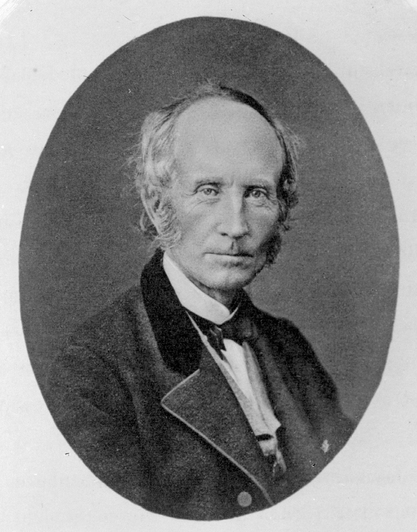

Hinrich Johannes Rink (1819–1893; Figure 2.1) is widely recognized as one of the founding fathers of Eskimology. A scholar with an impressive list of scientific publications, he was also a very influential member of the administration that at the time governed Denmark’s colonial empire in Greenland. This chapter explores four of Rink’s contributions to the study of Greenlandic and Inuit cultures: his empirical approach to research, his theory about the original cultural homeland of the Inuit, his views on the destructive impact that excessive Westernization had on Greenlanders, and a pioneer concept of the beneficent influence of shamans and drum songs on the rule of law and social order in Greenland’s precolonial society. In all of these fields Rink was far ahead of his time, and his political priorities and interests as a high-ranking colonial administrator not only stimulated but also deeply influenced his study of the Greenlanders’ past and present situation.

Born in 1819 and raised in a well-to-do family in Copenhagen, Rink studied physics and chemistry at the University of Copenhagen, where his thesis won a gold medal in 1843. After receiving his doctorate from the University of Kiel in 1844, he continued his studies—this time in medicine—at the University of Berlin, until 1845, when he joined the scientific crew of the Danish Navy vessel Galathea, which circumnavigated the globe from 1845 to 1847.

While the Galathea berthed in the Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal, one of Denmark’s overseas possessions at that time, Rink carried out geographical investigations until a bout of malaria forced his return to Denmark. He subsequently published—in German and a shortened version also in Danish—a topographical description of the islands (Rink, 1847a, 1847b), which was well received by the scientific community. In addition to describing the topography of the Nicobar Islands, Rink compared the culture of the islanders with what he at the time knew about the culture of the Greenlanders.

Figure 2.1 Hinrich Johannes Rink, 1819–1893 (undated photo). Danish Arctic Institute; image 06127.

It is the forest of coco nut trees which almost exclusively forms the life of the inhabitants. One frequently hears that if a certain nation has only attained to a low level of culture, this is because its existence is based on the utilization of one resource only. Because of this, the culture of such a nation displays a certain uniformity and its further development is submitted to severe restrictions. In this respect, one can compare the Greenlanders’ relation to the seal to the Nicobarians’ relation to the coco nut (Rink, 1847b:133).1

Rink’s research brought him to the attention of the Danish government, which was interested in exploring a graphite deposit near Uummannaq in North Greenland to determine if it could be profitably mined. The government therefore hired Rink in 1848 to carry out a three-year expedition to investigate North Greenland’s mineral resources. From this time until he retired from active service in 1881, Rink was employed by the special state agency that ruled Denmark’s colonial empire in West Greenland, the Royal Greenland Trade Department (RGTD).

When Rink returned to Copenhagen in 1851, he was appointed secretary to a royal commission that evaluated Denmark’s colonial policy in Greenland. He spent the summer of 1852 visiting the Danish colonies in South Greenland, which resulted in the publication of a booklet in which he defended the RGTD’s trade monopoly against its critics (Rink, 1852b). In 1853, the RGTD appointed him chief factor in Qaqortoq (then called Julianehåb), the southernmost of the 13 Danish colonies in West Greenland, followed by an 1855 appointment as acting governor (inspektør in Danish) in Greenland’s Southern Province, where he lived in the capital of Nuuk (then known as Godthaab).2 He was promoted to the position of the permanent governor in 1857, but health problems forced his return to Denmark in 1868. In 1871, he became the executive manager for the entire RGTD administration located in Copenhagen, retiring in 1881 over growing conflict with the Danish Ministry for the Interior, to which the RGTD answered. In 1883 Rink and his wife moved to Oslo, where their daughter had settled. There Rink spent the last 10 years of his life, until his death in 1893, still fully preoccupied with his scholarly activities and writings.3

Although Rink was trained as a natural scientist and earned fame as a talented geologist, glaciologist, and a meticulous cartographer, he eventually devoted most of his scholarly efforts to studying the cultural and social situation of the Inuit.

An obvious reason for this was the position he held as a prominent colonial administrator. As a governor of South Greenland, which held two-thirds of the island’s aboriginal population, he was expected to provide solutions to the problems facing the province’s inhabitants. From the earliest days of his administrative career, Rink felt it necessary to augment and ameliorate his knowledge of the people and societies within his province. Soon his wish to know more about the habits and opinions of the people in his province developed into an academic obsession. This obsession resulted in many detailed and comprehensive studies of the material and intellectual culture of the Greenlanders that established Rink as one of the founding fathers of Eskimology.

Rink contributed to the development of Eskimology beyond the impressionistic approach practiced by most of his predecessors. His training as a natural scientist had convinced him that words combined with numbers and statistical tables were superior to words without numbers and tables. Rink’s oeuvre was characterized by an empirical approach that incorporated methodical observations such as the count, measurement, and statistical ranking of the phenomena he studied. His predecessors’ descriptions of the life and culture of the Greenlanders contained mostly personal impressions and conclusions based on a small number of empirical observations. In contrast, Rink’s publications on the society and culture of the Greenlanders contain a veritable stockpile of data, in many cases neatly organized in statistical tables (see, e.g., Rink, 1852a, 1855, 1857). Hence, Rink, when he published the second volume of his comprehensive description of the Danish colonies in West Greenland, had a good reason to include “a geographical and statistical description” as the subtitle to emphasize his new approach (Rink, 1857).

