“You must be shapeless, formless, like water. When you pour water in a cup, it becomes the cup. When you pour water in a bottle, it becomes the bottle. When you pour water in a teapot, it becomes the teapot. Water can drip and it can crash. Become like water my friend.”

—Bruce Lee

“It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent; it is the one most adaptable to change.”

–Charles Darwin

When I first started in brand management there was an ongoing debate about whether or not Western brands could succeed by focusing on exporting their standard products into developing markets with little to no adaptation. In the early 2000s, there wasn't a strong need to adapt because when most Western brands expanded into developing markets, they didn't face serious competition in terms of quality. The situation has changed. Local brands continue to improve and develop new products specifically tailored to meet the needs of emerging consumers. Today, aspiring global brands must accept what they had long tried to ignore: global brands do need to adapt to win in local markets.

As a child, I remember when Japan had a reputation for making inexpensive toys, knockoffs, and trinkets that many Americans classified as “cheap” in both price and quality. With Japan's embrace of Dr. Deming's statistical quality control and the rise of titans like Sony, Nissan, Honda, and Toyota, those perceptions faded. It wasn't long after that when Japanese brands became synonymous with high quality.

As a teenager, I remember having a similar attitude toward products made in Korea. A high school friend of mine owned an early model Kia that was inexpensive, noisy, and didn't brake well. I can recall buying a Goldstar VHS player from Costco because I couldn't afford a higher quality, more expensive Sony model. As an adult, I find the quality of Korean products is revered around the world: LG (Lucky-Goldstar) became famous for its paper-thin television screens; Kia and Hyundai make some of the safest and bestselling cars in the world, and Samsung is now the world's second largest phone manufacturer after Apple.

No longer can developed market brands simply assume they will have an advantage when it comes to quality. Even if a developed market brand manages to create a quality advantage, it will only be a matter of time until a developing market brand catches up, proving that the necessity for building strong brands has never been more important. Brands are what separate commodities from higher margin premium-priced products. A global survey conducted by Nielsen found that 38 percent of all respondents believe a product produced by a well-known or trusted brand makes the product more “premium.”1

With more global marketers in agreement that one size does not fit all, the term “GLOCAL” (Think Global, Act Local) has been getting a lot more use in marketing circles. According to the American Marketing Association, “The term GLOCAL has been coined to describe an organizational approach that provides clear global strategic direction along with the flexibility to adapt to local opportunities and requirements.”2

Nike CEO Mike Parker recently announced that the company would begin to develop what he called a “local business, on a global scale” and “deeply” serve customers in a dozen key cities, including New York, Paris, Beijing, and Milan. These twelve mega-cities are expected to deliver 80 percent of Nike's growth during the next two and a half years.3

A global survey conducted by Millward Brown across eight countries revealed that although global brands tend to be stronger than local brands overall, local brands generally score higher on being part of a national culture, which research shows is a major driver of purchase intent.4

Experience has taught me that when a global brand is planning to enter an international market, the million-dollar question is: What parts of the existing value proposition need to be adapted and which parts should remain consistent with the global strategy?

When trying to decide what to adapt, it's helpful to drill down to the attributes that will most likely influence consumers as they make their purchasing decision. That's why I developed the following framework for helping my teams zoom in on categories of brand associations that most influence the purchase of a foreign brand (see Figure 6.1).

Figure 6.1. Categories of brand associations that influence the purchase intent for foreign brands.

In reality, all of these factors are highly correlated, so it's the thought process that is important to master. Feel free to add or subtract associations that you believe are more relevant to the product category you are entering. Remember: The weighting of associations is highly dependent on the product category, target market, and competitive environment.

To gain clarity on which parts of the value proposition need to be adapted, evaluate your brand on each of the six categories of associations that tend to influence the purchase intent for foreign brands. Do this to determine whether or not a category represents an area of strength or weakness for your brand versus competitors. If the category is a strength, ask what adaptations can be made to make the associations stronger. If the category is a weakness, ask what adaptations can be made to make the associations become more advantageous for your brand.

Figure 6.2. Global brand adaptation framework.

Then, evaluate your key competitor on each of the same six categories versus your brand. Just as you did with your brand, assess if a category represents an area of strength or weakness, but this time judge from the perspective of the competitor. If the category is perceived to be a strength for your competitor, look for associations that you can add to your brand that would make consumers perceive that area to be less strong for your competitor. Similarly, if the category is perceived to be a weakness for the competitor, try to identify associations that can be added to your brand to take advantage of the perceived weakness (see Figure 6.2 on page 111).

The following section discusses each category of associations in more detail using select case studies to bring the evaluation process to life.

Many marketers believe that a product's “actual” performance is where the “rubber meets the road,” but Al Ries believes “perceived” performance is actually more important. In his AdAge article, “Having a Better Brand Is Better Than Having a Better Product,” Ries argues that there “. . . are no superior products. There are only superior perceptions in consumers' minds.”5

I admit that's a provocative statement, but one with a lot of truth to it. This is because the technical differences between leading brands are usually very small. Compare the performance reviews for leading mobile phones and you will see just how true this is.

To use an American football analogy, I am a firm believer that product performance needs to get you into the red zone (the area of the field between the 20-yard line and the goal line). After which, it is up to the brand equity you have created to get you over the goal line. Don't get me wrong. If there is a product gap, by all means close it. Your main objective is to always strive to be better than the competition, but don't forget that your competition is doing the same thing. Inevitably, you will have to accept that from time to time your actual product advantage may be negligible.

During my tenure at Nestlé's global policy was not to launch a new product unless it scored at least a 60 percent preference versus the competition in blind taste testing. If you're wondering why the bar was set at only 60 percent, it turns out it is very hard to develop new products that taste better than that of leading competitors. The best brands in the world are all simultaneously investing R&D resources into discovering new ways to exceed consumer expectations through renovation and innovation.

So why do consumers have very specific brand preferences when so many branded products are actually the same from a technical perspective? At the end of the day, it boils down to the power of the brand. Perceived performance is only the “perception” or “estimate” of a brand's actual quality in the minds of consumers.

This means, in order to elevate perceived performance in the minds of consumers you can and should always try to create brand associations that generate positive performance perceptions.

The following examples examine ways in which some brands have strengthened their perceived performance by amplifying and dampening brand associations.

“Birds of a feather flock together” makes sense, right? As you might expect, research supports that people are attracted to others who hold similar views and express similar attitudes, and the attraction increases with the more they have in common.6 A study using behavioral data collected from Facebook “likes” and status updates confirms that “people date and befriend others who are like themselves.”7 This is really good news for brand builders. Since consumers intuitively believe birds of a feather do indeed flock together, you can borrow brand associations from other brands that have stronger perceived performance by simply placing your brand in close proximity.

We all know instinctively that a retailer's store environment and image affect how consumers view the products sold in that store. There is research that takes this further by suggesting that when a low-image brand is placed in a high-image retailer, consumer perceptions regarding the low-image brand significantly increase.8 That is why new fashion designers will do almost anything for the opportunity to get their brands carried by a specialty retailer like Barneys New York.

Barneys is a high-end specialty department store with twenty-four shops located in the United States and twelve licensed shops in Japan. According to Executive Chairman Mark Lee, Barneys tries to offer the most beautiful and best products in the world.9 The CEO of Barneys, Daniella Vitale, says her team “is committed to securing exclusive product and developing emerging brands at every price point.”10

Barneys has received a lot of attention for its exclusive artist and designer collaborations. Jay Z, Russell Westbrook, and Justin Bieber are just some of the celebrities and artists who have created items exclusively for Barneys (see Figures 6.3 and 6.4).

Consumers believe that if a brand is carried by Barneys, it must be prestigious. The brands selected benefit from the consumer perception that the specialty retailer only carries high-quality brands.

Figure 6.3. Justin Bieber's collaboration with Barneys. Photo credit: James Devaney/Getty. Images for Barneys New York

Figure 6.4. Jay Z's “A New York Holiday” gift bags at Barneys. Source: Sagmeister & Walsh

It is not always possible to get listed into a retailer like Barneys to amplify your brand's performance perceptions. However, there are many other things that you can do to augment the way your brand is presented to the consumer.

When entering a new market, the performance perception of your brand may be low because consumers are unfamiliar with the brand. In this case, you can use in-store point-of-sale (POS) materials, product displays, and sampling to amplify perceptions and shape how consumers view your brand.

