![]()

BACKSTORY

Pre-1914 History

The Kaiserliche Marine developed enormously in the forty-three years from its very humble beginnings at the foundation of the German Empire in 1871 as the amalgamated Prussian and North German Federation navies to the beginning of World War I. In the centuries before 1871 the German Empire never created a navy, letting the coastal cities and kingdoms guard their own maritime interests. After the empire’s collapse in the Napoleonic wars and its acquisition of the Baltic territory of Pomerania from Sweden, Prussia established a small navy. In 1848 the German revolutionary National Assembly formed a fledgling navy to serve in the war against Denmark. The outnumbered fleet fought a small battle at Helgoland but could not break the Danish blockade. In the Prusso-Danish War of 1864 the Prussian fleet, together with an Austro-Hungarian squadron, met the Danish blockade fleet off Helgoland but once again failed to drive the Danes from their station.

In the following years the Prussian fleet, under the command of Prince Adalbert, trained officers and crews while new ships slowly entered service. A North Sea base was established in Wilhelmshaven and another in the Baltic at Kiel. In 1867 the North German Federation was founded under Prussian supremacy, and a new national ensign, which flew until 1918, was hoisted on the ships. Anticipating conflict with Denmark, the navy ordered small gunboats of questionable value. But soon France was seen as a potential enemy, so three armored frigates were ordered in France and Britain, as well as four more in Germany, to support the construction of iron ships—an industry just beginning in Germany. When war with France broke out in 1870 only three armored frigates were in service, and once again the German navy found itself unable to prevent a superior enemy fleet from blockading its coasts.

In 1871, at the end of the war, the German Empire was formed when the four South German states joined the North German Federation. Whereas the armies remained separate, acting together only in war, the navy came under the emperor’s direct control. Its growth accelerated when Emperor Wilhelm II was crowned in 1888. Two months later the parliament readily granted his request to fund a division of four modern Brandenburg-class battleships. Soon the emperor noticed a young captain, Alfred Tirpitz, who had distinguished himself in the development of torpedoes and torpedo boats. Although at this time the Jeune École school of naval theory envisioned torpedo boats as coastal craft, Tirpitz called for high-seas torpedo boats to operate together with the battleships. In 1892, at the age of just forty-two, he was appointed chief of staff of the Naval High Command and in 1897 State Secretary of the Reichs Marine Amt (Naval Administration), becoming the de facto naval minister.

Wilhelm II favored a fleet of cruisers, but he could not impose this idea on Tirpitz, who redirected Germany’s naval policy to an offensive orientation. In fact, Tirpitz considered a fleet of seventeen battleships and six torpedo boat flotillas necessary in order to cope with the French and Russian navies simultaneously. The parliament balked at these plans and only reluctantly approved funds for two additional battleships of the Kaiser class to join the three already authorized. In 1898, however, parliament accepted a bill asking for nineteen battleships in two squadrons plus two reserve ships; twelve of this total number, including old, coastal, armored ships, were already in service. Three battleships were laid down in 1899 and three more in 1900. Tirpitz felt this rate of construction was desirable, but as it could not be sustained under the existing naval law, which dictated construction through 1903, Tirpitz convinced the emperor to build at a rate that would lead to forty-five battleships by 1920. Tirpitz’s aim was a battle fleet strong enough to deter Britain from entering war with Germany. He assumed a decisive battle in the southern part of the North Sea and from 1907 on had the ships constructed to the prerequisites of such a battle: smaller-caliber guns, slower speed, but superior protection.

In the second naval bill of 1900 Tirpitz asked for four squadrons of battleships of eight units each, with two flagships and four reserve vessels—that is, thirty-eight battleships. The old, coastal, armored ships were to be quickly replaced. The “Dreadnought leap” resulted in additional supplementary bills in 1906, 1908, and 1912, which were pushed through parliament and would have eventually led to a German fleet of sixty-one battleships. However, against Tirpitz’ expectations, Great Britain reacted violently, and by 1910 it became clear even to Tirpitz that a naval arms race with Britain could not be won. Fiasco was imminent. It was too late, however, to stop what had become a runaway train.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, many in the Imperial German Navy considered submarines useless for a powerful navy that could sustain the Germany’s world position. In fact, at this time no existing submarine anywhere offered features that inspired confidence in the type’s capabilities in a future conflict. Insufficient sea-keeping qualities, speed, and endurance prevented submarines from deepwater operations with battle fleets. Instead, they were seen as defensive weapons for protecting harbors or sealing limited areas against enemy raids; they were often regarded in the same category as mines and barriers.

Thus, Germany was the last major naval power to employ submarines. The private German shipbuilding companies Howaldtswerke AG and the Krupp-owned Germaniawerft AG had constructed military submersibles since 1898. Only in 1904 was Germaniawerft AG awarded a contract to build the German navy’s first submarine. The boat was based on a design for the Russian navy, and changes repeatedly delayed its completion. In accordance with common German practice for small naval units, the vessel received no name but a designator—the letter U, for Unterseeboot, or U-Boot, and a number, starting with 1. On 14 December 1906, U 1 was commissioned at Kiel. Several improved designs followed with increased displacement and endurance and enhanced technical reliability, but the early boats still suffered from insufficient battery capacity, and their low-power, petroleum-driven main engines produced telltale smoke clouds during surface travel. In 1913, following the development of powerful and reliable diesel engines, the first series of diesel-powered U-boats (U 19–U 22) entered service. Prewar maneuvers had shown them capable of patrols lasting a week under all weather conditions.

Mission/Function

In an 1892 study the Naval High Command planned to prevent an enemy blockade of the German coast, as experienced so often in the past, and to act offensively in the event of war with France and Russia. The French Atlantic Squadron was to be destroyed first, before it could unite with the Mediterranean Squadron, even at the risk of the devastation of Danzig by the Russian fleet. Hostilities with Britain were not officially taken into account until later. When they were, the planners assumed the British would implement a close blockade and envisioned meeting the British fleet between Thames Estuary and Helgoland in a decisive battle.

When Tirpitz became secretary of state of the empire’s navy department (Reichsmarineamt, or RMA) in 1897, the imperial navy possessed a disparate assortment of vessels. The most powerful units were the four battleships of the Sachsen class (7,368 tons) and the four Brandenburg-class units (10,000 tons). Some coastal armorclads of the Siegfried class (3,500 tons), built in accordance with the expired defensive doctrine, were also in service.

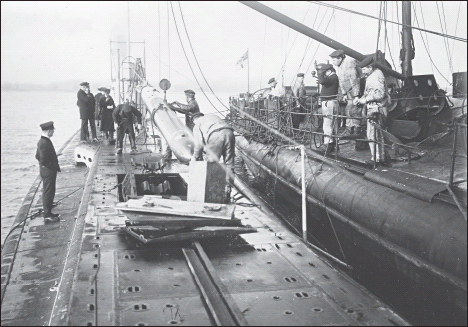

Photo 3.1. U 27 loading torpedoes. (Peter Schenk collection)

Under construction or authorized were three battleships of the Kaiser Friedrich III class (11,100 tons). For these vessels the design criterion of the strongest main artillery possible—a feature of the Brandenburg class—was abandoned. Instead, on the basis of contemporary experience, these ships were armed with quick-firing guns, in order to deluge the enemy with shells. The so-called heavy artillery at this time consisted of four 24-cm guns (Schnellfeuergeschütz-Sk)—the largest caliber capable of sustaining a high rate of fire. In fact, the eighteen 15-cm Sk guns were the real main weapons of this ship class. The belt armor consisted of 300 mm of the newly developed Krupp Cemented (KC) armor. Speed reached nearly eighteen knots. In the first fleet law, two more of these ships were authorized. The next, five-unit Wittelsbach class (11,700 tons) was a follow-on design. Its armament was identical; the main modification was rearranged armor plating. A 75-mm armored-deck slope was positioned behind 225-mm belt armor, and speed was increased slightly.

Emperor Wilhelm II had great interest in the navy, and he was especially fond of cruisers. Thus he strongly influenced the conception of the Hertha-class cruisers (5,660 tons). The armament consisted of two 21-cm and eight 15-cm Sk guns. The speed (19.5 knots) and protection (armored deck only) of these vessels were insufficient, however, and this type was not continued after Tirpitz entered office. Contemporaneous to the Kaiser Friedrich III class was the first German armored cruiser, Fürst Bismarck (10,690 tons). She was a cruiser version of the aforementioned battleships armed with four 24-cm and a dozen 15-cm Sk guns. Her speed was only nineteen knots, but the belt armor was up to 200 mm thick amidships.

The armored-cruiser equivalent to the Wittelsbach class was Prinz Heinrich (8,890 tons). She was a little smaller than her predecessor but, at twenty knots, slightly faster. Armament had been reduced to a pair of 24-cm and ten 15-cm Sk weapons. Protection consisted of a 100-mm thick layer of belt armor and a 50-mm armored-deck slope. The material was KC steel for the belt armor and nickel steel for the armored decks.

From 1897 the need for a type suited to fleet and colonial use resulted in the light cruisers of the Gazelle class (2,660 tons). Capable of up to twenty-two knots, these cruisers were armed with ten 10.5-cm Sk guns. There was only local shielding and an armored deck for protection. Many of the older cruisers served in colonial stations and were then assigned auxiliary tasks.

Torpedo boats played a role in Germans doctrine second only to battleships. Tirpitz himself strongly affected the progress of this type from 1878, as a leader of the technical development of torpedoes, and then from 1886 to 1889 as chief inspector of the torpedo department. Very different boats were investigated, with the goal of vessels as small and fast as possible. Since the speed, range, and directional control of the early torpedoes were inadequate, the boats had to close very near to their targets and so required conditions of low visibility to operate successfully. In this first phase, boats of the Elbinger shipyard, in Schichau, proved very useful. A larger unit was also designed as a division leader.