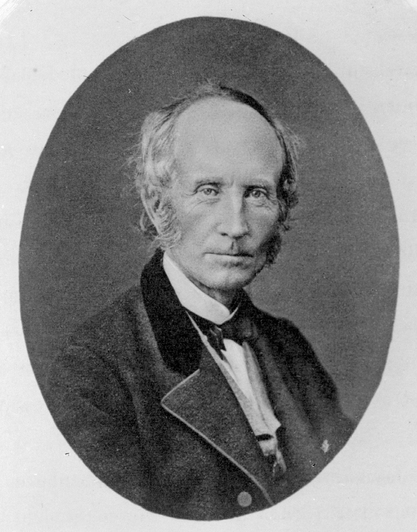

Rink’s contemporaries were impressed by his counts and tables and praised the credibility that this empirical approach gave to his research. Hence, when one of them observed that “as an author, Rink … writes so that everyone can understand him and control his credibility on all points,” he spoke for many (Fenger, 1882:103). However, despite his use of counts and tables, sometimes Rink’s studies included doubtful calculations, where the author, obsessed by his wish to present numbers and statistical tables whenever possible, tried to estimate phenomena that had not yet been counted or measured in any direct way.4 One example was Rink’s estimates of the Greenlanders’ aggregate consumption of different types of food (Rink, 1857:251–252). However, calculations based on assumption instead of proper observations constituted the exception to the rule in Rink’s oeuvre. Most of his published counts and tables were solidly based on exact data (Figure 2.2), such as those of the number of seal skins and barrels of blubber sold to the RGTD, the number of births and deaths of the Greenlanders, and other items that the Protestant missionaries and senior officers of the RGTD in different colonial districts reported on a regular basis.

Figure 2.2 Greenlanders’ family expenses for European goods calculated by Rink on the basis of the colonial trade statistics of the 1850s (from Rink 1877c:191).

These detailed and broad-scoped quantitative counts enabled Rink to be empirical in his research. As a governor of South Greenland and, later, executive manager for the RGTD, Rink had easy access to the reports that traders and missionaries sent to the governors in Greenland and their respective superiors in Copenhagen. Through these reports, Rink the colonial administrator could provide Rink the scholar with a wealth of detailed empirical data (e.g., Rink, 1857:iii).

Rink’s theory of a common cultural homeland for all Inuit tribes holds a prominent place within his achievements in the field of Eskimology. Rink was convinced that the different Eskimo (Inuit) tribes, who in the mid-nineteenth century lived separated from each other in a region spreading from Bering Strait in the west to Greenland in the east, had originally lived together in Alaska’s forest-clad inland region. He was uncertain whether the Eskimo originally came to America from Asia or whether they constituted an endogen American people. But he felt certain that all the Eskimo tribes had once lived together in Alaska’s inland, migrating from there at some unknown time. They followed the rivers down to the coast, where they developed the first traits of their distinctive marine culture. “From having been the natives of sylvan districts, they had to become a people that may be said to shun the forests, and content themselves with the most barren and ice clad shores in existence” (Rink, 1891a:3).

Rink put forward his theory of the birth of the Eskimo culture in a number of publications (Rink, 1873, 1883, 1886, 1888, 1890), culminating with his two-volume study published in 1887–1891 (Rink, 1887a, 1891a). Rink proposed that all Eskimo tribes from Siberia to Greenland used the same or similar words to designate specific hunting techniques and hunting tools, and in his eyes, this proved that the tribes had not separated until after the fundamentals of their marine culture had been developed. As additional proof, he included a comparative vocabulary that listed an assortment of words and designations common to all Eskimo groups. He further speculated that what he called the “cultural home” of the Eskimo people, the birthplace for this embryonic version of the sea-based Inuit culture, had been located somewhere on Alaska’s Arctic or perhaps subarctic coast (Rink, 1891a:5, 19).5

Settled on the shores of that country they developed their wonderful art of capturing marine animals, which culminated in their marvelous capability of facing even the most terrible experiences of the arctic climate. From Alaska they then should have emigrated, spreading gradually to the East and North over the vast regions since tenanted by them. (Rink, 1891a:1)

Since first presented to the scientific community, Rink’s theory of the Alaskan inland (riverine) origin of the early Eskimo culture has been questioned and rejected. But no one has questioned that it represented a bold and pioneering attempt to explain how and where the Inuit culture was originally born.

When Rink moved to Nuuk in 1855 to assume his new position as governor of South Greenland, West Greenland was experiencing the first forebodings of a profound social, economic, and demographic crisis. It occupied the country for the next quarter century and was later referred to as the Great Crisis (Marquardt, 1999). The southern province was hit hardest by the crisis; as governor of that province, Rink was expected to suggest proper actions that could ameliorate the deplorable state of affairs.

At the same time, the future of the North American Indians was being widely debated in the scientific literature and public circles. Rink followed this debate with great interest. He believed he could learn from the discussion about whether the American Indians should be confined to reservations where they could live in the same “tribalist” way as their forefathers or removed from the reservations and Americanized so that they could become farmers or wage laborers like other citizens of the United States (Rink, 1887b, 1891b; for the American situation, see Prucha, 1978, 1984).

When Rink set out to analyze the crisis in Greenland, he took for granted that North American Indians and Greenlanders faced similar challenges. Both were either exclusively (like the Greenlanders and some American Indian tribes) or to a great extent (those American Indian tribes who combined hunting and gathering with the cultivation of crops) hunters and gatherers. History had shown that many tribes who lived as hunters and gatherers were easily lured into self-destructive behavior by their seemingly insatiable thirst for the goods that white traders sold to them. In the American debate, whisky and the whisky-drinking Indian came to symbolize the harmful impact that excessive consumption of Western trade goods had on American Indians. In Greenland, coffee, sugar, figs, and white bread—jointly referred to as luxury goods—were considered to play a role similar to that of whisky in North America.6

Like many in the Danish Greenland administration, Rink was originally convinced that the fatal attraction of luxury goods encouraged far too many Greenlanders to sell more skins and blubber to the RGTD than their subsistence economy could support. The excessive love of coffee and other luxury goods resulted in Greenlandic households selling to RGTD traders the skins they needed for clothing and the construction of skin boats and summer tents. They also sold the blubber they needed for food and used as fuel in the soapstone lamps that provided heat and light and were used for cooking in their winter houses.

The lack of skins for boat construction in particular worsened the Greenlanders’ lifestyle. When kayaks were in short supply, new generations could no longer be trained from boyhood in the kayak hunter’s craft; this spelled doom for a society that had based its existence on hunting marine mammals (Rink, 1856:222–228, 1857:280–287, 1877b:1–3, 1877c:151–186, 192, 1882:12–18). “The Greenlanders’ economic situation, and as a consequence of this, the entire production force in Greenland, seems to be in great danger of developing into a state of decadence. The situation is such that it invites to take the most serious precautions” (Rink, 1856:223).

