is intercendental

is intercendentalTranscendentals

If equations are trains threading the landscape of numbers, then no train stops at pi.

Richard Preston

In the last chapter we located the country of the transcendentals without identifying any of its inhabitants: here we will discover all manner of transcendental numbers from the lowly no-names to the important such as π and e.

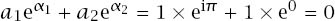

The concept of transcendence appears to date back to Leibniz since, in 1682, he discussed sinx not being an algebraic function of x (that is, it cannot be written as a finite composition of powers, multiples, sums and roots of x) and in 1704 he stated that

the number α = 21/a, a =  is intercendental

is intercendental

without, however, defining the term.

And recall the comment of John Wallis on page 91. Euler’s monumental work of 1744 Introduction to the Analysis of the Infinite has in it:

Since the logarithms of (rational) numbers which are not powers of the base are neither rational nor irrational,1 it is with justice that they are called transcendental quantities. For this reason logarithms are said to be transcendental.

and

For instance, if c denoted the circumference of a circle of radius equal to 1, c will be a transcendental quantity.

There are very many other references to this most elusive concept from these and from other mathematicians of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries: much was suspected but nothing proved.

The First Transcendental

Not until 1844 and, more conveniently stated, 1851 was a provably transcendental number exhibited and it was not π, e or any other illustrious constant but an entirely contrived number: a Liouville Number.

That d1/2/dx1/2(x) = 2 /

/ is a startling fact suggested by Leibniz in a letter to L’Hôpital dated 1695, yet the first rigorous justification of this result of the fractional calculus was provided by Joseph Liouville (1809–82) in 1832 and, in keeping with his eclectic scientific interests, included in that memoir problems in mechanics which yielded to an approach using fractional derivatives. He is also remembered for the disquieting fact that combinations of elementary functions do not necessarily possess elementary anti-derivatives; that is, integration is intrinsically hard. Liouville was at once physicist, astronomer, pure mathematician, founder and long time editor of a greatly influential mathematics magazine2 and politician. And he was the first person to provide that thing so long suspected: a transcendental number.

is a startling fact suggested by Leibniz in a letter to L’Hôpital dated 1695, yet the first rigorous justification of this result of the fractional calculus was provided by Joseph Liouville (1809–82) in 1832 and, in keeping with his eclectic scientific interests, included in that memoir problems in mechanics which yielded to an approach using fractional derivatives. He is also remembered for the disquieting fact that combinations of elementary functions do not necessarily possess elementary anti-derivatives; that is, integration is intrinsically hard. Liouville was at once physicist, astronomer, pure mathematician, founder and long time editor of a greatly influential mathematics magazine2 and politician. And he was the first person to provide that thing so long suspected: a transcendental number.

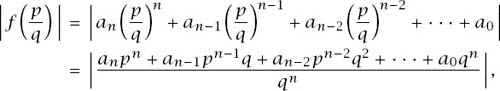

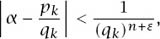

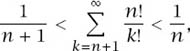

In 1844, using ideas from the theory of continued fractions, Liouville had shown how to construct transcendental numbers without explicitly exhibiting any one of them,3 but in 1851 he finally was able to produce a number which was provably transcendental4 and did so using what is now known as the Liouville Approximation Theorem. Roth’s result, of the previous chapter, was the culmination of a sequence of refinements to the result, the statement of which is:

If α is an irrational root of an irreducible polynomial

f(x) = anxn + an−1xn−1 + an−2xn−2 + · · · + a0

with integer coefficients, then for any ε > 0 there are only finitely many rational numbers p/q so that |α − p/q| < 1/qn+ε.

We see that it is a much weaker form of Roth’s result, with the tolerance dependent on the degree of the algebraic irrational’s defining polynomial. Liouville himself suspected the result was not optimal in that the power of q may well be capable of reduction. Reduced it was, stage by stage, with:

• Axel Thue (1909) reduced n to  n + 1;

n + 1;

• Carl Siegel (1921) reduced  n + 1 to 2

n + 1 to 2 ;

;

• Freeman Dyson and Aleksandr Gelfond (independently in 1947) reduced 2 to

to  .

.

And then came that ultimate result of Roth’s.

Yet, comparatively weak though the Liouville result is, it provided a necessary condition for a number to be algebraic, and therefore a sufficient condition for a number to be transcendental and, since we are in the novel position of being able to prove a general result, this we will now do.

Referring to the above statement, choose an interval(α − δ, α + δ) around α small enough to ensure that α is the only root of f(x) in that interval: if p/q is a rational approximation to α either it lies in this interval or it does not.

Suppose that it does not, then δ < |α − p/q| < 1/qn + ε and this means that q < 1/δ1/(n+ε).

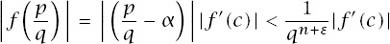

Otherwise, p/q does lie in the interval and

which means that |f(p/q)|  1/qn, yet the Mean Value Theorem5 tells us that there is a number c between α and p/q so that f(p/q) − f(α) = (p/q − α)f′(c). This means that

1/qn, yet the Mean Value Theorem5 tells us that there is a number c between α and p/q so that f(p/q) − f(α) = (p/q − α)f′(c). This means that

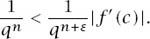

Simplifying results in q < |f′(c)|1/ε.

In both cases the integer q is bounded above and since |α − p/q| < 1 it must be that q(α − 1) < p < q(α + 1) and so for each q there are only finitely many values that p can take, resulting in only finitely many fractions p/q once again.

Liouville had the result, but how did he use it to exhibit that first transcendental number?

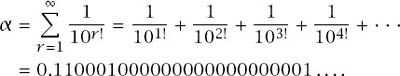

He constructed the number α as

Of course it cannot be rational since by its construction its decimal expansion is neither finite nor recurs: it is, then, irrational. Now let us more closely investigate its nature.

