Equilibrium—Proceeding on an even keel

CHAPTER GOALS

• To develop a foundation of self-knowledge

• To decide what to change and what to do now

• To take first steps into your new life

• To understand and prevent relapse

Purpose: Preparing for a journey, while necessary, is a lot of work: charting your course, honing your skills, gathering your resources, anticipating challenges and troubled waters. It’s possible to spend a lifetime planning and arranging and waiting for the perfect moment to shove off. Ultimately, there is no perfect time, and no amount of preparation can be as valuable to you as the lessons you learn and the skills you develop by actually doing. This chapter is devoted to encouraging you to set sail and guiding you through some of the early demands on you and rough patches that may shake your resolve. Above all, you want to keep your forward motion, which requires—and also helps you maintain—your balance. This requires sharpening your self-knowledge or awareness, so that you can make deliberate choices based on your priorities; acting decisively on the decisions you make; and being able to maintain your larger perspective through failure and relapse by treating them as information to learn from.

Self-Knowledge and Personal Choice

Learning about yourself—developing insights into who you are, what you want, how you function—is self-knowledge (or self-awareness). Self-knowledge is a critical skill in fighting addiction. There is no one approach to overcoming addiction, and The PERFECT Program is designed to help you discover a path that honors your heart, values, and personal choices. Your goal is not simply to quit your addiction, but to make addiction impossible by replacing it with a path of your own design that is true to you. Knowing yourself, your strengths and passions as well as your vulnerabilities and areas of self-deception, is essential both for making on-the-spot decisions and for completing your long-term goals. Self-knowledge is the engine of free will; it allows you to understand your motivations and then to make decisions consciously and deliberately, with your purpose in mind. Addiction generates a massive blind spot, preventing you from seeing beyond its own immediate satisfaction. Whether or not you have been addicted to anything, you surely have witnessed the results of this blind spot in other people. Perhaps you have even expressed frustration and incredulity over their unwillingness to see what is so clear to everyone else: “Why doesn’t she leave him?” “What was he thinking when he did that?” “How could she leave her kids alone?” “Who does such a thing?” And, maybe you offer a concession to your own blind spot, “I have my moments, but I’d never go that far.” You probably wouldn’t go that far, and you know yourself well enough to make that assertion.

CASE: Liam is strikingly handsome—compelling in a rakish, movie-star kind of way. He is also a long-term alcoholic. His friends (of whom there are few) and acquaintances commonly refer to him as “a drunk”—if not worse. “Drunk” is a harsh term, but the images it conjures are apt for this person. Liam is, it seems to everyone, a lost cause. Insufferable and obnoxious, he blows the fuse on everyone’s last nerve and has been banned from almost every bar in town. He wears out his welcome almost instantly by telling racist and sexist jokes, making rude observations about other patrons, and—like the classic drunk—spilling his drinks and falling off his stool.

Although Liam seemingly has no limits and no restraint, there are two things he will not do no matter how impaired he is: He will not drive drunk, and he will not cheat on his girlfriend (surprisingly, Liam does indeed have a longtime girlfriend).

Liam’s personal taboos—few in number as they may be—are deeply ingrained in him. They spring from genuine values: his sense of loyalty to his companion and his unwillingness to chance hurting or killing someone. No matter how wasted he may be and no matter how many bridges he burns or people he offends, he is incapable of giving himself permission to cross those certain lines. The converse of Liam’s case is also true. Excusing poor behavior by blaming it on addiction is one of the ways that addiction blinds—or deludes—us. After reading Liam’s story, you might say, for instance, “Okay, so maybe I drive occasionally when I’m high, but I’d never tell a racist or sexist joke no matter how messed up I get.” If you had a similar thought, ask yourself this question: “How is it that, no matter how impaired I am, I will never do one thing, but can still find an excuse to do the other?” It’s really rather remarkable, when you think about it.

Consider, for example, someone who is prone to flying into rages. He’s unpredictable, and people walk on eggshells around him, never sure what will set him off or when he will throw a tantrum. When this guy loses it, he screams obscenities, slams doors, stomps around, menacing and invading others’ personal space. He might throw something across the room or turn over a piece of furniture or put his fist into the wall. When it’s all over with, he always feels ashamed of himself and excuses his behavior by saying that he was so angry that he lost control. If you were brave, you could ask him at this point, “If you’re so out of control, how come you haven’t killed anyone yet?” Think about it like this: even when this loose cannon is in a blind rage, he is always able to prevent himself from taking his behavior to the point of no return. From where does that self-control and will come?

This example and Liam’s case are both extreme and disturbing scenarios. I have included them here to demonstrate that everyone—no matter how far gone—has standards and lines they will not cross. The taboos they have established for themselves spring directly from their personal priorities. But the converse is also true. Say you do things that you feel violate your true value system as a result of your addiction, such as cheat on your partner while drunk, gamble away your children’s college fund, or skip work to play World of Warcraft. It’s a difficult pill to swallow—but you would not do these things if you did not give yourself permission to.

Self-knowledge is a lifelong process of discovery. Shedding light on your motivations requires you to bring your self-acceptance practice to bear on everything you learn about yourself. You might find that you have certain positive priorities that you always honor. Say, for instance, you haven’t yet quit smoking, but you never smoke in the house or in front of children. Or, although you have a serious drinking problem, you never drink too much while with your parents. Clearly, your commitment to your family is key and inviolable. But you may find that other values you hold dear are more easily shunted to the wayside—your own health, for instance.

To continue with the example of the smoker, let’s say there are a couple of value systems in conflict within you. Smoking provides you with some alone time, helps you focus on your work, and makes you feel productive. At the same time, you know that you’re putting your health at risk through your smoking and thereby endangering your family’s well-being. How do you reconcile this? When you allow yourself to see that you have a conflict of values, you are in a position to make some decisions, to act on your primary motivations. Rage-aholics who are able to control their behavior despite being consumed by anger seem to do so in unplanned ways. That is, they don’t deliberate about which acts of violence they will commit. They’re acting on autopilot. Self-knowledge allows you to shine light on the motivations behind these choices, hidden somewhere within you, so that you can make your decisions intentional ones.

