DOL issued the proposed regulation in 1988, it has never been finalized.

DOL issued the proposed regulation in 1988, it has never been finalized.Business valuation normally occurs in context: a specific value or range of values in a given set of defined parameters that, among other factors, include the legal universe in which the value is being considered, the organization of the business, and the particular rights and responsibilities of the ownership stake within that business, all as of the date of the valuation.

Identifying the correct definition of value in the legal context is a crucial beginning step in an appraisal. The belief that “value lies in the eye of the beholder” is not helpful when there is a legal need for a definition of value. Value is defined differently in different legal contexts, and the quest for the appropriate definition in any particular legal context can be difficult.

The lawyer and appraiser should agree on the definition of value at the outset, and the definition should be included in the written assignment. It is best to define and cite the source of the definition and, if appropriate, to include those details in a buy-sell or arbitration agreement. The valuation practitioner can bring experience to bear in helping the lawyer at this step. However, ultimately the definition of value is a legal question must be based on the law that pertains to the specific valuation.

It is often a shock to some lawyers and their clients to learn that there may be multiple definitions of value for the same property at the same time and that one definition may legitimately lead to an amount more than twice as much as another definition. For example, the phrase “fair market value of these shares” is frequently found in buy-sell agreements. Usually, the minority parties assume that “fair market value” means a proportionate share of the value of the enterprise as a whole. When the triggering event occurs, they are surprised to find that the term implies discounts for minority interest and lack of marketability, and those discounts sometimes total as much as 50 percent.

If an expert’s report, methodology or testimony does not follow the pertinent legal definition of value, the judge may disallow them.1

The two most common expressions of value found in U.S. statutes are fair market value and fair value. Other significant terms are market value, true value, true cash value, intrinsic value, investment value, and marital value as well as other definitions. Often opinions will not define the term as it is used or include authority or precedent for its use.

Other than fair market value and fair value, business appraisers and investment bankers will also frequently use investment value and intrinsic, or fundamental, value. These two terms are often found in court opinions but, again, usually without definition.

In the United States and Canada, the most widely recognized and accepted standard of value is fair market value. It is the standard that applies to most U.S. federal and state tax matters, including estate taxes, gift taxes, inheritance taxes, income taxes, and ad valorem taxes. It is also the legal standard of value in some other valuation situations, primarily in those involving taxes. The Treasury regulations define the fair market value of a business interest as “the net amount which a willing purchaser, whether an individual or a corporation, would pay for the interest to a willing seller, neither being under any compulsion to buy or to sell and both having reasonable knowledge of relevant facts.”3

There is general agreement that the definition implies that the parties have the ability—as well as the willingness—to effectuate this hypothetical cash transaction. The “market” in this definition can be thought of as all the potential buyers and sellers of like businesses or professional practices.

In the legal interpretations of fair market value, the willing buyer and willing seller are hypothetical persons, dealing at arm’s length, rather than any particular buyer or seller. In other words, a fair market value price would not be influenced by special motivations not characteristic of a typical buyer or seller. (In Canada, however, fair market value may include the value of synergies with a particular buyer.4)

However, while the fair market value concept assumes an open and unrestricted market, it does not preclude identifying groups of willing participants. On the contrary, the valuer should be able to identify categories of willing purchasers. The analyst also cannot ignore the position of the seller, who is assumed to be willing to sell under conditions that exist as of the valuation date.

Fair market value also assumes prevalent economic and market conditions at the date of the particular valuation. The concept of fair market value means the price at which a transaction could be expected to take place under conditions existing as of the valuation date. In other words, the fair market value buyer is looking for the best risk/reward relationship available in the market at a given time.

The terms market value and cash value are sometimes used interchangeably with fair market value. Real estate appraisers generally use the term market value rather than fair market value. The Appraisal Foundation gives the most useful definition of market value; as defined by the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice (USPAP), market value is virtually synonymous with fair market value as defined in the Treasury regulations.5

Judge David Laro, in a U.S. Tax Court decision, articulated the following as some guiding principles regarding the estimation of fair market value:

1. The willing buyer and the willing seller are hypothetical persons, rather than specific individuals or entities, and the characteristics of these hypothetical persons are not necessarily the same as the personal characteristics of the actual seller or a particular buyer.

2. Fair market value is determined as of the valuation date, and no knowledge of unforeseeable future events that may have affected the value is given to the hypothetical persons.