When Tirpitz became secretary of state, a typical torpedo boat was S 82, with a displacement of 142 tons and a speed of twenty-five knots. She was armed with three 45-cm torpedo tubes and a 5-cm Sk gun on a torpedo-boat gun carriage (a combination known as Tk). A corresponding leader was the division torpedo boat D 9, with a displacement of 350 tons, a speed of 23.5 knots, three 45-cm torpedo tubes, and three 5-cm Tk guns.

As weapons improved, consideration regarding the ideal size for torpedo boats was ongoing. Positive experience with the division torpedo boats encouraged an enlargement of the type, which would also improve their seaworthiness. The result was the high-seas torpedo boat with a displacement between 310 and 580 tons and a speed of twenty-seven knots. Armament consisted of three deck-mounted 45-cm tubes and three 5-cm Tk guns. The division torpedo-boat type was suspended.

According to Tirpitz’ strategic conviction, the decisive instrument of sea power was the battle fleet. The so-called standard ships of the line formed the basis for Tirpitz’ planned fleet expansion. As a first step he consciously accepted that the size and characteristics of these ships were below international norms. The battleships of the planning years 1900–1903 were the five Braunschweigs (13,200 tons) and five Deutschlands (13,200 tons). Their armament was moderately enhanced to four 28-cm and fourteen 17-cm Sk guns. The armor strengths remained the same for the first ships and changed only insignificantly in the last ones. The maximum speed reached eighteen knots.

The contemporaneous two-unit, armored-cruiser classes of the Prinz Adalbert (9,050 tons) and Roon (9,530 tons) types carried four 21-cm and ten 15-cm quick-firing guns. Their armor resembled that of their predecessors, but the Roons were one knot faster. Significant improvements were not achieved until the two ships of the 1903/04 Scharnhorst class (11,600 tons). That class’s armament consisted of eight 21-cm and six 15-cm quick-firing guns. The deck armor improved somewhat, and the belt armor thickened to 150-mm. The maximum speed was 23.5 knots. Apart from colonial duties, German armored cruisers could undertake reconnaissance in force and support the battle fleet.

Systematic firing tests conducted in 1904 at Meppen demonstrated that the 100-mm belt armor of the armored cruisers was insufficient, while comprehensively investigating the interaction with the deck slope behind the belt armor. Such firing experiments on actual-sized ship modules played an important role in the design of new units. As soon as the end of 1904, several influences were generating discussion about increasing battleship sizes. These influences included an increased accuracy and rate of fire of heavy gunnery, the growing threat presented by torpedoes and mines, and initial lessons from the Russo-Japanese War.

At first such considerations were retarded by German reluctance to appear as a driver in the expansion of ship sizes. Furthermore, an increase in battleship size would require costly expansion of locks and widening of the Kiel Canal. Rumors of larger British battleships and then the construction of the Dreadnought provoked this policy’s reversal. The result was the first German all-big-gun battleships, the Nassau class (18,900 ton). They were armed with twelve 28-cm and twelve 15-cm naval guns. The hexagonal arrangement of the six 28-cm twin turrets was thought to offer advantages during a melee. The maximum speed was twenty knots. The ships had a new and effective underwater protection system and a maximum belt armor of 300 mm.

An unusual feature of the design organization was that parallel to the titular head of the construction office was a young official, Hans Bürkner, designated by Tirpitz to be responsible for capital-ship construction. Many of his design measures led to the remarkable survivability of German capital ships. He conceived of a large float (called Ponton I) for underwater explosion tests. This allowed for actual-sized ship sections to be stressed with explosion charges and torpedo-bulkhead prototypes to be tested under near-real conditions. The cruiser design corresponding to the Nassau class was Blücher (15,840 tons), the Germans’ ultimate expression of the classical armored cruiser: twelve 21-cm guns in the same main-battery arrangement as Nassau, a secondary battery of eight 15-cm guns, protection featuring torpedo bulkheads, and twenty-five knots. Despite the considerable progress from her forerunners, Blücher remained an armored cruiser, not a battle cruiser (both types were labeled “large cruisers” in the imperial navy).

The German answer to Invincible was the battle cruiser Von der Tann (19,400 tons), with eight 28-cm and ten 15-cm guns. Speed was twenty-seven knots. With torpedo bulkheads and strong armor (belt armor maximum 250 mm) she was very well protected. Along with these radical changes in capital-ship design, systematic development was occurring in light cruisers and torpedo boats.

ORGANIZATION

Command Structure

Administration

From 1899 on, the kaiser was the Kaiserliche Marine’s supreme commander. The offices reporting to the kaiser included the commanders of the Naval Cabinet, of the Naval Staff, of the High Seas Fleet Command, of the Cruiser Squadron, of the North and Baltic Sea naval stations, of ships on foreign station, and finally, the State Secretary of the Naval Administration, Grand Admiral von Tirpitz. Tirpitz headed the naval administration, which had personnel, technical, and educational departments. Thus, the navy did not have a centralized professional leadership. This led to contradictory strategic proposals. All orders had to be given by the kaiser, in contrast to the army. Von Tirpitz’ request for general command over the navy was rejected. He was finally removed from his post in March 1916. Only in September 1918 did Admiral Reinhard Scheer, newly appointed head of the Admiralty Staff, succeed in establishing an operational branch (Seekriegsleitung) at the Grand Headquarters at Spa, thus taking de facto the high command from the emperor.

The budget of the navy for the 1912/13 fiscal year amounted 462 million marks, compared to 899 million marks for the British navy in the same period. The next year’s budget was 476 million marks, compared to 1,051 million marks for the Royal Navy.

As for command and fleet organization, territorial commands administered the North Sea coast (Marinestation Nordsee) and the Baltic coast (Marinestation Ostsee). There were also six overseas stations. The cruiser squadron was stationed at Qingdao, Germany’s only foreign base with docking facilities. In the Mediterranean the battle cruiser Goeben and the light cruiser Breslau, and in the Caribbean the light cruiser Karlsruhe, were deployed without a German base. The cruiser Königsberg was stationed in East Africa and smaller units in West Africa and the South Pacific. The navy’s inspector-general was Grand Admiral Prince Heinrich von Preussen.

Fleet Organization and Order of Battle

At the beginning of the war the High Seas Fleet was in Wilhelmshaven, under the command of Admiral Friedrich von Ingenohl, on board his flagship Friedrich der Große. There were three squadrons; the first, under the command of Vice Admiral Wilhelm von Lans, comprised the eight battleships of the Nassau and Ostfriesland classes. The second squadron, (II Squadron) under Scheer, who had become a vice admiral in 1916, was made up of the five predreadnoughts of the Deutschland class and the predreadnoughts Hessen and Lothringen. The third squadron, under Rear Admiral Felix Funke, comprised the four battleships of the Kaiser class. Later, in 1914, the four new battleships of König class and in July 1916 Bayern were included in this squadron. In 1917 Baden became the flagship, and then a fourth squadron was formed with the five battleships of Kaiser class, splitting the third squadron. The second squadron left the High Seas Fleet after Jutland. A fourth and fifth squadron that existed in 1914 consisted of old predreadnoughts, soon relegated to secondary service.

The first reconnaissance group, under Rear Admiral Franz Ritter von Hipper, comprised the battle cruisers Seydlitz, Moltke, and Von der Tann and six small cruisers. Later, in 1914, Blücher and Derfflinger were added, with Lützow coming in during 1916 and Hindenburg in 1917. The second, third, and fourth reconnaissance groups had five light cruisers each. There were eight torpedo-boat flotillas with eleven or twelve boats each, with additions made during the war. (See table 3.1.)

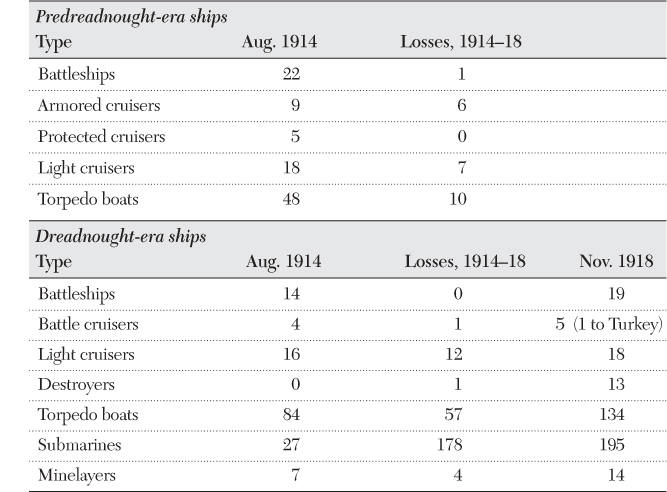

Table 3.1 Strength of Kaiserliche Marine

Communications

Tactical communications were conducted with flag signals during the day and by signal lights at night. To ensure receipt, by the time of the battle of Jutland, signals were repeated by wireless.

Wireless telegraphy had become an indigenous and reliable communication system by 1900, and in 1912 a monopoly quarrel between the British Marconi and the German Telefunken systems had been settled. In 1905 the navy built a wireless station with a range of two thousand nautical miles at Norddeich, in cooperation with the post ministry. In 1908 Telefunken introduced an innovative long-wave transmitter that could be carried by all Kaiserliche Marine ships. From 1911 a long-range transmitter at Nauen, near Berlin, with a range of five thousand nautical miles, was able to reach German colonies. Airships and bigger planes were equipped with small wireless sets. In the summer of 1914, however, the building of a worldwide wireless net had not been finished. There were big stations at Kamina in Togo, at Windhuk (in modern Namibia), at Qingdao, and on Yap in the Carolina Islands, and a number of smaller ones. But the stations in Tabora in Deutsch-Ostafrika and on Sumatra were not yet finished, so parts of the Indian and Pacific Oceans remained out of range.

