leafy

salad

plants

—

Mild-flavoured leaves – lettuce above all – have always been the mainstay of the traditional salad. But oh how that salad can be enriched with the spiciness of salad rocket, the subtle flavours of the chicory tribe, the glorious colours of Swiss chard and red chicories… Then there’s the sparkle of iceplant, the textures of summer and winter purslane, and the dainty beauty of curled endive. Some of the many possibilities are explored in this chapter.

Lettuce

Lactuca sativa

Lettuce is rightly one of the most widely grown salad plants. Not only is the quality and flavour of home-grown lettuce far superior to anything you can buy, but the colourful varieties now available are exceptionally decorative in the garden. Even in small gardens there is always space for a few lettuces. Pretty loose-leaf Salad Bowl types make excellent edges to vegetable and flower beds; small hearting types, such as ‘Tom Thumb’ and ‘Little Gem’, are ideal for intercropping; patches of seedling lettuce and ‘leaf lettuce’ require minimum space.

Lettuce is essentially a cool-climate crop, growing best at temperatures of 10–20°C/50–68°F. With the exception of the Asiatic stem lettuce, it does not do well in very hot climates. In most temperate climates you can grow it all year round, provided you sow appropriate varieties each season. Some protection is usually advisable for the winter crop, while in colder regions artificial heating is essential for a continuous winter supply. Where greenhouse space is limited in winter, it may be better to devote it to oriental greens grown as seedlings, salad rocket, Texsel, endives and chicories. Compared to lettuce, these are far more tolerant of the low light levels and damp weather typical of northern-latitude winters and probably far more nutritious than most winter lettuce varieties.

–––––

Types of lettuce

Lettuces can be divided roughly into hearting and non-hearting types, with a few intermediate, semi-hearting varieties. The principal hearting types are the tall cos or ‘romaine’ lettuce, and the flat ‘cabbage’ type, subdivided into ‘butterhead’ and ‘crisphead’ lettuce. Non-hearting types include the loose-leaf Salad Bowl varieties and stem lettuce. While lettuces are predominantly green, there are now red and bronze forms in virtually every type of lettuce. For varieties, see here.

Cos These are large, upright lettuces with long, thick, crisp, distinctly flavoured leaves forming a somewhat loose heart. They are slower-maturing than other types, but stand hot and dry conditions well without running to seed, besides tolerating low temperatures. Several varieties are frost hardy and can be overwintered, and some are suitable for sowing thickly as leaf lettuce (see here). Cos lettuces keep well after cutting. ‘Semi-cos’ lettuces are a smaller type, exemplified by ‘Little Gem’, a compact variety notable for its sweet, crisp leaves – and arguably the best flavoured of all lettuces.

Butterhead This is the softer type of cabbage lettuce, typified by a flat, round head of gently rounded leaves with a buttery texture and mild flavour. They tend to wilt quickly after picking. Butterheads generally grow faster than crispheads, but are more likely to bolt prematurely in hot weather. While mainly grown in the summer months, they are reasonably well adapted to the short days of late summer and autumn, and many winter varieties are in this group.

Winter butterhead

Crisphead This group of cabbage lettuce is characterized by crisp-textured, often frilled leaves. The term Iceberg has been adopted for large crispheads sold with the outer leaves trimmed off, leaving just the crisp white heart. Crispheads generally take about ten days longer than butterheads to mature but stand well in hot weather without bolting – especially the American Iceberg varieties. Crispheads keep reasonably well after picking. Many are considered flavourless, but an exception is the group loosely known as ‘Batavian’. Of European origin, they often have reddish-tinged leaves and tend to be relatively hardy.

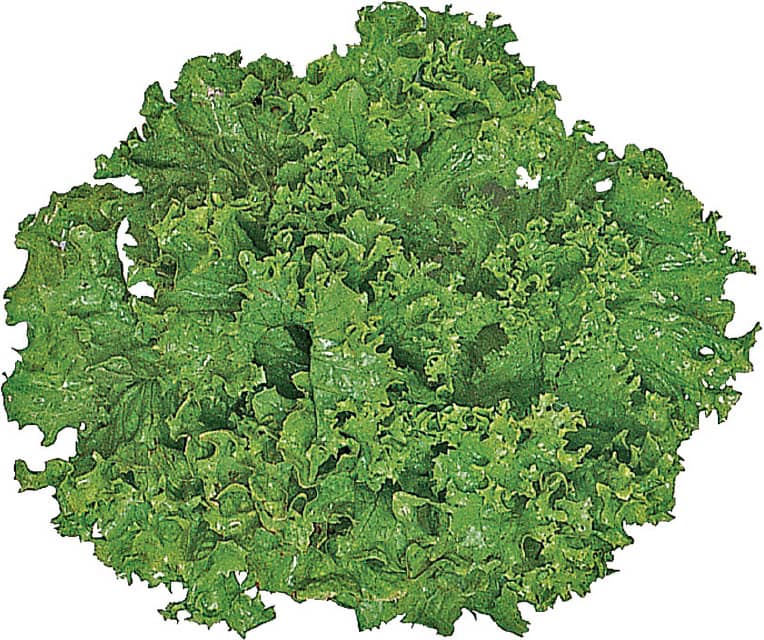

Loose-leaf Lettuces in this group form only rudimentary hearts, but produce a loose head of leaves that can be picked individually as required. The heads normally resprout if cut about 21/2cm/1in above ground. The group are also known as ‘gathering’ or ‘cutting’ lettuces, or Salad Bowl types, after the variety of that name. The leaves are often deeply indented (the ‘oak-leaved’ varieties closely resemble oak leaves) while others, notably the beautiful red and green Lollo varieties, which originated in Italy, are deeply curled. Loose-leaf lettuces are generally slower to bolt than hearting lettuce, which, coupled with their ability to regenerate, gives them a long season of usefulness. The central leaves of reddish-tinged varieties tend to become darker-coloured with successive cuts. Loose-leaf types are suitable for cut-and-come-again seedling crops. Most are reasonably hardy, and seem less prone to mildew than other types. Leaves are generally soft, are easily damaged by hail and wilt soon after picking. They are amongst the prettiest lettuces for potager use; the red-leaved varieties make dainty pinnacles at least 45cm/18in high if left to run to seed.

Red oak-leaved Salad Bowl type

Green oak-leaved Salad Bowl type

Stem lettuce This Asiatic lettuce, also known as ‘asparagus lettuce’ or ‘celtuce’, is grown primarily for its stem, which can be 21/2–71/2cm/1–3in thick and at least 30cm/12in long. Its leaves are coarse and palatable only when young, unless cooked. Cultivate it like summer lettuce, spacing plants 30cm/12in apart each way. It is tolerant of both low and high temperatures, but needs fertile soil and plenty of moisture to develop well. The stem is sliced and used raw in salads, but can also be cooked. It has a distinct lettuce flavour. Mature, firm-stemmed plants can be uprooted in autumn and transplanted into cold frames, with the leaves trimmed back. This enables them to be kept in good condition for a month or more.

Stem lettuce

–––––

Soil and site

Lettuces require an open situation, but in the height of summer and in hot climates can be grown in light shade. They can be intercropped between taller plants, provided they have adequate space and light. They do well in containers in fertile, moisture-retentive soil or compost.

–––––

Cultivation

Lettuce can be sown in situ, ‘indoors’ in seed trays or modules for transplanting, or in an outdoor seedbed for transplanting (see Plant raising).

Sowing in situ

• for seedling cut-and-come-again crops and leaf lettuce (see here);

• in very hot weather, when transplanted seedlings wilt badly after planting, unless raised in modules; for some overwintered sowings.

The disadvantage of sowing in situ is that germination and early growth are erratic if soil and weather conditions deteriorate, and, seedling and leaf lettuce crops apart, for good results thinning is essential.

Start thinning as early as possible – and use the thinnings in salads. Final spacing depends on the variety: small varieties like ‘Little Gem’ 12–15cm/5–6in apart; cabbage lettuces 23–30cm/9–12in apart; cos and ‘Iceberg’ types about 35cm/14in apart.

Sowing in modules (preferably) or seed trays for transplanting a reliable method of producing good-quality plants, which suffer minimal setback when planted out. It also allows for flexibility over planting.

Transplant young plants outside when conditions are suitable, or under the cover of cloches, frames, greenhouses or polytunnels. Lettuces are best transplanted at the four-to-five-leaf stage. Plant most types shallowly with the lowest leaves just above soil level, though cos lettuces can be planted a little deeper. I recommend planting at equidistant spacing, rather than in rows.

Sowing in an outdoor seedbed (Only advisable where there are no facilities for raising plants indoors, or no ground is available for direct sowing.)

Lettuce germinates at surprisingly low temperatures – it even germinates on ice – but some of the butterheads, and my favourite ‘Little Gem’, have ‘high-temperature dormancy’, which means that they germinate poorly at soil temperatures above 25°C/77°F. These temperatures frequently occur in late spring and summer. You can take various measures to overcome the problem, of which the main options are:

• Use crisphead varieties, which germinate at soil temperatures of up to 29°C/84°F.

• Sow between two and four in the afternoon. The most critical germination phase then coincides with cooler night temperatures.

• Put seeds somewhere cold to germinate, such as in a cold room, in a cellar or in the shade. Or cover seed trays with moist newspaper to keep the temperature down until germination.

• If sowing outdoors, water the seedbed beforehand to cool the soil; or cover it with white reflective film after sowing and remove it as soon as the seeds germinate.

–––––

Watering

Common lettuce problems, such as bitterness, bolting and disease, are exacerbated by slow growth, often caused by water shortage. In the absence of rain, water summer crops at the rate of up to 18 litres per sq. m/4 gallons per sq. yd per week. If watering regularly is difficult, concentrate on one really heavy watering about seven to ten days before harvesting. Water autumn-planted lettuce well when planting, but subsequently water sparingly during the winter months as damp leaves invite disease. Lettuce responds well to being mulched with organic material or polythene film.