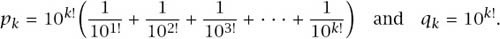

Define for k = 1, 2, 3, . . . the integers pk, qk by

Then

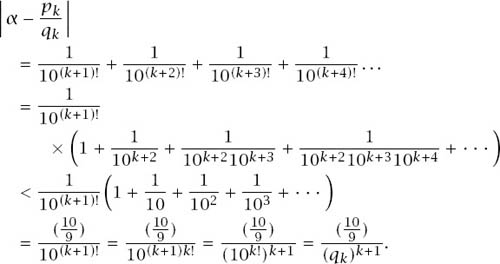

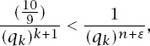

All of which means for each positive integer k

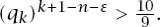

Now suppose that α is algebraic of degree n, and consider the inequality in the variable k

where ε > 0.

This solves to

No matter what value n takes, there is a minimum value of k, and all values bigger than this, such that this inequality holds and therefore such that, for these infinitely many values of k

which is a contradiction to Liouville’s theorem. If the number is not algebraic it must be transcendental.

More generally, a Liouville Number α is a number which admits the ultimate accuracy in rational approximation in that the inequality |α − p/q| < 1/qk is satisfied by infinitely many rationals p/q for all positive integers k. The Liouville Number  is just a special case.

is just a special case.

The first transcendental number had been discovered. The number was of course entirely contrived to fit with Liouville’s Approximation Theorem: it is one thing to manufacture a provably transcendental number (impressive though this feat is) but quite another to decide the nature of the important constants of mathematics such as e and π. Before we consider these great problems, we shall go back a few years to 1840 and once again to the work of Liouville, who took a tentative but elegant stride forward with e.

e, the Non-quadratic Irrational

At the end of the previous chapter we considered an important consequence of numbers which are quadratic irrationals; Liouville proved that, irrational though it is, it is not among them.

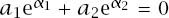

He used contradiction, as ever. So, suppose that there are integers a, b, c with a ≠ 0 for which

ae2 + be + c = 0

and rewrite the equation as

ae + be + c/e = 0.

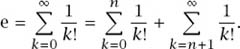

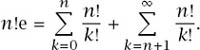

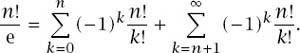

We can divide e’s canonical series expansion into two parts, the first n + 1 terms and the remainder, as we have done before, to get

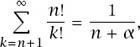

This guarantees that, when we multiply by n!, the number n!e is separated into an integer and a fractional part as

And we can find bounds for that fractional part.

On the one hand,

and, on the other,

which we can rewrite as

where 0 < α < 1.

All of this means that we can write

where I1 is an integer and 0 < α < 1.

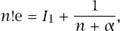

Now we repeat the process for 1/e and so n!/e, where 1/e =

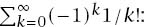

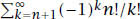

We seek a similar expression for  but matters are a touch more delicate now, with the alternating nature of the series making estimation more difficult, but we can call on the following standard result of real analysis:

but matters are a touch more delicate now, with the alternating nature of the series making estimation more difficult, but we can call on the following standard result of real analysis:

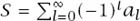

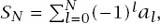

Suppose that  converges, with the {al} forming a monotonically decreasing sequence tending to 0. If the partial sums are

converges, with the {al} forming a monotonically decreasing sequence tending to 0. If the partial sums are  than SN < S < SN+1.

than SN < S < SN+1.

To utilize the result in a precise manner we will undertake the change of summation variable l = k − (n + 1) in the expression  to transform it to

to transform it to

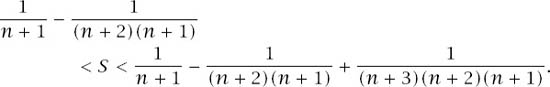

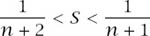

Using our quoted result above with N = 1 we have

The left-hand side is evidently 1/(n + 2) and the right bounded above by 1/(n + 1). Consequently,

making

where 0 < β < 1 and so

where 0 < β < 1.

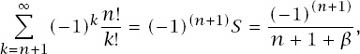

All of which means that

where I2 is an integer and 0 < β < 1.

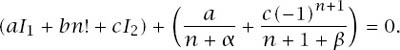

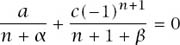

Now multiply our transformed quadratic equation by n! to get

a(n!e) + bn! + c(n!/e) = 0

and so

which we rewrite as

Since the first bracket contains an integer, so must the second. Yet we are perfectly free to choose n as we wish and, in particular, we can make it arbitrarily large, which must cause the integer

to become arbitrarily small (taking modulus if necessary); we can only conclude that it must be 0.

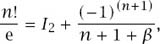

We have, then

and so,

a(n + 1 + β) + (−1)n+1c(n + α) = 0.

Since this is true for all n it must in particular be so for n = 1, 3 and this means that

a(2 + β) + c(1 + α) = 0 and a(4 + β) + c(3 + α) = 0.

Subtractions yields a + c = 0 and substitution back into the first equation (2 + β) − (1 + α) = 0 and so 1 + β = α. Since 0 < β < 1, this is a contradiction to the size restriction that 0 < α < 1.

Liouville easily extended the method to show that e2 was not a quadratic irrational but further generalization to higher powers of e and generalization to cubic irrationals and above proved elusive. The great question of the transcendence of e required new methods and it was to fall to one of Liouville’s students to provide them: Charles Hermite, whose methods set the foundations for those used much later and so effectively by Ivan Niven.

Hermite and e

In fact, in 1873, Hermite proved that er is transcendental for all rational r ≠ 0. We shall look at his remarkable argument for e alone, with the opacity of its inspiration put into suitable perspective by one of his own, and perhaps his most famous, student Henri Poincaré, who said of his teacher:

But to call Hermite a logician! Nothing can appear to me more contrary to the truth. Methods always seemed to be born in his mind in some mysterious way.

Let us look at this particular mysterious method.

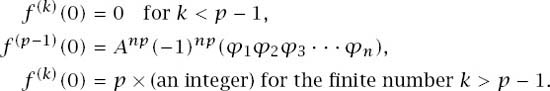

Suppose that e is algebraic, in which case it satisfies an equation of lowest degree

with integral coefficients, so a0, an ≠ 0.