Intelligence

The Nachrichtenbureau (N) in the Imperial Naval Administration collected intelligence from other navies. At the beginning of the war no naval deciphering service existed. In March 1915 a radio station of the Royal Bavarian army’s Funkerkommando 6 at Roubaix observing enemy wireless traffic succeeded in breaking the British patrol-boat code and in July 1915 the British fleet code. From 1917 the British and French naval signal books were broken. Also, from spring 1915 the positions of allied merchant vessels could be determined by taking the bearings of wireless transmissions. Later in the war the Royal Navy introduced more sophisticated codes that were harder to decipher. These code-breaking successes were accidentally achieved by the ex–University of Würzburg mathematics professor Ludwig Föppl, then twenty-six years old, who had been sent to the wireless station by chance. In February 1916 the navy created the Beobachtugs- und Entzifferungsdienst (B.u.E. Dienst) at Neumünster, under Lieutenant Commander Martin Braune, for observation and deciphering of enemy radio messages. Braune had been sent to Föppl to learn from him. The information gathered from this activity was often stunning; it ranged from the deployments of Q-ships to minefields and losses in them, as well as to exact numbers of merchant ships around Britain.

The practice of wireless communications was still very young in 1914, and the German Naval Staff was unaware of the security problems connected with it. Some simple precautions were thought to be sufficient. A secret signals book was used, and tables were changed from time to time. Germany used three code books, one (Handelsverkehrsbuch) for the merchant vessels and smaller warships, one (Verkehrsbuch) for the diplomatic service and interservice communication, and the navy’s signals book (Signalbuch der Kaiserlichen Marine), issued only to larger units on important missions.

All radio messages from ships were to be sent with the lowest possible signal strength, in the belief that enemy land stations would not then be able to intercept them. The normal procedure was for the main radio station, usually on the flagship, to ask every single recipient of a message for an acknowledgment. The practice generated excessive traffic, with many repetitions, from which enemy observers could conclude a great deal.

When the German light cruiser Magdeburg ran aground in the Baltic in August 1914, the Russians captured the ship’s signals book, a copy of which they handed over to the British. A new set of codes was ordered instantly, but it took two month to distribute. From 1915 codes were replaced at first monthly, later daily. But the request of the commander of the Baltic Forces for a new signals book was rejected by the Admiral Staff in May 1915. Only in December 1915 was the signals book improved. Two new signals books, for fleet and general signals, were finally introduced in 1917. As a result of all this, on the eve of the battle of Jutland the British were fully informed about German intentions from German radio signals, and the Grand Fleet went to sea in time to intercept the German High Seas Fleet.

Positive results and a more cautious attitude toward radio signals could be observed in October 1917 during a mission of the cruisers Bremse and Brummer against a convoy east of Lerwick. The cruisers kept wireless silence and remained undetected. Brummer had a radio observation squad on board that could jam the alarm message of the British destroyers escorting the merchant vessels. The cruisers sank eight merchant vessels and one destroyer. British messages giving the positions of intercepting forces were deciphered and courses were adjusted so that the cruisers’ return was unmolested. Another dash of the High Seas Fleet against the Bergen-Shetland convoys in April 1918 was also undetected because of German radio silence until a machinery malfunction on Moltke forced her to broadcast. By that time it was too late for the Grand Fleet to intercept.

Infrastructure, Logistics, and Commerce

Germany entered the war unprepared, in the firm belief that it would be over by autumn. It soon became clear that this would not be the case. The complete blockade of overseas supplies was quickly felt. Industrial managers pointed out that the supplies of saltpeter imported from Chile for production of explosives would last only half a year. As a result, a department for war raw materials (Kriegsrohstoffabteilung) was established, with military and civilian deputies, and the chemical industry was brought together in a syndicate to mass-produce artificial saltpeter from nitrogen gas.

Also, food production began to suffer from a shortage of labor as farmers and their sons were conscripted and workhorses requisitioned. Germany had to import 10 percent of its food before the war. At the end of 1914 a central grain organization was set up, followed in 1916 by a war food administration, which, however, proved inefficient. By the end of 1916 a crisis existed in terms of transportation and coal, caused by the lack of railroad workers. The winter of 1917 became notorious for people having only turnips left to eat. The need for labor in industry was partly alleviated by the employment of five million women.

As most German warships used coal, a fuel that Germany had in abundance, there was no scarcity in this sphere. The need for oil was much smaller than it would be in the Second World War, but nevertheless it was critical, as of the 1.3 million tons consumed in 1913 only 90,000 tons were produced domestically. At first oil could still be imported from Galicia, then a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. But the region was soon occupied by the Russians, until regained in spring 1915 (luckily the Russian army did not bother to destroy the oil wells when it retreated). Romania also stopped its oil exports, under allied pressure, and a crisis in supplies occurred in 1916. Romania entered the war that year and was occupied in spring 1917 by German and Austro-Hungarian forces. The British destroyed the oil wells before the allied retreat, but German workers quickly repaired them, and by the end of the year production had been restored to half its previous level. Overall, Germany could provide about 80 percent of its prewar annual oil consumption, which compared unfavorably with allied countries, which doubled their supplies during the war.

Manganese ore, an important raw material for steel production, was imported from Turkey. Only after Serbia was overwhelmed in October 1915 could it be shipped by rail from Constantinople to the Danube and from there to Germany. When the railway in Serbia was reopened at the end of 1915 the traffic became faster, and from three to five thousand tons per month could be sent to Germany.

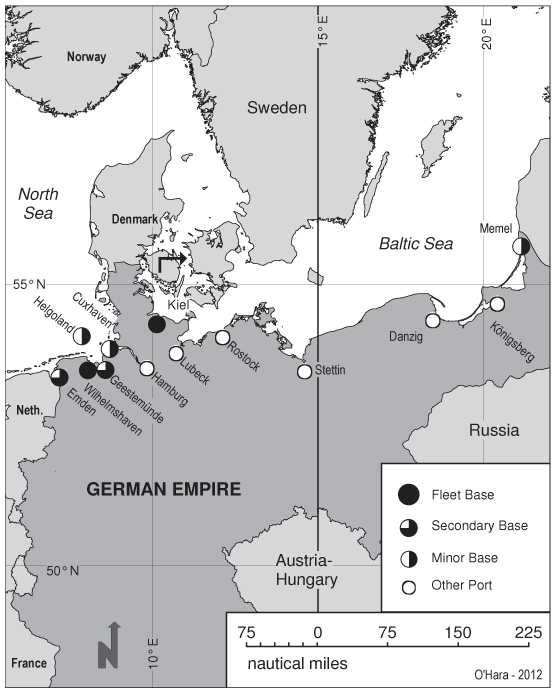

Bases

The two chief military ports with docking and supply facilities were Wilhelmshaven and Kiel. On the North Sea coast there were also harbor commanders for Geestemünde (today Bremerhaven), Cuxhaven, and Helgoland. In 1895 the Kiel Canal was opened, connecting the North and Baltic Seas without the detour around Jutland. The locks were widened for the new battleships in 1914, just before the war. The only German overseas base for the cruiser squadron was at Qingdao, which possessed a floating dry dock. Because of the need to supply the overseas cruisers in the event of war, the German navy prepared a number of stations, called Etappen, in Qingdao and in neutral countries, commanded by naval officers who cooperated with businessmen in chartering German and neutral coal ships to rendezvous with raiders. These stations were officially part of the embassies and were connected by wireless with ships and naval commands. There were such stations in China, Japan, Manila, Batavia, San Francisco, Peru, Valparaiso, La Plata, Rio de Janeiro, the West Indies, New York, West Africa, East Africa, and the Mediterranean. With the destruction of most raiders by the end of 1914 and the declaration of war against Germany by many countries, the stations lost their importance. During the war, more bases were set up in occupied countries—for example, Zeebrugge and Ostend in Flanders, and Memel, Libau, and Riga in the Baltic. At Zeebrugge, submarine pens were built. In the Black Sea, small bases were built at Varna and Costanza. (See map 3.1.)

Industry

The navy had its own shipyards at Wilhelmshaven and Kiel. There were larger, civilian yards at Emden, Geestemunde, Hamburg, Lübeck, Rostock, Stettin, Danzig, and Elbing. In 1900 there were a total of thirty-nine yards, with 154 slipways and twenty-seven docks. Krupp at Essen produced armor and guns, and armor was also made at Dillingen. Before the war Germany ranked second only to the United States in coal and steel production. The country had very good rail and canal networks.

Shipping

In 1914 Germany had two thousand merchant ships totaling 5,134,720 GRT, amounting to 11.3 percent of the world’s total. When war started German merchant shipping almost ceased, with the exception of the iron-ore traffic from Lulea in Sweden via the Baltic, which had to stop in winter due to ice. Some 7 percent of Germany’s iron-ore shipments could be maintained from Narvik by the safe route through Norwegian territorial waters. A large amount was also shipped from Narvik to neutral Holland until British diplomatic pressure stopped this traffic. Lower-quality “minette” iron ore was also available from Lorraine.