Some of Rink’s contemporaries, such as the former chief factor in Paamiut and Qaqortoq J. M. Mathiesen (1800–1860), argued that Greenland’s future depended on the colonial administration’s willingness to facilitate the immigration of Danes and other Europeans. The newcomers could live as fishermen (if possible, combined with some farming and stock breeding) and mine workers or practice other economic trades. Greenland could still therefore be inhabited and prosperous even if the country’s small and feeble Inuit population withered away or were swallowed up in the growing immigrant population (Mathiesen, 1852:177).

Rink did not agree. More than a hundred years of colonial history had shown that only a few immigrants from Europe could subsist in Greenland. Those who could subsist in the country benefitted indirectly from the Greenlanders’ seal hunt by delivering commercial or religious services to the seal hunters:

Evidently, there are exceptions to the common allegation that nothing can prevent nations with a level of culture similar to that of the Greenlanders from being everywhere ousted and wiped out, whenever they come into contact with civilized nations. In countries where the intruding race can utilize the natural resources to such an extent, that it produces hundred times more than the original inhabitants did, it is at least doubtful whether one shall resort to special precautions in order to preserve the latter. But in a country where a certain number of natives as well as their original trade are required to keep alive every single newcomer who wants to settle there, things are different. Here we do not speak about the preservation of a certain race or trade, but of—if I may say so—the maintenance of the indispensable economic foundation, which allows the inhabitants to survive. (Rink, 1877b:3)

Rink refused to consider the possibility of a noticeable European immigration to Greenland, claiming to be in harmony with the founding father of Danish colonialism in Greenland, missionary Hans Egede (1686–1758). Rink interpreted Egede’s message to mean that only one trade or occupation could have a long-term existence in Greenland, namely, the traditional hunt for seals and whales (Rink, 1857:384, 1865:11–15). As a secondary economic activity, fishing from kayaks and women’s boats had always played an important supplementary role in the Greenlanders’ economy. However, as Rink saw it, fishing or other nonhunting activities could not be the economic mainstay for a considerable native or immigrant population. Referring to the Qeqertarsuatsiaat district in the Southern Province (then known as Fiskenæsset, “Fisher’s Promontory”), where the RGTD had stimulated fisheries and bought fish products from the local population, Rink presented a grim illustration of what would happen if fisheries drew the Greenlanders away from the seal hunt.

We here find a striking evidence of how quickly and easily the Greenlanders through such enterprises are led away from their independent seal hunt and therefore are impoverished.… From its fisheries the population receives nothing but the most elementary provisions and, in addition to this, coffee, tobacco, bread and some thin cotton clothes. It therefore sinks deeper and deeper as regards its clothing and housing facilities and has in the last years decreased by up to eight percent every year. One must fear the worst, if means to reinstate the population’s independent trade [read: the seal hunt] cannot be found.7 (Rink, 1857:324)

For Rink, mining, sheep breeding, and European-style fisheries were activities that allowed a few people to earn an income but for a short period, until fish stocks depleted or mines emptied. In order to enable a number of people equal to the contemporary Greenlandic population (about 10,000 during his time) to subsist for a longer period, only one type of economic activity was worthy of consideration, namely, the one that had been practiced for ages by the Inuit: hunting (Rink, 1857:384–392, 1865:11–15, 1877b:1–2, 1877c:135, 166–167, 1882:1–6).8

According to Rink, the answer to the current crisis of the Greenlandic seal hunters was not in a more diversified economy of Greenland. He advocated that Denmark in Greenland should pursue a colonial policy that gave up all “foolish” ideas about the number of different economic activities that could thrive there and offer new possibilities for lucrative and less dangerous employment to future generations of Greenlanders.9 The crisis could be effectively counteracted by one thing only, namely, by adhering without faltering to the idea that everything in Greenland depended on the outcome of the native population’s seal hunt. Consequently, the country’s future prosperity depended on the colonial administration’s willingness to acknowledge this fundamental truth and to do its utmost to serve the interests of this all-important trade. If not, the consequences were grim. “Soon only a rabble of beggars and poor creatures would be left who could row a boat, perhaps fish from a kayak in fine weather etc. But who would exercise the dangerous kayak hunt which shall procure the basic necessaries and which directly as well as indirectly maintains all the rest” (Rink, 1857:384–386).

For Rink, the way to a better future for the Greenlanders was to return to a time when Westernized lifestyles and consumer habits had not corrupted the people, a time when the influence of Western civilization was restricted to converting the Greenlanders to the Christian faith. He believed future policies should be oriented toward the sale of certain useful Western commodities such as rifles, gunpowder, and metal knives and to the reduction in sales of the luxury goods presently consumed in excessive quantities.

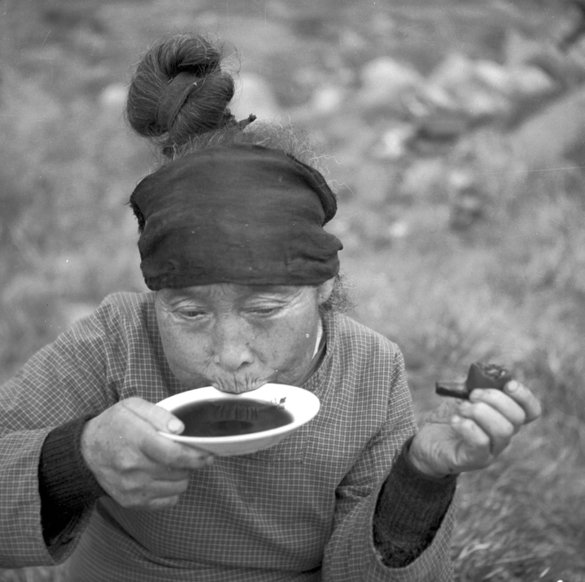

Compared to those of his contemporaries who advocated that the Danish Greenland administration should ban the sale of coffee and luxury goods to the Greenlanders, Rink was quite moderate. He understood the simple and well-deserved pleasure that a cup of coffee gave the seal hunter after a hard day’s work (Figure 2.3).10 The present Greenlandic misery was not due to the Greenlanders’ consumption of coffee, figs, and other dainties as such, but was due to their excessive consumption of these articles.

Rink was convinced that people—European as well as Greenlanders—learned from their experiences under normal economic circumstances. Under normal circumstances, a household’s excessive sale of the skins and blubber it needed for its subsistence economy would lead to poverty and starvation. This downturn would teach the household to reduce both its sale of necessaries and its purchase of unnecessary luxury goods.

