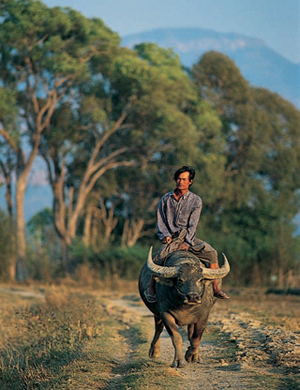

You don’t see herds of Herefords grazing their way along the banks of the Mekong, nor Aberdeen Angus, for that matter. But you do see some fine-boned Asian cattle grazing, and lots of water buffalo, lazing in mud wallows, calmly lifting their big heads with black swept-back horns to watch you as you walk by. Water buffalo are the region’s beast of burden, used for plowing and milking, and, eventually, for meat. The buffs are docile and amiable, a good thing, given their size. They graze in the rice stubble and along the edges of the road, often tended or watched by village children.

The recipes we’ve grouped together here all call for beef, though some of them have their origins in recipes using the meat of the water buffalo. Along the Mekong, beef is grilled, stir-fried, or sun-dried and then deep-fried (see Fried Beef Jerky, page 218), but rarely stewed. One exception is a delicious slow-simmered dish from Yunnan, Hui Beef Stew with Chick-peas and Anise (page 231), very warming on a cold winter’s evening.

Beef and water buffalo meat are sometimes eaten spiced and uncooked in northern Thailand, the Shan State, Laos, and parts of Yunnan. The meat is first minced or sliced, then dressed with chiles and salt (see Dai Beef Tartare with Pepper-Salt, page 230) or with lime juice (see Chiang Mai Carpaccio, page 230).

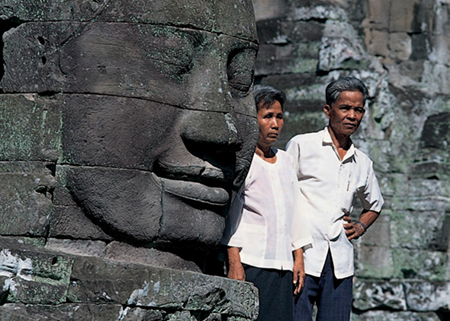

The Khmer empire once stretched from western Thailand to the Mekong Delta. Many Khmer people who still live in the Mekong Delta region are descendants of the Khmer who controlled the area until two centuries ago. In the countryside near Tra Vinh lies Ba Om, an important Khmer temple lively with monks of all ages.

Water buffalo are used for plowing and, when the day’s work is done, for a slow ride home.

One of the huge carved faces at the Bayon, in Angkor Thom, dwarfs Khmer visitors.

With its beautiful carvings and lovely proportions, the temple of Banteay Srei is perhaps the most aesthetically pleasing of the ancient Khmer temples.

In northeast Thailand, sun-drying marinated beef produces neua kaem, salty strips of flavorful dried beef. These days it’s not dried out completely, unlike jerky, though in earlier times perhaps it was, a way of keeping meat indefinitely without spoilage. The drying helps it keep for a few days without refrigeration, changes the texture, and intensifies the taste of the meat and the flavorings it’s marinated in. Though it’s often eaten dry, like jerky, neua kaem is even more delicious if briefly fried; you can also grill it, brushed with a little oil.

This aromatic marinade is a pounded combination of coriander seeds, coriander roots, lemongrass, and seasonings that we also use as a rub for beef before grilling.

Traditionally, the beef strips are coated in the marinade, then sun-dried. But sun-drying needs hot sun and a way of protecting the meat from contamination, so we suggest that you simply slow-dry the beef strips in a warm oven. It takes about 6 hours in the oven to get semidry, the texture we prefer. If you want a completely dried-out jerky (for taking on a camping trip, say), leave the strips in the oven for 10 to 15 hours (see Notes).

You can make the dried beef, then store it in the freezer until you want to serve it. It makes a great last-minute dish.

1 pound boneless lean beef (such as tenderloin, flank steak, or center round)

MARINADE

½ teaspoon coriander seeds

1 tablespoon minced lemongrass (about 1 stalk)

½ teaspoon salt

3 tablespoons chopped coriander roots

2 medium cloves garlic, chopped

½ teaspoon black peppercorns

1 teaspoon sugar

2 tablespoons Thai fish sauce, or more as needed

Peanut oil or other oil for deep-frying

Slice the beef into very thin strips and set aside in a shallow bowl.

