Two New Irrationals

It can be of no practical use to know that π is irrational, but if we can know, it surely would be intolerable not to know.

Ted Titchmarsh

We commented in the Introduction that “first proofs are often mirror-shy” and this chapter is devoted to two of them; neither can be placed “fairest of them all” and it is to great eighteenth-century (mathematical) kings that we look, not a wicked queen, as we gaze closely at them. In the end, it was not to be that π’s mysterious nature was first to be understood, since this occurred fully thirty years after the irrationality of e was established − a number not born in antiquity but in the eighteenth century itself. We have seen Wallis struggle with the nature of π in the last chapter; he suspected that, not only was it irrational, but that it was a new type of irrational, not definable in terms of a finite numbers of roots; its irrationality we establish here but that second quality will have to wait until chapter 7, as it had to wait for two hundred years.

As we progress our investigation into the history of irrational numbers, the theory of continued fractions is of great moment. It is through these beautiful constructions that both π and e were first proved to be irrational and, in order to understand matters, we shall need to be secure about what they are and how to construct and manipulate them: their further role is discussed in chapter 8.

Elementary Continued Fractions

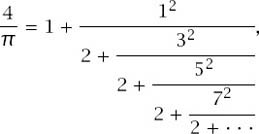

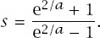

The study of continued fractions was by the eighteenth century reasonably old. The two near contemporaries from the Italian city of Bologna, Rafael Bombelli (1526–72) and Pietro Cataldi (1548–1626), had dealt with special cases but it is with the work of John Wallis that the topic began to reveal its potential. From his work others followed, with one particularly celebrated result that of the first president of the Royal Society, Lord Brouncker (1620–84), who used Wallis’s infinite product from page 90 to show that

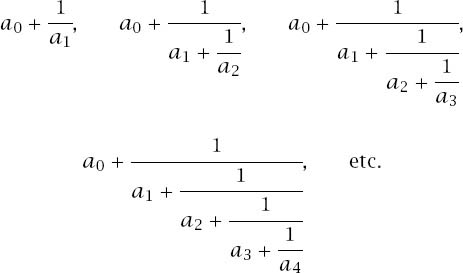

which provides us with an example of a continued fraction, that is, a number expressed in the form

where the ai, bi are integers. We shall restrict ourselves to simple continued fractions, which have the form

where the ai are positive integers.

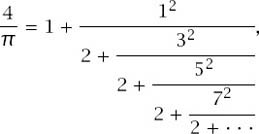

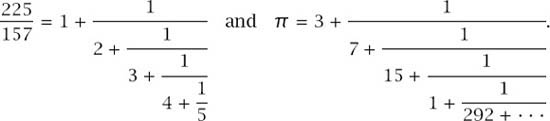

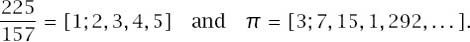

We note that the expression can be finite or infinite; for example,

Representation can be something of a typographical nightmare and, in consequence, more compact notations have been developed: principal among them is

[a0;a1, a2, a3, a4, . . .]

with the semi-colon used to separate the integer and the fractional parts of the number in question. In our two examples,

The convergents of a continued fraction are the fractions

and produce progressively more accurate approximations to the number in question. In our cases,

We should note the appearance of that most famous rational approximation to π and the remarkable accuracy of the three subsequent approximations.

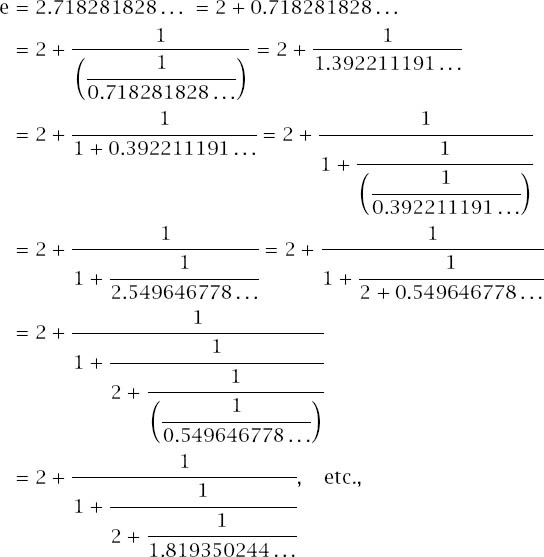

Manufacturing the convergents from the continued fraction is a matter of elementary arithmetic, as is the manufacture of the continued fraction itself from the number’s decimal expansion, as we can see from