–––––

Sowing programme

For a continuous supply of lettuce, make several sowings during the year, using appropriate varieties for each season.

Summer supplies For the earliest outdoor summer lettuce, sow under cover in early spring, transplanting outside as soon as soil conditions are suitable. These early crops can be protected initially with some kind of cloche or low polythene tunnel. Continue sowing in spring and early summer by any of the methods described above.

A problem in maintaining a steady summer supply of hearting lettuce is that growth rates vary during the season, from six and a half weeks to as much as thirteen weeks. Relevant factors include the variety, speed of germination, and soil and air temperature. In hot weather some varieties run to seed soon after maturing. In other words, regular sowing at ten- to fourteen-day intervals, as is often advocated, does not guarantee a steady supply.

Later sowings may overtake earlier sowings, leading to gluts and gaps. The best way to iron out fluctuations is to make the ‘next’ sowing when the seedlings from the last sowing have just emerged. The Salad Bowl types of lettuce stand well for several months. One or two sowings normally ensure a supply throughout the summer.

Autumn supplies Sow from mid- to late summer, using any of the methods shown here. In areas where autumn is normally wet, grow mildew-resistant varieties. If the weather deteriorates in autumn, cover outdoor lettuces with cloches or low polytunnels to keep them in good condition. These sowings can also be transplanted into frames, polytunnels or greenhouses if space is available.

Winter supplies Sow winter-hearting varieties in seed trays or modules in late summer and early autumn, transplanting into frames, greenhouses or polytunnels in late autumn. Successful cropping depends to some extent on the weather: in poor winters plants may not mature until spring. They will, of course, crop earlier if grown in gently heated conditions with a minimum night temperature of 2°C/36°F and day temperature of 41/2°C/40°F. Winter and early spring lettuce are very vulnerable to fungal diseases such as grey mould and downy mildew (see here). Avoid overcrowding and keep them well ventilated.

Spring supplies The earliest spring lettuce comes from crops grown in unheated greenhouses and polytunnels during winter. Use only varieties specifically bred for this period. Sow in autumn in seed trays or modules (each variety has a recommended sowing time), transplanting under cover. In slightly heated greenhouses, continue sowing in mid-winter/early spring for follow-on crops under cover.

The earliest outdoor spring lettuce comes from hardy varieties (capable of surviving several degrees of frost) that have been overwintered in the open. Sow in situ outdoors in late summer/early autumn, thinning initially to about 71/2cm/3in apart, and to the final spacing the following spring. Plants will be of better quality, and more likely to survive in good condition, if protected from the elements under cloches or low polytunnels or in frames.

Alternatively, you can sow the same hardy varieties or plant them under cover in late summer/early autumn, and thin in the same way. You can also sow them in seed trays or modules in late autumn, overwinter them as seedlings under cover, and plant in spring in the open or under cover.

There is always an element of chance with overwintered lettuce because of the vagaries of winter weather. It is worth the gamble if you yearn for early lettuce.

–––––

Seedling crops

Several varieties of lettuce are suitable for use at the seedling or baby leaf stage. In the past, seedling lettuce was commonly sown in heated frames in winter, providing out-of-season salading. The technique is still useful for early sowings under cover, as seedlings will be ready far sooner than hearting lettuce sown at the same time. You can make sowings throughout the growing season, a patch often providing two or occasionally three cuttings over several months. Seedling lettuce lends itself to intercropping and making decorative patterns. Besides the traditional ‘cutting’ lettuce varieties, it is worth experimenting with others, perhaps utilizing left-over seed. Only a few varieties prove bitter at the seedling stage. Lettuce is also a key ingredient in the many salad mixtures now widely available for sowing.

–––––

Leaf lettuce

This concept, based on the old seedling lettuce techniques, was developed in the 1970s at the vegetable reseach station which later became Horticulture Research International at Wellesbourne in the UK. The aim was to produce a crop of single leaves, to save caterers from having to tear apart the heart of a lettuce. The researchers discovered that if certain varieties of cos lettuce were sown closely, they grew upright without forming hearts, and regrew after the first cut, allowing a second crop within three to seven weeks. The method is easily adapted for use in the salad garden. A family of four could be kept in lettuce all summer by cultivating approximately 5 sq. m/6 sq. yd, and making ten sowings, each of about 80 sq. cm/1 sq. yd, cutting each crop twice.

The soil must be fertile and weed-free. Prepare the seedbed carefully to encourage good germination. Either broadcast the seed, thinning seedlings later to about 5cm/2in apart, or sow thinly in rows about 12cm/5in apart, thinning to about 3cm/11/4in apart. Plants must have plenty of moisture throughout growth.

Starting in spring, make the first seven sowings at weekly intervals. Make the first cuts in each case about seven weeks later, and a second cut a further six to seven weeks after that, during the summer. Make the last three sowings at weekly intervals in summer. These mature more rapidly, allowing the first cut after about three weeks (just overlapping with the tail end of the early sowings) and the second cut four weeks or so after the first. This gives continual cropping into autumn. Cut the leaves when 71/2–12cm/3–5in high, about 2cm/3/4in above ground level.

–––––

Varieties

A huge choice. These are old favourites and highly recommended newer varieties.

Cos lettuce ‘Chatsworth’, ‘Cosmos’, ‘Density’ syn. ‘Winter Density’ (hardy), ‘Frisco’, ‘Lobjoits Green Cos’, ‘Musena’, ‘Parris Island’, ‘Pinokkio’, ‘Romany’, ‘Rouge d’Hiver’ (hardy), ‘Tan Tan’ syn. ‘Tin Tin’

‘Winter Density’ cos

‘Rouge d’Hiver’ cos type

Semi cos (Little Gem type) ‘Atttico’ (good mildew resistance), ‘Little Gem’, ‘Little Gem Delight’, ‘Maureen’ Red varieties: see decorative below

‘Little Gem’ semi-cos

Butterhead ‘Arctic King’ (hardy), ‘Clarion’, ‘Tom Thumb’, ‘Marvel of Four Seasons’, ‘Valdor’ (hardy)

‘Marvel of Four Seasons’ semi-hearting

Bronze-leaved butterhead

Crisphead ‘Challenge’, ‘Hollywood’, ‘Robinson’, ‘Valmaine’ (hardy, good mildew resistance)

Crisphead type

Loose-leaf ‘Catalogna’, ‘Lettony’, ‘Lollo’ (green and red), Salad Bowl/Oakleaf types, ‘Veredes’

Green Lollo loose-leaf type

Red Lollo loose-leaf type

For seedling/babyleaf lettuce Salad Bowl varieties, smooth and curly-leaved cutting lettuce, most cos and semi-cos varieties, crisphead/‘Minigreen’

For leaf lettuce ‘Lobjoits Green Cos’, ‘Paris White Cos’, ‘Valmaine’

Shortlist for flavour all cos and semi-cos varieties, including ‘Little Gem’, ‘Pinokkio’, ‘Sherwood’

Red Batavian: ‘Red Batavian’, ‘Exbury’, ‘Relay’, ‘Rouge Grenobloise’

Green Batavian: ‘Blonde de Paris’, ‘Regina Ghiacci’/‘Queen of the Ice’

Red iceberg: ‘Sioux’

Loose-leaf: ‘Cocarde’ (red), ‘Catalogna’ (also suitable baby leaves)

Shortlist for decorative quality Red or red tinted os: ‘Amaze’, ‘Cosmic’, ‘Nymans’, ’Dunrobin’, ‘Little Leprechaun’, ‘Pandero’, ‘Rosemoor’

Loose-leaf: ‘Cocarde’ (green, red tinged), ‘Freckles’ (green, red splashed)

Red: ‘Lollo Rosso’, ‘Mascara’, ‘Navara’ (red, good mildew resistance), ‘Revolution’, ‘Frillice’, ‘Red Parella’ (hardy rosette)

–––––

Pests

These are the most common pests on lettuce. For protective measures and control, see here.

Birds Seedlings and young plants are most vulnerable, though mature plants are attacked from time to time.

Slugs Slugs can cause serious damage at every stage, especially in wet weather and on heavy soils. Red-leaved varieties seem less prone to slug damage.

Soil pests Wireworm, cutworm and leatherjackets all destroy plants, and are most damaging in spring.

Root aphids Colonies of yellowish brown aphids attack the roots, secreting a waxy powder. Plants grow poorly, wilt and may die. There are no organic controls: practise rotation and check current catalogues for varieties with a measure of resistance.

Leaf aphids (Greenfly) Attacks are most likely outdoors in hot weather and under cover in spring.

–––––

Diseases

There are no organic remedies for diseases, so prevention is all-important. Watch in current seed catalogues for new varieties with disease resistance or some degree of tolerance.

(As resistance eventually breaks down, resistant varieties tend to come and go.)

Damping-off diseases Seedlings either fail to emerge or keel over and die shortly afterwards. Avoid sowing in cold or wet conditions; sow thinly to avoid overcrowding; keep indoor crops well ventilated.

Downy mildew (Bremia lactuca) Probably the most serious lettuce disease, occurring in damp weather, mainly from autumn to early spring. Pale angular patches appear on older leaves and white spores on the underside. Leaves eventually turn brown and die. Avoid overcrowding; keep foliage dry by watering the soil rather than the plants; avoid watering in the evening; keep greenhouses well ventilated. Cut off infected leaves with a sharp knife. Burn them and debris from infected plants, which harbour disease spores. Use resistant varieties. Transplanted crops are less susceptible to mildew than direct-sown crops.

