and a large pinch of coriander leaves and some minced scallions, if using.

SERVES 4 to 6

NOTES: You can also serve xoi as a flavored rice (without the sugar and coconut cream toppings) to accompany grilled meats or vegetables or roast pork or chicken in a Western-style meal. It makes a great contribution to a potluck supper.

We like to make twice the amount of beans called for, then serve the extra beans as another optional topping for the rice.

In Ho Chi Minh City, we’ve eaten xoi with an even wider selection of toppings, including slices of Vietnamese Baked Cinnamon Pâté (page 259) or sliced cooked sausages. It then becomes a substantial meal, great for brunch or lunch, especially if you have a hungry crowd to feed.

We’re not particularly confident when it comes to handling motorcycles, especially larger ones, roadworthy ones, though we really wish we could be.

If we ever get to feeling comfortable with them, the first place we’ll go is northern Thailand. Occasionally we meet people traveling there on motorbikes, and we’re always jealous. The roads are so windy and deserted. The air is so fresh and clean. And the hills of northern Thailand always have that element of mystery. There are tribal people living in villages hidden in the hills; follow a dirt track, and sooner or later there will be a village. And then there is all the intrigue of the opium trade, though now everyone is growing strawberries instead of poppies. But there is still the intrigue.

We’ve often wondered about all the little roads in Thailand. Thailand has a lot of roads, and they are in pretty good condition. We used to think that the roads had all been built by U.S. drug enforcement money, to bring the poppy-growing tribals more into the fabric of Thai life, giving them access to schools and hospitals, and, in turn, giving the military and the police easier access in policing the poppy cultivation. But then we realized that it’s not just the north, but other parts of the country as well.

“Why so many roads?” A Thai friend at last told us: “The reason we have so many roads is because so many of our politicians come from the construction industry. What is the English term? Kickback?”

Opium poppies bloom in the hills of Laos, Thailand, Vietnam, and Yunnan. During the colonial era, opium became an important cash crop.

LAO YELLOW RICE AND DUCK

This impressive dinner-party dish is easy to make and fun to serve. We learned it from Sivone Penasy, who lives with her husband, Sousath, and their two children, Melissa and Peter, in the “wild west” town of Phonsavan, near the Plain of Jars in eastern Laos (see The War, page 187).

4 cups jasmine rice

One 3½-pound duck

15 cloves garlic, peeled

1 tablespoon black peppercorns

2 teaspoons salt

1 tablespoon Madras curry powder

1 teaspoon ground turmeric (optional)

2 tablespoons Thai fish sauce

5 tablespoons vegetable oil or rendered duck fat

6½ cups water, or more if needed

6 small scallions, trimmed and cut lengthwise into fine ribbons

Place the rice in a bowl, add cold water to cover by 2 inches, and set aside to soak.

Use a cleaver to cut the duck into 12 to 15 pieces. Reserve the wing tips and neck for stock (see Notes). Trim off all the fat and thick skin and reserve for another purpose if desired.

Place the garlic cloves in a mortar with the peppercorns and the salt and pound to a paste. Alternatively, mince the garlic and place in a small bowl with the salt. Grind the peppercorns in a spice grinder and stir into the garlic, mashing with the back of the spoon. Add the curry powder and optional turmeric to the garlic paste and stir to blend, then stir in the fish sauce.

Place a large wide heavy pot over medium-high heat. When it is hot, add 2 tablespoons of the oil or fat and toss in the prepared paste. Cook for about 30 seconds, stirring to prevent sticking or burning, then add the duck pieces. Stir to coat all the duck with the flavored oil, then cook, stirring frequently, until all the pieces are lightly browned, about 10 minutes. (If your pot is narrow, you may have to cook the duck in two batches, using half the paste and oil for each, then return all the duck to the pot.) Add 2 cups of the water, bring to a boil, and simmer gently for 10 minutes.

Add the remaining 4½ cups water to the pot and bring to a boil. Drain the rice. Add the remaining 3 tablespoons vegetable oil or fat to the pot, then sprinkle in the rice; the liquid should cover the rice by a scant ½ inch. Add more water if necessary. Bring back to a boil, then cover tightly, lower the heat to medium-low, and cook until the rice is tender, 15 to 20 minutes. Remove from the heat and let stand 5 to 10 minutes.