Only a handful of ships tried to run the British blockade. One was the Rio Negro, which returned from the Caribbean with the survivors from the sunken cruiser Karlsruhe. Neither the Russian navy nor the few British submarines that entered the Baltic Sea caused much harm to Germany’s Baltic traffic. British and Russian submarines sank fourteen merchant vessels totaling 28,000 GRT in 1915, Russian submarines sank another three ships in 1916; there were no losses to submarines in 1917–18. Apart from diplomatic pressure on Denmark and Sweden to close the Baltic’s western entrances to enemy warships, the German navy laid minefields, ordered patrols, and at the end of 1915 installed a net barrage from Wustrow to Gedser. More nets followed in spring 1916 in Langeland and Fehmarn Belt, as well as in Baagösund and Öresund.

Demographics

In 1914 the Kaiserliche Marine had 3,878 officers and 65,091 ratings, plus 3,582 clerks. A further 13,200 ratings could be activated from reserve status at the beginning of the war, but as this exceeded the need at that time they were mostly used in the Marinekorps Flandern, on the western front.

Training

The navy conscripted for military service all men over seventeen years of age who had at least three months’ experience on ships or river craft. Volunteers from the technical professions were also inducted for a period of three years and then placed into the reserve for a further four years. Boys could enter the navy from age sixteen and after graduation to sailors could become noncommissioned officers.

Every April the navy accepted two hundred officer candidates (in 1914 the number was raised to three hundred). They were given one month of infantry training, then were sent on board a sail training vessel that spent several weeks cruising the Baltic before departing overseas, to return the following spring. The cadets had to pass an examination to become midshipmen. They were then educated for another year at the naval academy, which from 1910 was situated in an impressive brick building in Flensburg-Mürwik. After another examination they received an additional two years’ training on board ship.

Engineer officer candidates had to first apprentice for thirty months in facilities building ship’s machinery. Then, after infantry drill, they spent half a year on board ship and another six months in education on land. An examination followed, after which the candidates had another two years of shipboard training.

Culture

In the nineteenth century, before forced to change the system, the Prussian army had only officers of noble birth. The navy, as a younger branch of the armed forces, did not have this limitation, and in 1914 only 9 percent of naval officers were nobles. There was much discussion over whether candidates passing their college final examinations should have a shortened training period, as was the case in the army. Those in favor considered a broader education to be advantageous, while opponents—who won the argument—feared a lower esprit de corps and a less malleable group of young men. The lower status of the engineer officers was another source of friction, which was not solved until after the war.

Generally the naval officer corps was very loyal to the kaiser, to whom they owed much. There was little or no tolerance for free discussion, and differing opinions tended to be suppressed.

THE WAYS OF WAR

Surface Warfare

Doctrine

The strategic aim of the Kaiserliche Marine was to win a major battle against the British Grand Fleet in the southern North Sea, under conditions favorable to the German side. It was assumed that the Royal Navy would mount a close blockade of the German ports and that it could be worn down by mine warfare, torpedo boats, and submarines prior to this decisive battle. After substantial losses had been inflicted on the Grand Fleet, it was hoped, German overseas traffic could resume. Opponents of this approach, such as Vice Admiral Karl Galster, favored a “cruiser war” concept but had no answer to the problem of the disruption of German overseas traffic and thus were silenced by Tirpitz. Shipbuilding policy, gun development, and tactical training all advanced the strategic aim of a decisive fleet engagement.

The greater gun caliber and range of the British dreadnoughts was acknowledged, but in the primarily misty conditions prevalent in the North Sea the performance of German guns at shorter range was initially deemed superior. (The battle of Dogger Bank occurred on one of the rare days of good visibility.) A battle was to be fought in line ahead, with torpedo boats making attacks from the lee side. Tirpitz considered a close-in melee between the battle fleets as a means to tackle the superior enemy fleet. Therefore, the German battleships had medium guns for close-range action and, in the early classes, a hexagonal turret layout to allow engaging on both sides. Tirpitz also hoped that with their good protection even heavily damaged ships would be able to make it back to their nearby home ports.

Ships

Battleships

Of the predreadnoughts, the ten ships of the Braunschweig and Deutschland classes were still in service with II Squadron at the start of the war. The following units formed the core of the battle fleet, including the Nassau class, already described.

The four ships of the Helgoland class (22,800 tons) were the first armed with 30.5-cm cannon, of which they had twelve, plus fourteen 15-cm guns. The hexagonal arrangement was retained for the six twin 30.5-cm turrets. Speed was twenty-one knots, protection was similar to the preceding class.

The following Kaiser class (24,700 tons) had five ships. Armament consisted of ten 30.5-cm and fourteen 15-cm guns. The turret positions had now been changed—one turret on the forecastle, two turrets “en echelon” amidships, and two turrets aft in a superfiring arrangement. Armor was considerably strengthened—for example, 350-mm in the main belt and 40-mm on the torpedo bulkheads. Speed increased to twenty-two knots. For the first time, a diesel engine was planned for one of these ships, Prinzregent Luitpold, as propulsion for the central shaft. However, it took until 1917 to perfect a satisfactory diesel engine, and by that time it could no longer be installed.

One ship of the four in the next, König, class (25,800 tons) was commissioned before the outbreak of the war. The remaining three were completed by November 1914. Armament remained the same, but now all five turrets were arranged on the centerline, two forward and two superimposed aft. Armor was similar, with the torpedo bulkheads strengthened to 50 mm.

Only two of the four ships of the Bayern class (28,500 tons) were completed during the war, joining the fleet in 1916 and 1917. For the first time a main armament of 38-cm caliber was chosen. There were eight of these guns, in four twin turrets, and sixteen 15-cm cannon. Armor corresponded roughly to that of the König class, with a top speed of twenty-two knots. Further battleship designs did not get beyond the planning stage.

Armored Cruisers and Battle Cruisers

Some of the older armored cruisers had been reactivated and were still in service for reconnaissance purposes at the start of the war. Three of these were lost to mines or torpedoes very early in the conflict. Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were posted to the East Asian station at the beginning of the war; after a victory at Coronel they were sunk in the battle of the Falkland Islands on 8 December 1914. The most modern armored cruiser, Blücher, served with the battle cruisers in 1st Scouting Squadron until her loss at the battle of Dogger Bank in January 1915.

With the previously mentioned Von der Tann the German navy also undertook the construction of battle cruisers. Not privy to Sir John Fisher’s thinking, the Germans took their own path to the type, enhancing the armored cruiser’s firepower with battleship-caliber guns, with increases also in protection and speed. This progression did not accord with the ideas of Tirpitz, who did not envision armored cruisers serving in the battle line. In fact, it was a step in the direction of the fast battleship.

The next two ships, of the Moltke class (23,000 tons), were armed with ten 28-cm and twelve 15-cm guns. The additional turret was arranged in superfiring position aft. Armor and torpedo bulkheads were strengthened and speed increased to 25.5 knots. Soon after the war started the second ship, Goeben, was passed on to Turkey, where she was renamed Yavuz Sultan Selim. (She remained in Turkish service after the war and following World War II carried NATO pennant number B70 until decommissioned in 1954.)

The following Seydlitz (24,700 tons) was an enlarged and better protected Moltke. The immediately visible difference was an additional weather deck in the forecastle area. Armor (belt armor 300-mm) and torpedo bulkheads (up to 50 mm) were strengthened, with practically the same armament and a slightly higher speed (26.5 knots).

The transition to 30.5-cm caliber was accomplished with the three ships of the Derfflinger class (26,600 tons). All three were commissioned after the war broke out. Armament consisted of eight 30.5-cm and twelve to fourteen 15-cm guns. The four turrets were arranged in a purely centerline arrangement. Armor roughly approximated that of the previous class. The torpedo bulkheads were now generally 45 mm thick. Trial speed at one mile was approximately twenty-six knots. This was achieved in shallow water, due to wartime circumstances, and corresponded to twenty-eight knots in deep water. For propulsion all German battle cruisers had four-shaft systems with turbines, unlike the battleships, which always had three-shaft systems. (Up until the Helgoland class battleships all had reciprocating machinery, the following classes all having turbines.)

At the end of the war four ships of the Mackensen class (31,000 tons, eight 35-cm guns) and one ship of the Ersatz Yorck class (33,500 tons, eight 38-cm guns) were in various stages of construction. Another two Ersatz Yorcks were planned.

Light Cruisers

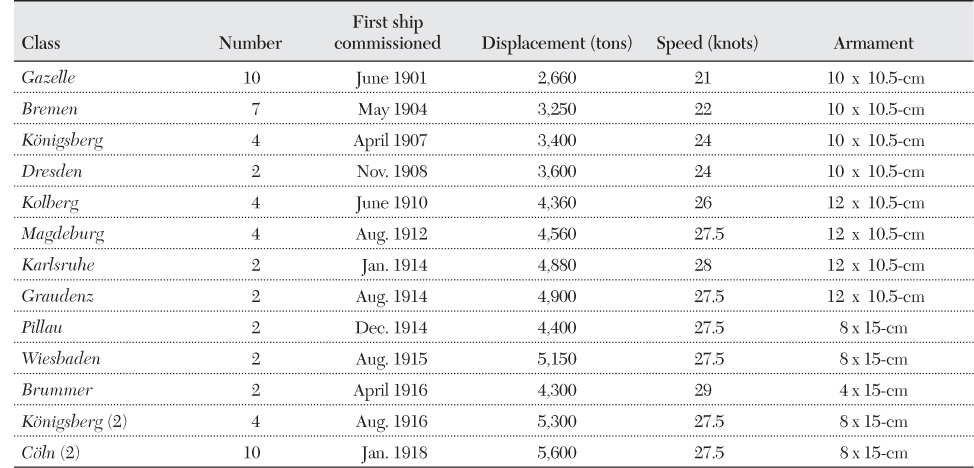

The construction of light cruisers of a unified type for fleet and colonial use started with the previously mentioned Gazelle class, whose design was consistently further developed. This, of course, inevitably led to compromises. Thus these cruisers were neither as fast nor as agile as Britain’s fleet cruisers. (See table 3.2.)