Grey mould (Botrytis cinerea) A rotting disease which commonly manifests itself at the base of the stem, causing plants to rot off. It is most serious in cold, damp conditions. Avoid overcrowding and deep planting; take preventive measures as above for downy mildew. Currently there are no varieties with effective resistance.

Mosaic virus A seed-borne disease causing stunted growth and yellowish mottling on the leaves, which become pale. Burn infected plants; try to control aphids, which spread the disease; use seed with guaranteed low levels of mosaic infection (less than 1 per cent); grow resistant varieties.

Chicory

Cichorium intybus

The chicories are a wonderfully diverse group of plants with a long history of cultivation for human, animal and medicinal use. The classical Roman writers often referred to the use of chicory as both a cooked and salad vegetable, and Italy is still the hub of the chicory world. The Italians grow an enormous range of chicories, some scarcely known further afield. ‘Radicchio’, a popular Italian name for chicory, has become widely identified with the red-hearted chicory. These red chicories have been embraced by the restaurant trade and have become a key ingredient in supermarket salad packs.

For the gardener, chicories have many merits. They are naturally robust, are mostly easily grown and have few pests, though the red chicories are prone to rotting diseases in autumn. Their main season is from late summer to spring, when salad material is scarcest, and they can often be sown or planted after summer crops are cleared, utilizing ground that would otherwise be idle in winter, both in the open and under cover.

Their acceptance in the English-speaking gardening world has been slow with the result that varieties available to home gardeners are more limited, even today, than they should be. If you become an aficionado, as I am, look to Italian, French and Belgian seed sources for a bigger choice.

–––––

Types of chicory

There are several distinct kinds of chicory. While the majority are grown for their leaves, some are cultivated for their roots and shoots.

The most striking of the leaf types are the red-leaved Italian chicories. Of the green-leaved chicories, the most widely grown is the Sugar Loaf type, used at the seedling stage, or when the crisp ‘loaf-like’ head has developed. Among other forms of leaf chicory are the rosette-shaped, extraordinarily hardy Grumolo chicory, and various wild, narrow-leaved chicories, not unlike dandelion. The Catalogna chicories, grown mainly for their spring shoots, are another distinct group.

Best known of the root chicories is Witloof (or Belgian) chicory. The roots are forced in the dark to produce white, bud-like ‘chicons’. Other root chicories are used raw in salads, much like winter radishes, while a few varieties were traditionally dried and ground as a coffee substitute. The beautiful pale blue chicory flowers can be used in salads, fresh or pickled.

Chicories have a characteristic flavour, with a slightly bitter edge – addictive to those who acquire the taste, but less popular with the sweet-toothed. The bitterness can be modified by shredding the leaves, washing them gently in warm water, by mixing them with milder plants and, where appropriate, by blanching the growing plants. Chicories can also be cooked, typically by braising, acquiring an intriguing flavour in the process. Bitterness varies with the variety and the stage of growth. Seedling leaves are less bitter than mature leaves, the inner leaves of Sugar Loaf chicories less bitter than the outer, and the red chicories become sweeter in cold weather.

–––––

Cultivation

Chicories are deep-rooting, unfussy plants. They adapt to a wide range of soils, from light sands to heavy clay, and even to wet, dry and exposed situations. They tolerate light shade. Although most are naturally perennial, for salad purposes it is best to treat them as annuals, resowing every year. Plants left to flower in spring will sometimes seed themselves but, because they cross-pollinate, resulting seedlings may not be true to type. In recent years plant breeders have improved the traditional varieties of red chicory beyond recognition. Unfortunately the high cost of this seed means that retail seedsmen supply only a limited choice. Mixtures of hardy chicories, sometimes sold as ‘Miscuglio’, make colourful seedling patches. Treat them initially as cut-and-come-again seedling patches, then allow a few plants to mature.

–––––

Red-leaved chicories

The outstanding feature of the so-called red chicories is their colour, which ranges from deep red and pinks to variegated leaves with flashes of red, yellow and cream on a green background. The old varieties were predominantly green in the early stages, but, chameleon-like, became redder and deeper-coloured with the onset of cold autumn nights. At the same time the leaves turned inwards, developing a nugget of sweeter, crisp, attractive leaves. The degree of hearting and colouring was always a lottery. Improved modern varieties develop earlier, more consistently, and are deeper-coloured. Varieties differ in their hardiness, from those that tolerate light frost, to ‘Treviso’, a unique loose-headed, non-hearting variety of upright leaves which, in our garden, has survived temperatures of -15°C/ 5°F.

In my experience the best hearting chicories are obtained by sowing in modules and transplanting. Red chicory can also be sown outdoors in rows, or in the traditional method of broadcasting, then thinning plants in stages to about 25cm/10in apart. In practice broadcast patches seem to ‘thin themselves’ by a kind of survival of the fittest. Varieties of the ‘Treviso’ type respond well to broadcasting.

Germination, particularly outdoors, can be erratic in hot weather, so take appropriate measures (see here). Chicory is sometimes trimmed back on transplanting to 71/2–10cm/3–4in above ground to stimulate growth, especially in hot weather. Space plants 25–35cm/10–14in apart, depending on variety.

Traditional red-leaved chicory showing root

Blanched red ‘Treviso’ chicory

Hearted red chicory ‘Red Verona’

Traditional variegated red chicory ‘Sottomarina’

Typical improved hybrid chicory

For summer supplies Sow from mid- to late spring using suitable early varieties, or plants may bolt prematurely. Protect plants with perforated film or fleece in the early stages. (Be guided by information on the seed packet on suitability for early sowing.)

For autumn/early winter supplies Sow from early to mid-summer. The hardier varieties will survive mild winters outdoors.

For winter/early spring supplies Sow under cover from mid- to late summer. Transplant under cover, or cover the plants in situ, in late summer/early autumn. Do not overcrowd this useful crop.

For cut-and-come-again seedlings Sow patches from late spring to mid-summer, extending the season with slightly earlier and slightly later sowings under cover.

Harvesting With successive sowings you can have hearted chicories from late summer until the following spring. Either pick individual leaves as required, or cut the heads about 21/2cm/1in or so above ground level, leaving the lowest leaves intact. The stumps normally produce further flushes of leaf over many weeks.

With cut-and-come-again seedling patches, start cutting when leaves are 5–71/2cm/2–3in high. Some will be tender at this stage; others may be bitter, depending on variety and the weather. You can later thin the seedlings, allowing a few to grow to maturity.

Winter protection The challenge with hearted chicories is to keep plants in good condition from late autumn into winter. In humid conditions they have a tendency to rot, usually starting with the outer leaves of the hearts. (Remove them carefully and you may find perfectly healthy hearts beneath.) Outdoor crops often keep well if protected with a light covering of straw, bracken or dry leaves – although there is a risk of attracting mice and even rats in severe winters. Glass cloches or low polytunnels can give additional protection, though polytunnels may encourage high humidity. We have harvested beautiful plants from under the snow: it can be a good insulator.

In unheated greenhouses and polytunnels, make sure there is good ventilation, and remove rotting leaves to limit the spread of infection. Keep plants reasonably well watered, or they may suffer from tipburn at the leaf edges. In spite of this, we have had some of our best hearted chicories from our polytunnel.

Forcing and blanching Certain varieties of red chicory, such as ‘Red Verona’ and ‘Treviso’, can be lifted and forced in the dark like Witloof chicory (see here). They can also be blanched in situ by covering with an upturned pot with light excluded. Cut back hearted varieties such as ‘Red Verona’ to within 21/2cm/1in of the stump, so that it is new growth that is blanched. You can force ‘Treviso’ this way, or alternatively blanch it more quickly by simply tying the leaves together before covering the plant. Blanched red chicories are exceptionally beautiful, the whitened leaves overlaid with pink hues. Blanching also makes them sweeter.

Varieties Improved varieties: ‘Cesare’ (suitable for early sowings), ‘Indigo’ F1 (unfortunately few other improved varieties are currently available to home gardeners)

Traditional varieties: ‘Palla Rossa Bella’, ‘Rossa Verona’ (Verona type), ‘Castelfranco’, ‘Sottomarina’ (variegated) Treviso types: ‘Treviso’ syn. ‘Rosso di Treviso’

–––––

Green-leaved chicories

Sugar Loaf chicory

A mature Sugar Loaf chicory forms a large, light green, tightly folded conical head, not unlike cos lettuce in appearance. The inner leaves are partially blanched by the outer leaves, and are pale, crisp, distinctly flavoured and sweeter than most chicories – though the ‘sweetness’ is only relative. They are naturally vigorous, responding well to cut-and-come-again treatment at every stage: seedlings, semi-mature and mature. Most varieties tolerate only light frost in the open, but if grown under cover in winter and kept trimmed back, are likely to survive winter well, giving regular pickings and resprouting vigorously in spring. They require fertile, moisture-retentive soil, but seem to have better drought resistance than comparable salad plants, such as lettuce, possibly because of their long roots.

Sugar loaf seedling

Mature Sugar Loaf chicory

For a hearted crop Sow by any of the methods used for red-leaved chicory (shown here). You can obtain good results by sowing in modules and transplanting, or by sowing in situ. Space or thin plants to 15–30cm/6–12in apart, the closer spacing for the older, less vigorous varieties.

For summer supplies Sow in spring/early summer. (A few varieties are unsuited to early sowing: be guided by information on the seed packet.)

For autumn supplies Sow in early/mid-summer; transplant later sowings under cover for winter crops, or cover in situ. Again and again I have found this to be an invaluable crop, in some years providing robust, refreshing, salad well into winter.