Turn the rice and duck out onto a large platter and mound attractively. Garnish with the scallion ribbons and serve hot or at room temperature.

SERVES 8 as the centerpiece of a meal

NOTES: Sivone says she uses the same technique to cook beef or chicken. If using beef, use 2 to 2½ pounds boneless rump or shoulder, cut into rough 1-inch chunks. Add 2 tablespoons minced ginger to the paste, pounding it with the garlic and peppercorns.

TO MAKE DUCK STOCK: Place the duck neck, wing tips, and any other rejected bits in a large stockpot with 1 tablespoon black peppercorns, a 2-inch piece of ginger, 5 garlic cloves, peeled, and 5 shallots, peeled. Add water to cover. Bring to a boil, then reduce the heat and simmer for 2 hours. Remove from the heat and let stand until cool, then pour through a fine sieve, lined with cheesecloth if you wish. Discard the solids and transfer the broth to glass or plastic containers, cover tightly, and refrigerate. When chilled, the fat will congeal on the surface of the broth and can be scraped off and set aside for another purpose. Use refrigerated broth within 3 days, or freeze for up to 4 months.

The answer to “what to snack on?”: rice balls at a street stall in Vientiane, Laos.

We think that these deep-fried rice balls may originally be Vietnamese, but we’re not sure. We first had them while staying in Vientiane, in Laos. Whenever hunger struck, we’d walk down the street to a nearby market that specialized in prepared foods, and we’d pick up several rice balls. The rice ball vendor would break them open, then toss them with various fresh herbs and coarsely chopped pork skin. They were a great treat at any time of the day, a combination of savory rice, fresh tastes, and contrasting textures.

Once home, we worked on our own version of the recipe, as they seemed an ideal way to use leftover rice. In Vientiane, the balls were very large and deep-fried in oil. For our home-style version, we make them smaller and flatter. This way we can fry them in a shallow pan of hot oil and know that they’ll cook right through. We also omit the pork skin, for the sake of convenience, and instead we serve them with a little chopped savory sausage or Vietnamese pâté.

The rice balls in Vientiane had a very golden glow, which we first assumed came from using a little tomato paste, but the women in the market assured us that they used only eggs and coconut to flavor the rice. Of course, the yolks of eggs from free-range hens are very richly colored. The coconut can be omitted, but it sure makes a great little extra taste. Serve these for lunch or breakfast.

1 large egg, preferably free-range

½ teaspoon salt

½ to 1 teaspoon sugar

4 cups freshly cooked or leftover jasmine rice

¼ cup finely chopped fresh or defrosted frozen, grated coconut (optional)

Peanut or other oil for deep-frying

TOPPINGS AND CONDIMENTS

1 cup chopped cooked sausage, such as Spicy Northern Sausage (page 256) or Issaan Very Garlicky Sausage (page 258) or Vietnamese Baked Cinnamon Pâté (page 259) (optional)

Sugar (optional)

¼ cup Thai fish sauce

2 to 3 limes, cut into wedges

½ cup minced scallions

½ cup chopped coriander

2 to 3 tablespoons dried red chile flakes (optional)

ACCOMPANIMENTS

Vietnamese Herb and Salad Plate (page 68)

½ cup Vietnamese Must-Have Table Sauce (nuoc cham, page 28) (optional)

In a large bowl, whisk together the egg, salt, and sugar. Add the rice and the coconut, if using, and stir and turn to distribute the egg and coconut evenly through the rice.

Place a large heavy wok or large heavy pot on a burner and add oil to a depth of 1½ to 2 inches. Make sure the wok or pot is stable on the burner. Heat over high heat until the oil just begins to smoke, then lower the heat very slightly. A small clump of rice dropped into the oil should sink and then immediately rise back to the surface while browning but not turning black; adjust the heat as necessary.