This makes

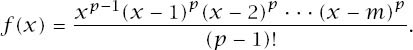

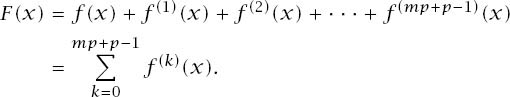

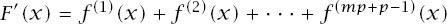

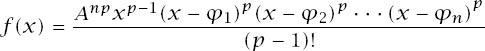

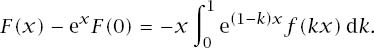

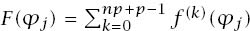

For a prime p (whose size we will later choose for our purpose) define a polynomial f(x) of degree mp+p − 1 on the interval 0 < x < m by

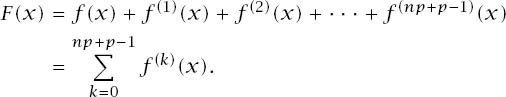

With our previously established convention that f(k)(x) = dky/dxk, now define the super-function

With f(x) a polynomial of degree mp+p − 1 evidently f(k)(x) = 0 for k > mp + p − 1 and so this stopping point in the definition of F(x) is natural.

We will look to evaluate F(x) at each integer value r = 0, 1, 2, . . . , m and will deal with two cases separately: F(r) where r > 0 and F(0).

First, consider the bracketed terms in the numerator in the definition of f(x). The only way that f(k)(r) ≠ 0 for r = 1, 2, . . . , m is when k = p, in which case there is a factor of p! in the numerator of the derivative which cancels with the (p − 1)! in the denominator to leave p in the numerator. This means that F(r) for r > 0 is an integer and has p as a factor.

Now consider f(k)(0). The only way that this is non-zero if k = p − 1, in which case, f(p−1)(0) = (−1)p · · · (−m)p and if we choose p > m we can ensure that this term, although an integer, is not divisible by p. This means that F(0) is an integer that does not have p as a factor.

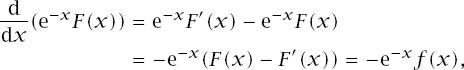

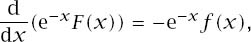

It is clear that

since the final term differentiates to 0, which means that

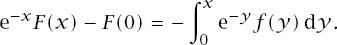

F(x) − F′(x) = f(x).

Now note that

which means that

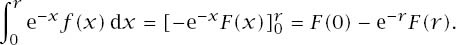

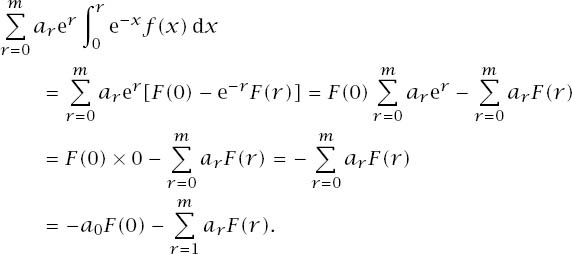

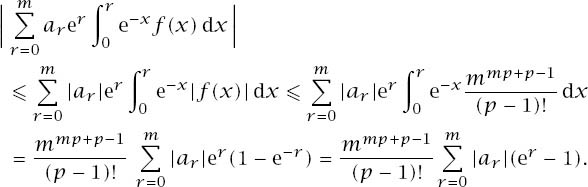

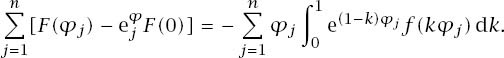

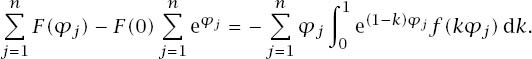

This last equation is commonly known as the Hermite Identity. Multiplying by arer and summing over r gives

We know that this final right-hand side of the equation is an integer and that the second part of it has the prime p as a common factor. We know also that p does not divide F(0) and that a0 ≠ 0, so if we ensure that p > |a0| we know that p cannot divide a0 and this makes the first part of the expression a guaranteed fraction when we divide by p, and this means that the whole expression cannot be 0. It is a non-zero integer, then, and its absolute value is  1.

1.

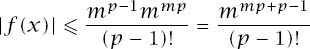

Now we look at the original left-hand side of the equation. With the bounds on x we have a gross but important upper bound on the size of f(x) with

and so,

With m fixed we can allow p to increase so that the factorial in the denominator reduces the expression to a number less than 1. This is a contradiction to the assumption that e is algebraic.

With this argument fully exposed, Poincaré’s view of his teacher is seen to be sustainable, but Hermite was quick to place a disquieting perspective on his achievement when he wrote to the German mathematician Carl Wilhelm Borchardt:

I shall risk nothing on an attempt to prove the transcendence of π. If others undertake this enterprise, no one will be happier than I in their success. But believe me, it will not fail to cost them some effort.

Lindemann and π

Hermite’s comment placed a high bounty on the mathematics necessary to establish π’s transcendence and we may suppose that he imagined the need for new techniques to achieve the purpose. We may also suppose that π had been inserted in any number of polynomial equations with integer coefficients by any number of mathematicians in the hope of achieving a contradiction. In the end, and for this purpose the end is 1882, it required only a massaging of Hermite’s own methods, one that was provided by another German, Ferdinand Lindemann (1852–1939). Whereas Hermite’s name remains attached to an impressive collection of mathematical ideas it is for this single result that Lindemann is remembered in the world of research mathematics, one that came about after consultation with Hermite himself and one that called on what is commonly held as the most beautiful formula in the whole of mathematics:

eiπ + 1 = 0.

In contrast to Lindemann, the name attached to this is attached to more mathematical and scientific ideas than any other; it is once again that Swiss genius, Leonhard Euler. Yet, it seems not to appear in this explicit form in any of Euler’s vast corpus of work and it is also true that others had stated results that imply it, but we find the expression

eiθ = cos θ + i sin θ

in his monumental text Introductio in Analysin Infinitorum of 1748, even though he had not evaluated it at θ = π.