Using a large mortar and a pestle, pound the coriander seeds to a coarse powder, then add the lemongrass and pound until well broken down. Add the salt and coriander roots and pound to a coarse paste, then add the garlic, peppercorns, and sugar and pound to a paste. Stir in the fish sauce, then pound a little to make a smooth paste. If it seems very dry, add a little more fish sauce, or a little water. You want the paste to be moist and smooth enough to coat the meat. You’ll have about 3 tablespoons marinade.

Alternatively, you can use a blender to make the paste. (With a processor, it’s difficult to get a fine-enough texture.) You may need to use a spice grinder or coffee grinder to grind the coriander seeds and pepper first, then add the ground spices to the other marinade ingredients in the blender and reduce to a paste. Use a spatula to scrape the sides down as necessary.

Add the marinade to the meat and toss and turn to coat the meat thoroughly. If you have time, cover the meat and refrigerate for at least 2 hours, or as long as overnight.

Preheat the oven to 150ºF. Drain off any liquid that has been drawn out of the meat. Place a rack over a baking sheet (to catch any drips), arrange the pieces on the rack, laying them as flat as possible, and place in the upper third of the oven. Let dry for 6 hours, leaving the oven door propped open several inches to let moisture escape.

After 6 hours, the meat will have changed color right through and it will be drier, but not completely dried out. This is the ideal texture, we think, for making fried jerky. You can fry it immediately, or cool it and store it in the freezer in a well-sealed bag or container until ready to use. Bring the jerky back to room temperature before frying.

Place several plates lined with paper towels near your stovetop and have tongs or long chopsticks handy. Place the oil in a well-balanced (not tippy) wok or a large heavy skillet: You want the oil to be about ½ inch deep in a skillet, or slightly more at the deepest point of the wok. Heat the oil until it’s just starting to smoke. Gently slide about one quarter of the meat into the wok or skillet and fry for about 30 seconds, turning and moving it constantly with your tongs or chopsticks. Lift the meat out onto a paper towel–lined plate.

Bring the oil back to almost-smoking hot and cook the remaining meat in batches. Serve hot or at room temperature as a snack or as part of a rice meal.

SERVES 6

NOTES: Once you have finished frying, place the wok or skillet at the back of the stove until the oil has cooled to room temperature, then pour the oil through a piece of cheesecloth into a glass jar and store, covered, in the refrigerator.

If you want very dry jerky, traveling food, leave the strips in the oven for 10 to 12 hours, or until they are very lightweight and dry. (One pound of meat will give you about ¼ pound dry jerky.) This makes good food for camping or hiking. (It’s salty, so you’ll want to know you have plenty of drinking water.)

To use this marinade for grilled beef, rub over a piece of beef tenderloin, then place the beef under a preheated broiler or on a hot grill. Broil or grill, turning halfway through the cooking, to the desired doneness. Remove from the heat and let stand for 10 minutes. Serve thinly sliced, with Lime Juice Yin-Yang (page 129), or as a grilled beef salad, tossed with thinly sliced shallots and a lime juice and fish sauce dressing.

You can use the same recipe to make fried pork jerky; increase the sugar to 2 teaspoons and, if you wish, omit the lemongrass and coriander seeds. This is a very delicious plain country version.

Sao Pheha (see Phnom Penh Nights, page 242) introduced me to several easy dishes from the Khmer home-cooking repertoire. This was perhaps the simplest, and also the most surprising. It’s a stir-fry in which ginger has the role of featured vegetable, warming and full of flavor. The ginger is cut into julienne twigs and then fried with a little beef. The result is a mound of beef slices and tender ginger, all bathed in plenty of gravy, a great companion for rice.

Be sure to buy firm ginger for this dish (ginger with wrinkled skin will be tough and stringy), and, if there’s a choice, young ginger rather than the tan mature ginger. Serve with a sour stew or soup, such as Khmer Fish Stew with Lemongrass (page 181) or Buddhist Sour Soup (page 58), and some simple greens, such as Classic Mixed Vegetable Stir-fry (page 151).

