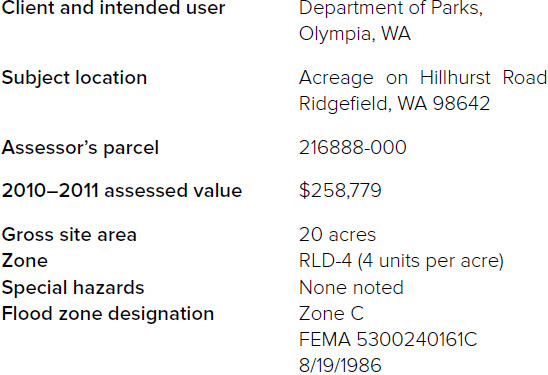

Executive Summary

4

Summary Appraisal Report

The sales comparison approach is the only method that can be used for land appraisals unless the land is leased or in some other way produces income. Land is sometimes leased for grazing, parking, or other uses. However, when it is leased for structures, the lease is generally long term—often for 20 years or more—and leases of this type are more common in other countries than in the United States.

With long-term leases, the lessee may build a structure, and generally the ownership of the structure goes to the lessor at the end of the lease. A typical lease for land in the United States would be for a cell tower. Depending on the agreement, the lease may require the lessee to remove the tower at the end of the lease or the tower may become the lessor’s property when the lease terminates.

The income approach for appraising leased land will not be covered here because Chapter 5, the commercial appraisal chapter, will go over it, and the same principles are applicable. The example in that chapter applies to any income stream, whether it comes from a lease or another source.

Land valuations can be relatively simple if the valuation is for a lot in a subdivision where others that are similar have sold. However, for many land appraisals, there are myriad aspects that must be considered that are specific and often unique for each parcel under valuation. And, like the proverbial snowflake, the more closely comparable land sales are examined, the more apparent their differences become. Moreover, the complexity of land sales seems to rise relative to the land regulations of the state in which they occur. The more environmentally active states tend to have more rules limiting development, and they allow more avenues of recourse for those organizations and state agencies that challenge development.

Some of the issues the appraiser has to consider are wetlands, protected species, environmental contamination, noise and pollution, drainage, traffic restrictions (also known as concurrency), building moratoriums, and citizen pressure. All of these issues are set against a backdrop of dealing with various echelons of government—federal, state, and local—some of which are redundant in the areas they regulate and may use different yardsticks in their determinations.

For this reason, the fact that land is zoned for a particular use does not mean that its development is realistic or cost effective. For instance, a small parcel of land that is two acres in size may be zoned for 6,000-square-foot lots. However, once the easements for access are considered, and the engineering and other development fees are calculated, in addition to the time that the property must be held to get the permits approved, there may be no profit in the venture.

For this reason, developers pay a premium for prime land, which normally means land that has been approved for construction and has already been through the permitting process.

Land values can also change quickly and significantly depending on hearings that may be held regarding potential usage in various tribunals, or by local politicians. (For more information, also see the segment on land valuation in Chapter 7 on industrial building appraisal.)

When development is at low ebb due to economic conditions or other circumstances that have lessened demand, there may be very few buyers for land, and prices may fall precipitously. However, the appraisal may not reveal this clearly because sales may be used that are older, and adjustments for those sales may not have kept up with the diminished demand. Listings also may not reveal the extent of the drop in value because they often stay higher than market value as compared to other real estate. The reason for this is that landowners often own their property free and clear and are under less pressure to sell than the owners of other types of real estate.

Red Flag

In a declining market, land appraisals can be inflated because often landowners are not under the same compulsion to sell as homeowners who need to move, perhaps because of lost employment. This means land listings may be much higher than actual market values, and if older sales are used due to a lack of current sales, those transactions may not reflect the current market. Consequently, if proper adjustments are not made for the elapsed time from the date of sale for the comparable sales, the appraisal may be higher than market value. The lack of recent sales may also portend a market that has become stagnant.

However, in an appraisal in a declining market, the appraiser may not be attempting to inflate the value. The appraiser works only from the data that is available. If there are few sales and they are older, the indicated value of the subject property may be inaccurate only because there have been no recent sales that reflect the change in values, and the appraiser has no other valuation evidence to use.

Conversely, when values are climbing because demand has increased, even sales that are six-months or a year old may not reflect the current value. Appraisers may know that values are increasing in such a market, but they must work from actual sales as evidence of the value, and higher listings do not provide evidence that can be used in the appraisal to prove a value. Essentially the appraiser’s hands are tied in such a market, and the value may come in lower than the sale price due to the rapidly increasing market.

PROPERTY

Vacant residential land

Parcel number 216888-000

20-acre parcel

May 11, 2012

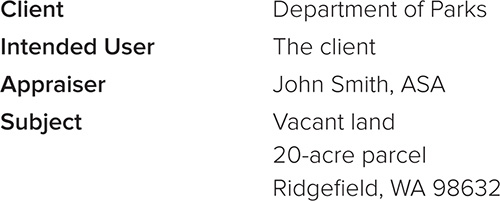

PREPARED FOR

Department of Parks

Attention: Mr. Ralph Jones

Administrator

230 Acacia Avenue

Olympia, WA 98642

PREPARED BY

Expert Appraisals, Inc.

