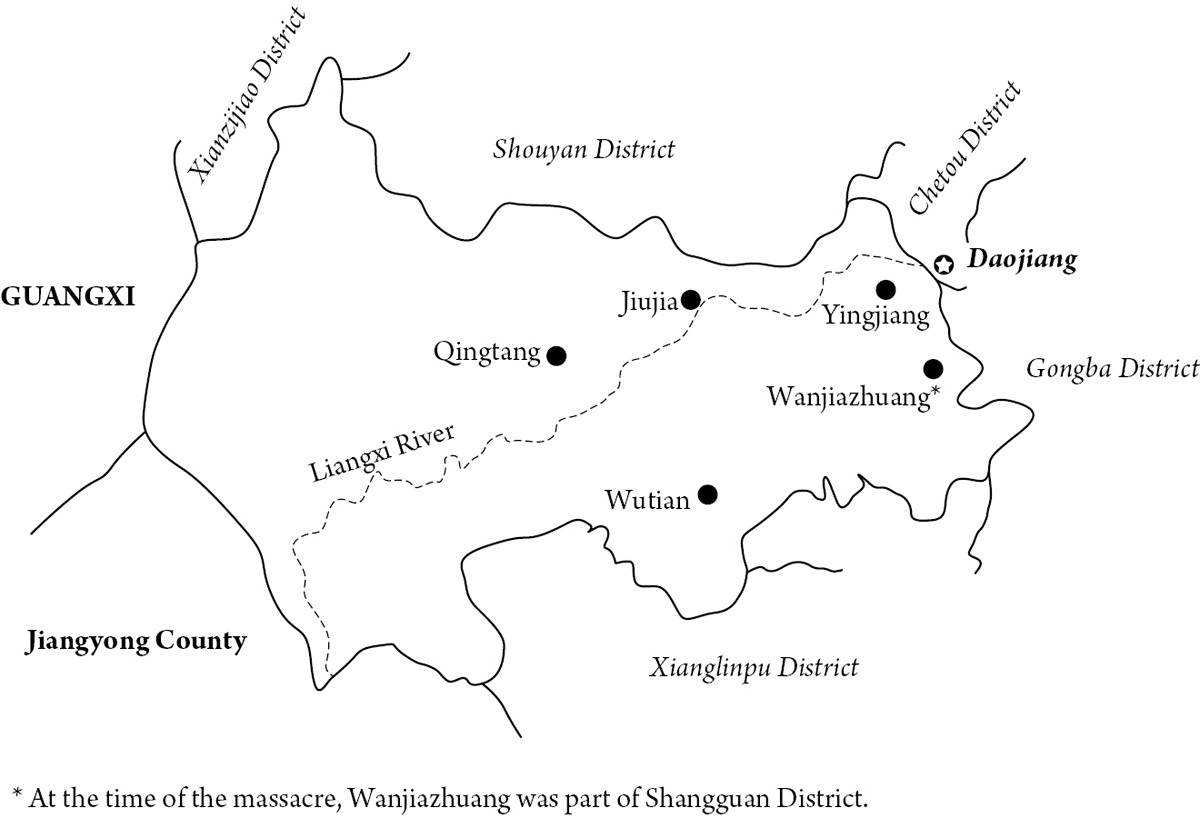

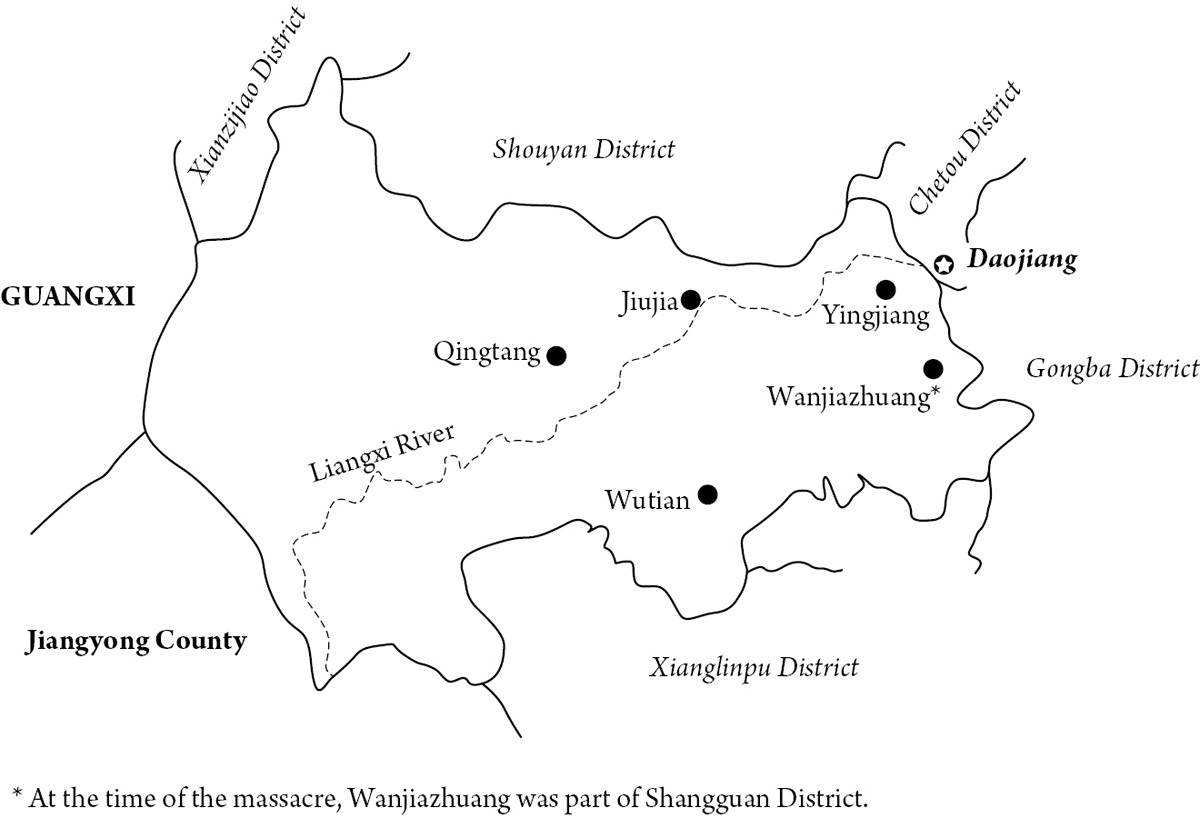

Map 3 Communes of Qingtang (Yueyan) District

In 1967, Daoxian’s administrative area was divided into ten districts, one commune (Yingjiang), and one town (Daojiang), but in 1984 it was reorganized into eight districts and the town of Daojiang. The following chart summarizes these changes:

Daoxian’s districts during the Cultural Revolution and after reorganization

| District Number | Name | Post-1984 Name |

| District 1 | Shangguan | eliminated; reorganized under Meihua, Qingxi, and Qingtang |

| District 2 | Chetou | Meihua |

| District 4 | Qiaotou | eliminated; reorganized under Xianzijiao and Shouyan |

| District 5 | Xianzijiao | Xianzijiao |

| District 6 | Yueyan | Qingtang |

| District 7 | Xianglinpu | Xianglinpu |

| District 8 | Simaqiao | Simaqiao |

| District 9 | Qingxi | Qingxi |

| District 10 | Gongba | Gongba |

| District 11 | Shouyan | Shouyan |

| Yingjiang Commune | put under Qingtang District | |

| Daojiang Town | Daojiang Town |

Only Gongba remained essentially unchanged. The complications that these administrative changes caused to the subsequent aftermath work will be described elsewhere in this book.1

The Task Force ascertained that killings were planned and arranged at the district level in eight (72 percent) of Daoxian’s districts: Shangguan, Qiaotou, Qingtang (Yueyan), Xianglinpu, Gongba, Qingxi, Meihua (Chetou), and Shouyan (the exceptions were Xianzijiao and Simaqiao), while killings were arranged at the commune level in 18 (48.6 percent) of the county’s communes. Killings occurred in 485 (93.4 percent) of the county’s production brigades. Among these, 27 brigades had 30 or more killings, 7 brigades had 40 or more killings, and 4 brigades had 50 or more killings (Appendix I provides a more detailed breakdown).

