finishing

touches

—

So often it is the finishing touches which transform a salad from the mundane to the unforgettable. It can be the brightness of flower petals sprinkled over the top, the subtlety of flavour conferred by herbs, or the palate tickled with a garden weed or even a wild plant.

Herbs

The deft use of herbs transforms a salad. Add a little chopped coriander or fenugreek to evoke the Orient; a few leaves of balm or lemon thyme for a hint of lemon; chervil or sweet cicely to create the subtle tones of aniseed. Or go for a more daring flavour with lovage, or a generous sprinkling of dill, or a little sage, tarragon or basil. Almost any culinary herb can find a role in salad making: experiment with what you have to hand. The only guiding principle should be that the stronger the herb, the more lightly it is used. The eminent twentieth-century gardening writer Eleanour Sinclair Rohde put this neatly: ‘It is just the suspicion of flavouring all through the salad that is required, not a salad entirely dominated by herbs.’ She would mix a teaspoon of as many as twenty finely chopped herbs to sprinkle into a salad.

Don’t overlook the decorative qualities of herbs in salads. Many have variegated and coloured forms – marjoram, mint and thyme spring to mind – and many have leaves of outstanding beauty; the delicate tracery of salad burnet (see here), sweet cicely, dill and the bronze and green fennels, for example. Add any of these, freshly picked, for a last-minute garnish.

It is a truism that fresh herbs are infinitely better-flavoured than dried or preserved herbs. In temperate climates most culinary herbs die back in winter, but chervil, caraway, coriander and parsley are some that can be grown under cover for use fresh in winter. Others can be potted up in late summer and brought indoors. Basil, thyme, mint, winter savory and marjoram can be persuaded to provide pickings from a winter windowsill.

Although many herbs can be preserved and are useful in cooking, only a handful, such as some mints, retain their true flavour. Several of the more succulent herbs, such as chives, parsley and basil, can be deep-frozen as sprigs or chopped into ice-cube trays filled with water. Thaw the cubes in a strainer when you need to use the herb. Otherwise herbs are usually preserved by drying. Pick them at their peak, just before flowering, and dry them slowly in a cool oven, or hang them indoors, covered with muslin to prevent them from becoming dusty. When they are completely dry, store them in airtight jars.

Herbs are worth growing for their ornamental qualities. Walls, patios, dry areas and spare corners can be carpeted with thymes, lemon balm or creeping mint. Ordinary and Chinese chives, parsley, hyssop and savory make effective edging plants, while mature plants of fennel, angelica and lovage are handsome features in their own right. So many are colourful when in flower. All in all, a salad lover’s garden should be brimming with herbs.

Here are brief descriptions and cultural information for some of the most useful salad herbs, listed in alphabetical order by common name. For more detailed cultural information, see Further reading.

–––––

Angelica Angelica archangelica

A beautiful, vigorous biennial, growing up to 3m/10ft high when flowering, angelica is one of the first herbs to reappear in spring. The typical angelica flavour is found in the leaves, stems and seeds. All can be used in salads when young.

Angelica requires fairly rich, moist soil and needs plenty of space. Sow fresh seed in situ in autumn, thinning the following spring to at least 1m/3ft apart; very young seedlings can be transplanted. Angelica dies after flowering in its second season, but in suitable sites perpetuates itself with self-sown seedlings.

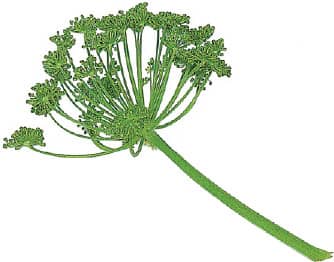

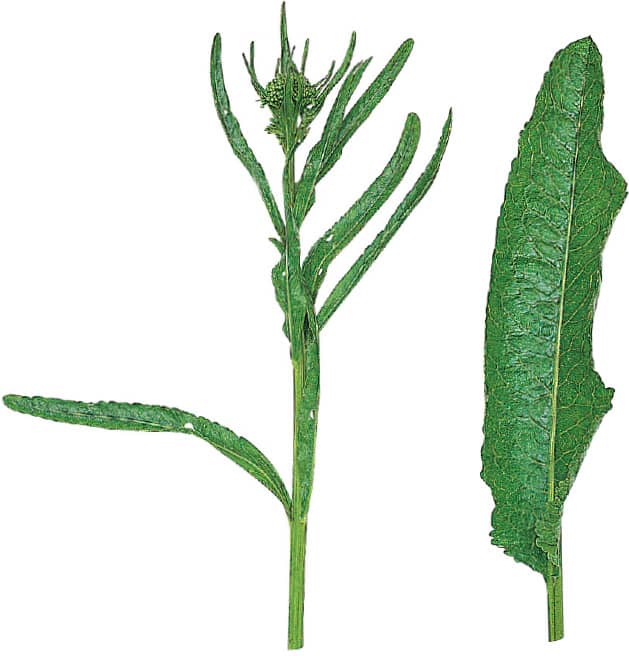

Angelica seed head

Angelica leaves

–––––

Basil Ocimum spp.

The basils are wonderfully aromatic tender annuals, used in many salad dishes but above all associated with tomatoes. They are in the main clove-flavoured. There are many varieties. Lettuce-leaved (Neapolitan) is the largest, growing up to 45cm/18in high with huge leaves; common, sweet or Genovese basil has medium-sized leaves; bush basil is a smaller plant with smaller leaves again, while the various forms of ‘Greek’, fine-leaved or miniature basil have tiny, strongly flavoured leaves and are exceptionally compact and low-growing. There are red-leaved forms, and many varieties with distinct flavours including cinnamon, anise, lemon and lime – the last two being outstanding.

Basils cannot stand frost or cold conditions. In cool temperate climates, grow them in a very sheltered, warm, well-drained site or under cover. Sow indoors in late spring, planting outdoors or under cover about 12cm/5in apart, depending on variety. To prolong the season, make a second sowing in early to mid-summer of bush or compact basil, potted into 10–12cm/4–5in pots. Bring indoors in early autumn. They may provide fresh leaf for several months.

Purple basil

Bush basil seedling

Sweet basil

Lemon-scented basil

–––––

Chervil Anthriscus cerefolium

Chervil is a fast-growing, hardy annual or biennial, about 25cm/10in high before seeding. The delicate leaves have a refreshing aniseed flavour, and can be chopped like parsley into many salad dishes. A great asset in temperate climates is that it remains green in winter.