John Smith, ASA

702 NE 19th Circle

Ridgefield, WA 98642

(360) 111-1111

1

At your request, I have prepared an appraisal of the Ridgefield land identified by the assessor as parcel number 216888-000, which is currently a 20-acre parcel. The purpose of this appraisal is to estimate the subject’s as-is fee simple market value, for the possible purchase of the property. The market value conclusion is predicated on an 18-month exposure period.

This report has been prepared in conformance with the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice (USPAP) as formulated by the Appraisal Foundation. Further, this report is prepared in conformance to the Appraisal Standards for the American Society of Appraisers.

Please refer to the Assumptions and Limiting Conditions section of the attached report for an explanation of the basis on which the value conclusion is predicated. The signatory of this report is qualified by experience and education to competently appraise the subject property. The values reported in this appraisal are not contingent on the approval of a specific loan amount or any other circumstance. This appraisal was not performed to reach a predetermined value or predetermined value range.

I conclude, based on the analysis contained in this report, the subject property had an as-is rounded fee simple value, as of May 11, 2012, of

FOUR HUNDRED TWO THOUSAND DOLLARS ($402,000)

The basis for this value conclusion will be explained in the contents of the attached appraisal report.

Sincerely,

John Smith, ASA

Washington State

Certified General

Appraiser 1100000

2

Summary Appraisal Report

Purpose, Function, and Scope of Appraisal

Assumptions and Limiting Conditions

Special Assumptions and Limiting Conditions

Summary of Analysis and Valuation

Discussion and Conclusions of Value

Real Property Value Conclusion

Photographs of Subject Property

Summary Appraisal Report

3

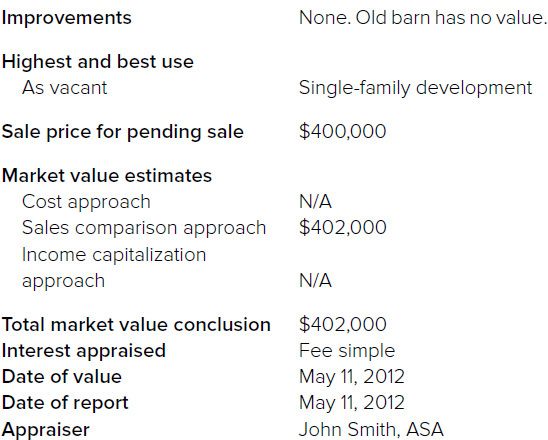

Map of Subject Property—Approximate, Not Actual, Address

Map of the Subject Property, Parcel Number 216888-000, on Record with the County Assessor