Wet your hands, then scoop up a scant ½ cup of the rice mixture, place it in one palm, and use both hands to shape it into a flattened disk, like a hockey puck. Do not compress it; just handle it lightly, so that the grains of rice are not squashed and can still puff up in the hot oil. Using a slotted spoon, slide the patty into the hot oil. It will spatter and hiss mildly as it gives off moisture into the oil. Cook for 2 to 2½ minutes, turning it over after 45 seconds to 1 minute to ensure even browning and cooking. The rice on the outside of the ball will puff and turn golden as it cooks; you want it to be a medium brown, not just pale golden. When the patty is done, use the slotted spoon to lift it out of the oil, pausing to let excess oil drain off, and transfer it to a paper towel–lined plate or rack. Shape and cook the rest of the rice; you may have room to fry 2 patties at a time. You will have about 10 rice patties.

To serve, let the patties cool a little, so you can handle them. Put out a platter with piles of toppings on it, along with the salad plate, and, if you like, provide small individual condiment bowls of dipping sauce. Place 2 rice patties on each plate, or let guests serve themselves. Guests can dress their rice as they please. To prepare an individual serving, break open a patty into 3 or 4 pieces. Top with a generous sprinkling of chopped sausage or pâté, if using, then sprinkle on a little sugar if you wish, a dash of fish sauce, a generous squeeze of lime juice, and a dense sprinkling of scallions and coriander leaves. Top with sprinkled dried red chile flakes if you wish.

Use the lettuce and herb leaves to pick up pieces of the rice patties; drizzle on the table sauce if you wish. Eat the rice balls with your hands, the traditional way, or with a fork and spoon.

MAKES 10 rice balls; serves 5

Leftover rice is the source of many wonderful rice dishes, from fried rice to these crisp savory rice crackers. Before the days of rice cookers, jasmine rice was often cooked in a heavy pot with a curving bottom that sat directly on the fire. The crust of toasty golden brown rice that stuck to the bottom of the pot became a treat in itself.

Drying sheets of cooked rice can yield a similar crispy toasted rice. The dried-out rice is broken into bite-sized pieces and then put away in well-sealed containers. Just before serving, the rice pieces are deep-fried until they puff, to make crispy crackers. It’s a technique found in China and Thailand, as well as in many other parts of the rice-eating world. Where sticky rice is a staple, in Laos, and northern and northeast Thailand, it’s shaped into flat disks that are dried, then deep-fried to make rice cakes known as khao khop.

Crispy rice crackers can be stored in a well-sealed container for several days. They make a handy pantry item: Drop them into hot soup as croutons, or serve them like chips, with salsa. In Laos, they are commonly eaten as an accompaniment to hot noodle soup.

2 cups or more just-cooked jasmine rice

Peanut or other oil for deep-frying

Use warm to hot rice. With a rice paddle or wooden spoon, spread the rice onto a lightly oiled baking sheet to make a layer about ½ inch thick. Press down with your paddle to compact the rice so that it sticks together. Don’t worry about ragged edges, as you will be breaking up the rice into large crackers after it dries.

Place the baking sheet in a preheated 350°F oven and immediately lower the temperature to 250°F. Let dry for 3 to 4 hours. The bottom will be lightly browned.

When the rice is dry, lift it off the baking sheet in pieces. Break it into smaller pieces (about 2 inches across, or as you please), then store well sealed in a plastic bag until ready to use.

To fry the crackers, heat 2 to 3 inches of peanut oil in a large well-balanced wok, deep fryer, or large heavy pot to 325° to 350°F. To test the temperature, drop a small piece of fried rice cake into the oil: It should sink to the bottom and immediately float back to the surface without burning or crisping. Adjust the heat as necessary.

Add several pieces of dried rice cracker to the hot oil and watch as the rice grains swell up. When the first sides stop swelling, turn them over and cook on the other side until well puffed and just starting to brown (about 30 seconds in all). Use a slotted spoon to remove them immediately to a paper towel–lined platter or rack to drain. Gather up any small broken pieces; these make delicious croutons. Fry the remaining pieces of rice cracker the same way, making sure that the oil is hot enough each time. Serve hot and fresh, to accompany soup or salsa. Store in a cool place for no more than a week.

