Only Denmark has institutionalized Eskimology as a university discipline. Today, Eskimology and Arctic studies is a multifaceted discipline within the Faculty of the Humanities at the University of Copenhagen (Figure 10.1). This discipline deals with language, culture, history, and society in the Inuit Arctic region, with a particular emphasis on Greenland, and in many respects, it is considered an area study.

During the nineteenth century, Danish engagement in scientific research in Greenland intensified significantly, partly because of a state policy that increased Danish control of the colony and partly as a result of the development of modern academic disciplines. Geological and geographic research in Greenland was a major interest of the Danish state, so in 1878 the Danish government created the Commission for Geological Investigations in Greenland. The commission immediately launched a broadly focused scientific periodical called Meddelelser om Grønland (Monographs on Greenland), the first regular and still-published journal of Arctic studies (Thuesen, 2005b:585). This commission, later known as the Commission for Scientific Investigations in Greenland, gradually broadened its focus to embrace all disciplines, including in this case archaeology, ethnology, and linguistics.

Inspector of South Greenland and, later, director of the Royal Greenland Trade Company Hinrich J. Rink (see Marquardt, this volume) was an important figure behind these new research initiatives. He himself contributed several works of lasting significance to the field of studies later termed “Eskimology.”

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, state interests of sovereignty played an important role in directing the research initiatives in Greenland, as East Greenland was colonized in 1894 and a permanent Danish presence was established in Thule in Northwest Greenland in 1910. Danish sovereignty over the entire territory of Greenland was finally established by the verdict of the international court in The Hague in 1933. One publication of special importance to Eskimology is naval officer Gustav F. Holm’s Ethnological Sketch of the Angmagssalik Eskimo, originally published in Danish in Meddelelser om Grønland (Holm, 1888). Holm’s monograph represents, together with Franz Boas’s The Central Eskimo (Boas, 1888) from the same year, the starting point of scientific ethnographic studies in the Arctic (Thuesen, 2005b).

Figure 10.1 Historic warehouses in downtown Copenhagen formerly belonging to the Royal Greenland Trade Company are currently hosting a number of Arctic, Greenlandic, and North Atlantic institutions, including the Department of Eskimology and Arctic Studies of the University of Copenhagen. Photo by Justyn Salamon, 2012. Copyright: Nordoskop.

The creation of Danish Eskimology in the beginning of the twentieth century can be seen as the institutionalization of a specific academic field, which was founded through a long tradition of knowledge production initiated by Danish colonial state authorities from the early colonization of Greenland in the eighteenth century. This essay will examine why and how the early efforts in Greenland and Eskimo research were turned into a university discipline in Denmark. It addresses the formation, development, and impact of the discipline of Eskimology at the institutional level through the lens of the research and activities of Professors William Thalbitzer, Erik Holtved, and Robert Petersen and how the discipline positioned itself through the shifts in the Danish-Greenlandic political relations of the twentieth century, from classical colonialism to postwar modernization and decolonization policies until Greenlandic Home Rule in 1979. Such discussion is particularly important because the history of research concerning the discipline of Danish Eskimology has to deal with the precondition that this discipline has been a part of, and a tool for, colonialism as well as an agent of decolonization. Danish Eskimology can serve as an example of how the research agenda of Arctic social scientists has been influenced by the dilemma of being loyal to the colonized or formerly colonized society studied while remaining a part of the Western dominant or colonizing society. I shall also focus on certain conditions in the development of the Danish university institution in the twentieth century that explain why Denmark is the only country to turn Arctic or Eskimo research into a formal university discipline.

A high degree of continuity existed among the three professors of Eskimology that has affected the consolidation of the discipline. William Thalbitzer was appointed in 1920 and retired in 1945. He was succeeded by his student Erik Holtved, who retired in 1968. Robert Petersen, a student of Holtved, was appointed in 1975 and returned to Greenland in 1983 to become the first rector of Ilisimatusarfik/University of Greenland. However, William Thalbitzer was a founder of the discipline, and I shall devote considerable attention to the presentation and discussion of his contributions to Eskimology. He had the advantage of being the single staff member of the discipline in its early years, so Eskimology could be seen, at least in its founding years, as his personal project. Although it is important to review Thalbitzer’s research and methods in detail, he did not work alone. He was part of a large international academic multidisciplinary network that contributed to the overall rise of the discipline.

This essay is based on several smaller articles on the history of Eskimology written mostly by Danish Eskimologists (see the acknowledgments section). A few studies on the history of Danish Eskimology should be credited in particular, namely, Robert Petersen’s article in the 500-year-anniversary publication of the University of Copenhagen (Petersen, 1979), Inge Kleivan’s article in the journal Inter-Nord (Kleivan, 1987), and several articles in Grønlandsforskning, a collection on the history of Greenlandic research (Thisted, 2005). I also had access to unpublished materials written by Thalbitzer that are located in the Polar Library and the archives of the Eskimology and Arctic Studies Section at the University of Copenhagen.

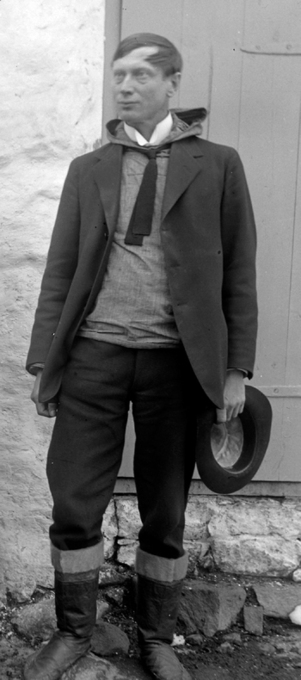

Thalbitzer studied Scandinavian philology and English at the University of Copenhagen and graduated in 1899 (Figure 10.2). Among his main teachers was the famous linguist and phonologist Otto Jespersen. Thalbitzer was encouraged to give up his childhood dream of going to Brazil to study South American Indians by physical anthropologist Søren Hansen. According to one of Thalbitzer’s students, Hansen told Thalbitzer to go to Greenland instead because “the study of Eskimo language and vernacular poetry is almost untouched ground” (Hammerich, 1959:2).