Summary Appraisal Report

5

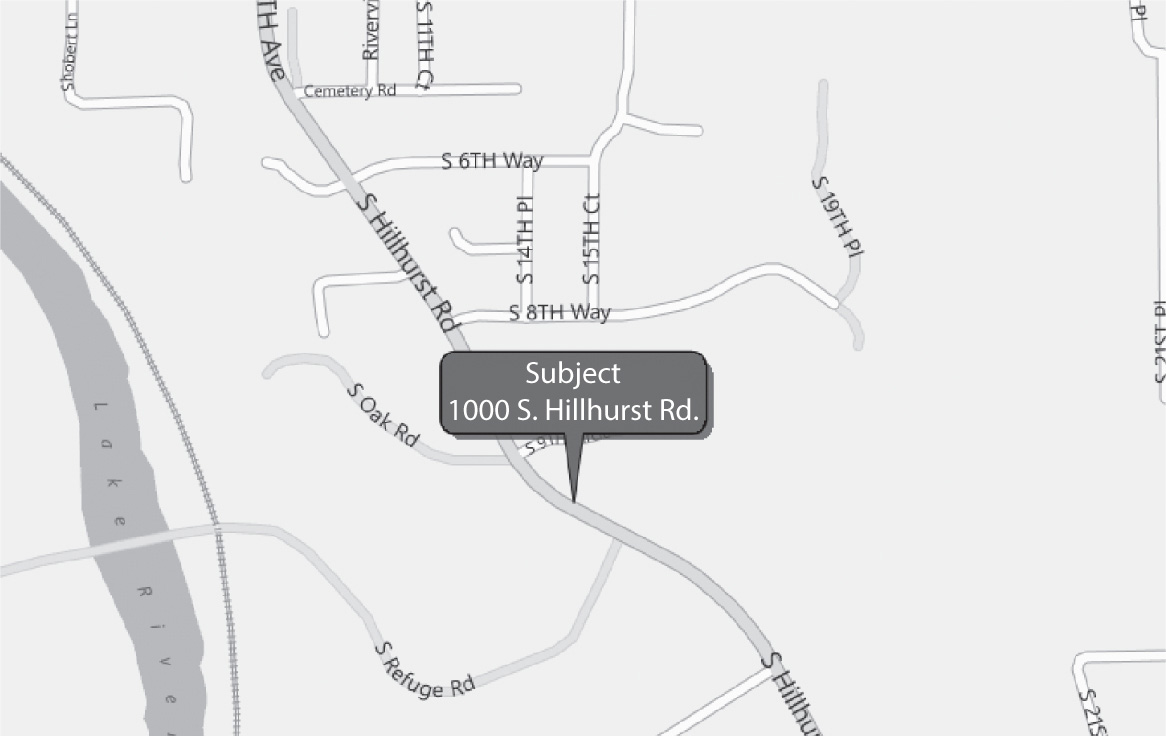

Aerial Map of the Subject Property, Parcel Number 216-888-000, on Record with the County Assessor

This is a summary appraisal report, which is intended to comply with the reporting requirements set forth under Standards Rule 2-2(b) of the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice for a Complete Appraisal presented in Summary Form. As such, it presents summary discussions of the data, reasoning, and analyses that were used in the appraisal process to develop the appraiser’s opinion of value. The depth of discussion contained in this report is specific to the needs of the client and for the intended use stated below.

I have appraised this property previously, and that appraisal is in the possession of my client. The appraiser is not responsible for unauthorized use of this report. This report is the result of a full appraisal process. The sales comparison approach is the only applicable valuation approach for this assignment. The value opinion is based on current understanding of the market and market trends.

6

Summary Appraisal Report

The purpose of this appraisal is to provide the appraiser’s best estimate of the subject’s as-is fee simple market value. The use of this appraisal is to aid the Department of Parks to determine the price the Department may want to pay for the land.

Market value is defined by the federal financial institutions regulatory agencies as follows:

Market value means the most probable price which a property should bring in a competitive and open market under all conditions requisite to a fair sale, the buyer and seller each acting prudently and knowledgeably, and assuming the price is not affected by undue stimulus. Implicit in this definition is the consummation of a sale as of a specified date and the passing of title from seller to buyer under conditions whereby:

1. buyer and seller are typically motivated;

2. both parties are well informed or well advised, and acting in what they consider their own best interests;

3. a reasonable time is allowed for exposure in the open market;

Summary Appraisal Report

7

4. payment is made in terms of cash in U.S. dollars or in terms of financial arrangements comparable thereto; and

5. the price represents the normal consideration for the property sold unaffected by special or creative financing or sales concessions granted by anyone associated with the sale.

(Source: Office of the Comptroller of the Currency under 12 CFR, Part 34, Subpart C-Appraisals, 34.42 Definitions [F].)

This appraisal is intended to assist the client, the Department of Parks, in decision making concerning a possible land purchase. The use of this report is restricted to the client only, who is the intended user. The depth of discussion contained in this report is specific to the needs of the client and for the intended use stated herein. The appraiser is not responsible for unauthorized use of this report. Regardless of who pays for this appraisal, the intended user is the client only.

The scope of work in this appraisal has been customized for the intended user. It may be inappropriate for other users and put them in jeopardy. Therefore, regardless of the means of possession of the report, this appraisal may not be used or relied on by anyone other than the stated intended user. The appraiser, appraisal firm, and related parties assume no obligation, liability, or accountability to any third party. If you are not the stated intended user, please contact my office to have an appraisal customized for your needs.

There is currently an offer of $400,000 on the subject property, and the sales contract was analyzed by the appraiser.

8

Summary Appraisal Report

The appraiser has valued the fee simple ownership interests in the subject property. The subject is a 20-acre parcel.

May 11, 2012

May 11, 2012

In preparing this appraisal, the appraiser:

• Inspected the subject site and walked on the land.

• Gathered and confirmed information on comparable improved sales. The appraiser considered all three approaches and applied all applicable approaches to arrive at an indication of value.

Three basic approaches are typically used to estimate market value: (1) the cost approach, (2) the sales comparison (market) approach, and (3) the income capitalization approach.

1. As agreed on with the client prior to the preparation of this appraisal, this appraisal conforms to the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice (USPAP) and the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act of 1989 (FIRREA).

Summary Appraisal Report

9

2. This is a summary appraisal report, which is intended to comply with the reporting requirements set forth under Standards Rule 2-2(b) of the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice for a summary appraisal report. As such, it might not include full discussions of the data, reasoning, and analyses that were used in the appraisal process to develop the appraiser’s opinion of value. Supporting documentation concerning the data, reasoning, and analysis is retained in the appraiser’s file. The information contained in this report is specific to the needs of the client and for the intended use stated in this report. The appraiser is not responsible for unauthorized use of this report.

3. No responsibility is assumed for legal or title considerations. Title to the property is assumed good and marketable unless otherwise stated in this report.