Innisfree is a very popular Korean cosmetics company with more than four hundred locations in South Korea alone. The brand focuses on skin care and promises consumers healthier looking skin when consumers use its natural products. Innisfree relies on the origin of its ingredients as a primary reason to believe in the brand's promise. The ingredients are sourced from Jeju Island in South Korea, which is known for its “clear fresh air, soft warm sunlight, fertile healthy soil and pure water.”11

While the majority of South Korean's are very familiar with the wonders of Jeju Island, foreign consumers need to be educated about the island and all the benefits that come from these pure ingredients.

Suh Kyung-Bae, the company's chairman and CEO says, “Whenever we go into a new country, we need to first understand what our customers like and how best to communicate the brand story.”12 When Innisfree builds a new store in an international market, the company creates highly visual, interactive displays that bring the Korean brand story to life. Since Innisfree can't assume foreign consumers will know about Jeju Island, it goes to great lengths to describe the origin of ingredients and the various features of the popular Korean island (see Figures 6.5 and 6.6).

Figure 6.5. Innisfree store display in Shanghai highlighting different areas of Jeju Island, Korea. Photo credit: Amy Hsu

Figure 6.6. Innisfree China in-store display educating consumers about Jeju Island, Korea. Photo credit: Amy Hsu

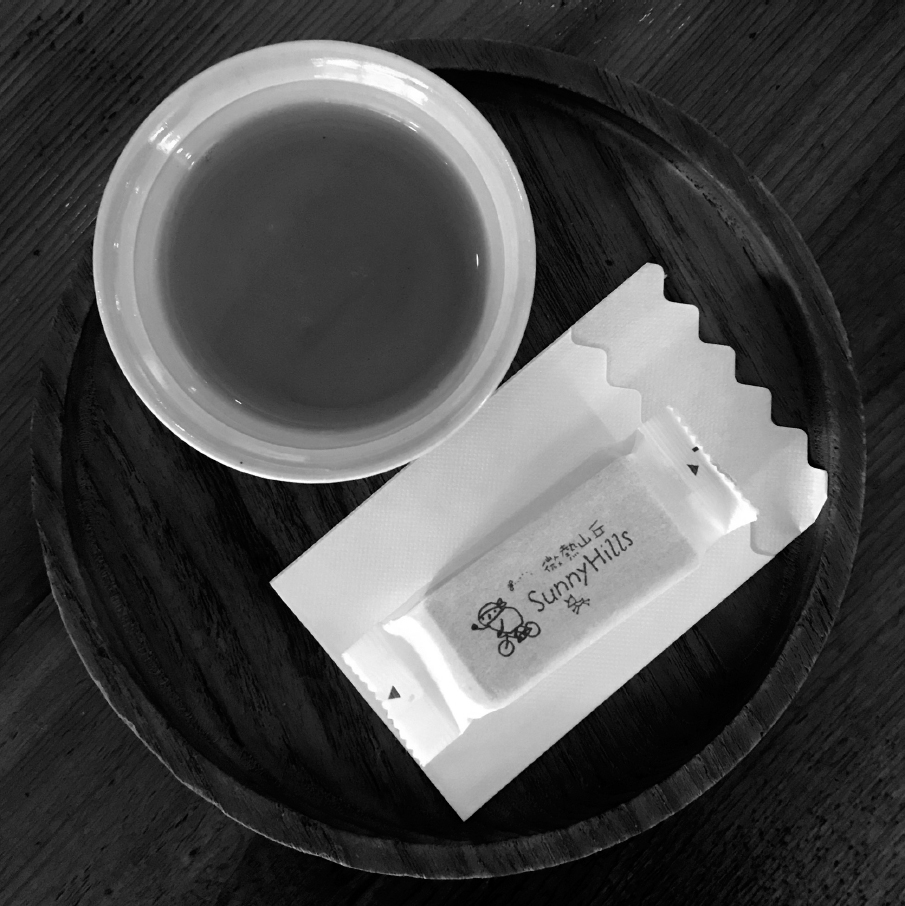

Sunny Hills is a premium positioned bakery concept that uses a romantic ingredient story to support its high-quality offering. Sunny Hills launched in Taiwan and is now expanding throughout Asia with locations in Singapore, Japan, and Mainland China.

If you are not from Taiwan, then you are probably not aware of how Sunny Hills uses delicious pineapples grown in “the sunny and rugged countryside of Bagua Mountain in central Taiwan.”13 Bagua is famous for its tea, pineapples, and a big statue of Buddha.

Sunny Hills uses an engaging sampling ritual to help elevate quality perceptions. Upon entering a store, customers are offered a “complimentary piece of pineapple cake, with a light, flaky crust and a gooey pineapple jam filling, accompanied by a cup of oolong tea.”14 Then, a brand advocate will tell interested customers about how the pineapple cakes taste the way they do because of the delicious pineapples sourced from Bagua Mountain (see Figure 6.7).

Figure 6.7. Sunny Hills in-store ritual sample of pineapple cake and tea. Photo credit: Amy Hsu

I recently received a delicious sample cup of Nespresso coffee made from single origin coffee beans while browsing in a shopping mall in Shanghai. These days, I've been noticing many more Nespresso boutiques, with their modern and sophisticated décor, intentionally located in high-end shopping malls throughout Asia (see Figure 6.8).

Figure 6.8. Nespresso Boutique, Taiwan. Photo credit: Amy Hsu

Nestlé, a company not really known for its cool factor, has positioned the Nespresso brand in China as part of a sophisticated lifestyle.15 Nespresso has become an aspirational brand in China, representing one of the fastest growing markets for the brand globally.

For years, as I traveled throughout the Asia region, I noticed stylish, little Nespresso machines strategically placed in trendy, aspirational locations like five-star hotels, creative agencies, and luxury fashion boutiques (see Figure 6.9).

Figure 6.9. Hotel room Nespresso machine. Photo credit: Amy Hsu

Alfonso Troisi, the country manager of Nespresso China, says Chinese consumers want “a full shopping experience” and most of them spend a minimum of thirty minutes at Nespresso's boutique stores, talking to coffee specialists about their preferences and departing with their own personalized collections.16 Through its boutiques and by partnering with trendy, high-end establishments and brands, Nespresso is building positive perceptions regarding quality and performance, while also linking the brand closely with a modern, sophisticated lifestyle.

Creating brand alliances gives you an opportunity to borrow positive associations from other brands. There is a lot of flexibility when it comes to creating brand alliances because connections can be formed in multiple ways, as illustrated in the following examples.

China's Huawei is the world's largest telecommunications equipment manufacturer and third largest smartphone brand in the world. Richard Yu, the company's CEO, publicly stated that his goal for the brand is to become the second-largest smartphone brand.17

Huawei's technology is very competitive by all accounts. However, research conducted in Western Europe found that Huawei's brand image, when compared to Apple and Samsung, was negatively affected by a country-of-origin bias with regards to product quality.18 In 2017, Huawei's YouGov BrandIndex Impression score, a measurement of how positive consumers are feeling about a brand, scored Huawei around the (+4) mark,19 compared to brands like Apple iPhone and Samsung that scored considerably higher at roughly (+28).20

Huawei has built several brand alliances to help combat this perception and elevate quality perceptions internationally. It recently launched a line of mobile phones that are cobranded with the Leica brand (see Figure 6.10).

Figure 6.10. Huawei coengineered with Leica in-store signage. Photo credit: Amy Hsu

Leica is an internationally operating, premium-segment manufacturer of cameras and sport optics products. The Leica brand has a very high-quality image that traces back to 1925 in Germany, and cobranding provides a strong reason for consumers to believe in Huawei's high performance (see Figure 6.11).21

Huawei also sells a cobranded Porsche design phone and makes use of various sponsorships and celebrity endorsements to help elevate performance perceptions. For example, the brand sponsors several high-performing football teams across Europe including Arsenal, Borussia Dortmund, and Ajax Amsterdam. To launch its new flagship smartphones in the West, Scarlett Johansson and Henry Cavill, who both play superheroes on screen, were hired to boost awareness and performance perceptions (see Figure 6.12).

Figure 6.11. Huawei in-store advertisement featuring Leica brand alliance. Photo credit: Amy Hsu

Figure 6.12. Huawei billboard advertisement featuring Scarlett Johansson and Henry Cavill. Photo credit: istanbulphotos/Shutterstock

If you want to increase the perceived performance of your brand in the minds of consumers, consider fine-tuning your brand's use of semiotics. Marketing semiotics is the study of how consumers interpret design, language, visuals, and even sound to make sense of a brand's positioning and value offering.