Regarding armament, the navy stuck with the 10.5-cm gun for a long time. A direct order from Tirpitz in 1913 caused the switch to the 15-cm gun. Some of the older cruisers were reequipped during the war. From the Magdeburg class onward, light belt armor and an improved bow form were incorporated. The older cruisers had a cork dam, of doubtful value, on their sides. The two cruisers Pillau and Elbing were under construction for the Russian navy at the start of the war and were completed after being requisitioned. They proved welcome reinforcements. Brummer and Bremse were built as minelaying cruisers; in addition to minelaying duties they proved highly suitable for fleet service. They were the fastest cruisers in the fleet. Outline studies for a pure fleet cruiser were carried out during the war, but none got past the drawing-board stage. Eight Cölns remained unfinished at the end of the war.

Photo 3.2. Battle cruiser Derfflinger (Peter Schenk collection)

Torpedo Boats

The high-seas torpedo boats, as previously mentioned, started with S 90. These boats were preferably funded and built in divisions of six units. Because of their small size the torpedo boats did not get names but rather letter-number designators. For the majority of the boats the letter indicated the shipyard of construction:

B |

Blohm & Voss, Hamburg |

G |

Germaniawerft, Kiel |

H |

Howaldtswerke, Kiel |

S |

F. Schichau, Elbing |

V |

Vulcan-Werke AG, Stettin. |

Exceptions to this rule were the following designations: A for small torpedo boats for coastal use, and D for division torpedo boats. The numbering of the torpedo boats with shipyard codes was done consecutively—that is, as each boat was laid down, regardless of the letter assigned. The A and D boats were numbered separately.

The size of the boats continued to increase moderately with each new series. These vessels grew from the 310-ton S 90 to the 660-ton G 197. Speed increased from around twenty-seven to approximately thirty-two knots. Armament was originally three deck-mounted 45-cm torpedo tubes and three 5-cm cannon but was later increased to four 50-cm torpedo tubes and two 8.8-cm guns. The S 125 and G 137 were the first German torpedo boats with turbine propulsion. Starting with V 161, this became standard for all boats.

Table 3.2 German Light Cruiser Classes

Note: The Lubeck of the Bremen class was the first German cruiser with turbine propulsion. Different propeller sizes and arrangements were tested with this ship. From the next two classes, only one ship each had turbines, again as a trial. Not until the Kolberg class were all cruisers equipped with turbine systems.

In 1911 the shipyard numbering scheme was restarted, with V 1 through S 24 (boats of 569 tons). The older boats kept their previous numbers but were switched to the designation T instead of their previous shipyard letter codes as new vessels with the same number sequence were commissioned. Armament and speed of these boats roughly corresponded to those of the preceding series.

The next torpedo boat series, encompassing boats V 25 through G 95, displaced 812 tons. Speed increased to thirty-six knots. Armament consisted of six 50-cm torpedo tubes and three 8.8-cm cannon (later up to three 10.5-cm Tk or Utof—the latter a quick-firing gun on an antiaircraft mount for submarine or torpedo-boat use). Two of these boats were already in service at the start of the war.

Altogether, the navy had in 1914 132 high-seas torpedo boats, or “large torpedo boats,” as they were called at that time. Two boats were at Qingdao on the East Asian station. The ten D, or division, torpedo boats and approximately seventy small torpedo boats still in service were mainly used for other purposes. Some were employed as training boats and others refitted as minesweepers, coast-defense boats, or tenders.

The series beginning with G 96 and V 125 and running through H 169 (displacement 990 tons) was intended to include forty-six boats; however, only twenty entered service. From another planned design for a series of fifty-four boats, a few were laid down, but none were completed. A special type of small torpedo boat had been designed for use off the coast of Flanders; the boats A 1 through A 113 were planned, in three series. However, from the last series twenty-one were never completed. Many of these boats also served as minesweepers. The series from B 97 to V 100 and from B 109 to B 112 resulted from a yard design for Russian destroyers. These ships had a displacement of 1,350 tons and a speed of up to thirty-seven knots. Their armament consisted of six 50-cm torpedo tubes and four 8.8-cm Tk (later four 10.5-cm Tk). Four destroyers under construction for Argentina were confiscated and became G 101 to G 104 (displacement 1,116 tons). They were capable of reaching thirty-three knots, with armament corresponding to that of the previously mentioned destroyers. However, from a series of large destroyers, only S 113 and V 116 entered service. These ships displaced 2,060 tons and were fast, making up to thirty-seven knots. Armament consisted of four 60-cm torpedo tubes and four 15-cm Utof guns.

Weapons: Gunnery

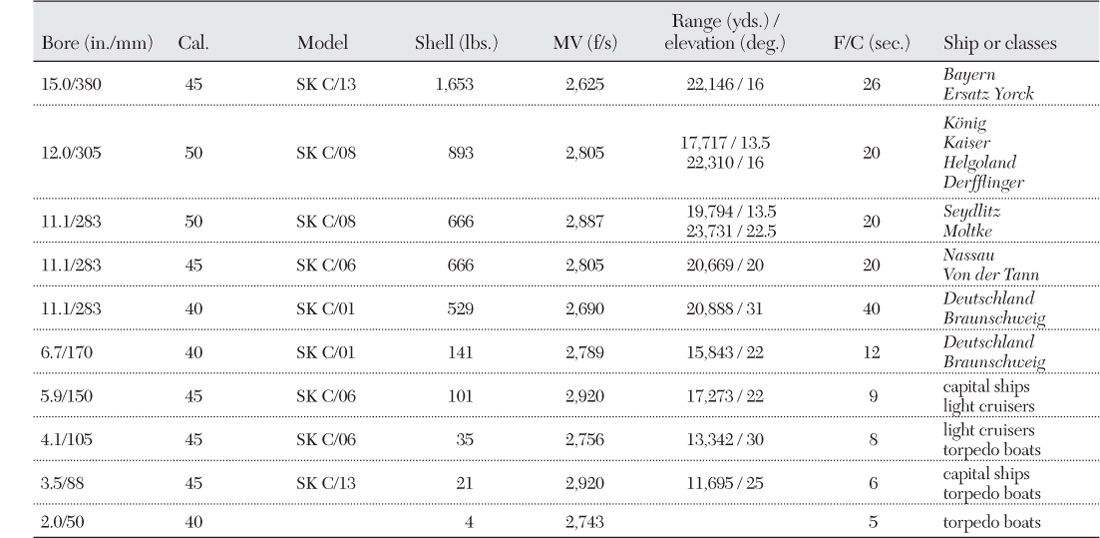

Since Krupp delivered the first guns to the Prussian army in 1860, this company had become the most important supplier of artillery in Germany. Therefore the navy’s guns were also from that firm. The fundamental structure of the gun barrels consisted of an inner tube, with shrunk-on tubes and hoops, and an outer casing. The process of shrinking-on tubes in a heated condition produced a bias stress on the inside. Such a barrel could better withstand the strong internal pressure of firing. The breech was a sliding-wedge breechblock. For large guns the breechblock’s orientation was horizontal. Large guns also used a two-part propellant charge; the forward charge was in a silk bag, the main charge in a brass casing. The warheads of armor-piercing shells were hardened, with mild steel caps. This improved penetration when hitting at an angle. (See table 3.3.)

With the increase in battle distances and firing ranges, effective fire control became imperative. An important step toward achieving this was the introduction of stereoscopic range finders. These were first offered by Carl Zeiss in 1905, and from 1908 they were generally installed on German warships. On capital ships the turrets were equipped with the six-meter base model on 28-cm turrets and an 8.2-meter base on 38-cm turrets. Further important elements of the fire-control system were telescopic sights, the Abfeuergerät, and analog fire computers. The Abfeuergerät worked with gyros and indicated the right moment to fire in relation to the ship’s roll. An analog fire-control computer tracked and accounted for distances and changes in the relative locations of the fighting ships. Synchros coupled the elements of this system with each other.

Centralized fire control with range measurement from the foretop was not available until after the battle of Jutland. The lack of this capability had an adverse effect if turret commanders could not take the target’s bearing due to poor visibility. After Jutland the Germans worked to further develop their fire-control system.

Submarine Warfare

Offensive

Doctrine

Before World War I, German U-boats were designed and their crews trained exclusively to attack enemy warships. German operational tactics called for submarines to establish watch positions and scouting lines for harbor and coastal defense or to find the enemy in the open North Sea. When the enemy was located in a favorable position for an attack, boats were to engage submerged, firing torpedoes at a target angle of ninety degrees (that is, from abeam of a target) in order to bring all forward and aft tubes to bear. However, the relatively slow speeds of the U-boats compared with modern ships of the line, as well as their small radius of observation, made valid attack opportunities rare. Radio communication was still in its infancy, making controlled operations almost impossible. Consequently, expectations regarding U-boat operations were rather low within the higher circles of the German navy. The focus was entirely fixed on a decisive engagement between the opposing battle fleets.