and we have the beginning of the continued fraction of

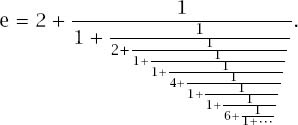

e = [2; 1, 2, 1, . . .].

In the next section we will see Euler developing his ideas from this last calculation. In the section that follows matters take a devious turn, with the continued fraction representation not of a number, but of a function.

Euler and e

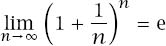

With his study of the limit

it is probable that the great Jacob Bernoulli (1654–1705) should be credited with e’s discovery but that the number is irrational must be attributed to a mathematician even greater than he. The irrationality was first recorded in a paper dated 1737 but published seven years later in the Proceedings of the National Academy of St. Petersburg.1 Its Eneström number E71 reminds us that the work is located at that position in the universally accepted index of 866 entries, compiled by Gustav Eneström of the overwhelmingly prolific eighteenth-century Swiss genius Leonhard Euler (1707–83). Euler had turned his ever-restless, ever-incisive, all-inclusive mathematical mind to the matter of continued fractions, recording his deep thoughts on the matter for the first time (although he was to return to the subject often throughout his long and incomparably impressive career2). The paper’s title is De fractionibus continuis dissertation: An essay on continued fractions. In the preamble he commented3:

Since I have been studying continued fractions for a long time, and since I have observed many important facts pertaining both to their use and their derivation, I have decided to discuss them here. Although I have not yet arrived at a complete theory, I believe that these partial results which I have found after hard work will surely contribute to further study of this subject.

In the course of its forty pages Euler touches on some basic algebraic theory as well as the far more subtle analytic implications associated with continued fractions, with the degree of hard work undertaken by him quite evident, even for someone of his remarkable calculative abilities. The paper charts a significant area of the early theory of continued fractions and we will choose a path through it that is most convenient for our purpose, which begins with an observation made in Section 11a:

The transformation of an ordinary fraction into a continued fraction with numerators all 1 and integral denominators must first be shown. Moreover, every finite fraction whose numerators and denominators are finite whole numbers may be transformed into a continued fraction of this kind which is truncated at a finite level. On the other hand, a fraction whose numerator and denominator are infinitely large numbers (which are given for irrational and transcendental quantities) will go across to a continued fraction running to infinity. To find such a continued fraction, it suffices to assign the denominators, since we set all the numerators equal to 1.

Put in other words, Euler knew that the simple continued fraction form of a rational number is finite and that of an irrational number unending. To prove e irrational he needed to manufacture such a continued fraction: the stage is set for one of his astonishing and penetrating manipulations.

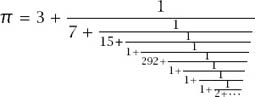

We move to sections 21 and 22 of the paper we see him turning his attention to the continued fraction form of his approximation to e ~ 2.71828182845904. These 14 decimal places would have required him to evaluate the sum  for the known infinite series expansion for e and then to perform repeatedly the process for generating the continued fraction

for the known infinite series expansion for e and then to perform repeatedly the process for generating the continued fraction

Add to this the effort required of him as he experiments with numbers related to e, as we show below, and the reader will begin to have some measure of the immense calculative ability of the man. To quote the distinguished eighteenth-century French politician and mathematician Dominique François Jean Arago:

Euler calculated without effort, just as men breathe, as eagles sustain themselves in the air.

