Continued Fractions Revisited

If you change the way you look at things, the things you look at change.

Max Planck

In chapter 3 we considered the application of continued fractions in the eighteenth century, as they were used to grind out the first proofs of the irrationality of e and π. Their role in the study of irrational numbers is far greater though, with a number of the results of previous chapters implicitly dependent on them; here we make some of that dependence explicit.

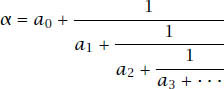

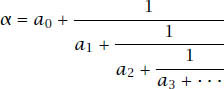

We shall continue to restrict our interest to simple continued fractions and so to finite or infinite expressions of the form

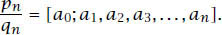

and we will adopt the notation that the nth convergent of the continued fraction is written

We will first dispose of the finite case, and in doing so rational numbers, with the following two results.

1. If two simple continued fractions are equal,

[a0; a1, a2, a3, . . . , an] = [b0; b1, b2, b3, . . . , bm],

and an, bm > 1 (a technicality needed to cope with a non-serious ambiguity in the final digit of the representation), then m = n and a1 = b1, a2 = b2, a3 = b3, . . . , an = bm.

2. A number is rational if and only if its simple continued fraction expansion is finite.

These we will not prove, but their veracity is easily established by simple proofs that are part of elementary theory and easily found.

With these we move to irrational numbers and so to the infinite continued fractions that can be used to represent them.

First, a result of Euler in the eighteenth century and Lagrange in the nineteenth combine to an important categorization, which again we choose not to prove:

The continued fraction representation of a number is periodic if and only if the number is a quadratic surd.

We discussed quadratic surds in chapter 3. Periodic continued fractions, just as with periodic decimals, are those that at some stage repeat themselves. For example,

We shall return to quadratic irrationals soon, but first we will look at the general case, wherein we have the necessarily infinite continued fraction representation of an irrational number α, without regard to any pattern in its digits.

The Hierarchy of the Convergents

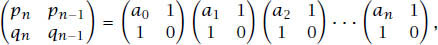

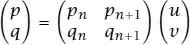

First, the continued fraction process can be conveniently represented1 using matrix multiplication in that, with our established notation,

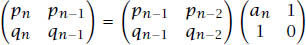

which means that

from which we can see that both numerator and denominator of the convergents are increasing with n.

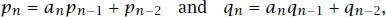

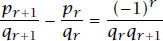

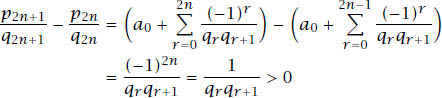

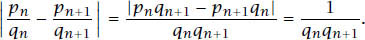

These relationships can be developed into the interrelationships between the pns and qns in that

Our interest is with the first of the two, which we will all but prove.

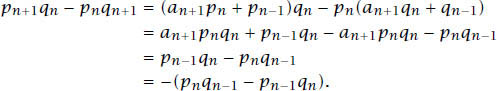

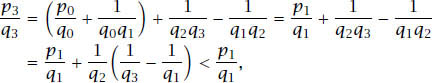

The left side, as a function of n, can write in terms of n − 1 in that

Observe now that p0 = a0, q0 = 1, p1 = a0a1 + 1, q1 = a1 and we can quickly check the initial truth of the statement and we have all we need for an inductive proof; alternatively, the use of the multiplicative nature of determinants can be utilized to give the result.

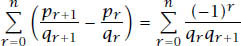

This result discloses three things:

1. The greatest common divisors,

[pn, qn] = [pn+1, pn] = [qn+1, qn] = 1.

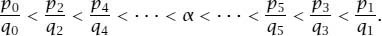

2. The form

shows that the convergents approximate α alternatively from above and below.