The main portion of Qingtang District (see Map 3) was known as Yueyan District in 1967. It was the district where the commander of the Red Alliance’s Yingjiang Frontline Command Post, Zheng Youzhi, served as People’s Armed Forces Department (PAFD) commander, and it was the first place where a district-level meeting was called to mobilize manpower for the killings. By the time of the Task Force investigation, the district’s original three communes, Qingtang, Jiujia, and Wutian, had been increased to include Yingjiang and Wanjiazhuang Communes. Those five communes accounted for 269 killings.

Qingtang District is located in the western region of Daoxian, less than 10 kilometers from the county seat, Daojiang. The Lianxi River originates within its borders, and Hunan’s second-highest peak, Jiucailing, rises from the Dupangling mountain range in the district’s western portion. Below Dupangling lies the limestone cavern that gave the district its original name, Yueyan, meaning Moon Rock, named for light patterns resembling the different phases of the moon that are cast into the cavern by an opening in its roof.

Map 3 Communes of Qingtang (Yueyan) District

A distance of 4 kilometers west of Moon Rock lies Loutian Village, the native place of Zhou Dunyi, one of China’s greatest philosophers and originator of the idealist school of Confucianism, who lived in the 11th century during the Northern Song dynasty. When we visited Qingtang District, we made a point of starting with Loutian Village.

At the time of our visit, Loutian had still not fully recovered from the catastrophe of the Cultural Revolution, and scars from the political campaign to “smash the four olds” were apparent everywhere. The ancient village was still breathtakingly beautiful, with its misty mountains and a crystalline rivulet where Zhou Dunyi was said to have experienced enlightenment while fishing. But the philosopher’s stone image had been smashed to pieces, and there was hardly anyone left in the village who understood the “dispositional reasoning” of the cosmic philosophy he had founded.

While in Loutian, we interviewed a 25th-generation descendant of Zhou Dunyi named Zhou Minji. He was 68 years old at the time and was the village’s former Chinese Communist Party (CCP) secretary. As a young man during the Japanese occupation in 1944, he had survived the shocking Loutian Massacre, during which Japanese troops killed more than 400 villagers hiding in a cave. Twenty-three years later, he became one of the killers in the Daoxian massacre:

After Liberation, I took up my work with an intense feeling of class and national vengeance. Eventually I joined the party and became party secretary of my production brigade. While I was secretary, I did a lot of good things for the masses, but also quite a lot of foolish and wicked things… . But I never acted against my conscience until that incident during the Cultural Revolution, which filled me with remorse. At that time, I was too fanatical to tell true from false, and I believed the lies others told, thinking that landlords and rich peasants really were organizing “black killing squads” to kill us party members and cadres. At the commune meeting, a commune cadre said, “Someone’s holding a knife to your neck, and you can still sleep at night?” They wanted us to go back and kill any troublemakers, saying taking the initiative would give us the upper hand. After I came back, I discussed things with the militia commander and others, and we decided to take advantage of the killings that were going on elsewhere by doing away with the class enemies in our village. We ended up killing nine people. In fact, once we started, it was easier than killing chickens. We just tied them up and led them to the river next to the village, and after we killed them we dumped them in the river. We first thought of killing them in the hills behind the village, but someone said that might damage the village’s feng shui, so we changed to the other location. No one resisted; they were all very well behaved. There was just one rich peasant, Zhou Minzheng, who said, “In the old society we ate the rice of exploitation, and we deserve to die. But our kids were born in the New China and grew up under the Red Flag. Can’t they be spared?” But you know how it is, we’d had our meeting and discussed the matter, so how could we spare anyone? We needed to kill them all. All these years my heart has been uneasy, and whenever I think of this incident, I feel an ache in my gut. My conscience won’t let it pass. The fact is that those nine people were all members of our Zhou clan; they were 25th- and 26th-generation descendants of Zhou Dunyi. Now I’m being punished for it, and I have no one to blame but myself. I’m grateful for the leniency of the party and the government.

Looking at this old farmer with his callused hands and etched face standing where a great Confucian philosopher had come into being, we didn’t know what to say. Sometimes words become meaningless, and it’s better to say nothing at all.