Generous ½ pound boneless sirloin, eye of round, or other lean beef

½ pound ginger, preferably young ginger

3 tablespoons vegetable or peanut oil

3 to 4 cloves garlic, smashed and minced

2 tablespoons Thai fish sauce

2 teaspoons sugar

Thinly slice the beef across the grain and set aside. Peel the ginger, then cut it into fine matchstick-length julienne (this is most easily done by cutting thin slices, then stacking these to cut into matchsticks). You’ll have about 2 cups.

Heat a wok over medium-high heat. Add the oil and, when it is hot, add the garlic. Cook until golden, 20 to 30 seconds. Add the meat and stir-fry, using your spatula to separate the slices and to expose them all to the heat, until most of the meat has changed color. Add the fish sauce and sugar, toss in the ginger twigs, and stir-fry until just tender, 4 to 5 minutes. Serve hot with rice.

SERVES 4 with rice and another dish

New foods can be intimidating, scary even, especially if they’re soured or fermented, or transformed in a way that’s unfamiliar. Those of us who were raised in some blend of European–North American culinary tradition tend to love cheese. The fact that it’s a fermented product doesn’t bother us—in fact, for many of us, the smellier, the better. But for many Southeast Asians, the first reaction to cheese, or yogurt, is an appalled aversion: “Yuck!” sums it up.

Similarly, when we venture into traditional fermented foods from other cultures, we often have a hard time learning to like them. The Japanese fermented soybeans, natto, sour, slimy, and, yes, delicious, come to mind. So does stinky bean curd, zhou doufu, in China.

In Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam, the precursor to fish sauce is a very strong tasting fermented fish paste, with bits of fish floating in a briny liquid. In Cambodia it’s known as prahok, in Thailand as pla raa, in Laos and Issaan as padek, in Vietnam as mam. Fish sauce was originally the liquid poured or pressed from fish paste (nuoc mam, for example, means “liquid from mam”). Though salty fish sauce–like flavorings can in fact also be made with fruits or vegetables, salted and fermented, prahok, pla raa, padek, and mam need fish. The fish are packed with salt, and often rice bran or rice powder, in a ceramic barrel and left to ferment. It’s a way of preserving the catch and supplying amino acids in a diet high in rice and vegetables and low in animal products.

Padek and prahok are still made in the countryside, and people raised with them can’t live without their punchy, salty kick (the closest taste analogy is preserved anchovies). Many of the Lao and Khmer dishes in this book were originally made with padek or prahok instead of fish sauce (though, we’re always told, you must never use padek to make laab). With more people living in cities, fewer people in Thailand seem to be eating pla raa or padek. For one thing, you need to be in the countryside to make it. Also, it’s now become much easier to buy a bottle of fish sauce than to make your own, though they don’t have the same taste, not at all.

As for foreigners, the assertive salty fermented fish taste of padek or prahok or pla raa or mam is more than many are prepared to take on. All of which is to say that we’ve left out the padek or prahok or pla raa or mam. For a dish with a strong padek-type flavor, try Issaan Salsa with Anchovies (page 38). It’s salty and delicious when eaten with rice, very intense, almost overpowering, on its own.

Beside many Khmer temples lies a calm pond sheltered by tall trees. Here at Ba Om temple, a Khmer man fishes in the temple pond.

One dish that lends itself to a convivial evening with friends is hot pot. It’s like fondue, but with the ingredients cooked in a hot broth. It’s a fun way to eat, and once the ingredients and the broth are on the table, the host is free to join the party.

Although I first ate Cambodian Hot Pot on a warm tropical night at a small streetside restaurant in Phnom Penh, it is a great anytime-of-year meal. We sat, four of us, on stools around a low table set out on the sidewalk. Out came the hot pot, full of broth. The flame was lit under it and soon the broth was bubbling. We had ordered a simple array of ingredients, and they came on two platters: some thinly sliced beef, chopped greens, fresh herbs, mushrooms, a coil of soft noodles, some dipping sauces. Using chopsticks, we dropped a little meat and a few mushrooms into the broth, then began fishing treasures out and eating them. The pace was leisurely. Gradually, in a rhythm of fishing out cooked morsels and adding more, we worked our way through the platters. Finally the noodles went in. They simmered briefly, then we each ended with a bowl of richly flavored noodle soup, carefully ladled out from the hot pot, a wonderful way of finishing the feast.