Since i =  is algebraic (as a root of x2 + 1 = 0), it is sufficient to show that iπ is transcendental since, if π is algebraic, the closure of the algebraic numbers under multiplication would ensure that iπ is algebraic.

is algebraic (as a root of x2 + 1 = 0), it is sufficient to show that iπ is transcendental since, if π is algebraic, the closure of the algebraic numbers under multiplication would ensure that iπ is algebraic.

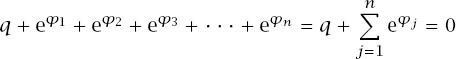

To that end, assume otherwise and let the minimum polynomial having iπ as a root also have roots α1 = iπ, α2, α3, . . . , αN, and suppose that A is its leading coefficient.

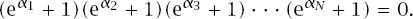

Since eiπ + 1 = 0 it must be that

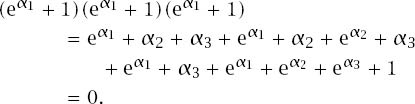

We need to multiply out these brackets and, to gain a feel for matters, let us take the case N = 3, and so generate the 23 = 8 terms

In general, we shall have 2N powers of e added together, where the powers are of the form ε1α1+ε2α2+ε3α3+ · · · +εnαn, where εr  {0, 1}. Write these powers as

{0, 1}. Write these powers as  1,

1,  2,

2,  3, . . . ,

3, . . . ,  2N. More than one might be 0 and so we will assume that the first n of them are not so, leaving q = 2N − n values which are 0. Our multiplied-out expression becomes

2N. More than one might be 0 and so we will assume that the first n of them are not so, leaving q = 2N − n values which are 0. Our multiplied-out expression becomes

We will now define our central polynomial function in much the same way as before.

Recalling that A i is an integer for i = 1, 2, 3, . . . , n the product

i is an integer for i = 1, 2, 3, . . . , n the product

(x − A 1)(x − A

1)(x − A 2)(x − A

2)(x − A 3) · · · (x − A

3) · · · (x − A n)

n)

is a polynomial with integer coefficients; so it must be

and also

where we take p to be an, as yet, unspecified prime number.

Define our polynomial function

and the super polynomial function

which makes

Making the substitution y = kx in the right hand integral we get

and so

and finally

Now evaluate this expression at each  1,

1,  2,

2,  3, . . . ,

3, . . . ,  n and add up the values to get

n and add up the values to get

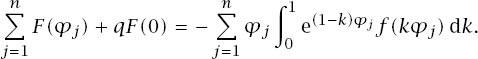

So,

And, if we recall that

we have

Let us first look at the left-hand side of the equation.

The non-zero contributions to  arise from k

arise from k  p, where the exponent p will have contributed p! to the numerator, which will cancel with the (p − 1)! in the denominator to leave p in the numerator; in short, each F(

p, where the exponent p will have contributed p! to the numerator, which will cancel with the (p − 1)! in the denominator to leave p in the numerator; in short, each F( j) is an integer divisible by p.

j) is an integer divisible by p.

Now we consider  Here we have three cases:

Here we have three cases:

In all cases we have an integer and so F(0) is an integer and if we choose p so that it does not divide A or q and sufficiently large so that it does not divide  1

1 2

2 3 · · ·

3 · · ·  n, we can ensure that p does not divide qF(0): the left-hand side of the above expression is, then, an integer which cannot be 0.

n, we can ensure that p does not divide qF(0): the left-hand side of the above expression is, then, an integer which cannot be 0.

Finally, the right-hand side is again dominated by the (p − 1)! on the bottom, with f(x) bounded in the interval [0, 1] and, as before, we can make the expression as small as we please by taking p sufficiently large. Lindemann has brought about the same contradiction as Hermite.

Elementary Observations

Populating the transcendental world beyond these hard-won examples is frustratingly difficult.

Certainly, if x ≠ 0 is algebraic and y is transcendental, then x+y and xy are transcendental: these ensure the transcendence of the likes of π +  and

and  e. But unfortunately, unlike the algebraics and like the irrationals, the transcendentals are not closed under addition and multiplication so, although we have π and e as transcendentals, the nature of the likes of π ± e, πe, π/e, πe, ππ, ee remain unknown.

e. But unfortunately, unlike the algebraics and like the irrationals, the transcendentals are not closed under addition and multiplication so, although we have π and e as transcendentals, the nature of the likes of π ± e, πe, π/e, πe, ππ, ee remain unknown.

In fact, we have no idea whether π+e and πe are even irrational but we can use a simple observation to show that at least one of them is so: the quadratic equation whose roots are π and e is x2 − (π + e)x + πe = 0 and if both π + e and πe were rational then π and e would be algebraic: we now know that they are not!

We can make other elementary observations using the closure of the algebraics to gain a little more ground: not both of π ± e can be algebraic since this would make their sum 2π algebraic and not both of πe and π/e can be algebraic since that would make their product, π2 algebraic and, with π transcendental, so must be its powers. And with this thought in mind recall that, with the Zeta function from chapter 5, ζ(2n) = Cπ2n, where C is rational: the nature of it for odd integers is a nightmare but is clearly transcendental for even integers.

The Transcendental Cascade

The above observations and others like them enable some inroads to be made into the question of the transcendence of numbers but there is one result and its sequel which stand apart in their significance. The reader may have noticed an obvious omission from the above list of combinations of e and π: eπ. It is missing because it is known to be transcendental. It is known to be transcendental because of a celebrated result known as the Gelfond Schneider Theorem and that came about in answer to a question in the most famous list of mathematical questions ever compiled.

We have mentioned German mathematical leviathan David Hilbert (1862–1943) before: in 1900 the 38 year old gave what is generally regarded as one of the most outstanding expository lectures of all time. Given at the Sorbonne in Paris at the Second International Congress of Mathematicians, the structure of The Problems of Mathematics broke from established tradition by concentrating on future mathematical challenge rather than summarizing past endeavor; at its heart is a list of 23 problems, some specific, some general, all of which he considered paramount to the future advance of mathematics, 10 of which he spoke about in his lecture. Its seductive and inspirational opening paragraph is:

Who of us would not be glad to lift the veil behind which the future lies hidden; to cast a glance at the next advances of our science and at the secrets of its development during future centuries? What particular goals will there be toward which the leading mathematical spirits of coming generations will strive? What new methods and new facts in the wide and rich field of mathematical thought will the new centuries disclose?