Chervil is not fussy about soil. For summer supplies, sow in situ in spring in a slightly shaded situation, thinning to 10cm/4in apart. Keep the plants well watered. For autumn to early spring supplies, sow in situ in late summer, either outside or under cover for good-quality winter plants; or sow in modules and transplant under cover. Chervil can be cut several times before it runs to seed; if left to flower, it usefully seeds itself.

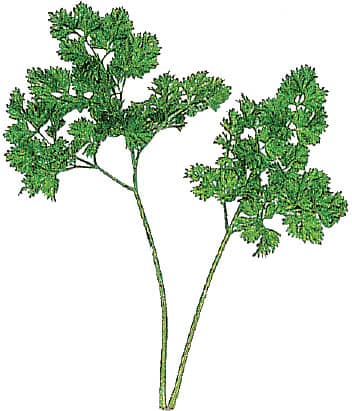

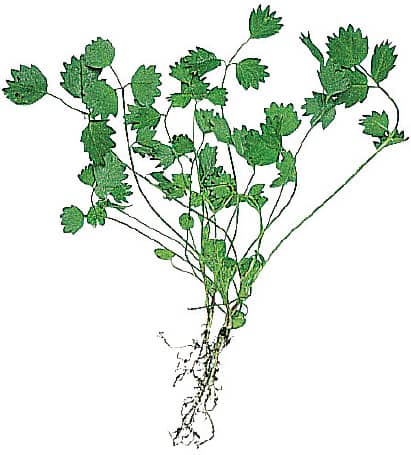

Chervil

–––––

Coriander (cilantro, Chinese parsley) Coriandrum sativum

Coriander is an annual, 12cm/5in high in its leafy stage and over 45cm/18in high when seeding. The leaves, with their musty curry flavour, make a unique contribution to salad dishes, as do the flowers. It is also grown for the strong-flavoured seeds, commonly used in curries. Coriander grows best in cool conditions, in light soil with plenty of water throughout growth. It tolerates light frost, and stands well in winter under cover.

In temperate climates, it can be sown throughout the growing season, though it may run to seed rapidly in hot weather. Sow in succession outdoors from early spring to early autumn, in situ, either fairly densely to cut as cut-and-come-again seedlings or thinning to 15cm/6in apart for larger plants; or multi-sow several seeds per module, planting out 15cm/6in apart. The hard outer seed coat sometimes prevents germination: if so, crack the ‘pods’ gently with a rolling pin.

Earlier and later sowings can be made under cover, and early sowings can be grown to maturity under fleece. Cut leaves at any stage up to about 12cm/5in high. The flavour deteriorates once the plants start running to seed. Older varieties of coriander, such as ‘Santo’ and ‘Leisure’ are being joined by improved, larger leaved, slower bolting varieties such as ‘Cadiz’, ‘Calypso’ and ‘Cruiser’. If you specifically want the seed, rather than leaf, for culinary use, leave a few plants to seed relatively early in the season, so they have time to ripen and dry. Some large seeded varieties, such as ‘Moroccan’, were traditionally used for coriander seed, but are no longer easily available. Coriander leaf can be frozen but does not dry well.

Broad-leaved parsley

Coriander leaves

–––––

Dill Anethum graveolens

This feathery annual is grown for the seeds and seedheads, which are widely used in pickling cucumbers, and for the delicately flavoured leaves, easily chopped into salads The mature plant can be up to about 80cm/32in high.

Grow dill leaf like coriander (see here) using improved varieties such as ‘Domino’ and ‘Dukat’ where available. The problem with dill is its tendency to run to seed rapidly. Nor does it thrive in cold, wet conditions. So in cool climates the solution lies in sowing little and often, for example a small patch, or in a pot, in a greenhouse or polytunnel.

When grown as cut-and-come again seedlings, they will normally regenerate at least once after cutting.

For seed heads, and hence seeds for culinary use, sow in early summer by broadcasting, or in rows 23cm/9in apart, thinning to about 15cm/6in apart.

Dill is very pretty at every stage from seedlings to seeding. Plants left in late summer will often reseed themselves.

Dill leaf

–––––

Fennel Foeniculum vulgare

The herb fennel (unlike Florence fennel see here) is a hardy perennial, growing up to 11/2m/5ft high. The common green form has beautiful gossamer leaves, with a light aniseed flavour; the stunning bronze fennel (F. v. ‘Purpureum’) is milder-flavoured. The chopped leaves and peeled young stalks can be used in salads, as can the seeds.

Fennel tolerates most well-drained soils. Sow in spring in situ or in modules for transplanting, spacing plants 45cm/18in apart. Plants can also be propagated by dividing up clumps in spring. Plants tend to run to seed in mid-summer, but for a constant supply keep them trimmed back to about 30cm/12in high and remove flower spikes. Bronze fennel in particular can self-seed prolifically and become invasive – but deserves a place in every decorative potager. Renew plants when they lose their vigour.

–––––

Hyssop Hyssopus officinalis

Hyssop is a short-lived, shrubby, hardy perennial, about 45cm/18in high: it can be kept trimmed to make a neat, low hedge. The shiny little leaves have a strong, savory-like flavour, and remain green late into winter. Use the young leaves sparingly in salad: they combine well with cucumber and onions.

The beautiful blue, pink or white flower spikes attract bees and butterflies.

Propagate hyssop by taking softwood cuttings from a mature clump in spring, or sow indoors in spring and early summer, eventually planting seedlings about 30cm/12in apart. Seeds need light to germinate, so should be sown on the surface covered lightly with perlite or vermiculite. Pinch back shoot tips to keep plants bushy, and prune back hard in spring. Plants need renewing every three or four years.

Hyssop

–––––

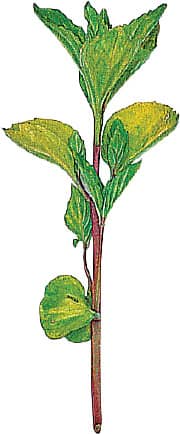

Lemon balm Melissa officinalis

This easily grown hardy perennial forms clumps up to 60cm/24in tall. Delightful lemon-scented leaves can be chopped into salad dishes. Lemon balm tolerates a wide range of soil and situations, and is an excellent ground-cover plant. Propagate by taking a rooted piece from an old plant; or sow seed indoors in spring, planting 60cm/24in apart. Cut plants back hard in the autumn. There are pretty variegated and golden forms.