The regular pattern of the denominators hardly escaped him and he noted that the

third denominators make up the arithmetic progression 2, 4, 6, 8, etc., the others being ones. Even if this rule is seen by observation alone, nevertheless it is reasonable to suppose that it extends to infinity. In fact, this result will be proved below.

Of course, such a proof would render e to be irrational.

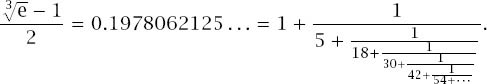

His relentless desire to experiment had him move to  = 1.6487212707 and the continued fraction

= 1.6487212707 and the continued fraction

And once again, what he describes as the interrupted arithmetic progression, is noted. These interruptions are seen to disappear, apart from a disingenuous first term, with

And to disappear altogether with

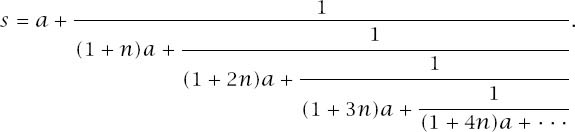

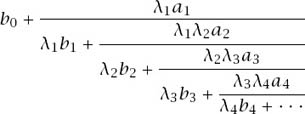

He had not reached but was homing in to the study of continued fractions having numerators 1 and denominators in arithmetic progression, which he characterized in Section 31 as

Commenting:

Furthermore, from the number e itself, whose continued fraction has an interrupted arithmetic progression of denominators, I have observed that with a few changes of this kind a continued fraction free of interruptions can be formed, For example,

Now he had manufactured an ‘uninterrupted’ arithmetic progression and one which is a special case of his general schema, with a = n = 2. (He gave no explicit decimal approximation for the number.)

In the preceding sections, where I have converted the number e (whose logarithm is 1) together with its powers into continued fractions, I have only observed the arithmetic progression of the denominators and I have not been able to affirm anything except the probability of this progression continuing to infinity. Therefore, I have exerted myself in this above all: that I might inquire into the necessity of this progression and prove it rigorously. Even this goal I have pursued in a peculiar way . . .

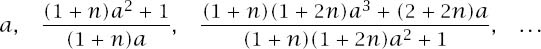

Euler’s investigation into the nature of his general arithmetic progression type of continued fraction begins with him writing out the first few convergents:

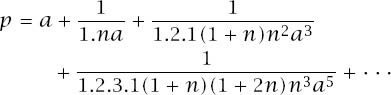

and then, using arguments from earlier in the paper, rewrites the continued fraction as the ratio of two power series

where the variables p and q are defined as

Then follows a series of remarkable changes of variable.

First, the variable z is defined by a = 1/ to give

to give

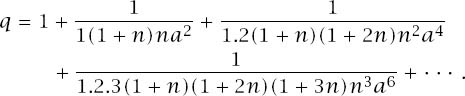

where the variables t and u are defined as

and

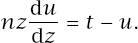

He noted that dt/dz = u and also that

We then have

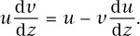

The next substitution is t = uv, thereby defining the variable v and making s = v/ .

.

Using the product and chain rules,

Now,

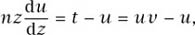

so

Substituting from above gives

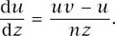

or

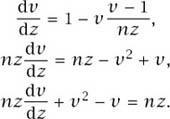

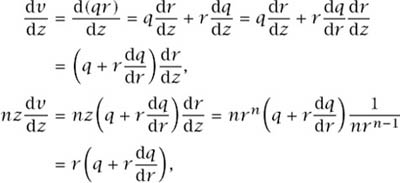

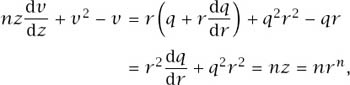

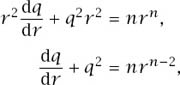

Finally, he defined r and q by z = rn and v = qr and engaged in yet more nifty calculus, which in modern form is

which makes

Expression |

Defined variable |

a = 1/ |

z |

t = numerator |

t |

u = denominator |

u |

t = uv |

v |

z = rn |

r |

v = qr |

q |

which simplifies to

from which he observed:

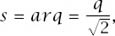

From this equation, if q may be determined from r and r is set equal to r = n−1/na−2/n then the desired value will be s = aqr.