During the first decade of the twentieth century, Thalbitzer went on two longer stays in the northern part of West Greenland and in East Greenland and did field research on the local language and culture. The results of his work were presented in a number of internationally renowned publications (e.g., Thalbitzer, 1904, 1911, 1914–1941).1

In 1920, Thalbitzer was appointed a professor, or so-called docent, in “Greenlandic (Eskimo) language and culture,” a position that was turned into a professor chair in 1926 (Petersen, 1979:180). One reason that a position was opened for him at the University of Copenhagen was his well-known conflict with the Ethnographic Department at the Danish National Museum over access to the Greenlandic collections. Thalbitzer’s personal disagreement with Thomas Thomsen, curator and, later, head of the Ethnographic Department in the years prior to Thalbitzer’s tenure at the university, made him keep an almost lifelong distance from the museum’s ethnographers and archaeologists (Thalbitzer, 1917; Høiris, 1986:259–261; Thuesen, 2005a:255, 2005b:586). Indeed, he did not personally enter the museum between 1910 and 1956 (Hammerich, 1959:4). However, Thalbitzer was very social in other settings. He was an engaged Danish representative in the International Congress of Americanists, and he personally attended most of the congress meetings between 1904 and 1956 (Hammerich, 1959:5). His huge body of correspondence over the years, now kept at the archives of the Danish Royal Library, reveals a large network of colleagues and friends both internationally and in Greenland. He not only was in contact with people like Franz Boas, Marcel Mauss, and Lucien Lévy-Bruhl but also kept in close contact with many Greenlanders and people who helped him with his projects, including Henrik Lund, Johan Petersen, and Jonathan Petersen.

Figure 10.2 William Thalbitzer in South Greenland, 1914. Danish Arctic Institute, Copenhagen.

The meeting between Thalbitzer and sociologist Marcel Mauss in Paris in 1905 seems to have been important to both men. Thalbitzer’s linguistic research was widely quoted in Mauss’s seminal essay on the seasonal variations of the Eskimo (Mauss, [1904–1905] 1979), and Mauss helped Thalbitzer construct a questionnaire for his fieldwork in East Greenland. Thalbitzer’s use of the new French sociological methods and theoretical ideas on the role of intuition in scientific work was met with resistance in Denmark, especially at the National Museum (Gulløv, 1995:255).

When Thalbitzer received his position at the University of Copenhagen, the term “Eskimology” did not exist; instead, during the 1920s Thalbitzer used the term “Eskimo research” or “Eskimo philology.”2 He introduced the term Eskimology for the first time in his unpublished lecture notes from 1937–1938 (Thalbitzer, 1937–1938:20), which included a definition (my translation from Danish):

Eskimology as science can then in principle set up a plurality, a sequence of tasks, for example:

• Typology

• Ecology

• Interpretation of the language

• Representation of the products of intellectual culture3 (“literature”—folklore—“music”—“art” and so on)

• Sociology

• Folk history (for example legends …) and ethnology

• Psychology (mentality)

Maybe it is exactly this, which is most valuable for Eskimology as science.

A few years later, in 1940, Thalbitzer first used the term Eskimology in print in the obituary he wrote for Gustav F. Holm (1849–1940), the pioneer scholar of East Greenlanders:

The Eskimos soon became one of the best known primitive people [naturfolk] in the world, thanks to G. Holm’s establishment of the Danish ethnological school, which deals with the Greenlanders, the Inuit people, “Eskimology.” (Thalbitzer, 1940:22; my translation)

Thalbitzer did not explicitly mention his comparative approach or history in his definition of Eskimology, but as noted by anthropologist Ole Høiris, Thalbitzer was the first in Denmark to formulate anthropology as a historical project through engaging in the discussion, raised by Hans P. Steensby, about the origin of the Eskimos (Høiris, 2009:233–234; Gulløv, this volume).

Thalbitzer was for many years the single staff member in his discipline at the University of Copenhagen and was in many ways a loner with a strong personality, who took often controversial viewpoints in both the Greenlandic and Danish press. He was at times very critical of the colonial administration of Greenland and ran into trouble with the mission authorities during his stay in Ammassalik because he openly encouraged polygamy among the Greenlanders (Hammerich, 1959:3). As early as in 1908, he had spoken of “Eskimo nationality” in a public speech, and in another speech in 1931 to Danish national politicians, he pointed to “the awakening and conscious national sentiments/feelings” among Greenlanders (Kleivan, 1995:6). Remarkably, Thalbitzer recognized the Greenlanders as a people and a nation in a newspaper interview in 1956, at a time when Greenland was subject to integration into the Danish Realm (Kleivan, 1995:6). It took more than 50 years before Denmark officially recognized the Greenlanders as a people in the Self Rule Act of 2009.

Besides Erik Holtved, Thalbitzer had only two other students, Svend Frederiksen (1906–1967), who later became a professor in the United States, and Louis L. Hammerich (1892–1975), who was a professor of German philology at the University of Copenhagen.4 Hammerich was genuinely interested in Eskimo linguistics, and because of the developments in Nazi Germany and difficulties of working in German studies in the late 1930s, he considered changing his field of research from German to Eskimology but eventually managed to contribute to both disciplines (Hammerich, 1982:90). Hammerich published a number of Eskimo language studies, many based on his fieldwork in Alaska in the 1950s.5

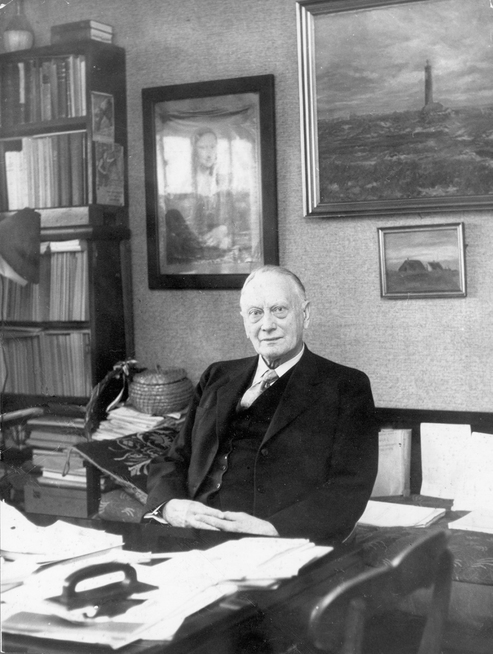

When Thalbitzer retired (Figure 10.3), he revealed some of his unfulfilled visions for Eskimology and for the education of Greenlanders in the magazine Kalâtdlit that was published by the Association of Greenlanders in Copenhagen in both Greenlandic and Danish:

Figure 10.3 William Thalbitzer in his home, 1958. Unknown photographer. Photo courtesy Department of Eskimology and Arctic Studies, University of Copenhagen.