Use the recipe below to get you started; feel free to add ingredients to the platter or to improvise other sauces, as you wish.

Serve wine or, more traditionally, very weak whiskey-and-sodas with this meal. Put out a platter of raw vegetables—cucumber slices, leaf lettuce, and carrot sticks—so guests can chew on something crisp as they wait for their next mouthful from the hot pot.

BROTH

2 pounds oxtails or ¾ pound stewing beef, coarsely chopped into 8 pieces

8 cups water

3 shallots, coarsely chopped

4 cloves garlic, coarsely chopped

10 black peppercorns

1 teaspoon salt

1 tablespoon Thai fish sauce

3 scallions, trimmed and cut into 2-inch lengths

PLATTER

¾ pound to 1 pound boneless beef, thinly sliced

2 cups assorted mushrooms (such as button, oyster, and portobello), cleaned and cut into large bite-sized pieces

4 sawtooth herb leaves

1 cup Asian or sweet basil leaves

3 sprigs rice paddy herb (rau om)

2 cups loosely packed coarsely chopped romaine lettuce or napa cabbage

2 large eggs (optional)

1 pound fresh egg noodles or ½ pound dried rice noodles

CONDIMENTS AND SAUCES

Thai fish sauce

2 tablespoons minced bird chiles

Yunnanese Chile Pepper Paste (page 27), Fresh Chile-Garlic Paste (page 26), or store-bought Sriracha sauce (see page 26)

Lime wedges

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

To prepare the broth, place the meat in a large pot with cold water to cover. Bring to a boil and boil for 2 or 3 minutes, then drain. Rinse both the pot and meat, then place the meat back in the pot. Add the 8 cups water, shallots, garlic, and peppercorns and bring to a boil. Skim off and discard any foam, then lower the heat and simmer, halfcovered, for 1 hour.

Add the salt and fish sauce and simmer for another few minutes, then taste for salt and adjust if necessary. Remove from the heat.

Remove the meat from the broth. Pull the meatiest bits off the oxtail bones and set aside; discard the bones. Or, if using stewing beef, set aside. Strain the broth through a fine strainer or a colander lined with cheesecloth and discard the solids. You should have about 6 cups broth; if necessary, add water to make a total of 6 cups liquid. If you have time, set the broth aside to cool, refrigerate for 2 hours, and then skim off the surface fat. (The broth can be made ahead and stored in a well-sealed nonreactive container for 3 days in the refrigerator or up to 2 months in the freezer. The meat can be stored in a well-sealed container for up to 3 days in the refrigerator.)

About 30 minutes before serving, prepare the platter ingredients and set out on one large or several smaller platters. Place the eggs, if using, uncracked, in a bowl. If using fresh noodles, rinse them off and arrange in several coils on a plate. If using dried rice noodles, soak in warm water for 20 minutes, then drain and coil on a plate. Set out a condiment bowl, a soup bowl, a plate, a pair of chopsticks, and a soupspoon for each guest.

Just before serving, reheat the broth. If you used stewing beef, slice the meat. Add some or all of the reserved oxtail or stew meat and the scallions to the broth. Lower the heat to a simmer while you set up a hot pot or other pot heated over a low flame (see Note). Pour the hot broth, with the meat and the scallions, into the hot pot. The heat should be enough to keep the broth at a slightly bubbling simmer. Invite your guests to the table.

Begin by tossing some of the sawtooth herb and rice paddy herb into the broth. Invite your guests to add a few items from the platter to the soup; then, a few minutes later, invite them to “go fishing” with their chopsticks for the cooked morsels, which they can lift out onto their plates and eat, perhaps after dabbing on one or more condiments. As the meal goes on, gradually add more herbs and greens to the soup.

When the platter is just about empty, break the eggs, if using, into the bowl, beat them briefly with chopsticks, and add them to the soup. Stir to spread the skeins of egg. Toss in the noodles, and stir gently. When the fresh noodles are tender or the dried ones are hot, use a ladle and chopsticks to serve the soup and noodles to each guest. Invite them to sprinkle any remaining fresh basil leaves onto their soup as they eat.