At noon on August 17, 1967, the club room of Qingtang Commune was packed with cadres at the level of production team leader and above who had been summoned from all over the district for an impromptu meeting.

At noon the day before, Zhou Renbiao, who was a district tribunal cadre and vice chairman of the district seize-and-push group, had made a special trip to Yingjiang to pass on hearsay about the “enemy situation,” reworked through his personal embellishments, to the district PAFD commander and Red Alliance head, Zheng Youzhi: “Commander Zheng, in the few days since you arrived in Yingjiang, we’ve unearthed two counterrevolutionary organizations. One is the ‘Peasant Party’ led by the old counterrevolutionary Wang Feng at Dashen Mountain, which had grown to 400 or 500 people, and the other is the ‘New People’s Party’ led by the landlord whelp Jiang Weizhu in Jiangjia, which had grown to 700 or 800 people and had its own radio transmitter. These two counterrevolutionary organizations were coordinating with agents of the United States and Chiang Kai-shek to mount an insurrection to attack the mainland.” Zhou Renbiao ended his report by suggesting that Zheng Youzhi come to Qingtang and hold a meeting of CCP members and cadres to stabilize the masses, who were “in a state of confusion.”

That was how Zheng Youzhi, dressed in full military uniform and with a Mauser pistol slung over his rump, jumped on his tractor early in the morning of August 17 and chugged over to Qingtang to preside over the meeting,2 which the competent Zhou Renbiao had managed to put together in just half a day.

Some muddy-footed grassroots cadres had rushed over from nearly 10 kilometers away. Zheng Youzhi had served in the army, so there were two sentries posted at the entrance to the clubhouse, which was festooned with banners proclaiming “Never forget class struggle!,” “Once class struggle is grasped, all problems will be solved!,” and “The enemy is sharpening his knife, and so must we!” The space was too small for the hundreds of people crammed inside it. The farming folk of Daoxian had a habit of carrying long-stemmed pipes with them, and some managed to pull them out for a drag on the pungent local tobacco. Some district and commune cadres had more recently upgraded to self-rolled trumpet-shaped cigarettes or cheap packaged cigarettes. The air of the clubroom was hazy with choking tobacco smoke and the stench of sweat, exacerbated by the heat of the day. Meetings of rural cadres were generally disorderly, with the higher-level cadres holding the main meeting while those below held their own smaller meetings, and the clubhouse rang with the clamor of voices.

The meeting finally began in earnest at 10 o’clock as Zhou Renbiao directed the participants to take out their Little Red Books and stand at attention before a portrait of Chairman Mao. That was an essential procedure in any meeting, large or small, and it brought the clubhouse to a sudden and miraculous silence.

Zhou Renbiao began: “First, let us present our respectful wishes to the reddest, reddest, red sun in our hearts, our most esteemed and beloved great teacher, great leader, great commander in chief, and great helmsman, Chairman Mao!” At this, all the assembled cadres brandished their Little Red Books in rhythm as they chanted in unison, “Long life! Long life! Long, long life!” Zhou Renbiao then led them by saying, “Let us present our respectful wishes to the esteemed and beloved comrade-in-arms of our great leader Chairman Mao, deputy commander in chief Lin!”3 At this, all assembled again brandished their Little Red Books in unison and cried out, “Good health! Good health! Eternal good health!” Zhou Renbiao then invited PAFD commander Zheng Youzhi to deliver the mobilization speech. Over the last few days, Zheng Youzhi’s emotions had been somewhat subdued; taking on the job of frontline commander in chief was a perilous task since the Revolutionary Alliance had snatched PAFD weapons and was growing in strength and aggressiveness by the day, and the PAFD’s failed attack on the No. 2 High School on August 13 still infuriated him. Today, at last, he had a satisfying channel for venting his feelings, and he delivered his speech with great animation, alternately rising to his feet and sitting down again, and punctuated it with thunderous pounding on the table.

