In the ideal single-family residential appraisal, if the appraisal had three comparable properties, one would be slightly higher, one slightly lower, and one exactly the indicated value for the subject property. In reality, a range of comparable sales like this is rarely found, so the appraiser must do the best job with the sales that are available.

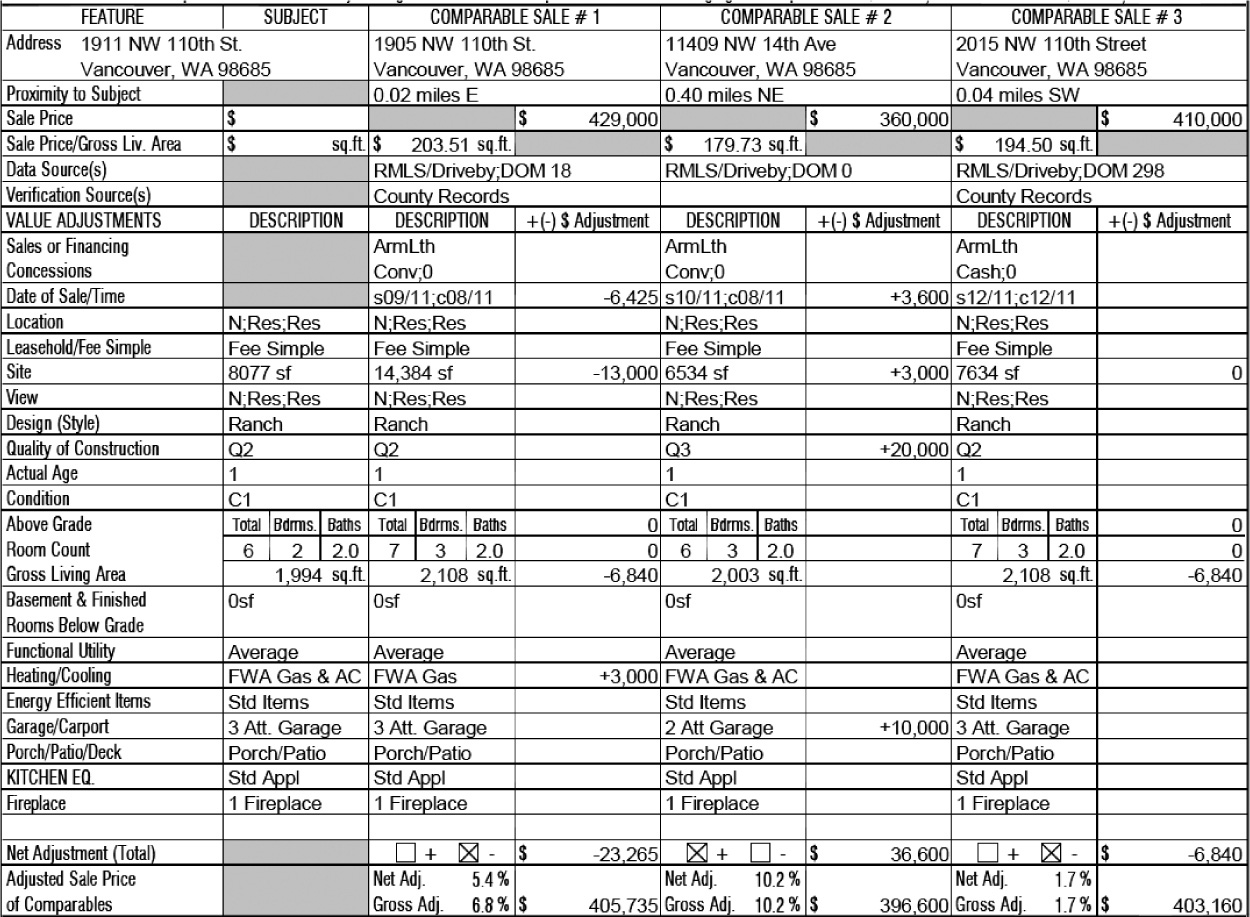

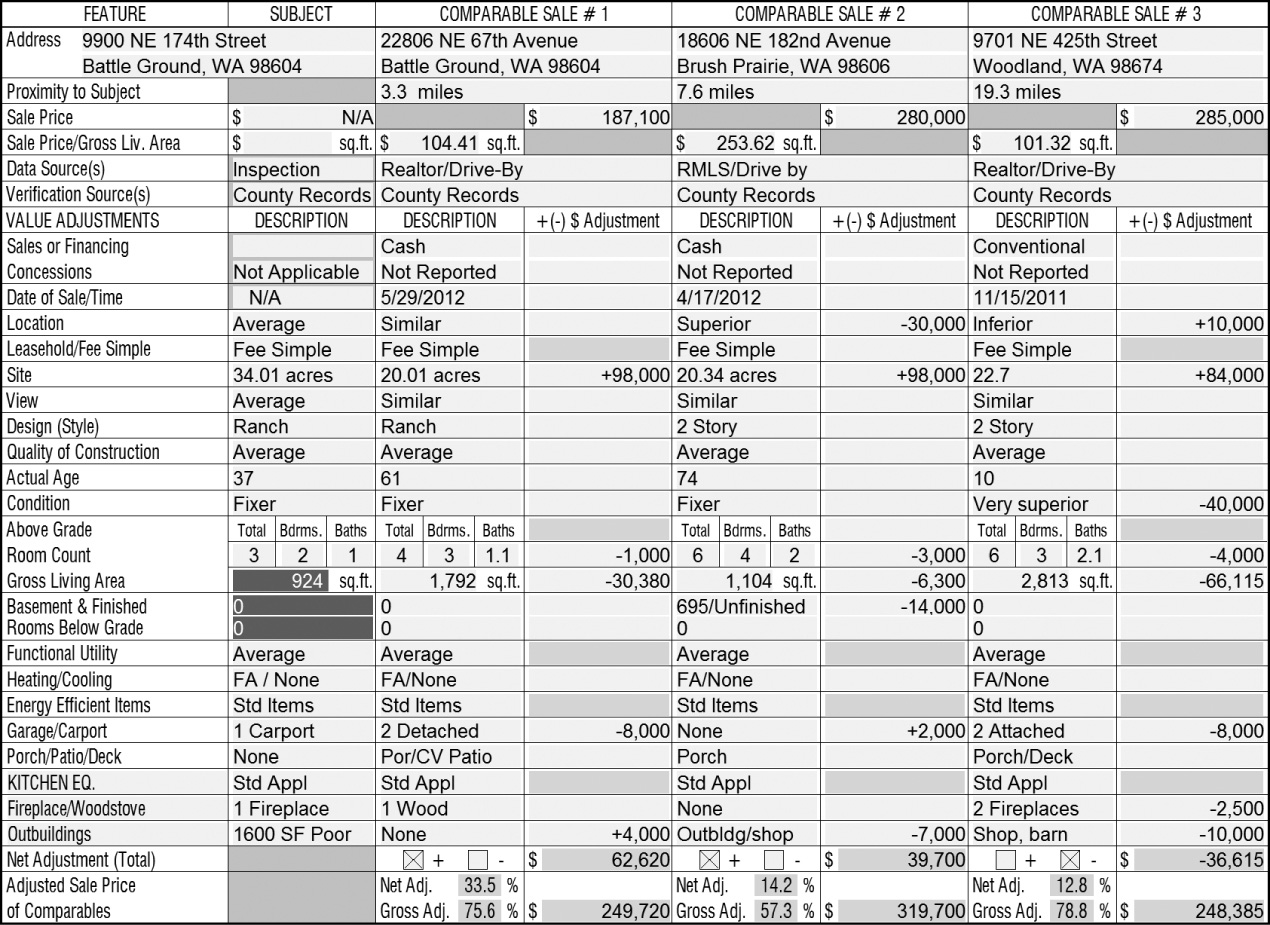

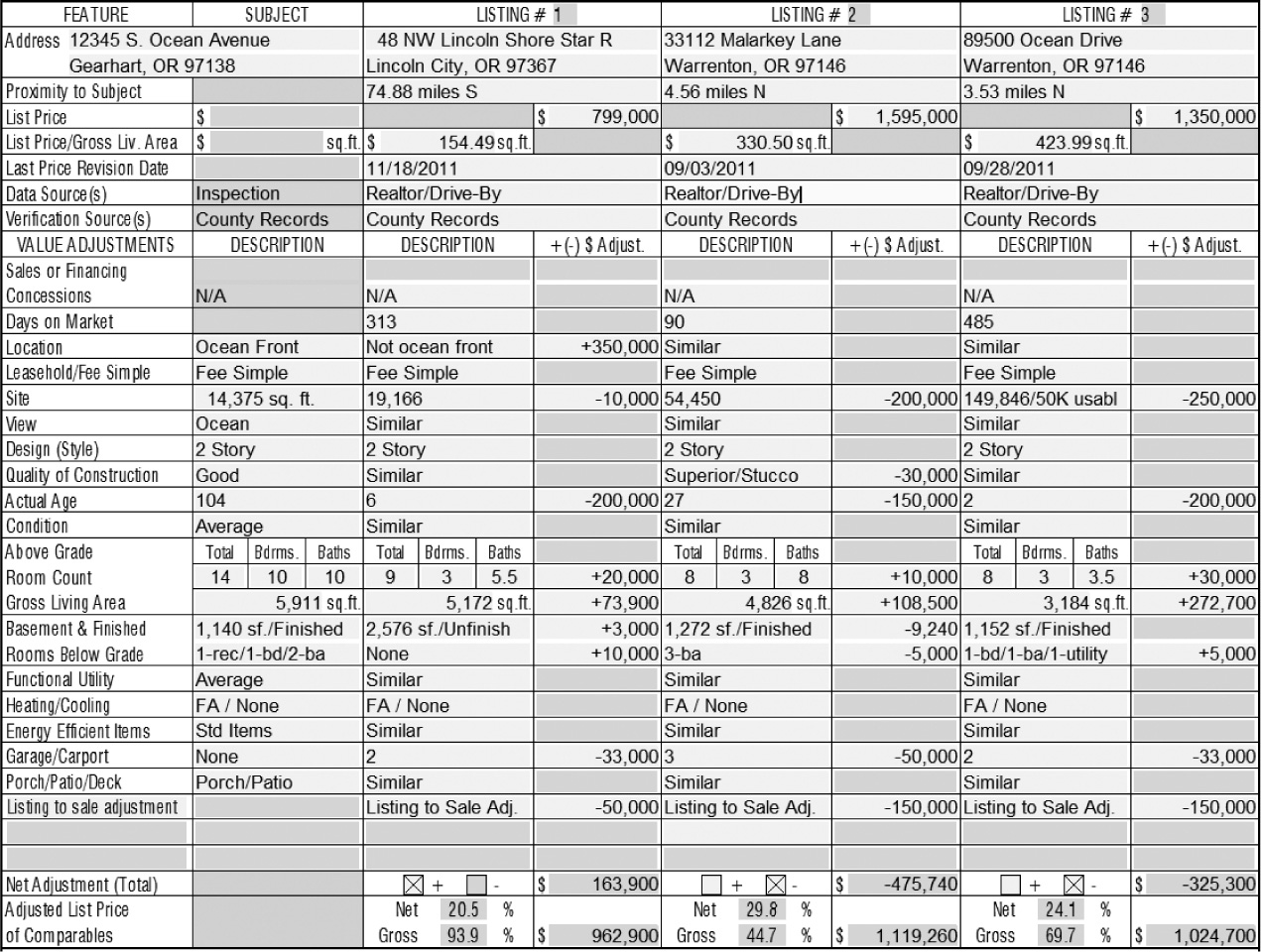

Exhibit 2.1 is the sales comparison approach sheet for a typical single-family residential appraisal, which is on what is called a Fannie Mae Form 1004. Most residential appraisals use this form because it is the one needed to sell loans to the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) and Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac), which purchase most of the residential mortgages in the United States. The form uses codes for certain entries such as quality of construction and condition. The codes are part of a program called the Uniform Mortgage Data Program, which standardizes entries so that appraisers will use the same reference for various descriptions of the characteristics of houses.