SERVES 4 to 6

NOTE: The traditional serving implement used for hot pot is available from Chinese and Vietnamese cookware shops. These days, the most commonly available are lightweight aluminum pots. A hot pot has a cylindrical “chimney” in the center that is placed over a can of Sterno or other small flame. Around the chimney is the doughnut-shaped “pot” in which the broth and other ingredients simmer, heated by the chimney. You can also use a large heatproof pot set over a Sterno flame, fondue style.

SPICY GRILLED BEEF SALAD

The name of this substantial dish means “beef with dripping liquid.” The beef is lightly grilled or broiled, then thinly sliced. The slices are cooked a little more in a hot broth-based dressing before being tossed with sliced shallots and fresh mint leaves. The meat emerges tender, moist, and lightly spiced with chiles. It makes a great main-course dish accompanied by sticky rice or aromatic jasmine rice.

SALAD

One 1-pound boneless beef sirloin steak, approximately ¾ inch thick

1 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

½ cup beef or chicken broth

3 tablespoons fresh lime juice

2 tablespoons Thai fish sauce

1 teaspoon sugar

1 teaspoon Roasted Rice Powder (page 308) (optional)

⅓ cup thinly sliced shallots, separated into rings

4 scallions, trimmed, sliced lengthwise in half, and cut into ½-inch lengths

2 bird or serrano chiles, minced

½ cup mint leaves

ACCOMPANIMENTS: CHOOSE TWO OR THREE

1 small cabbage, cored, cut into wedges, and separated into leaves

8 to 10 leaves tender leaf or Bibb lettuce

4 to 6 leaves napa cabbage, cut crosswise into 1- to 2-inch slices

5 or 6 yard-long beans, trimmed, cut into 2-inch lengths, and (optional) blanched in boiling water for 1 minute

1 European cucumber, cut into ¼-inch slices

2 or 3 scallions, trimmed and sliced lengthwise in half

Prepare a grill or preheat the broiler. Rub the meat with the black pepper. If grilling, place the meat 3 to 4 inches above the coals or flame; if broiling, place in the broiler pan about 3 inches below the element. Grill or broil until rare, 2 to 3 minutes per side. Very thinly slice the meat across the grain.

In a medium saucepan, mix the broth, lime juice, fish sauce, and sugar together and bring to a boil over high heat. Toss in the rice powder and meat and quickly stir to coat the meat. Immediately remove from the heat and transfer the meat and dressing to a large bowl (you must be quick so as not to overcook the beef). Add the shallots, scallions, chiles, and mint and toss gently. Let stand while you arrange your choice of accompaniments on a platter.

Mound the salad on a plate and pour the extra dressing over. Serve with the platter of accompaniments and plenty of jasmine or sticky rice.

SERVES 4 to 6 with rice

GRILLED LEMONGRASS BEEF

Bo Bay Mon means “Beef in Seven Ways” and is the name given to a style of restaurant found in Ho Chi Minh City and now, lucky for us, in some North American cities. It’s a place to go for a special occasion, especially in a culture that doesn’t eat lots of meat, for each of the dishes on the menu is made with beef. Sometimes the restaurant adds several more dishes to the classic lucky seven.

We love the taste of grilled lemongrass, so we generally choose this grilled beef whenever we’re dining at a Vietnamese restaurant, Bo Bay Mon style or otherwise. Tender slices of beef are marinated in a lemongrass-based marinade and then grilled or broiled. Serve as one of several dishes with rice, as a topping for noodles, or as an ingredient in rice paper roll-ups (see Note).

MARINADE

2 stalks lemongrass, trimmed and minced

2 to 3 cloves garlic, finely chopped

2 shallots, finely chopped

1 bird or serrano chile, finely chopped

2 tablespoons Vietnamese or Thai fish sauce

1 tablespoon fresh lime juice

1 tablespoon water

1 tablespoon roasted sesame oil

1 pound beef rump roast or eye of round, trimmed of all fat

2 tablespoons Dry-Roasted Sesame Seeds (page 308)

ACCOMPANIMENTS

Vietnamese Herb and Salad Plate (page 68)

1 cup Vietnamese Peanut Sauce (nuoc leo, page 28) or Vietnamese Must-Have Table Sauce (nuoc cham, page 28)

To prepare the marinade, combine the lemongrass, garlic, shallots, and chile in a mortar and pound to a paste. Or, combine in a blender and blend, adding a little water if necessary to make a paste. Transfer the paste to a bowl, add the fish sauce, lime juice, and water and blend well. Add the sesame oil and stir well. Set aside.