According to Laura Oswald, author of Creating Value, the Theory and Practice of Marketing Semiotics Research, each product category has a defined semiotic code.22 These symbolic codes vary by market and are formed in the minds of consumers over time as a result of brands using common symbols in their advertising, packaging, and communication materials. For example, in most markets, a picture of a heart tells consumers that a product is heart-healthy, a cartoon mascot indicates that a product is for kids, and the color black usually indicates a premium positioning. Brand builders can take advantage of how consumers rely on semiotic codes to provide a shortcut for understanding products, and intentionally reinforce a desired brand positioning and value proposition.

In China, there are an estimated 335 million teenagers, and Coca-Cola would like them all to fall in love with the Coke brand. Unfortunately for Coke, there is a lot of competition, with roughly one thousand ready-to-drink beverage options vying for the attention of China's prized younger consumers.

Today, Coke is facing a global problem because it's losing the battle with younger consumers who represent the future of the brand. Younger consumers are increasingly opting for drinks like noncarbonated teas, water, or juice that seem healthier. As a result, Classic Coke's market share is declining globally, and the brand is now under-indexing in the very important eighteen to twenty-four age group.23

Coca-Cola China recently launched thirty-five limited edition Coke labels designed to resonate with Chinese teenagers by speaking to them in their own youth language (see Figure 6.13).

The new labels were co-created with McCann Worldgroup and contain a mixture of emoticons, numbers, characters, and graphics representing authentic “code” that Millennials use to text phrases like “I love you” and “Good luck.”

Shelly Lin, Coke's marketing director for China, explained, “Nowadays in China, teens are using modern communication that is more than language and they have created a lot of new ways to express themselves. We thought that we can build a meaningful conversation with millennials by speaking their language, instead of just borrowing icons that are already there.”24

Coca-Cola China is also using teenage celebrity endorsers, such as pop star sensation Lu Han, to promote its new bottles and engage with his more than forty million Weibo social media followers (see Figure 6.14).25

Figure 6.13. Coca-Cola China's limited-edition “code” packaging targeted at younger consumers. Source: Coca-Cola, used with permission

Figure 6.14. Coca-Cola China promotional materials featuring Lu Han. Photo credit: Amy Hsu

According to a study conducted by McKinsey & Company, word of mouth plays a larger role in the decision-making process of emerging-market consumers than it does in developed markets. This is mainly due to “the higher mix of first-time buyers, a shorter history with the brand, a culture of societal validation, and a fragmented media landscape.”26 First-time buyers in a market where a brand is not well-known need extra assurances that the brand in question will perform as promised.

Therefore, the source of information becomes very important in an emerging market where consumers trust what real people tell them more than advertising slogans from unknown companies.

The cleaning and disinfectant brand Dettol wanted to relaunch into tier-two Chinese cities like Nanjing where less than 10 percent of households were using the brand. The Dettol team conducted a series of ethnographies in Nanjing designed to gain a better understanding of how consumers were using the brand. What it found was that moms in Nanjing were using Dettol only for big tasks like deep cleaning and washing floors even though the product works well for many smaller everyday tasks like sanitizing hands and keeping kitchen surfaces clean.

In order to encourage consumers to use Dettol more often, the brand team hired Advocacy, a word-of-mouth agency, to recruit four thousand high-profile influencers from Nanjing who had the potential to become brand ambassadors. The group consisted of local moms who each had a large network of friends. Influencers were given ten small spray bottles of Dettol to share with their networks. The bottles were an instant hit. In fact, they were so popular that another fifty thousand bottles had to be produced immediately to satisfy demand.

Through this campaign, Dettol was able to reach 46 percent of its target consumers in Nanjing. Top-of-mind awareness for the brand increased 500 percent, and shipments for the brand rose by more than 80 percent versus the precampaign average. Advocacy claims that this campaign was fifteen times more efficient than television.27

When launching a brand into an international market, it's important to be aware of how your brand's country of origin (COO) will be perceived by the local target consumers. When the COO is viewed as a positive, you can then look for ways to amplify the positive associations. When the COO is negative, you need to dampen that perception by augmenting the way the COO is expressed to the consumer.

Nielsen completed a global survey in 61 countries and found that nearly three-quarters of the respondents claim COO is an important factor when making a purchase decision. Furthermore, developing-market respondents were “more likely than their developed-market counterparts to say that local brands are more attuned to their personal needs/tastes,” but that “global brands offer the latest product innovations and are of better quality.” Nielsen found that across markets, there are some general preferences for specific product categories. For example, respondents typically preferred local COO brands when it came to food items.28

Although Japanese consider hamburgers to be an American food, most will tell you that Japan has perfected the classic American fast food. For example, one of my favorite burger shops in the world is located in Tokyo at Omotesando Hills Shopping Center. The little shop is called Golden Brown, and it is known for its gourmet-style burgers made from grass-fed Australian beef and fresh buns baked with wild yeast. The store sells nearly three thousand burgers a week.29 When I observed the guys in the kitchen at Golden Brown making their burgers, I couldn't help but feel as if I were watching artisans at work. With each ingredient prepared and placed on the burgers with careful precision, I wondered if this was the way burgers were made back in the 1950s before they became a mass-produced product (see Figure 6.15).

Figure 6.15. Golden Brown Burger, Japan. Photo credit: metamorworks/Shutterstock

There are an estimated two thousand independent burger shops in Japan, as well as big burger chains like McDonald's, Burger King, and MOS burger (a Japanese chain).30 All of them have menus that have been adapted to cater to the tastes of local Japanese consumers. In fact, McDonald's Japan recently decided to discontinue the classic American Quarter Pounder to make room for more Japan-friendly items like the popular Ebi Filet-O, Teriyaki McBurger, and McPork.