3. Fair market value equals the highest and best use to which the property could be put on the valuation date, and fair market value takes into account special uses that are realistically available due to the property’s adaptability to a particular business. Fair market value is not affected by whether the owner has actually put the property to its highest and best use. The reasonable, realistic, and objective possible uses for the property in the near future control the valuation thereof. Elements affecting value that depend upon events or a combination of occurrences which, while within the realm of possibility, are not reasonably probable, are excluded from this consideration.6

It is generally understood that fair market value is a value in cash or cash equivalents (as indicated in the Appraisal Foundation definition of market value) unless otherwise stated.

The expression fair value is an excellent example of ambiguous terminology used in commercial appraisal. Context is crucial to understanding the concept. In the context of a standard of value in business valuation, fair value is a term found in state statutes governing dissenting stockholder and minority oppression actions. Its meaning is quite different from the term as used in generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), where until recently fair value and fair market value were used almost interchangeably.7 Courts have given very different interpretations to the term fair value as a statutory business value standard.

Courts apply a fair value standard in cases in which the aggrieved party alleges he or she is being forced to accept less than adequate consideration for stock following a merger or sale of the business. Here, the aggrieved party seeks to enforce his or her right to have his or her shares appraised and to receive fair value in cash.8

Revisions made to the Model Business Corporation Act of 1950 and adoption of the same, in part or in full, by 35 states has led to uniformity before the 1984 revision and to its being called the Revised Model Business Corporation Act (RMBCA). Prior to 1999, the RMBCA defined fair value as follows:

The value of the shares immediately before the effectuation of the corporate action to which the shareholder objects, excluding any appreciation or depreciation in anticipation of the corporate action unless exclusion would be inequitable.

In 1999, the definition changed to the following:

“Fair value” means the value of the corporation’s shares determined:

(i) immediately before the effectuation of the corporate action to which the shareholder objects;

(ii) using customary and current valuation concepts and techniques generally employed for similar businesses in the context of the transaction requiring appraisal; and

(iii) without discounting for lack of marketability or minority status except, if appropriate, for amendments to the articles.

Although a majority of states adopted the pre-1999 RMBCA definition,9 only a few of the states have adopted the 1999 version.10 A minority of states that adopted the pre-1999 definition did so without the “unless exclusion would be inequitable” phrase11; other states omit this phrase but, in addition, add a clause that states that all relevant factors should be considered in determining value.12 Florida and Illinois use a hybrid of the pre-1999 and 1999 definitions.

There is no clearly recognized consensus about the definition of fair value in the context of dissenting shareholder statutes.13 However, the judicial precedents of most states certainly have not equated it to fair market value. When a situation of actual or potential stockholder dissent arises, it is important to carefully research the legal precedents applicable to each case and to take note of the date.

The term fair value is also found in the dissolution statutes of those states that have such statutes (for example, California Corporations Code Section 2000). An increasing number of states have enacted such statutes in recent years. Under these statutes, stockholders can trigger a corporate dissolution under certain circumstances. The company can avoid dissolution by paying the stockholders the fair value of their shares. Even within the same state, however, a study of case law precedents does not necessarily lead one to the same definition of fair value under a dissolution statute as under that state’s dissenting stockholder statute.14 The term fair value in the context of state statutes is more extensively discussed in the chapter on shareholder partner disputes.

In summary, fair market value is a willing buyer/willing seller standard, whereas fair value does not necessarily assume a “willing” seller and/or a “willing” buyer.

The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) has another definition of fair value. Here, the term is used for financial reporting purposes—specifically, to report the fair values of certain assets and liabilities appearing on financial statements.

The fair value definition was promulgated in the Statement of Financial Accounting Standards (SFAS) 157.16 It is effective for financial statements issued for fiscal years beginning after November 15, 2007, and for interim periods within those years.

The SFAS 157 definition is as follows:

The price that would be received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date.

The important feature of this definition is that it is an exit price, not the price that would be paid to acquire the asset or to assume the liability (an entry price). SFAS 157 emphasizes that assets should not be valued at cost (an entry price) unless they can be disposed of at cost.

The “market” referred to in this definition is “the market in which the reporting entity would transact for the asset or liability, that is, the principal or most advantageous market for the asset or liability.” Thus, the definition specifies an orderly transaction in the most advantageous market. Market participants are buyers and sellers in the principal (or the most advantageous) market for the asset or liability. These market participants are (1) unrelated, (2) knowledgeable about factors relevant to the asset or liability and the transaction, (3) able to transact (that is, have the legal and financial ability to do so), and (4) willing to transact (that is, motivated but not forced or otherwise compelled to transact). SFAS 157 clarifies that the term fair value is intended to mean a market-based measure, not an entity-specific measure.