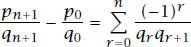

3. Adding this form gives

and the series on the left cascades to

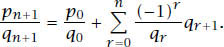

and so we have

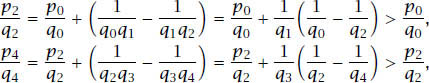

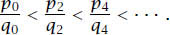

From this last, and with the qns known to be increasing, we conclude

and it is clear that we can continue this to

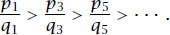

Similarly with the odd convergents

which continues to

Finally, we link the odd and the even convergents with

to get

and we have the full hierarchy

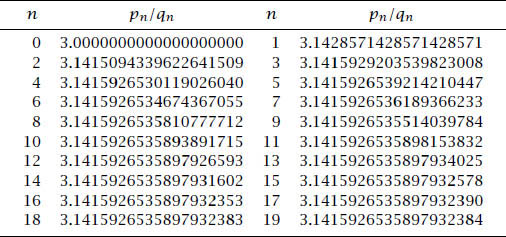

So the even-numbered convergents form a monotone increasing sequence converging to α and the odd-numbered convergents form a monotone decreasing sequence converging to α. Table 8.1 demonstrates the behaviour for α = π.

Note particularly that the path left−right−left . . . provides an oscillating sequence and that the biggest even convergent is smaller than the smallest odd convergent − and that π lies between them, as it does between every consecutive pair of them.

Rational Approximation Revisited

In chapter 6 we repeatedly pressed for ever greater accuracy of the rational approximation to a given irrational number, and we judged an approximation p/q to be better than p′/q′ provided that |qα − p| < |q′ α − p′|. As we squeezed the tolerance so we sieved the irrationals, finishing with the Lagrange Spectrum of ‘break-points’, which is intimately connected to the exotic Markov Spectrum of numbers. Our proofs were non-existential and disguised the fact that continued fractions usually lay at their heart, and we will here take the opportunity to revisit some of them, couched in this alternative language.

The convergents pn/qn are the best possible approximations to a number in the sense that if p and q are integers with q < qn+1 then |qα − p|  |qnα − pn|.

|qnα − pn|.

We will prove this and do so by assuming that, on the contrary, |qα − p| < |qnα − pn|, where q < qn+1.

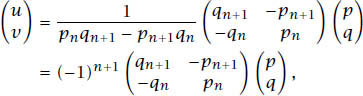

If we define the two numbers u and v by the equations

p = upn + vpn+1 and q = uqn + vqn+1.

Then u and v are integers, since,

and so

which means that

Furthermore, v ≠ 0, since if it were, p = upn, q = uqn and we would have the contradiction

Also, u ≠ 0, since if it were, q = |v|qn+1, which contradicts q < qn+1.

Further, u and v must be of opposite signs since, if v < 0 upn = p − vpn+1 ⇒ u > 0, whereas, if v > 0, q < vqn+1 ⇒ uqn < 0 ⇒ u < 0.

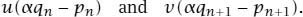

Also note that

must be of opposite signs because, from observation (3) on page 213, α lies between pn/qn and pn+1/qn+1. Combine these results to the observation that these two must have the same sign:

which is, once again, a contradiction.

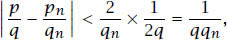

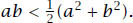

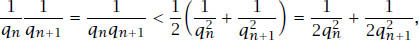

We also argued that any irrational number can be approximated so that |α−p/q| < 1/(2q2). These next two results show precisely how.

If |α − p/q| < 1/(2q2) then p/q is a convergent of the continued fraction of α.

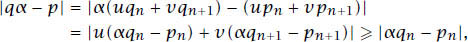

To see this, let pn/qn be some convergent of α and, with the best approximation result above, consider

Write the spectrum of denominators of the convergents of α as {q1, q2, q3, . . .} and choose n so that qn  q < qn+1, in which case, 1/q

q < qn+1, in which case, 1/q  1/qn and we have

1/qn and we have

which means that the positive integer |pqn − qpn| < 1 and so it must be that p/q = pn/qn.

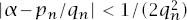

For any irrational number α, and for any two consecutive convergents, pn/qn, pn+1/qn+1 to α, either  or

or  or both.

or both.