Unfortunately, no Greenlanders have ever visited my lectures; such pleasure should not fall into my lot. But I hope, that in the future the young Greenlandic men or women that come to Denmark to educate their skills, shall not forget that the University of Copenhagen in the larger world is highly recognized.… Danish science is of as fine a quality as Danish bacon and Danish butter. (Thalbitzer, 1943:5; my translation)

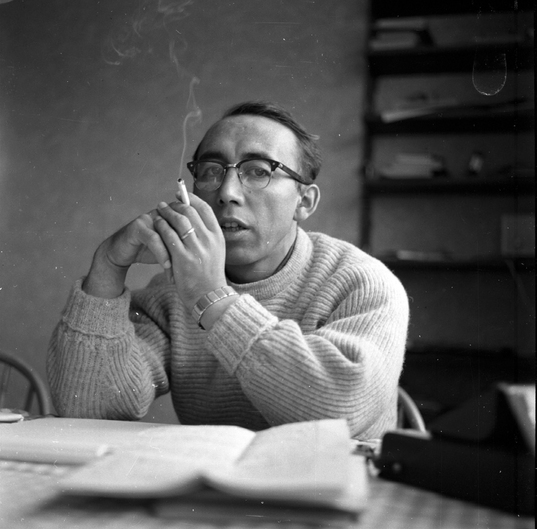

Erik Holtved succeeded Thalbitzer in 1945 (Figure 10.4). At this time, the chair was still called “Greenlandic (Eskimo) language and culture” (Petersen, 1979:185; 1995:60–61). In 1951 the position was turned into an ordinary professorship in “Eskimo language and culture” following a suggestion from Holtved to the university. His argument was mainly that “the discipline necessarily must cover the entire Eskimo area as its field of research, in order to be able to elucidate the special cultural development in Greenland and, accordingly, cover Eskimo Science as a whole” (quoted in Skyum-Nielsen, 1952:193). He also argued that the international development in Eskimo studies was “moving westwards” and opening new collaborations with the North American researchers (Skyum-Nielsen, 1952:193). Holtved was most probably referring to the Arctic Institute of North America established at McGill University in Montreal in 1944.

Erik Holtved worked as a painter for several years before he entered the world of academia and Arctic studies. He wrote to the Danish National Museum in 1930 asking to join an expedition to Greenland. He described himself as “a younger painter, especially illustrator and handyman” and added as his reason for applying “a strong wanderlust and drive towards the great and lonely nature” (quoted in Nellemann, 1995:12; my translation from Danish). In 1931, he was accepted as an assistant on Knud Rasmussen’s Sixth Thule Expedition to Southeast Greenland, where he participated in archaeological excavations at Lindenow Fjord. During the following years from 1932 to 1934, he participated in Norse and Eskimo archaeological surveys in Southwest Greenland, Disko Bay, and the Qaqortoq (Julianehåb) district (Nellemann, 1995:12). At this time, with the encouragement of Knud Rasmussen, he enrolled at the University of Copenhagen and became a student of William Thalbitzer. Holtved spent the years of 1935–1937 in Thule as an archaeologist during the summer and as an ethnographer and linguist during the wintertime (Nellemann, 1995:12). After his return, he was employed as an assistant and, later, curator at the Ethnographic Department at the National Museum in Copenhagen. He graduated in 1941, published his archaeological results from Thule in 1944 as a doctoral dissertation (Holtved, 1944), and was employed at the University of Copenhagen in 1945 (Lidegaard, 1980:550). Holtved conducted a number of archaeological surveys and ethnographic fieldworks as a university professor. His archaeological surveys in Bristol Bay, Alaska, in 1948 (Figure 10.5) together with Helge Larsen and in Sermermiut, West Greenland, in 1955 with Therkel Mathiassen were of particular importance (Kleivan, 1995:3–4), but his most famous contributions were on the Thule (Polar) Eskimo (Holtved, 1944, 1951, 1954, 1967; see Birket-Smith, 1969–1970).6

Figure 10.4 Erik Holtved in Thule, 1936. © The National Museum of Denmark, Ethnographic Collections.

Figure 10.5 Erik Holtved during an archaeological excavation at Platinum, Alaska, 1948. Photo courtesy Department of Eskimology and Arctic Studies, University of Copenhagen.

In personality, academic style, and interests, Holtved and Thalbitzer showed remarkable differences. Holtved was a quiet figure, less outgoing, and much less controversial than Thalbitzer. Whereas Thalbitzer could be described as a polymath type of academic and at times quite speculative and experimental, Holtved seemed more specialized, sober minded, reserved, and meticulous. In contrast to Thalbitzer, he did archaeological fieldwork—in Thule, other parts of Greenland, and Alaska. He brought a new combination of ethnography and archaeology to Thalbitzer’s vision of the discipline of Eskimology, although he added reminiscences from the philology of Thalbitzer in some of his works. Holtved was concerned with language studies, but compared with Thalbitzer, he took a more practical approach, as evidenced by his long-term engagement in language research and documentation. This approach led to the adoption of a new Greenlandic orthography in 1973 (Petersen, 1979:187–188, 2009) and his collection of comparative Eskimo word stems, later used as an important basic material for the Comparative Eskimo Dictionary published by Fortescue et al. (1994; Fortescue, 1995:32).