Sales Comparison Sheet for a Typical Single-Family Residential Appraisal (Fannie Mae Form 1004)

For many years, instead of a code, the appraiser would enter a word. For instance, under “condition,” the appraiser might enter “average” for the subject and “inferior” for one of the comparable sales. Since individual appraisers used different words and methods, a standardized system of codes (Exhibits 2.2 and 2.3) was introduced, as is seen in Exhibit 2.1. However, because these codes must be looked up to understand them, for the rest of this book the older system that used words rather than codes will be used to save the reader the trouble of looking up the codes.

Quality of Construction Ratings and Definitions

Q1

Dwellings with this quality rating are usually unique structures that are individually designed by an architect for a specified user. Such residences typically are constructed from detailed architectural plans and specifications, and they feature and an exceptionally high level of workmanship and exceptionally high-grade materials throughout the interior and exterior of the structure. The design features exceptionally high-quality exterior refinements and ornamentation and exceptionally high-quality interior refinements. The workmanship, materials, and finishes throughout the dwelling are of exceptionally high quality.

Q2

Dwellings with this quality rating are often custom designed for construction on an individual property owner’s site. However, dwellings in this quality grade are also found in high-quality tract developments featuring residences constructed from individual plans or from highly modified or upgraded plans. The design features detailed, high-quality exterior ornamentation and high-quality interior refinements and detail. The workmanship, materials, and finishes throughout the dwelling are generally of high or very high quality.

Q3

Dwellings with this quality rating are residences of higher quality built from individual or readily available designer plans in above-standard residential tract developments or on an individual property owner’s site. The design includes significant exterior ornamentation and interiors that are well finished. The workmanship exceeds acceptable standards, and many materials and finishes throughout the dwelling have been upgraded from “stock” standards.

Q4

Dwellings with this quality rating meet or exceed the requirements of applicable building codes. Standard or modified standard building plans are utilized, and the design includes adequate fenestration and some exterior ornamentation and interior refinements. Materials, workmanship, finishes, and equipment are of stock or builder grade and may feature some upgrades.

Q5

Dwellings with this quality rating feature economy of construction and basic functionality as main considerations. Such dwellings feature a plain design using readily available or basic floor plans featuring minimal fenestration and basic finishes with minimal exterior ornamentation and limited interior detail. These dwellings meet minimum building codes and are constructed with inexpensive, stock materials with limited refinements and upgrades.

Q6

Dwellings with this quality rating are of basic quality and lower cost; some may not be suitable for year-round occupancy. Such dwellings are often built with simple plans or without plans, often utilizing the lowest-quality building materials. Such dwellings are often built or expanded by people who are professionally unskilled or possess only minimal construction skills. Electrical, plumbing, and other mechanical systems and equipment may be minimal or nonexistent. Older dwellings may feature one or more substandard or nonconforming additions to the original structure.

Source: Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) Uniform Data Appraisal Specification.

Condition Ratings and Definitions

C1

The improvements have been recently constructed and have not been previously occupied. The entire structure and all components are new, and the dwelling features no physical depreciation.

Note: Newly constructed improvements that feature recycled or previously used materials and/or components can be considered a new dwelling provided that the dwelling is placed on a 100 percent new foundation and the recycled materials and the recycled components have been rehabilitated and/or remanufactured into like-new condition. Improvements that have not been previously occupied are not considered new if they have any significant physical depreciation (that is, newly constructed dwellings that have been vacant for an extended period of time without adequate maintenance or upkeep).

C2

The improvements feature no deferred maintenance, there is little or no physical depreciation, and they require no repairs. Virtually all building components are new or have been recently repaired, refinished, or rehabilitated. All outdated components and finishes have been updated and/or replaced with components that meet current standards. Dwellings in this category are either almost new or have been recently completely renovated and are similar in condition to new construction.

Note: The improvements represent a relatively new property that is well maintained with no deferred maintenance and little or no physical depreciation, or they may represent an older property that has been recently completely renovated.

C3

The improvements are well maintained and feature limited physical depreciation due to normal wear and tear. Some components, but not every major building component, may be updated or recently rehabilitated. The structure has been well maintained.

Note: The improvement is in its first cycle of replacing short-lived building components (appliances, floor coverings, HVAC, and so on) and is being well maintained. Its estimated effective age is less than its actual age. It also may reflect a property in which the majority of short-lived building components have been replaced but not to the level of a complete renovation.

C4

The improvements feature some minor deferred maintenance and physical deterioration due to normal wear and tear. The dwelling has been adequately maintained and requires only minimal repairs to building components and/or mechanical systems and cosmetic repairs. All major building components have been adequately maintained and are functionally adequate.

Note: The estimated effective age may be close to or equal to its actual age. It reflects a property in which some of the short-lived building components have been replaced, and some short-lived building components are at or near the end of their physical life expectancy; however, they still function adequately. Most minor repairs have been addressed on an ongoing basis resulting in an adequately maintained property.

C5

The improvements feature obvious deferred maintenance and are in need of some significant repairs. Some building components need repairs, rehabilitation, or updating. The functional utility and overall livability are somewhat diminished due to condition, but the dwelling remains usable and functional as a residence.

Note: Some significant repairs are needed to the improvements due to the lack of adequate maintenance. It reflects a property in which many of its short-lived building components are at the end of or have exceeded their physical life expectancy but remain functional.

C6

The improvements have substantial damage or deferred maintenance with deficiencies or defects that are severe enough to affect the safety, soundness, or structural integrity of the improvements. The improvements are in need of substantial repairs and rehabilitation, including many or most major components.

Note: Substantial repairs are needed to the improvements due to the lack of adequate maintenance or property damage. It reflects a property with conditions severe enough to affect the safety, soundness, or structural integrity of the improvements.

Source: Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) Uniform Data Appraisal Specification.

Exhibit 2.2 shows the quality (Q) of construction ratings and definitions. Exhibit 2.3 shows the condition (C) ratings and definitions. Exhibit 2.4 shows the standardized abbreviations. These exhibits come from the Uniform Appraisal Data Specification, which is a product of the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) that regulates Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The full manual can be found on the Fannie Mae website: https://www.fanniemae.com/singlefamily/uniform-appraisal-dataset.

Standardized Abbreviations

The following are comments on each entry on the sales comparison approach portion of the form, in order of how they appear starting at the top of the page. Beside information for each category, red flags are noted where errors or inaccurate information might be an issue.