And he comments that the differential equation

agrees with the equation once proposed by Count Riccati.

At this point the reader might benefit from a summary of the defined variables and the equations defining them, which is provided in table 3.1. In which case, as Euler observed, s = v/ = av = aqr.

= av = aqr.

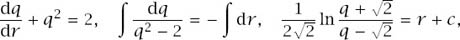

Euler had been working on a particularly difficult type of differential equation,4 which had been proposed in 1720 by the Venetian nobleman Count Jacopo Francesco Riccati (1676–1754) and somehow he had managed to transform his problem of infinite continued fractions to its solution; quite how he matched the two, we are left to wonder. He returned both to continued fractions and to the further delicate study of the Riccati Equation and to the combination of both of them5 but fortunately the situation of importance to us is n = a = 2, a special case which makes the solution of the equation easy. So,

which makes

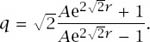

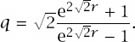

And to make v = qr always finite we have his boundary condition ‘q = ∞, r = 0’ to give A = 1 and

And finally

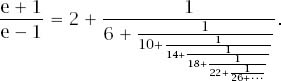

and

and  which makes

which makes

Using the fact that, in our case, a = 2, we have

The number (e + 1)/(e − 1) has an infinite arithmetic progression as its denominators in its representation as a continued fraction: therefore (e +1)/(e − 1) is irrational, therefore e is irrational. There is no such triumphant statement in E71, merely a confirmation that earlier empirical suspicions have been confirmed.

Of course, with his continued fraction form for (e2 − 1)/2 there is effectively nothing to do to prove that it and therefore e2 is irrational; a stronger result still.

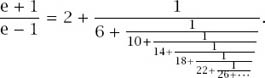

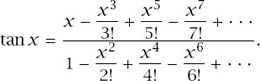

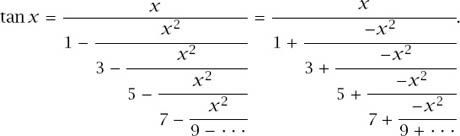

Even under Eulerian scrutiny the simple continued fraction representation of π

offered little encouragement in establishing the number’s irrationality. The nice pattern with which Euler juggled is absent, yet continued fractions do have within them the means to do the job and it was a contemporary of his, younger by 21 years, who managed (at the cost of yet more considerable effort) to be first to publish a proof. Johann Heinrich Lambert (1728–77), philosopher, physicist, geometer, probabilist and number theorist, once acolyte and friend of Euler, later antagonist to him, was to die at the age of 49. It seems remarkable today that the friendship of these two remarkable compatriots of the Berlin Academy should have been irrevocably damaged by disagreements which began with differing views on the Academy’s sale of calendars.6 Yet Lambert’s comparatively short life was spectacularly fruitful, with his 1761 proof7 that π is irrational one of its mathematical highpoints. To be more exact, he proved that, if x ≠ 0 is rational, then tan(x) is irrational: using the logical reverse of this statement, since tan(π/4) = 1 is rational, it must be that π/4 and so π is irrational.8

His proof uses a continued fraction representation not of a number but of a function, tan(x) (where x is measured in radians) and may be separated into two parts.

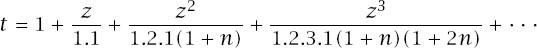

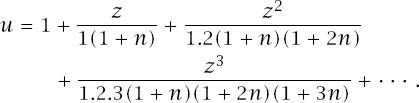

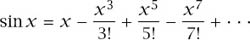

First, he needed to establish the continued fraction form of

and did so by starting with the series expansions of

and

He had, then,

The move from the ratio of two power series to the infinite continued fraction (the reverse of Euler’s approach described earlier) was achieved by a sequence of horrendous manipulations which are effectively a mixture of long division and recursion; they serve no purpose here, but the interested (patient and brave) reader is of course at liberty to pursue the details.9 This omission cuts a considerable swathe through Lambert’s involved and ingenious argument but we think the reader will judge that what follows is sufficient to impress! He had established that

The second part of the proof relies on the following two properties of continued fractions.