For winter or early spring supplies Sow in late summer and transplant under cover. This crop is a gamble as tight heads may not form until the following spring. However, loose leaves can generally be cut during the winter. Like the red chicories, Sugar Loaf heads are prone to rot in damp winter weather. Keep plants well ventilated and remove rotting leaves, but leave the stumps: even ‘hopeless cases’ may regenerate in spring. Traditionally, Sugar Loaf plants were uprooted in early winter and stored for several weeks, in closely packed heaps covered with straw in cellars or frames.

Cut-and-come-again seedlings Some older varieties of Sugar Loaf chicory are primarily used for cut-and-come-again crops. Sow from late winter/early spring through to early autumn, making the earliest and latest sowings under cover. These protected sowings are exceptionally good value. The first sowing under cover can be made as soon as soil temperatures rise above 5°C/41°F in spring. The late autumn seedling sowings under cover survive lower temperatures than mature plants, and start into renewed growth very early in the year.

Make the main sowings in succession throughout the summer for a continuous supply of fresh young leaves. They are best cut when 5–71/2cm/2–3in high; older leaves may be coarse. Growth is rapid, sometimes allowing a second cut within fifteen days of the first. A patch can remain productive over many weeks, provided the soil is fertile and there is plenty of moisture. Supplementary feeding with a liquid fertilizer will help sustain growth towards the end of the season. Cut-and-come-again seedlings can eventually be thinned to about 15cm/6in apart and left to develop small heads.

Varieties Traditional varieties, mainly recommended for cut-and-come-again seedlings: ‘Bianca di Milano’, ‘Bionda di Triestino’, ‘Imero – Dolce Greco’ Heading varieties: ‘Jupiter’ F1, ‘Uranus’ F1 As with the red-leaved chicories, the improved varieties are rarely available to home gardeners, probably on grounds of cost. If this changes, make use of them.

Grumolo chicory

This rugged little chicory from the Italian Piedmont survives the roughest winter weather to produce a ground-hugging rosette of smooth, rounded, jade-green leaves in spring. The leaves are upright during the summer months, but acquire a rosette form in mid-winter. They appear to die back in the depth of winter, but reappear remarkably early – green rosebuds at ground level! They tolerate poor soil, weedy conditions and low temperatures. They are naturally rather bitter, but you can blend them into mixed salads – they earn a place on the shape and colour of their leaves alone. The more mature leaves are coarser, but can be shredded or used cooked. Light and dark green forms are available.

Grumolo chicory

Cultivation While Grumolo chicory can be sown from spring to autumn, the most useful sowings are in mid-summer, for autumn-to-spring supplies. Grumolo chicory lends itself to being broadcast thinly in patches but can be sown thinly in rows 15cm/6in apart. In hot climates mid-summer sowings can be made in light shade. During the summer cut the young leaves when 5–30cm/2–12in high, but in autumn leave them to form rosettes. Patches will not normally need thinning unless they have been sown too thickly, in which case thin to about 71/2cm/3in apart.

In spring, or when the chicory is freshly sown, it may be necessary to protect from birds. Cloche protection in early spring will bring plants on earlier and make the leaves more tender. Cut the rosettes in spring, leaving the plants to resprout. The subsequent growth is never as prettily shaped and tends to become coarse, but may fill a gap in spring salad supplies.

Leave a few plants to run to seed – they form spectacular clumps 2m/7ft high, covered in pale blue flowers that tend to fade at noon. Pick these in the morning for use in salads. You can grow Grumolo chicory as a perennial by sowing a patch in an out-of-the-way place and letting it perpetuate itself.

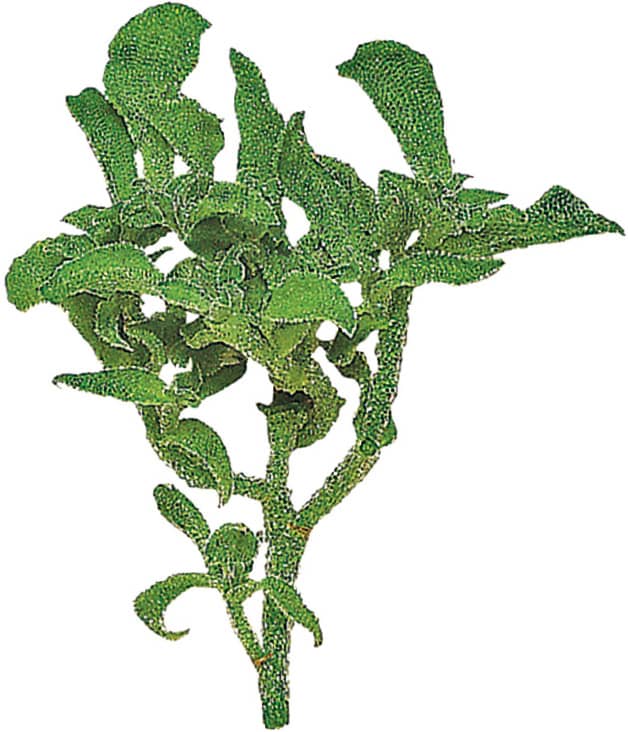

Catalogna chicory

Also known as ‘asparagus chicory’, this tall chicory from south Italy has long, narrow leaves, which can be smooth-edged or serrated with green or cream stalks. The ‘puntarelle’ types are grown primarily for the chunky buds (puntarelle) and flowering stems that develop in spring; they are bitter raw, but delicious cooked and cold in salads. The young leaves can be used in salads. Other types (such as Catalogna frastagliata) are grown for the leaves, picked either small, or as a bunch when 20–40cm/8–16in tall. ‘Red Rib’ and ‘Italico’ are forms with attractive, dark red veins. They are naturally very bitter and for this reason are sometimes blanched.

The Catalogna chicories are reasonably heat tolerant but stand only light frost. They are undemanding about soil. Sow leaf types in situ in summer, as cut-and-come-again seedlings or thinning to 15cm/6in apart. Sow puntarelle types in situ or in modules and transplant, spacing plants about 20cm/8in apart. In temperate climates they can be planted under cover in late summer, and will form shoots the following spring. Catalogna chicories make beautiful flowering clumps in their second season.

Wild chicory

Capucin’s beard or barbe de Capucin is the popular name for the jagged-leaved wild chicories. The young leaves can be eaten green (generally shredded), but blanching mature plants develops their unique flavour. Like many bitter and blanched plants, wild chicory is excellent aux lardons (see here). Sow from late spring to early summer in situ, thinning plants to about 15cm/6in apart. Blanch in situ or transplant under cover (see here). The top of the root is edible and well flavoured.

Wild chicory

–––––

Root chicories

Witloof chicory

Also known as Belgian chicory, this chicory was allegedly ‘discovered’ when a Belgian farmer threw some wild chicory roots into a warm dark stable. The whitened shoots which developed laid the foundations for the modern Witloof industry. Witloof chicory is easy to grow, tolerating a wide range of conditions. Avoid freshly manured ground, as it can result in lush plants and fanged roots. Improved modern varieties produce excellent, plump chicons.

Forced Witloof chicon

Root chicory

Witloof chicory root before forcing

Cultivation Sow in early summer, in drills 30cm/12in apart, or in modules for transplanting. Thin or space plants to about 23cm/9in apart. No further attention is required, other than keeping plants weed-free and watering in very dry weather.

Forcing Roots can be forced in situ or transplanted indoors. The latter is more convenient, but roots forced outside are said to be better flavoured. For forcing in situ, see here. To force indoors, dig up the roots in late autumn/early winter, and leave them exposed to light frost or low temperatures for a week or so. In theory fanged or very thin roots should be rejected (they should be at least 4cm/11/2in thick at the neck), but in practice even poor roots produce chicons of a sort. Cut back the foliage to 21/2cm/1in above the neck, and trim the roots to about 20cm/8in. For a continuous supply, force a few at a time, storing surplus roots in layers in boxes of moist sand, kept in a frostproof shed or cellar.

The simplest way to force roots is to pot several roots close together in a 23–30cm/9–12in flower pot, filled with soil or old potting compost. (This is to support the roots, not supply nutrients, as nourishment comes from the roots themselves.) Water gently, and cover the pot with an inverted pot of the same size with the drainage hole blocked to exclude light. (See illustration shown here.) Alternatively put the pot in total darkness. Keep the pot at a temperature of 10°C/50°F or a little higher. Inspect it from time to time, water if the soil has dried out and remove any rotting leaves. The chicons will normally be ready in about three weeks. Chicory can, of course, be forced in any darkened container large enough to take the roots.

Witloof chicory can also be transplanted into frames and greenhouses, using various means to create darkness (see here).

Once the chicons are ready, use them soon or they deteriorate. Cut them 21/2cm/1in above the root, and keep them wrapped in aluminium foil or in a refrigerator, as they become green and bitter on exposure to light. The root can be left in the dark to resprout: it will normally produce more leaf, but not a dense chicon.

Varieties ‘Apollo’, ‘Redoria’ F1, ‘Zoom’ F1

Other root chicories

Some chicories have large, edible roots, white and surprisingly tender – a useful winter standby. They are used raw, chopped or grated in salad, or cooked and eaten cold. Sow in spring or early summer by broadcasting, or sowing in rows or modules for transplanting, spacing plants eventually about 10cm/4in apart. The roots are moderately hardy and can be lifted during winter as required.

Varieties Few now listed by name

Heritage varieties: ‘Magdeburg’, ‘Geneva’, ‘Soncino’

Endive

Cichorium endivia

The endives are a versatile, attractive group of plants in the chicory family: indeed, in the non-English-speaking world they are known as ‘chicory’. They are a cool-season crop, growing best at temperatures of 10–20°C/50–68°F and tend to become bitter at higher temperatures. Don’t grow them in mid-summer where this is likely to be the case. All varieties survive light frost. Endives are more resistant to pests and disease than lettuce and, provided appropriate varieties are used, less likely to bolt in hot weather. They are also better adapted to the low light levels and dampness of autumn and winter. Their flavour is fresh and slightly piquant, but plants can be blanched before use, which makes the leaves milder, crisper and an attractive, creamy white colour. Many of the newer varieties are virtually self-blanching and naturally sweeter. Endive has become a popular ingredient in supermarket pre-packed salads.