Cut the meat into very thin slices (less than ⅛ inch) against the grain (this is easier if the meat is cold). Then cut the slices into 1½-inch lengths. Place the meat in a shallow bowl, add the marinade, and mix well, making sure that the meat is well coated. Cover and marinate for 1 hour at room temperature or up to 8 hours in the refrigerator.

If using wooden skewers, soak them in water for 30 minutes before using. Prepare a grill or preheat the broiler.

Thread the pieces of meat onto wooden or fine metal skewers and sprinkle with the sesame seeds. Lightly oil the grill rack or broiler pan. Grill or broil the meat for 1 minute per side for medium-rare.

Arrange on a platter and serve with the salad plate and peanut sauce or table sauce.

SERVES 4 to 6 as part of a rice or noodle meal

NOTE: To serve the beef in rice paper roll-ups, set out, in addition to the salad plate and dipping sauce, about 25 dried rice papers, preferably small rounds; 1 pound rice vermicelli, soaked in warm water for 15 minutes, drained, cooked in boiling water, and drained; ¼ cup Dry-Roasted Peanuts (page 308), finely chopped (optional); and 2 bird or serrano chiles, minced (optional). Make sure there is plenty of soft leaf lettuce on the salad plate, and set out a bowl of warm water for wetting the rice papers. Show your guests how to roll up the beef: Moisten a rice paper in warm water until soft. Place a lettuce leaf on your plate and lay the rice paper on it. Place a small bunch of noodles, perhaps some minced chiles or chopped peanuts, or whatever else you please, on it, then add some herb sprigs and pieces of grilled beef. Roll up, tucking in the sides. Use the lettuce leaf to hold the roll. Dip it in the sauce, or drizzle on a little sauce with a spoon, and eat.

It’s terrible to admit in an opener to Angkor Wat, but I’m not a big temple person. I’m terrible with iconography, and with old temples and ruins my imagination is slow to get into gear. I want kitchens, food, clothing, agriculture, daily life.

But don’t get me wrong, I loved Angkor Wat; I mean, I loved being there. The temples are human in scale, not overpowering, while the surrounding countryside is jungly, vast, and mysterious. These days the whole Angkor region is treated as a national park. Each day I entered, I was required to pay a twenty-dollar entrance fee, plus six dollars for a guide. The system was fine by me: Dawn to dusk I had a guide who drove me around on the back of his motorbike.

The first few days, we visited temple after temple on Heang Ly’s motorbike. He got me to Bayon at sunrise, Angkor at sunset; we did the “small circuit,” and then started on the “long circuit.” Our days were long, varooming around on the motorbike, climbing up and down temple stairs. But as we went along, we talked, and we got to be friends.

Heang was born near Angkor in a village a day’s walk from Siem Riep. His father had been an odd-job man in the village, fixing things, sometimes working as a doctor ministering to patients with medicinal roots and herbs, especially people suffering from allergies. Heang’s grandfather had come to Cambodia from China, so when the Khmer Rouge came through the village looking for anyone with Chinese ancestry, his father’s life was in danger. But the village people hid him; he was their friend, after all, and he helped them. His father then sent Heang and his older brother to the city, to Siam Riep, thinking they would be safer there, and they were. Heang was twelve.

Like every family in Cambodia, Heang’s family suffered much tragedy. “Salt had greater value than gold,” Heang told me one morning as we were driving along. “Gold meant nothing. There was no food to buy.” Before going to the city, Heang, like many Cambodian children, had the daily job of shepherding cows from grassy field to grassy field. Then, as now, the job was horribly dangerous because the fields were strewn with land mines. “The only thing is,” Heang explained as we were watching children one morning with a herd of cows on the road, “sometimes the cows save the children: They hit the mines before the children do.”

But Heang does more than look back. At twenty-six years old, he is an incredibly good guide. He is multilingual, intelligent, nice, funny. When I at last admitted to him that I was more interested in food than in temples, he took me to markets, to a fish-fermenting factory, and to a Vietnamese village entirely afloat on the Tonle Sap. At dawn, we no longer drove to ruins, but instead met for babah (see page 94) and talked food. Every meal had a purpose, and an explanation.