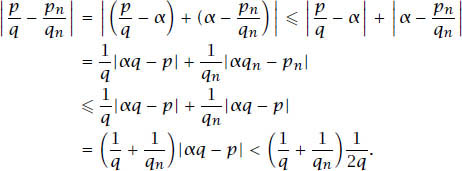

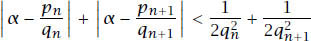

Now we have

Using the result that α lies between two consecutive convergents, we have

so

But

(a − b)2 = a2 + b2 − 2ab > 0

so

Take a = 1/qn and b = 1/qn+1, then

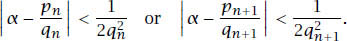

so

this means that either or both of these inequalities hold

As we pressed further we met the result of Hurwitz, which in part showed that the 2 can be increased to  . Again, the (and his) use of partial fractions reveals why, with the result:

. Again, the (and his) use of partial fractions reveals why, with the result:

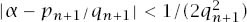

For any 3 consecutive convergents of the irrational number α, pn/qn, pn+1/qn+1, pn+2/qn+2 at least one must satisfy |α − p/q| < 1/( q2).

q2).

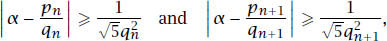

For, suppose not, then

so

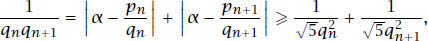

Write  = qn+1/qn and we have

= qn+1/qn and we have  + 1/

+ 1/

. Since

. Since  is rational we have

is rational we have  + 1/

+ 1/ <

<  . So,

. So,

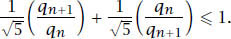

This means that  and in particular

and in particular  which makes

which makes

Write μ = qn+2/qn+1 and  . But qn+2 = an+2qn+1 + qn so qn+2/qn+1 = an+2 + qn/qn+1

. But qn+2 = an+2qn+1 + qn so qn+2/qn+1 = an+2 + qn/qn+1  1 + qn/qn+1:

1 + qn/qn+1:

A contradiction.

Now let us see how the use of continued fractions and this result of Hurwitz can be combined to give a measure of irrationality.

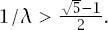

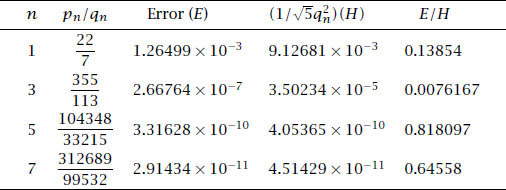

The World’s Most Irrational Number

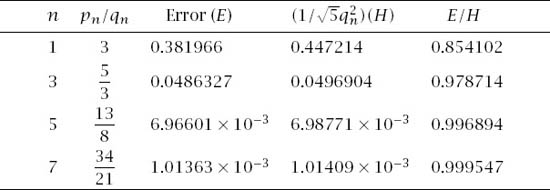

We know from this version of Hurwitz’s theorem that for every irrational number there are an infinite number of rational approximants satisfying |α − p/q| < 1/( q2) and that we should look to the continued fraction expansion of α for the best among them. Among this infinite number of ever more accurate approximants we can seek any for which the Hurwitz bound of the error is large compared with the actual error of the approximation. Consider, for example, table 8.2, which lists the first four convergents to π which are within the Hurwitz-prescribed error margin: and note the second row of data. We see that the error in the approximation

q2) and that we should look to the continued fraction expansion of α for the best among them. Among this infinite number of ever more accurate approximants we can seek any for which the Hurwitz bound of the error is large compared with the actual error of the approximation. Consider, for example, table 8.2, which lists the first four convergents to π which are within the Hurwitz-prescribed error margin: and note the second row of data. We see that the error in the approximation is far smaller than the guaranteed error margin and we can quantify this discrepancy using the ratio of the two, which appears in the final column of the table. With this we can make precise the idea one number being ‘more irrational’ than another:

is far smaller than the guaranteed error margin and we can quantify this discrepancy using the ratio of the two, which appears in the final column of the table. With this we can make precise the idea one number being ‘more irrational’ than another:

Table 8.3.

α is deemed more irrational than β if the minimum of the E/H ratio for α is greater than that for β. We judge that approximations with E/H near 0 are tighter than we might expect, whereas those near 1 are barely creeping into compliance with the Hurwitz result. Table 8.3 gives the data for e and table 8.4 that for the Golden Ratio.