A transcript of Zheng Youzhi’s August 17 speech was miraculously preserved. After outlining the general threat posed by the August 8 gun snatching and the armed conflict on August 13, Zheng Youzhi employed considerable artistic license in describing the “complexity of the current struggle between the two classes, the two roads, and the two lines”:

Our District 6 is a focal point for air defense and riot prevention. After the weapon snatching on August 8, a handful of class enemies have taken advantage of a chaotic stage in the Cultural Revolution to carry out sabotage and create disturbances and are prepared to make trouble! We’ve already uncovered two counterrevolutionary organizations. Likewise, in the Zhengjia production brigade of District 8’s Yangjia Commune, the mistress of puppet county head Zheng Yuanzan organized an “Anti-Communist National Salvation Army.” One evening, the production brigade called an admonition meeting for black elements, and after listening for a while, Zheng Yuanzan’s mistress gave a flick of her cattail-leaf fan, and all the black elements rose in unison and began attacking our cadres with their stools. The party secretary quickly called in the militia, who dragged out six or seven black elements and killed them, quelling the riot. During an admonishment meeting in the Xiaba production brigade of District 11’s Shouyan Commune, puppet township head Zhu Mian openly provoked the cadres by saying “You’re messing with us now, but if you’d waited three more days, we would have been organized enough to kill every one of you.” Everyone was furious when they heard that, and they beat him to death on the spot. …

We must comply with Chairman Mao’s instructions: “The people rely on us to organize them; China’s counterrevolutionaries rely on us to organize the people and overthrow them.” The enemy is sharpening his knife, so we must sharpen ours. The enemy is swabbing his rifle, so we must swab ours.

Zheng Youzhi called for each production brigade to keep black elements in line through admonishment meetings and close surveillance, and to kill those who seemed predisposed to staging a revolt. As the meeting was about to end, Zheng Youzhi turned to Zhou Renbiao, who was sitting with him on the podium, and asked, “Comrade Renbiao, is there anything you’d like to add?”

Zhou Renbiao made a name for himself in that instant by saying, “I’d like to add a few words. The public-security, procuratorial, and judicial organs are paralyzed, so once the poor and lower-middle peasants decide to do away with heinously criminal black elements, they don’t need to request instructions in advance or report afterwards; the supreme people’s court is the poor and lower-middle peasants. We have to do away with any traitors among us, even if they’re administrative cadres or those who wear wristwatches and leather shoes.” He then spoke again of the bogus “People’s Party,” saying that one of its members, Tang Yu of Jiujia Commune, wanted to become the district head. He laughed coldly and said, “Today I’ll send him packing to become district head in hell!”

The meeting erupted into chaos, with everyone talking at once. Many were hearing these things for the first time and were thoroughly shocked. Some became agitated, others became apprehensive, and all stared at the men on the podium, whose orders they were accustomed to obeying.

After the meeting adjourned, Zhou Renbiao told Jiujia Commune public-security officer Jiang Bozhu to lead 30 or 40 commune members to Tang Yu’s home in Dayicun.4 Tang Yu was already bedridden with a broken leg from a denunciation meeting on August 14. Now Jiang Bozhu dragged Tang Yu from his bed and out to the rice yard, where the crowd pounced on him and beat him to death and then dumped him in the pond next to his home.

What exactly had Tang Yu done to deserve such treatment? Tang came from a middle peasant family and had once been a primary-school teacher; he was outspoken and something of a busybody. After being labeled a Rightist in 1957, he had been sent back to the countryside to engage in agriculture. When Jiang Bozhu was sent to Tang’s production brigade for work experience as a public-security deputy, he had raised hackles by “jumping a woman.” While others choked with silent fury, Tang Yu had imprudently put his writing skills to work by writing a complaint on behalf of the victim. This resulted in a reprimand for Jiang Bozhu, affecting his career prospects and making him Tang Yu’s sworn enemy. As for Tang Yu’s desire to become district head or such like, we learned that on one occasion, while “giving vent to his hatred of the party,” Tang had said, “If I were allowed to be district head, I could certainly do no worse than they have.” Even if he’d really said such a thing, it was hardly worth a death sentence.

The thing we heard most often during our inquiries was that “Tang Yu was a good man!” But if so, why were so many people willing to beat him to death? “When he was beaten, I didn’t hit him hard,” one participant told us. In fact, Tang Yu would probably have been better off with harder blows. In the killings we looked at, many of the victims were reported to have said, “Please get it over with quickly.”