In his preliminary comments he drew attention to the fruitfulness of the theretofore unsuccessful attempts at proving Fermat’s Last Theorem and in 1928, in a talk given to a lay audience, he selected this great question and two of his numbered problems for comparison in difficulty: Problem 8, which is now universally known as the Riemann Hypothesis, and Problem 7, where he asked about the nature of the number 2 and more generally of αβ, where α ≠ 0, 1 is algebraic and β an algebraic irrational. Specifically, he asked whether such a number always represents a transcendental or at least an irrational number.

and more generally of αβ, where α ≠ 0, 1 is algebraic and β an algebraic irrational. Specifically, he asked whether such a number always represents a transcendental or at least an irrational number.

In that 1928 talk Hilbert expressed his belief that the Riemann Hypothesis would be resolved in his lifetime, Fermat’s Last Theorem within the lifetime of the younger members of the audience but that no one in this room will live to see a proof of the Seventh. The great man was wrong. At the time of printing, the Riemann Hypothesis remains unproved; Fermat’s Last Theorem succumbed to Andrew Wiles in 1994, when a doddery survivor of that talk could have read about that particular drama unfolding, and the Seventh Problem was to be fully resolved merely six years after the talk, in 1934. Hermann Weyl was later to refer to anyone who solved one of the 23 problems as someone who had entered the honours class of mathematicians and the names of the Russian Aleksandr Gelfond and the German Theodor Schneider were destined to be members of that most distinguished group as they, independently and simultaneously, were to provide the first complete resolution of Problem 7.

In fact, the first significant assault on Hilbert’s Problem 7 was an extension of an earlier result of Gelfond, when in 1929, the year following Hilbert’s popular talk, he established the following result:

If α ≠ 0, 1 is algebraic and β = i , where b > 0 is rational, with i2 = −1, then αβ is transcendental.

, where b > 0 is rational, with i2 = −1, then αβ is transcendental.

With this we have that 2i is transcendental. Removing i from the result fell informally to the German Carl Siegel (whose work was seminal in this and numerous other areas of number theory), but who decided not to publish his result; his magnanimous view was that Gelfond would soon see how to extend the result himself. In fact, the name of the Russian mathematician R. O. Kuzman is attached to the first appearance in print of the result in 1930, but Gelfond was to return in 1934 (along with Schneider) with the full resolution of Hilbert’s seventh problem with

is transcendental. Removing i from the result fell informally to the German Carl Siegel (whose work was seminal in this and numerous other areas of number theory), but who decided not to publish his result; his magnanimous view was that Gelfond would soon see how to extend the result himself. In fact, the name of the Russian mathematician R. O. Kuzman is attached to the first appearance in print of the result in 1930, but Gelfond was to return in 1934 (along with Schneider) with the full resolution of Hilbert’s seventh problem with

If α ≠ 0, 1 and β are algebraic, with β

, then αβ is transcendental.

, then αβ is transcendental.

Now, if we use the Euler identity eiπ + 1 = 0 we get

eπ = (eiπ)−i = (−1)−i

and we have what we need. At no extra cost we have the stronger result that the square root is transcendental too, since

Lindemann had stated but not proved a stronger result than the one he proved above, indicating that he thought it could be proved using similar ideas to those he had used. Its statement:

Given any distinct algebraic numbers α1, α2, α3, . . . , αn, if  for algebraic numbers a1, a2, a3, . . . , an then a1 = a2 = a3 = · · · = an = 0.

for algebraic numbers a1, a2, a3, . . . , an then a1 = a2 = a3 = · · · = an = 0.

It was to be his contemporary and fellow countryman, Karl Weierstrass (1815–97), who was to supply the (far from easy) proof to bring about what has become known as the Lindemann−Weierstrass Theorem and which has wide consequences:

• eα is transcendental for any non-zero algebraic number α: if eα were algebraic we could write eα = −a1/a2 for some nonzero algebraic numbers a1, a2 and so a1 + a2eα = a1e0 + a2eα = 0 and we have  , where {α1, α2} = {0, α} are two distinct algebraic numbers.

, where {α1, α2} = {0, α} are two distinct algebraic numbers.

• π is transcendental: since eiπ + 1 = 0, if iπ were algebraic we would have  for the two algebraic numbers {a1, a2} = {1, 1} and {α1, α2} = {π, 0}. Since iπ is transcendental, so must π be.

for the two algebraic numbers {a1, a2} = {1, 1} and {α1, α2} = {π, 0}. Since iπ is transcendental, so must π be.

• sinα, cos α, tan α, sinh α, cosh α, tanh α are transcendental for any non-zero algebraic number α, as are their inverse functions: these succumb through their definitions, identities and/or applications of the result. For example, we could argue that, since sin2α + cos2α = 1, if either of the two functions is algebraic the other must be and so must be cos α + i sin α = eiα and this is transcendental. Alternatively, this last identity gives sinα = (eiα − e−iα)/(2i) and so eiα − e−iα − 2i sin α = 0 and if sinα were algebraic we would have  , where {a1, a2, a3} = {1, −1, −2i sin α} and {α1, α2, α2} = {iα, −iα, 0}.

, where {a1, a2, a3} = {1, −1, −2i sin α} and {α1, α2, α2} = {iα, −iα, 0}.

In what is otherwise something of a mire of mathematical ignorance, there is something of a surprising strength of knowledge arising from this single result; more can be gained from it but with these statements we hope to have conveyed sufficient of its influence.

The Problem of Constructability

With the transcendence of π assured, not only had a highly resistant mathematical citadel been breached but the last of three geometric problems of antiquity had been resolved:

1. duplication of the cube (the Delian Problem);

2. trisection of an arbitrary angle;

3. squaring the circle.