However, according to Rink, the conditions were not normal in Greenland in the mid-nineteenth century. Because of the far too liberal (in Rink’s eyes) poor relief system introduced by the RGTD and the continued existence of the traditional food-sharing system, which Rink at times referred to as the “harmful communist fellowship,” starvation was not allowed to become the natural consequence of poor economic behavior.11

The continued existence of the traditional food-sharing system combined with the RGTD’s system of poor relief enabled the lazy and incompetent, who for the sake of just another cup of coffee sold the skins and blubber so badly needed for daily life, to avoid the starvation that under normal circumstances would be the price for acting self-detrimentally. In the same vein, the food sharing and the poor relief made a fool out of a diligent and rational hunter who resisted the temptations of the imported luxuries and abstained from selling more skins and blubber than his family could spare. His pay for acting rationally was not a prosperous private economy. Instead, he ended up feeding and clothing his lazy and irrational household and settlement mates, who, either because of insufficient equipment with regard to skin boats or because of lack of training in kayaking, dared not to go to sea every day to hunt for seals.

Figure 2.3 An elderly Greenlandic woman drinking coffee from a saucer (Qaqortoq, 1956). Danish Arctic Institute; image IS gjb08825c.

Rink held the firm conviction that when his province fell victim to the Great Crisis, the reason was because Denmark had adopted a colonial policy that carried harmful consequences. At first, he blamed the food-sharing and poor relief system combined with the Greenlanders’ excessive love of coffee and other luxury goods for the present misery. Starting in 1856, he grew more and more convinced that the worst of all the harmful consequences was the gradual erosion of the social order that had existed in the precolonial Greenlandic society. As Rink now saw it, the precolonial society could rely on certain cultural institutions that successfully prevented a social disorder like the present one, in which the lazy who did not hunt for seals were fed at the table of the diligent who did. In precolonial Greenland those who neglected the requirements of their personal subsistence economy were taught the lesson of starvation. Yet in the present and utterly disordered Greenlandic society, “the competent and provident” would “sooner or later be encumbered with providing for the lazy and careless. For this reason, laziness, prodigality and improvident behavior constitute a sort of crime against property rights—or at least against the rest of the society” (Rink, 1857:390–392; see also Rink, 1877c:195–196).

After 1856, Rink’s analysis of Greenland’s past and present situation placed growing importance on two precolonial social institutions: the drum song and the angakkut, or shamans.

In his article published in 1862, Rink noted that Hans Egede had “said that among the pagan Greenlanders, neither a public authority nor laws and order nor any other kind of discipline had existed. And until this day similar ideas about the Greenlanders have been more or less dominant” (Rink, 1862:89). With a few notable exceptions such as missionary Henrik C. Glahn (1738–1804) and trader L. P. Dalager (1715–1772), Rink’s predecessors in the field of Greenland studies had argued that Greenland was and always had been a society without law and order. Rink took a different stand. He fully agreed that the contemporary society was utterly disordered. Yet he now elaborated on the argument he had presented six years earlier, insisting that traditional law and order had ruled supreme in the precolonial society. The present disorder had not existed since time immemorial: Denmark’s misguided colonial policy had created it.

Led by his new political interests and priorities after 1856, Rink delved deeper and deeper into the question of how the precolonial Inuit society in Greenland had maintained a social order that successfully prevented the lazy and the incompetent from taking advantage of their diligent and competent seal-hunting compatriots. In his 1862 article, he presented a completely new theory that suggested that the current lack of social order was actually a new phenomenon, with no roots in the traditional past (Rink, 1862; Marquardt, 2009).

Rink’s theory that precolonial Greenland was a society in which law and order ruled supreme and certain social institutions, such as shamans and drum songs, ensured that the lazy members of society were duly chastised and humiliated constituted one of his most important contributions to the development of Eskimology. After quoting Hans Egede’s observation that pagan Greenlanders had lived without public authorities, law, and order, Rink continued:

But if one carefully studies what Egede’s “Perlustration” and the other historical sources tell us about the original Greenlanders, one comes to a completely different result. As regards a public authority, this evidently is to be found in the class of shamans or pagan priests. As far as we know, among some of the Indians, and among the northern tribes in particular, the secular chiefs have only a limited power whereas the greatest authority is vested in the priests, who also function as physicians. Since the Greenlanders had more to fear from nature than from hostile nations, a similar state of affairs must to an even higher degree have existed among them. Thus, in their ancient shamans secular and religious authorities were united. When it is explicitly said in the mentioned historical sources that the shamans were asked for advice in all the more important affairs of life, such as in the case of sickness, unusual death, bad hunter’s luck or similar misfortunes, and that they in addition to this were asked for advice in all matters relating to their common affairs, travels or economy—and that they were held in high esteem, were paid for their services and were obeyed, then it is unjust to say that there was no authority among them.… On the contrary, one must assume that the principal task of the pagan priests was to keep their compatriots under surveillance, so that they did not transgress the customs and conventions, which the experience of centuries had shown to be indispensable if a people should survive in such a rough part of the world. (Rink, 1862:90)

The ancient Inuit shamans did not have a military power or any other armed force at their disposal. Apart from this, Rink portrayed them as an Inuit version of the theocratic rulers known from ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. He now deeply deplored that Denmark’s Greenland administration had allowed the missionaries to combat the shamans and eventually abolish them because they were associated with paganism.12

Rink also rejected the opinion that drum songs (Figure 2.4) were nothing but a malicious and insidious way to insult a fellow citizen.13 Citing Glahn for the observation that “the Greenlanders constitute a nation which has honor as its God” (Rink, 1862:105), Rink considered the institution of the pagan drum song to have played a role similar to a public court of justice. In the drum songs, the lazy and incompetent hunters, together with all the other transgressors of public order, were ridiculed, chastised, and humiliated by the surrounding society. Rink deplored that the drum song institution, like the shamans, had been abolished because of its pagan roots.