The formal end to Greenland’s status as a Danish colony in 1953 was followed by the introduction of the large-scale centralized modernization and industrialization program for Greenland run by the Danish state. Soon it produced a growing interest in Greenland in many Danish university disciplines, among them the social sciences, law, and sociology (Dybbroe et al., 2005:282–285). In 1955, the Committee for Social Scientific Research in Greenland was founded, initially to follow the new criminal legislation for Greenland and “to provide the legislative authority and the administration with a solid foundation for the future work of furthering a calm and harmonious cultural development from old to new” (Dybbroe et al., 2005:285; my translation from Danish). The committee was tasked to organize and implement research requested by the state institutions, including the Danish parliament, the Ministry of Greenland, and the Greenland legislative committee. Committee members were researchers from ethnography, psychology, sociology, economics, history, and Eskimology (Erik Holtved), as well as civil servants from the Greenlandic administration.

It has been argued that although the colonial period formally ended in 1953, the new modernization policy in reality represented a new style of intensified Danish colonialism and that, accordingly, the colonial period did not cease before the passing of the Greenland Home Rule Act in 1979 (see Dahl, 1986:9). The committee was indeed a state-initiated body tied to a large-scale colonial program. However, the committee’s work was gradually influenced by a general contemporary move among university students and young researchers who were engaged in its activities. There was a growing movement that demanded that university research be of practical use to the host society, be it Danish or Greenlandic society or developing countries. The committee’s researchers managed to turn the field of social science studies in Greenland into a stimulating research environment by arranging seminars and courses to discuss social science methodology and fieldwork and via meetings with Greenlandic politicians (Dybbroe et al., 2005:285). The committee’s researchers produced nine impressive reports published in just two years between 1961 and 1963 on various aspects of social impact of the modernization policy: criminal legislation, education, family and marriage, conflicts between Greenlanders and Danes, alcohol abuse, and population and settlement policy (Dybbroe et al., 2005:286).

At the end of the 1960s Danish universities underwent a number of profound reforms. Overall, the traditional university system was confronted by demands of democratic reforms concerning the governance of universities, the relevance of research to society, and access of students from a wider proportion of society to university study programs. Eventually, more teaching staff and young professors were recruited, disciplines were institutionalized, and individual professor chairs became institutes, that is, physical units for administration, research, and education. Representatives of all staff and students were to take part in the councils that ran the institutes’ administration. The reorganization of the university resulted in teams of professors, researchers, lecturers, and students within the same discipline who were physically present in the same rooms. Although some courses or lectures at the University of Copenhagen used to take place in larger lecture halls, for instance, at the National Museum, the idea of a single independent professor teaching his students in his private home was now abandoned.

The new institutes were often placed in large apartments in the inner city of Copenhagen close to the old university buildings. The new structure created a new dynamic, often with the students and young staff members pressuring for new directions and methods within the disciplines.

As a part of university reforms, the Institute of Eskimology was established in 1967 as a stand-alone department, followed by formal study programs that enabled specialization in either ethnology and anthropology or linguistics. During the 1960s, Holtved experienced an increasing number of Eskimology students, as well as students from other disciplines, attending his lectures. After 1967 his lectures were supplemented by those given by lecturers hired from among young Eskimology candidates, such as Robert Petersen, Bent Jensen, and Inge Kleivan. Among the courses in the late 1960s were Greenlandic Literature from Recent Years (Robert Petersen), West Greenlandic Language for Beginners (Bent Jensen), and Greenlandic Traditions and Reality (Inge Kleivan).7 Later, historian Finn Gad taught classes on the history of Greenland and historical methodology. He worked as a research fellow compiling his now well-known work Grønlands historie (1967–1976), later published in English (Gad, 1970–1982; Petersen, 1979:188).

Holtved retired in 1968, and during the following years, the young candidates and lecturers were very influential in creating new directions for the discipline. The reorientation of the Eskimology discipline after the era of Thalbitzer and Holtved can be viewed as resulting from various internal and external influences. Internal organizational changes at the Danish universities, signified by the shift from single-professor research to the new type of research teams made of groups of professors (departments), opened new orientations and agendas for the discipline. Furthermore, the new organization and subsequent expansion of the discipline of Eskimology was a result of the university reform as well as external political movements of the time. Eskimology partly changed from its previous focus on traditional Eskimo culture to contemporary political processes in Greenland and the Arctic (Petersen, 1979:189–190). Robert Petersen described the development of the discipline in an interview in 1975:

It [Eskimology] was originally mainly a philological study, but has since developed with emphasis on other branches of the cultural sciences. Thus, the discipline got a delimitation that covers a certain geographical area, but on the other hand spreads over various disciplines. I do not consider the fact that the discipline today deals a lot with the contemporary situation in the Arctic area as a breakaway from the discipline’s previous orientation, but rather as an update made possible by having more people employed within the discipline than before. (Hansen, 1975:153; my translation from Danish)

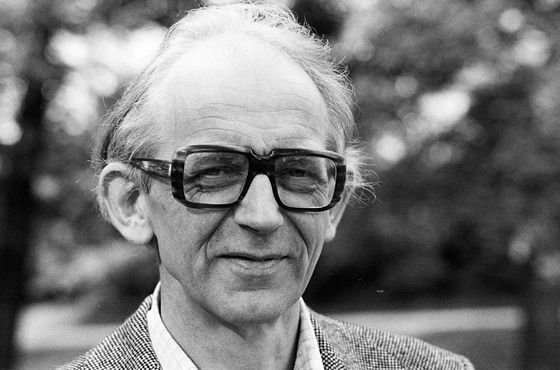

The appointment of a group of new professors at the new Institute of Eskimology occurred in just four years between 1972 and 1976 (Thuesen, 2005a:260–261). After Holtved retired in 1968, it took seven years before his successor, Robert Petersen (Figure 10.6), was appointed as professor in 1975. The further appointment of a group of young associate professors had a major impact on the discipline. The first to get appointed in 1972 were Inge Kleivan and anthropologist Hans Berg, who soon left and established himself as a painter.8 His successor in the position was anthropologist Jens Dahl (b. 1946), who was first appointed as assistant professor and serves today as an adjunct professor at the University of Copenhagen. Jens Dahl made a huge contribution to the field of Eskimology, and he is still an important contributor to research on the issues concerning indigenous peoples’ rights and self-governance in the Arctic and elsewhere.