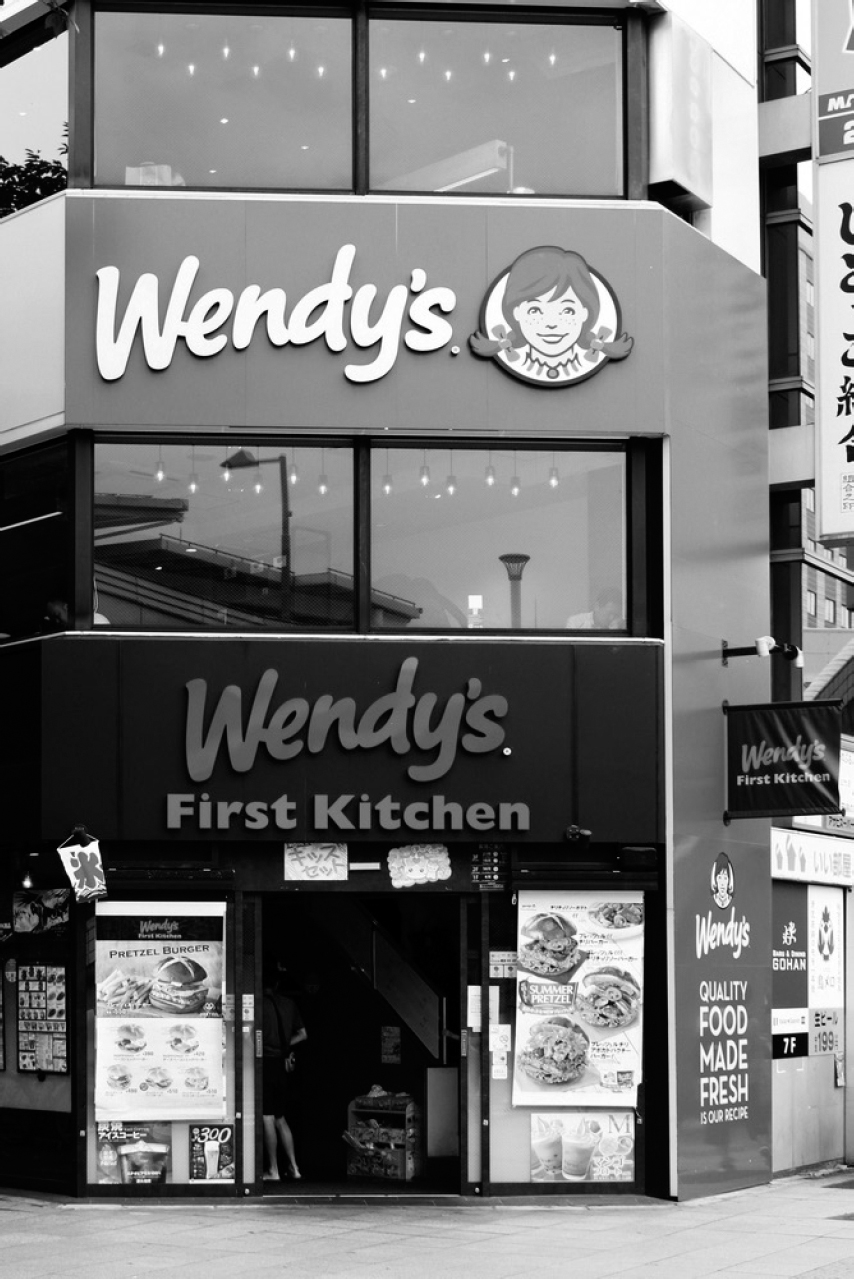

In 2016, Wendy's announced a relaunch of its brand into the Japanese market. As part of its relaunch strategy, Wendy's Japan acquired First Kitchen, a popular Japanese fast-casual chain with more than 130 locations throughout Japan. First Kitchen is well known for its Japanese-friendly menu and for placing a heavy emphasis on pasta and burgers. To support the relaunch, Wendy's rebranded all of the First Kitchen stores to Wendy's First Kitchen (see Figure 6.16). The new concept offers a blended menu from both Wendy's and First Kitchen's existing menus.

By cobranding with First Kitchen, Wendy's was able to dampen the negative associations of being just another American fast-food chain, and lowered the risk of trial for Japanese consumers since First Kitchen is already a trusted brand in Japan.

Figure 6.16. Wendy's First Kitchen, Japan. Photo credit: Ned Snowman/Shutterstock

Beats by Dr. Dre (Beats) is a leading audio brand that was founded by the legendary Dr. Dre and Jimmy Iovine. Beats was acquired by Apple in 2014 and has consistently shown an ability to use its team of international brand ambassadors to generate word of mouth in local markets.

According to Omar Johnson, the company's CMO, the brand ambassadors or “influencers,” as he calls them, play a critical role in Beats campaigns. He refers to them as the “ingredients” that build campaigns. Johnson says that the influencers “live in culture, music, sports, art and fashion, and as much as we're good communicators, our strongest muscle as a brand is our listening muscle. We listen to influencers, we talk to them and build relationships.”31

Figure 6.17. Beats by Dre in-store poster, Shanghai. Photo credit: Amy Hsu

In 2015, Beats partnered with Universal Pictures to promote the movie Straight Outta Compton, which tells the story of how Dr. Dre's hip-hop group NWA rose to fame. To get consumers excited about the movie and promote Beats products, the brand activated its network of international influencers to introduce www.StraightOuttaSomewhere.com to its fans.

The site enabled visitors to create custom memes that highlighted the cities where they came from. For example, in China, Beats partnered with Kris Wu, a famous Chinese rapper and actor, to represent his hometown of Guangzhou. Beats made Kris an official spokesperson for the brand and was able to engage with his 11.7 million Weibo followers (see Figure 6.17 on page 130).32

The campaign was a huge success. Beats became the first brand in history to be the number-one trending topic on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram all at the same time, with 8.7 million memes created and shared via social media.33

Beats continued to build on that momentum by launching the “Straight Outta Asia” campaign that encouraged regional pride by featuring a wide range of Asian influencers that included musicians, actors, artists, and media personalities (see Figures 6.18 and 6.19).34

In most Asian countries, China is currently perceived to have more influence than the United States. In many Asian countries there are also many Chinese consumers who now believe the United States doesn't want China to get any stronger.

A Pew Research Center survey conducted in 2015 found that “More than half (54 percent) of Chinese believed the United States was trying to prevent China from becoming as powerful as the United States. Only 28 percent said the United States accepts that China will become as powerful.”35

Figure 6.18. A Shanghai-based singer on a Beats poster in a Shanghai shopping center. Photo credit: Amy Hsu

Figure 6.19. A Chinese model on a Beats poster in a Chinese mall. Photo credit: Amy Hsu

Figure 6.20. Countries with the strongest influence in Asia.

Helen Wang, an expert on China's middle class, says that Chinese youth are conflicted between their national pride and their love for Western brands. In Forbes, she wrote about how Victoria Secret failed at an attempt to appeal to Chinese Millennials when it used Western models to showcase its dragon-themed lingerie. Many Chinese consumers took to social media and complained how the outfits were distasteful and didn't represent real Chinese culture.36

There is always the risk that if not executed properly, local consumers can experience cognitive dissonance when a global brand enters a local market. By having international influencers “represent” not only Beats but also their hometowns, the Beats brand became more relevant to local consumers, and was able to dampen potential negative associations arising from an American brand promoting itself in a market like China.

Consumers need to be able to accurately gauge a product's usage occasion to evaluate the brand's value proposition. When consumers are unable to categorize the brand offering correctly, it can spell disaster, as illustrated in the following story of the launch of Trix breakfast cereal in China.

To prepare for our launch of Nestlé breakfast cereals into China in 2002, my team conducted extensive focus groups with local Chinese consumers to evaluate the existing offerings from our global portfolio. It caught us totally by surprise that when we showed Chinese consumers cereal packages from developed markets, most of the respondents had no idea what the intended usage occasion was or even how breakfast cereal should be eaten.

Breakfast cereal packaging from developed markets like the United Sates makes assumptions. The biggest one is that consumers already understand the category. For example, an illustration of an animal on the front of a cereal package doesn't make an American mother think of pet food. However, when we showed Chinese moms kid cereal packaging from developed markets, they thought the packages looked like dog food. In addition, most couldn't figure out how the product was supposed to be eaten (see Figure 6.21).

Figure 6.21. Trix Packaging from the United States. Photo credit: Sheila Fitzgerald/Shutterstock

Figure 6.22. Trix back-of-pack communication from the China launch. Photo credit: Amy Hsu

The packaging from developed markets did not need to have visual cues to help explain the product because consumers from developed markets already understand the concept of breakfast cereal. Yet, even after we explained to Chinese moms that the product was in fact a breakfast food made for kids, they initially assumed that kids should eat it dry, with their hands, the way people eat potato chips or popcorn.

Our launch addressed these issues by making sure the final packaging called out the breakfast eating occasion and contained detailed instructions on how to prepare and eat the cereal. We even made sure to print photos of Chinese children enjoying breakfast cereal with a spoon and bowl on the back of the packs (see Figure 6.22 on page 136).

Using research from the wine industry, we know that consumers will pay more for a bottle of wine when it's intended for a special occasion or given as a gift.37 Gifting, in many international markets, represents a huge sales opportunity. According to Dayalan Nayager, the managing director for Diageo Global Travel business unit, gifting represents one-third of all purchases for Diageo.38 However, consumers must be able to see the quality of the product and understand its intended use, especially when buying premium-priced gifts and luxury goods.

One of the best ways to communicate a product's usage occasion is through packaging. Impressive packaging designs and aesthetics can communicate product quality and make consumers feel less price sensitive.39 In a global study on Millennials, Deloitte found that “Quality and uniqueness are the most important factors drawing Millennial consumers to luxury products.”40

Diageo commissioned award-winning Taiwanese artist Page Tsou to create four new label designs for its latest Chinese New Year Johnnie Walker Blue Label series. Tsou said, “This unique design tells the story of Johnnie Walker's Striding Man and a loyal companion as they journey around the world bringing prosperity and rejoicing in the arrival of the New Year (see Figure 6.23). The design also contains various symbols of wealth and prosperity, making this bottle extremely unique and the perfect gift to give this Chinese New Year.”41

Figure 6.23. An example of Johnnie Walker limited edition Chinese New Year gift box. Photo credit: Amy Hsu

Consumers generally prefer to pay less for essential items that they use on a daily basis. That's why most developed markets sell essential items in larger “economy” packs at a slightly reduced price (when the price is calculated on a per use basis) to reward consumers for buying more at one time. There is now research supporting that consumers are more likely to purchase essential items when even a modest (10 percent or lower) discount is given.42

Figure 6.24. Rexona sachet deodorant. Photo credit: Amy Hsu

The problem, however, is that emerging market consumers, especially in rural areas, generally have less cash on hand. This can result in higher-priced, economy-sized packaging having a negative effect on consumer demand. This is why companies like P&G and Unilever aggressively promote sachet packaging in developing rural markets as a way to lower the out-of-pocket expense of buying their brands. In India, small shampoo sachets with up to 10 ml of product make up more than 90 percent of the category's unit sales.43

In the Philippines, Unilever was able to penetrate the challenging rural market with Rexona deodorant by developing a cream version packaged in single-use sachets that cost about 10 cents each.