The fair value premise for an asset is the asset’s highest and best use, from the perspective of market participants, that would maximize a company’s future cash flows. A company’s intended use of an asset is not necessarily indicative of the highest and best use of that asset as determined by a market participant; the fair value measure is not an entity-specific measure that reflects only the company’s expectations for the asset. SFAS 157 requires fair value measures consider the perspectives of market participants and the assumptions those participants would use to price an asset or a liability.

The market price on the valuation date is fair value if there is an active market for the subject asset or liability but not if the market is thin. The FASB identifies three levels in the hierarchy of measurements to quantify fair value, with the highest level available to be used:

• Level 1 (highest-priority) inputs are quoted prices in active markets for identical assets or liabilities.

• Level 2 inputs are those other than quoted prices included within Level 1 that are directly or indirectly observable.

• Level 3 inputs are unobservable inputs that reflect assumptions about what market participants would use in their pricing analyses.

This implies that, if there is an active market for the subject asset, the quoted price on the valuation date applies. For assets for which there is not an active market but for which there is an active market for close comparables, the prices for the comparables, with appropriate adjustments for differences, could be used as inputs. The standard clearly favors observable market data. For other subject assets (Level 3 assets), other valuation methods, including a discounted cash flow (DCF), could be used as inputs. The company may use its own assumptions, but Level 3 inputs must be adjusted if information is available that indicates that market participants would use different assumptions.

Although the FASB emphasizes “market participant assumptions at the measurement date,” there are differences between “fair value” for financial reporting purposes and “fair market value.” For example, SFAS 157 apparently makes a (perhaps unintended) distinction between legally imposed restrictions on sale (for example, restricted stock, which normally should be discounted) and market-imposed restrictions (for example, blocks of stock that are too large to be sold without depressing the market, which should not be discounted for what the market refers to as blockage). Blocks of stock are to be valued at the price multiplied by the quantity, with no discount applied for the size of the block. However, there is the contrary opinion that no discounts are applied for SFAS 123R.17 The FASB says that it did not adopt the definition of fair market value because it did not want the definition of fair value to be saddled with the nuances of court interpretations of fair market value.

The primary distinguishing characteristic of investment value is that it denotes value to a particular owner or investor. This is in contrast to fair market value, which is a concept of value in exchange, assuming hypothetical and typically motivated buyers and sellers. In other words, investment value is the value to a particular individual or entity, considering that individual’s or entity’s situation, perceptions, and motivation, but not necessarily value in the marketplace. This is also essentially the same way that investment value is defined in the context of real estate appraisal.18

Investment value is generally a “subjective” value, whereas fair market value is an “objective” value.

Valid reasons for the investment value to one particular owner or prospective owner to differ from the fair market value include the following unique factors:

1. Synergies with other operations owned or controlled—for example, a buyer has a particular use for the particular property

2. Relationships with other owners

3. Differences in estimates of future earning power and/or perception of degree of risk

4. Differences in aversion to or willingness to accept degrees of risk

5. Differences in income tax status

Whether or not the term investment value is actually used, the concept is found frequently in business valuations for marital dissolution. That is, the courts often focus on value to the spouse who operates the business as opposed to value that could be realized in the market.

Finally, investment value has a slightly different meaning in the context of dissenting stockholder suits. In this context, it means a value based on earning power. However, the appropriate present value discount rate or the direct capitalization rate is usually considered to be a consensus rate rather than a rate singularly appropriate for any specific investor.

Financial analysts that follow and report on publicly traded stock commonly use intrinsic value (sometimes called fundamental value) to report value. Intrinsic value differs from investment value in that it represents an analytical judgment of value based on the investment characteristics perceived by a financial analyst rather than on how the characteristics comport to the circumstances of a particular investor.