That the Greenlanders disposed over a certain judicial court cannot … be doubted and was even admitted by the earlier missionaries.… As known, this public court was made up of the so-called dispute- or spite-songs [drum songs] which were organized when many people were assembled.… Subject for the rulings of this court could be any assumed wrong and besides that any offence against good order and custom, in particular loose morals, laziness or lacking hunter’s skills. The judicial procedure consisted in the mutual singing of satirical songs, where the accuser and the defendant sang by turns until one of them gave up. The assembly acted as the judge, and public humiliation was the punishment.… One therefore should think that such a custom, which constitutes the only public court in the country, and which additionally through its public character strengthens the conception of justice and the sense of order in society, should have been upheld [by the colonial authorities], albeit in a different form. But no, just as the public authority was abolished, so the legal procedure was completely abolished and no trace of it is today to be found in Greenland. (Rink, 1862:95–96)

Thus, the ancient pagan society had certainly “had a guarantee that the individual would not bow to his inclination to idleness, because it was a kind of law among them that everyone should be trained to hunt—and that he should be a hunter for as long as his physical strength allowed him to be so” (Rink, 1882:10). Yet Danish colonial administration, which saw only superstition and paganism instead of the preservation of the society and social order, had allowed this guarantee to be destroyed.

The social organization among hunting nations is so peculiar that this in itself explains why it is so difficult for the civilized race to understand and assess it properly. The social organization among the Greenlanders has been neglected and overlooked to about the same degree as has been the case elsewhere. Hence, if one in a few words seeks to explain why the Greenlanders have declined, the answer is that in their case one has not sufficiently adhered to the principle: “It is on laws that a nation must be built.” (Rink, 1882:7)

Figure 2.4 Drum song statue by artist Jens Kjeldsen in front of Greenland’s High Court in Nuuk. Photo by Jette Rygaard.

In one of his last works, the two-volume study of the Eskimo tribes (1887–1891), Rink explained his new findings regarding the role of the shamans and the drum songs with a formula. Moving from the west (Chukotka) to the east (Greenland), the construction of kayaks and hunting gear became more and more sophisticated, whereas the development of a social order and a clear distinction of ranks in society became less and less pronounced.

While, as before stated, a marked progress is evidently observed in passing from the Western to the Eastern tribes, as regards the kayak with its implements and the dexterity in using them, the contrary may be said so far as concerns social organization.… Several facts seem to prove that the Western Eskimo occupy a higher state of social organization than the Eastern tribes. This is manifested in the more favorable conditions for the accumulation of individual property. (Rink, 1887a:25, 28)

Admiring the well-developed system of social order among the western Eskimo (Inuit), Rink deplored the erosion of that order that had taken place in his contemporary Greenland. This erosion had turned the country into a society with a rapidly growing group of paupers and beggars.

Throughout Danish West Greenland the ancient organization of the Eskimo society began to be disturbed by European influence more than a century ago. However, the communism in living still flourishes, but without being sufficiently restricted by the original customary obligations and at the same time without being counterbalanced by a satisfactory development of the idea of individual or family-property. The natural consequence has been impoverishment. (Rink, 1887a:26–27)

Rink held it to be a matter of great importance to prove—to the scientific community in general and to those deciding the colonial policy that Denmark pursued in Greenland in particular—that the Greenlanders were fully able to pay the necessary respect to the doctrines of social order and to the rule of law. In contrast to the opinion of his many colleagues in the Greenland administration and to his earlier position until 1856 (see, e.g., Rink, 1855:190), he now argued that the crisis was not the result of some mysterious innate disposition in the character of the Greenlanders that caused far too many of them to choose the life of lazy beggars. History proved that the Greenlanders were once able to live differently. It was the legacy of the ancestors that once upon a time the Greenlandic society had been a society in which the chastisement and humiliation inflicted upon those who did not contribute to the community ensured that only the old and the disabled did not live as diligent and competent seal hunters (Rink, 1862, 1877c, 1882).

Having retired from his long service in the Danish administration of Greenland, Rink in 1882 summed up his assessment of the policies pursued by his former employer:

It is not in the way in which the trade has increased its sale of commodities, nor in the way in which the mission has performed its distinct task that one shall look for the reason why the Greenlanders have declined. The reason for this is to be found in the fact that the Europeans right from the very start have disregarded the natives’ social affairs—and this goes for their customs and conventions, which were equal in importance to laws, as well as for their patriarchal authority, which was equal in importance to a government. Even among these peaceful people, living in small and humble communities, law and government could not be disregarded without harmful consequences.… The more the tight strings, which right from childhood kept everyone to his vocation were loosened, the more the inclination to seek the pleasures of the moment gained the upper hand. One cannot be surprised that as the respect for old conventions and customs was disregarded, it was carelessness and folly, which came … to play master.… In this way, we can see how the position of the able hunter has grown ever more troublesome. (Rink, 1882:89)

The above words constitute a kind of swan song for Rink as a prominent Greenland administrator. He still “hoped for a better future, if serious changes should be introduced.” But he was far from certain, and if the necessary changes were not made, “courage will sink deeper down, the sea will call for more victims, physical weakness will spread and it is to be feared that incidents of illness will be more mortal than before” (Rink, 1882:89–90).

When assessing Rink’s role in the development of Eskimology, it is imperative to note that he was a leading member of a small group of colonial administrators who in 1856 submitted a proposal to the Danish government on how the crisis in Greenland could be effectively counteracted (Rink, 1856:181–193). In that proposal Rink and his associates argued that the moral behavior of the Greenlanders was decaying rapidly. More and more Greenlanders were both unable and unwilling to exercise a seal hunter’s dangerous trade. Instead of providing for themselves as their ancestors had done, they took to begging for food and support from the colonial administration and from their ever-fewer seal-hunting compatriots.

Rink knew that a possible argument against the adoption of his proposal was the widespread opinion that the Greenlanders were unable to behave in a way different from that which had brought about the ongoing crisis. A common argument among Rink’s contemporaries was that the Greenlanders were the “children of Nature,” who lacked the natural endowment for demonstrating the discipline and diligence that characterized the civilized Europeans. Because of this, they were unable to harmonize their lifestyles with European standards for economic rationality and providence. To believe otherwise was to believe that a leopard could do away with its spots.

Rink lived in the age of national romanticism. A prominent element in the ideology of national romanticism was the assumption that through the study of a nation’s history one could learn what its national spirit (Volksgeist) enabled a given nation to be—and not to be. Another side of the same ideology was that a nation’s past deeds heralded the deeds one could expect from it in the future.

With an intellectual and public background of this kind, one can understand why Rink invested so much scholarly energy in his search for proof that the Greenlanders before colonialism had lived as provident and diligent seal hunters and that they therefore could come to live like this once again. He was inspired by his re-reading of the works of the eighteenth-century missionaries and traders, as well as by the messages he distilled from the Greenlanders’ myths and folktales (Rink, 1862:99). On that basis, Rink repeatedly insisted that in the precolonial times the shamans and the drum songs had prevented a situation like the present one, in which moral decay was allowed to spread among the Greenlanders.

