Let the Game Begin: Getting to Market

So you’ve fully committed to making your idea work, and you’re now entering the blade years. You’ve come up with a plan for funding your development. Now what? I love what essayist, entrepreneur, and cofounder of seed capital firm Y Combinator Paul Graham says about how businesses get off the ground:

Startups take off because the founders make them take off. There may be a handful that just grew by themselves, but usually it takes some sort of push to get them going. A good metaphor would be the cranks that car engines had before they got electric starters. Once the engine was going, it would keep going, but there was a separate and laborious process to get it going.49

Hockey Stick Principle #22: You can’t build it and expect a market to come; you have to build your market as you build your product.

So how do you crank the engine? So much of the emphasis in writing about entrepreneurship is on crafting the product. But getting an innovative start-up up and running is as much about developing a market as about developing a product. As marketing specialist Charles Spinosa writes:

We tend to think that the inventor produces something for an already existing market and then establishes a more or less traditional company with traditional departments to produce and market the new thing. But entrepreneurs time and time again tell us that this is not the case. The market is always being developed along with the product.50

You will also need to craft your brand at this time. You might think of a brand as the name of a product, which is one meaning of the term, but it’s also used to refer to the identity and reputation a company creates in the minds of consumers. Building your brand involves not just naming your company and your products but also crafting all aspects of the look and feel of your offerings—the actual design of the product, your logo, the look of your Web site, the nature of your content marketing, the quality of your customer service operation, and the style of your advertising. In this phase of serious product development, you must be working on the product, the market, and your branding simultaneously, which makes it a very challenging time.

This is one of the biggest differences between a start-up and an established business. In established businesses, these functions are almost always divided up into separate staffs, and many even have professional product managers to monitor the progress of each group. You may be able to divide up responsibilities, especially if you have a partner, but even so, founders must keep very close tabs on product development, customer service, marketing, sales activities, and operations. Otherwise, one or another part of the process will inevitably get off track, and you’ll be working out of sync. For example, if your product prototype is all set for promoting in a crowdfunding campaign but your branding is lagging, you’ll have to postpone the campaign by a couple of months. Or you’ll be racking up lots of great preorders from retailers, but you won’t be able to fulfill in the time agreed, and retailers will start canceling them.

Juggling One Thousand Important Things at Once

How do you juggle multiple important tasks, each of which is probably equally important for success? A great product with poor packaging can flop. Great packaging or a great user experience for purchasing on your Web site can’t make up for lack of quality in the product. And a poor launch strategy and ineffective branding and pitch can lead you to believe the market isn’t interested in the product when in fact it would be with better promotion. Meanwhile, if you don’t incorporate in the optimal way and apply effectively for patents and trademarks, you might face serious tax consequences later or lose control of your branding or other intellectual property. There is no way around working on all these things at once, so you must become adept at switching tasks and adjusting your day to the unexpected while always still driving toward your goal.

Hockey Stick Principle #23: Be both rigorous in your daily planning and highly flexible about going off-plan at any moment.

As you head into your blade years, on any given day you might have to interview a new potential part-time employee, work on a product feature, provide a demo to a potential customer, discuss a future stock option plan with your attorney, write and mail checks to your suppliers, return a call from a potential angel investor who’s looking for an update about your progress, and request that your Web site developer make a number of tweaks to your landing page. And the next day could be totally different. Dealing with so many aspects of the product and business all at once is one of the most difficult parts of the whole start-up process. F. Scott Fitzgerald famously wrote, “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.” Well, the test of a first-rate entrepreneur is the ability to hold multiple streams of development in mind all at once and not go crazy or freeze up.

The process is all the more challenging because most founders have very little practical experience doing some of the required jobs. A founder who has good experience building prototypes may have little experience building a marketing platform or meeting with potential customers. Some know a lot about manufacturing but little about setting up a corporation or managing day-to-day business operations. The process can feel overwhelming.

I’ve seen this stage of development cause many founders to get stalled, putting off decisions just when they should be going full steam ahead. Some founders focus almost exclusively on the task they feel most comfortable with and badly neglect others. Some become highly agitated and begin lashing out at partners or suppliers. Many simply give up, largely due to fear and self-doubt.

The flood of advice coming at entrepreneurs during this stage can contribute to the problem. A case in point is a Forbes article that warned, “Failure to properly obtain a trademark could put your fledgling business at risk—not to mention that the time and money you have invested in establishing your business name could go to waste if someone else owns the trademark.”51 That’s sage counsel, and I’m not picking on it, but if you’ve had the paperwork on your desk for weeks to apply for a trademark for your company or product name when you read that piece, you might find yourself thinking, Oh *#@%, I’m so behind. I just don’t know what I’m doing! The trick is to accept that you’re simply not going to be able to do everything according to an optimal schedule, no matter how well you’ve anticipated what’s required and plotted a time line, while also constantly looking for better ways to get tasks done. Regarding that trademark application, a great way to go would be to hire a lawyer and offload the burden. Plus, a lawyer can normally do the work for about $1,500 and without much involvement from you.