Here are exercises and practices that will help you become more self-aware:

![]()

BE PRESENT: As I discussed in Chapter 4, we all experience moments of grace, in which we hear from our inner self. Rather than waiting for these moments to arise spontaneously, call them forth deliberately. Whenever it occurs to you—perhaps set a chime on your cell phone as a reminder a few times a day or choose a regular time every day, say, when you’re in the shower—to stop what you’re doing for a couple of minutes and bring your attention into the present moment and to all your senses. What are you doing at the moment? How is your posture? What is the quality of light in the room or outside? What are the objects that surround you? What do you hear? Smell? Do you have any aches or pains? What is your mood? You don’t have to write anything down. Just notice, and bring yourself as fully into the present as possible.

MOVE: If you are a physically active person, employ the same “Being present” exercise when you are engaged in an activity. Bring your full attention to your body’s movements. Alternately, find a physical activity that you are unfamiliar with—say, learn a new dance or take a yoga class—and as you’re learning new, awkward-feeling moves, take a moment to bring your attention to these unfamiliar physical sensations. If you are not physically active, carve out some time during your day to walk or stretch or swim. When you are engaged in the activity you choose, focus your awareness on your body and movements. If you are walking, for example, pay attention to your steps—how the ground feels under your feet, how your muscles feel when moving.

LISTEN: When you are engaged in a conversation with another person, practice intentional curiosity. Take the time to focus your attention on what your companion is saying and respond only with relevant questions or with acknowledgment that you have heard—put your own input and desire to express opinions on the back burner (remember motivational enhancement?). This is especially powerful when you converse with a child and focus on his or her mind and world. Do you notice any discomfort in forcing yourself to listen? If so, can you describe what that feels like? How does it feel to keep your opinions to yourself? Why do you think you experience this discomfort?

HOW DO OTHERS SEE YOU?: Choose three people in your life. They don’t all have to be close to you. You might choose your spouse, a close friend, your boss or employees, your neighbor, your roommate, your mother. In your Personal Journal, compose a picture of yourself through each of their eyes. Do you believe they see you accurately? Do different facets of your character present themselves depending on whom you’re with? Keep in mind that this is fine: It’s usual that you treat different people differently—like your spouse and your parent. If, for instance, you find yourself patient with one person but short and irritated with another, remember that these are simply facets of yourself. You are not being dishonest or fake just because you behave differently with different people. Self-acceptance (Chapter 5) is key here. On the other hand, when you bring this difference into mindful self-awareness, you might ask whether you want it to persist. Should you be as patient with one person with whom you are short-tempered as another with whom you display greater tolerance? This is a trait you obviously are capable of expressing—should you use it more readily?

WHAT ARE YOUR STRENGTHS AND VULNERABILITIES? In your journal, make a list of the areas of your life in which you excel or have excelled in the past. Then make a list of areas of your life where you feel vulnerable. If you have trouble making this list, ask for help from someone you trust. In fact, even if you don’t have trouble, you might benefit from doing this exercise with someone you trust. They may provide a more realistic, objective perspective on your answers. If you choose to do this exercise with a companion, note the areas of disagreement.

![]()

Shoving Off

The overarching goal of The PERFECT Program is to reach the point where you can lift your sails, free from addiction, and embark on your real life’s journey. The skills you have been learning will help you achieve the balance necessary to head off into the sunset, rather than to keep you moored to a program, a label, or a prescribed way of life—whether that be “addiction” or “recovery.” It’s time to take that step, like the tightrope walker Philippe Petit, depicted in the film Man on Wire, taking his first step onto the wire spanning the two World Trade Center towers. (Well, your step is not quite that daring.) After all the work you have done, it’s time to put what you’ve learned into play. Let’s start by navigating out of the rocky, sometimes perilous port you’ve been anchored in.

You have identified a vision for your life and have defined some goals—it’s time to take some decisive steps, make some real moves. In the previous chapters, you gathered and organized everything that is important to you, the things that bring value, purpose, and meaning to your life, and you made some decisions about where you need some life-management support and skills training. Now, you can bring these elements into present actions. You have thought about life changes you want to make: some monumental or frightening, like leaving a relationship or tackling your debts, and some more gentle and exciting, like starting a garden or going back to college. Regardless of whether your current goals are difficult or simple to activate, getting started—taking that first step off your secure mooring—can be daunting.

We have a tendency to think there is some magic moment in the future when we will be the person we think we should be. Everything must be right in some mystical, undefined way before we can fully exist, as if a square on the calendar held some transformative power: We’ll start on Monday. We’ll wait until after the holidays. We will wake up a completely different person on New Year’s Day. Of course, it can be helpful to pick a date to start making significant changes or to create a new project. If you find that works for you, by all means, get out your calendar and mark it off. At the same time, there is nothing stopping you from making smaller corrections to your course, based on the goals you have set for yourself, this day—this hour. You are here, now, and you can start right where you stand.

Begin by deciding and committing to what is immediately doable and essential—that is, what you can and want to introduce into your life today—and beginning to do so. (Exercising regularly, for instance, or doing yoga or meditating.) Next, you will focus on your long-term goals and what you need to do to achieve them. (Going to school, acquiring a new skill, forging intimate relationships with family members, friends, or people as yet unknown.) Finally, you will approach the monumental life changes you want to make and decide on some strategies for setting these in motion. (Moving, forming a partnership, getting divorced, having a child, changing careers.)

You have identified important goals you want to pursue and have decided how you want to approach overcoming your addiction in a way that works for you, based on your values and preferences and your exposure to the ways people overcome addiction, as described in Chapter 2 and throughout this book. Now let’s prioritize your necessary steps, starting with things to be addressed immediately—including, of course, your addiction. You may also need to deal quickly with concerns around your family, health, or work. One way to decide what to do now is to address the things that will create chaos if you wait any longer.