Concurrence on the meanings of intrinsic value and fundamental value is found in the following definitions from an authoritative reference in the accounting field:

Intrinsic value: The amount that an investor considers, on the basis of an evaluation of available facts, to be the “true” or “real” worth of an item, usually an equity security. The value that will become the market value when other investors reach the same conclusions. The various approaches to determining intrinsic value of the finance literature are based on expectations and discounted cash flows. See expected value; fundamental analysis; discounted cash flow method.19

Fundamental analysis: An approach in security analysis which assumes that a security has an “intrinsic value” that can be determined through a rigorous evaluation of relevant variables. Expected earnings is usually the most important variable in this analysis, but many other variables, such as dividends, capital structure, management quality, and so on, may also be studied. An analyst estimates the “intrinsic value” of a security on the basis of those fundamental variables and compares this value with the current market price of this security to arrive at an investment decision.20

In securities analysis, intrinsic value is generally considered the appropriate price for a stock according to the perspective of an analyst who has completed a fundamental analysis of the company’s assets, earning power, and other factors. Two University of Chicago professors comment on the notion of intrinsic value as follows:

The purpose of security analysis is to detect differences between the value of a security as determined by the market and a security’s “intrinsic value”—that is, the value that the security ought to have and will have when other investors have the same insight and knowledge as the analyst.21

Typically, if the market value is below what the analyst concludes is the intrinsic value, the analyst considers the stock a “buy.” If the market value is above the assumed intrinsic value, the analyst suggests selling the stock. It is important to note that such “buy” and “sell” assumptions are both predictive and predicated on the notion that at some point in the future the market can and will be made to realize the same level of knowledge and insight about the stock as the analyst.

It is important to note that the concept of intrinsic value cannot be entirely disassociated from the concept of fair market value. This is because the actions of buyers and sellers based on their specific perceptions of intrinsic value eventually lead to the general consensus market value in the course of the constant and dynamic changes in market value over time.

Case law often refers to intrinsic value. However, almost universally, such references do not define the term other than by reference to the language in the context in which it appears. Such references to intrinsic value can be found both in case opinions in which there is no statutory standard of value and also in case decisions in which the statutory standard of value is specified as fair value or even fair market value. When references to intrinsic value appear in the relevant case law, the court usually is referring to notions such as those discussed in this section. It is also common to find court cases that use the term intrinsic value to mean the inherent worth of the stock to the owner—in other words, to equate the term to investment value, as defined earlier.

Acquisition value means the value to a particular acquirer. It is very similar to strategic value (see below). In this sense, it falls within the concept of investment value, as described in the previous section. The term may also be used to denote the actual price at which a transaction occurred. In this sense, it would be the same as transaction value, described more fully below.

The term book value is an accounting term, not a financial term, and it is not necessarily, or even usually, indicative of any of the definitions of value discussed in the previous section. It is not related to any concept of economic value.

The term represents historical costs of assets owned by the entity, less any depreciation or amortization deducted in the accounting system used by that entity. The American Society of Appraisers defines book value as follows:

With respect to assets, the capitalized cost of an asset less accumulated depreciation, depletion, or amortization as it appears on the books of account of the enterprise. With respect to a business enterprise, the difference between total assets (net of depreciation, depletion, and amortization) and total liabilities of an enterprise as they appear on the balance sheet.22

Many of a company’s most valuable assets, especially if goodwill and other intangible assets are developed internally rather than purchased,23 may not appear on the balance sheet at all. Similarly, there may be liabilities, especially those of a contingent nature, that do not appear on the balance sheet.

The term going-concern value has two separate and distinct meanings, depending on the context in which it is used.

In one sense, it refers to the premise of the total value of the operations of the company on an ongoing basis.

The other concept of going-concern value is that of an intangible asset. In that context, it means the value of having a system of operating assets, systems, and personnel in place, with the ability to operate. It can be thought of as the difference between merely a set of physical assets and a “turnkey” operation ready to do business. For example, in a marital dissolution case, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, in addressing the value of a professional practice, distinguished between the personal goodwill of the professional (not part of the marital estate) and the value of having support staff, systems, and other operating systems in place (the “going-concern value,” to be valued and included as part of the marital estate).24 Other courts have differed on this question, and, as always, it is critical for the lawyer and appraiser to refer to the appropriate case law.

A term that causes much confusion is enterprise value. Sometimes it is used to mean the market value of the company’s entire capital structure (all equity and long-term debt). Other times it is used to describe market cap plus interest-bearing debt plus preferred stock minus total cash and cash equivalents. At other times, it refers to the total value of the company’s common stock on a control basis. When this term is encountered, one should carefully try to interpret its meaning from the context in which it is used.

Liquidation value means the net amount that can be realized (after liquidation expenses) in either an orderly or a forced sale of the business assets or some portion of them.