On my last day, my last morning, a different guide showed up. He had a note from Heang, explaining that he’d gotten a better offer that day, a German tour group in a minivan. I was disappointed, but pleased for him. What Heang deserves, what everyone in Cambodia deserves, is for each day to be better than the last.

One’s first sight of Angkor Wat: calm, mysterious, beautiful. In the fifteenth century, the Khmer court moved from Angkor to establish a new capital at Phnom Penh.

We learned this simple traditional dish from a friend in Chiang Mai. It’s ideal as an appetizer, or as one of several dishes in a rice meal. The transparently thin slices of beef are “cooked” by the lime juice they’re bathed in, then flavored with a scattering of distinctive tastes: minced lemongrass, shallots, and fresh ginger and herbs.

¼ pound beef tenderloin or other boneless tender lean cut

3 tablespoons fresh lime juice

¼ teaspoon salt, or more to taste

1 tablespoon minced shallots, or substitute mild onion

½ teaspoon minced lemongrass

¼ teaspoon minced ginger

¼ cup torn coriander leaves or minced mint leaves

Very thinly slice the beef across the grain (this is easier if the meat is frozen or at least well chilled), then cut the slices crosswise into bite-sized pieces, about ¾ inch long. Place in a shallow bowl with the lime juice, turn to mix well, and let stand for 5 minutes.

Lay the beef slices on a flat plate in a single layer, slightly overlapping if you wish. Pour any remaining lime juice over. Sprinkle on the salt, then sprinkle on the remaining ingredients in order, ending with the fresh herbs. Serve immediately.

SERVES 4 as an appetizer or as part of a rice meal

We’ve come across this delicious spiced minced beef several times in southern Yunnan. Each time, we used pieces of cabbage to scoop up small mouthfuls, hot and salty and good; you could also use cucumber slices. It is a great pairing with beer. Serve winter or summer, as an appetizer. If you prefer your beef cooked, then shape the seasoned meat into patties and grill or broil them (see Note).

¼ pound boneless lean beef (such as tenderloin)

½ teaspoon Chinese Pepper-Salt (page 309)

¼ cup coriander leaves, coarsely torn

ACCOMPANIMENTS

Small wedges of Savoy cabbage, parboiled, or cucumber slices or fresh leaf lettuce

Two Pepper–Salt Spice Dip (page 309)

Use a cleaver to slice the meat very thin and then to chop it until finely minced: Chop it fine in one direction, then fold it over on itself and chop fine in the other direction. Transfer to a large mortar or a food processor, add the pepper-salt, and pound or process until very smooth. Stir in the coriander leaves, or pulse briefly. Mound on a small plate, and serve with your chosen accompaniments and sticky rice or Thai-Lao Crispy Rice Crackers (page 106).

MAKES over ½ cup tartare; serves 4 as an appetizer

NOTE: If you hesitate to serve raw beef, you can shape the beef paste into small patties (this recipe makes 12 patties about ½ inch across), slide them onto small skewers if you wish, brush them with a little sesame oil, and grill or broil them. Serve as an appetizer, as one dish of many in a rice meal, or as an ingredient for wrapping in rice paper roll-ups (see Note, page 177).

Hui is the name given in China to people of Han Chinese ethnicity who are Muslim. There are large communities of Hui in western Yunnan, perhaps descendants of the soldiers of Kublai Khan’s army who swept through conquering the region in 1237. Hui cuisine has a strongly Central Asian flavor: flatbreads, simmered meats without many vegetables, and, of course, no pork, just lamb or beef. This hearty stew is great for cold winter evenings. Make plenty, because it makes wonderful leftovers. (You can also make it with lamb.)

Serve with rice or flatbreads and a plate of Yunnan Greens (page 151) or Simple Dali Cauliflower (page 158). To spice things up, put out a dish of Yunnanese Chile Pepper Paste (page 27).