NOTE: You can also use freshly cooked sticky rice to make these crackers.

A new road links this Hmong village with the Thai towns lower down the river; before there were only footpaths between them.

Sticky rice being harvested in November around Chiang Mai.

A Lisu child dressed in her New Year’s finery. Grilled sticky rice cakes are eaten in quantity during the festivities.

The Shan use rice or mung beans to make a wonderful snack, usually eaten in the morning, called khao foon. They snack in the market, or take a bag home.

Khao foon makers are specialists, like people who make tofu. The rice or beans are soaked in water, then ground to a smooth paste. The paste is cooked over low heat, stirred constantly. A coagulant is added (as it is in cheese or tofu making), and the paste thickens into a firm jellylike texture, with a neutral to slightly sour taste. If it’s made from rice, khao foon is creamy white to pale yellow in color; if it’s made from mung beans (as it is in the southern Shan State), it’s a beautiful pale green. Khao foon is served in cubes, chunks, or slices, in a bowl. On top go all kinds of condiments and flavorings, from finely chopped scallions to chile paste, ginger paste, dark vinegar, chopped roasted peanuts, and more.

We ate the rice version of khao foon in Mae Sai and the mung bean version near Inle Lake, in the Shan State. The Phuan people, in the area around Phonsavan in eastern Laos, make a similar rice jelly that they call khao poon, as do the Bai near Dali, where it’s called mi lin fen. It’s sold in stalls in the market as a morning meal, topped in Dali with dark vinegar, and in Phonsavan with herbs, chopped scallions, and chile paste. The Phuan one we tried was very mild, with none of the fermented taste of the khao foon we’d eaten in Mae Sai.

In Mae Sai one late afternoon (see Border Town, page 92), Chad’s niece Shieng took me off on her motorbike to a Tai Koen household that specialized in making khao foon. The family had moved to Thailand from the Shan State twenty years earlier. They were known, Shieng told me, as the finest khao foon makers in the area. By their beautiful traditional teak house, huge cauldrons of pale rice batter were slowly firming up into smooth jelly. In a few hours, the jelly would set completely; early next morning, well before dawn, it would be cut into chunks and carried off to the market to be sold.

In the southern, part of Shan State, khao foon is made with mung beans, so it’s pale green in color. It’s an appetizing sight in the morning market in Kalaw, Shan State, Burma.

This is a simple, straightforward version of Thai fried rice, a dish we usually eat at least once a day in Thailand, and about half that frequently at home. While we like other versions of fried rice, for us it is the Thai version that is far and away the best. Maybe it is the combination of fish sauce, jasmine rice, and the taste of the wok. Maybe it is the squeeze of lime and fish sauce with chiles (prik nam pla) as condiments. Maybe it is the hundreds of different places where we’ve happily sat eating Thai fried rice, the totality of all those nice associations. Whatever it is, we love it. Thai fried rice is one of life’s great simple dishes.

The following recipe is for one serving. If you have a large wok, the recipe is easily doubled to serve two; increase the cooking time by about 30 seconds. If you are serving more than two, prepare the additional servings separately. The cooking time is very short, so once all your ingredients are prepared, it is easy to go through the same cooking process—simply clean out the wok and wipe it dry each time. It is much easier to prepare khao pad when your wok isn’t overly full. Total preparation time is about 8 minutes; cooking time is about 4 minutes.

2 tablespoons peanut oil

4 to 8 cloves garlic, minced (or even more if not using optional ingredients)

1 to 2 ounces thinly sliced boneless pork (optional)

2 cups cold cooked rice (preferably Thai jasmine)

2 scallions, trimmed, slivered lengthwise, and cut into 1-inch lengths (optional)

2 teaspoons Thai fish sauce, or to taste

GARNISH AND ACCOMPANIMENTS

About ¼ cup coriander leaves

About 6 thin cucumber slices

1 small scallion, trimmed (optional)

2 lime wedges

¼ cup Thai Fish Sauce with Hot Chiles (page 33)