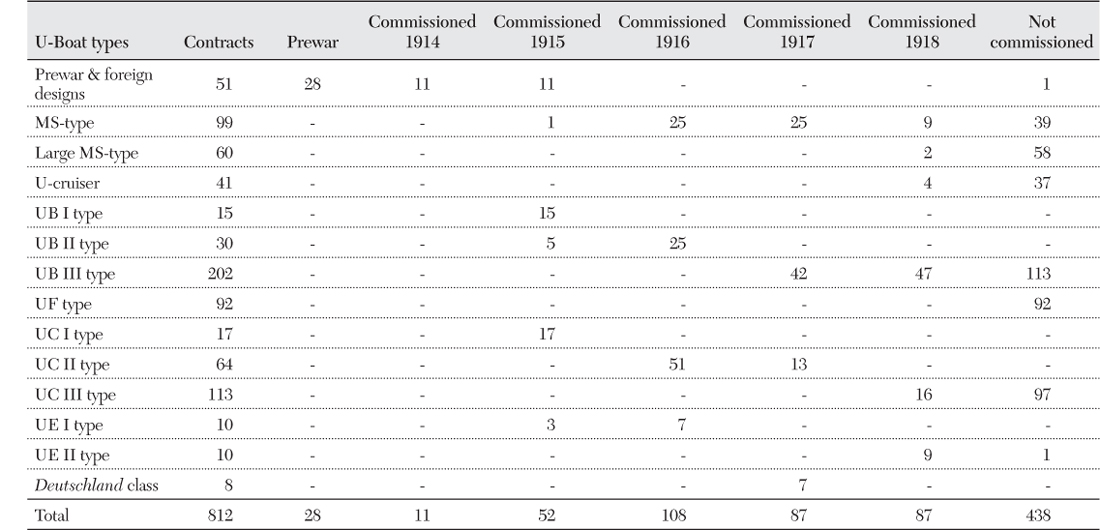

Germany started the war with twenty-seven submarines in commission and a further fourteen under repair or in various stages of construction. The recently commissioned diesel submarines U 23 through U 28 were still working up, while the oldest boats (U 1, U 3, and U 4) were already relegated to training duties in the Baltic. With new fleet-type U-boats taking seventeen to twenty-four months to build, a rapid increase in numbers was unlikely. Therefore in autumn 1914 a total of thirty-two quickly constructed but small boats of the UB I torpedo and UC I minelaying types, displacing only 150 tons, were ordered for use in the eastern part of the English Channel from the newly captured bases on the Belgian coast. To differentiate the new designs from the larger, fleet-type submarines, these new U-boats were somewhat confusingly designated in different series, with letters UB or UC and numbers starting from one, as in UB 1 and UC 1.

In a similar manner, ten Type UE I medium-sized fleet minelayers were ordered for distant operations. Production of the larger but ultimately more capable mobilization (Ms-Type) fleet torpedo submarines continued on a small but steady scale.

As a continuation of the first small-boats program, a new building program was begun in 1915 for 260-ton UB II torpedo-carrying U-boats, in combination with 420-ton minelaying subs of the UC II type. After the U-boat war had been scaled down in September 1915 following repeated American protests, mining operations were seen as more useful employment for the submarines. However, the still limited size and endurance of the new boats restricted their operational use to the North Sea, the English Channel, and areas within reach of German bases in the Mediterranean. With unconditional antishipping operations by German U-boats again halted in summer 1916, the German Admiralty came to favor the construction of large U-cruiser types to allow for operations according to prize regulations in the open Atlantic and other far-distant areas.

In parallel with the U-cruiser program the building of new medium-sized UB III torpedo-armed boats was begun to supplement the larger fleet U-boats, especially in the Mediterranean. Also, the few remaining UE I minelayers were followed by the much larger Type UE II boats. In the final phase of the war, U-boat construction was concentrated on a few main types. Wartime experience led to the design of the new 350-ton UF-Type boats, which were intended for quick production at small yards not hitherto involved in building U-boats, and the Type UC III, as an improvement to the previous UC II design. The latter two types, however, came too late to see operational service during the war. Tables 3.4 and 3.5 show the slow and often erratic course of the German U-boat building program during the war years.

In 1891 the 450-mm-diameter torpedo model C 45/91, with a speed of thirty-two knots, and the 350-mm, twenty-nine-knot C 35/91 were introduced as the German navy’s first modern torpedoes. They were still useful twenty-five years later, when employed by German submarines during the First World War. After several steps the German navy in 1907 adopted the G/7 torpedo for battleships, with a diameter of 500 mm, a length of seven meters, and a range of 9,300 meters at twenty-seven knots, or four thousand meters at thirty-five knots. The six-meter-long G/6 was intended for smaller ships and submarines. It had a range of 8,400 meters at twenty-seven knots and 3,500 meters at thirty-five knots. By 1914 the 500-mm, pressure-driven G/6, carrying a contact-fused 160-kg explosive warhead and fitted with a plus-or-minus-ninety-degrees target-angle director, had become the standard torpedo on board boats from U 19 onward. Further developments shortly before the end of the war included the H/8 for the Baden-class battleships, with a caliber of 600 mm and a range of 12,000 meters at thirty knots; the electrically driven E/7; and a magnetic detonator. For the torpedo planes the C 45/91 was used. Production of torpedoes took place at BMAG, the navy-owned Torpedowerkstatt Kiel, and also at the Whitehead factory, which had been moved from Fiume to St. Pölten in Austria.

Photo 3.3. Light cruiser Ariadne (Peter Schenk collection)

Table 3.4 U-Boat Building Contracts and Overall Deliveries, 1906–18

* Includes the privately contracted civilian transport U-boats Deutschland and Bremen, with the former taken over in 1917 as U 155, while Bremen was lost in 1916 in its civilian role.

** Includes six privately contracted civilian transport U-boats taken over before completion in 1917 by the German navy as U-cruisers U 151–U 154, and U 156–U 157.

Table 3.5 German U-Boat Types Contracted and Delivered, 1906–18

With the main focus of German naval activity on battle-fleet and torpedo-boat operations, antisubmarine warfare consisted mainly of the heavy mining of coastal waterways in the North and Baltic Seas. This worked well for much of the war, as the threat from mines prevented allied submarines from operating close to German-held coastlines. Even the threat presented by the transfer of a British submarine flotilla to the Baltic in late summer 1915—to operate against the iron-ore traffic from Sweden to Germany—was quickly brought under control, following some initial losses. In addition to mines, great use was made of nets and barriers to close vital passages and harbors to submarines. Sometimes the nets were armed with small explosive charges. During the large-scale German amphibious operations against the Estonian island of Ösel, the landing area in Tagga Bay was completely sealed off with a twelve-kilometer-long net barrier to protect the supporting battle-fleet units against submarine attacks.

Early in the war, detection of submerged submarines was almost impossible. From 1915 onward primitive listening gear provided limited means of detection. Antisubmarine weapons included towed nets and paravanes carrying explosive charges that detonated on contact. Depth charges came into use from 1916 but were ineffective due to the rare opportunities for attack. In the absence of purpose-built ships, advanced antisubmarine location gear or weapons, or specially trained personnel, antisubmarine operations were normally conducted by converted fishing vessels, minesweepers, and old torpedo boats—these being used as escorts for fleet units and merchant ships in areas of known enemy submarine activity. Given this background, it is not surprising that during the entire war only two allied submarines fell victim to German surface warships, both sunk by gunfire. German U-boats became the most successful submarine killers but usually encountered or attacked their allied counterparts as targets of opportunity while on their own patrols.

Doctrine

In the event of war the German navy planned to establish defensive mine barrages off its North Sea bases and in the entrances to the Baltic, as well as to stage offensive minelaying operations along the British east coast. The defensive mine barrages were laid in the war’s first days. In August 1914 a first—and very risky—offensive minelaying operation was carried out in the Thames estuary by the twenty-knot auxiliary minelayer Königen Luise. The ship was sunk by the cruiser Amphion and an accompanying destroyer flotilla, but later Amphion herself sank on one of Königen Luise’s mines, which would also eventually claim four minesweepers and eight merchant vessels. Subsequently, minelayers Nautilus and Albatros conducted successful missions off the British east coast. However, a dangerous operation in the Downs by four torpedo boats led to their destruction. The armed merchant cruiser (AMC) Berlin had better luck in October 1914, managing to slip through the British patrols and lay two hundred mines off the west coast of Scotland near Lough Swilly, where part of the Grand Fleet was exercising. The modern battleship Audacious was lost on one of her mines.

The AMC Meteor laid mines off the port of Arkhangelsk that accounted for twelve merchant vessels and a minesweeper. On her second sortie, Meteor mined the Moray Firth on the east coast of Scotland. During this mission she was discovered by the British AMC Ramsey, which Meteor was able to sink, but on her return four British cruisers hunted down the German ship off Jutland. Light cruisers laid minefields during the raids of battle cruisers against the British east coast. However, by mid-1915 only submarines were able to mine the waters around the British Isles.

Despite the Russian defeat in East Prussia in 1914, the advance in the East was slow. The Russian navy remained mostly on the defensive, behind mine barrages protected by coastal batteries. German cruisers made sorties to mine and thereby block the port of Libau, where British submarines were based. After the armored cruiser Friedrich Carl hit two mines and sank during one such mission, these operations were stopped. In August 1915 two battleships and two cruisers entered the Bay of Riga and shelled Pernau. The Russians too laid offensive mine barrages off Memel, later off East Prussia and east of Bornholm, and even one barrage north of Rugia in the winter of 1914/15. These mines accounted for several ships lost or damaged. In 1916 there was one smaller Russian mining operation near Libau, which Germany had occupied in May 1915, and none thereafter.

In 1914 Germany had only two purpose-built minelayers, the Nautilus and Albatros, each capable of twenty knots. In 1916 fast minelayers Brummer and Bremse (twenty-eight knots) were commissioned, and these ships performed well. A variety of fast passenger vessels and ferries served as auxiliary minelayers.