A strategic or synergistic value reflects added benefits to a particular acquirer because of synergies with the acquiree. That is, it is a price or potential price reflecting all or some portion of the value of synergistic benefits created through the combination of the respective entities for which a buyer might be willing to pay. Such benefits could include, for example, increasing market share, reducing costs by combining operations, particularly in the form of either staff reductions, sale of redundant assets or economies of scale, and/or raising prices by eliminating a competitor, to name a few.

Synergistic value generally reflects some added value above fair market value. Because it reflects the value of benefits available to a particular buyer, it is usually considered to fall within the concept of investment value, as discussed previously.

Transaction value is the price at which an actual transaction occurs, either in the form of an asset sale or a stock sale. The International Business Brokers Association’s Business Brokers Glossary defines the term as follows:

The total of all consideration passed at any time between the buyer and seller for an ownership interest in a business enterprise and may include, but is not limited to, all remuneration for tangible and intangible assets such as furniture, equipment, supplies, inventory, working capital, noncompetition agreements, employment, and/or consultation agreements, licenses, customer lists, franchise fees, assumed liabilities, stock options, stock or stock redemptions, real estate, leases, royalties, earn-outs, and future considerations.

Some definitions exclude the value of noncompetition agreements and/or employment agreements on the basis that payments for these intangibles often are contingent on future personal performance.

Transaction value specifically refers to price as opposed to value. It is empirical (historical) in nature; it is not a legal standard of value. Price is the face value (the amount shown on the transaction documents) at which a specific transaction occurred, without any adjustment to cash equivalent value to reflect special terms. The price may or may not represent an arm’s-length negotiation. It may be arrived at by negotiation, by contract, by court order, or by some other means. It may or may not comport to any of the definitions of value discussed in the previous section. The use of transaction prices in the market approach to appraisal is further discussed in Chapter 16.

The search for the appropriate definition of value usually proceeds in approximately the following hierarchy:

• Statutory law

• Legally binding rules and regulations

• Contractual definitions of value

• Non-legally binding administrative rules

• Precedential court decisions

• Direction from the court

• Direction from the lawyer

• Use of IRS authority in non-tax situations.

• Opinions of other lawyers and appraisers

Our experience has been that statutes have the advantage of having the greatest force of law and the disadvantage of being the least explicit of all sources in defining value.

The relevant statutes may be either federal or state. For example, federal statutes require that valuations for tax purposes will be at fair market value.25 Most state statutes governing dissenting stockholders require that valuations will be at fair value and most (if using the Revised Model Corporation Act or a close variation of it) add that the valuation date will be the day before the event to which the shareholder dissents, without considering the effect of that event. Most state statutes governing marital dissolution are silent about definitions of value other than some language about valuation dates.

Specifics of statutory law are discussed in considerable detail in the various chapters relating to the purposes of the valuation, such as gift and estate tax, shareholder disputes, marital dissolution, and so on. The purpose of this chapter is simply to make the point that statutory law usually is the first stop in the quest for the proper legal definition of value. Some examples of statutory law include the following.

Federal Statutes

• Internal Revenue Code (IRC), especially Section 2031 on estate taxes, Section 2512 for gift taxes, and Subsection 2701–04 on intra-family transfers

• Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA), 29 USC Section 1002 (26)

• U.S. Bankruptcy Code, 11 USC Section 522(a)(2) (“value” means fair market value as of the date of filing the petition, or with respect to property that becomes property of the estate as of a certain date.)26

• Securities and Exchange Act

State Statutes

• State revenue codes

• State securities codes

• Business Corporations Act (often the Uniform Business Corporation Act), usually addressing dissenting stockholder valuations

• Statutes granting oppressed minority shareholder relief, including an appraisal option (in a growing number of states)

• Marital dissolution statutes, which generally do not address valuation matters

Many legislative bills authorize rules and regulations that have the force of law, with implementation delegated to an administrative authority. Examples include the following:

• Treasury regulations

• Federal Rules of Evidence and Civil Procedure

• Various state revenue regulations

• Department of Labor (DOL) proposed regulation 29 CFR Part 2510,27 Definition of Adequate Consideration for Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP) Stock

DOL issued the proposed regulation in 1988, it has never been finalized.

DOL issued the proposed regulation in 1988, it has never been finalized.

Despite lack of finalization, it provides guidance, and most ESOP appraisers consider compliance with it important.

Despite lack of finalization, it provides guidance, and most ESOP appraisers consider compliance with it important.