4. The property is appraised free and clear of any or all liens and encumbrances unless otherwise stated in this report.

5. Responsible ownership and competent property management are assumed unless otherwise stated in this report.

6. The information furnished by others is believed to be reliable. However, no warranty is given for its accuracy.

7. All engineering is assumed to be correct. Any plot plans and illustrative material in this report are included only to assist the reader in visualizing the property.

8. It is assumed that there are no hidden or unapparent conditions of the property, subsoil, or structures that render it more or less valuable. No responsibility is assumed for such conditions or for arranging for engineering studies that may be required to discover them.

10

Summary Appraisal Report

9. It is assumed that there is full compliance with all applicable federal, state, and local environmental regulations and laws unless otherwise stated in this report.

10. It is assumed that all applicable zoning and use regulations and restrictions have been complied with, unless a nonconformity has been stated, defined, and considered in this appraisal.

11. It is assumed that all required licenses, certificates of occupancy, or other legislative or administrative authority from any local, state, or national governmental or private entity or organization have been or can be obtained or renewed for any use on which the value estimates contained in this report are based.

12. Any sketch in this report may show approximate dimensions and is included to assist the reader in visualizing the property. Maps and exhibits found in this report are provided for reader reference purposes only. No guarantee to accuracy is expressed or implied unless otherwise stated in this report. No survey has been made for the purpose of this report.

13. It is assumed that the utilization of the land and improvements is within the boundaries or property lines of the property described and that there is no encroachment or trespass unless otherwise stated in this report.

14. The appraiser is not qualified to detect hazardous waste and/or toxic materials. Any comment by the appraiser that might suggest the possibility of the presence of such substances should not be taken as confirmation of the presence of hazardous waste and/or toxic materials. Such determination would require investigation by a qualified expert in the field of environmental assessment. The presence of substances such as asbestos, urea-formaldehyde foam insulation, or other potentially hazardous materials may affect the value of the property. The appraiser’s value estimate is predicated on the assumption that there is no such material on or in the property that would cause a loss in value unless otherwise stated in this report. No responsibility is assumed for any environmental conditions, nor is any responsibility assumed for any expertise or engineering knowledge required to discover them. The appraiser’s descriptions and resulting comments are the result of the routine observations made during the appraisal process.

Summary Appraisal Report

11

15. Unless otherwise stated in this report, the subject property is appraised without a specific compliance survey having been conducted to determine if the property is or is not in conformance with the requirements of the Americans with Disabilities Act. The presence of architectural and communications barriers that are structural in nature that would restrict access by disabled individuals may adversely affect the property’s value, marketability, or utility.

16. Any proposed improvements are assumed to be completed in a good workman-like manner in accordance with the submitted plans and specifications.

17. The distribution, if any, of the total valuation in this report between land and improvements applies only under the stated program of utilization. The separate allocations for land and buildings must not be used in conjunction with any other appraisal and are invalid if so used.

12

Summary Appraisal Report

18. Possession of this report, or a copy thereof, does not carry with it the right of publication. It may not be used for any purpose by any person other than the party to whom it is addressed without the written consent of the appraiser, and in any event, only with proper written qualification and only in its entirety.

19. Neither all nor any part of the contents of this report (especially any conclusions as to value, the identity of the appraiser, or the firm with which the appraiser is connected) shall be disseminated to the public through advertising, public relations, news, sales, or other media without the prior written consent and approval of the appraisal.

20. This report must be used in its entirety. Reliance on any portion of the report independent of the report as a whole may lead the reader to erroneous conclusions regarding property values. No portion of this report stands alone without express written approval from the author.

21. The liability of Expert Appraisals, Inc., and its employees is limited to the client only and only up to the amount of the fee actually received for the assignment. Further there is no accountability, obligation, or liability to any third party. If this report is placed in the hands of anyone other than the intended users, the client shall make such party aware of all limiting conditions and assumptions of the assignment and related discussions. The appraiser is in no way responsible for any costs incurred to discover or correct any deficiency in the property. The appraiser assumes that there are no hidden or unapparent conditions relating to the property that render it more or less valuable.

Summary Appraisal Report

13

22. The subject property in this appraisal is identified primarily by the assessor’s map and tax lot as put forth in the body of this report or by other descriptions found in the body of this report if the assessor’s map and tax lot are not applicable. Any other legal description found in the body or addenda of this report has been placed there as a courtesy and should not be viewed as the primary identifier of the property. These descriptions have been provided by the client or a title company and have not been prepared or verified by this office. I am not a surveyor, and it is beyond the scope of this appraisal to verify metes and bounds legal descriptions.

23. Due to various considerations including timing and distance, some photographs and maps and drawings in this report may have been taken or made by others. Typical sources include multiple listing services, real estate agents’ marketing brochures, county assessor’s records, LoopNet, Google, Oregon Water Resources Department, USDA web Soil Survey, FEMA, OrMap, county planning departments, and other sources. In all cases the comparables were investigated by this appraiser and inspected and investigated adequately, either in person or through published sources, and/or personal verifications to provide the appraiser a good understanding of the comparability of the property comparable to the subject.