–––––

Types of endive

Curly-leaved (frisée, staghorn, cut-leaved) These have a low-growing habit, and fairly narrow, curled, fringed or indented leaves, making a pretty head. They are more heat tolerant than broad-leaved endives, but more prone to rotting in damp and cold weather, making them the best varieties for summer use. They are among my potager favourites – neat and pretty: I often use them to outline vegetable patterns. They are also excellent as cut-and-come-again seedlings.

Blanched head of curly-leaved ‘Minerva’

Curly-leaved ‘Frisée de Ruffec’

Broad-leaved (Batavian, escarole, scarole) These are larger plants, with broader, smoother, somewhat furled leaves, which can be upright or low-growing and compact. They can withstand temperatures as low as -9°C/15°F, so are generally the best value for winter-to-spring crops. Mature plants respond well to cut-and-come-again treatment, making them among the most productive salads in winter under cover. Modern plant breeding is producing intermediate varieties, with some of the characteristics of each type.

Broad-leaved ‘Cornet de Bordeaux’

–––––

Cultivation

Endives like an open situation and fertile, moisture-retentive soil, with plenty of well-rotted organic matter worked in beforehand. Very acid soils should be limed.

Either sow in situ and subsequently thin out or transplant, or sow in modules for transplanting. Transplanted endive is said to grow faster and be less likely to become bitter. Seed germinates best at 20–22°C/68–72°F. Germination may be poor at higher soil temperatures, with slow-germinating plants being prone to premature bolting. (For sowing in hot conditions, see Lettuce.) Depending on variety, space plants 25–35cm/10–14in apart. On average endives take about thirteen weeks to mature. Use thinnings in salads or transplant to maintain continuity.

–––––

Sowing programme

Early summer supplies Sow under cover very early in spring, transplanting outdoors as soon as soil conditions allow. Protect with cloches or crop covers. These early sowings may bolt prematurely if temperatures fall below 5°C/41°F for several days.

Main summer supplies Sow in mid- to late spring.

Autumn supplies outdoors Sow in early to mid-summer. Use hardier varieties for the late sowings; in mild areas they may stand well into winter. Protect with cloches or crop covers if necessary.

Autumn and winter supplies under cover Sow in mid-summer to early autumn, transplanting under cover in autumn. With cut-and-come-again treatment, of the broad-leaved types in particular, it may be possible to make several cuts during winter.

Late spring supplies Sow hardy broad-leaved varieties in modules under cover in late autumn, overwintering them as seedlings and planting early in the year, under cover or outside.

Cut-and-come-again seedling crops Sow from late winter to early autumn. Make the earliest and latest sowings under cover, provided the soil temperature is above 15°C/59°F. Curly endive makes particularly appealing salad seedlings, though all types can be used. They lend themselves to intercropping and being sown in decorative patches.

–––––

Blanching

Whether or not you blanch endives before harvesting is largely a matter of taste. I find most of them quite palatable ‘as they are’, although there is something irresistible about the crisp, white centre of a blanched curly-leaved endive. For blanching techniques see here. In the main, endives are blanched in situ, using covering methods for compact, low-growing varieties and tying the heads of looser-leaved varieties. Curly-leaved endives benefit most from blanching in hot weather, when they tend to be more bitter. A simple, old-fashioned blanching method is to cover one endive with an uprooted one. Simply pull up one plant, then place it, with the head down and root in the air, on to the head of a growing plant. Mutual blanching results!

–––––

Varieties

Curled For spring and summer supplies:

Fine de Louviers

For autumn and winter supplies: ‘Minerva’ (Wallonne type), ‘Naomi’, ‘Pancalière’, ‘Ruffec’

Broad-leaved For supplies for any season: ‘Grosse Bouclée 2’

Hardiest: ‘Cornet de Bordeaux’, ‘Géant (Giant) Maraîchère’ race ‘Margot’ and race ‘Torino’, ‘Ronde Verte à Coeur Plein’ (‘Fullheart’)

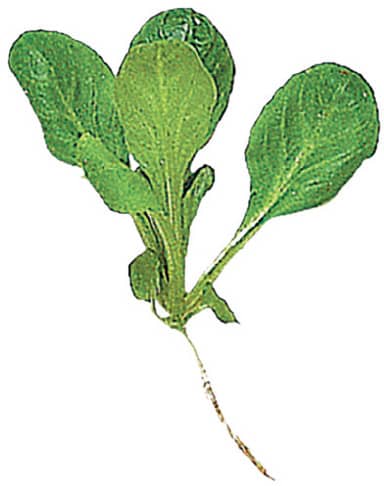

Spinach

Spinacia oleracea

My conventional English upbringing never led me to suspect that spinach could be a salad vegetable. It took a visit to the USA, where it has long been used in salads, for me to realize its merits and it has been a favourite ever since. To satisfy today’s huge demand for ‘baby leaf’ spinach in prepacked salads, plant breeders are continually introducing improved hybrid varieties, whose good disease resistance and upright habit make for healthy plants.

Spinach has a unique flavour – ‘spinachy’ is the only word to describe it. The most popular varieties are round-leaved, though some older varieties and Asiatic spinach are pointed. Texture varies from thin, smooth-leaved types to those with thicker, puckered leaves, which are more robust, less easily bruised and bulkier, so predominate in the salad packs found in supermarkets.

Mature spinach can be used in salads, though leaves may need to be torn or shredded to make them a manageable size. On the whole it makes far more sense, in terms of space, time and an end product that’s ‘just right’ for salads, to grow spinach as a cut-and-come-again, baby leaf crop.

–––––

Cultivation

Spinach is an annual, cool-season crop, with a natural tendency to run to seed in the lengthening days of late spring and early summer, and at high temperatures. It grows best in early spring and late summer. Mid-summer sowings of traditional varieties were often unproductive. The hardier varieties survive light to moderate frosts in the open, but will be of far better quality if grown under cover in winter. The secret of a year-round supply in temperate climates is to sow appropriate varieties for the season. See the sowing programme and be guided by seed packet and catalogue information.

Spinach needs fertile, well-drained, moisture-retentive soil that is rich in organic matter. Summer crops can be grown in light shade, provided there is adequate moisture. It is advisable to rotate spinach around the garden, as the resting spores of downy mildew, a scourge of spinach with no organic remedy, remain in the soil. However look out for newer varieties with reasonable mildew resistance.

On account of its tendency to run to seed rapidly, spinach is usually sown in situ, but it can be sown in modules and transplanted. For single plants sow in drills 27–30cm/11–12in apart, thinning to 15cm/6in apart. Depending on the season, these plants may respond well to cut-and-come-again treatment. For cut-and-come-again seedling crops, make successive sowings at roughly three-to-four-week intervals (but see the sowing programme). Bear in mind that very early sowings, or sowings in hot spells, run the risk of premature bolting. You can normally make the first cuts within thirty or forty days of sowing: two or three subsequent cuts are often possible. Seedlings can be thinned to 71/2–10cm/3–4in apart and grown as small plants.

–––––

Sowing programme

For summer supplies Sow from late spring to early summer, using slow-growing, long-day varieties with good bolting resistance. The following are among many recommended for baby leaf crops: ‘Emilia’, ‘Fiorano’ F1, ‘Medania’ F1, ‘Palco’, ‘Tetona’ F1, ‘Violin’ F1

For autumn, winter and early spring supplies Sow from mid- to late summer outside, and early to mid-autumn under cover. The late sowings may stop growing in mid-winter, but will start again in early spring. You can also sow under cover in early spring if soil conditions are suitable. For all these sowings, use faster-growing, short-day varieties such as ‘Giant Winter’ ‘Mikado’ F1 (Oriento), ‘Palco’, ‘Samish’ F1, ‘Triathlon’ F1, ‘Turaco’ F1

–––––

Swiss chard and Perpetual spinach Beta vulgaris var. cicla

Swiss chard (also known as seakale beet, silver chard and silver beet) and perpetual spinach (or spinach beet) are both considered ‘leaf beets’ as they technically belong to the beetroot family. In appearance, however, they are far more like spinach. Their leaves are coarser than spinach and less distinctly flavoured, and were traditionally grown for use cooked. However, the development of ‘baby leaves’ has seen Swiss chard soar in popularity due to the colourful stems and reddish tints in some leaves, while perpetual spinach is a useful cut-and-come-again crop.

Swiss chard

These vigorous biennial plants have large, thick, glossy leaves and prominent leaf ribs and stalks, in some varieties yellow, orange, pink, purple or red. They can be almost luminescent, making them superb ‘potager’ plants. Mature chards require cooking, and it is advisable to cook the stems a little longer than the leaves. Stems and leaves, when coloured, retain some colour after cooking so merit being mixed into salads cold. However, the raw baby leaves are best suited to salads.

Chard is more heat, cold, drought and disease-tolerant than spinach and is probably one of the easiest vegetables to grow. Although slower-growing than spinach, it can be grown for much of the year, cropping over many months.

For both large plants and cut-and come-again (baby leaf) seedlings, sow from spring to late summer outdoors, though very early outdoor sowings may bolt prematurely. For winter and spring supplies, sow in early autumn and early spring under cover. Seed catalogues list mixtures such as ‘Bright Lights’, as well as varieties with notable red, yellow, pink and silvery stems, and some with reddish leaves. ‘Fordhook Giant’ and ‘Lucullus’ are very productive, green-leaved, white-stemmed varieties.