As is taught in real estate brokerage, the location is perhaps the most important characteristic for comparable properties. The sales should be in the same area as the subject property or at least in an area equal in quality to the subject. For most residential appraisals located in urban or suburban areas, lenders prefer to see sales that are within a mile of the subject property. With rural properties, which are often on large acreages, distances may be much greater. Moreover, rural properties tend to have more diverse characteristics, meaning that more adjustments are often necessary. In other words, some subdivisions have “cookie-cutter,” or at least somewhat similar, houses, as compared to large-acreage properties that are rarely similar. Larger luxury homes also often require more adjustments.

The type of financing may make some difference that requires an adjustment, but it will probably be minor. There should be no adjustments between Veterans Administration (VA), Federal Housing Administration (FHA), and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and conventional financing. However, there might be a warranted adjustment for owner financing depending on how different the terms were from these other financing instruments. If a sale was made for 2 percent interest amortized for 40 years and the typical financing was 6 percent interest with a 30-year amortization, then an adjustment would be needed. Essentially, the value of the under-market financing would need to be calculated to determine the savings compared to typical financing to deduce the amount of the adjustment.

More commonly, a sale will have a sales concession, which should be adjusted for in the sale price, because the effect of a concession is to reduce the sale price of the property. In other words, concessions make the sale price artificial compared to sales without concessions because the seller is giving up something of value to sell the property, even though the price may remain the same. Concessions are often made with the intention of getting more financing than would normally be allowed. For instance, if a lender were requiring a 10 percent down payment on a $200,000 house, the buyer would need to have $20,000 for the transaction. However, if the buyer and seller agreed to a sale price of $210,000 with the borrower getting a $10,000 sales concession in escrow, then the down payment would be $21,000, but the buyer would need only $11,000 for the down payment. In reality, it would be the lender who would carry more risk because instead of financing 90 percent of the value of the home, the lender would now be financing $189,000, or 94.5 percent of the actual home value.

Therefore, if the subject property has concessions or the comparable sales have them, the concessions should be subtracted from the sale price to get the actual sale price. Some appraisers may state that the concessions are customary for the area, but that is irrelevant. An adjustment should be made for any concessions because they effectively reduce the sale price.

The date of the sale becomes exceedingly important in a fluctuating economy where property values are changing. With residential real estate the typical requirement and/or preference is that the sales have sold within six months. However, when the market is changing quickly, a six-month-old sale may be obsolete and unrepresentative of the current value of the subject property, and sales less than three months old may be more appropriate. In any event, the comparable sales used in appraisals need to be considered in light of the current economic situation, particularly when recent changes have occurred in the economy.

It is also important in a fluctuating market for the appraiser to examine listings and include them as well as comparable sales because they will give an understanding of the current market asking prices for similar properties. Listings are only valuable in showing the high end of the market, and sometimes there are no reasonably priced listings that exist. If the appraiser does not show listings, then the reviewer, in analyzing the appraisal, might look at properties for sale on websites such as www.realtor.com to see listings that might help in the analysis of the appraisal.

Adjustments are normally made for sites that differ from the subject property by over 1,000 square feet, although that is not the case for some locations. If the subject has a particularly small lot for the region it is in, such as 2,500 square feet where most homes have a minimum of 5,000 square feet, a more sizable adjustment is normally required than if the subject had 5,000 square feet and the comparable sale had 7,500 square feet. The differential of 2,500 feet is not as significant for the larger parcels because for the area they are still within the norm, whereas an unusually small lot may have a major effect on the market value.

Consequently, in valuing the home with a 2,500-square-foot lot, it would be important for the appraisal to have at least one and preferably two comparable sales with the same size lot to alleviate any concern that there is a detrimental effect due to the size differential.

The view is often not a major adjustment, if it is a matter of a certain type of street view compared to another. However, an ocean view, in some areas, and a city light view for a high-rise condominium are exceptions, and they can make a huge difference in the price of a property.

There may be an adjustment in this category if it is warranted, but often there is no measurable difference in design styles. However, a basic example might be that an adjustment might be required between a ranch style and a two-story home, if the market data shows that there is a continuous pattern of buyers paying more for ranch-style homes. This decision can be very subjective, so the reviewer might want to examine it carefully if the appraiser has made a substantial adjustment, particularly if there are no comments explaining why the adjustment was made in the summary of sales comparison approach below the adjustment grid.

The differences in the quality of the construction should be explained if they are not obvious. Photographs of the subject home and the comparable sales might be important to look at in determining if the appraisal is accurate. Adjustments here might be for something as small as the difference between metal windows and updated vinyl windows, or they may be as significant as the difference between a luxury custom home and a tract home with basic construction and amenities.

Since the form asks for the actual age, that should be entered here. However, often appraisers will also enter what is called the economic age. By entering a number for the economic age, the appraiser is denoting that, for instance, a home that was built 60 years ago is only 30 years old economically. The typical reason would be that it has been updated and maintained to approximate a younger age than the original construction date. If this information is entered, it should have the original age (O) and then the economic age (E), which might be entered as O – 60, E – 30 or in some similar format.

One of the largest areas of inaccuracy is in comparing the condition of the comparable sales to the subject. Looking at photographs in the appraisal can help, but the appraiser should also comment on the differences if there is an adjustment. The appraiser often depends on the listing information from the sale of a comparable property, and that information may not be accurate.

Normally bedroom differences do not require an adjustment, but the exception might be if a home had only one bedroom and it was compared to homes with more than one bedroom. The reason is that a one-bedroom home is unique, and it is often considered deficient, and therefore worth significantly less since most home buyers want at least two bedrooms. There should always be adjustments for the number of bathrooms if the comparables differ from the subject property. However, the adjustment between a one-bathroom home and a two-bathroom home might be larger than an adjustment between a home with two bathrooms and one with three because a home with only one bathroom might be a lot less marketable than a home with two.

With larger homes with many bathrooms, the law of diminishing returns is applicable. Adjustments for bathrooms may decrease with large homes that have more than three bathrooms. For instance, the difference between a home with two bathrooms and three bathrooms might require a larger adjustment than the difference between a five-bathroom home and six-bathroom home.