14

Summary Appraisal Report

This valuation is based on an existing 20-acre parcel that may have wetlands or other environmental issues. The appraiser was not given any reports, analyses, studies, or wetlands delineations regarding these matters, and the appraiser assumes no responsibility for the amount of usable land for the subject property, or the potential use for dividing or building on the subject property, and will be held harmless regardless of the final determinations by government officials and others regarding the usability of the subject property.

This report complies with USPAP requirements as well as Interagency Appraisal and Evaluation Guidelines. It is a full appraisal assignment.

I am aware of and knowledgeable about the Competency Provision as set forth by the USPAP. The firm of Expert Appraisals, Inc., and John Smith, ASA, more specifically, has performed appraisals of comparable properties in recent years.

The definition of market value as used in this report is given in the Purpose of the Appraisal section of this report.

Summary Appraisal Report

15

This appraisal is a summary report stating the appraiser’s opinion as to the fee simple value of the subject property. The report format presents the data and analysis that contributed to the value conclusions, and additional data and analysis are retained in my files.

This is not applicable to the subject property because it is vacant land.

Market exposure has been estimated based on current market data. I estimate a market exposure for the subject property of approximately 18 months.

The current state of the national and state economy is such that sales of real estate have been very slow, and as a result overall real estate values are in state of decline.

In the last five years, only quit claim deeds without a value indicated have been recorded on this parcel, from the county records.

A legal description of the subject property has been found from the assessor’s records, but I assume no responsibility for matters legal in character, nor do I render any opinion as to the title, which is assumed to be good. I have not surveyed the property and assume no liability for such matters. If any metes and bounds description or other legal description of the subject appears in the body or addenda of this report, it appears as a courtesy and should not be relied upon for legal purposes. I am not a surveyor and cannot determine the accuracy or sufficiency of metes and bounds legal descriptions or of the assessor’s legal descriptions.

16

Summary Appraisal Report

The property does not require specific discounts or deductions in the valuation process. No deductions or discounts were used to arrive at a final value conclusion with the exception that the cost to remove the mobile home according to my client’s suggestions has been taken into account.

This appraisal includes a signed certification page from John Smith, ASA, certifying that he meets the current appraisal standards mandated by federal law and the USPAP. None of the value conclusions presented in this appraisal were based on a requested valuation. In my opinion, they are true, unbiased market values. I have taken into consideration the information, concerns, and opinions given me by the client. However, I have not altered or skewed my opinion of value to favor any individual or group of people.

Summary Appraisal Report

17

This appraisal does not include personal property, freestanding equipment, rolling stock, inventories, mobile homes, or any intangible items such as business value.

This appraisal follows a reasonable valuation method that employs the sales comparison approach as applicable to value the subject property. Neither the cost approach nor the income capitalization approach is applicable to this appraisal.

The subject is located in Ridgefield, Washington, which is a bedroom community to Vancouver, Washington. The community includes subdivisions and residential properties on acreage, as well as retail, commercial, and industrial sections.

The subject is a 20-acre parcel. The subject is rolling terrain, mostly dry from appearance, and it borders Hillhurst Road. The shape is irregular. Zoning is RLD-4 which allows four units per acre.

This appraisal assumes no hazardous materials are in the subject property. Prior to further development, the potential for hazardous materials should be fully explored by a qualified engineering firm. I am not qualified to detect hazardous materials and make no affirmation as to the presence or absence of such in regards to the subject property.

18

Summary Appraisal Report

There are no usable improvements on the subject property, and for development purposes, utilities would have to be brought in.

Note to Reader: Typically an area analysis does not need to be read by the reviewer, unless the reviewer is not familiar with the subject’s geographical location. Often appraisals will be filled with statistics and other chamber of commerce type of information that can be skimmed over or ignored.

The subject is located in Ridgefield, Washington, in Clark County. It is close to the Interstate 5 and is in the north end of the county, and it is convenient to the major freeways I-5 and I-205. The Clark County area is part of the larger Portland/Vancouver primary metropolitan statistical area (PMSA).

This area comprises various counties including Multnomah, Clackamas, Washington, and Yamhill Counties in Oregon and Clark County in Washington. Many of the residents of Clark County have employment in the Portland, Oregon, area, and some Oregon residents also work in Clark County. The Portland/Vancouver PMSA is the largest population center on the West Coast between Seattle and San Francisco, and it is rated as the thirty-first largest metropolitan area in the United States, and the eighth largest in the northwestern and western portion of the United States.

Summary Appraisal Report

19

The population of Vancouver, according to the Clark County 2010 estimate, is 161,791. The area has been known for low unemployment until about 2007, when property values declined and unemployment increased into the double digits. Ridgefield’s 2010 population was 4,763 in 2010.