When Unilever employed the same strategy in India, Rexona cream became the brand's bestseller, doubling penetration nationwide to about 60 percent. The brand was even able to gain distribution in the smallest rural mom and pop shops as a result (see Figure 6.24 on page 139).44

A common exercise that focus group facilitators use when conducting brand research is to ask respondents to assign personality traits to the various brands under evaluation. For example, if a facilitator asked me to describe Apple, I would describe the brand as innovative, passionate, and contemporary. For Nike, I might say it is athletic, inspirational, and competitive.

As we know, just like brands, consumers have defining personality styles, and now research suggests that the brands we favor tend to reinforce our own style and self-image. Not surprisingly, research also suggests that a brand's personality can have a positive effect on purchase intention.45

According to David Aaker, a brand's “personality is an important dimension of brand equity because, like human personality, it is both differentiating and enduring. A brand personality can be a vehicle to express a person's self, represent relationships, and even communicate attributes.”46

It stands to reason that people from different countries have different personality styles. Several studies have found that specific personality traits are expressed more in some countries. When psychologists administered personality tests to people in different countries throughout the world, they validated that the average personality in one country is often very different from the average personality in another.47

When Millward Brown asked more than five hundred thousand consumers to describe brands using a set of twenty-four preselected adjectives to cover a wide range of personality traits, it found that consumers from different countries viewed global brands differently using their own country's cultural lens. In Spain, the Apple iPhone is perceived as sexy and desirable, in Australia an iPhone is fun and playful, and in Japan it's creative and idealistic.48

This is one of the main reasons that global shoe giants Adidas and Nike have both recently adopted mega-city strategies to fuel growth. Adidas is co-creating different styles of shoes and brand communication for each of these six major metropolitan areas: New York, Los Angeles, London, Paris, Shanghai, and Tokyo. Nike is focusing on twelve key cities for its consumer direct offense: New York, London, Shanghai, Beijing, Los Angeles, Tokyo, Paris, Berlin, Mexico City, Barcelona, Seoul, and Milan.49

In developing countries, when disposable income levels increase, it's common for consumers to become more individualistic. McKinsey & Company conducted surveys in China confirming that its consumers are now less willing to accept “one size fits all” solutions. Consumption choices are instead gravitating toward products and brands that better fit individual personalities.50

Nike is capturing share in many markets around the world with its NIKEiD platform that helps consumers customize shoes to match their individual style. In addition to its homepage, NIKEiD has 102 studios located across the globe in markets like Canada, France, England, Europe, China, and the United States where fans can access personalized design services (see Figure 6.25).

Figure 6.25. NIKEiD/Made By You, Studio, Shanghai. Photo credit: Amy Hsu

According to Ken Dice, the Global GM of NIKEiD the customization platform now generates “significant revenue and a large portion of our total e-commerce business.”51 NIKEiD permits consumers to modify more than ten different design elements with dozens of color options, names, symbols, and logos, which allows every consumer to make their pair of Nike shoes truly unique.

In the West, we hear about Millennials being a monolithic cohort that, for example, loves technology, doesn't like hierarchy, is socially conscious and prefers direct communication. Group characteristics of Millennials can vary a lot from one country to the next. INSEAD, the HEAD Foundation, and Universum studied more than sixteen thousand millennials across forty-three countries. What they found was that Millennials from different countries, even within a specific geographic region like Asia Pacific or Wester Europe, can be as different as looking at Millennials from one region to the next.52 The implication for global brand builders is that you can't rely on stereotypes. Instead, you need to dig deeper with more specificity when trying to uncover local consumer needs and perceptions.

Shiseido is a 140-year-old premium Japanese cosmetics company with the largest share of sales among Asian manufacturers. Although Shiseido has a long history and solid reputation in Japan, it has been trying for several years to change the perception that the skincare brand only caters to mature women. As CEO Masahiko Uotani stated, young “women don't have Shiseido products in their cosmetics pouches.”53

To address this concern, Shiseido launched the “recipist” brand in Japan in 2017, and sold it primarily online, targeting Millennial women (see Figure 6.26). To create this new brand, Shiseido's New Value Creation Group conducted research to better understand what Japanese Millennial women want.

Figure 6.26. Recipist, Shiseido's skincare brand that targets Millennials. Photo credit: Amy Hsu

The team began by surveying five hundred young women about their makeup purchasing habits. Then, the team selected thirty women from the group and spent an additional twenty hours with each respondent conducting in-depth interviews, visiting their homes, and observing them using their own cosmetic products.

Kanako Kawai, who was in charge of the packaging and art direction for the project, said that the team “subdivided component elements of packaging into categories such as shape of the container, shape of the cap, color, graphic design, etc., and asked subjects to select their preferences from options offered for each element. In this way, we grasped a sense of their preferences, and incorporated these into the design.”54

Using an ethnographic research style, the Shiseido team refined its understanding of the target and found that Japanese Millennial women:

Ryosuke Kuga, one of the primary designers participating in the research, said the “process of listening to the interviewees and analyzing their responses put this concept into words, and I felt as if I had gained a new sense of clarity and understanding.”55

From a graphic design perspective, you can see the unique influence that “Kawaii” has on Japanese Millennial women. Kawaii is a Japanese cultural style that incorporates bright pastel colors and childlike imagery.56 Joshua Paul Dale, a professor at Tokyo Gakugei University, writes, “Kawaii communicates the unabashed joy found in the undemanding presence of innocent, harmless, adorable things.”57

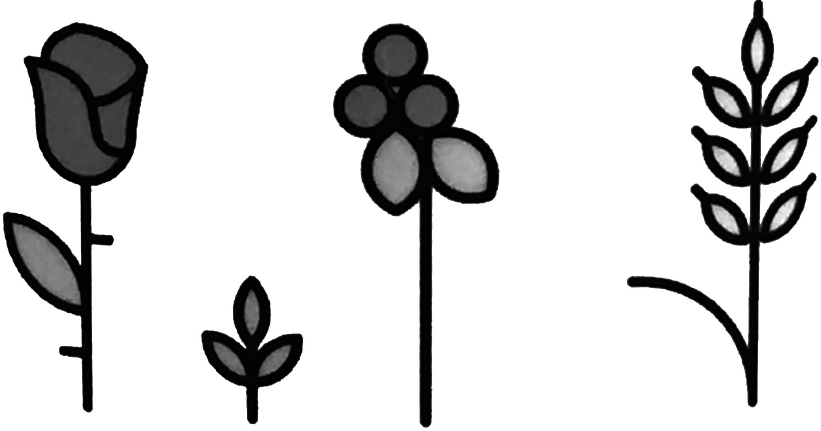

According to Shiseido's advertising and design department, “The natural pictograms that serve as a key visual element on the packaging express the natural ingredients contained in each product, such as rose extract, raspberry extract, and pearl barley extract” (see Figure 6.27). Inspired by the success of the “recipist” development process, Shiseido recently initiated a similarly structured project, but this time it is focusing on a younger target. In January 2018, the company announced the launch of POSME, a new project and brand created with the help of Japanese high school girls.58