Often the location and size of a home are the most important characteristics affecting the price. Appraisers measure homes from the outside of the home with the exception of attached properties such as condominiums, which are measured based on the inside dimensions. The appraiser generally uses the square footage for the comparable sales that is reported in the multiple listing service or other data service and does not personally measure them.

The appraiser is supposed to adjust for square footage differences based on market evidence. This means that the appraiser should look at the sales of homes that are similar to the subject but vary in size to determine the square foot value differential. The price per square foot that is computed is noted at the top of the form and labeled “Sale Price/Gross Liv. Area” will normally not be the same number as the adjustment for the price per square foot. The “Sale Price/Gross Liv. Area” is the price of the home divided by the size, which includes the land, but the adjustment for size is based on what the appraiser thinks the market recognizes for the differential, and it does not have a linear relationship with the sale price divided by the gross living area. They are two different numbers and should not be confused.

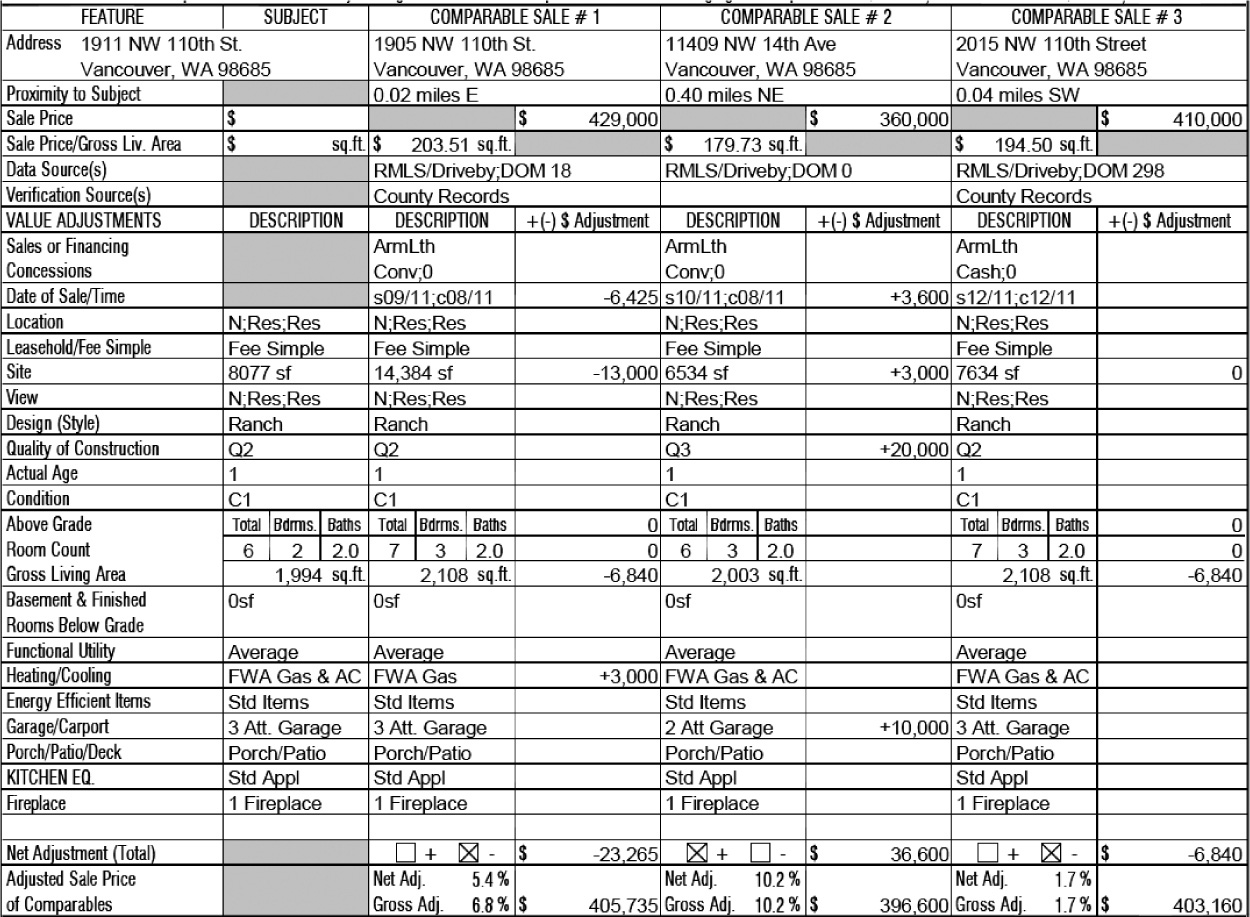

Exhibit 2.6 is an example of an appraisal that has been inflated by using sales that are larger than the subject property. In this example, the subject property is 2,809 square feet, and the comparable sales are 3,622, 3,822, and 3,450. The adjustment for the square footage is $40 per square foot for the size, which is questionable for homes of this size because they are generally more expensive and luxurious than homes the size of the subject, making them more expensive to construct. Since there are no smaller properties, there is no way to know the value of the subject from these comparable sales.

Residential Appraisal Inflated by Using Sales That Are Larger Than the Subject Property

The adjustment for the bathrooms may also be low since larger homes often have luxury bathrooms that can be quite expensive. The example here is a very obvious one. However, an appraiser might have also searched for a very high sale that was close to the size of the subject and then used it as well as two of the larger sales, which would make the appraisal more acceptable but might still inflate it if the appraiser was trying to reach a certain value. In such a situation a reviewer might ask the appraiser why only larger homes were used and what evidence the appraiser used to determine the $40 per square foot adjustment amount.

Nevertheless, the appraiser does not make the comparable sales, and there are instances where finding more comparable sales is not possible because they don’t exist. The appraiser may have had no motive in using larger properties, but the result is the same—the value has not been adequately proven. In such a case, the appraiser may be asked to expand the search for sales to include similar neighborhoods that are farther away, use sales that are older and adjust them for age, or use sales that are smaller to counter the larger sales.

This category is for basements, and the amount of adjustment can vary greatly due to the finish of the basement (finished, unfinished, partially finished) and the type of basement. Types range from daylight basements that are finished as well as the rest of the house is finished to basements that have no windows and are completely unfinished. Adjustments should be made accordingly. Values might be inflated if too much credit is given for a basement that has little value due to its level of finish.