Figure 10.6 Robert Petersen, 1961. Photo by Jette Bang. © Jette Bang Photos/Danish Arctic Institute, Copenhagen.

Inge Kleivan (b. 1931) was a student of Erik Holtved. She published her first scholarly articles while still a student, and she did fieldwork in South Greenland. Her list of publications is very extensive and includes more than 130 works on a wide range of topics related to Greenland: mythology and religion, sociolinguistics, education, politics, ethnic identity, gender, culture, history, literature, photography, and films (Thuesen, 2001). From the 1970s to 1990, she served on the editorial board of the new Greenlandic-Danish Ordbogi (Dictionary; Berthelsen et al., 1977) and the enlarged version Oqaatsit (Words; Berthelsen et al., 1990) that was produced jointly with other members of the Eskimology staff members. Inge Kleivan retired in 1993 (Thuesen, 2005a:261).

The next associate professor at the Institute of Eskimology was the Norwegian anthropologist Helge Kleivan (1924–1983; Figure 10.7). As a student, he conducted fieldwork in Labrador and published articles about the Labrador Inuit in the Danish journal Grønland, and later his thesis was published in English (H. Kleivan, 1966).9 Helge Kleivan graduated in 1959. He was married to Inge Kleivan. He came from a position at the Department of Anthropology at the University of Copenhagen to an Eskimology position in 1973. The following quotation from Helge Kleivan in 1969 could serve as an illustration of his contribution to the discipline of Eskimology, namely, that researchers (Eskimologists or social scientists) have to be aware of the political character of their research and accept their responsibility toward their violated or exploited fellow human beings:

Figure 10.7 Helge Kleivan, 1924–1983. IWGIA, Copenhagen.

One often comes across the idea that social scientists must refrain from expressing opinions that can be characterized as political. It is high time and we all recognize this dilemma as a part of an old doctrine of academic conduct inherent in contemporary social science. Any concern with politically sensitive issues can be branded as “political,” due among other reasons, to the fact that our research draws its data from human reality, which is at the same time the very object of activities and decisions of politicians.

Confronted by a world where genocide, exploitation and deprivation of control over one’s own life are constant facts of life for fellow human beings, social science must become the indefatigable eye watching over human inviolability. Only then will the social scientist become anything more than a predator consuming data. And only then will the concept of responsibility mean more that a button-hole flower worn at academic ceremonies. (Quoted in Brøsted et al., 1985:11)

The new generation of Eskimologists had already made a stand in 1969 in a publication called Greenland in Focus (Grønland i fokus; Hjarnø, 1969), to which the new cohort of Greenlandic politicians also contributed with their message that Greenlanders ought to have more influence on their affairs. The questions of self-determination and cultural identity were addressed through Helge Kleivan’s introduction of Norwegian anthropologist Fredrik Barth’s concept of ethnicity in a Greenlandic context. A high degree of participation in public debate and contact with Greenlandic politicians concerning issues of collective land rights, traditional law, exploitation of mineral resources, and cultural identity was typical for the Danish Eskimologists of the 1970s. Furthermore, Helge Kleivan had been one of the founders of the International Work Group of Indigenous Affairs in 1968 and, together with Robert Petersen and the Eskimology department, assisted in organizing the historic Arctic Peoples’ Conference in Copenhagen in 1973. It eventually led to the formation of the Inuit Circumpolar Conference in 1977 (Kleivan, 1987:367, 369).

Aqqaluk Lynge, Greenlandic politician, author, and, later, president of the Inuit Circumpolar Council, who was then a member of the Council for Young Greenlanders, described this period and the alliance between Eskimologists and young Greenlandic politicians in the following way:

We demonstrated against the Vietnam war.… There were contacts with American Indians and we had just discovered our [Inuit] tribesmen, and professor Kleivan introduced us to something called the “Fourth World” … and “indigenous peoples” … Everything around us moved. There were a number of university people, who had great influence on us. Robert Petersen’s articles on Greenlandic land rights were dissected to the Councils’ members, and numerous meetings and weekend “teach-ins” were arranged. But it was professor Helge Kleivan, who untiringly taught us not to isolate ourselves as Greenlanders, [and] gave us the argument for the formation of the Inuit movement. (Lynge, 2007:20; my translation from Danish)

Robert Petersen (b. 1928) was appointed professor at the University of Copenhagen in 1975 (Lodberg, 1993b). Petersen was educated as a teacher at Ilinniarfissuaq, the teachers’ training college in Nuuk, Greenland, from which he graduated in 1948. He received a second Danish teacher’s license in 1953 after studying in Denmark. He worked as a teacher at Ilinniarfissuaq from 1954 to 1956. During this time, Petersen took an interest in the Arctic people outside of Greenland. In 1956, he participated in the first organized exchange between Greenlandic and Canadian Inuit, the so-called H. J. Rink Expedition to Baffin Island. In 1951, the Greenland Provincial Council discussed contacting Inuit in Canada, eventually deciding to send a delegation of Greenlanders to visit Inuit communities on Baffin Island, among them Pangnirtung and Iqaluit, in summer 1956. The governor’s travel boat H. J. Rink was used for this purpose, hence the expedition’s name. The delegation included a small group of Greenlanders: Robert Petersen; Peter Nielsen, a member of the Provincial Council; Frederik Nielsen, an author and, later, the head of the Greenland Radio; journalist UvdloriánguaK’ Kristiansen; and Knud Hertling, a lawyer and, later, minister for Greenland (Nielsen, 1956:441). This visit to Canada to experience local culture and the Inuktitut language soon found its way into Petersen’s writings in several articles written in Greenlandic between 1956 and 1958 (see Hansen, 1996:280–281).