Figure 6.27. “Recipist” pictograms. Photo credit: Amy Hsu

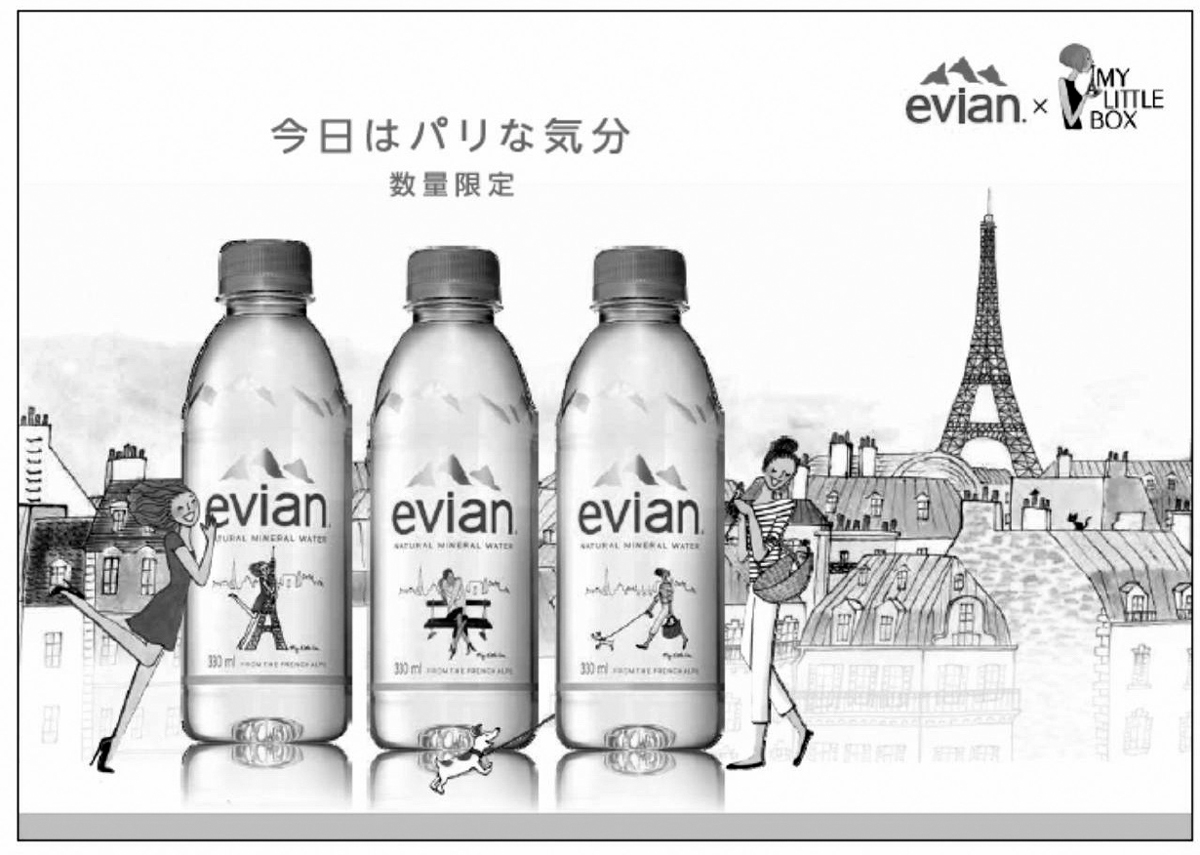

The premium mineral water category in Japan is very competitive, and many new brands enter the market each year. To increase its appeal to Millennial women, Evian began collaborating with Japanese artists to create limited edition bottles designed specifically for Japan. In 2017, the company launched its second limited collection series with “My Little Box,” a Millennial-focused brand that delivers sample boxes of cosmetics and other goods directly to Millennial women each month. The playful illustrations printed on the Evian bottles were hand drawn by Kanako, a Japanese artist/illustrator (see Figure 6.28).

To make the campaign more social, Evian introduced a meme-building site to help women create personalized “My Little Box” avatars by combining more than one hundred Kanako drawn illustrations.

Figure 6.28. The Japanese Evian “My Little Box” collaboration. Source: Danone, used with permission

The meme site enables visitors to create images that resemble themselves by customizing eight different attributes, including eyes, mouth, skin, hair, and fashion, after which they can SMS to their friends (see Figure 6.29).

Figure 6.29. An Evian Japan “My Little Box” avatar example. Photo credit: Amy Hsu, made with My Little Icon Maker site

Partnering a brand with the right celebrity can also help amplify a brand's personality. Research indicates that just announcing the use of a celebrity can increase sales by 4 percent in the immediate outcome.59 Ipsos Connect analyzed more than 2,300 ads in a pretesting database and found that ads with a star spokesperson scored higher recall and persuasiveness than ads without a celebrity spokesperson.60

In Asia, the use of Korean dramas to promote brands has been an especially powerful platform for building brand associations. Because drama series unfold over a long period of time, product placements often don't come across as paid advertisements. The key is making the link natural and believable. Ideally, the product should play a role in the storyline.

Figure 6.30. Jang Dong-gun promoting Mercedes. Photo credit: Han MyungGu/Getty Images

German automotive manufacturer Mercedes-Benz has been quite successful using Korean dramas to enhance its brand image in Korea. The brand saw increased interest in its SUV models after being prominently featured in the drama series A Gentlemen's Dignity. In that series, the main character is played by actor Jang Dong-gun. He is always expressing his affection for his car that he calls “Betty,” which sometimes even causes his girlfriend to get jealous (see Figure 6.30).61 After noticing the positive effect that the drama series had on sales, Mercedes signed Jang Dong-gun to a sponsorship deal.

Korean dramas are also very popular in Mainland China, which led Mercedes Benz to reach its highest level of sales in China after the drama My Love from the Star featured Mercedes-Benz product placement.62

Coway is a leading Korean home appliance company with a mission to make consumers' lives better by designing products that improve their quality of air, water, and sleep.

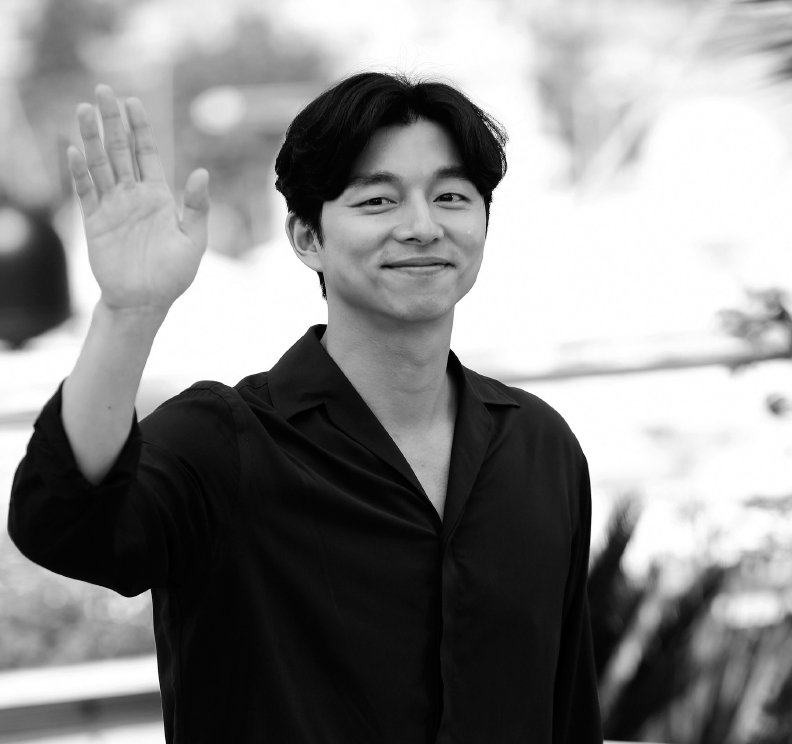

The company found itself in the middle of a product recall that had the potential to shake consumer confidence in the brand. To elevate quality and trust perceptions for the brand during this critical time, Coway launched a campaign that used Korean superstar Gong Yoo.

Figure 6.31. Gong Yoo. Photo credit: Shutterstock

Gong Yoo is a South Korean actor with a broad fan base across Asia. He became South Korea's most popular leading man after winning the Baeksang Arts Award, South Korea's equivalent of The Golden Globes (see Figure 6.31).

What makes Gong Yoo's brand especially appealing to Coway is the actor's trustworthy image within Coway's target market and direct sales force. Coway tightly linked the actor's image to a new air purifier that became the bestselling model in South Korea and Malaysia, and successfully dampened negative associations from the product recall.