At the beginning of the war the German navy had forty-five converted torpedo boats organized into three minesweeping divisions. Soon specialized minesweepers were ordered: the coal-fired M-boats, of about five hundred tons and sixteen knots, plus F-boats, motor minesweepers of twenty tons and ten knots, for coastal waters. In 1918 these were joined by the FM-boats, two hundred tons and fourteen knots. In all, 145 M-boats were commissioned, of which twenty-seven were lost to mines and three to other causes. In addition, fifty-seven F-boats and six FM-boats were built. Numerous fishing craft also acted as auxiliary minesweepers.

In 1877 Germany bought its first mines, of the anchored C/77 type, which had a 40-kg charge with potassium ignition. The subsequent C/05 and C/06 had 80-kg charges. New-standard mines were introduced in 1912 with the EMA (150-kg charge) and EMB (225 kg). U-boat minelayers carried one of two basic moored-mine types (UC 120 or UC 200), in each case with hundred-meter mooring cables. Measuring eighty centimeters in diameter, they differed in length according to the size of the charge, as indicated by the name (120 kg for the UC 120, 200 kg for the UC 200). These mines were dropped either from flooded vertical mine chutes penetrating the pressure hull (UC-type minelayers) or from horizontal mine-ejection tubes at the stern, loaded from a dry mine storage compartment inside the pressure hull (UE-type minelayers). During the war, wet-stored mines showed a tendency to explode prematurely, which caused several U-boat losses. In the course of the conflict special 50-cm torpedo mines were developed to be ejected from the torpedo tubes of normal U-boats (the P-Mine, length about three meters, and TEKA-Mine, length about two meters, each carrying a 100-kg warhead).

The German navy laid 45,000 mines during the war. The dreadnought Audacious, three predreadnoughts, four cruisers, one monitor, thirty destroyers, nine torpedo boats, and a large number of minor craft were lost on these mines. Mines also caused an estimated 10 percent of allied merchant shipping losses.

Doctrine/Capabilities

The Kaiserliche Marine did not consider the problem of transporting troops and their equipment other than port garrisons. Three Seebataillone—battalions of naval infantry—were formed but not trained for beach assault. There was, however, cooperation with the army engineer corps, whose commander, General Colmar von der Goltz, ordered developmental work on the landing of troops on open beaches, holding a first exercise in 1900. At the beginning of the war one engineer battalion was trained for such operations, equipped with inflatable rubber boats and unpropelled landing craft to transport horses, guns, and small vehicles. These craft could be towed from the transports by motorboats and pulled on cable lines through the surf.

One company was used to help cross the Danube at various places in October 1915, November 1916, and January 1917. A bigger operation was carried out in October 1917, the landing of a reinforced division on the Russian Baltic island of Ösel. After the first assault, under a curtain of covering fire from no less than eleven battleships, twenty transport steamers were unloaded by landing boats and barges, unmolested by enemy submarines due to a protective net barrage that had been laid the same day.

Helgoland was heavily fortified, with four 305-mm twin turrets and four single 210-mm guns. There was also Battery Friedrich August on Wangerooge with six 305-mm guns, Battery Grosser Kurfürst at Pillau with four 280-mm guns, and medium batteries at Borkum, Norderney, Sylt, and Schillig, near Wilhelmshaven. To protect the submarine ports of Ostend and Zeebrugge against shelling by British monitors, the coastal artillery emplaced five batteries, with guns up to 280-mm caliber, by March 1915. In autumn 1915 Battery Tirpitz was put into service, with four 280-mm guns and a range of thirty kilometers. In spring 1916 Battery Kaiser Wilhelm II became operational, with four 305-mm guns ranging to thirty-seven kilometers, which prevented further shelling of the bases. In all, twelve heavy and eleven medium batteries were mounted in Flanders.

Another means to counter the British monitors involved wire-controlled unmanned explosive motorboats (Fernlenkboote). Two were sunk by artillery in 1916 while trying to attack monitors M 23 and Erebus, but one destroyed part of the mole at Nieuport.

Aviation

The value of this new weapon was recognized when World War I was still in its infancy. The German naval air arm began the war with one airship at Hamburg, six seaplanes at Helgoland, two airships in the Baltic, and four seaplanes at Kiel. The airships of the Marineluftschiffs-Abteilung, founded in 1912, soon proved their value in long-range reconnaissance over the North Sea and Baltic. In good weather three airships could cover the German Bight. The seventy-eight naval airships carried out 1,148 reconnaissance sorties during the war. Airships could also spot minefields and mark them with buoys. They were also used with army airships for bombing raids. The 197 tons of bombs dropped mainly on London from 1915 to 1917 in two hundred night raids had a great psychological effect, until these operations had to be stopped due to mounting losses.

Nordholz, near Cuxhaven, was the main airship base and headquarters, with ten hangars. Other bases were at Hage, Ahlhorn, and Tondern on the North Sea coast, and at Seddin (near Stolp), Seerappen (near Königsberg) and Weinroden (near Libau) in the Baltic. Airships were also deployed to the Black and Adriatic Seas. In September 1917, LZ 104 attempted an epic journey from Bulgaria to East Africa loaded with supplies for the isolated troops there. But near Khartoum the airship had to turn back when a message arrived that German forces had had to withdraw from the stipulated landing place. The zeppelin returned to its base after a round trip of six thousand kilometers.

Naval aircraft were concentrated in the I Marineflieger-Abteilung (MFA) at Kiel-Holtenau and II MFA at Wilhelmshaven. In September 1915 these detachments were renamed Seeflieger-Abteilungen (SFA). Like the Marineluftschiffs-Abteilung, they reported to the Befehlshaber der Marine-Luftfahr-Abteilungen (BdL), Rear Admiral Otto Phillip. In December 1916 the naval airships got their own commander, known as the Führer der Marineluftschiffe (FdL), a title held by Commander Peter Strasser until his death in August 1918. The BdL was renamed as Befehlshaber der Marine-Fliegerabteilungen (BdFlieg) and then in July 1917 Marine Flugchef.

Naval planes were deployed at thirty-two sea bases and seventeen air-fields on the Baltic and North Sea coasts, in Belgium, on the Black Sea, and in the Mediterranean. A total of 1,478 sea and land planes were taken into service, of which 673 were frontline seaplanes and 191 frontline land-based aircraft. Personnel numbered in 1918 some 16,122 men, of whom 2,116 were pilots and aircrew.

The planes of the era were lightly armed and could only carry small bombs. Thus their main role was reconnaissance. In spite of this, German naval aircraft shot down 270 enemy planes and two airships, and they sank one Russian destroyer, three submarines, four motor torpedo boats, four merchant vessels, and twelve minor craft.

Much effort was devoted to the development of torpedo planes, seen as the only means to destroy larger ships from the air. A special command for this branch of the air arm was formed at Flensburg under Commander Konrad Goltz. A first, unsuccessful, attack was flown against Russian warships in the Gulf of Finland on 12 September 1916. The first “kill” was the British cargo ship Genua in the English Channel on 1 May 1917. Another steamer, Storm of Guernsey, was sunk on 9 July 1917 in the same area. In all, during eleven missions twenty-eight torpedoes were launched and six hits achieved. In the summer of 1917 these torpedo planes successfully mined Russian Baltic ports using mines developed for submarines.

At the beginning of the war the Marineflieger-Abteilung ordered seaplanes for fighter and reconnaissance purposes. For the fighter role the Hansa-Brandenburg KDW seaplane was introduced in 1916, and sixty were built. Forty of the Rumpler 6B1 seaplane fighters were also taken into service starting in 1916. In the same role, 114 of the Albatros W 4 type were built from 1917 on. In addition, land-based fighters were found necessary to protect bases from enemy air attacks, and the Pfalz D III was ordered. The torpedo squadron used the Freidrichshafener Flugzeugbau FF 41 and the Gotha WD 7; both were two-engined float biplanes and were also used in the reconnaissance and bomber roles.

The fifty-nine German naval airships were mostly built according to the zeppelin design, with aluminum ribs, but there were also two Parseval (blimps) and nine Schutte-Lanz types with timber ribs. Hydrogen-gas volume varied between 56,000 and 69,000 cubic meters and payload between forty and fifty tons. Five or six Maybach engines gave airships a speed of 100 to 130 km per hour. The airships proved very efficient at long-range reconnaissance, as they could stay in the air for many hours. From 1916 trials were undertaken for launching from airships radio- or wire-controlled torpedoes attached to gliders, but this came to nothing.

Shipboard aviation started early, with the conversion of two cargo vessels into seaplane tenders. Answald and Santa Elena were commissioned for the High Seas Fleet in mid-1915 as Flugzeugschiff I and II. A third, Oswald, was converted in 1918, and a fourth, Glyndwr, had been used as a training vessel since 1914. The aircraft used on board were Friedrichshaftener Flugzeugbau types, mainly the FF 33. One cruiser, Friedrich Carl, received two planes in September 1914 but was mined and sunk in the Baltic soon after. The light cruiser Stuttgart was rebuilt with a hangar for two planes in 1918. The armed merchant cruiser Wolf, battle cruiser Derfflinger, light cruiser Medusa, and several mine-destruction vessels made good use of embarked aircraft. An innovative project to convert the unfinished liner Ausonia into an aircraft carrier, with a hangar deck for wheeled fighters and another below for two-engined torpedo planes, could not be started before the war ended.