After the August 17 meeting, five production brigades in Jiujia and Qingtang Communes rapidly exercised the authority of the Supreme People’s Court of the Poor and Lower-Middle Peasants and killed 13 people in four days. In the course of the Daoxian massacre, Jiujia Commune killed 36 people (including four suicides) and Qingtang Commune killed 75 (including nine suicides).

At Qingtang Commune, a poor peasant named Zeng Baobao in the Yueyan brigade had criticized poor-peasant association (PPA) chairman Chen Zhicai and others during the Socialist Education movement, so Chen and the others took their revenge during the “killing wind.” Zeng was more than six months pregnant at the time and was dragged to the killing field with her stomach bulging. She pleaded, “I was wrong, I’ll change. Please don’t kill me! If you must kill me, please wait until my baby is born.” Chen Zhicai said, “We’re not falling for your delay tactics!” He then sliced open Zeng’s belly with a saber, and the fetus spilled out squirming in the blood and gore.

I believe that the “supreme people’s courts of the poor and lower-middle peasants” that became so ubiquitous in Daoxian during the massacre first emerged in Qingtang District, and that Zhou Renbiao and the others were its originators. Before August 17, only 11 people had been killed throughout the county. Most of these killings were concentrated in the area of Simaqiao District’s Yangjia Commune, and investigations found no evidence of a peasant supreme court. After the meeting in Qingtang on August 17, however, peasant supreme courts sprang up like mushrooms at the commune, production brigade, and even production team levels. Our inquiries found that with few exceptions, Daoxian’s peasant supreme courts had no organizational structure and were simply set up to demonstrate the legitimacy, propriety, and revolutionary nature of the killings by declaring “death sentences” in the name of the PPAs. Most of the “chief judges” and “execution supervisors” of the peasant supreme courts were PPA or Cultural Revolution Committee (CRC) chairmen.

The only place where such a court was formally established and hung out a shingle to handle official business was in Qingxi District’s Ganziyuan Commune,5 which decided to establish a peasant court on August 23 after hearing that Yingjiang Commune had done so. The commune’s PPA chairman, Liang Yu, who was a locally funded teacher at the local primary school, was chosen as chief judge, and Liang immediately put his fine penmanship to good use by creating a sign for the court. Worried that the title Supreme People’s Court might be construed as usurping the power of the central authorities, Liang proposed the name “Ganziyuan Commune Higher People’s Court of the Poor and Lower-Middle Peasants,” and a sign to that effect was hung over the commune office door amid the thundering of blunderbusses and firecrackers.

The Ganziyuan court’s first trial considered the case of six members of the Hongwei brigade who had allegedly fled to the hills to mount an insurrection, even though they were actually arrested while laboring in the fields for the double-rush planting and harvesting. Given the manifest absurdity of the charge, balanced by the pressure to do away with “troublemaking black elements,” Liang Yu and other commune leaders decided to show “leniency” by sparing two of the men.

The Ganziyuan peasant court tried a total of 13 people, among whom eight were condemned to death and five were granted “leniency.” That was a relatively civilized outcome at the time, since some kind of “process” was involved and the “criminals” were allowed to defend themselves (whether it actually served any purpose was another question). Notably, among the condemned men were Zhu Yongjin and his two sons, whom Liang himself proposed because Zhu was constantly threatening him over a personal grievance. Eventually, in order to “simplify procedures,” “authority” was delegated to the peasant supreme courts of the production brigades, and the commune’s court became no more than a shell, existing in name only.

Given the checkered history of the peasant supreme courts as an institution, Zhou Renbiao and the others declined the patent on this invention. Some of them defended themselves by saying, “The killings in Daoxian and the supreme people’s courts of the poor and lower-middle peasants were influenced by Guangxi and were a carryover from Guangxi’s Quanzhou County.” Is there any truth to this? We consulted large quantities of documents regarding the Cultural Revolution,6 which show that there was in fact a massacre in Quanzhou County, which adjoins Daoxian, and that Quanzhou did in fact have peasant supreme courts as well as special committees of poor and lower-middle peasants to suppress and eliminate counterrevolutionaries (which Daoxian did not have). However, these organizations emerged after October 1967, so the chronology would suggest that it was Guangxi that came under the influence of Daoxian rather than vice versa. Task Force files related to this issue reveal that organizations such as the peasant supreme courts were the collective creation of a small number of Daoxian’s grassroots cadres. The first to propose such a court was Zhou Renbiao, and the first to carry out a killing in the name of such a court was Tang Zuwang, the CCP secretary of Shouyan Commune’s Pingdiwei brigade.