You may also want to start to do simple things that will enhance your quality of life—like keeping your residence clean and organized. Think of those things also that you’d like to adopt into your life, like exercise or other wholesome activities. In terms of larger goals, consider your education, career, and perhaps social and family life. And, finally, you may have some serious changes to make to your living situation that may require you to shore up your resources (both financial and emotional), to seek legal counsel, or to venture into territory that is overwhelmingly unfamiliar, such as striking out on your own for the first time. Use your Goals Worksheets to help guide you.

![]()

IMMEDIATE: In your PERFECT Journal, list the changes you intend to make now and describe the consequences for you if you do not. Consider how you will implement these changes—break them down into smaller steps and prioritize them. Then make a commitment to yourself by scheduling these things on your calendar. For instance, if you must see a dentist because you are in pain, commit to a time to make the phone call and set the appointment. Similarly, if you plan to go cold turkey on your addiction, commit to it on your calendar. If you are delinquent on your bills and risk being shut off or going to collections, contact your creditors. Get started now, and keep close track of whatever you do to further your goals. Do not forget to make note of how it makes you feel to tick these tasks off your list. If you find yourself overwhelmed by the number of tasks you have set for yourself, go back and reprioritize.

INTERMEDIATE: List in your PERFECT Journal those things you want to bring into your life, and begin setting a sensible schedule for implementing them. You may need to do some research to accomplish this. If so, schedule time for that work. As you did with your immediate plans, make commitments, follow through, and check off their accomplishment. Keep track of your activities and how it makes you feel to pursue these things. In your Personal Journal, if you find that you have lost interest, or that something you have included on your list doesn’t live up to your expectations, explore those feelings and ask yourself whether your plans were true to you, why you were wrong in thinking they were, or if there is another reason you have abandoned them.

MAJOR CHANGES: If you are experiencing impending or current major upheavals in your life, you may have a lot of planning to do and hard decisions to make. It could be that making a major change is imperative; it must take top priority and so also becomes an immediate need, albeit a potentially life-altering one. If you are in an abusive or destructive domestic situation or, say, your house is in foreclosure or you are in a serious legal bind, you must focus on this right away. In this case, you may need to find some community, therapeutic, or governmental resources to help you take control of your situation and prioritize the tasks required in order to make changes—or simply to cope with your situation. Use your goal-setting tools and begin taking the steps you need to take to see this through. Chapter 10, about triaging, provides you with lists of resources for difficult or unfamiliar situations.

If the major changes you’d like to make are less emergent—say, a long-coming divorce or a residential move, buying a house, having a child—you can begin to prepare yourself in less dramatic ways. Meanwhile, focus steadily on your addiction and wellness goals so that you are in a stronger position to navigate the inevitable frustrations and surprises that come with tackling your major life goals—put simply, you can’t have children or launch a new career while getting drunk daily or having other unaddressed psychological and health issues.

![]()

Getting Straight

In the early stages of leaving an addiction, you may have a lot to put in order—many things to remedy and take care of—before you can feel fairly secure in your recovery. The most prominent single finding from Baumeister’s research on willpower1 is that you develop that muscle—become capable of self-regulation—the more you practice it throughout your life.

Honoring your commitments

You may have to clear up quite a bit of baggage and debris following your emergence from addiction. After dropping a lot of balls and sacrificing much to your addiction, correcting your course is not about making up to particular individuals (see Chapter 5, on forgiveness), but about establishing yourself as a worthwhile, dependable person. Doing what you say you’re going to do creates a secure identity, both in your mind and the minds of others, and a feeling of having a firm place in your community and the world. Part of making and keeping legitimate commitments is being able to recognize when you are over-committing or making promises that you simply cannot keep just to maintain some peace in the moment or to make someone feel good. If you generally have trouble following through on your promises, here are a couple of approaches to enhancing this skill and value:

• Don’t make commitments impulsively, even if someone is pressing you for an answer or it sounds like fun. Take the time to see whether it will fit into your schedule, whether it is something you find important, or whether it will compromise other, more important commitments you have made.

• Practice making and keeping commitments in small ways. Start by, say, scheduling a task and doing it during the time you set for yourself. Find an event that interests you and commit yourself to attending.

Honoring your commitments to yourself is a major value to cultivate—an essential element of mindfulness, self-knowledge, and overall fulfillment.

Domestic space

Moving from your existential place in the world to the most physical space you occupy, having a living space that provides comfort and sanctuary will contribute greatly to your peace of mind. You must decide for yourself what that looks and feels like for you. That might entail putting your kitchen in order so that you can cook meals, or it might mean decluttering your entryway. You might like to have a home that could be featured in Better Homes and Gardens, but a more realistic and satisfying target for you may be to avoid a pile of dishes or food rotting in your sink and to sleep on clean sheets. You may be someone who can’t rest unless everything is in its place, or you may find that puttering around your house each morning completing small household tasks is calming. Whatever your inclination, start following through on it. Your Goals Worksheet enables you to identify key areas to focus on—begin there. Here are some ideas and resources that may help you get going:

Getting help and exploring resources: You may be in a position to hire a home organization expert or a cleaning service to come in and do a deep clean. Don’t be reluctant to do so because you’re embarrassed by whatever mess you have. They’ve seen it all. (Which I, as an addiction therapist, might also say—in case you need to consult someone like me.) You can also enlist a good friend to come in and help (as described in Chapter 7). Another option is to seek out a local co-op group, or start one yourself, of people who all meet at one member’s house on the weekend and work together to tackle the domestic chores.

Accountability: Free online resources can provide you with accountability and direction. Here are some websites that you might find useful: Flylady. net is a coaching resource that helps you prioritize your household tasks. Rememberthemilk.com is a task manager, which you can use online or as an app for your phone. Do some exploring; see if you can find other resources with a built-in community of people who are working toward the same goal.