These succinct descriptions of problems that have challenged for millennia expand to the possibility, using straight edge and compass alone, of constructing:

1. the length of the side of a cube whose volume is twice that of a given (unit) cube, and so a length  ;

;

2. the line trisecting any given angle;

3. the side of a square whose area is that of a given (unit) circle, and so a length  .

.

We will not enter into the detailed history of these problems but their antiquity and fame may be judged by the inclusion of the third in the comedy Birds, written by the Greek playwright Aristophanes and performed in 414 B.C.E.6; the plot involved the founding of a city in the sky by the main character, Peisthetaerus, with the welcome help of birds and the unwelcome intervention of some humans. One such human was the geometer Meton (who actually existed as such) and whose character, replete with straight edge and compass, offered a set of plans for the city’s design accompanied by the words:7

. . . will measure it with a straight measuring rod, having applied it, that your circle may become four-square; and in the middle of it there may be a market place, and that there may be straight roads leading to it, to the very centre . . .

to which Peisthetaerus replies:

The fellow’s a Thales!

To have squared the circle would have been a feat worthy of that great sage whom we mentioned in chapter 1.

In fact, the resolution of the three problems took around 2,200 years and took place in two parts, separated by under 50 years. With these pages strewn with a litany of famous mathematical names, Pierre Wantzel (1814–48) rather stands out, but this Frenchman owes his place here as the first person to publish proofs that the duplication of the cube and the trisection of an arbitrary angle are both impossible; also, his absence would deprive us of a character, if not a name, of note since, according to his mathematical collaborator Jean Claude Saint-Venant:

He was blameworthy for having been too rebellious to the counsels of prudence and of friendship. Ordinarily he worked evenings, not lying down until late; then he read, and took only a few hours of troubled sleep, making alternately wrong use of coffee and opium, and taking his meals at irregular hours until he was married. He put unlimited trust in his constitution, very strong by nature, which he taunted at pleasure by all sorts of abuse.

Death at the age of 34 hardly seems surprising in spite of the implied balancing effect of his wife but it is his work as a 23 year old that interests us here, for it was in 1837 that he published in that prestigious Journal de Mathématiques Pures et Appliquées, to which we have already alluded in this chapter, his analysis of the two problems − and more besides.8 Later, in 1845, he was also to give a new proof of the impossibility of solving the general quintic by radicals.

His methods, now subsumed into Galois Theory, are rather general in that they attack the wider problem of straight edge and compass constructability but our specific needs are catered for by an observation drawn from them that the cubic equation with rational coefficients

x3 + ax2 + bx + c = 0

has a root which is a constructible number9 only if it has a root which is a rational number:10 consequently, no rational roots implies no constructible roots.

The duplication of the cube requires a length of  to be constructible and this is a root of x3 − 2 = 0, which we know has no rational roots.

to be constructible and this is a root of x3 − 2 = 0, which we know has no rational roots.

The impossibility of the trisection of an angle of 60° requires the standard identity

cos 3θ = 4cos3θ − 3 cos θ

with 3θ = 60°.

Putting x = cos 20° into the equation results in

Again, there are no rational roots and so no constructible roots: cos 20° is therefore not constructible and so the angle of 60° cannot be trisected.

In passing, also in that 1837 paper, Wantzel filled a gap left by Gauss, who had famously shown that a regular p-gon can be constructed (with straight edge and compass) if p is a prime of the form  . Gauss had warned readers not to attempt the construction for primes other than these but gave no proof that this was impossible; Wantzel demonstrated that the regular heptagon is incapable of construction which, in terms of the approach above, translates to a degree 7 equation which can easily be reduced to the cubic equation

. Gauss had warned readers not to attempt the construction for primes other than these but gave no proof that this was impossible; Wantzel demonstrated that the regular heptagon is incapable of construction which, in terms of the approach above, translates to a degree 7 equation which can easily be reduced to the cubic equation

x3 + x2 − 2x − 1 = 0

with its lack of rational roots.

Wantzel’s methods did not extend to the problem of squaring the circle and nor did any others until Lindemann’s proof that π is transcendental; since all constructible numbers are algebraic, the impossibility is assured. A great and ancient problem had been solved by Lindemann and one wonders whether he found it galling to be told:

What good is your beautiful investigation regarding π? Why study such problems, since irrational numbers do not exist.

Such was the view of his influential and significant countryman Leopold Kronecker (1823–91), whose critical views were to have a destructive effect on the next contributor to the development of irrational numbers.

Cantor and Infinity

Kronecker described the German Georg Cantor (1845–1918) as a corrupter of youth and Poincaré referred to his set theory, with its transfinite numbers and all of its counterintuitive nature and paradox, a malady that would one day be cured. It would not have contributed to concord when in 1874, just a year after Hermite’s proof appeared, Cantor published a paper which showed in his precise manner that, although transcendental numbers might be fiercely elusive, there are more of them than there are algebraic numbers. To achieve this remarkable result he needed to utilize his notion of the relative sizes of infinite sets, with a countable set the smallest such and defined as one which can be put into one-to-one correspondence with  + = {1, 2, 3, . . .}: another way of describing a countable set is that it is one which can be written down as a list, with the place in the list of each element determined by that one-to-one correspondence.

+ = {1, 2, 3, . . .}: another way of describing a countable set is that it is one which can be written down as a list, with the place in the list of each element determined by that one-to-one correspondence.

If the algebraic numbers can be shown to be countable and the real numbers  not so, the complement of the algebraics in the reals must be more numerous than the algebraics themselves: there are more transcendentals than algebraics.

not so, the complement of the algebraics in the reals must be more numerous than the algebraics themselves: there are more transcendentals than algebraics.

His arguments appeared in J. De Crelle in 1874 in a paper which marked the beginning of the subject that we now know as set theory and he combined two of them to achieve the purpose. We will reproduce them in largely their original, if expanded, form.

First, the algebraic numbers are countable.