Variegated lemon balm

Green lemon balm

–––––

Lovage Levisticum officinale

This handsome hardy perennial grows up to 21/2m/8ft tall, and is one of the first to emerge each spring. The glossy leaves have a strong but superb celery flavour. Rub them into a salad bowl, or chop them sparingly into salads. The leaf stalks can be blanched like celery.

Lovage thrives in rich, moist soil and tolerates light shade. Sow fresh seed indoors in spring or autumn, eventually planting at least 60cm/2ft apart. (One plant is enough for most households.) Alternatively, divide an old clump in spring, replanting pieces of root with active shoots. Lovage often seeds itself, and young seedlings can be transplanted.

Lovage

–––––

Marjoram and origanum Origanum spp.

There are many forms and varieties (and much confusion over naming) of these perennial Mediterranean herbs with gentle, aromatic flavours. Several compact forms are only 15cm/6in high, but taller varieties grow up to 45cm/18in. Gold-leaved, gold-tipped and variegated varieties may be less flavoured, but they are very decorative in salad dishes and in the garden. My favourites for salads are the half-hardy sweet or knotted marjoram (O. majorana) with its lovely soft leaves; gold marjoram (O. vulgare ‘Aureum’); the hardy winter marjoram (O. heracleoticum) (there is some confusion over the name), which remains green in temperate winters, and the well-flavoured pot marjoram (O. vulgare or O. onites).

Marjorams grow best in well-drained, reasonably fertile soil in full sun, though golden-leaved varieties, which tend to get scorched in hot weather, can be grown in light shade. Some varieties, including sweet marjoram, can be raised from seed, sown indoors in spring and eventually planted 12cm/5in apart. Many others are propagated by softwood cuttings taken in spring, or by dividing established clumps. It is often possible to pot up plants for use indoors in winter. On the whole marjorams dry well.

Winter marjoram

Forms of golden marjoram

–––––

Mint Mentha spp.

The majority of the many hardy perennial mints can be used, albeit sparingly, in salad dishes, imparting that special ‘minty’ flavour. My own favourites for flavour are apple mint (M. suaveolens), spearmint (M. spicata) and raripila or pea mint (M. rubra var. raripila). For their decorative quality, I grow the cream and green pineapple mint (M. suaveolens ‘Variegata’) and the variegated, gold and green Scotch or ginger mint (Mentha x gracilis). Each mint has its own subtly different flavour: yours to discover!

Most mints spread rapidly in moist, fertile soil and tolerate light shade. The easiest way to propagate is to lift and divide old plants in spring or autumn. Very few are raised satisfactorily from seed. Replant small pieces of root 5cm/2in long, laid horizontally 5cm/2in deep, 23cm/9in apart; or plant shoots with attached roots. Replant mints every few years in a fresh site if they are losing vigour. Plants die back in winter. In autumn, transplant a few into a greenhouse, or into pots or boxes: they will start into growth early in spring. Most mints retain their flavour well when dried.

Raripila mint

Spearmint

Apple mint

Ginger mint

Pineapple mint

–––––

Mitsuba (Japanese parsley, Japanese honewort) Cryptotaenia japonica

This hardy, evergreen perennial is a woodland plant, growing about 30cm/12in high. It has long leaf stalks and pale leaves divided into three leaflets, not unlike flat parsley in appearance. Stems and leaves are used raw in salads and have a delicate flavour, encompassing that of parsley, celery and angelica. The seeds can be sprouted. It does best in moist, lightly shaded situations. In the West it is mainly grown as single plants, often edging shaded borders. In its native Japan it is also grown densely, often in polytunnels, to get fine, virtually blanched, very tender stems.

Although perennial, mitsuba is best grown as an annual. Sow in situ from late spring to early autumn (optimum soil temperature is about 25°C/77°F), making successive sowings for a continuous supply. Thin plants to 15cm/6in apart. They will be ready for use within about two months. Alternatively, plant under cover in early autumn for use during winter. Plants left in the ground may seed themselves for use the following year.

–––––

Parsley Petroselinum crispum

Parsley is a biennial, growing 10–45cm/4–18in high. Its characteristically flavoured leaves are widely used in cooking and as a garnish. There are two types: curly, and plain or broad-leaved, of which ‘French’ and ‘Giant Italian’ are typical varieties. Curly parsley is more decorative, but the plain-leaved varieties are more vigorous, seem to be hardier and are more easily grown. Most chefs consider them better-flavoured.

Parsley needs moist conditions and fertile soil. For a continuous supply, sow in spring for summer use, and in summer for autumn-to-spring supplies. Sow in situ or in modules for transplanting when seedlings are still young. Failures with parsley stem from it being slow to germinate. Once sown, take care to keep the soil moist until seedlings appear. Thin or plant 23cm/9in apart. Parsley normally dies back in winter after moderate frost. Keep a few plants cloched or plant in a greenhouse in late summer/early autumn for winter-to-spring supplies. Cut off flowering heads to prolong the plant’s useful life. If left, however, they often self-seed.

Curly parsley

–––––

Sage Salvia officinalis

The sages are moderately hardy, evergreen perennials, growing 30–60cm/12–24in high. The large, soft, subdued grey-green leaves of common broad-leaved and narrow-leaved sage (S. lavandulifolia) are strongly flavoured. Only slightly less so but very decorative are gold sage (S. o. ‘Icterina’), the less hardy, tricolor sage (S. o. ‘Tricolor’) with pink, purple and white leaves, and the red or purple sage (S. o. Purpurascens Group), frequently mentioned in traditional salad lore. See also Edible flowers).

Sages need well-drained, light soil and a sunny, sheltered position. For common sage, sow seed indoors in spring, planting out 30cm/12in apart the following spring. With other varieties, propagate from heel cuttings taken in early summer. To keep plants bushy, prune lightly after flowering in late summer and harder in spring. Sage flowers are edible, the beautiful red flowers of the tender pineapple sage (S. elegans) being deliciously sweet in salads.