The property sales indicate that exposure time (that is, the length of time the subject property would have been exposed for sale in the market had it sold at the market value concluded in this analysis as of the date of this valuation) would have been from 6 to 18 months. The estimated marketing time (that is, the amount of time it would probably take to sell the subject property if exposed in the market beginning on the date of this valuation) is estimated to be 18 months if marketed at the value as concluded in this report.

Because of the current declining market, the client should be aware that if the subject marketing period is extended, the sale price could reasonably be expected to be below this appraised value even within the one-year typical marketing period.

Note to Reader: Assessment information should be included in the appraisal, although it is not required. It is not unusual for the assessor’s value to differ significantly from the appraiser’s value, and it does not necessarily indicate an error in the appraisal. The reason is that assessors often use mass appraisal techniques that are not specific to the property, and they generally lack the staff to keep the values current.

20

Summary Appraisal Report

The 2011 values for 2012 taxes from the assessor’s office show a total value of $258,779.

To my knowledge, unless stated, none of the comparable sales included personal property, business value, goodwill, or other non–real estate goods. Unless otherwise noted, the sale price of each comparable is attributable to the real property only. See comments in the sales narrative concerning adjustments made to some sales. I have considered this factor qualitatively in my analysis.

Each sale involved the transfer of fee simple interest from grantor to grantee. No adjustments for property rights were necessary.

Adjustments for financing are sometimes necessary depending on the terms of a contract. Sellers sometimes inflate the sale price and offer attractive atypical contract terms. Also conversely, contract terms, which are above market rates, may reduce the cash equivalent sale price of a property. However, buyers are often protective of the terms of sale and are unwilling to release this information. Of the comparable sales used in the sales comparison, all were sold for cash or for terms I deemed as cash equivalent. Because of this, no cash equivalency adjustment was necessary.

Summary Appraisal Report

21

Based on my research, the sales appear to be arm’s-length transactions in which neither the buyer nor the seller was under undue influence to consummate the sale.

A market conditions adjustment is best supported by a general market analysis and a paired-sales analysis. However, a paired-sales analysis is effective only when at least two sales are similar in nearly all respects, except for the date of sale. A difference between the unit values can be attributed to changes in the marketplace during the time between the two sales. My conversations with real estate brokers, county officials, and other appraisers have led me to believe that the market for property such as the subject has decreased approximately 10 percent annually over the time span of the comparable sales execution dates to the present. One of the problems in this adjustment is that there have been so few sales of similar properties in Ridgefield and the surrounding area.

The sales were weighted accordingly for differences as needed. For instance, the land sales were adjusted quantitatively for size, zone, and location as well as market conditions and for its being a listing because listings often sell for less than their listed prices.