Social Skills: Creating Community and Intimacy

Community

Our communities consist of our families, living mates, neighbors, social networks, co-workers, activity partners, church congregations, towns and cities. Nothing enhances our sense of purpose, of belonging on earth, of meaning, of contentment more than does feeling part of a community. This is fundamental to the human condition, and the general loss of community in modern culture is a severe blow to all our humanity—as well as being a major cause of addiction. Addicted people tend to form pseudo-communities around their addictions (think again of Rose in Chapter 1), and often their fear of losing that pseudo-community is a strong component in maintaining an addiction. That is, people fear they will be lonely if they are deprived of their addiction mates. Conversely, forming positive communities is a strong antidote to addiction and is even used as a form of treatment, social network therapy, as described in Chapter 7. Reconnecting with such non-addiction-focused, real-world groups in meaningful ways will bring you a deeper and more satisfying sense of belonging than addiction ever can.

![]()

EXERCISE: In your journal, compose a list of the communities you are involved in or touch upon. Acknowledge your connections to the world. Make another list of some others you would like to be part of. Depending on your personality, you may want to limit yourself pretty much to family or a close social circle, and your neighborhood; or you may want to involve yourself in a number of different areas involving special interests you have or want to pursue. Imagine how you would participate in these groups, and then ask yourself if it is realistic to make the commitment. Complete a Goals Worksheet to help you prioritize and decide what steps to take to find and join such communities.

![]()

Making friends

Joining communities has much in common with making friends—finding compatible and accessible people with whom to spend time, share interests, and perhaps develop deeper feelings and relationships—up to and including love. People—as we discussed in the last chapter—have different degrees of sociability, of skill at and tolerance for interacting with others, of enjoying time alone. But it’s fair to say that everybody needs some degree of skill at both being alone and being with others. A free life can’t be lived without some version of both traits. If you can never be alone, then you can never be at ease and must always desperately seek out contact—for better or for worse (see the case below). If you can’t spend some time with and interact with people, then you can be shut into yourself—sentenced to aloneness that is a kind of addiction.

The short answer to how to be able to live both parts of yourself is—as with nearly everything in this book—practice. Schedule time to spend by yourself—something you must, of course, do when you are meditating. Reading, listening to music, walking, being with a pet—all of those do count (the PERFECT Program is very open-minded). Watching television counts if you do it purposefully, because you are specifically watching something you enjoy for reasons you know. And schedule time to interact with others. This may mean going to one of the groups you described in the previous section. Or it may mean calling and speaking with, or arranging to visit or meet, an old friend, a relation, or someone you’d like to get to know—for any reason whatsoever. It is a mark of our times—and it is not a good mark—that actual contact with people, even so much as talking by phone, is becoming a relic of the past. Nothing against e-mails and iPads, but we can’t do without human contact.

CASE: Isaac had been a good student. But when he arrived at his large, well-regarded high school, he suddenly seemed intimidated. And so, for most of his first semester, he walked around the school as though he were in a penitentiary. Of course, Isaac’s parents—Rachel and Bob—were worried. And, so, when he returned home one day with a smile and said he had lunch with a few kids, one of whom he liked especially, his parents were glad.

But it turned out that this outsider’s group was heavily immersed in drugs. Thus followed four years of hell for Isaac’s parents, ending when they used a large part of their life savings to send Isaac to a residential treatment program. The program seemed like a good one, although Rachel and Bob questioned some aspects of it. Was it really true that Isaac had inherited a disease and that he could never drink (let alone take drugs) for the rest of his life? After all, he was only nineteen. Moreover, when he graduated the three-month program, he was sent to a residence. But in many ways the kids in this group were a lot like those he was with in high school, only now supposedly recovering.

But what most worried Rachel and Bob was that, as they kept up with the parents of the other kids they met in treatment and the group home, nearly all of their children had relapsed. How is that possible, Bob asked Rachel, after they learned so much and did so well interacting with one another in treatment and the halfway house? What had occurred, of course, is that they had simply fit in again with their substance-abusing peer groups as soon as they returned home.

The crucial issue at every point in Isaac’s story is how easily he formed relationships, with whom he did so, and in what direction the friends he made pulled him. Isaac’s story is about the centrality of friendship formation and dealing with others in addiction and recovery. Learning social skills like those in the previous chapter in order to meet diverse and healthy individuals is an essential element of an addiction-free life.

Intimacy, love, and addiction

Love is one of those large goals that an awful lot of people pursue—and that an awful lot attain in one or more forms (including spouses, friends, and children). But it’s no sure thing, and—depending on how far you are starting behind in your life—it may take you some time to acquire and assemble these resources. They then become the building blocks outlined in this chapter and the rest of Recover! for forming truly satisfying relationships. This is because love—as Archie Brodsky and I indicated in Love and Addiction—is built on the exact opposite foundation from an addiction. Addiction stems from the absence of connections to life and substitutes for such connections. Love flourishes best when you have the most points of contact with the world, including other positive relationships. Addictive love relationships are most likely when you are desperately seeking emotional sustenance from other people while you haven’t yet created the necessary basis for sharing such intense feelings by having a solid life in place.

Practical Skills: Education, Work, Financial

Education and work

Don’t assume that you have ruined the connections you have to every part of your life and every person in it because of your addiction. You may have hurt them but, often, many can still be rescued. I have offered several case studies of people who are successful at their jobs despite their addiction (of course, other areas of their lives suffer). So don’t reject—in anticipation of being rejected—any parts of your life that have survived your addiction even as you work to improve them. For example, if you haven’t been fired, don’t quit your job out of guilt.

However, for many, keeping a job or pursuing an education has fallen by the wayside. If you’re in that category, you may be wondering where to start—and completing your Goals Worksheet leaves you feeling lost. How do you set realistic goals for yourself when you feel so far behind or so far out of your element that you can’t even be sure what your real options are? Do you know how to look for and apply for a job, what courses to take at school, how you will pay for these courses, or what degree suits you best?

CASE: Thomas had been smoking pot regularly for so long that all he could do was sell the drug to others as a way of getting by. He had once been a quite capable computer programmer. But he was long past the point of feeling up-to-date with writing code, the Internet, and information technology skills. Whenever he considered quitting smoking grass, he was confronted with the enormity of the barriers separating him from the real work world. How could he begin to reengage?