This category rarely has adjustments because most homes do not have significant functional problems. A simple example of a home that might need an adjustment would be one in which a bedroom could be accessed only by walking through another bedroom.

Adjustments in this category vary with the type of heating and cooling systems a home has, and the adjustments will be greater in certain parts of the country depending on the variance of the weather. For instance, in a very warm climate in the South, the adjustment for the lack of air-conditioning might be substantial, but for a property in the Northwest, it might be much less.

This could include solar panels and other efficiency amenities.

Adjustments for this category vary. In some larger houses, less than a three-car garage can be a deficiency that reduces the salability of the home if the smaller garage is not typical. After three or four garages, the adjustment will diminish per additional garage space.

Often the adjustment for these items is small, and it varies according to size and quality.

Adjustments for kitchen equipment would be for only built-in appliances. Appliances that can be moved are considered personal property, and they are normally not part of the house appraisal. The value of such equipment depreciates very quickly, and if an adjustment were warranted, it would likely be very small.

Generally adjustments for these features are relatively small.

Small sheds are often movable and require no adjustment. Larger outbuildings are typically on properties that are on acreage, but they rarely add the value of what they cost to construct, so the adjustment for these might appear small.

These boxes show the percentages of the net and gross adjustments. The net adjustment refers to the final total amount of the adjustments, which is the addition of all the adjustments negative and positive. For instance, if an adjustment for inferior condition was made for +$10,000 and an adjustment was made for the same property for superior location for −$12,000, the net adjustment would be the difference, or $2,000.

The gross adjustment is the total of all the adjustments without consideration of whether they are positive or negative amounts. Therefore the gross adjustment for this example would be $22,000. Most lender guidelines want the gross adjustment to be no more than 25 percent, and the net adjustment to be no more than 15 percent of the sale price. Additionally, some want no adjustment to a single item to be more than 10 percent of the sale price.

These requirements are generally realistic for tract homes, but for homes with acreage and high-end homes, they often cannot be met. The reason is that as homes become more expensive, they become more dissimilar and require more adjustments. Acreage properties also often have various characteristics, such as different sizes of acreage, barns, shops, and other amenities for which it is difficult to find similar comparable sales.

Another situation that tends to skew the percentage of adjustment is when the subject or some of the comparable sales have basements and others do not. Since the basement adjustment is considered separate from the main square footage, a large adjustment must be made, which increases the net and gross adjustment totals. For instance, if the subject has 1,000 square feet at street level and 1,000 square feet of daylight basement, and a comparable sale has 2,000 square feet all at street level, a large adjustment must be made to the comparable sale since street-level and basement square footage must be entered separately. The adjustments will total a high percentage, but in reality the homes are the same size, except that they are configured differently and the daylight basement footage will probably be worth less than the street-level footage.

There are different levels of appraiser licenses, and not all residential appraisers can value high-end properties over a certain amount of value. Multi-million-dollar homes often become complex appraisals because of the dearth of similar comparable sales and the difficulty in making accurate adjustments for the variance of amenities between the subject and the comparable sales. For this reason, lenders often want more than one appraisal for high-value homes. Many appraisers can value typical low-end tract homes, but it requires an experienced, advanced appraiser to value high-value homes.

The following are some guidelines to keep in mind in analyzing the comparable sales comparison approach.

In the sales comparison approach, adjustments are always made to the comparable sales and never to the subject. If the comparable sale is inferior to the subject, it requires an upward adjustment or a plus to the starting point, which is the sale price. If the sale is superior, the adjustment is downward and is subtracted from the sale price. Even experienced appraisers sometimes make mistakes and add instead of subtracting an adjustment or vice versa.

In some locations, some amenities do not require the same amount of adjustments as others—the adjustments are market driven, and the market is local. For instance, in the Northwest, a large, $60,000 exterior in-ground swimming pool may get only a $10,000 adjustment because the weather does not permit much usage, and there is little demand for pools. Conversely, in a warm state like Florida, the lack of a swimming pool in an upper-end neighborhood where most houses have them may require a large adjustment because the marketability of the house may be severely affected.

Some amenities may be considered a superadequacy, which will be discussed in more detail in the industrial section of this book. A superadequacy may be defined as an excessive amenity that is not typically found in properties similar to the subject and for which there is normally no need. An example of a superadequacy would be the foundation of a house that is built with twice the support that is actually necessary. Buyers would typically not pay more for that construction, so an adjustment would not be warranted since the market does not recognize this as a value-adding asset.

Some adjustments are self-explanatory. For instance, when lot sizes vary, the adjustments for size are obvious. However, any adjustments that are not obvious should be explained, especially if they are large adjustments that have a significant effect on the value of the subject property. For instance, a large adjustment for functional utility or location should be explained in the comments section or somewhere in the appraisal. If the location of one of the comparable sales is next to a noisy freeway, the appraiser should state that this was the reason for the adjustment.

Although it might seem oversimplistic, it is important to remember that the appraiser does not make the comparable sales. The appraiser finds only what exists. Nevertheless, reviewers sometimes want to see better comparable sales. That may not be possible, however, if the appraiser has performed accurate market research and he or she has already utilized the most similar sales. When the market is slow, or when the property has special features or is nontypical in some way, comparable sales may be difficult to find, and the ones that are found may require large adjustments. In such cases, there are good reasons for large adjustments, and they do not necessarily mean that the appraisal has not been performed properly.

Assessment information typically includes the square footage of the home and land in the assessment records. As previously mentioned, the size of a home is one of the major characteristics that affect the value, which means the accuracy of the measurement is of paramount importance. The appraiser does not measure the comparable properties, but the appraiser should measure the subject property. If the size of the house in the appraisal varies a great deal from the size shown in the assessment records, this can mean one of several things.

It could mean that the appraiser made a mistake measuring the home, or it could mean that the appraiser from the assessor’s office made a mistake measuring the house. Rarely do two people get the exact same size when measuring a home, especially if it is a home with a lot of angles. A difference of 100 square feet or less would not be considered substantial, and it should not cause concern for the reviewer. In fact, because of variances due to human errors, many appraisers do not adjust for square footage differences of less than 100 square feet. But if the difference is larger than 100 square feet, the appraiser should have determined where the problem lies and made a note in the appraisal explaining it.