The social fabric is a fragile texture, and if you take something out, you must put in something else. Otherwise, everything starts to disintegrate. When Denmark’s colonial administration allowed for the shamans and the drum songs to be abolished, it forgot to put in that something else.

Consequently, new social and cultural institutions that could censure lazy beggars and those who, for the short-lived pleasure of another cup of coffee, sold all the skins and blubber needed for their families’ existence were urgently needed. The proposal submitted by Rink and his associates in 1856 advocated for the establishment of a new institution, the so-called Board of Guardians. For the contemporary crisis-ridden society, this board was supposed to do what the drum songs and shamans had done for the society in precolonial time (Rink, 1862:109–110).

After an introductory period starting in 1857, the Board of Guardians was indeed introduced in 1863 as a nationwide institution in Greenland. Each of the 13 colonies in West Greenland was to have its local Board of Guardians that included elected Greenlandic members (who were elected by and from local hunters who did not receive poor relief) and European ex officio members, such as chief factors, deputy factors, and missionaries. The boards exercised a limited self-rule in their respective districts. They administered poor relief and offered special bonuses (known as the repartition) to the most efficient hunters. The boards answered to the governors and to Denmark’s minister for interior affairs. Later in his career, Rink proposed that the Board of Guardians be supplemented by a permanent Greenland Commission in Denmark. This commission would advise the minister for interior affairs and the RGTD and also prepare plans and ideas that could ameliorate the situation in Greenland. The commission could also advise the Boards of Guardians in Greenland in financial matters (see Rink, 1877b:16–23).

Like the national romanticists, Rink believed that history tells us what we have been, and thus, also what we can come to be again. To avoid criticism for advocating something utterly impossible, namely, that the Greenlanders could behave differently from how they behaved in the mid-nineteenth century, Rink felt it imperative to prove that at one time, certain social institutions had forced Greenlanders to hold diligence and providence in high esteem, thereby encouraging proper behavior. If the colonial administration were willing to be enlightened by Rink’s scholarly works, social order and responsible behavior could be reinstated in Denmark’s colonial empire on the banks of the Davis Strait. The only thing needed to bring about that happy state of affairs was for the government in Copenhagen to authorize the establishment of a new Board of Guardians in Greenland. Such boards could then take up the torch that the shamans and drum songs had been forced to put down a good century ago.

Hence, Rink’s effort starting in 1858 to organize and publish a collection of Greenlandic myths and folktales (Rink, 1866, 1871, 1875) should be viewed in a different perspective.14 Rink’s aim was not merely to serve the interests of literary and intellectual history. Through the collection of the Greenlanders’ ancestral myths and folktales, Rink hoped to find manifestations of the very social and moral values that they had originally held in high esteem. His hope was that these myths and folktales could prove that social order and respect for the piniartorsuaq (the great hunter) were not foreign to the Inuit way of organizing society. As Rink saw it, his hope was fulfilled (Rink, 1862:99).

When the Greenlanders cannot do without their myths, this is because these myths constitute their Poetry, and in particular, because they include what one might call their Heroic Poetry.… First and foremost, it is of course the great kayakers or hunters of the past who are portrayed, those men who in Greenlandic are called Saperfêratat, that is “those who can cope with everything.” For today’s hunters there is only little honour to be gained. In former times, when intra-coastal traffic was tense, their doings were eulogized in what in a Greenlandic context constitute great assemblies. Today such great assemblies have ceased to exist, and the eulogy of the hunt has retired to the small communities in the winter houses. Here the sound of the eulogy can still be heard in the long evenings from the mouth of the storyteller. And we may assume that it still is instrumental in awakening and strengthening the youth for the exercise of the deed which now as before has to maintain this small isolated society. (Rink, 1877a:30)

In his capacity as a governor, Rink recommended to the Danish government the proposal for the establishment of the Board of Guardians that he himself had coauthored. In his letter of recommendation, Rink wrote, “One says that [the Greenlanders] are careless, improvident etc., and gives to this disposition the blame for all misery. No doubt about it, they are careless—but it would be unfortunate if this is the only thing to be said about this matter.” He continued by suggesting that prior to colonization, the carelessness and improvidence of the Greenlanders had been counteracted by “certain customs and conventions” (Rink, 1856:235). But no one knew exactly what the nature of these customs and conventions was.

As concerns the Greenlanders’ own original social organization, one has never considered it to be important—nor has one investigated whether they had laws or conventions which it would be desirable to uphold and develop further. For that reason, I hold it to be proper to investigate a little further this curious cross between a lawless and anarchic and—if I am allowed to say so—a patriarchal and idyllic social organization. (Rink, 1856:233)

In his 1856 letter of recommendation, Rink invited scholars to demonstrate which customs and conventions upheld the precolonial society in Greenland as an orderly and well-functioning social body. He repeated this invitation again in the following year (Rink, 1857:389). In 1862, in his article on why Greenlanders and other hunter-gatherers experienced a decrease in their material well-being when they came into close contact with the Europeans, Rink gave his answer to the question he had posed to the scientific community six years earlier. The answer that he developed in the course of his service as a scholar and an administrator was that the shamans and the drum song institution had prevented the Greenlandic society from falling into the abyss of moral decay. The old folks knew how to discipline the lazy and improvident—and how to elevate the diligent and provident.

The law-abiding and orderly society of the ancestors, a topic so diligently studied by Rink in his pioneering books and articles, could not be reduced to a useful fiction invented by Rink the scholar to serve the political purposes of Rink the colonial administrator. When he recommended the proposal to the minister of the interior, he was well aware that its basic idea, namely, that contemporary Greenlanders would bow respectfully to a new public authority (the board), was not in harmony with what many then believed and what he himself had previously said about this matter. He therefore assured the minister that his change of mind was the result of his own scientific research (Rink, 1856:222–223).

Rink’s Eskimology ties together political administration and science in a dialectical relation. His years of active service in the Danish Greenland administration coincided with the period known as the Great Crisis in West Greenland. Many of his publications dealt with the different manifestations of this crisis and how they should be interpreted scientifically and counteracted practically. Only rarely (one such example was his glaciological reports) did Rink produce what may be called pure science. His pioneering studies in the field of Eskimology were all examples of practical science, or “applied anthropology” as Nellemann (1967) once called it, that is, knowledge produced with the purpose of enlightening action.