Narrow-leaved sage

–––––

Summer and winter savory Satureja hortensis and S. montana

Summer savory is a bushy annual that grows up to 30cm/12in high with fairly soft leaves, while winter savory is a more compact, hardy, semi-evergreen perennial, with narrow, tougher leaves. Both are almost spicy in flavour, and are said to enhance other flavours in cooking. Use them sparingly in salad dishes.

Savories need a sunny position and well-drained, reasonably fertile soil. Sow in spring indoors, but do not cover the seeds, as they need light to germinate. Plant 15cm/6in apart. Winter savory can also be propagated from softwood cuttings taken in spring. In late summer, pot up a winter savory plant for winter use indoors: they are very pretty when they burst into renewed growth in spring.

Winter savory

–––––

Sweet cicely Myrrhis odorata

Sweet cicely is an attractive, hardy perennial, often growing 11/2m/5ft high; its leaves resemble chervil and have a sweet, aniseed flavour. They are a delight chopped into salad or used whole as garnish, but pick them just before you need them, as they wilt almost instantly. The substantial roots can be boiled and sliced, and the immature seeds have a strong aniseed flavour, both a great contribution to salads. Sweet cicely starts into growth early in the year, dying back late, so has a long season of usefulness. It is sometimes found in the wild.

It grows best in rich, moist soil in light shade. Sow fresh seed outdoors in autumn, thinning to 8cm/3in apart, and plant in a permanent position the following autumn 60cm/24in apart. Or sow in modules, keeping them outside during winter. Plants can also be propagated by dividing roots carefully in spring and autumn. Replace plants only if they are losing vigour.

Sweet cicely

–––––

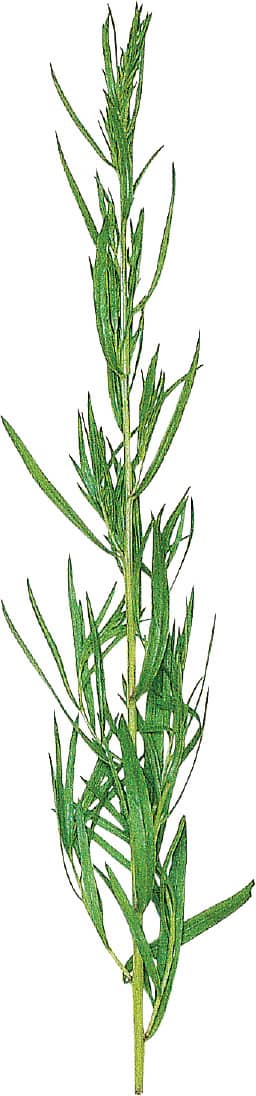

French and Russian tarragon Artemisia dracunculus and A. d. dracunculoides

French tarragon is a narrow-leaved, moderately hardy perennial, growing about 1m/3ft high, while Russian tarragon is larger, coarser and much hardier. The aromatic leaves of both have a distinct flavour, but the Russian is widely believed to be less strong. It is adequate for salad dishes, but French tarragon is preferable for flavouring vinegar and in cooking.

Grow tarragon in a well-drained, sheltered position, preferably on light soil. Russian tarragon can be raised from seed sown indoors in spring, but French tarragon rarely sets seed, so propagate it by dividing old plants or from root cuttings. Plant 60cm/24in apart. In cold areas, cover French tarragon roots with straw in winter. Plants decline after a few years and should be replaced.

Russian tarragon

–––––

Thyme Thymus spp.

The culinary thymes are pretty, creeping and low-growing herbs, sun-loving and mostly hardy perennials. Their tiny leaves can be added to salads, dressings and vinegars. The following are varieties I have found rewarding to grow for salads: the traditionally-flavoured common and large-leaved thymes (T. vulgaris and T. pulegioides); lemon-scented thyme (T. citriodorus); T. ‘Fragrantissimus’, which has an orange scent; and caraway thyme (T. herba-barona).

Grow thyme in a sunny spot on well-drained, but not particularly rich soil. Thymes thrive in dry conditions and do well in containers. Common thyme can be raised from seed sown in spring indoors, on the surface covered with perlite or vermiculite. The seed is tiny, so can be mixed with sand to make sowing easier. Space plants 30cm/12in apart. Propagate other varieties by dividing established plants in spring or autumn, or taking softwood cuttings in spring or summer. Trim back plants after flowering. Renew them every three years or so once they become straggly. They can be potted up for winter use indoors.

Common thyme

Broad-leaved thyme

Flowers

Using edible flowers in cooking and salads is an ancient, universal tradition. They are often added just for their colour and fragrance, but some – nasturtiums, day lilies and anise hyssop, for example – have real flavour. In the past flowers were collected from the wild, but today the need to preserve wild species is paramount, so pick only where they are abundant and it is not illegal. Or grow your own.

Gather flowers early in the day, when the dew has just dried on them. Pick or cut them with scissors; handle them gently and carry them in a flat basket to avoid bruising.

Where flowers are invaded by insects (such as pollen beetle), lay them aside so the insects can creep away! If essential, wash flowers gently, lightly patting them dry with paper towelling. Keep them in a closed bag in a refrigerator until needed. Refresh them by dipping in ice-cold water just before use.

It is mainly petals that are used in salads. With daisy-like flowers, pull them gently off the centre. Small, soft flowers can be used whole, but large flowers may have rough, hard or strongly flavoured parts. Taste cautiously and remove these parts if necessary. Sprinkle flowers or petals over the salad at the last moment, after dressing, as dressings discolour them and make them soggy. Use either one or two types, or a confetti mixture, being careful not to overwhelm the salad. Charm lies in subtlety.

Very many cultivated and wild plants have edible flowers but there is only space for brief notes on a few of them. Be sure to identify plants correctly before eating the flowers; some common garden flowers – aquilegia, cyclamen, daffodils, delphiniums to name a few – can be toxic. (For identification and cultivation, see Further reading.) Plants are listed here under common names but alphabetically by Latin names.

–––––

Anise hyssop Agastache foeniculum

A hardy perennial about 60cm/24in high. The tiny flowers in the flower spikes have an almost peppermint flavour. The young leaves are edible raw. (Advisable to avoid when pregnant.)