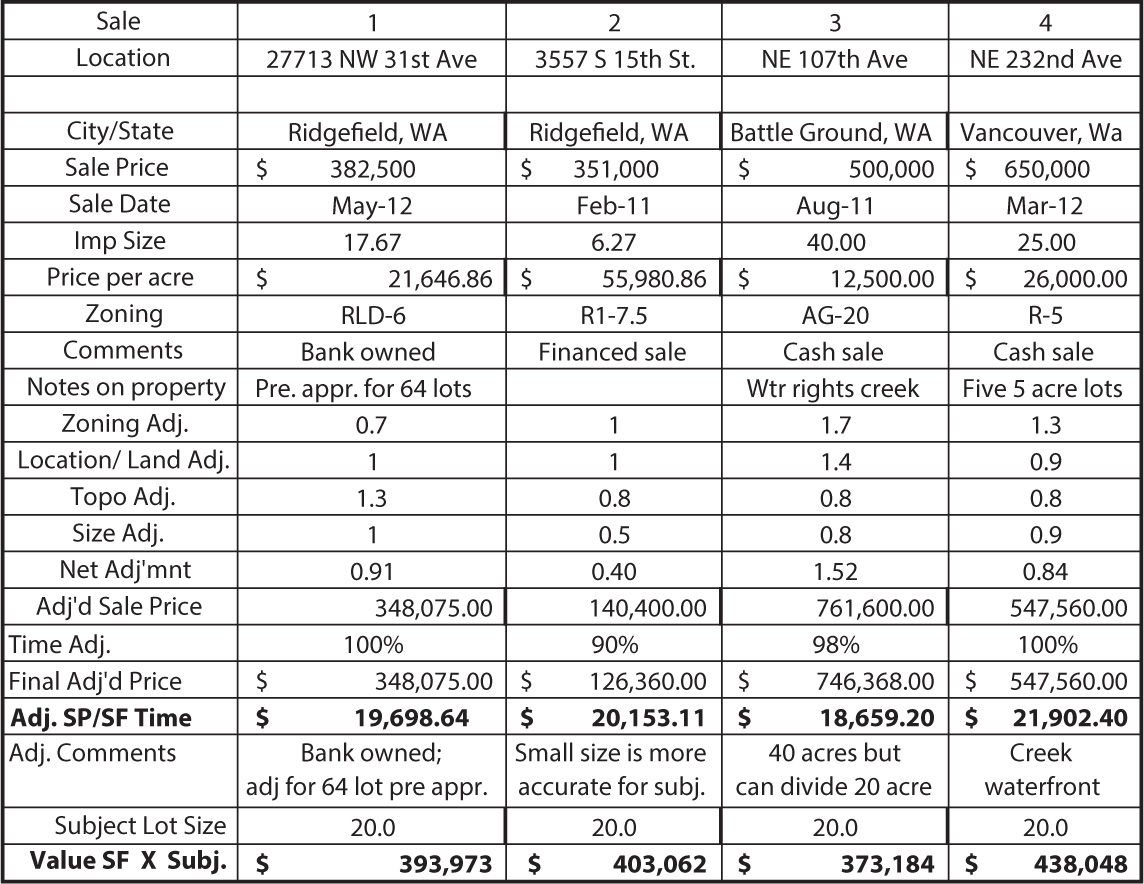

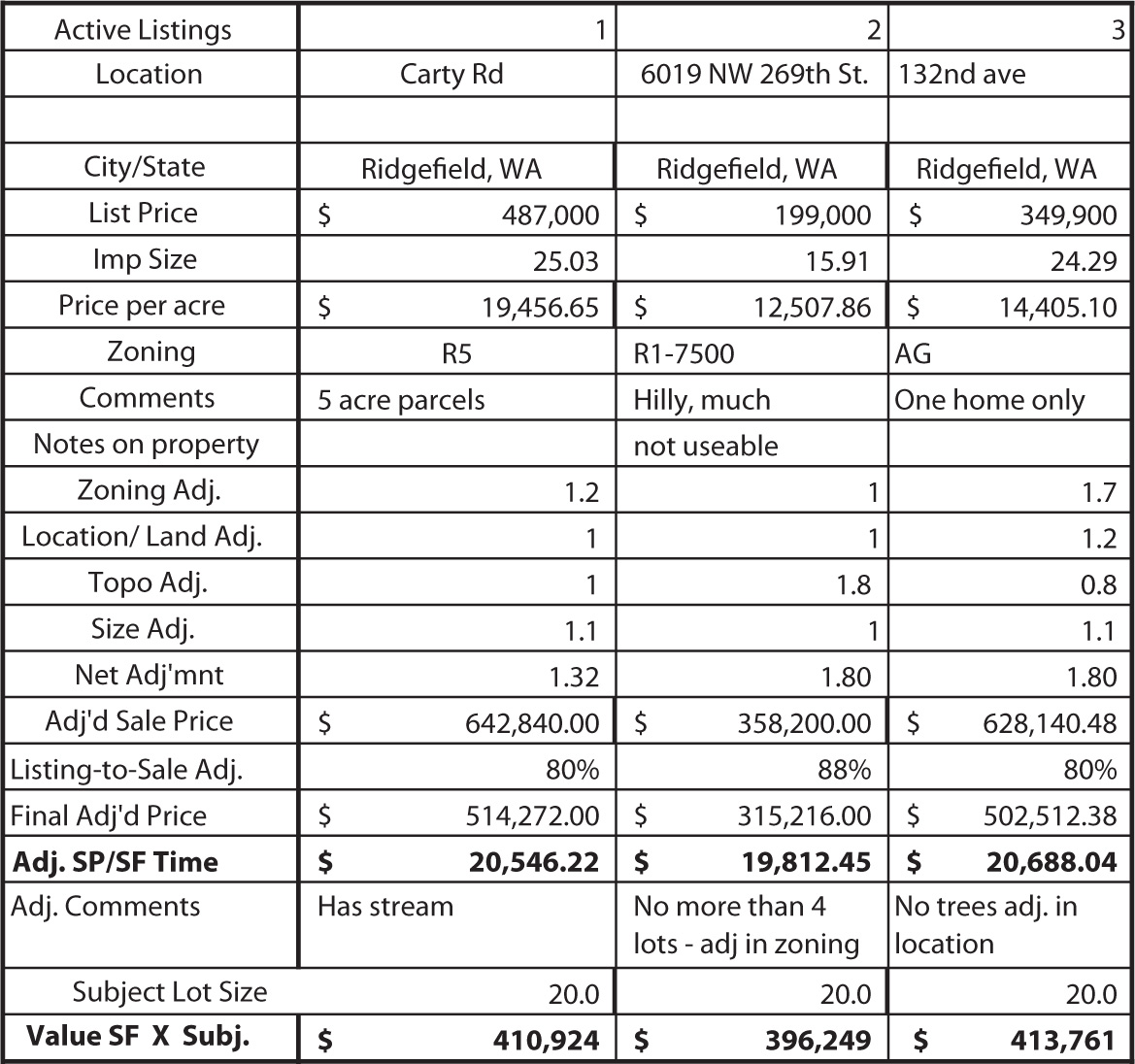

The sales comparison approach was used exclusively for this property because it is vacant land. The following show the sales used in the appraisal, as well as listings of properties that are for sale. Please note that listings indicate the highest value a property would sell for and that in the current market, which has been declining for several years and has not yet recovered, the list price for many properties may be well over the final actual sale price. A listing-to-sale adjustment has been made for the listings, which is the appraiser’s opinion of the likely sale price that may be received.

