just with the second) but that all three conditions are met with the first three examples.

just with the second) but that all three conditions are met with the first three examples.Equivalence Relations

In four places throughout the book we have made mention of an equivalence relation on a set. The defining properties of the construction were briefly alluded to in context but here we will look at matters in a little more detail.

First, an equivalence relation may be thought of as a generalization of ‘equals’. The universal symbolism x = y1 is replaced by something like x ~ y (x is related to y), although there is no standardization here. With equality it is evident that the two symbols either side of the equals sign are interchangeable, and so it is possible to substitute one for the other in any manipulation; the same is true in its own way with the tilde.

We must start with a set, if not of numbers then of any other well-defined objects, mathematical or not: in this explanation we shall restrict ourselves to the real numbers and subsets of them.

A partition of a set is a collection of non-overlapping subsets which together exhaust the elements of the set: equality partitions the (necessarily) distinct elements into subsets each containing a single element, the tilde partitions into subsets within each of which the elements, although not equal, may be considered in context indistinguishable from one another. Any element in any partition is, for the purposes necessary, representative of all elements in that partition.

How can a relationship defined between the elements of a set bring about a partition of that set? Let us consider some examples.

We will choose the set of integers and define a relationship between them by saying that

x ~ y if x − y is divisible by 2.

It is clear that this divides the integers into the evens and the odds; an obvious partition.

Alternatively,

x ~ y if x2 = y2

partitions the integers as {{0}, {−1, 1}, {−2, 2}, {−3, 3}, . . .}.

Finally, consider the set of real numbers with the relation defined as

x ~ y if x − y is an integer

The resulting partition of the real numbers consists of sets of numbers the decimal parts of which are equal; for example, π, π ± 1, π ± 2, . . . .

Of course, not all relationships partition; take, for example,

x ~ y if x < y.

It is in the use of the adjective equivalence that we distinguish relationships which partition from those that do not – and the adjective is justified only when three conditions are met. For all elements of the set in question:

1. x ~ x: the reflexive property;

2. if x ~ y then y ~ x: the symmetric property;

3. if x ~ y and y ~ z then x ~ z: the transitive property.

Immediately, we can see that < fails with the first two conditions (and that  just with the second) but that all three conditions are met with the first three examples.

just with the second) but that all three conditions are met with the first three examples.

It is a simple matter to show that any relation on a set which satisfies those three conditions must partition that set, and to do this we argue as follows.

Let the set be S. With the reflexive property, every element of S is contained in its own equivalence class, so all elements are accounted for. Now write the equivalence class containing x as X and suppose that X ∩ Y ≠  . If z ∈ X ∩ Y then z ~ x and z ~ y and using the reflexive property, x ~ z and z ~ y, and the transitive property x ~ y; the two equivalence classes are the same.

. If z ∈ X ∩ Y then z ~ x and z ~ y and using the reflexive property, x ~ z and z ~ y, and the transitive property x ~ y; the two equivalence classes are the same.

So, an equivalence relation partitions the set on which it is defined. Conversely, we may think of any partition of a set defining an unspecified equivalence relation with the equivalence classes precisely those partitions.

Now let us look at the detail of our use of equivalence relations.

On page 175 and ‘equivalently’ on page 223 we defined a relation on the set of real numbers by:

Two real numbers α and β are said to be equivalent if there exist integers p, q, r, s with |ps − qr| = 1 so that β = (pα + q)/(rα + s).

Let us now show that this satisfies the conditions of an equivalence relation.

1. For all α, α ~ α since α = (1α + 0)/(0α + 1) and |1 × 1 − 0 × 0| = 1.

2. If α ~ β, then β = (pα + q)/(rα + s), where |ps − qr| = 1. This means that α = (sβ − q)/(−rβ + p) and we have that |ps − (−q)(−r)| = 1. Therefore, β ~ α.

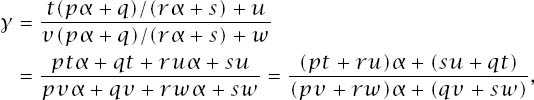

3. Finally, suppose that α ~ β and β ~  . Then, β = (pα + q)/(rα + s) and

. Then, β = (pα + q)/(rα + s) and  = (tβ + u)/(vβ + w), where |ps − qr| = 1 and |tw − uv| = 1.

= (tβ + u)/(vβ + w), where |ps − qr| = 1 and |tw − uv| = 1.

Therefore,

where

It is clear that the rational numbers occupy one class, since if β(~ α) is rational, so must be α.

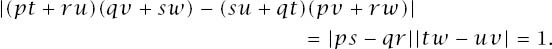

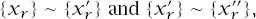

On page 243 we defined the relation between two Cauchy sequences:

Two Cauchy sequences {xr} and  are said to be equivalent (written {xr} ~

are said to be equivalent (written {xr} ~  ) if, for every rational ε > 0, there exists a positive integer N so that |xr −

) if, for every rational ε > 0, there exists a positive integer N so that |xr −  | < ε for r > N; that is, eventually their difference approaches 0.

| < ε for r > N; that is, eventually their difference approaches 0.

Figure E.1.

1. reflexivity is obvious

2. symmetry is obvious

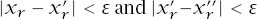

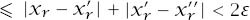

3. Suppose that  which means that

which means that  for r sufficiently large; then

for r sufficiently large; then

for r sufficiently large, and we are done.

for r sufficiently large, and we are done.

On page 248 we had defined the rational numbers as the set of equivalence classes of pairs of integers under the relation

(a, b) ~ (c, d) if and only if ad = bc.

1. For all (a, b), (a, b) ~ (a, b) since ab = ab.

2. If (a, b) ~ (c, d) then it is clear that (c, d) ~ (a, b).

3. If (a, b) ~ (c, d) and (c, d) ~ (e, f) then ad = bc and cf = de. Thus, a/b = c/d and c/d = e/f and so a/b = e/f and af = be and we are done.

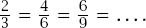

This formalizes the idea that, for example,

Finally, our interest has been with infinite sets but the concept of equivalence is meaningful if the set in question is finite and is particularly appealing if we adopt the use of partitions, suppressing the explicit use of equivalence relations. We now have a decent question to ask: How many partitions of a set of n elements are there?

If the set has just one element, S = {a}, then there is just one partition, the set itself.

If the set has two elements, S = {a, b}, then there are two partitions: ({a} {b}) and {a, b}.

n |

Bn |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

5 |

4 |

15 |

5 |

52 |

6 |

203 |

7 |

877 |

8 |

4,140 |

9 |

21,147 |

10 |

115,975 |

20 |

51,724,158,235,372 |

If the set has three elements, S = {a, b, c} there are five partitions:

({a}{b}{c}), ({a}{b c}), ({b}{a c}), ({c}{a b}), {a b c}.

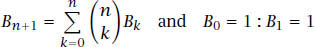

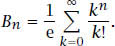

The reader may be surprised at the nature of the general formula for the number of partitions (equivalence relations) possible for a set of n elements, Bn. It is given recursively by Dobinski’s formula and defines the Bell numbers

and explicitly in terms of an irrational number

Table E.1 given the first few values of the fast increasing Bn and figure E.1 provides a logarithmic plot of a few values more.

1First recorded in The Whetstone of Witte, the 1557 publication of the Welshman Robert Recorde.