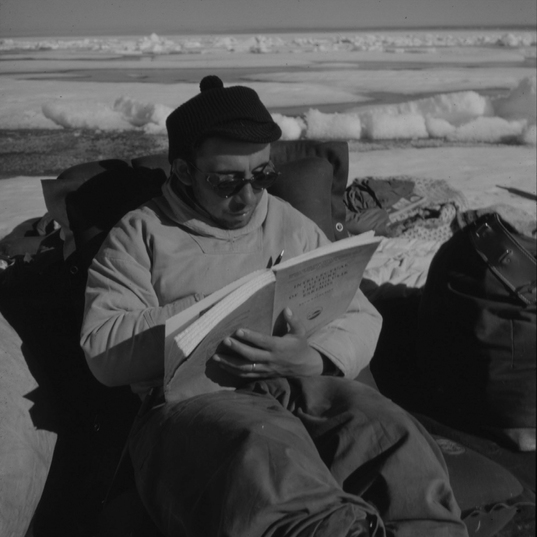

Petersen returned to Arctic Canada the next year (Figure 10.8). This time he participated in an archeological survey in Igloolik with the Danish archaeologist Jørgen Meldgaard.

Figure 10.8 Robert Petersen reading Knud Rasmussen’s The Intellectual Culture of the Iglulik Eskimos while on a boat in the Fury and Hecla Strait, Canada, July 1957. Photo by Jørgen Meldgaard. © The National Museum of Denmark, Ethnographic Collections.

As a teacher in Greenland, Robert Petersen had been concerned with the spelling problems that Greenlanders had in relation to the so-called (Samuel) Kleinschmidt orthography then in use. To solve these problems, he decided to continue his studies at the University of Copenhagen as a student of Holtved (Dorais, 2005:1626). In 1967 he received his degree (artium magister) in what was then termed Greenlandic philology (Skyum-Nielsen, 1968:167). He began teaching in 1967 and became a lecturer at the Institute of Eskimology in 1969, shortly after Erik Holtved’s retirement. Petersen clearly followed in the footsteps of his predecessors, Thalbitzer and Holtved, concerning linguistics and Greenland language issues. Petersen succeeded Holtved as a member of the Greenland Provincial Council’s committee for orthographic reform for the Greenlandic language from 1969 until 1973, when the committee’s proposal for reform was passed (Dorais, 2005:1626). He continued similar work as a consultant for the Canadian Inuit Language Commission from 1973 to 1976.

Robert Petersen’s research resembled that of his predecessors within the discipline in its almost polyhistoric range of topics on Greenland and the Inuit. His research covered everything from literature to religion and culture in both precontact and historic times to history, ethnography and contemporary society, politics, and much more. He published more than 400 books, articles, and reports between 1944 and 1995 (Hansen, 1996). A primary example of his seminal research on social organization is his comparative study of settlement, kinship, and the use of hunting grounds in Upernavik and Ammassalik (Petersen, 2003).

During the 1970s and early 1980s several Greenlandic teaching assistants and external lecturers became part of the Institute of Eskimology’s staff. Christian Berthelsen (1916–2015), who was formerly director of the Greenland School Board, taught both Greenlandic language and literature as an external lecturer in 1977–1986. He published important teaching materials and was the chief editor of the abovementioned Greenlandic-Danish dictionary Ordbogi (1977) and Oqaatsit (1990; Lodberg, 1993a:9–10).

In 1984, teaching and research was further strengthened by the appointment of linguist Michael Fortescue (b. 1946), who had already been associated with the department as a research fellow. Fortescue left Eskimology in 1999 to become a professor in the linguistics department at the University of Copenhagen. His major contribution was the abovementioned Comparative Eskimo Dictionary (1994) published in collaboration with Lawrence Kaplan and Stephen Jakobson from the Alaska Native Language Center at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Robert Petersen left the Institute of Eskimology in 1983, having been given the task of establishing a hub for research and higher education in Nuuk by the new Greenland Home Rule government. Called the Inuit Institute, this new center became a university in 1987 under the name Ilisimatusarfik (Figure 10.9), the University of Greenland, with Robert Petersen serving as its first rector. Petersen’s success in establishing a thriving university in Greenland is one of his greatest life achievements.

The history of Danish Eskimology, from the time of William Thalbitzer to Robert Petersen and the new generation of Eskimologists of the 1970s, is not only a story of how the discipline has changed from a single professor’s project to a team organization of research. It is also a good illustration of how the formation of a university discipline, like Eskimology, can be influenced and shaped by political circumstances, such as changes in colonial relations (in this case, between Denmark and Greenland) or changes in the organization and finance of the discipline within the university structure. In order to assess the influence and outreach of Danish Eskimology, the ideas, methods, and results of the researchers involved must be acknowledged.

Figure 10.9 Robert Petersen being awarded an honorary doctorate at the University of Greenland in 2010. Photo courtesy Ilisimatusarfik (Institute of Culture, Language and History, University of Greenland).

William Thalbitzer’s somewhat vague ideas about creating a discipline he called Eskimology from a combination of perspectives or multidisciplinary components such as Greenlandic (Eskimo) philology, ethnology, and sociology were supported by his own example and by the way in which he conducted his own research. His international publications and outreach influenced generations of Arctic scholars. Erik Holtved followed Thalbitzer, but with his preferred term “Eskimo science” he emphasized even further the pan-Eskimo or pan-Inuit perspective in the discipline. The terms Eskimology and Eskimologist came into use in the late 1960s as a result of the discipline’s institutionalization and the formal creation of the Institute of Eskimology at the University of Copenhagen, a purely Danish matter. The new generation of Danish Eskimologists reoriented the research interests and methods of the discipline, dealt with contemporary issues of decolonization, and worked with the new generation of Greenlandic politicians as well as with indigenous peoples across the Arctic. This approach altered Danish Eskimology profoundly. Furthermore, when a Greenlandic academic, Robert Petersen, was chosen to head the discipline of Eskimology in Denmark, the decision had tremendous impact on the status and development of the discipline, be it internally, internationally, or in relation to Greenland.

After 1979, when Greenland received the home-rule government, new trends within Eskimology emerged, but with ties back to the legacy of Thalbitzer and Holtved. These new developments introduced comparative studies of self-determination processes in the Arctic, including questions of ethnic and national identity, nation building, the history of colonialism and decolonization, globalization, language change, climate change, urbanization, and industrialization. Studies of language, culture, and society from a historical and comparative perspective, most often based on fieldwork, are still part of the Danish Eskimology tradition. Cross-disciplinary and comparative studies of the entire Inuit region continue to be important. The University of Copenhagen is still the only university in the world where one can study Kalaallisut/Greenlandic as a foreign language as part of a full university program. Thalbitzer’s vision of Greenlandic students coming to the University of Copenhagen has come to pass, with a number of young Greenlanders choosing to study Eskimology and Arctic studies at the University of Copenhagen every year.