Hockey Stick Principle #24: Building a start-up is a physical challenge as well as a mental one.

In this phase of the process, you often feel like you’re trying to control chaos; just as you’re finishing up with one thing, some new information comes in about a problem you thought you’d solved earlier, and you’ve got to switch over to attend to that. Meanwhile, your plan for the thing you had been working on goes off the rails because some negative feedback comes in, or a supplier screws up, or you find out your cost estimates were all wrong.

Even for the best multitaskers, the pace of decision making and the constant changes in your plan can be very challenging to adjust to. Anyone who’s worked a job of any level of difficulty has had to make a host of decisions every day. But the intensity of problem solving in this lead-up to the launch of a start-up, and the pressure you feel about making these decisions, can be truly fierce and badly depleting.

Psychologist Roy Baumeister has conducted fascinating studies about what’s called decision fatigue, showing that making a decision really does drain energy from your brain. His work revealed that glucose is the fuel for decision making and that each decision we make zaps our brains of some of their reserve of glucose, so the more decisions we have to make in a day, the more depleted our brains become, literally, and the quality of our decisions is compromised.52 This is why many founders will tell you that they were often exhausted much of the time as they built their companies. It doesn’t help that when you finally knock off for the day and try to get to sleep, your brain is often racing with thoughts about the decisions you’ve just made and those you’ve got to deal with the next day.

The key to surviving this crazy stage when juggling so many tasks at once is to enjoy the ride. While challenging, starting a new company will likely be one of the most memorable times of your life. To relieve stress, be disciplined about taking time for yourself and enjoying activities such as sports, yoga, hiking, traveling, good times with friends, hobbies, movies, and reading non-business books. You’ll need balance in your life because the journey is a long one.

Using Tools to Make Your Life Easier

To combat the fatigue and frustration and to get perspective on where you are and where you are heading, it’s also a good idea to make use of some of the planning, organizing, and strategizing tools developed for start-ups. The goal is to find tools you like to use that will make planning and then keeping track of the progress on all fronts more efficient. This will relieve you of some of what’s called your cognitive load, or the amount of information that you’ve got to be actively retaining in your mind at any given time. Different people prefer different tools, and some are more appropriate for some start-ups than for others. For example, if you’re building your business all by yourself, then software that facilitates efficient team communication won’t be particularly helpful. You should take a good look at the range of possibilities and check out products on their company Web site, which generally will have great tutorials and examples for how to use the tools. The main ones to know about are:

• Accounting tools: These help you manage your payables, receivables, sales, and purchases, as well as processing credit card orders and doing your payroll, all of which can be a real hassle to stay on top of otherwise. Far too many founders have lost track of bills and receipts or failed to make payments on time or to chase down a payment that’s due to come in. These systems also help to identify potential cash-flow problem areas in advance so that you can plan ahead to manage them. A great bookkeeping system is a godsend, and most of the programs require no training in accounting at all. This kind of financial software is often built specifically for your type of business—for example, for SaaS, retail, or manufacturing. Examples include Intuit’s QuickBooks, NetSuite, Cheqbook, and Xero.

• Project management tools: These facilitate planning and coordination of your development process, allowing you to create a time line that includes all parts of the process to help you create to-do lists; to make information available in one, reliable location, such as marketing copy that’s being developed and status reports; and to stay on top of the flow of tasks that are getting done and those that are coming up for completion.

These are especially helpful for keeping teams well informed and on track about what each member is working on, highlighting which deliverables are due when, facilitating efficient and transparent communication among all members of the team, and alerting you to potential problems, such as what the ripple effects would be if it were to take longer than expected for you to get your samples for a promotional event. Putting the dates for getting the samples and for the event into the system might help you consider that you need to push the date for the event back to give more wiggle room, and it might also make you think of researching a plan B venue for the event in case the original one you’ve picked won’t be available at the later date.

By creating an overview of the whole process with a schedule to accompany it, this kind of planning tool also helps you make sure you’re not overlooking tasks you’ll need to do in the future or are planning on completing either earlier or later than you should. These tools allow all members of the team to interact online, which is a great help in cutting down on the number of e-mails flying around among team members. They can also save documents, so that they’re immediately retrievable. Examples include Basecamp, Active Collab, Asana, LiquidPlanner, and Freedcamp.