–––––

Hollyhock Alcea rosea

These tall, cottage garden plants have beautiful red, yellow, rose and creamy flowers. Petals and cooked buds are used in salads. They are perennial but best grown as biennials to avoid infection with rust.

Hollyhock flower and bud

–––––

Anchusa Anchusa azurea

A perennial growing 120cm/48in tall with bright, gentian-blue flowers which look superb mixed with red rose petals in a salad. After flowering in early summer cut back the main stem to encourage secondary shoots to prolong the flowering season.

Anchusa

–––––

Bellis daisy Bellis perennis

The many cultivated rose-, red- and white-flowered forms of the little white lawn or English daisy are all edible. Use the daintier, small-flowered varieties whole, but with the larger, double varieties, use only the petals. Treat them as biennials, sowing in autumn and spring for almost year-round flowers. Lawn daisies close quickly so pick just before use. (Daisy family flowers should be avoided by sufferers from hayfever, asthma or severe allergies.)

Different forms of bellis daisy

–––––

Borage Borago officinalis

This self-seeding annual grows about 120cm/48in high, typically a haze of sky blue flowers all summer though there is a less common, white-flowered form. The flowers are delightfully sweet, but remove the hairy sepals behind the petals before eating them. The flowers look wonderful frozen into ice cubes for drinks. We leave a few plants to seed in our polytunnel to give us early spring flowers. Finely chopped young leaves are edible raw in salads. (Avoid when pregnant or breastfeeding.)

Blue-flowered borage

–––––

Pot marigold Calendula officinalis

The petals of these vibrantly coloured annuals were traditionally used for seasoning and colouring cakes, cooked dishes and salads. Today’s varieties are all shades of orange, yellow, bronze, pink and brown, in single- and double-flowered forms. If regularly dead-headed they flower from early spring until the first frost. They often self-seed. Flowers can be dried for winter use, and in the past were pickled.

Pot marigold

–––––

Chicory Cichorium intybus

Any cultivated or wild chicory plant left to seed in spring produces huge spires of light blue, occasionally pink, flowers. Use the petals or whole flowers in salads: they have a slightly bitter but distinct ‘chicory’ taste. The flowers close and fade rapidly, often by midday, but try picking early and keeping in a refrigerator. They can be pickled: the colour is lost but a faint flavour remains. (For cultivation, see Chicory.)

–––––

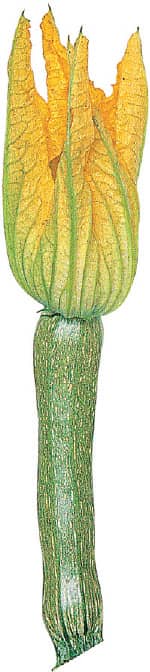

Courgettes, marrows, squashes, pumpkins Cucurbita spp.

The buttery yellow flowers of these and many oriental gourds have a creamy flavour and crisp texture. They can be cooked, but can also be used raw, whole or sliced, in salads. Pick the small male flowers once fruits are setting (leave a few for pollination) and any spare female flowers, identified by the tiny bump below the petals.

Courgette

–––––

Carnations, pinks, sweet William Dianthus spp.

The raw flowers of these popular garden plants have varying degrees of fragrance and flavour, from mild to musky to a strong scent of cloves. The white heel at the base of the petals can be bitter and is best removed.

–––––

Garland chrysanthemum Glebionis coronarium

While various chrysanthemum flowers have been used for cooking in the past, the petals were often bitter unless given special treatment. This type, grown for its edible leaves, has mild-flavoured flowers which make a beautiful garnish. Only use the petals, discarding the bitter flower centre. For cultivation see here. In China and Japan special varieties of the tender, perennial florist chrysanthemum are cultivated for culinary purposes.

–––––

Sunflower Helianthus annuum

The flower petals of this easily grown, highly popular annual are edible raw in salad and have a mild flavour, sometimes described as ‘nutty’. The green buds can be blanched and eaten tossed in garlic butter.

–––––

Lavender Lavandula spp.

In the past salads were served on beds of lettuce and lavender sprigs but the flowers are strongly flavoured and should be used sparingly. There are blue-, purple-, pink- and white-flowered varieties.

Lavender

–––––

Day lily Hemerocallis spp.

The flavour of raw day lily flowers varies widely. American writer Cathy Barash (see Further reading) believes the darker colours tend towards bitterness, while pale yellows and oranges are sweeter. My light orange variety (probably H. citrina), from a Chinese research station, has a superb, vanilla flavour and crisp texture. Taste before use – and only eat in moderation! Dried day lily flowers are widely used in Chinese cooking.

Day lily

–––––

Sweet bergamot (bee balm, Oswego tea) Monarda didyma

The colourful flowers of these perennials have distinct ‘mint with hints of lemon’ flavours. I love them mixed with borage in salads. Some F1 hybrid varieties are reputedly bitter. Dried flowers are used for a delicately flavoured tea.

–––––

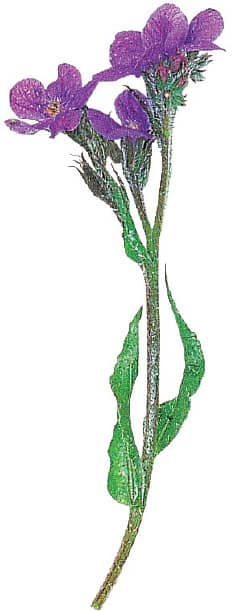

February orchid Orychophragmus violaceus

The fabulous lilac flowers are stunning in winter and spring salads. For cultivation see here.

–––––

Jacob’s ladder Polemonium caeruleum

The sweetly scented flowers of the many species and varieties of these pretty hardy perennials are pleasantly flavoured and colourful in salads.

–––––

Primrose Primula vulgaris and Cowslip P. veris

In the past these mild-flavoured flowers were collected from the wild in spring. Today, they, and the many colourful hybrids, can be cultivated for salads. Primula flowers can be crystallised, and cowslip flowers were traditionally pickled.

–––––

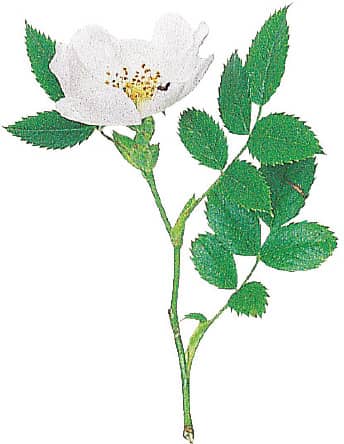

Rose Rosa spp.