WAR EXPERIENCE AND EVOLUTION

Wartime Evolution

Surface Warfare

The war had come much earlier than Tirpitz had wished, and in summer of 1914 the German fleet in the North Sea was inferior to the Royal Navy by a factor of one-third. In the first phase of the war the navy hoped for an early defeat of the allied forces in northern France. Having in mind a short war, the High Seas Fleet, under Admiral Friedrich von Ingenohl, remained in port awaiting the actions of the British Grand Fleet. During this time German cruisers were active in the Pacific and South Atlantic, drawing away three Grand Fleet battle cruisers to deal with the threat they presented. This effect had been expected by the Germans but was not exploited. Another strategic option would have been to attack the supply and transport of the British Expeditionary Force in the English Channel, but this was deemed too risky.

On 28 August, the British raided the cruisers supporting the patrols off Helgoland, after British submarines had observed a daily routine of torpedo boats being escorted to their night patrols by cruisers. The British appeared with five battle cruisers and eight cruisers, plus destroyers, sinking the German cruisers Mainz, Cöln, and Ariadne, as well as a torpedo boat. German battle cruisers sent to intervene arrived too late. This type of hit-and-run battle would thereafter be repeated often. German battle cruisers shelled Yarmouth on 3 November 1914 and struck Hartlepool, Whitby, and Scarborough on 15 December 1914. On 24 January 1915, the next German raid—four battle cruisers under Admiral Franz Ritter von Hipper against the fishing fleet at Dogger Bank—was intercepted by a squadron of five British battle cruisers under Admiral Sir David Beatty. A running fight developed, with the British chasing the Germans, in the first battle between examples of this new class of capital ship. Seydlitz was hit, burning out her two aft turrets, and Blücher took a hit that affected her machinery, so that the ship fell behind and was sunk. On the British side, Lion was heavily damaged. The commander of the High Seas Fleet, having remained in port with the battleships, was now replaced. Admiral Hugo von Pohl became the new commander, with an admonition to be more cautious.

Pohl died in February 1916, and Admiral Reinhard Scheer, an energetic leader, gained command. The raids on the British east coast were resumed on 25 April 1916, with the shelling of Lowestoft and Yarmouth. Scheer expected his next sortie to generate a major battle, and when he sailed from Wilhelmshaven bound for the Skagerrak on the morning of 31 May 1916 he brought with him the six predreadnoughts of II Squadron. Deciphered signals had informed the British of this sortie, and they also went to sea in full force, with a superiority of about a third.

The battle-cruiser squadrons, sailing in advance of their respective fleets, clashed first. A running fight developed, with the Germans under Rear Admiral Hipper retreating toward Scheer’s battle fleet. Indefatigable and Queen Mary were both hit and fatally exploded. The four fast battleships of the Queen Elizabeth class that followed prevented further losses. Meanwhile, Scheer, with his sixteen battleships and six predreadnoughts, came up to assist Hipper and engaged the Queen Elizabeths. The three battle cruisers of the British third squadron approached the German battle cruisers, and another British battle cruiser, Invincible, suffered a vital hit and exploded. On the German side, Lützow had to be abandoned. Finally the commander of the Grand Fleet, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, with twenty-four battleships, arrived on the scene and tried to destroy the leading German ships by crossing the T of Scheer’s formation and concentrating fire on the head of the latter’s line. Scheer reacted with a surprising maneuver, the simultaneous turning of each ship on the spot, which allowed the Germans to avoid the danger and break contact. After another turn to east the battle fleets met once again, and the German battle cruisers at the head suffered badly. German torpedo-boat attacks forced the British line to turn away, and both fleets separated in the night to steam south. Jellicoe hoped to resume the battle in the morning but did not succeed in reestablishing contact; the High Seas Fleet reached port.

The battle had not forced a decision. The blockade had not been lifted, and it was felt in Germany all the more. Tactically the battle of Jutland demonstrated how difficult it was to command the great fleets at the given gun ranges, in conditions of poor visibility, and with faulty communications.

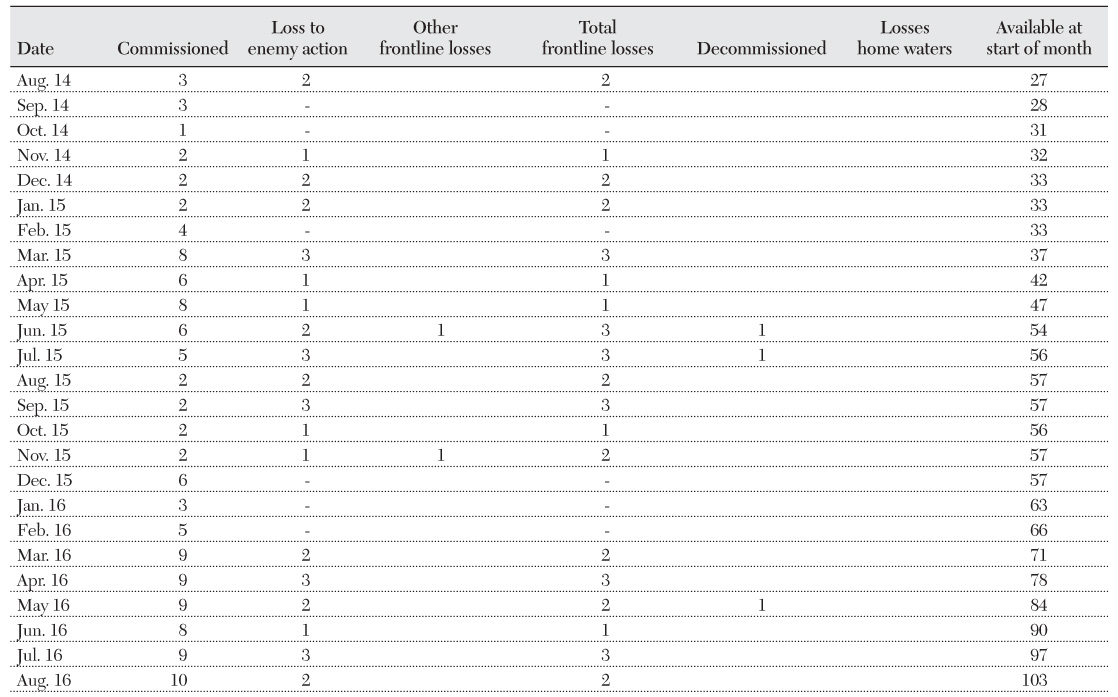

Submarines

In the early months of the war, German U-boats were mainly employed on single patrols or scouting lines, in the North Sea, or against troop transports in the eastern English Channel. In October 1914, U 20 rounded Britain for the first time. Wartime conditions demonstrated that longer patrols, lasting by July 1915 up to twenty-five days, had no negative effect on crews or material.

Actual results during the first six months of the war nevertheless confirmed pessimistic prewar expectations regarding the efficiency of submarines in operations against enemy fleets. Although the destruction of three old British armored cruisers in the North Sea on 7 September 1914 by U 9 made its commander, Otto Weddigen, a national hero and boosted German morale, the sinking of a total of ten outdated warships in exchange for the loss of seven submarines during that period had no real impact on British superiority at sea. However, the appearance of German U-boats all around Britain did markedly affect the disposition and operations of the British Grand Fleet, due to the fear of substantial losses in possible encounters. As a result, the strategic impact of German U-boats in the early phase of the war greatly exceeded their tactical success.

In November 1914 the British government declared a total naval blockade against Germany and its allies. Spurred by this flagrant violation of international law and the dawning apprehension—after the transition to trench warfare—that the conflict would not be over in a matter of months, the German Admiralty gradually came to adopt the idea of a counterblockade in retaliation. Under the military and political situation existing at the beginning of 1915, German U-boats offered the only option available to enforce such a blockade in the waters around France and Britain. On 4 February 1915 Germany declared the waters around Britain a war zone, effective from 18 February, where all enemy merchant shipping was subject to attack. In accordance with the British precedents, prewar legal restrictions on this kind of warfare were thereafter successively dropped, especially after the British Admiralty lifted the nonbelligerent status of British and allied merchant ships by arming them and instructing their masters to attack U-boats whenever possible.

Exceeding the German Admiralty’s expectations, the few U-boats available in early 1915 were rather successful in their new role. By the end of April 1915 seventy-one merchant ships, comprising 155,000 gross tons, were sunk. Quickly appreciating this new threat to their war effort, the British government started a widespread public propaganda campaign against German U-boats and their crews, caricaturing them as perfidious and bloodthirsty pirates. At the same time, diplomatic steps were taken to bring the neutral countries in Europe and overseas, especially the United States, in line with the war interests of the Entente. Due to the strong cultural and economic links of its political and industrial elites with Britain and its empire, the U.S. government soon sided with the British, while openly insisting on the rights of neutral states, including free trade even within the declared blockade zone. This was evidently only in favor of allied war aims, since no American ship ever tried to sail for German ports during the war. German diplomatic countersteps failed to influence the American position.

Following the sinking of the British passenger liner Lusitania, carrying many U.S. citizens as well as war material, inside the German blockade zone by U 20 on 7 May 1915—resulting in heavy loss of life, including 110 Americans—the U.S. government protested strongly against German submarine-warfare policy. Since the political opinions held by the kaiser and his government still dominated military views at this time, in the following months the German Admiralty was forced to scale back its successful U-boat campaign in order to avoid further tension with the U.S. government. On 19 August 1915 the Arabic incident, involving the loss of eight U.S. citizens, triggered further diplomatic protests from the Americans. Eventually, on 18 September 1915, the German Admiralty stopped all attacks against trading vessels west of Britain and in the English Channel, reverting to prize regulations in the North Sea. Except in the Mediterranean theater, the military use of U-boats in the months thereafter was mainly confined to mining operations and attacks against naval vessels.