22

Summary Appraisal Report

Because the market is very slow, there were few sales to use for this appraisal, and an expanded search included sales in Vancouver and nearby areas. The subject is zoned for development, but because of current economic conditions, land has been selling for less than its normal development value. Some sales are not developable, and others are dividable only into two parcels. Therefore, appropriate adjustments were made under the zoning adjustment on the grid.

Sales Comparable to Subject Property

Summary Appraisal Report

23

Listings Comparable to Subject Property

The land comparables vary in location, size, and timing, but all are generally helpful in estimating the subject value.

After a qualitative and quantitative analysis of these sales, I believe that a value of $20,100 per acre for the land as if vacant is supported and reasonable. The total land value would therefore be as follows:

20 acres × $20,100 = $402,000

24

Summary Appraisal Report

Note to Reader: It is common for the appraiser to discuss each of the comparable sales as part of the analysis, but that was not done in this appraisal. The lack of a discussion does not necessarily mean the appraisal is lacking, but it would have been preferable to get a little more information about each sale to understand the appraiser’s reasoning for the adjustments for the sales.

Based on the data and analysis presented, I therefore conclude the sales comparison approach yields a fee simple market value, as of May 11, 2012, of:

$402,000

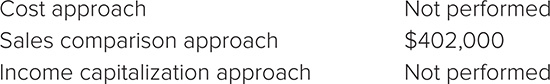

The vacant lot is valued by the sales comparison approach only, and that is the only applicable approach for this lot.

The cost approach was inapplicable to this assignment.

The sales comparison approach is closely tied to the marketplace, and there was adequate data to support the land value and improved value conclusions by this approach.

The income capitalization approach was not performed in my valuation because the subject is not primarily an income producing property and because the client has requested a land-only appraisal. Therefore, I have placed all weight on the conclusion of the sales comparison approach.

Summary Appraisal Report

25

I therefore conclude the subject property has an as-is fee simple market value, as of May 11, 2012, of:

Four Hundred Two Thousand Dollars

The following are photographs of the subject property from different perspectives.

Property from Southeast Corner of Easement

26

Summary Appraisal Report

Looking West from South End of Property (South Great Blue Road)

Looking South, Land on Right

Summary Appraisal Report

27

Looking North from Great Blue Road (South End of Land)

Looking West, Middle of Parcel

30

Summary Appraisal Report

Looking North from the South End of Land

The undersigned does hereby certify that, except as otherwise noted in this appraisal report, to the best of my knowledge:

1. The statements of fact contained in this report are true and correct.

2. The reported analyses, opinions, and conclusions are limited only by the reported assumptions and limiting conditions, and they are my personal, unbiased professional analyses, opinions, and conclusions.

3. I have no present or future interest in the property that is the subject of this appraisal, and I have no personal interest or bias with respect to the parties involved.

Summary Appraisal Report

31

4. My compensation is not contingent on an action or event resulting from the analyses, opinions, or conclusions in, or the use of, this report.

5. My analyses, opinions, and conclusions were developed, and this report has been prepared, in conformity with the requirements of the Code of Professional Ethics and the Standards of Professional Practice of the Appraisal Institute.

6. The use of this report is subject to the requirements of the Appraisal Institute relating to review by its duly authorized representatives.

7. As of the date of this report, I, John Smith, have completed the requirements under the continuing education program of the American Society of Appraisers.

8. I have made a personal interior and exterior inspection of the property that is the subject of this report. I have inspected the exterior and investigated all comparable sales used in this report.

9. No one provided significant professional assistance to the persons signing the report.

10. I do not authorize the out-of-context quoting from or partial reprinting of this appraisal report. Further, neither all nor any part of this appraisal report shall be disseminated to the general public by the use of media for public communication without my prior written consent.

11. This appraisal is prepared in conformance with the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice (USPAP) as promulgated by the Appraisal Standards Board of the Appraisal Foundation. The departure provision does apply.

32

Summary Appraisal Report

12. My employment was not conditioned upon the appraisal producing a specific value or a value within a given range. Future employment is not dependent upon reporting a specified value. Neither employment nor compensation is dependent upon the approval of a loan application.

13. I have acquired through study and practice the necessary knowledge and experience to complete this assignment competently.

14. I have appraised a portion of this property previously.

John Smith, ASA

WA Certification No. 1100000

John Smith, ASA

Certified General Appraiser

Professional Experience

Jacobs and Company Appraisers and Consultants

Vancouver, WA

2000 to 2010

Clark County Assessor

Commercial Appraiser

Vancouver, WA

1991 to 2000

Summary Appraisal Report

33