Heat a large heavy wok over high heat. When it is hot, add the oil and heat until very hot. Add the garlic and stir-fry until just golden, about 20 seconds. Add the pork, if using, and cook, stirring constantly, until all the pork has changed color completely, about 1 minute. Add the rice, breaking it up with wet fingers as you toss it into the wok. With your spatula, keep moving the rice around the wok. At first it may stick, but keep scooping and tossing it and soon it will be more manageable. Try to visualize frying each little bit of rice, sometimes pressing the rice against the wok with the back of your spatula. Good fried rice should have a faint seared-in-the-wok taste. Cook for approximately 1½ minutes. Add the optional scallions, then the fish sauce, and stir-fry for 30 seconds to 1 minute.

Turn out onto a dinner plate and garnish with the coriander. Lay a row of cucumber slices, the scallion, and the lime wedges around the rice. Squeeze the lime onto the rice as you eat it, along with the chile sauce—the salty, hot taste of the sauce brings out the full flavor of the rice.

SERVES 1

NOTES: Once you’ve tossed the garlic into the hot oil, you can also add about ½ teaspoon Red Curry Paste (page 210 or store-bought) or Thai Roasted Chile Paste (nam prik pao, page 36 or store-bought). It adds another layer of flavor and a little heat too.

Fried rice is very accommodating: If you have a little tomato or spinach or other greens, finely chop them and add after you’ve begun to stir-fry the rice.

Many people (we’re among them) like to eat a fried egg on top of their fried rice. Wipe out your wok, heat about 2 teaspoons of oil, and quickly fry the egg, then turn it out onto the rice. It’s delicious.

This Vietnamese version of fried rice is another great way to make a meal out of leftover rice. We first tasted it in Hue, on a rainy February day, at a street stall near the Perfume River. It was warming and sustaining, just what we were craving.

The rice is flavored with a paste of lemongrass, dried shrimp, and shallots. If you are not a dried shrimp lover, omit them and increase the fish sauce slightly.

4 cups cold cooked jasmine rice

1 tablespoon dried shrimp, soaked in a little hot water for 5 minutes

1 stalk lemongrass, trimmed and minced

1 small red onion, minced

3 shallots, minced

1 teaspoon sugar

Pinch of salt

2 tablespoons peanut or vegetable oil

2 tablespoons minced garlic

3 scallions, trimmed, smashed flat with the side of a cleaver, cut lengthwise into ribbons, and then cut crosswise into 2-inch lengths

2 tablespoons Dry-Roasted Sesame Seeds (page 308)

1 tablespoon Vietnamese or Thai fish sauce, or to taste

2 tomatoes, sliced, or 1 small European cucumber, thinly sliced

½ cup coarsely chopped coriander

Freshly ground black pepper

ACCOMPANIMENTS

Vietnamese Herb and Salad Plate (page 68) (optional)

Vietnamese Must-Have Table Sauce (nuoc cham, page 28)

Place the rice in a large bowl. Wet your hands with water, then break up any clumps of rice with your fingers. Set aside.

Place the shrimp and its soaking water, the lemongrass, onion, and shallots in a large mortar, add the sugar and salt, and pound to a paste. Alternatively, use a blender to grind the ingredients, adding just enough warm water to make a puree. Turn the paste out into a small bowl and set aside.

Heat a large heavy wok over high heat. Add the oil and heat until hot. Toss in the garlic and stir-fry for 10 seconds. Add the lemongrass paste and stir-fry for about 3 minutes, until it is golden. Add the scallions and stir-fry briefly. With wet hands, sprinkle the cold rice into the wok and stir-fry vigorously for 1 to 2 minutes, tossing and pressing the rice against the sides of the wok until all of it has been exposed to the hot pan. Add the sesame seeds and fish sauce and stir-fry for another 20 seconds or so. Taste and add a little more fish sauce if you wish, then turn out onto a plate. Arrange the tomato or cucumber slices around the rice and top with the coriander leaves and a generous grinding of pepper.

Serve with the salad and herb plate if you wish and with small condiment bowls of the table sauce, so guests can sprinkle it on as they eat.

SERVES 2 to 3 as a simple lunch