‘Bright Lights’ Swiss chard

Perpetual spinach (spinach beet)

More like spinach than Swiss chard, perpetual spinach is very versatile and far less likely to run to seed than spinach. So it remains productive over a much longer period. In practice it often perpetuates itself by self-seeding or simply surviving from one year to the next, if picked regularly. Cultivate as Swiss chard above. Where growing spinach proves difficult, perpetual spinach is an excellent alternative.

Mild-flavoured leaves

These are easily grown, undemanding salad plants, with relatively mild flavours. Look on them as supplying the ‘gentle notes’ in a salad, softening the ‘discords’ of sharp flavours. They are listed here alphabetically according to their Latin names.

–––––

Leaf amaranth (calaloo, Chinese spinach) Amaranthus spp.

These highly nutritious, spinach-like plants are normally cooked, but the young leaves are surprisingly tasty in salads. Amaranths need a temperature of 20–25°C/68–77°F to flourish outdoors, and will not stand any frost. For salads, sow in situ from spring to summer, under cover or outside, provided the soil is above 20°C/68°F and there is no danger of frost. Grow it either as cut-and-come-again baby leaf, or space plants 10–15cm/4–6in apart and harvest the young leaves. The deep red and blotched red- and green-leaved varieties are very productive and the most colourful in salads, but the pale, so-called ‘white-leaved’ varieties have a tender, buttery flavour. Deep red varieties such as ‘Red Army’ and ‘Garnet Red’ are popular subjects for microgreens.

Leaf amaranth

–––––

Orache (mountain spinach) Atriplex hortensis

Orache is a handsome annual plant, growing up to 2m/7ft high. Green- and red-leaved forms are the most widely grown, sometimes available as mixtures. So-called ‘red’ strains range from muddy brown to pure scarlet, so if you have a nicely coloured one, save your own seed! Use only young orache leaves in salads; they have a faint spinach flavour and almost downy texture. Either pick leaves from young plants, or grow cut-and-come-again seedlings.

For larger plants, sow in situ in spring and early summer, thinning to 20cm/8in apart. Plants grow rapidly, so keep them bushy and tender by regularly picking the topmost tuft of leaves. Even so, they eventually ‘get away’ from you! Leave a few of the best to self-seed. Bountiful seedlings appear early the following year. Alternatively, to grow as cut-and-come-again seedlings, make continuous sowings from late spring under cover, followed by outdoor sowings until late summer, with a final sowing under cover in early autumn. Summer sowings may bolt prematurely, but late sowings under cover may remain in usable condition for much of the winter.

Red orache

–––––

Texsel (texel) greens Brassica carinata

This brassica was developed in the late twentieth century from an Ethiopian mustard. Its small glossy leaves have a distinct, clean flavour with a delightful hint of spinach in them. It is very nutritious and rich in vitamin C. It is reasonably hardy (plants have survived -7°C/20°F in my garden) and very fast-growing. For this reason it is often grown where clubroot disease is a problem: it can be harvested before becoming seriously infected. It is useful for intercropping. Texsel is appreciated as cooked greens in the Indian community, the plants being harvested when 25–30cm/10–12in high. At this stage the smaller leaves and young stems can be eaten raw in salads. Palatable leaves can even be picked from the flower stems. However, small seedling leaves are, in my view, the best-flavoured. This last spring it was my star performer. I had sown a tiny patch in my greenhouse in late winter, and was able to make frequent pickings of perky tasty leaves over two months, before it ran to seed. And now I’m saving the seed for another year.

In the USA Texsel is being sold under the name ‘amara’. To quote Jamie Chevalier, who writes the Bountiful Gardens seed catalogue, ‘l love the bitter almond and garlic overtones in its flavour, so much more complex than most brassicas.’ Incidentally a totally different use for Texsel is as game cover, sometimes grown up to 11/2m/5ft high!

Texsel may bolt prematurely in hot and dry conditions, and it grows best, and is best value, in the cooler, autumn-to-spring period. It is usually sown in situ. Make early cut-and-come-again seedling sowings under cover in late winter/early spring; continue sowing outdoors in late spring and early summer; avoid mid-summer sowings, but start sowing again outdoors in late summer/early autumn, with final sowings under cover in mid-autumn. You can sometimes make the first cut of seedling leaves within two to three weeks of sowing, with a second cut a few weeks later; occasionally these leaves are bitter.

Research has shown that small plants produce the highest yields when sown in rows 30cm/12in apart, thinned to 21/2cm/1in apart, or in rows 15cm/6in, thinned to 5cm/2in apart. In clubroot-infested soils, you can make successive sowings if you pull up plants by the roots when harvesting, leaving a three-week gap before the next sowing. Texsel is generally a healthy crop, but flea beetle (see here) may attack in the early stages. Growing under fine-mesh horticultural nets is a solution.

Texsel greens

–––––

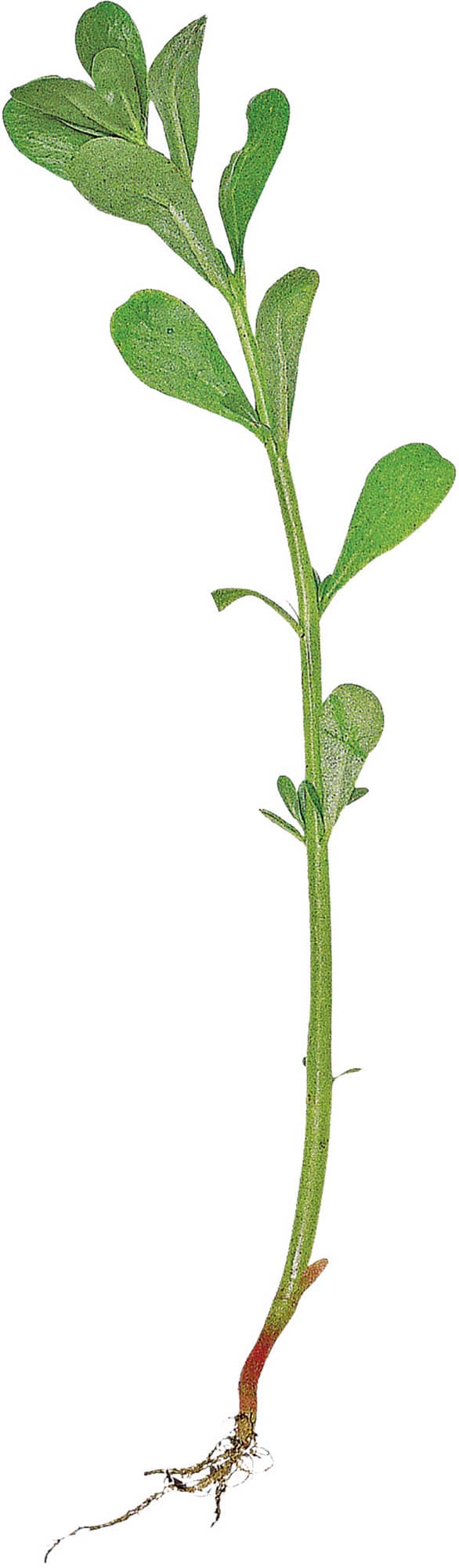

Salad rape Brassica napus

Salad rape is often used as a mustard substitute in ‘mustard and cress’ packs; it has a milder flavour than mustard with a hint of cabbage in it. It is a very useful garden cut-and-come-again seedling crop, being much slower to run to seed than mustard or cress. I have had spring-sown patches that remained productive for four months. Moreover it does not become unpleasantly hot when mature. It germinates at low temperatures and in my experience survives -10°C/14°F. Seed can be sprouted and grown in shallow containers.

In temperate climates, sow as cut-and-come-again seedlings outdoors throughout the growing season. For exceptionally useful winter-to-spring supplies, sow under cover in late autumn and early winter, and again in late winter and early spring. Cut-and-come-again seedlings may give three, even four successive cuts. If left uncut, salad rape grows to about 60cm/24in high. At this stage the small leaves on the stems are still tender enough to use in salads. It grows very fast, so if you want it with cress, sow it three days later. Salad rape has one failing: it is very attractive to slugs (for control, see here). I have even considered sowing strips as slug decoys!

Salad rape

–––––

Tree spinach Chenopodium giganateum ‘Magentaspreen’

This handsome relative of fat hen or lamb’s quarters (Chenopodium album) grows rapidly to at least 13/4m/6ft high. The tips of many leaves and the leaf undersides are a beautiful magenta pink, as are the flowering spikes. The leaves have a floury texture and a flavour reminiscent of raw peas. Only use young leaves in salads. Either grow it as cut-and-come-again seedlings, sowing throughout the growing season; or sow it in spring and early summer, in situ or in modules, spacing plants about 25cm/10in apart – in which case pick the young leaves for salads. It self-seeds prolifically, with abundant seedlings appearing early the following spring – ready for use in salads. It can become invasive, but it is a genial, easily uprooted invader, deserving a place (at the back) of any potager border.

–––––

Alfalfa (lucerne, purple medick) Medicago sativa

Alfalfa is a hardy semi-evergreen perennial in the clover family, with attractive blue and violet flowers. Mature plants can grow up to 90cm/36in high, becoming quite bushy. It is deep-rooting, so withstands dry conditions well. As both foliage and flowers are decorative, it is sometimes grown as a low hedge, dividing the garden into sections. The clover-like young leaves, which have a distinct, pleasant flavour, are used in salads. The seeds can be sprouted, and it is also grown as a green manure.

Grow it either as a perennial or as cut-and-come-again seedlings (you can use seed sold for sprouting). For perennial plants, sow in situ in spring or late summer to autumn, thinning to 25cm/10in apart, or alternatively sow in modules and transplant. Pick the young shoots for salads. Cut the plants back hard after flowering to renew their vigour. After three or four years, it is best to replace them or they become very straggly. For cut-and-come-again seedlings, sow in spring and early summer, and again in late summer and early autumn. For an extra tender crop, make the earliest and latest sowings under cover. You can make pickings throughout the growing season, but the leaf texture becomes tougher as the plants mature.