Most rose petals can be used in salads, but fragrant roses, especially the classic old roses – R. rugosa, the Apothecary rose R. gallica, and the Damask rose R. damascena – have the most flavour. Always try petals before using; some have a bitter aftertaste, often found in the white part at the base of petals.

Wild rose

–––––

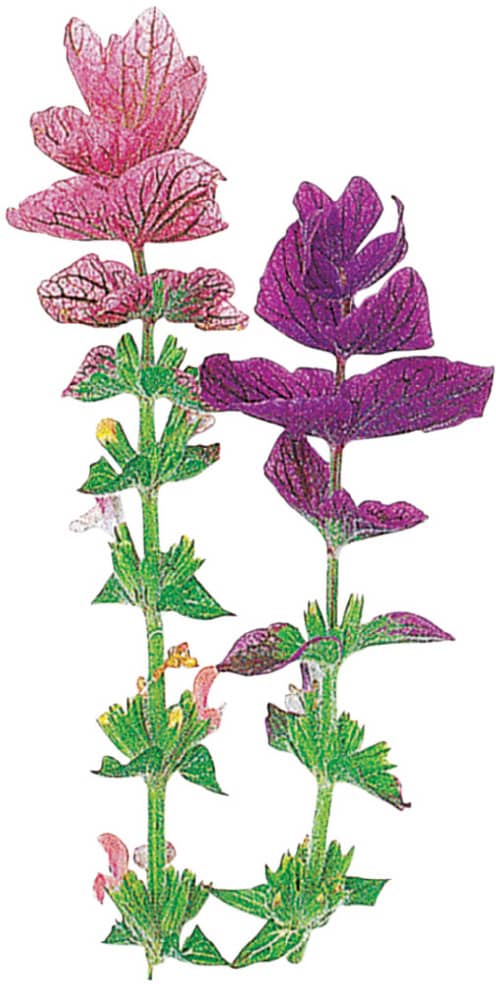

Sage Salvia spp.

The blue, white or pink flowers of culinary sage (S. officinalis) have a pleasant subdued sage flavour, are fairly firm and stand well in salads. The colourful bracts of clary sage (S. sclarea) and painted sage (S. horminum) have a faint mint flavour. The sweet, scarlet flowers of pineapple sage (S.elegans) really do have a hint of pineapple in them. For cultivation, see here.

Painted sage

–––––

Scorzonera Scorzonera hispanica and Salsify Tragopogon porrifolius

The plump flower buds are used cooked and cooled, and the more faintly flavoured petals – yellow in scorzonera, lilac in salsify – are strewn on salads. The flowers may open only briefly in the morning sunshine, then close firmly. If the petals are wanted later in the day try picking when open and keeping them in a closed bag in a refrigerator until needed.

Salsify half-open flower and buds

Scorzonera flower and buds

–––––

Tagetes (Signet marigold) Tagetes tenuifolia

The sparkling little flowers of the ‘Orange Gem’, ‘Tangerine Gem’ and ‘Lemon Gem’ varieties have fruity, fragrant flavours. They are easily grown tender annuals with a long flowering season, making neat edgings to flower and vegetable beds.

–––––

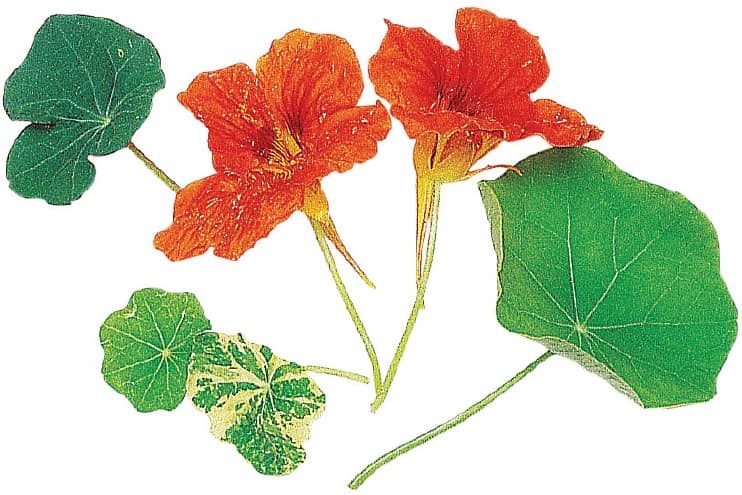

Nasturtium Tropaeolum majus

These easily grown annuals, with trailing and dwarf forms, are of ancient use in salads. Buds and flowers are piquant, the leaves are peppery and seeds are pickled as capers. For salads grow the dainty, variegated-leaved T.m. Alaska series: their vibrantly coloured flowers retain a ‘spur’, which I think keeps them fresh longer once picked than modern spurless varieties. Also pretty is the red-leaved T.m. Empress of India’. Tuberous-rooted nasturtium (mashua), T. tuberosum, has edible flowers. Nasturtiums often reseed profusely.

Nasturtiums with plain, red and variegated leaves

–––––

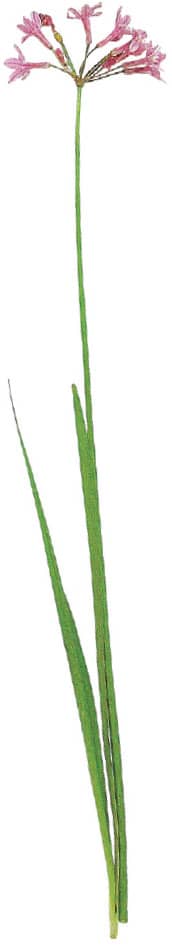

Society garlic Tulbaghia violacea

This moderately frost-tolerant perennial has beautiful, fragrant, usually lilac flowers, with a mild garlic flavour. The leaves also are garlic-flavoured. For cultivation see Chinese chives (which also has edible flowers).

Society garlic

–––––

Broad bean Vicia faba

The flowers are decorative and well flavoured. For cultivation see here.