The Task Force’s investigation established that during the Cultural Revolution killings, Zhou Renbiao on multiple occasions directed, supervised, and encouraged killings in the communes and production brigades under his jurisdiction, that he authorized the killing of 17 specific individuals in several Qingtang Commune production brigades, and that he personally initiated killings at the Jiangjia brigade as an example to the militia. Peasants of Qingtang Township still recall with relish how Zhou brought two bold and brave female “militia officers” along with him to supervise and encourage the killings. He was one of the very few administrative cadres who personally dirtied their hands in the Daoxian Cultural Revolution massacre.7

Qingtang District’s Wutian Commune deserves its own section because of its former CCP secretary, Xiong Liheng, who later became deputy CCP secretary of Daoxian.

During the 1967 massacre, Xiong Liheng was still CCP secretary of Wutian Commune. As a member of the ruling faction, he underwent some trivial attacks at the outset of the Cultural Revolution, but this didn’t stop him from playing a role in Wutian’s political arena as a “revolutionary leading cadre.” When we went to Wutian to interview people about the massacre, one grassroots cadre offered the following assessment of “our Secretary Xiong”: “He’s quite remarkable—able, competent, and audacious.” So how did Xiong Liheng use his abilities, competence, and audacity during the Cultural Revolution killings? During our reporting, we found that Xiong utilized his subsequent power and prestige to obscure his role in the killings.

During the killing wind, 42 people were killed at Wutian Commune (including three suicides). Four meetings were held during this time, the first three to mobilize and engineer the killings and the fourth to end the killings. Xiong figures in both types of activities. Most of the killings occurred in two rounds: the first around August 23, when 12 people were killed under the influence of Qingtang District’s three-level cadre conference, and the second around August 26, when 28 people were killed through the arrangements of the commune’s August 24 “seize-and-push” meeting. The worst of the killers was the commune’s PAFD commander, He Mengxiang, and the greatest number of killings occurred in the Wutian brigade, where 11 died under He Mengxiang’s personal instigation. The second-highest number of killings occurred in the Jiangjiadong brigade, with eight dead, and we detected Xiong Liheng’s hand in these killings.

After cadres from the Jiangjiadong brigade took part in the August 24 commune seize-and-push meeting, they immediately held a meeting to inform other cadres of the commune leadership’s instructions and to draw up a list of people to kill. A meeting later in the evening for cadres and PPA representatives added two more names to the list, for a total of 12.

At nightfall on August 26, the production brigade militia brought in all the killing targets and locked them up in the brigade’s storehouse, except for one class enemy offspring who resisted and was killed on the spot. Brigade militia commander Zhu Baosheng then telephoned the commune to request instructions from Secretary Xiong, telling him that the brigade had already drawn up a name list and reporting on their class status, performance, and other details. Xiong recited two of Chairman Mao’s quotes: “The core power that guides our undertaking is the Chinese Communist Party, and the theoretical foundation that guides our thought is Marxism-Leninism,” and “Policy and strategy are the life of the party; leading comrades at all levels must pay close attention to this and must never be negligent.” He then instructed Zhu: “I’ll leave it up to you whom to kill. I have no opinion on the rest, but you have to take note of policy and strategy, and you need to distinguish between black elements and offspring.”

After Zhu Baosheng hung up the phone, he and production brigade head Zhu Yongsheng quickly held a meeting with 11 militia cadres and passed on the instructions from Secretary Xiong. After discussion it was decided to show leniency to five people (all offspring) and to kill only six, five of whom were black elements and the other of whom was a troublemaking landlord offspring whose killing could serve as a warning to others. The five handled leniently were released after being “educated” that night. (On this point, Xiong Liheng told the Task Force that he not only didn’t order any killings but actually saved five people.)