Alfalfa

–––––

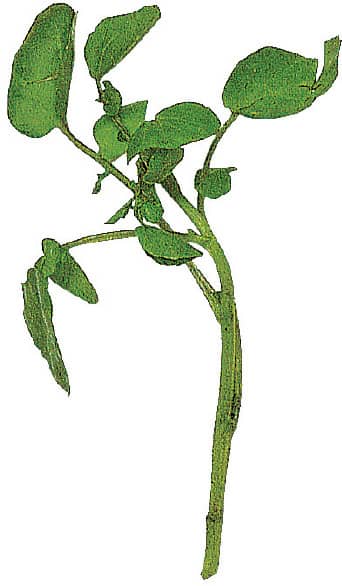

Winter purslane (claytonia) Montia perfoliata (syn. Claytonia perfoliata)

A native of North America, where it is known as miner’s lettuce and spring beauty, this dainty hardy annual is an invaluable spring salad plant. Its early leaves are heart-shaped, but the mature leaves, borne on longer stalks, are rounded and wrapped around the flower stem as if pierced by it. Leaves, young stems and the pretty white flowers are all edible. They are refreshingly succulent, if slightly bland, which may be why children seem to like them. Avoid the pink-flowered ‘pink purslane’ (Montia sibirica): its leaves have an acrid aftertaste.

Winter purslane flourishes in light, sandy soils but, provided drainage is good, adapts to most conditions, including quite poor, dry soils. It is reasonably hardy outdoors in well-drained soil, but its winter quality is vastly improved with protection. Grow it as a cut-and-come-again, baby leaf crop or – probably the most productive method – as single plants.

It can be grown for much of the year, but it is best value, and grows best, in late autumn and early spring. Crops under cover stop growing in mid-winter, but burst into renewed growth early in the year. The seeds are tiny, so sow shallowly, in situ or in modules for transplanting, spacing plants about 15cm/6in apart. For summer supplies, sow in early to late spring. For autumn and early-winter-to-spring supplies, sow in summer, planting the later sowings under cover, unless you are sowing in situ. Pick leaves from mature plants as required, or cut the whole head 21/2cm/1in above ground: it will resprout vigorously before eventually running to seed in late spring. Cut-and-come-again crops give at least two cuts.

Once established, winter purslane self-seeds prolifically, carpeting the ground with seedlings in autumn and spring. They are shallow-rooted, but can be carefully transplanted, perhaps under cover in autumn. If it becomes invasive, dig it in as a green manure in spring.

Winter purslane

–––––

Iceplant Mesembryanthemum crystallinum

Iceplant is an attractive, sprawling plant with thick, fleshy leaves and stems covered with tiny bladders that sparkle in the sun like crystals. It grows wild on South African and Mediterranean shores. In hot climates it is perennial, and is cultivated as a substitute for spinach in summer. I feel it is far better raw in salads – if only for its unusual appearance. Leaves and sliced stems have a crunchy succulence (not to everyone’s taste!) and an intriguing, albeit variable, salty flavour. It grows best in fertile soil, but tolerates poorer, but well-drained, soil.

Although it is a sun-lover, in mid-summer it can be grown undercropping sweet corn. It makes an attractive ground-cover plant in a potager, and, with its trailing habit, looks effective in pots or hanging baskets.

Iceplant is not frost hardy, so make the first sowings in modules or seed trays under cover and plant out, initially with protection if necessary, when all danger of frost is past. Space plants 30cm/12in apart, and protect against slugs in the early stages (see here). In warm climates, sow in situ outdoors in late spring or early summer. You can take stem cuttings in early summer (they root quite quickly) to provide a follow-on crop, which you can plant under cover in late summer.

You can normally pick individual leaves or small ‘branches’ of leaves and stems a month or so after planting. Keep picking regularly, to prevent plants from running to seed and getting coarse, and to encourage further shoots. Surprisingly, mature plants tolerate light frost and, if given protection, continue growing well into autumn, though the quality is slightly impaired.

Iceplant

–––––

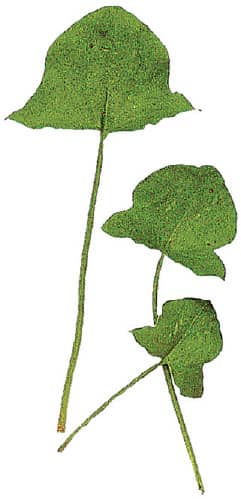

February orchid (Chinese violet cress) ‘shokassai’ (Japanese) Orychophragmus violaceus

Essentially an Asiatic weed, February orchid can be grown as an annual or biennial. It has light green leaves, which vary in shape from roundish to deeply serrated, and can be up to 71/2cm/3in in width. It is naturally vigorous, young plants in their leafy stage being 10–15cm/4–6in high but then shooting up to 45cm/18in or more when running to seed. This results in masses of beautiful, lilac flowers, not unlike the flowers of honesty (Lunaria annua). Their fresh brightness boosts my spirits every spring, their natural time for flowering, hence one of its (several) Chinese names, February orchid. The flowers are edible and decorative in salads. Evidently in the past Orychophragmus violaceus was cultivated as an ornamental in European flower borders and cool greenhouses.

The raw leaves have an interesting, mild flavour – my personal opinion, not everyone agrees. They can also be cooked like spinach or used in stir-fries. The great merit of this plant is its tolerance of low winter light levels. It flourishes when so many of our salad plants are in the doldrums, its mildness a good foil to the bitterness of endives and chicory.

The main problem is that there are few sources of seed. (See seed suppliers or ‘Google’ for new suppliers.) Once you have grown it however, you have it for life. It self-seeds readily, though is easily pulled up if showing signs of becoming invasive. It is very easy to save your own seed, the best way being to leave a few plants in spring, in a cold greenhouse or polytunnel, collecting the seed in early summer. It will also self-seed outdoors in areas with relatively mild winters.

February orchid is not fussy about soil provided drainage is good, and is reasonably hardy, overwintering outside if temperatures don’t fall below about -5°C/23°F. While the most useful sowings are in late summer to early autumn, for an autumn and spring crop to be grown under cover, it can be sown from early spring to early summer for an outdoor crop. Sow in situ or in modules for transplanting. It can be grown as a cut-and-come-again baby leaf crop, or thinned to 15cm/6in apart for larger plants. Leaves can be picked as they reach a reasonable size, even from the stems of seeding plants. If you want flowers, simply leave a few plants to run to seed.

–––––

Summer purslane Portulaca oleracea

Forms of purslane (not to be confused with winter purslane, which is a different plant) grow wild throughout the temperate world and have been cultivated for centuries. It is a low-growing, half-hardy plant with succulent, rounded leaves and slender but juicy stems. There are green and yellow forms. The green are more vigorous, thinner-leaved and, some say, better-flavoured; the yellow or ‘golden’ form has thicker, shinier leaves, and is more sprawling, but is very decorative in salads. The leaves and stems are edible raw and have a refreshing, crunchy texture but a rather bland flavour. In the past all parts were pickled for winter use. It is a pretty plant and a favourite in the summer potager; I love to make striped patterns with alternating rows of the two colours. They are productive for many weeks in summer, looking good throughout.

Purslane does best on light, sandy soil but succeeds on heavier soils if they are well drained. It grows profusely in warm climates, but in cooler conditions choose a sheltered, sunny site or grow it under cover.

It can be grown as single plants or, probably the more productive method, as cut-and-come-again baby leaves. As the seed is tiny, and the fragile young seedlings are prone to damping-off diseases (see here), you gain nothing by sowing before the soil has warmed up. For an early start, sow in a heated propagator in late spring, planting out after all danger of frost is past – under protection if necessary. Sow in situ outdoors from late spring (in warm areas) to mid-summer. Space plants 15cm/6in apart. For very useful early summer and late autumn cut-and-come-again seedling crops, sow under cover in mid-spring and late summer.

Cut-and-come-again baby leaves are normally ready within four or five weeks of sowing, and may give two or three further cuts. You can make the first pickings from single plants about two months after sowing. Pick individual leaves or stemmy shoots, always leaving two leaves at the base of the stem, where new shoots will develop. It is essential to pick regularly or plants run to seed, becoming coarse.

Remove any seed heads that develop: they are knobbly and unpleasant to eat. Keep plants well watered in summer. The gold-leaved forms are said to remain brighter if watered in full sun. Plants naturally decline in autumn, but may get a new lease of life if you cover them with cloches or fleece.