Rink believed that his new findings represented the truth about how social order and public authority had once been an integral part of the Greenlandic society. However, his strong political interest in proving that Greenlanders could learn to prioritize the interests of tomorrow above the idle pleasures of the moment and that they could learn to bow willingly to the stern instructions of a public authority like the Board of Guardians gives a certain bias to this part of his scientific oeuvre. In particular, I suspect that his interpretation of the social role of the ancient shamans, which he portrayed as theocratic rulers similar to the priest-kings known from ancient history, was flawed by exaggeration (Rink, 1862:88–97).

How public authority was exercised in precolonial Greenlandic society, a society that Robert Petersen (1993) has called a society without chiefs, is an elusive topic.15 However, when reading today what Rink said about this matter since 1856, one must keep in mind that the scientific findings of Rink the scholar were answers to questions posed by Rink the administrator. Historical studies have always been a toolbox in which one can look for solutions from the past that can inspire the people of the present. That certainly was the case when Hinrich Rink presented his theory on the role played by the shamans and the drum songs in ancient, precolonial Greenland.

1. Throughout this paper, all quotations from Rink’s Danish publications are translated into English by the author.

2. Denmark’s colonial empire in mid-nineteenth century Greenland was referred to as Danish West Greenland. Danish West Greenland comprised 13 (after 1866, 12) separate colonies. For administrative purposes, it was divided into two provinces, the Northern Province (with seven colonies) and the Southern Province (with six colonies; five colonies after 1866). The borderline between the two provinces was close to the Arctic Circle.

3. For further biographical details on Rink, see Steenstrup (1894), Oldendow (1955), Gad (1982), Høiris (1986), and Marquardt (2009).

4. It should be mentioned that Rink gave credit to Samuel Kleinschmidt (see Sadock, this volume) for having helped him “with all statistical calculations relating to the Greenlanders’ life and situation” in the preface to his topographical description of South Greenland (Rink, 1857:iv).

5. Rink never excluded the idea that the cultural home of the Eskimo (Inuit) might have been located somewhere on Alaska’s more southern and temperate coast or perhaps in the Davis Strait region or even in Asia. Yet he considered it far more probable that its location had been somewhere on Alaska’s Arctic or subarctic coast (Rink, 1891a:3–6, 22).

6. Until 1950, it was forbidden to sell alcoholic beverages to the Greenlanders. Sources show that the RGTD’s prohibition policy was occasionally undermined by illegal and clandestine trade, but overall, the prohibition policy ensured that alcoholism was almost nonexistent among the Greenlanders during the colonial era from 1721 to 1950/1953.

7. Rink disliked fisheries, where the Greenlanders provided the labor force and the Europeans supplied the gear and wages. In a rather biased interpretation of the consequences of an experiment with such fisheries, tried between 1833 and 1841, Rink concluded that “since it of course was out of the question to pay wages to a European crew … Greenlanders were used instead. And it soon showed that they, as they through promises of a higher pay in the fishing season were allured to gather at the fishing station and were drawn away from the independent seal hunt, could not sustain from the fisheries. In short, the enterprise which had originally begun its existence with big words ended up with starvation, people clad in rags and bankruptcy” (Rink, 1857:231–232).

8. Ironically, when Rink warned against the dismal consequences if Greenlanders were to seek employment outside the seal hunt, he also strove to increase the number of Greenlanders employed on a permanent basis by the RGTD. In particular, Rink tried to increase the number of Greenlanders in middle-ranking positions (primarily as outpost managers; see Rink, 1882:18–26, 65–87).

9. Rink was fully aware that the seal hunt, in particular the hunt from kayaks in open water, was a dangerous occupation. He compared the seal hunt to military conscription in European countries (Rink, 1882:14).

10. Although the majority of Rink’s contemporaries in the RGTD and Christian missions considered coffee to be the main culprit among the harmful luxury goods, Rink, who originally shared this opinion, gradually came to have a more positive opinion about its consumption (see, e.g., Rink, 1855:60). In Rink’s opinion, the consumption of white bread was more to blame for the present wretched state of affairs in Greenland. In his later writings, he argued that the best way to avoid continued excessive consumption of luxury goods was not to prohibit the sale of these items but to explain to the Greenlanders that it was in their own best interest to reduce the consumption of coffee, white bread, etc. Referring to the European and Greenlandic employees of the RGTD and the mission, who were allowed to buy coffee, Rink concluded that it would be a mistake to restrict the sale of luxuries to the common Greenlanders. “A civilization which does not allow its people to buy for their money what the Europeans and those of their compatriots who work for the Europeans are allowed to buy, can hardly be called an improvement” (Rink, 1877b:8).

11. The RGTD’s poor relief system was a combination of two things: general poor relief (sultekost, or “food for the starving”), in which provisions were given free to needy people, and a possibility for hunters to buy on credit in the RGTD stores.

12. As a prominent employee of the state with Lutheran Protestantism as its official religion, Rink never said in plain words that it had been a mistake to combat elements of paganism such as the shamans and the drum songs. Instead, he criticized the colonial administration for having abolished two institutions that guaranteed the social order without providing substitute institutions or rules. As he said in 1862, “That the shamans had to be done away with is obvious. Pagan superstition cannot co-exist with Christianity. But is it acceptable to do away with the public authority at the same time?” (Rink, 1862:92).

13. Drum songs are song duels.—Ed.

14. See Thisted (1994, 2001) on Rink’s collection of Greenlandic myth and folktales.

15. Petersen (1993:130) is convinced that “Rink’s idea that the shamans [in Greenland] possessed a power close to that of a chief is unsubstantiated.”

Fenger, Hans Mathias. 1882. Opinion piece. Nationaltidende, July 3, 1882. [Reprinted in Hugo Hørring, Bemærkninger til Justitsraad, Dr.Phil. H. Rinks Skrift: Om Grønlænderne m.m., pp. 101–110. Copenhagen: Gad, 1882.]

Gad, Finn. 1982. “Hinrich Johannes Rink.” In Dansk biografisk Leksikon, vol. 12, pp. 244–246. Copenhagen: Gyldendal.

Høiris, Ole. 1986. Antropologien i Danmark. Museal etnografi og etnologi. Copenhagen: Nationalmuseet.

Marquardt, Ole. 1999. A critique of the common interpretation of the great socio-economic crisis in Greenland 1850–1880: The case of Nuuk and Qeqeertarsuatsiaat. Études Inuit Studies, 23(1–2):9–34.

———. 2009. “H.J. Rink.” In Grønland: En refleksiv udfordring; Mission, kolonisation og udforskning, ed. O. Høiris, pp. 129–154. Aarhus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag.