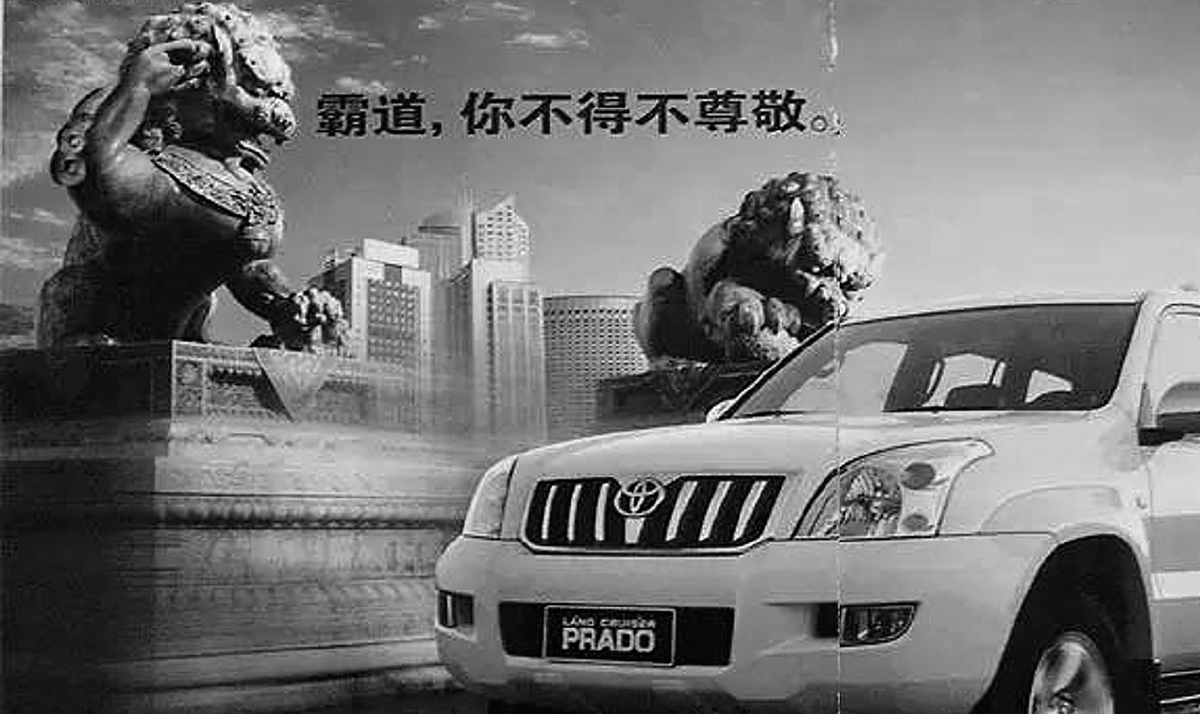

Cultural fit can be tricky to assess for anyone, especially foreigners working in an unfamiliar market. This issue made an impression on me while I was working with Saatchi and Saatchi in China during a public relations crisis that resulted from an advertisement it created for Toyota (see Figure 6.32).

Saatchi produced a print ad to promote Toyota's Prado SUV in China. The ad looks benign at first glance, but Chinese consumers quickly denounced Toyota's use of Chinese stone lions (a traditional symbol of power in China) to salute the Japanese automobile in the advertisement. Chinese consumers continue to hold negative feelings toward Japan regarding incidents from World War II. To make things worse, “Prado” was translated into “Badao” in Chinese, which means “high-handed” or “domineering.” The advertisement's Chinese tagline read: “You have to respect Badao.”

Figure 6.32. Toyota print advertisement for Prado in China. Photo credit: Amy Hsu

IKEA operates in forty-seven countries and is the world's leading furniture retailer. The brand promises “to offer a wide range of well-designed, functional home furnishing products at prices so low that as many people as possible will be able to afford them.”63 IKEA's ability to deliver on this promise is differentiating and plays a large factor in the brand's global success.

One of the brand's primary forms of communication is its famous product catalogue. The IKEA catalogue is the world's largest, distributed to two hundred million homes and read by more than five hundred million potential consumers.64 Each year, the brand creates seventy-two regional versions in thirty-two different languages. Although much of the content remains the same for each region, IKEA adapts details to cater to cultural differences.

Figure 6.33. IKEA catalogue comparison of kitchens in the United States (left) compared to China (right). Photo credit: Amy Hsu

A variety of ninja research techniques are used so the brand can gain insights to adapt to cultural needs. Prior to producing a catalogue, IKEA conducts ethnographies in every major market by visiting thousands of homes in each region to observe consumers and experience how they live. The team takes what they learned and uses the information to make adaptations to the global catalogue. Mikael Ydholm, head of research for IKEA, says, “The more far away we go from our culture, the more we need to understand, learn, and adapt.”65

Greater China is an extremely important market for the brand because eight of the world's ten largest volume IKEA stores are located there. So it's important that Chinese consumers can relate to what is pictured in the catalogue. In 2017, the Chinese catalogue team digitally modified pictures of home kitchens to more closely reflect the smaller ones typically found in Chinese homes (see Figure 6.33 on page 151).66

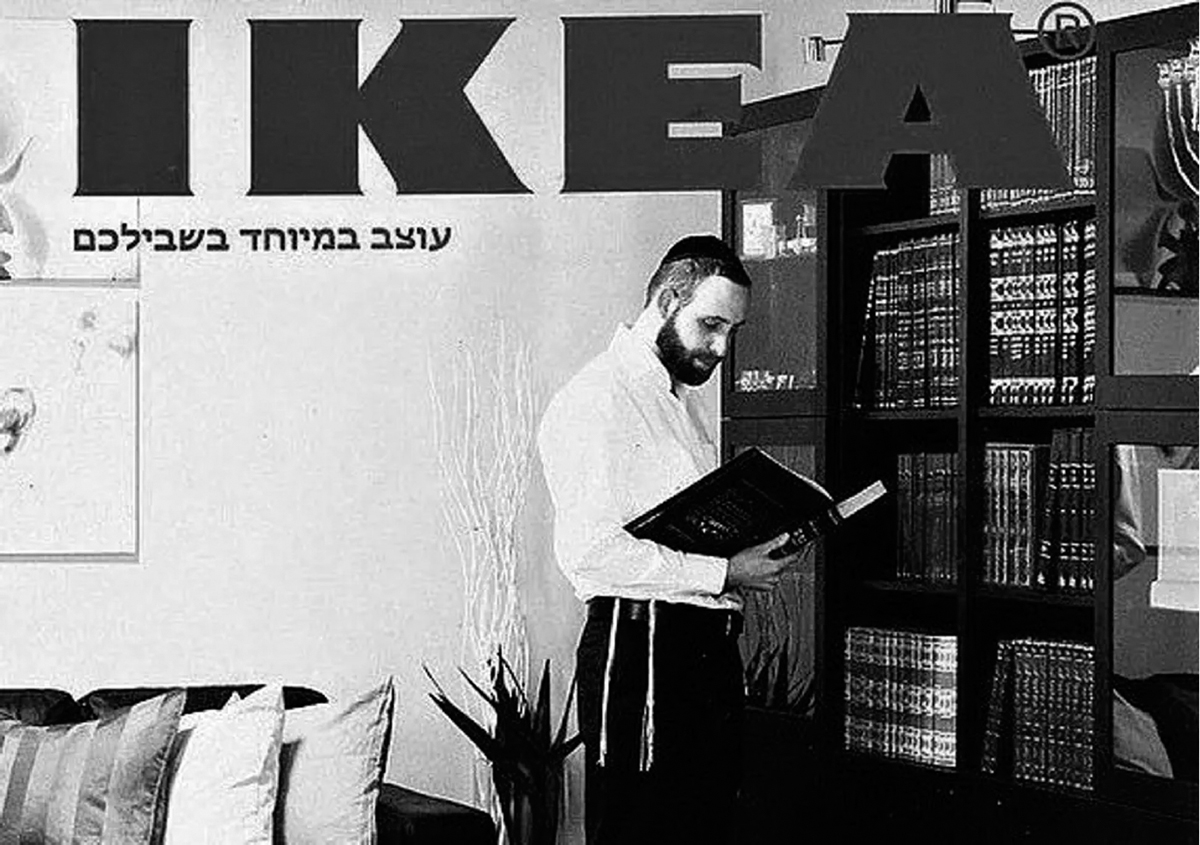

In another example of adapting to meet local cultural needs, IKEA sent members of Israel's Haredi community a catalogue with a front cover that featured challah boards, Shabbat candlesticks, Sabbath table settings, and bookcases lined with the Talmud book of Jewish civil and ceremonial law (see Figure 6.34).67

Figure 6.34. Israeli's Haredi community catalogue cover. Photo credit: Amy Hsu

When launching a global brand into a local market, make sure your brand name doesn't translate with negative connotations. This task should be at the top of your to-do list. This is best illustrated by Geoffrey James, a contributing editor for Inc.com, who created a list of the twenty worst examples of brands neglecting to take this crucial first step:

This is one of my favorite brand name adaptation stories. The Calpis brand is owned by Asahi Soft Drinks and is the leading lactobacillus beverage brand sold in Japan. Exported to more than 110 countries, the brand is especially popular with children because of its sweet yogurty flavor. According to Calpis, the name (pronounced cow-piss) is derived from “Cal,” which stands for calcium, and “pis,” which stands for salpis, a Sanskrit word that refers to milk fermentation.