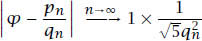

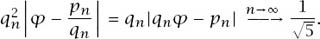

It is looking as though e might be harder to approximate than π − and that the Golden Ratio might be more resistant still, with the relative error barely keeping below the upper limit of 1 and seemingly approaching it. In the front matter we hinted that the Golden Ratio is, in fact, the most irrational number: with the stage now set, we will prove it so. To be precise we will show that, with the continued fraction approximations,

or, put another way,

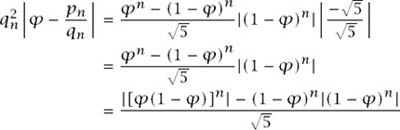

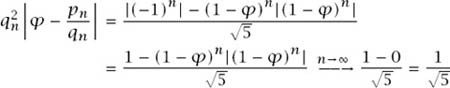

To begin the proof, we know that

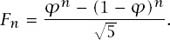

And also we know the Binet (or Euler or De Moivre) formula for the nth Fibonnaci number in terms of  :

:

Now consider

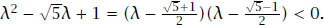

recalling that the defining equation for  is

is  2 =

2 =  + 1 we have

+ 1 we have  (1 −

(1 −  ) = −1 and so

) = −1 and so

and we are done.

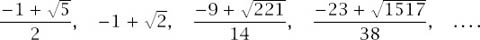

That Markov Spectrum

The second part of Hurwitz’s result showed that an essential boundary had been reached with, for example,  being incapable of being approximated to a finer tolerance; from this came the cascade of boundary irrational numbers and from them came the mysterious spectrum of numbers (and those equivalent to them) investigated by Markov. This list began

being incapable of being approximated to a finer tolerance; from this came the cascade of boundary irrational numbers and from them came the mysterious spectrum of numbers (and those equivalent to them) investigated by Markov. This list began

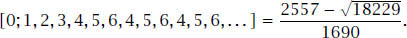

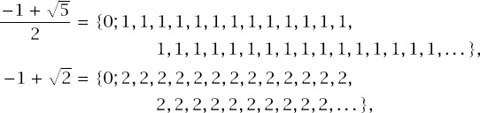

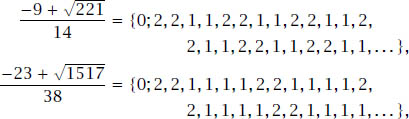

We know from an earlier result that the continued fraction form of these quadratic irrationals will be recurring; let us observe these first four:

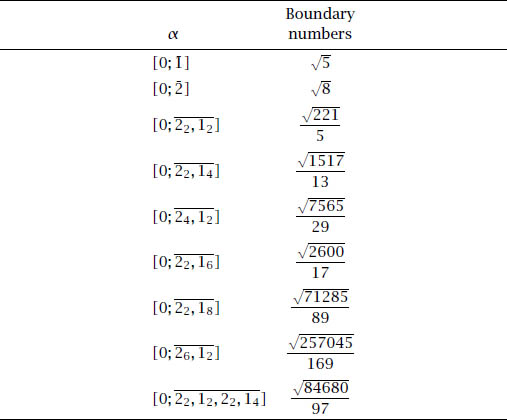

and a pattern is discerned which is absent in their surd form: periodic they certainly are, but it is this special nature of the periodicity that attracts the eye. Table 8.5 lists these and a few more in their continued fraction form, together with the associated boundary numbers of each: for brevity we adopt the standard convention that, for example, [0; 1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 1, 1, 1, 12, 2, . . . ] =  .

.

With this we are closer to the mystery of the Markov numbers but revealing it fully remains beyond our reach. We can, though, make one further incursion into the theory. The boundary numbers were not isolated but grouped into equivalence classes with the equivalence relation:2

α and α′ are equivalent if there are integers such that α′ = (aα + b)/(cα + d), where |ad − bc| = 1.

For example, the following are equivalent:

It takes but a second to notice that the last two expansions look to be identical with the first after the first few terms. In fact, the continued fraction statement is

α ~ α′ if and only if their continued fraction expansions are identical from some point on

and, in addition,

a/c and b/d are successive convergents in the continued expansion expression for α′ provided that α > 1 and c > d > 0.

For example, the list of convergents in the last case begins

There is more − much more − to expose in the study of irrational numbers through the use of continued fractions, but we hope that the reader will have gained some feeling for this most fruitful interaction. In the next chapter we will move to quite a different aspect of irrationality − for which continued fractions show a clear limitation.

1The result is susceptible to proof by induction.

2See Appendix E on page 289.