• HR process management tools: Despite the fact that start-ups generally have few employees, managing the laws and complexities of payroll tax, paycheck calculations, and benefits is a confusing and time-consuming process for founders. It’s best to outsource the risks and the management of these complexities to experts, but if you can’t, these tools are up to speed with all the latest legal issues and tax provisions, which you really don’t want to be spending time digging into. Examples include ADP, Paychex, or Intuit.

Hockey Stick Principle #25: Start-up process tools do not have a brain.

Opinions are all over the map about the utility of these tools, and you should feel free to make use of the ones that appeal to you or to craft your own methods for organizing and monitoring. No matter which tools you use, you can’t expect that these programs will be doing the actual thinking or evaluation of work for you. Even if you input an exhaustive list of tasks that must be done into a project management tool, you’ll inevitably learn that you didn’t anticipate certain tasks, and you’ll have to make adjustments to the plans according to reasoning that only you can do, not a computer program. For example, you might input “critique Web site design” as a task and allocate two days in the schedule for that, but in the process of reviewing the site design, if you learn that you want to find out more about customer relationship management tools so that you make sure you’re getting the best system for that built in to your site, then you might also discover that you want to read up more on content marketing and take more time to think through your plan for that. Should you push back your schedule for getting back to your developer, or should you respond as planned and then follow up with changes? How important is it that your Web site be optimized right at the start? Maybe it’s best to go ahead with the plan as it is and make improvements later. Only you can decide.

These tools don’t solve problems for you, and you’ll still have to rigorously assess your progress in a continuous way and make all sorts of judgment calls about the issues they help to surface. But they definitely can help with lifting some of the cognitive load of managing the flow of work and communication, and they can be a huge help in thinking the logistics of the process through.

Get the Team Together

One way lots of people hope that these kinds of online planning and management tools can help is in eliminating live conversation and face-to-face meetings. Cutting down on meetings and phone calls is usually a great thing to do, but it’s important to have a certain number of face-to-face meetings and voice-to-voice calls. Meetings that bring most or all of your team together regularly, whether in person or on the phone or with video calling, can be a fantastic tool for monitoring progress, and they often stimulate discussion of issues and generation of ideas that might not have come up otherwise.

When starting First Research, I hosted a weekly conference call in which Ingo and I, and additional staff as we brought them in, simply discussed who was doing what and the kind of progress made, which worked wonderfully for us. In starting Vertical IQ, my cofounder, Bill Walker, proposed sending out a weekly update listing all the tasks in the works (normally, there were dozens of them), who was responsible for each, and the status, which we then quickly discussed. This process has also worked smoothly for that business. In both cases, we solved many problems with great efficiency. I’ve found that regularly scheduling opportunities to have actual conversations is invaluable, and I strongly advise that you don’t rely solely on electronic communication. I think we often underestimate just how efficient human conversation can be as a communication and decision-making practice. Making it work in person or over the phone just requires you to run an organized meeting by having an agenda and making sure the group sticks to it.

Working with Cofounders

The upside to having a partner or several partners is that they bring additional man power and decision-making bandwidth for coping with the controlled chaos. They usually also have complementary skills, so you can divide responsibilities in ways that make good sense, and they have the same kind of skin in the game as you. Often, they’re also willing to work without pay. The downside is that, as discussed in the last chapter, you have to share ownership, which not only affects your financial position in the company but can also make working together as a team difficult.

In 1965, Johns Hopkins University sociologist Arthur Stinchcombe published his frequently cited paper “Social Structure and Organizations,” which highlighted four common problems that cause new organizations to fail, and three of them involve interaction between founders: disagreement over dividing up financial rewards, the difficulty of determining and learning roles, and developing good working relationships. The fourth is a lack of relationships with outside parties vital to success, such as suppliers and customers.53 To overcome these challenges when working with partners, new ventures require an environment of open-mindedness, sharing of opinions, and mutual respect.

Hockey Stick Principle #26: Avoid fifty-fifty partnerships.

Clarity of decision-making responsibility and authority is also key. This is the main reason I advise against fifty-fifty partnerships. They can lead to awkward stalemates and messy negotiations. Generally speaking, I think cofounders work best together when there’s one person clearly in charge. The way to accomplish this is to have one president and for that person to own at least 51 percent of the stock. This doesn’t mean the majority owner should act like a “my way or the highway” head coach, though. If the majority owner is a bully, is selfish, and doesn’t work well with people, the organization is probably doomed; it’s that simple.

To mitigate disputes, I advise that if partners haven’t clearly divided responsibilities right at the start, they do so when heading into the serious development phase—and that the president also “own” particular responsibilities, which should be in areas of his or her greatest strength, whether that’s marketing, sales, product development, or customer service.