Every real algebraic number is a root of a polynomial equation with integer coefficients:

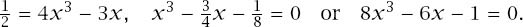

Define the height of the polynomial to be

h = n + |a1| + |a2| + |a3| + · · · + |an|,

then h  2 is an integer. Every polynomial has a height and table 7.1 lists the first few polynomials by height and also the real roots generated by them. Evidently, there are only a finite number of polynomials of any given height, each of which has only finitely many roots. This means that there are only finitely many real algebraic numbers arising from polynomials of any given height. Now we can list the algebraic numbers by the height of their defining polynomials, omitting repetition and ordering by size for each height, as below:

2 is an integer. Every polynomial has a height and table 7.1 lists the first few polynomials by height and also the real roots generated by them. Evidently, there are only a finite number of polynomials of any given height, each of which has only finitely many roots. This means that there are only finitely many real algebraic numbers arising from polynomials of any given height. Now we can list the algebraic numbers by the height of their defining polynomials, omitting repetition and ordering by size for each height, as below:

This listing of the algebraic numbers means that they must be countable. Now Cantor needed  , the set of real numbers, not to be so. His subtle approach to this allowed him at once to provide a contradiction to the assumption that

, the set of real numbers, not to be so. His subtle approach to this allowed him at once to provide a contradiction to the assumption that  is countable but also a precise method of generating irrationals and transcendentals. It relies on several intrinsic properties of any interval [α, β] of the real numbers:

is countable but also a precise method of generating irrationals and transcendentals. It relies on several intrinsic properties of any interval [α, β] of the real numbers:

• it is linearly ordered:

• it is dense: that is, between any two numbers in the interval there is another number;

• it has no gaps: that is, if it is partitioned into two nonempty sets A and B in such a way that, using the ordering, every member of A is less than every member of B, then there is a boundary point, x, so that every element less than or equal to x is in A and every element greater than x is in B.

Now we shall consider his statement and his proof of it.

Given any sequence of real numbers S and any interval [α, β] on the real line, it is possible to determine a number η in [α, β] that does not belong to S. Hence, one can determine infinitely many such numbers η in [α, β].

For, suppose that the sequence of real numbers is

S = {ω1, ω2, ω3, . . .}.

Look along S to find the first two numbers in it which lie within [α, β]; call the smaller number α1 and the larger β1. Now consider these two as endpoints of the nested interval [α1, β1] and continue along S to find the first two numbers which lie within [α1, β1]; call the smaller number α2 and the larger β2 and consider these as endpoints of the nested interval [α2, β2]. Continue the process to generate a succession of nested intervals, the endpoints of which are numbers from the sequence S. There are two possibilities: the nesting finishes after a finite number of iterations or it continues indefinitely.

Figure 7.1.

In the first case it must be that eventually it is only possible to find at most one number, ω, from S which lies in the final interval [αN, βN]: take η to be any number in [αN, βN] other than αN, βN or ω and we are guaranteed that this η does not lie in S.

In the second case there are an infinite number of nested intervals with end points each forming an infinite sequence {αn} and {βn} of numbers from S, the first increasing and bounded above (by β) and the second decreasing and bounded below (by α). Each sequence must, then, have a limit point in S, which Cantor wrote as α∞ and β∞ respectively. Once again, there are two cases:

α∞ = β∞: take η to be this common limit, which by its construction cannot be in S;

α∞ < β∞: take η to be any number in the interval [α∞, β∞], which, again by construction, cannot be in S.

In all cases we have a number in the interval [α, β] which cannot lie in the countable sequence S.

As a diagram we have figure 7.1.

Under the assumption that the real numbers are countable, take S =  and we have the contradiction that shows otherwise. Put these two last results together and we have the algebraic numbers a countable subset of the uncountable real numbers, which means that the transcendental numbers are uncountable and so ‘far more numerous’ than the algebraics.

and we have the contradiction that shows otherwise. Put these two last results together and we have the algebraic numbers a countable subset of the uncountable real numbers, which means that the transcendental numbers are uncountable and so ‘far more numerous’ than the algebraics.

Cantor’s task had been accomplished with this non-constructive argument. Yet, the argument’s essence lies with the general nature of the sequence S; it is any (infinite) sequence of real numbers and his argument shows that all such sequences lack some real number. It becomes a constructive one with his additional observation in that paper that for any sequence of algebraic numbers the case α∞ = β∞ pertains: take any such S and we are guaranteed to home in on a real number that is not contained within it.

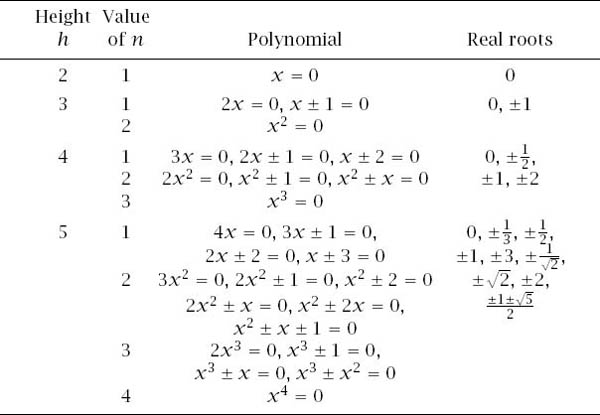

For example, if we take S to be the (countable) set of algebraic numbers his argument does not yield a contradiction, but a real number that is not a member of the sequence; that is, a number that is not algebraic − that is, a transcendental number. To suit our purpose we need an ordering of the algebraics but Cantor has provided this in his first argument and if we extract in order those (say) in the interval [0, 1] (which means that the sequence begins with  the procedure can be used to generate a transcendental number between 0 and 1. Unfortunately, the programming difficulties are great but Robert Gray11 has tackled them using a computationally more tractable method of ordering the algebraics, not by the height of the defining polynomial but by what he calls the size of the polynomial, defined using standard notation as max{n, a0, a1, a2, . . . , an}, with a secondary ordering to arrange those having the same size. The magnitude of the computational challenge is apparent from his findings that, using the previous notation,

the procedure can be used to generate a transcendental number between 0 and 1. Unfortunately, the programming difficulties are great but Robert Gray11 has tackled them using a computationally more tractable method of ordering the algebraics, not by the height of the defining polynomial but by what he calls the size of the polynomial, defined using standard notation as max{n, a0, a1, a2, . . . , an}, with a secondary ordering to arrange those having the same size. The magnitude of the computational challenge is apparent from his findings that, using the previous notation,

α7 = ω1,406,370 = 0.57341146 . . .

and

β7 = ω1,057,887 = 0.57341183 . . . .