Another reason for the difference in size might be that the house was added on to, and the assessor’s records are not up to date. Normally when a building permit is granted, the assessor is notified and the record is changed to show the change in square footage, which also generally increases the property taxes. The assessor could have overlooked the permit, or the addition might be too new for the record to have been changed. Note that even if there has been a lag in reporting the addition, there should still be a record at the home showing that the building inspector approved the addition.

Whatever the reason may be, the appraiser should explain why there is a difference in a clear and concise way. Furthermore, the appraisal should be considered inaccurate until the explanation is given.

Sometimes a property does not conform to current zoning, and it cannot be rebuilt if it is destroyed by a fire or some other calamity. Since this can adversely affect the value, the appraiser, if aware of this, should explain the situation. Sometimes a letter stating that the property can be rebuilt may be required by a lender to finance a property with this issue. However, it is not the appraiser’s responsibility to produce such a letter, and there may be an expense in procuring one from the building department. The reviewer will want to do more research if this is an issue in an appraisal.

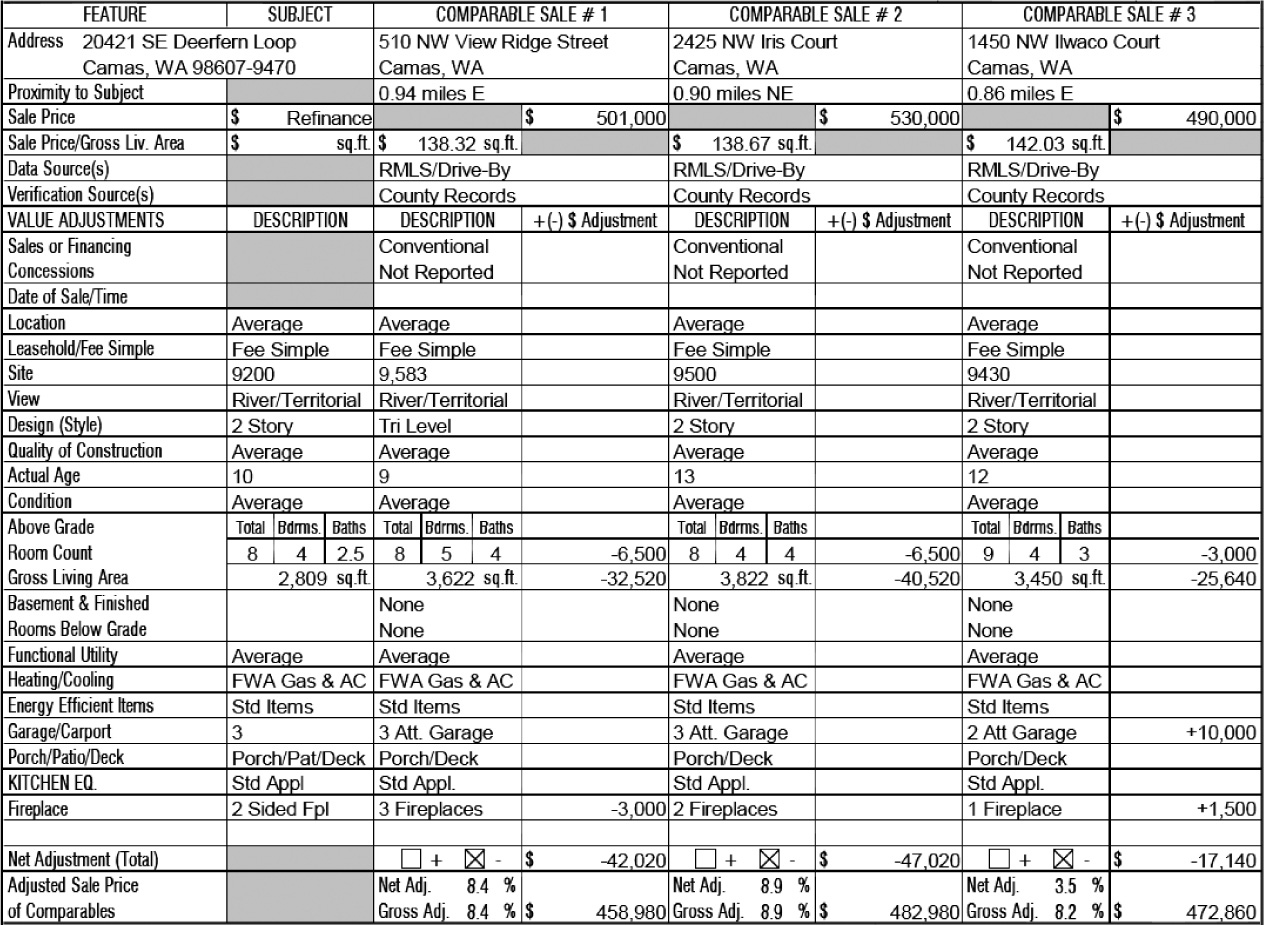

The following are examples of appraisals that are complex due to the difficulty of finding comparable sales that were similar to the subject. When comparable sales vary significantly from the subject property, adjustments are always a high percentage of the original sale price and are difficult to estimate. Not all complex appraisals are of high-value properties. The appraisal in Exhibits 2.7 and 2.8 was difficult because of the large amount of land the subject has.

Residential Appraisal That Is Complex Due to Land Size

Partial Notes for Comparable Sales for Appraisal in Exhibit 2.7

Properties on acreage are often difficult to appraise because the appraiser has to find sales that are similar in acreage size, as well as similar in building characteristics. In this case, the subject had 34.01 acres, but there were no other sales that could be found that were that large. Consequently, the appraiser found the largest parcels he could, and he adjusted them upward to make up for the size. Further complicating this valuation is the fact that the subject house is small—and is in fact half the size of sale 1 and one-third the size of sale 3. The adjustments are huge in this example, with gross adjustments over 75 percent for sales 1 and 3. Sale 3 is also 19.3 miles away, but according to the appraiser’s notes, there were no closer sales. There is also an easement for a very high frequency omnidirectional range (VOR) facility, which is a short-range radio navigation system for aircraft. The VOR easement affected the subject’s land value since nothing could be constructed within 1,000 feet of it.