I give credit to a special issue of the journal Tusaut (nos. 2–3, 1995) on the contributions of Thalbitzer and Holtved produced by a range of my Danish colleagues. This publication has helped me greatly in my research and writing on the history of Danish Eskimology. Furthermore, I express my gratitude to professor emerita Inge Kleivan for her valuable advice and comments on the earlier draft of this paper.

1. For a bibliography of Thalbitzer’s works 1900–1953, see Thalbitzer (1954).

2. It should be mentioned that Danish ethnographer Kaj Birket-Smith used the term “Eskimology” in his book The Eskimos published in Danish in 1927 and in English in 1936, in which Hinrich J. Rink was presented as “the founder of modern Eskimology” (Birket-Smith, 1927:33).

3. In Danish, åndelig kultur.

4. On Svend Frederiksen’s life and research in Greenland, see Avijaja Albrechtsen (2012).

5. After Hammerich’s death in 1975, his journals from fieldwork in Alaska in 1950 and 1953 were published together with a selected bibliography (Hammerich, 1982).

6. For a selected bibliography of Erik Holtved’s publications, see Holtved (1969–1970: 11–12).

7. Bent Jensen’s anthropological research dealt with modernization and urbanization issues (see Jensen, 1965).

8. Before Hans Berg left the Institute of Eskimology, he produced a few articles concerning contemporary Greenlandic sheep farming, which was then a new topic of research.

9. For a selected bibliography of Helge Kleivan, see I. Kleivan (1985).

Albrechtsen, Avijaja. 2012. Svend Frederiksen, 1906–67: Eskimolog, antropolog og projektmager. Nuuk, Greenland: Ilisimatusarfik.

Berthelsen, Christian, Birgitte Jacobsen, Robert Petersen, Inge Kleivan, and Jørgen Rischel. 1990. Oqaatsit. Kalaallisuumiit Qallunaatuumut. Grønlandsk Dansk Ordbog. Nuuk, Greenland: Atuakkiorfik, Ilinniussiorfik.

Berthelsen, Christian, Frederik Nielsen, Inge Kleivan, Robert Petersen, and Jørgen Rischel. 1977. Ordbogi. Kalaallisuumiit Qallunaatuumut. Grønlandsk Dansk. Copenhagen: Ministeriet for Grønland.

Birket-Smith, Kaj. 1927. Eskimoerne. Copenhagen: Gyldendal.

———. 1969–1970. Erik Holtved, the Eskimologist. Folk, 11–12:7–10.

Boas, Franz. 1888. The Central Eskimo. In Sixth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1884–’85, pp. 399–669. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

Brøsted, Jens, Jens Dahl, Andrew Gray, Hans Christian Gulløv, Georg Henriksen, Jørgen Brøchner Jørgensen, and Inge Kleivan, eds. 1985. Native Power: The Quest for Autonomy and Nationhood of Indigenous Peoples. Bergen, Norway: Universitetsforlaget AS.

Dahl, Jens. 1986. Arktisk Selvstyre. Copenhagen: Akademisk Forlag.

Dorais, Louis-Jacques. 2005. “Robert Petersen.” In Encyclopedia of the Arctic, ed. M. Nuttall, pp. 1626–1627. New York: Routledge.

Dybbroe, Susanne, Frank Sejersen, Hanne Petersen, Jens Dahl, and Gorm Winther. 2005. “Hundrede års dansk samfundsforskning.” In Grønlandsforskning: Historie og perspektiver, ed. K. Thisted, pp. 280–307. Det Grønlandske Selskabs Skrifter 38. Copenhagen: Det Grønlandske Selskab.

Fortescue, Michael. 1995. Thalbitzers og Holtveds betydning for eskimoisk lingvistik. Tusaut. Forskning i Grønland, 2–3:29–32.

Fortescue, Michael, Lawrence Kaplan, and Stephen Jakobson. 1994. Comparative Eskimo Dictionary: With Aleut Cognates. Alaska Native Language Center Research Paper 9. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Gad, Finn. 1970–1982. The History of Greenland. Volumes 1–3. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press. [Danish edition, Copenhagen: Nyt Fordisk Forlag.]

Gulløv, Hans Christian. 1995. Lyde og billeder fra fortiden: Thalbitzers og Holtveds arbejde med et arkæologisk materiale. Tusaut. Forskning i Grønland, 2–3:16–19.

Hammerich, Louis L. 1959. William Thalbitzer. 5. februar 1873—18. september 1958. Tale i Videnskabernes Selskabs møde den 20. februar 1959. Særtryk af Oversigt over Det Kgl. Danske Videnskabernes Selskabs Virksomhed 1958–1959. Copenhagen: Det kgl. Danske Videnskabernes Selskab.

———. 1982. Vesteskimoernes land. Copenhagen: Geislers Forlag.

Hansen, Keld. 1975. Robert Petersen. Interview ved Keld Hansen. Tidsskriftet Grønland, 6:153–158.

Hansen, Klaus Georg. 1996. “Robert Petersen: Bibliography 1944–1995.” In Cultural and Social Research in Greenland 1995/96. Grønlandsk kultur- og samfundsforskning 1995/96, ed. B. Jakobsen, C. Andreasen, J. Rygaard, pp. 279–309. Nuuk, Greenland: Ilisimatusarfik/Atuakkiorfik.

Hjarnø, Jan, ed. 1969. Grønland i fokus. Copenhagen: Nationalmuseet.

Holm, Gustav F. 1888. Ethnologisk skizze af Angmagsalikerne. Meddelelser om Grønland, 10(2):43–182.

Holtved, Erik. 1944. Archaeological Investigations in the Thule District. Volume I: Descriptive Part. Volume II: Analytical Part. Meddelelser om Grønland, 141(1–2).