2 cups dried chick-peas, 4 cups cooked chick-peas, with their cooking liquid, or 4½ cups canned chick-peas, rinsed and drained

Water

3 tablespoons peanut or vegetable oil or beef drippings

2 pounds stewing beef, cut into approximately 2-inch chunks, or substitute stewing lamb

2 cups coarsely chopped onions

2 star anise (3 if using lamb)

1 tablespoon salt, or to taste

¼ teaspoon Sichuan peppercorns, ground to a powder

2 Thai dried red chiles

4 scallions, trimmed, cut lengthwise in half, and then cut into 2-inch lengths (optional)

3 tablespoons Dry-Roasted Sesame Seeds (page 308) (optional)

If using uncooked chick-peas, place in a large pot with water to cover by 3 inches. Bring to a vigorous boil, then boil for 15 minutes. Drain, then return to the pot and add 8 cups water. Bring to a vigorous boil and skim off any foam, then reduce the heat to maintain a strong simmer and cook half-covered until the chick-peas are just tender, 2 to 3 hours. Remove from the heat and set the pot aside.

While the chick-peas are cooking, prepare the beef: In a large wok or a large heavy skillet, heat the oil or drippings over high heat. Add the meat (in two batches if your wok or skillet seems small) and sear, turning and stirring to expose all surfaces to the hot pan, until all the surfaces have changed color. Add the onions and star anise, lower the heat to medium, and cook until the onions are very soft, about 10 minutes. Add 1 teaspoon salt and the Sichuan pepper and cook for another 5 minutes. Remove the pan from the heat and set aside.

When ready to proceed, place the pot of cooked chick-peas back on the stove, or, if using previously cooked or canned chick-peas, place them in a large heavy pot. Add the meat mixture to the chickpeas, then add water, enough to just cover the meat. Add the dried chiles and the remaining 2 teaspoons salt, raise the heat, and bring the stew almost to a boil. Lower the heat and cook at a simmer, uncovered, for about 3 hours, until the meat is very tender and the chick-peas almost melting. Stir occasionally, and add extra water if the stew seems to be getting dry. (Once cooked, the stew can be set aside until 10 minutes before serving; if the wait will be longer than 2 hours, cool to room temperature, then refrigerate in a covered container, for up to 3 days. The stew can also be frozen for up to 2 months. Place it in a large pot over medium heat and bring almost to a boil before proceeding.)

About 5 minutes before serving, if you wish, stir the scallions and sesame seeds into the stew. Taste for seasonings and adjust if necessary.

SERVES 8

A few years ago, we discovered a book entirely on the subject of salt and brining in Southeast Asia, called Le Sel de la vie en Asie du Sud-est (“The Salt of Life in Southeast Asia”; see Bibliography). It discusses salt extraction in Cambodia and Thailand. It describes in detail prahok, padek, and mam, the Khmer, Lao-Thai, and Vietnamese fermented fish pastes. It discusses the modern-day fish sauces, liquid and milder than the pastes: tuk traey in Cambodia, nam pla in Thailand, nam pa in Lao, and nuoc mam in Vietnam (see Fermented Fish, page 220).

The book is a treasure, but, unfortunately, nowhere does it address one of our basic questions: What is it about fish sauce that makes it mildly addictive? We know it’s not just us. Whole nations feel the same way. And, as with olive oil, people always prefer the fish sauce they’ve grown up with, the fish sauce from their region.

In the spring of 1975, I was in Paris, staying with the uncle of a friend. He was a retired doctor of Vietnamese origin named Tanh, a longtime resident of France. His older brothers’ families were still in Vietnam. Over the years, he’d bought several apartments in Paris, just in case they ever needed to leave.

We sat in the living room watching the fall of Saigon on television. As events moved swiftly on the other side of the world, Tanh predicted that Vietnam would be cut off from trade and contact with the West for some time. “We won’t be able to get nuoc mam,” he said, “only that mild Thai fish sauce.” So he sent me off to buy what bottles of Vietnamese fish sauce I could find. Others had had the same idea; in each shop, there were only a few bottles left on the shelves. Tanh stored his carefully in the cellar.

Ten months later, on a cold gray February day, nineteen members of his family, aged six to seventy-four, arrived in Paris, on twenty-four hours’ notice, with only the clothes on their backs.

We love the array of bottled fish sauces sold at markets, but how to choose one? The best fish sauce, we think, is light colored and fairly clear (rather than dark and cloudy), contains no sugar, and has only three ingredients: anchovies, salt, water. We prefer fish sauces made in Thailand; they’re a little milder than the Vietnamese.