Parties sometimes are bound by contractual definitions of value in documents governing certain types of transactions. Such documents may include the following:

• Articles of organization

• Articles of incorporation or partnership

• Bylaws

• Shareholder or partnership agreements

• Prenuptial agreements

• Agreements entered into specifically for the purpose of settlement of the instant dispute, such as arbitration agreements

Such agreements may be very helpful in defining value for the purpose at hand, or they may be the source of another element of controversy:

• Is the definition of value legally binding in the instant case? Even if it is not, it may be accorded some weight, especially if it has been used in other transactions with some similar characteristics.

• Is the definition of value clear and unambiguous? Unfortunately, documents intended to provide guidance all too often are drafted with ambiguous language that leaves the interpretation open to controversy. We recommend that an appraiser be consulted to review draft language relating to value to be sure that the lawyers and all parties to the agreement understand the value implications in the document.

Many government agencies issue rulings containing their interpretations of definitions of value. Courts usually give consideration to such rulings, but a court will not necessarily accept them if it feels that they are not consistent with the law.

For example, the IRS issued Revenue Ruling 81-253, which states that a minority discount should not be applied to gifts of minority shares of stock if other members of the family control the company. IRS Revenue Rulings represent the position of the IRS, but they are not the law. The position taken in Revenue Ruling 81-253 lost every time it was challenged in court,28 and finally (after 12 years) the IRS reversed its position with Revenue Ruling 93-12, recognizing that shares were to be valued on the basis of the size of the block transferred, irrespective of attribution of family control value.

By far the richest source of specific guidance as to definitions of value in almost any legal context is interpretation found in precedential case decisions. This book contains many annotations to decisions on valuation issues in many legal contexts (for example, tax, dissent, and divorce) and in various jurisdictions. Careful study of precedential case law is a very important step in understanding the relevant legal definition of value.

Nevertheless, it is also important to examine the many challenges and pitfalls inherent in using precedential case law as a source of guidance for definitions of value.

• Lack of precedent. There are valuation issues for which no precedent exists in many state jurisdictions. Courts tend to then cite precedent from other states that have similar statutes governing the issue. Each lawyer, of course, seeks out precedents in other jurisdictions that support his or her position.

• Ambiguous language. Most judges are not experts in financial language, and financial language itself has many ambiguities. For example, an opinion may use the term fair market value and then accept valuation methods that reflect factors that are not consistent with most courts’ and financial analysts’ understandings of the definition.

• Distinguishable facts and circumstances. Lawyers and appraisers may sometimes identify facts and circumstances in the case that may lead to an interpretation of the definition of value different from that found in a seemingly on-point precedential decision.

• Sweeping generalizations. Opinions sometimes contain broad statements that, if read literally, would apply to a broader set of cases or circumstances than the court may have intended. It usually is preferable that the lawyer, rather than the appraiser, originate the discussion of such distinctions in court.

• Changing and contradictory precedents. Precedential positions on issues sometimes change as a result of revisiting an issue. Be sure to rely on the latest case decisions. Precedents within a jurisdiction sometimes seem to contradict each other. In such a case, one might look for possible differentiation in facts and circumstances to distinguish them. When relying on a U.S. Court of Appeals decision, remember that it is controlling only in the circuit that issued the opinion, and it is not uncommon to find different circuits holding contradictory opinions.

Sometimes, it is possible for the lawyer to request and get a ruling from the court on the definition of value and/or the applicable valuation date before the appraiser prepares the report. This can save a great deal of expense in preparing reports under different definitions of value.

Sometimes the lawyer has a clear-cut concept of the legal theory of the case, and that theory dictates a definition of value that the lawyer directs the appraiser to use. If the source of the definition of value is the lawyer rather than some quotable statutory or regulatory language, the appraiser is still responsible for its use, and must be in agreement to adopt it.

It is not uncommon for appraisers to cite IRS authority, such as Revenue Rulings, when describing the nuances of the definition of fair market value. If this is done for a valuation other than for federal taxes, it is important that the IRS standard be appropriate for the valuation.

From time to time one may gain points of view on definitions of value from experienced lawyers or appraisers. These may come from either writings or discussions.

For example, one leading California corporate lawyer has published clear-cut ideas about the definition of fair value under California Corporations Code 2000. This attorney adds that “the cases provide only a patchwork of insights, only some of which are consistent with the basic purpose of Section 2000.”29

“Levels of value” deal with both control and marketability, which may have a significant effect on the value of any business entity.