For the continued fraction

1. If { 1,

1,  2,

2,  3, . . .} is an infinite sequence of non-zero numbers, the continued fraction

3, . . .} is an infinite sequence of non-zero numbers, the continued fraction

has the same convergents as y and, if there is convergence, converges to y.

2. Now suppose that b0 = 0.

If |ai| < |bi| for all i  1, then:

1, then:

(a) |y|  1;

1;

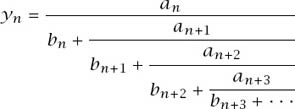

(b) writing

if, for some n and above, it is never the case that |yn| = 1, then y is irrational.

We shall not prove these here, but the interested reader is referred to Appendix C on page 281.

Now consider that continued fraction expansion for y = tanx and suppose that x = p/q. Then

And we can eliminate the denominators by using property 1 above with λi = q for all i to get

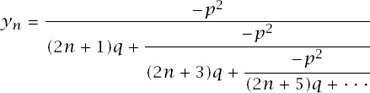

Now define yn in the manner above:

but ensure that n is so big that p2 < 2nq. This means that |−p2| < (2n + r)q for r = 1, 3, 5, . . . and this means that condition 2 above is satisfied and so |yn|  1; evidently, |yn+1|

1; evidently, |yn+1|  1 also.

1 also.

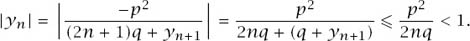

But yn = −p2/((2n + 1)q + yn+1), where the numerator is evidently negative and the denominator (2n + 1)q + yn+1 = 2nq + (q + yn+1) positive since q  1 and |yn+1|

1 and |yn+1|  1, which means that

1, which means that

So, although |yn|  1 we have |yn| < 1 and so yn ≠ ±1 for all sufficiently large n. This means that tan(p/q) is irrational. As the man himself said,

1 we have |yn| < 1 and so yn ≠ ±1 for all sufficiently large n. This means that tan(p/q) is irrational. As the man himself said,

And with these arguments we have followed in the footsteps of mathematical pioneers of the highest calibre. We have already commented that ‘first’ is seldom associated with ‘pretty’ in mathematical proof and it is often not associated with ‘rigorous’ either, particularly in earlier days. In the next chapter we will move on to more modern arguments that establish these two results and many more besides.

1Presented to the Academy on March 7, 1737.

2The interested reader may wish to consult The Euler Archive, http://math.dartmouth.edu/~euler/.

3Translation by M. F. Wyman and B. F. Wyman, 1985, Mathematical Systems Theory 18:295–328.

4E70, De constructione aequationum. Presented to the St. Petersburg Academy on February 7, 1737.

5In a paper dated 20 March 1780 and entitled E751 − Analysis facilis aequationem Riccatianam per fractionem continuam resolvendi, but which was originally published in Mémoires de l’académie des sciences de St.-Petersbourg 6:12–29 (1818).

6N. N. Bogolyubov, G. K. Mikhailov and A. P. Yushkevich (eds), 2007, Euler and Modern Science (Mathematical Association of America).

7J. H. Lambert, 1761, Mémoire sur quelques propriétés remarquables des quantités transcendentes circulaires et logarithmiques, Histoire de l’Académie Royale des Sciences et des Belles-Lettres der Berlin 17:265–322. Reprinted in 1948 in Iohannis Henrici Lambert, Opera Mathematica, Vol. II, ed. A. Speiser (Zürich: Orell Füssli).

8In the same paper and by the same means he also proved the same result for ex, using complex numbers and the continued fraction form of the function tanh(x).

9Pierre Eymard and Jean-Pierre Lafon, 2004, The Number π (American Mathematical Society).