Of course, Thomas had once been able to obtain jobs in information technology. As always, getting started—or restarted—is intimidating. You may imagine the barriers as higher than they are. In any case, there is no alternative other than to begin. Thomas began taking online courses, which are readily available and accessible. As he settled into doing course exercises, he saw that his old skills were still relevant; he even compared favorably with others taking the courses, according to the published grade curves. In a short time, he was applying for jobs (albeit having to fashion crafty explanations for the gaps in his resume—fortunately, he had never been arrested). The process wasn’t dramatic, and Thomas wasn’t where he would have been if he hadn’t devoted several years to his drug of choice. But, then, life is a process, always beginning with now.

For specific practical suggestions for continuing or resuming your education, getting a better job, or starting a business, see Chapter 10, “Triage.”

Financial

Money management can be enormously stressful, especially for those in the throes of an addiction who have allowed bills to pile up or who are avoiding calls from creditors or the IRS. Addictions are expensive habits that lead you to spend money you don’t have—especially if your addiction is gambling or shopping. Of course, the cost of liquor or cigarettes or street drugs also adds up, as does that for virtually every addiction. You may know about waking up in a panic over money in the middle of the night.

But no matter how painful it is to contemplate, this is an area you simply must get under control, because it will weigh you down until you do. Dealing with finances can be an unappetizing task if you are in debt or behind on your bills. As anxious as dealing with your finances makes you, however, worrying about your money when you don’t have a handle on it is far worse. It is imperative that you know where your ground zero is. In this as in other areas of your life, you are able to address and fix only what you are able to see clearly.

So let’s tackle finances and restore your peace of mind. Whatever the mess you have on your hands involves, you can pull yourself out of it and keep yourself out. Schedule time on your calendar to devote to this. When that time comes, shut off your phone, iPad, and so on, and then break this task down into a series of manageable mini-goals such as those outlined in Chapter 10, “Triage.” It’s possible that you will have to explore bankruptcy. That’s a big topic for which this book is not the right source of advice. But be aware of it as a possibility.

Personal Skills: Your Health and Well-Being

Self-care

Since addiction can cause you to disregard so many aspects of your life, your ability to care for yourself diligently may also have suffered. Personal hygiene is not just something you do to make yourself presentable to the world; it is something you do for you. Showering and brushing your teeth regularly, sleeping and eating well, getting dressed every morning, exercising, visiting the doctor, washing your clothes—all are absolutely important. First, they foster a sense of self-respect and energy and help you develop wholesome habits. They engage you in acts of self-nurturance, which you deserve. They signal that you are ready to participate in your own life. If you have slacked off on your self-care practices, ask yourself how, and begin bringing these good habits back into your life.

Leisure pursuits

Since addiction takes up so much time and energy, you may have some time on your hands. Boredom, restlessness, aimlessness, and obsessive, intrusive thoughts can be powerful instigators of relapse, and not knowing what to do with yourself can be emotionally and morally excruciating. Do you remember a time in your life—most likely in your childhood—when you could lose yourself in play and creativity? Perhaps you—alone or with friends—were able to invent an elaborate pretend world, characters, and scenarios that kept you engrossed all day long! Recapturing this part of your life—your creativity and sense of pure, free fun—is as important to your life as it is for you to start bringing order to the chaos. When you have such a sense of joy, everything—reading, walking and hiking, seeing people, being alone—can open up to you. Pull out your Goals Worksheet and fill it in with activities that will spark your interests, sense of play, and feelings of accomplishment. You might include art, volunteering, spending time with your children or grandchildren, cooking, exercising, learning a new skill, taking a class, and on and on.

Spiritual or humanitarian

If you practice a particular belief system or religion, or if you honor your place in the grand scheme of things as a member of the human race, consider giving your spiritual or belief system or humanitarian impulses a bigger place in your life. This investment will contribute greatly to your sense of purpose and community, infusing your life and actions with meaning. You may seek out a congregation that feels like a good fit for you, join a meditation group, or volunteer for a cause that you support, with the intention of building community around this important area of your life. Doing so—especially if you lack family or community support—will broaden your scope and give you a comforting sense of your place in the world.

Mental health

As you begin to drill down into the areas of your life that need attention, you may become aware of underlying mental health issues. Perhaps you have already been diagnosed as having—or believe that you may have—bipolar disorder, anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, or some other type of psychiatric condition or disorder. Not to minimize these disorders, it is safe to say that we all have some experience of them and other emotional conditions and trauma. As I described in Chapter 2 on addiction and recovery, emotional problems are both causes of and responses to addiction, while at the same time they are important issues for recovery. The good news is that many of the techniques and practices you are learning in The PERFECT Program are equally useful for combating these emotional problems or disorders. So, feelings that you’ve been masking with addiction may emerge in full force, but you are also developing positive and powerful ways of coping with them.

However, just as with the case of seeking bankruptcy relief, there are matters that go beyond the scope of Recover!’s aims. If you need help with serious emotional problems that haunt your ability not only to escape addiction, but also to live fruitfully, you should seek professional help. My approach is obviously consistent with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and pragmatically oriented counseling, and so I favor that type of treatment. In America today, it is hard to find such help in psychiatry, which is dominated by pharmaceutical treatments. Recover! and The PERFECT Program don’t generally go well with drug treatments, although they don’t rule them out or disparage them—as long as the medications are combined with counseling. Of course, the quality of the counseling remains a critical issue, and receiving good—or even safe—treatment is by no means guaranteed. In HMOs and other institutional care settings, the psychiatrist prescribes drugs while a psychologist or social worker provides CBT or supportive therapy. Sometimes—too often—supportive therapy simply permits venting that enables people’s complaining and blaming others. Psychiatrists, meanwhile, are becoming less able—both by training and due to economic constraints—to practice any kind of psychotherapy.

Where therapy is provided—whether by a psychologist, social worker, or other trained counselor or, occasionally, a psychiatrist—the favored type is now CBT on the grounds that it addresses your problems directly and has been shown to be effective. Psychoanalytically oriented (“talk”) therapy, on the other hand, is increasingly difficult to find or be reimbursed for. Feel free to explain what your perspective is and what you seek in exploring and entering any type of mental health relationship.2 And there is no way for you to eliminate your own critical decision making in deciding whether your therapy is being helpful.