By levels of value, we mean the varying degrees of control it is possible for an investor to hold in relationship to a particular business entity. The degrees of responsibility and freedom in such relationships are integral to determining specific value.

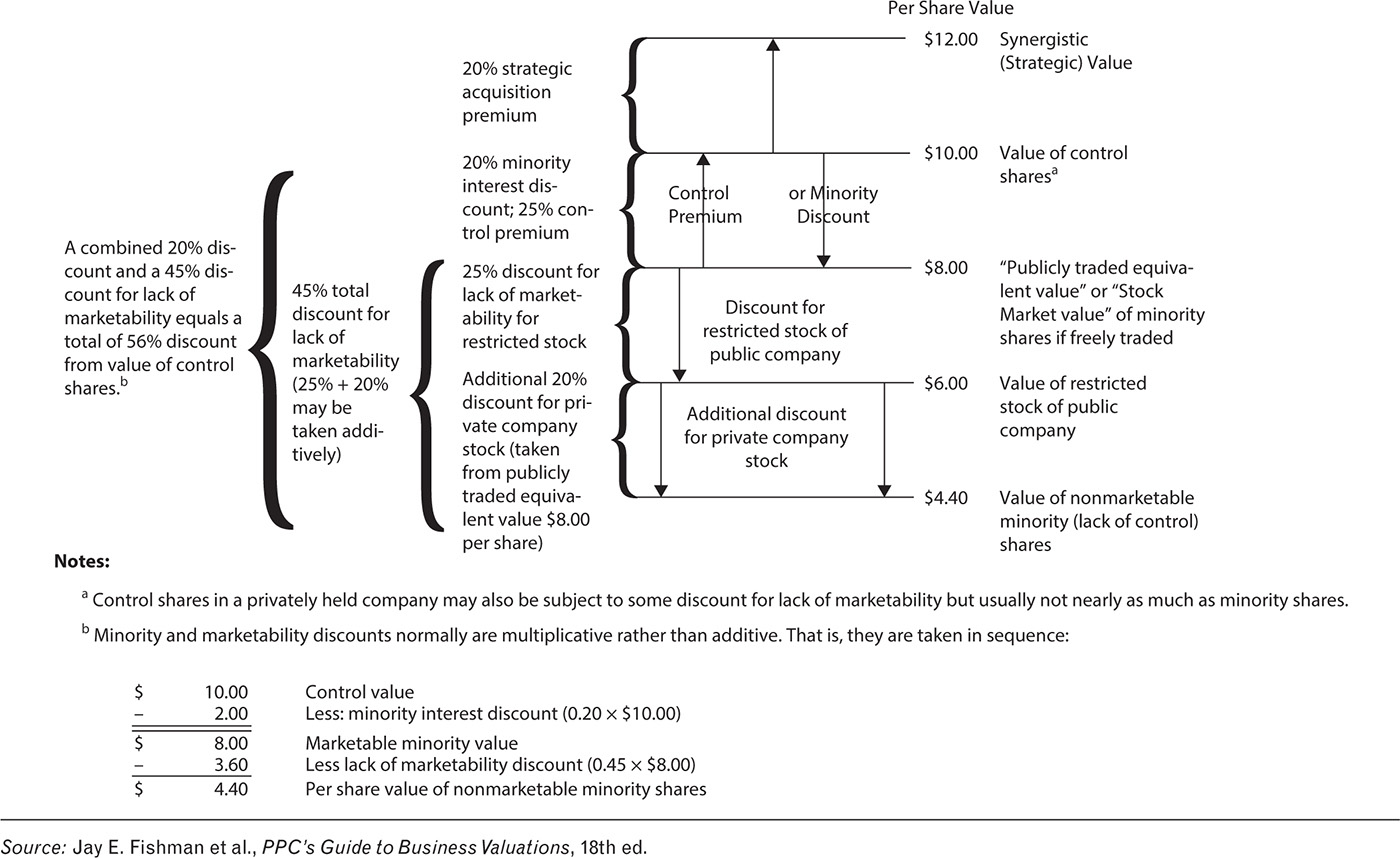

The attorney and the appraiser should decide at the outset what level of value the appraisal will represent. Exhibit 13.1 is a schematic depiction of the basic levels of value. The relative dollar amounts and percentages used are strictly for example purposes. Each situation is analyzed on a fact-specific basis.