Yellow purslane

Green purslane

–––––

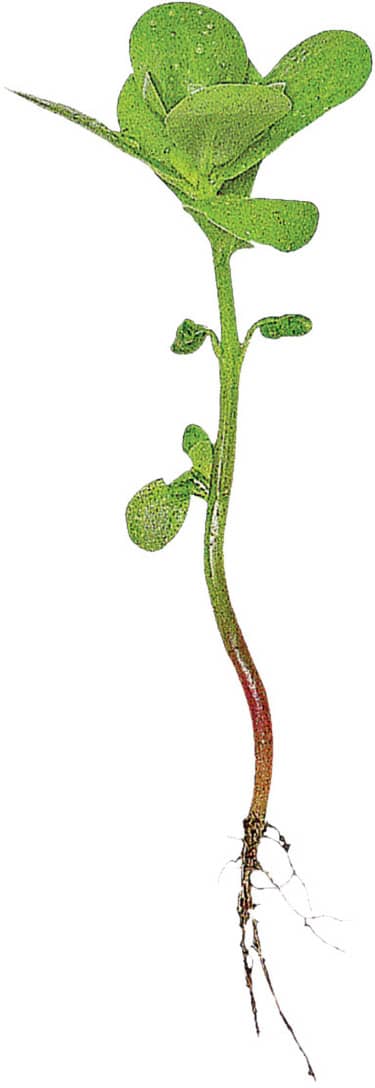

Corn salad (lamb’s lettuce, mâche) Valerianella locusta

This small-leaved hardy annual and closely related species are found wild in much of the northern hemisphere. Rarely more than 10cm/4in high, its fragile appearance belies its robust nature. Its gentle flavour and soft texture make it invaluable in winter salads, although it can be grown most of the year. The flowers are inconspicuous but edible. It is undemanding, tolerates light shade in summer and is ideally suited to intercropping. A traditional European practice was to broadcast corn salad seed on the onion bed prior to lifting the onions. The larger-seeded type has pale green, relatively large, floppy leaves, while the smaller-seeded types, known as verte or ‘green’, are darker, compact plants with smaller, crisper, upright leaves. They are reputedly hardier, and mainly used for late sowings.

While the traditional varieties still give reasonable results, improved selections and varieties are becoming available, which are more productive and versatile. Some are listed below.

Corn salad can be grown as cut-and-come-again seedlings or as individual plants, the latter probably being more productive. As plants are so small corn salad is normally sown in situ, although you can sow it in modules or seed trays and transplant, spacing plants 10cm/4in apart. It must be sown on firm soil, and may germinate poorly in hot, dry conditions. If so, take appropriate measures (see here).

For early and mid-summer supplies, start sowing under cover in late winter/early spring (the first cuttings will help fill the ‘vegetable gap’), continuing outdoors in mid- and late spring. For the main autumn/early winter supplies, sow from mid-summer to early autumn outdoors, making a final sowing in early winter under cover for top-quality winter plants. Although corn salad is very hardy, surviving at least -10°C/14°F, outdoor plants are always more productive if protected with, say, cloches or fleece.

Corn salad grows slowly, taking about three months to develop to maturity. Baby leaf seedlings are ready several weeks sooner. Pick individual leaves from the plants, or cut across the head to allow resprouting, or pull them up by the roots, as is done commercially – otherwise leaves wilt rapidly. Cut seedlings as soon as they are a useful size. They will resprout at least once. A patch can more or less perpetuate itself if you leave a few plants to self-seed.

‘Green’ corn salad

Varieties Large-leaved varieties: ‘Dutch’, ‘English’, ‘Pulsar’

‘Green’ varieties: ‘Baron’, ‘Favor’, ‘Verte de Louviers’, ‘Verte de Cambrai’, ‘Verte de Cambrai’ race ‘Cavallo’, ‘Verte de Louviers’, ‘Vit’

Large-leaved corn salad

Strong-flavoured leaves

Not all the strong-flavoured plants in this group are to everybody’s liking. But mixed into salads in small quantities, especially blended with mild-flavoured leaves, they can be the catalyst for wonderfully individual salads. The herb coriander (shown here) could be included here. They are listed here in alphabetical order by their Latin names.

–––––

Land cress (American, belle isle, upland or winter cress) Barbarea verna

A very hardy, low-growing biennial, land cress has dark green, shiny, deeply cut leaves that remain green all winter. Its strong flavour is almost indistinguishable from watercress, and it is used in the same way, cooked or raw in salads. It grows best in moist, humus-rich soils; in hot, dry soils it may run to seed prematurely unless kept well watered. You can grow it in light shade in summer, and intercrop it between taller vegetables.

It is at its best in the winter months, making a neat edging for winter beds. Although it is hardy to at least -10°C/14°F, the leaves will be far more tender to eat if you protect plants with, say, cloches. You can grow it as single plants, spaced 15cm/6in apart, or as cut-and-come-again seedlings. For sowing times and cultivation, see Corn salad. The first leaves are normally ready for use within about eight weeks of sowing and cut-and-come-again seedlings several weeks sooner. Young plants are susceptible to flea beetle attack; for control, see here. Land cress runs to seed in its second season. You can leave patches in out-of-the-way corners to perpetuate themselves. This sometimes seems the simplest way to grow it!

There is also a pretty variegated form of land cress, the green leaves dappled with white or pale yellow blotches. It seems to be less hardy, and slightly milder flavoured than standard land cress.

Land cress

–––––

Chrysanthemum greens (shungiku, garland chrysanthemum, chop suey greens) Chrysanthemum coronarium)

This annual chrysanthemum, grown as an ornamental, has indented or rounded leaves, depending on variety, and pretty, creamy yellow flowers. The nutritious leaves are used widely in oriental cookery, but with their strong, aromatic flavour should be used only sparingly in salads when raw. The Japanese plunge them into boiling water for a few seconds, then into cold water, before mixing them into salads.

The flower petals are edible, but discard the centre, which is bitter. Mature plants can grow over 60cm/24in high; for salads it is best grown as small plants or cut-and-come-again seedlings.

It thrives in moist, cool conditions, and you can grow it in light shade in summer. Being tolerant of low winter light and moderately hardy, it is best value in the leaner months, from autumn to spring. The leaves stand well in winter, especially under cover.

For cut-and-come-again baby leaves (it makes a pretty intercrop), start sowing under cover in early spring. Continue sowing outdoors as soon as the soil is workable. For an autumn to early spring supply, sow in late summer outdoors and in early autumn under cover, protecting outdoor sowings if necessary. You can usually cut seedlings four or five weeks after sowing; further cuts may be possible, but uproot plants once the leaves become tough. You can also sow chrysanthemum greens in seed trays or modules, spacing plants 15cm/6in apart. These will be ready eight to ten weeks after sowing. Pick frequently to encourage further, tender growth, and remove flowering shoots. Bushy plants usually regenerate if cut back hard. Give them a liquid feed to stimulate growth. Plants left to flower may self-seed. Use improved named varieties where available.

Chrysanthemum greens

–––––

Rocket (arugula) Eruca vesicaria subsp. sativa and wild rocket (sylvetta) Diplotaxis tenuifolia

There has been an explosion of interest in rocket in the last decade, driven by chefs looking for interesting, spicy leaves to add to salads. Of Mediterranean origin, in the past the annual rocket was far and away the most widely grown type. It has gently indented or straight leaves, creamy white (edible) flowers and a moderately spicy flavour. The perennial wild rocket has far more deeply indented, darker leaves, yellow flowers and a fiery flavour. Plant breeders have now developed improved varieties of both types – wild rocket now including varieties of wild rocket with ferocious heat, and others with striking, red-veined leaves. Some of the old distinctions of leaf form have been eroded in the process, so there are annual rocket varieties with deeply indented leaves and wild rocket varieties with broader leaves. It’s a changed scene, but for everyday use in salads, I still prefer the classic ‘old fashioned’ type to the more exotic wild rockets. Use these very sparingly when you’re looking for an extra kick!

Rocket is a small but fast-growing plant. It can stand several degrees of frost, and undoubtedly grows best in cool weather. Plants run to seed very rapidly in hot, dry conditions, or if stressed in any way – by lack of water, poor soil or overcrowding for example – in which case the leaves become coarser and more pungent. It is inadvisable to buy pots of seedlings from garden centres for this reason: they are very liklely to bolt when planted out. The younger the leaves, the more appealing their flavour, hence their widespread use as microgreens, seed sprouts and cut-and-come- again baby leaves. It responds well to cut-and-come-again treatment at every stage. Its fast growth makes it very useful for intercropping.

In temperate climates, it is possible to have a year-round supply, sowing outdoors from early spring (as soon as the ground is workable) until autumn, followed with sowings under cover. I sow in my polytunnel in mid- to late winter for very early crops and early to mid-autumn for late crops. It is one of the first and last crops I sow every year.

Rocket is normally sown in situ; it doesn’t transplant well. Either grow it as cut-and-come-again seedlings or as single plants, spaced 15cm/6in apart. Make summer sowings in light shade, and keep them well watered. You can cut seedlings within three or four weeks of sowing, and make as many as four further cuts. It is easy to save seed, especially from plants seeding in early summer. The main problem is flea beetle, to which summer sowings are particularly susceptible (see here).

Wild rocket, being perennial, can be cut down at the end of the season and left to regenerate the following year. Generally speaking wild rocket is slower to germinate, and growth is slower than annual rocket. With both types, it is easy to save your own seed. In addition, plants left in the ground will often self-seed.

Salad rocket is noted for its levels of vitamins, minerals and glucosinolates. This last has led to current research into its potential as a crop grown to control soil nematodes, notably in potatoes. Who knows, this might become a practical means of biological control for gardeners in the future. Rocket is a powerful plant.

Straight-leaved rocket

Rocket with indented leaves

Red-veined rocket

Varieties A selection of reliable varieties from a wide and expanding choice:

Annual rocket: ‘Apollo’, ‘Esmee’, ‘Green Brigade’, ‘Serrata’, ‘Sorrento’, ‘Victoria’ Wild rocket: ‘Napoli’; ‘Tirizia’; ‘Dragon’s Tongue’, ‘Fireworks’ (both red veined); ‘Wasabi’ (exceptionally pungent)

Turkish rocket Bunias orientalis

True Turkish rocket is a very hardy perennial with dandelion-like leaves, and edible flower buds. It is native in southern and eastern Europe where it is used as greens and in salads. It was traditionally forced and blanched like seakale. Belgian nurseryman Peter Bauwens recommends growing a few plants for use in spring, which he blanches (see here). Germination can be slow, but Turkish rocket is trouble free, and self-seeding. Strains of salad rocket are sometimes misleadingly sold as ‘Turkish rocket’.

–––––

Garden cress (pepper cress) Lepidium sativum