———. 1951. The Polar Eskimos: Language and Folklore. Part I: Texts, Part II: Myths and Tales. Meddelelser om Grønland, 152(1–2).

———. 1954. Archaeological Investigations in the Thule District. Volume III: Nûgdlît and Comer’s Midden. Meddelelser om Grønland, 146(3).

———. 1967. Contributions to Polar Eskimo Ethnography. Meddelelser om Grønland, 182(2).

———. 1969–1970. Selected Biography. Folk, 11–12:11–12.

Høiris, Ole. 1986. Antropologien i Danmark: Museal etnografi og etnologi 1860–1960. Copenhagen: Nationalmuseets Forlag.

———. 2009. “William Thalbitzer.” In Grønland—en refleksiv udfordring: Mission, kolonisation og udforskning, ed. O. Høiris, pp. 211–237. Århus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag.

Jensen, Bent. 1965. Eskimoisk festlighed, et essay om menneskelig overlevelsesteknik [Eskimo festivity, an essay on human survival technique]. Copenhagen: Gad.

Kleivan, Helge. 1966. The Eskimos of Northeast Labrador: A History of Eskimo-White Relations, 1771–1955. Oslo: Norsk polarinstitutt.

Kleivan, Inge. 1985. “Helge Kleivan Selected Bibliography.” In Native Power: The Quest for Autonomy and Nationhood of Indigenous Peoples, ed. J. Brøsted, J. Dahl, A. Gray, H. C. Gulløv, G. Henriksen, J. B. Jørgensen, and I. Kleivan, pp. 342–348. Bergen, Norway: Universitetsforlaget AS.

———. 1987. Institute of Eskimology, University of Copenhagen, Danmark. Inter-Nord, 18:367–371.

———. 1995. William Thalbitzer og Erik Holtved. Tusaut. Forskning i Grønland, 2–3:3–6.

Lidegaard, Mads. 1980. “Erik Holtved.” In Dansk biografisk leksikon, p. 55. Copenhagen: Gyldendal.

Lodberg, Torben, ed. 1993a. “Christian Berthelsen.” In Grønlands grønne bog, p. 9. Copenhagen: Grønlands hjemmestyres Danmarkskontor.

———, ed. 1993b. “Robert Karl Frederik Petersen.” In Grønlands grønne bog, pp. 85–86. Copenhagen: Grønlands hjemmestyres Danmarkskontor.

Lynge, Aqqaluk. 2007. “Da Grønland blev en del af verdenssamfundet: De unge grønlænderes politiske engagement fra 1971–76.” In København som Vestnordens hovedstad, ed. A. Mortensen, J. Th. Thór, and D. Thorleifsen, pp. 16–21. Nuuk, Greenland: Atuagkat.

Mauss, Marcel. [1904–1905] 1979. Seasonal Variations of the Eskimo: A Study in Social Morphology. In collaboration with Henri Beuchat. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. [Originally published as Essai sur les variations saisonnières des sociétés Eskimo: Essai de morphologie sociale. L’Année Sociologique, 9 (1904–1905):39–132.]

Nellemann, Georg. 1995. Erik Holtveds vej til eskimologien. Tusaut. Forskning i Grønland, 2–3: 12–13.

Nielsen, Frederik. 1956. Besøg hos eskimoiske stammefrænder på Baffinland. Tidsskriftet Grønland, 12:441–450.

Petersen, Robert. 1979. “Eskimologi.” In Københavns Universitet 1479–1979. Bind 9: Det filosofiske Fakultet, 2. del., ed. Svend Ellehøj, pp. 177–194. Copenhagen: Gad.

———. 1995. Thalbitzers og Holtveds undervisning på Københavns Universitet. Tusaut. Forskning i Grønland, 2–3:60–61.

———. 2003. Settlements, Kinship and Hunting Grounds in Traditional Greenland: A Comparative Study of Local Experiences from Upernavik and Ammassalik. Meddelelser om Grønland 327, Man and Society 27. Copenhagen: Danish Polar Center.

Skyum-Nielsen, Ingrid. 1952. Årbog for Københavns Universitet 1948–53. Copenhagen: Bianco Luno.

———. 1968. Årbog for Københavns Universitet 1966–67. Copenhagen: Bianco Luno.

Thalbitzer, William. 1904. A Phonetical Study of the Eskimo Language Based on Observations Made on a Journey in North Greenland, 1900–1901. Meddelelser om Grønland, 31.

———. 1911. “Eskimo.” In Handbook of American Indian Languages, ed. F. Boas. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 40(1), pp. 967–1096. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

———. 1914–1941. The Ammassalik Eskimo: Contributions to the Ethnology of the East Greenland Natives. Meddelelser om Grønland, 39–40, 53.

———. 1917. The Ammassalik Eskimo: A Rejoinder. Meddelelser om Grønland, 53(5):435–481.

———. 1937–38. “Forelæsninger ved Københavns Universitet, Vinteren 1937/38.” Unpublished manuscript, Archive of the Eskimology and Arctic Studies Section, University of Copenhagen.

———. 1940. Gustav Holm. Det grønlandske Selskabs Aarsskrift, 1940, 5–23.

———. 1943. Universitet-imit: Fra Universitetet. Kalâtdlit, 6:3–5.

———. 1954. Bibliografi 1900–1953. Meddelelser om Grønland, 149(1).

Thisted, Kirsten, ed. 2005. Grønlandsforskning: Historie og perspektiver. Det Grønlandske Selskabs Skrifter 38. Copenhagen: Det Grønlandske Selskab.

Thuesen, Søren. 2001. Inge Kleivan, født Parbøl: Bibliografi for årene 1954–2000. Tidsskriftet Grønland, 4–5:206–211.

———. 2005a. “Eskimologi—en dansk universitetsdisciplin.” In Grønlandsforskning: Historie og perspektiver, ed. K. Thisted, pp. 253–264. Det Grønlandske Selskabs Skrifter 38. Copenhagen: Det Grønlandske Selskab.

———. 2005b. “Eskimology.” In Encyclopedia of the Arctic, ed. M. Nuttall, pp. 585–586. New York: Routledge.