Levels of Value in Terms of the Characteristics of Ownershp

The typical levels of value to be appraised in a closely held company are either control or minority nonmarketable. “Nonmarketable” means that the shares cannot be sold to the general public because they have not been registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

The level above control is “strategic acquisition value,” which is the price that a company that has a specific reason for wanting to purchase a company might pay, often because the purchase will create a synergy with its existing businesses. This level could be appropriate if the purpose of the appraisal was to estimate a price that a synergistic buyer might pay. However, unless there is a group of synergistic buyers that creates a market, fair market value reflects the value of the company on a stand-alone basis and does not include possible synergies with other companies.

The line below control, “minority marketable,” reflects an estimate of what the minority shares might trade for in a public market. When valuing minority shares in a private company, it may not even be necessary to estimate what the company as a whole would be worth—one might simply find guideline companies in the public market, estimate the value if publicly traded, and deduct a discount for lack of marketability from that. However, there is a school of thought that, although publically traded stocks are clearly minority interests, their prices are tantamount to prices of controlling interests.

The next level down is “restricted stocks of public companies.” Some publicly traded companies may not have all their shares registered for public trading (they might issue unregistered shares for an acquisition, for example), but they can sell blocks of unregistered shares to qualified investors. These blocks are usually sold at a discount compared to the same day’s public trading price.

Until the 1990s, these discounts averaged about 35 percent, and the restricted stock discounts were sometimes used as a proxy for the discount for lack of marketability for closely held stocks. Around 1990, the SEC started to loosen restrictions on sales of restricted stocks, and, accordingly, the discounts started to come down. But the loosening of SEC regulations for restricted stocks of publicly traded companies did nothing to enhance the marketability of closely held stock, for which there is little or no market. So the lower line reflects the fact that closely held stocks are much less marketable than restricted stocks of public companies.

These varying levels of value can have a significant impact on the eventual value because they will determine the extent of the discounts for lack of marketability or control, if any.

By a premise of value, we mean an assumption as to the status of the business under which a transaction would be expected to take place. That is, would it be as a going concern or in liquidation, or some variation or combination of going concern or liquidation value? The selection among alternative possible premises of value obviously can have a major impact on value.

In some situations, the premise (or premises) of value is mandated as part of the definition of value by controlling documents or the purpose of the valuation. In other situations, the premise of value is left to appraiser judgment. For example, it may be left to the appraiser to determine what premise of value represents the highest and best use of the business or property.

Virtually all businesses or interests in businesses may be appraised under any of the following four alternative premises of value:

1. Value as a going concern. Value in continued use, as a mass assemblage of income-producing assets, and as a going-concern business enterprise.

2. Value as an assemblage of assets. Value in place, as part of a mass assemblage of assets, but not in current use in the production of income, and not as a going-concern business enterprise.

3. Value as an orderly disposition. Value in exchange, on a piecemeal basis (not part of a mass assemblage of assets), as part of an orderly disposition; this premise contemplates that all the assets of the business enterprise will be sold individually and that they will have normal exposure to their appropriate secondary market.

4. Value as a forced liquidation. Value in exchange, on a piecemeal basis (not part of a mass assemblage of assets), as part of a forced liquidation; this premise contemplates that the assets of the business enterprise will be sold individually and that they will have less than normal exposure to their appropriate secondary market.30

Each of these alternative premises of value may apply under the same standard, or definition, of value. For example, the fair market value standard calls for a “willing buyer” and a “willing seller.” Yet the willing buyer and seller have to make an informed economic decision as to how they will transact with each other with regard to the subject business. In other words, is the subject business worth more to the buyer and the seller as a going concern that will continue to operate as such, or as a collection of individual assets to be put to separate uses? In either case, the buyer and seller are still “willing.” And in both cases, they have concluded a set of transactional circumstances that will maximize the value of the collective assets of the subject business enterprise.31

If left to the judgment of the appraiser, the premise of value selected may depend on whether the interest is being valued on a controlling interest or minority interest basis. In a controlling interest valuation, the selection of the appropriate premise of value typically is a function of the highest and best use of the collective assets of the subject business enterprise. The appraiser might value the operations of the business on a going-concern basis and the assets not necessary to operations on a liquidation basis.

If valuing on a minority interest basis, the appraiser is more likely to value on the assumption of “business as usual”—that is, as a going concern. In other words, the appraiser normally would not assume a liquidation of any assets unless there was an indication that such a liquidation was imminent. This treatment has been met with acceptance by courts.32