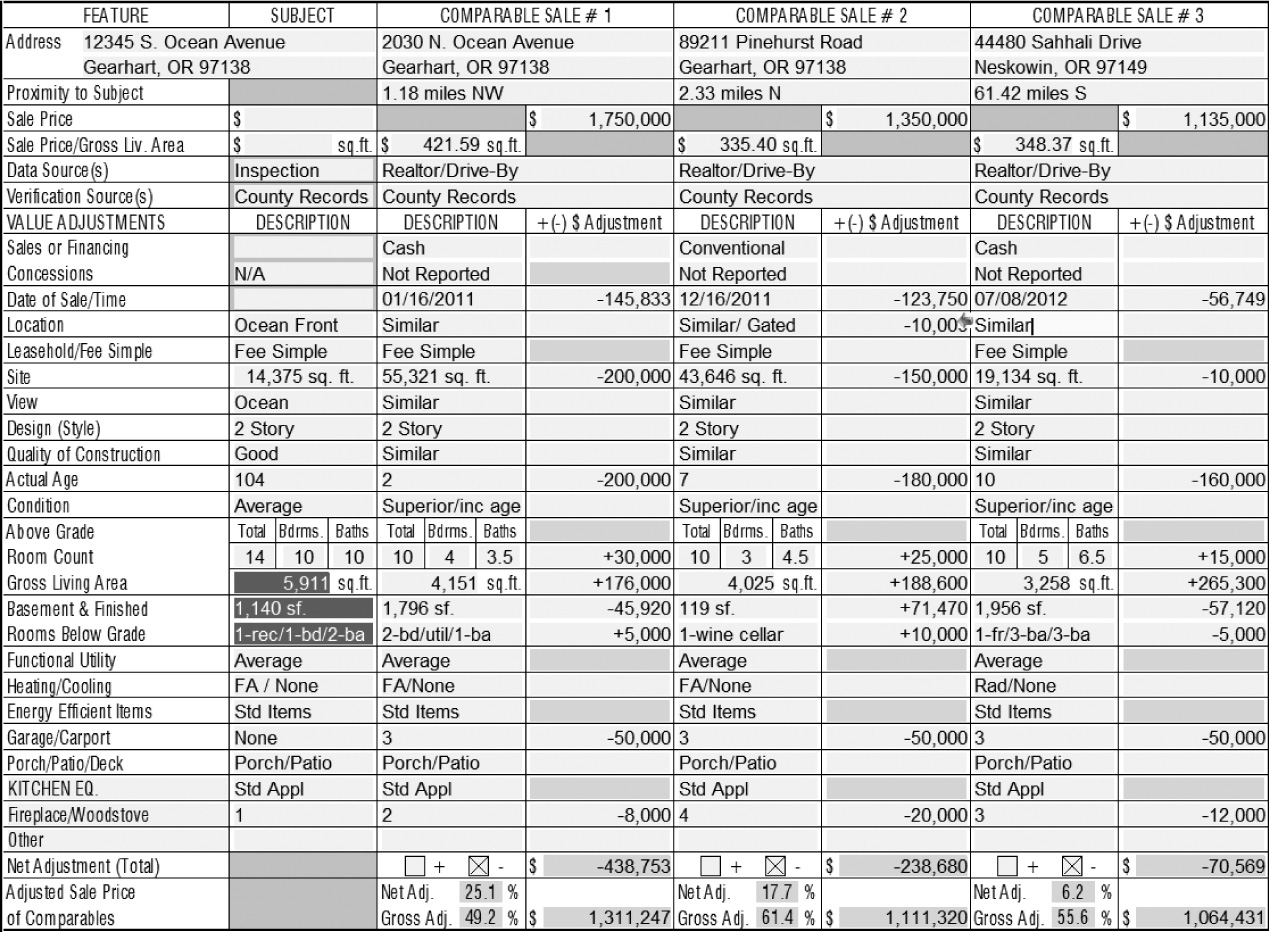

Exhibit 2.9 is an example of an appraisal for a high-value home. In this example, note that all the sales had to be large, oceanfront properties, which limited the choice of sales. One of the sales is over 60 miles away, but it is located in an area the appraiser deemed similar to the subject’s location. The percentage of adjustments is high, but this is to be expected with a property of this type. The appraiser’s notes shown in Exhibit 2.10 state that the comparable properties are newer and that the condition adjustment and the age adjustment have been combined. The subject property is an older home, but it has been remodeled and it is in good condition, although not comparable to the newer homes. To bolster the appraisal, the appraiser has included listings. In Exhibit 2.11, the appraiser explains some of the specifics about the subject home that affect its value in comparison to the comparable sales.

Residential Appraisal That Is Complex Because the Subject Is an Oceanfront Property

Partial Notes for Comparable Sales for Appraisal in Exhibit 2.9

Partial Notes Relating to the Subject Property in the Appraisal in Exhibit 2.9

In Exhibit 2.12, the listings, as opposed to sales in Exhibit 2.9, show the top of the market. In other words, there is no way to know what they will sell for, but they do establish the highest price they may sell for, although not the lowest. From this information the appraiser can get an idea of what the upper end of the market is, and in a market that is changing quickly, the listing information is particularly important. For instance, if the market is declining and the sales are six months old or older, in that six-month time period, prices may have dropped by 5 or 10 percent.

Residential Appraisal for High-Value Beach Property Listings Comparable to the Subject Property in Exhibit 2.9

Note that the appraiser has included a “listing to sale adjustment,” which is an estimate of how much the property may ultimately sell for after negotiations. In an accelerating market, houses may be selling for list price or close to it, or in some cases more than list price. However, in a declining market, which is the type of market this appraisal was performed in, the reduction from list price (asking price) may be large. This will probably be especially true for large beach homes because they are typically vacation homes. And in a declining market, the demand for homes that are not primary residences often drops more quickly because they are considered a luxury in deteriorating economic conditions.

For single-family home residential properties, the income approach is rarely used. However, if the property is being purchased as a rental home, an income approach analysis might be utilized. It would also be used for the purchase of rental homes by an investment entity, which might include multiple single-family residential properties owned in a portfolio. In such a case the income would be a primary consideration. A discussion of the income approach can be found in Chapter 5 on commercial appraisals.