The next day (August 27), a mass rally was held for the entire production brigade to “promote democracy” by having everyone raise their hands in a vote. The six condemned people were led bound onto the stage. Presiding over the meeting, Zhu Baosheng announced the crimes of the six, then read out a name and asked, “Whoever agrees to kill this person, raise your hand.” The masses cried out their agreement in unison, and all raised their hands.

After completing this process, the militia took the six out to the hills behind the village and shot them with fowling pieces. Counting the man killed during the roundup, this brought the death toll to seven. One other landlord offspring was later killed after fleeing and being captured elsewhere. By the time he was brought back, the commune had already transmitted the 47th Army’s prohibition of further killings, and everyone said to just let him be. But Zhu Baoshen and others disagreed, saying, “If he hadn’t fled, we wouldn’t need to kill him. But once he’s fled and been brought back, how can we not kill him? During Land Reform it was the same: landlords and rich peasants who ran off all had to be killed after they were caught and brought back.” They then led several militiamen to secretly kill this eighth man in the middle of the night.

Wutian Commune’s Xincha brigade didn’t kill anyone during the first or second wave of killings. It wasn’t as if this production brigade had no black elements, or that the brigade’s black elements were particularly well behaved; in the words of one of the brigade’s cadres: “Behavior is what you say it is, good or bad.” So why were there no killings in this brigade? It turns out that members of the brigade who might have been targeted had rather complicated backgrounds: someone in the family was a cadre somewhere, or the clan was especially powerful. In any case, their deaths would be noticed, unlike the class enemies in other brigades who could be killed without anyone raising a fuss. The cadres and masses of the Xincha brigade didn’t want to get tangled up in this kind of controversy. Even when they came under pressure from cadres sent from the regional and commune headquarters to monitor the situation, the leading cadres of the Xincha brigade just gritted their teeth, and the word “kill” never passed their lips.

On September 8, Wutian Commune convened a cadre meeting to discuss the issue of “seizing revolution and pushing production.” At the meeting, Xiong Liheng specifically criticized the Xincha brigade for its conservative thinking, fuzzy understanding, and softheartedness on the cardinal issue of struggle with the enemy: “That fellow Zhu Mei in the Xincha brigade is incorrigible, always causing trouble and committing sabotage. He was a trainee pilot under the Kuomintang and comes from a powerful family. Letting him live won’t help build our country and is dangerous to the leadership of your brigade. If you don’t kill him now, it will only be harder for you later. If your brigade is afraid to do it, we can send people from the Tangxia and Xiawen brigades to assist you.” Cadres from the other brigades began jeering, humiliating the cadres of the Xincha brigade. Smirking, Xiong Liheng asked the Xincha cadres, “Do you agree to the killing?” The cadres replied in unison, “We agree!” “Do you want the Tangxia and Xiawen brigades to help you make revolution?” “No, we’ll make revolution ourselves!”

That day after lunch, Xincha militia commander Tang Guilong summoned Zhu Mei, repeated what Xiong Liheng had said word for word, and then represented the brigade’s peasant supreme court in pronouncing the death penalty. Several militiamen came forward and killed Zhu Mei with their fowling pieces, thus carrying out Secretary Xiong’s directive less than four hours after the commune meeting adjourned. Zhu Mei was the Xincha brigade’s only victim during the Daoxian massacre.

In practical terms, Xiong Liheng’s behavior was nowhere near the worst in the Daoxian massacre; the commune he led killed only 42 people, fewer than many production brigades, not to mention other communes. Few offspring of black elements were killed, and there were few instances of household annihilation, gang rape, or killing for financial reasons. In a sense, Xiong was actually a moderate, and killings at Wutian Commune commenced only after a district meeting from August 20 to 22, during which Jiujia Commune was praised for its swift action while Wutian was criticized as conservative. I have no intention of defending Xiong Liheng, but given that so many other cadres were so much worse, he can be considered among the more circumspect, and since I’ve related his story, it’s my responsibility to make this clear. At the same time, seeing how an able, competent, and policy-minded commune leader such as Xiong Liheng became caught up in the killing wind also deepens our understanding of the nature of this massacre.