–––––

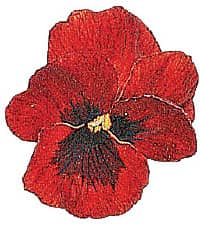

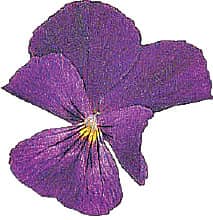

Pansy and violas Viola spp., Sweet violet V. odorata

All supply colour and texture, rather than flavour, to salads though in the past violet flowers were eaten with lettuce and onions! The tiny heartsease flowers, V. tricolor, are delightfully delicate. Winter-flowering pansies meet a need for colour in winter salads.

Garden pansy

Viola

–––––

Yucca Yucca spp.

The white flowers of these handsome, moderately hardy perennials have a delicious sweet flavour and crunchy texture – a great addition, raw, in salads.

Wild plants and weeds

Our cultivated vegetables have all evolved from wild plants, so it is not surprising that the countryside is still a treasure trove of edible plants. Over the centuries some of these wild plants have invaded arable fields and gardens, becoming weeds. In this less competitive environment they grow lushly, providing tender pickings for salads. Many have wonderfully lively flavours that truly enrich a salad. They are probably best worked into mixed salads in small quantities, rather than made into a salad composed entirely of wild plants.

The golden rule with weeds and wild plants is to pick the leaves small and young, as most become tough as they mature. Peasant communities all over the world scour fields and mountains in early spring for those very first leaves. Wild plants have always been valued for their medicinal and ‘health-giving’ properties; we now know that many are rich in vitamins and minerals.

It is absolutely essential to identify wild plants accurately, as a few are easily confused with poisonous species. Identify them with a good botanical text or, if you have no botanical knowledge, be guided initially by an expert. You will soon get to know the common garden weeds and wild plants in your area. Never go just by a picture in a book. Two people I met did so, confused ground elder with dog’s mercury, and found themselves in hospital as a result.

Seed of some wild plants is now widely available, so it is possible to grow your own. There is only space here for brief notes on a few of the many edible wild plants. They are listed by common name, in the alphabetical order of their Latin names as the common names are often misleading. For identification, see Further reading. There are few specialist seed suppliers, some wild plants and weeds can be found in herb and general seed catalogues.

–––––

Yarrow (Milfoil) Achillea millefolium

Very common weed, remaining green much of the year. Strongly flavoured.

Yarrow

–––––

Ground elder Aegopodium podagraria

Pernicious weed with a delightful angelica flavour. Do not confuse it with the similar but poisonous dog’s mercury (Mercurialis perennis). In trying to eradicate ground elder Peter Harper, of the Centre for Alternative Technology, discovered that by cutting it back, then covering with 15cm/6in of sawdust or sand, the first leaves to grow through could be steamed for salad, and the blanched shoots below could be eaten raw. A second, weaker crop would follow.

Ground elder

–––––

Garlic mustard (Jack-by-the-hedge) Alliaria petiolata

Common hedgerow weed with an appealing, faint garlic flavour.

–––––

Wild garlic (Ramsons) Allium ursinum and A. spp.

The leaves have a strong garlic flavour. Leaves, stems, bulbs and flowers of many wild alliums have a mild to strong garlic flavour, including crow garlic (A. vineale), keeled garlic (A. carinatum) and sand leek (A. scorodoprasum).

–––––

Wild celery (Smallage) Apium graveolens

Grows in damp places. Chop leaves and young stems into salads. Do not confuse it with poisonous hemlock (Conium maculatum) or water dropwort (Oenanthe crocata).

–––––

Burdock Arctium lappa and Lesser burdock A. minus

Rampant plants, used all over the world cooked and raw. For salads, pick the leafy stems of young shoots in spring, strip off the peel and cut into 5cm/2in pieces. Intriguing flavour.

–––––

Horseradish Armoracia rusticana

For cultivation, see here.

Horseradish

–––––

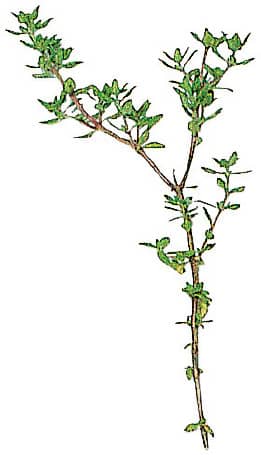

Shepherd’s purse Capsella bursa-pastoris

Very common weed, green much of the year. Basal leaf rosettes and stem leaves are excellent raw; their distinctive flavour is due to sulphur. Cultivated in China for use raw and cooked. Said to be richer in vitamin C than oranges.

Shepherd’s purse

–––––

Hairy bitter cress Cardamine hirsuta

Very hardy, ubiquitous little weed appearing in autumn and spring. Cut the tiny, cress-flavoured leaves for salads. Seed pods explode when touched: thin out seedlings to get plants of a reasonable size. Cover them with cloches in autumn to increase their size and tenderness.

–––––

Lady’s smock (Cuckoo flower) Cardamine pratensis

Plant of damp meadows; remains green late in winter. The leaves have a watercress spiciness and are excellent in salads.

–––––

Red valerian Centranthus ruber

Red-and white-flowered forms, found on dry banks and walls; often cultivated in gardens. Use young leaves and flowers.

–––––

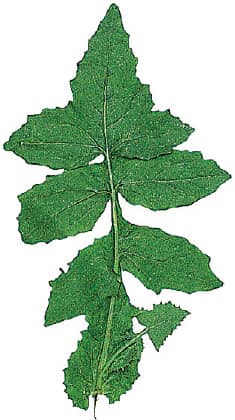

Fat hen (Lamb’s quarters) Chenopodium album

Very common arable weed, often found near manure heaps. It has a spinach-like flavour, and is excellent cooked like spinach or raw. American Indians made the seeds into cakes and gruel.

Fat hen

–––––

Ox-eye daisy (Marguerite) Chrysanthemum leucanthemum

The young leaves and flowers are used in salads in Italy.

–––––

Golden saxifrage Chrysosplenium oppositifolium

The cresson des roches of the Vosges mountains. Found in wet places.

–––––

Marsh thistle Cirsium palustre

A plant of damp places. Use young shoots and the stalks after removing prickles and peeling.

–––––

Rock samphire Crithmum maritimum

Found on cliffs and shingle. Use the fleshy leaves and stems cooked or pickled for salads.