Reframing Failure

Once you start taking deliberate steps to make things happen in your life and develop healthier habits of mind and action, you will certainly find yourself missing the mark on some of the goals you have set for yourself. In times like this, you might recall Woody Allen’s famous dictum: “Ninety percent of life is just showing up.” To put this in the context of The PERFECT Program: “showing up” means that your conscious presence and awareness is your success. Your engaged participation is all that’s required, even if the results don’t always measure up. You are now using the skills you’ve learned in the task of making broad and permanent changes in your life. But the key changes cannot be measured by how flawlessly you succeed at the things you set out to do. What’s important is that you made the decision to do them and pursued your goals mindfully—that is, intentionally, investing yourself in the process and keeping track of the results. What you’re now doing is living your life.

Incorporating the essential elements of your true self into your life is an exercise of your free will, which may have wilted from neglect. You are training your true self to take over for your addicted self, which will, ultimately, make addiction irrelevant. Developing any weak muscle can be painful and make you hyper-aware of the strength of your addiction. Imagine, for example, trying to write clearly and automatically with your non-dominant, or “wrong,” hand. The resulting awkwardness and sloppiness shout out to you that you could so easily switch back and just get it over with, resorting to the muscles (or habits) you relied on before. Embarking on your recovery process will bring similar moments of awkwardness and distress. You will feel tempted to resume familiar but destructive habits when you fail at your new efforts. Whether you do or you don’t, you may judge yourself harshly. This self-punishment may feel correct, but ultimately it blocks your forward motion.

For example, say that one of your modest changes was to bring a new plant into your house, to give your environment a sense of vibrancy. But then your plant died because you didn’t water or fertilize it properly. Your reaction might be brutal self-recrimination: “I am such a loser; I can’t even keep a plant alive. What’s wrong with me?!” But it’s just going to happen sometimes that your best intentions won’t pan out. While recognizing this, you needn’t allow yourself to accept failure. Plan for failure and learn to reframe it with compassion: This is not failure; it’s information. You’ll do better the next time. Either that, or you’re just not a plant person.

When you reframe failure as information (or feedback), you maintain your sense of active engagement, control, and forward movement. If you walk into the gym for the first time and try to match the resistance the last person set on a machine, you probably will be unable to lift it. This could be embarrassing if anyone were looking (although no one is), but in any case it’s not the end of the world. You don’t leave the gym or give up or throw a tantrum (now that people would notice). You simply get real about your abilities, adjust the weights accordingly, rest a bit, and then begin to become stronger gradually and sensibly. Similarly, if you make an attempt at something life-affirming and find that you are unable to see it through, take the opportunity to gather information about your blind spots and your unreal expectations. But always remain mindful of the purpose behind your attempt.

![]()

EXERCISE: In your Personal Journal, think of a recent failure and write about it: What were you trying to accomplish? What went wrong? What do you think this says about you? Now, try to look at the scenario more objectively and compassionately: Were you trying to do something that requires habits not yet in your repertoire? Were you attempting to take on more responsibility than you could reasonably handle or fit into your schedule? Did you start at a place that turned out to be over your depth? Were there steps you missed? Situations you avoided? If so, why? If you were allowed a do-over, would you try this again? If not, why not? And if so, what would you do differently?

![]()

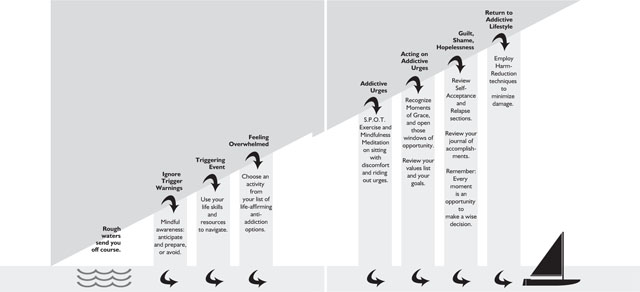

Detour: Relapse!

Speaking of reframing failure, the subject of relapse is surely on your mind. It is not inevitable, but it happens. You can prepare for it both by anticipating and avoiding it and by developing techniques for righting your course after it happens. Relapse is a return to addictive behavior—a backslide—which occurs after a period of progress. The impact of relapse can be very demoralizing, making you feel as if you were back at square one, or a hopeless case. What causes it? How does it happen and why?

Alan Marlatt began his research on relapse prevention by investigating what caused smokers, alcoholics, and heroin addicts to relapse.3 The standard interpretations were that (1) their withdrawal symptoms simply overcame them, or (2) in a conditioned response, people were exposed to stimuli associated with their former use, and this association created irresistible cravings to use.4 But when Marlatt actually questioned addicts, he found that they were unlikely to relapse when experiencing intense physical urges to use, as occur during the immediate withdrawal period. Rather, relapses were responses to negative emotions and conflicts that the study subjects previously may have used their addiction to address and that exceeded their abilities to manage without their addiction. Or else they relapsed when they entered a setting where they had used or were with people they had used with before.

Based on these findings, Marlatt developed relapse prevention techniques to supplement environmental planning—that is, staying away from “bad” places, people, and things. Relapse prevention focuses on people’s coping mechanisms for dealing with stress (or even pleasure) in general, and specifically for addressing cravings to use that appear either randomly or in challenging emotional situations. Himself a longtime practitioner of meditation (to which he credited his remission from hypertension), Marlatt was moved to see whether and how meditation could be part of the cornucopia of techniques for combating relapse, including cravings. The results led in the direction we have picked up from Marlatt and other researchers and adapted and expanded for The PERFECT Program.5 Marlatt’s work has always had a sound scientific basis. The value added through The PERFECT Program is to develop and tailor these techniques in ways that are personally and clinically useful, since Alan himself never wrote any popular guides for people to follow.