In 1991, Calpis began distributing product in the United Sates. As expected, American consumers found the original Japanese name a bit unappetizing, so it was changed to Calpico to avoid confusion and negative brand associations (see Figure 6.35).

Figure 6.35. Calpico and Calpis soda. Photo credit: Amy Hsu

When entering a developing market, you first need to assess how consumers will evaluate your brand when they view it through their cultural lens. Never assume your new consumers will react the same way your consumers did back home. Not only will there be cultural differences, but the consumer care-abouts will have evolved from what was important back when the brand got its start.

Oreo cookies were first sold in the United States back in 1912. From the very beginning, Oreos were made by sandwiching rich vanilla frosting between two small round chocolate cookies. It did not take long for Oreo to become the bestselling cookie in America. For decades, even before it was the official brand slogan, Oreo cookies were known as “America's best loved cookie.”

Searching for more growth, Oreo launched into China in 1996, and believed it could just reapply what had worked so well in the United States. Unfortunately, it would not be that simple. Oreo struggled to gain momentum and even contemplated pulling out at one point. Luckily, before it failed, the team fielded consumer research to better understand local food culture and the cookie category in China.

Figure 6.36. Examples of Oreo cookies from China. Photo credit: Tang Yan Song/Shutterstock

Oreo learned that Chinese consumers were generally not that excited about the taste of the original Oreo cookie. Many thought that the filling was too sweet and that the chocolate cookie was too bitter.69 More importantly, the Oreo team learned that Chinese consumers were at a different stage in the category's lifecycle.

Chinese consumers wanted Oreos to deliver an experience in exchange for a premium price. The classic Oreo cookie just wasn't unique enough. So, Oreo reformulated its classic cookie recipe and reintroduced it with a range of new flavors that wowed consumers. Oreo's new offerings included green tea ice cream, raspberry/blueberry, mango/orange, and grape/peach. Oreo also extended the brand into the popular wafer format, which is extremely popular (see Figure 6.36 on page 156). To differentiate Oreo's offering and appeal to local needs, the brand raised the bar. Chinese Oreos combine multiple tastes and textures to provide an entertaining eating experience.

Sometimes a brand's global positioning only needs a slight adjustment to take advantage of local cultural perceptions. That was the case for Kit Kat in Japan.

Kit Kat is a British-born chocolate wafer brand owned by Nestlé. The brand got its start in England in 1937, and slowly expanded distribution to other Western markets like Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and Canada throughout the 1940s. It was during this time period that the global brand messaging coalesced around the pleasure of taking a break with Kit Kat. Kit Kat bars contain three layers of wafer that are covered with an inner and outer layer of chocolate. The original Kit Kat bar had four fingers that could be broken apart before eating.

Kit Kat arrived in Japan in 1973 with modest sales, but everything changed in 1990 when Kit Kat launched strawberry-flavored Kit Kat in Hokkaido, Japan. Hokkaido is a popular tourist destination for the Japanese, and the team was inspired to add variety to the kinds of snacks sold in Hokkaido souvenir shops. The experiment paid off as the team discovered that Kit Kat bars were perfect for gifting, because the bars are wrapped in bright, colorful single-serve packs just like traditional Japanese snacks. When the Kit Kat team began adding more Japanese-specific flavors like matcha green tea, Shinshu apple, and Hokkaido melon, sales started to take off. Kit Kat sales in Japan grew 50 percent between 2010 and 2016.70

Another adaptation that the Kit Kat Japan team made was playing on how the brand name in Japanese sounds similar to “kitto katsu,” which roughly translates into “to certainly win.”71 The Japanese brand team made the link even stronger by encouraging consumers to give Kit Kat bars to students before exams for good luck.

Nestlé's Global Head of Confectionery, Sandra Martinez, said in an interview that “Japan is the market that has made Kit Kat so iconic in terms of all the different flavors they've developed.”72 Kit Kat is now the number-one chocolate brand in Japan's $5 billion chocolate confectionery market and one of Kit Kat's largest markets globally. To date, Nestlé has launched more than three hundred different varieties of Kit Kat bars into Japan (see Figure 6.37).

Figure 6.37. Examples of Kit Kat bars from Japan. Photo credit: gnoparus/Shutterstock

Even though consumers in developing countries generally have less income than shoppers in developed markets, the price of purchasing global products in developing markets usually remains expensive because of the high costs associated with building global brands.

Too often, there is little flexibility for the global brand to adapt pricing. The question inevitably becomes: How can you build new brand associations to help increase the perceived value of your brand, so price becomes less of a barrier to trial? Because value is a function of perceived benefits and price (e.g., Value = Benefits − Price), if you cannot lower the price, you have to increase the perceived benefits.

In 1999, Starbucks opened its first Mainland China location in Beijing. As discussed in Chapter 2, Starbucks positioned itself as an experience in China. This was a smart move from a strategic perspective because it is much harder for a consumer to gauge the value of an experience versus a cup of coffee, and the experience adds perceived benefits to the cup of coffee.73

What follows is a translated radio advertisement that aired in the early days of Starbucks' launch into China. In some ways, by positioning the brand as an experience, the price of a cup of coffee becomes an entry fee to gain access to the store experience.

You can see crowded passengers out of the window, and inside, you are sharing peace and comfort with your dear coffee. We know what you want. It is the life, and love to the life. Enjoy the life, your public space, Starbucks.74

Up until today, the brand continues to build on the concept of delivering an experience as evidenced by the values statement taken from the Starbucks China website:

With our partners, coffee and customers at the core, we strive to practice the following values: Create a culture of warmth and belonging where everyone is welcome.75

Another way that Starbucks is changing its perceived value in China is by encouraging consumers to join the My Starbucks Rewards program via the WeChat payment platform, which allows those who sign up to earn “stars” that can later be redeemed for products. The WeChat payment platform seamlessly integrates with the My Starbucks Rewards program that launched in China in 2016 and already has more than twelve million users.76

Figure 6.38. WeChat Starbucks campaign in China. Photo credit: Amy Hsu

According to Belinda Wong, CEO of Starbucks China, “WeChat Pay has already reached a remarkable 29 percent of tender and has elevated the Starbucks Experience for both customers and partners through its convenience and fast transaction speed. We saw growth in all categories and day-parts” (see Figure 6.38 on page 160).77

In 2016, Tesla's China sales tripled from the previous year, which helped the company earn $1.1 billion in revenue from the China market alone.78 Tesla is managing to grow sales despite being more expensive than local electric vehicles and higher than Tesla cars sold in the United States. Because Tesla cars are manufactured in the United States, they are subject to additional costs that do not apply to locally made vehicles, such as a 10 percent sales tax, 25 percent tariff, and the extra cost of shipping a Tesla all the way from California to China.79

In response, Tesla is encouraging Chinese consumers to consider the total cost of buying and owning one of its electric vehicles. By doing this, the brand can reframe the price conversation.

Local Chinese dealerships typically inflate the list price of imported cars like BMW, Audi, and Mercedes-Benz by tens of thousands of dollars, adding various fees on top of the advertised price. Tesla's innovative direct sales showrooms do not add fees, thereby reducing the stress involved in making a new car purchase. The company also emphasizes the savings a consumer can expect to enjoy as an owner of a Tesla compared to a gasoline-fueled car during the life of the vehicle, including the benefits of having access to Tesla's easy maintenance and charging services.

Nevertheless, what's proving to be one of the most impactful factors in increasing perceived value is the differentiated image of Tesla. Like Apple stores, Tesla showrooms are modern and fun to visit compared to traditional luxury car showrooms (see Figure 6.39). Tesla has even built eighteen “experience centers” in China where schoolchildren can come on field trips to learn about science, electric vehicles, and green energy.80 The brand has been rigorously promoting its “green” positioning in China. As a result, the Tesla brand is now associated with being young, technologically savvy, and on-trend in China.

By occupying a foreign/aspirational space in the minds of consumers, Tesla has made its price point less relevant. In many ways, Tesla now finds itself competing against luxury gas-powered vehicles in China, instead of locally madeelectric-powered cars.81

Figure 6.39. Tesla showroom in a Chinese luxury shopping mall. Photo credit: Amy Hsu