–––––

Sea purslane Halimione portulacoides

Succulent grey-leaved plant of salt marshes. Wash off mud carefully. The leaves can be used fresh or pickled.

–––––

Woad Isatis tinctoria

The young leaves of this beautiful, easily cultivated plant are pleasant in salads.

–––––

Oyster plant Mertensia maritima

Pretty, seaside perennial. The fleshy leaves are reputedly oyster-flavoured and excellent in salads.

–––––

Watercress Nasturtium officinale

(Confusingly also called brooklime, the common name for Veronica beccabunga, a bitter but edible waterside plant.) Grows in running water: never pick from stagnant, contaminated or pasture water because of the risk of liver fluke infection. It is preferable to cultivate it (see here). Older leaves are more flavoured than young.

–––––

Evening primrose spp. Oenothera biennis, O. erythrosepala

The young leaves can be eaten raw; the roots, lifted before the plants flower, can be eaten after cooking.

–––––

Wood sorrel (Alleluia) Oxalis acetosella

The delicate, folded, clover-like leaves are among the first to appear in woods in spring. They have a sharp sorrel flavour.

–––––

Field poppy Papaver rhoeas

Common red-flowered poppy. The leaves are eaten in the Mediterranean, and the seeds used to decorate buns. Don’t confuse it with the toxic red-horned poppy (Glaucium corniculatum).

–––––

Buck’s horn plantain (Herba stella, Minutina) Plantago coronopus

A pretty perennial. The tough but tasty leaves are at their best in spring and autumn, remaining green well into winter. Blanch briefly in hot water to tenderize. Easily cultivated; sow in spring to late summer for an outdoor crop; sow early autumn under cover for a winter crop. Either grow single plants thinned or spaced 12cm/5in apart, or grow as cut-and-come-again seedlings. Cutting back flowers when they develop encourages further young leaves, but if flowers are left, it readily self-seeds.

–––––

Redshank (Red leg) Polygonum persicaria and Bistort P. bistort

The leaves of redshank, a common arable weed, are used cooked or raw. Do not confuse it with the acrid water pepper (Polygonum hydropiper). The late Robert Hart of ‘forest garden’ fame used the young shoots and leaves of bistort in salads.

–––––

Common wintergreen Pyrola minor

Berried evergreen, found in woods, moors, rocky ledges and sand dunes. The young leaves are used in salads in North America.

–––––

Red-veined sorrel Rumex sanguineus var. sanguineus

Has elegantly colourful but coarse-textured leaves. Soften them by briefly blanching in hot water. Easily cultivated, but potentially invasive.

Red-veined sorrel

–––––

Glasswort (marsh or sea samphire) Salicornia europaea

Primitive-looking plant of salt marshes and shingle beaches. Gather narrow, succulent young leaves in summer. Excellent raw or pickled.

–––––

Salad burnet Sanguisorba officinalis

A low-growing, very hardy perennial of the chalklands. The decorative, lacy leaves have a faint cucumber taste and remain green for much of winter. Use the youngest leaves raw in salads, but blanch tougher, older leaves in hot water. It is easily cultivated. Sow in spring, thinning to 10cm/4in apart. Remove flower stems.

Salad burnet

–––––

Reflexed stonecrop Sedum reflexum

Succulent perennial found wild on walls and rocks. Use of the leaves of this and other sedums in salads is ancient. Easily cultivated in dry places.

–––––

Milk or Holy thistle Silybum marianum

Striking plant with beautiful white-veined foliage. Use young leaves and peeled, chopped stems raw, roots raw or cooked. Easily cultivated.

–––––

Alexanders Smyrnium olusatrum

Tall, striking plant, common in coastal areas. Use of buds, young leaves, stems and spicy seeds (a pepper substitute) in salads is ancient. The stems used to be blanched. Not to be confused with poisonous hemlock and water dropwort found in similar places. (See Wild celery)

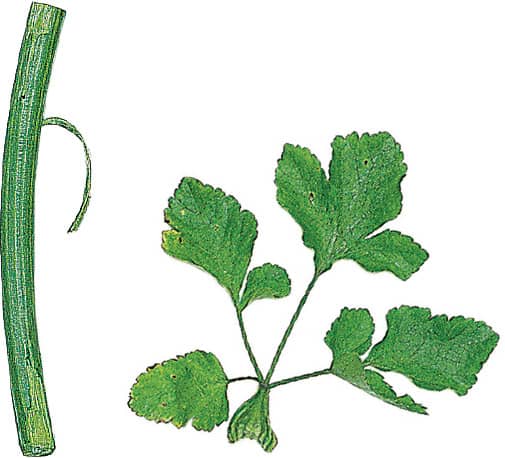

Alexanders – stem and leaf

–––––

Perennial sow thistle Sonchus arvensis, Prickly sow thistle S. asper and Smooth sow thistle S. oleraceus

Weeds found commonly on arable land. Pleasant taste, but trim off bristly parts.

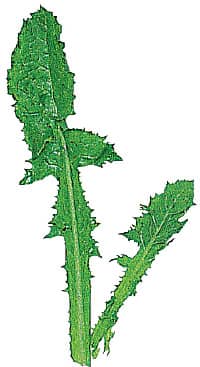

Prickly sow thistle

Smooth sow thistle

–––––

Chickweed Stellaria media

Very common garden weed, growing almost all year round. Use refreshingly tasty seedlings or larger plants if still succulent. (They are often best if grown in the shade.) Cut with scissors and leave to regrow.

Chickweed

–––––

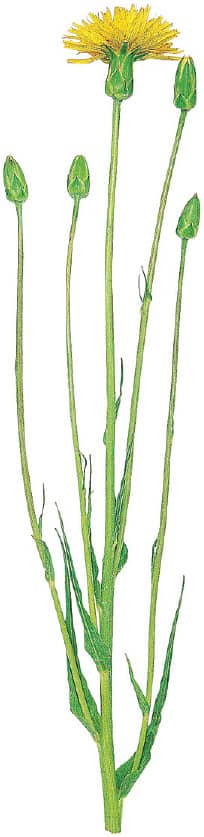

Dandelion Taraxacum officinale

For cultivation, see here.

Dandelion

–––––

Field penny cress Thlaspi arvense

Very common weed with delicious, spicy leaves.

Field penny cress