Mathiesen, Jens Mathias. 1852. Om Grønland, dets Indbyggere, Producter og Handel. Copenhagen: Hagerup. [Reprint, J. Berglund and N. B. Josephsen, eds. Nuuk: Greenland National Museum and Archives, 1990.]

Nellemann, George. 1967. Applied Anthropology in Greenland in the 1860’s: H.J. Rink’s Administration and View of Culture. Folk, 8/9:221–241.

Oldendow, Knud. 1955. Grønlændervennen Hinrich Rink: Videnskabsmand, skribent og Grønlands-administrator. Copenhagen: Grønlandske Selskab.

Petersen, Robert. 1993. “Samfund uden overhoveder—og dem med: Hvordan det traditionelle grønlandske samfund fungerede og hvordan det bl.a. påvirker fremtiden.” In Grønlandsk kultur- & samfundsforskning 1993, pp. 121–138. Nuuk, Greenland: Ilisimatusarfik/Atuakkiorfik.

Prucha, Francis Paul. 1978. Americanizing the American Indians: Writings of the “Friends of the Indian,” 1880–1900. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

———. 1984. The Great Father: The United States Government and the American Indians. Volumes 1–2. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Rink, Hinrich Johannes. 1847a. Die Nikobarischen Inseln: Eine geographische Skizze mit spezieller Berücksichtigung der Geognosie. Copenhagen: Klein.

———. 1847b. Erindringer fra mit andet Ophold paa de nikobariske Øer. Dansk Tidsskrift, 1(1):131–169.

———. 1852a. De danske Handelsdistrikter i Nordgrønland, deres geographiske Beskaffenhed og produktive Erhvervskilder. Første Deel. Copenhagen: A. F. Høst.

———. 1852b. Om Monopolhandelen paa Grønland. Betænkning i Anledning af Spørgsmaalet om Privates Adgang til Grønland. Copenhagen: A. F. Høst.

———. 1855. De danske Handelsdistrikter i Nordgrønland, deres geographiske Beskaffenhed og produktive Erhvervskilder. Andel Deel. Copenhagen: A. F. Høst.

———. 1856. Samling af Betænkninger og Forslag vedkommende den Kongelige Grønlandske Handel, udgivne paa Indenrigsministeriets Bekostning. Copenhagen: Klein.

———. 1857. Grønland geographisk og statistisk beskrevet: Det søndre Inspektorat. Copenhagen: A. F. Høst

———. 1862. Om Aarsagen til Grønlændernes og lignende, af Jagt levende Nationers materielle Tilbagegang ved Berøringen med Europæerne [The reason for the material decline of the Greenlanders and similar peoples living by hunting after contact with the Europeans].

Dansk Maanedsskrift, 2:85–110. [English translation published in G. Nellemann, 1967, Folk, 8/9:221–241.]

———. 1865. Bemærkninger angaaende den Betænkning af 23de Juli 1863, som er afgivet af den til Overvejelse af den grønlandske Handels Forhold nedsatte Commission, og navnlig angaaende Sydgrønland, samt Forslaget om et Forsøg paa Frihandel. Copenhagen: Klein.

———. 1866. Eskimoiske Eventyr og Sagn: Oversatte efter de indfødte Fortælleres Opskrifter og Meddelelser af H. Rink. Copenhagen: C. A. Reitzel.

———. 1871. Eskimoiske Eventyr og Sagn. Supplement. Copenhagen: C. A. Reitzel.

———. 1873. On the Descent of the Eskimo. Journal of Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 2(1):104–108.

———. 1875. Tales and Traditions of the Eskimo, with a Sketch of Their Habits, Religion, Language and Other Peculiarities. Edinburgh: W. Blackwood and Sons.

———. 1877a. Nogle Bemærkninger om de nuværende Grønlænderes Tilstand. Geografisk Tidsskrift, 1:25–30.

———. 1877b. Om en nødvendig Foranstaltning til Bevarelse af Grønland som et dansk Biland. Copenhagen.

———. 1877c. Danish Greenland: Its People and Products. London: H. S. King.

———. 1882. Om Grønlænderne, deres Fremtid og de til deres Bedste sigtende Foranstaltninger. Copenhagen: A. F. Høst.

———. 1883. “Les dialects de la langue esquimaude, éclaircis par un tableau synoptique de mots arranges d’après le système du dictionnaire groenlandais.” In Congrès International des Américanistes: Compte rendu de la Cinquième session, pp. 328–337. Copenhagen.

———. 1886. The Eskimo Dialects as Serving to Determine the Relationship between the Eskimo Tribes. Journal of Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 15(2):239–245.

———. 1887a. The Eskimo Tribes: Their Distribution and Characteristics, Especially in Regard to Language. With a Comparative Vocabulary and a Sketch-Map. Meddelelser om Grønland, 11.

———. 1887b. Om Resultaterne af de nyeste etnografiske Undersøgelser i Nordamerika. Geografisk Tidsskrift, 9:118–131.

———. 1888. The Migrations of the Eskimo Indicated by Their Progress in Completing the Kayak Implements. Journal of Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 17(1):68–74.

———. 1890. On a Safe Conclusion Concerning the Origin of the Eskimo, Which Can Be Drawn from the Designation of Certain Objects in Their Language. Journal of Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 19(4):452–458.

———. 1891a. The Eskimo Tribes: Their Distribution and Characteristics, Especially in Regard to Language. With a Comparative Vocabulary. Supplement or Volume II. Meddelelser om Grønland, 11.

———. 1891b. Om Resultaterne af de nyeste etnografiske Undersøgelser i Amerika. Geografisk Tidsskrift, 11:202–209.

Steenstrup, Knud Johannes Vogelius. 1894. Dr. Phil. Hinrich Johannes Rink. Geografisk Tidsskrift, 12:162–166.

Thisted, Kirsten. 1994. Som perler på en snor. Fortællestrukturer i grønlandsk fortælletradition—med særligt henblik på forskellen mellem de originale og de udgivne versioner. Ph.D. diss., Ilisimatursarfik/University of Greenland, Nuuk.

———. 2001. “The Impact of Writing on Stories Collected from Nineteenth-Century Inuit Traditions.” In Inclinate Aurem: Oral Perspectives on Early European Verbal Culture: A Symposium, ed. J. Helldén, M. Skafte Jensen, and T. Pettitt, pp. 167–210. Odense, Denmark: Syddansk Universitetsforlag.