Simply put, a relapse is triggered by imbalance. The situation at hand or the triggering event overwhelms your ability to cope while you are developing new skills, resources, and perspectives. Recalling the “dominant hand” analogy, in which your dominant hand represents your ingrained habits, imagine that you are diligently practicing handling all your daily tasks with your weaker hand. Despite the awkwardness, you are becoming more adept all the time. But one day, without warning, someone pitches a ball directly at your head. You instinctively reach out to grab the ball with your dominant hand.* That is just about how relapse works, and there are several scenarios and life events that might trigger it:

• Major or milestone events

• Strong emotions, including anger and even joy

• Unexpectedly powerful triggers that seem to arise out of the blue

• Loneliness, boredom, anxiety, restlessness, hopelessness, or any other painful or difficult feelings

• Being around people who undermine your goals

• Romanticized memories of the benefits of using, while forgetting or downplaying the consequences

• Unaddressed mental health concerns, such as depression, that require attention.

Can you think of other relapse triggers?

![]()

EXERCISE: In your PERFECT Journal, in the “Triggers” section (page 155), write down any situations that might trigger a relapse—or that have in the past. Can you identify exactly how your skills, resources, and perspective were outmatched by the situation? What action could you have taken to prevent the relapse? Or what could you have done/do to get yourself back on track?

![]()

Reframing relapse

As in our discussion of failure, a relapse can provide you with a wealth of information you can use to continue down your path to wellness. If you experience a relapse, use it as an opportunity to increase your self-knowledge. Make note of everything that led up to it: your life circumstances, the triggers you experienced, the self-deception that you now recognize. You should ask yourself how you can avoid or improve the circumstances leading to relapse, or whether you ignored feelings welling up in you that signaled where you were heading. Did your decision to indulge make you feel as if you were doing something good for yourself, like loosening a noose around your neck? What benefit, exactly, were you seeking? What in your life represents the noose? Are there parts of your life that you have been ignoring while seeking to improve other areas? If so, what changes can you make in your situation that will relieve some of the burden you feel?

You are now engaged in truth seeking about your addiction—where, when, and why it arises. Do your best to discover the truth. This is actually step one of mindfulness practice, recognizing and responding to cravings and other urges to resort to addictive behavior. If you have not yet been able to incorporate your mindfulness practice into your daily schedule, now is the time to make it a priority. Turn back to Chapter 4 to review your meditation and other techniques. This is a skill that will serve you enormously in relapse prevention, because it allows you to recognize and to ride out—or to recuperate from—uncomfortable feelings, like cravings, with the knowledge that they will pass. The practice of mindfulness will also expand your horizons, allowing you to identify the range of your options. Where before you might not have realized you had any choices, you now know there are a host of responses to insert between your urges and your addiction. Finally, continuing to exercise mindfulness in relapse prevention develops your ability to turn your attention where you choose to, away from triggers.

The central concept to keep in mind where relapse is concerned is that it is not failure. This means that, if you relapse, you aren’t “starting over.” In fact, “starting over” has no real meaning. Twelve-step programs make a virtue of “time.” Members count their days—even hours and minutes—of “sobriety.” They require people to start their count over if they have a relapse. So, if you have been “sober” for five years and then have a beer one day, you’re back at day one. I would say this was silly if it weren’t so destructive. Please recall my discussion of “hitting bottom” in Chapter 4. Go beyond this superstitious, irrational way of thinking, one that has created such ineffective approaches to recovery.

Getting back on track

Believing that you have completely and irreparably botched recovery is an example of the all-or-nothing perfectionist thinking that underlies addiction. It is clearly lacking in self-compassion. You always, always have the option to gather yourself and continue on your path. This is as open to you as—in fact, it is more common than—the AA-endorsed view that you have to throw in the towel. Even considering the latter as a possibility is wrong. At this point, you have the understanding, skills, resources, and perspective to make a conscious decision to continue on your path with mindfulness and self-regard. Remember Renee from Chapter 3, who, after six years’ abstinence from alcohol, went into a bar, drank, got intoxicated, drove drunk, and lost her license, her job, and her husband? All of that was unnecessary. Even so, she quickly righted herself and didn’t return to a life of drinking. By that point, recovery remained for her—despite her bad decisions and choices—the most relevant, easily accessed option in life.

![]()

Exercise: Relapse Moments of Truth

At times, you may be tempted to return to your addiction, when you have cravings—even compulsions—to use, say, when you are in an environment where you previously used, when you are vulnerable emotionally, when life has thrown you a number of challenges and defeats, or even sometimes triumphs and successes! How you deal with these moments determines your ability to navigate your recovery. Answer these questions in your PERFECT Journal:

1. Describe three situations in which you are most likely to use.

2. Visualize each situation and describe your feelings in it.

3. Describe a strategy for each that you can rely on instead of using.

4. Who would you call if you were thinking about using but wanted to resist? Why?

5. Who would you call if you had been using but wanted to avoid further damage? Why?

Should you discuss these roles with those individuals right away?

![]()

I have emphasized the idea that every moment is an opportunity to make a good decision. In other words, just because you have taken a single step in the direction of a steep cliff, it doesn’t mean that you are now required to take a running leap off the edge. This image opposes the 12-step or hijacked-brain notion that your misstep has propelled you off the cliff and your relapse is, like gravity, an irresistible force of nature. Relapsing after using is not like gravity. Your mindfulness skills will help you identify your moments of grace and give you the presence of mind to act on them at any point after the moment you veer off course so as to realign yourself with your values.

CASE: Martha, who has been battling an addiction to prescription painkillers, has recently decided to go cold turkey. She’s had some difficult moments, but has been able to stay on track by keeping her focus on creating order out of chaos. That has brought her a great sense of fulfillment and peace of mind. One day, as she was in the middle of cleaning a hallway closet that she had been using to stow all sorts of unusable junk, she was overcome by a seemingly random urge to stop what she was doing and visit a friend of hers who kept a well-stocked pharmacy in her pocketbook. Almost as soon as the thought crossed her mind, Martha jumped up and called her friend (“I’m so sick of sorting all this junk! I’ve been good for a month already!”), who was more than happy to accommodate her. Martha threw on a pair of jeans, drove to her friend’s house, plunked herself down on the couch, and swallowed the pills offered to her with a freshly opened beer. (Remember that, besides this being a relapse, it is also always dangerous to combine painkillers with other drugs or alcohol.) The two of them spent the night watching reality shows and giggling senselessly, and everything seemed to fall back into place.