The transcendental number being generated begins with

0.573411 . . .

and perhaps it is of interest to know that the defining polynomial equations for these two algebraic approximations are, respectively,

x6 − x5 + 2x4 + 3x3 − x2 + x − 1 = 0

and

x6 − 4x5 − x4 + 5x3 + 2x2 + 3x − 3 = 0.

Modest but, we hope, illuminating is the process applied to the rational numbers, where we will choose the convenient ordering by denominator

All rational numbers in the interval (0, 1), with some repetition, appear.

Using Cantor’s arguments, we are bound to home in on a real number between 0 and 1 that is not in the sequence; that is an irrational number. The programming task is trivial and the computational task quite manageable, yielding table 7.2. The reader will note the linkage between numerators and denominators in the αn and βn, which may be a temptation for investigation − and also that  − 1 = 0.41421356 . . . : also, sequence A084068 of the Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences12 may be of interest.

− 1 = 0.41421356 . . . : also, sequence A084068 of the Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences12 may be of interest.

A Hierarchy of (Ir)rationality

We will leave this chapter on transcendental numbers, far from its end, but with a quantitative division of the real numbers into the three types: rational, algebraic and transcendental, and also a quantitative distinction between the relative transcendence of transcendental numbers.

α |

μα |

Rational |

1 |

Algebraic |

2 |

Liouville |

∞ |

e |

2 |

π |

8.016045 . . . |

ζ(2) |

5.441243 . . . |

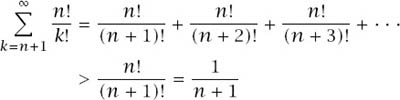

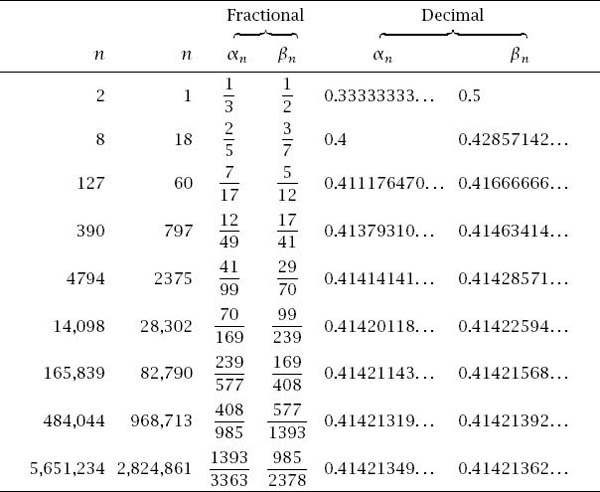

The distinction is brought about by considering the Liouville bounds on approximation in the following manner:

If we return to our generic inequality |α − p/q| < 1/qμ+ε we have seen that, if α is rational, there are only finitely many rational approximants to |α − p/q| < 1/q1+ε for any ε > 0; if α is algebraic, Roth’s result shows that there are only finitely many rational approximants to |α − p/q| < 1/q2+ε for any ε > 0. In both cases the type of number has been squeezed as far as possible in its capability of approximation. With transcendental numbers we only know that they are capable of approximation for μ  2 and it is therefore reasonable to ask for any particular number how much μ can be increased beyond 2, still with that infinite number of rational approximations.

2 and it is therefore reasonable to ask for any particular number how much μ can be increased beyond 2, still with that infinite number of rational approximations.

With such thoughts we define the irrationality measure for a given number α to be the upper bound μα of μ for which the inequality has an infinite number of solutions for any ε > 0.

The most extreme case is that of the Liouville numbers, for which μα = ∞. As we move to other numbers matters become deeply technical and very difficult. Very little is known about specific numbers and there are still fewer general theorems. Table 7.3 lists a few of the latest upper bounds at the time of going to press: notice that μe = 2 is no contradiction (algebraic ⇒ μ = 2, but μ = 2  algebraic) and that the appearance of ζ(3) is consistent with the number almost certainly being transcendental.

algebraic) and that the appearance of ζ(3) is consistent with the number almost certainly being transcendental.

A general theorem that has been established is a typically frustrating one: this last result is one of many of the Russian Aleksandr Khinchin, who gave a non-existential proof that almost all real numbers have an irrationality measure of 2. We have echoes of Cantor.

1Meaning algebraic.

2Journal de Mathématiques Pures et Appliquées.

3J. Liouville, 1844, Sur les classes très étendues de quantités dont la valeur n’est ni algébrique ni même réductible à des irrationelles algébriques, Comptes Rendus Acad. Sci. Paris 18:883–85, 910–11.

4J. Liouville, 1851, Sur des classes très-étendues de quantités dont la valeur n’est ni algébrique, ni même réductible à des irrationelles algébriques, J. Math. Pures Appl. 16:133–42.

5See Appendix F on page 294.

6At least in some translations of the work. Others would have it that there was to be a circle in a square, but we have chosen a recognized authority of stature for the translation.

7Translation by W. J. Hickie, available from Google Books at http://books.google.com/books?id=Cm4NAAAAYAAJ&source=gbs_navlinks_s.

8Pierre Wantzel, 1837, Recherche sur les moyens de reconnaître si un problème de géométrie peut se résoudre à la règle et au compas, Journal de Mathématiques Pures et Appliquées 2:366–72.

9That is, capable of being constructed with straight edge and compass.

10For a proof the reader may wish to consult, see, for example, Craig Smorynski, 2007, History of Mathematics: A Supplement (Springer).

11Robert Gray, 1994, Georg Cantor and transcendental numbers, American Mathematical Monthly 101:819–32.