The next morning, Martha woke up feeling terrible—and the self-recrimination was worse than the hangover.

What happened? At what point did Martha lose her perspective? It was as if a tornado picked her up out of the blue, right out of the messy closet, and plunked her down on her friend’s couch with a couple of pills in one hand and a beer in the other. And what now? How does she handle the cravings and old habits?

What happened? Martha’s “dominant hand” simply asserted itself and began to function on auto-pilot, as it will do. Habits, well-established patterns of thought and behavior, can take over in moments of vulnerability—this cannot be avoided all the time. Remember that as you progress, these moments will become fewer and farther between. But you may encounter them quite often at the outset. The key is not to pretend that you can—or should—evade them every time, but to recognize that you’re off course and take steps to correct.

Consider how many opportunities Martha has to avoid full-blown relapse and to realign her actions with her values. Perhaps, at this early stage in her journey, she wasn’t able to correct course as soon as she would have liked to. Blindsided by an urge whose momentum she couldn’t fight, she ended up on a trajectory that led her to a familiar, painful place. She may remember that this overwhelming urge hit her when she was sorting through some items that brought back painful memories or reminded her of a time when she was enjoying the situations that led to her addiction. Or, perhaps, she was overcome by the tedium of the task, or she was berating herself for letting things get so out of control. Or, perhaps, she was even thinking how great she was doing in her new life!

Navigating Relapse

At any time, before or after you veer off your course, you can tack back to your true path by using the skills, practices, knowledge, and exercises you have learned through The PERFECT Program.

No matter how far off you go, there is always a way back.

The PERFECT Program tacks back to your true course.

At the moment she wakes up, overcome with regret, she has a choice: to give up on herself or to forgive herself, take an honest look at what happened, and make some decisions. There is always a window of opportunity, allowing you to correct course, no matter how far down the wrong path you have gone, as Figure 8.1 shows.

Remember these things about relapse:

• Relapse is not failure; it’s information.

• Relapse does not mean starting over from scratch.

• Relapse does not mean that you will never recover.

• Relapse can be reversed at any stage—you do not have to pursue it to “rock bottom.”

You have the skills to realign yourself and continue with your recovery.

Avoiding relapse for love, eating, and other non-abstinent addictions

Some activities that some people find addictive, as I discussed in Chapter 3, can never be completely avoided. How can addicts avoid relapse when, in a sense, they have never stopped doing the activity? Think of eating. You will continue to eat on a weight-loss program. You may carefully avoid some foods, maintain your weight, and support weight loss with exercise. But you will not always follow your diet perfectly; no one can, and to attempt perfection—as always—can cause problems, in this case the sister addictions of obesity (i.e., bulimia and anorexia).

And, so, what happens when you as a dieter—say, one who has lost a considerable amount of weight—eats pasta or bread, or a cookie or some other sweet, that you have been rigorously avoiding? Indeed, how you handle these events is a mark of the success of your recovery. Say you have some pie or pasta. You will want to have a reasonable portion, which you can define differently according to the situation or where you feel you are in your recovery. Being able to eat these foods mindfully,6 both enjoyably and carefully, provides you with sufficient rewards that you no longer crave them as “forbidden fruits.”

At the same time, you—while eating the food—will be mindful that this is the kind of food that has hurt you in the past and that you cannot start indulging in the way you used to. You might surface an image of your former self eating this dish indiscriminately—even imagining yourself at your former weight. And it is summoning such images, with the commitment not to return to the misery, unhealthiness, and fear they inspire, that is the best guarantee that you will limit potential eating binges. Of course, to regain all of a considerable amount of lost weight is the result of more than one—more than several—such episodes. To return to your former weight would require you to altogether abandon your new lifestyle and way of eating, and the rewards your fitness and appearance have given you, in favor of those fleeting rewards provided by sweets, carbohydrates, and other comfort foods and snacks. You just don’t relapse in an instant; doing so means that you have reversed the entire recovery journey you have been on for months and years.

Balance

Getting started on your life’s journey with a sense of perspective—informed by mindfulness, self-awareness, and compassion; your values, mission, goals, and your skills and resources—is a monumental step. Knowing who you are, where you want to go, what you want to accomplish, how you’re going to accomplish it, and how you will stay focused on the path you have created for yourself, while skillfully navigating all the bumps in the road—like failure and relapse—is a lifelong process. It’s essentially what life is all about. It’s the very foundation of wisdom. To keep moving forward on your journey requires an ability to keep your attention constantly on your path. But it also requires your ability to return your attention to your path when you have lost track. Your mindfulness practice will strengthen your ability to return your focus to where it belongs, and your self-acceptance will give you the perspective and balance that allow you to do so.

Moving Forward

Launching your recovery and leaving addiction behind is not a bed of roses—you will encounter troubling moments that expose your vulnerabilities. But the odds favor your moving forward, and this chapter has helped you find the frame of mind—along with the techniques—to make sure this will happen. Balance is key. But maintaining balance requires strength and movement. These will develop as you continue on your path, learning to keep your perspective when things go wrong. You are on your way! Fully experiencing the non-addictive rewards you are finding will make clear your preference for this new life. Your decision to embark on this path is something to acknowledge and focus on; it is sufficiently important that the next chapter is devoted to celebrating your accomplishments, as well as all of the rediscovered facets of your life that bring you satisfaction, meaning, and joy.

![]()

*All analogies are inexact, and the “handedness” example is so because, unlike addiction, handedness, in most cases, is largely determined in the brain and is inborn. This example has the added disadvantage that there is a history of bias against left-handers that has sometimes taken the form of forcing them to use their right hand (I write with my left hand). The ball-catching example is the better example of learned handedness than writing, since most kids learn to catch best with the hand on which they wear their glove—the opposite hand from the one with which they throw a ball, not because that hand is especially adept at catching.