Note that the goal here isn’t to squelch disagreement. I believe there’s nothing wrong with heated debates between cofounders; in fact, I encourage it, and that’s often where the best solutions to problems come from. But a predetermined agreement about who has the last call is a great aid in conflict resolution.

Follow the Eighty-Twenty Rule

Another great aide to efficient decision making is the well-established principle that 20 percent of inputs generally account for 80 percent of outputs, which is based on the work of Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto, and hence is also sometimes called the Pareto Principle. Having noted that 80 percent of the land in Italy was owned by 20 percent of the population, Pareto later noted that only 20 percent of the pea pods in his garden accounted for 80 percent of the peas. The principle has been applied to business in many ways to help focus time and effort most effectively. For example, the rule holds that 20 percent of your customers account for 80 percent of your sales, that 20 percent of your products account for 80 percent of business brought in, and 20 percent of your employees account for 80 percent of your results. You can apply it to your decision making and the allocation of your time in the start-up phase, as the rule suggests that 20 percent of your decisions and 20 percent of the tasks to be completed will account for 80 percent of your results.

The concept for how to apply the rule to your business is that you should identify the most highly productive 20 percent of work processes, customers, employees, and partners and focus more of your time and attention on them. The eighty-twenty split is by no means a hard-and-fast scientific fact; you should think of it just as a general tendency and good rule of thumb for focusing your efforts.

For example, let’s say your business has one hundred customers, and you find that in fact twenty of them provide 80 percent of your revenue. I’m not suggesting that you don’t worry about providing high-quality service to your bottom eighty customers. Instead, devise a good system for providing those eighty customers with high-quality service using a standard, automated process that takes care of most of their needs very well. And for your top twenty customers, provide them a more individual, customized experience, and in addition to that, give them your proactive attention.

Another way you could apply the rule would be in prioritizing tasks to focus on every day. Most days, you will have a good ten or more key things that need to get done, and a common mistake people make in their time management is to put off harder, more consequential tasks and get a bunch of smaller, less important ones out of the way. We might do this because we’re dreading diving into the bigger tasks, perhaps due to anxiety about the outcome or because we think that if we can just cross all of those annoying smaller items off our lists, we’ll make more time to concentrate on the more important ones. For sure, we’ve got to get to the smaller tasks sometime, but tackling the most consequential ones with the greatest possible efficiency is the route to the greatest productivity. Keeping the eighty-twenty rule in mind can really help with disciplining yourself to do this.

I’ve found keeping the rule in mind is helpful in three key ways. For one, it helps me be more vigilant about focusing my time on the right tasks on my own plate and also to help those working for me to do so, as well. It also helps me not to worry so much about the other 80 percent of things I haven’t gotten to yet. And finally, it helps me make each decision faster. Indeed, some time management specialists have pointed out that the eighty-twenty rule implies that 20 percent of the time spent in making a decision accounts for 80 percent of the result. You’re never going to get your decision-making time down to that pure 20 percent, but I’ve found that keeping this concept in mind helps with not obsessing over getting more and more information and overanalyzing.

Speed of Activity versus Speed to Market

While the Lean Startup approach of getting a minimal viable product actually out to the market and in customers’ hands as fast as possible may not be right for your business, the emphasis on speed of process that’s at the heart of this approach absolutely is. Regardless of whether you start to actually sell early, it’s important that you keep up a fast pace of development and get feedback from potential customers, suppliers, and retailers early. You’ve got to stress speed of activity.

Hockey Stick Principle #27: Impatience is a virtue.

I remember watching a TV show in which Donald Trump was asked what the most important attribute he looks for in a leader is, and he said, “Impatience.” I fell out of my chair, because in entrepreneurship for sure, I’ve observed that the best leaders of the process are impatient; they are just about hell-bent to get as much done as fast as humanly possible. And by getting more done faster, they improve their chances of success for many reasons: They make more sales calls; they complete more marketing activities, such as case studies or content marketing pieces; they build more product features; and they meet with more investors.

One of the most impatient entrepreneurs I know is Darren Pierce of etailinsights, and I believe this has been key to his success. When his product team was adding a feature that involved an advanced algorithm, they had to hire a statistician to build it. Those involved in the project were getting stuck in the process and deeply analyzing each aspect of how the feature should work best for the customers, but the process of generating customer feedback and testing it was slow-going, and Darren could see that it was going to take months, which was just too long. So he halted the process and went live with the feature as it was. “I just pushed the feature live myself, and we started selling it, and our customers loved it,” Darren recalls.

You might be reading this and thinking that Darren is too quick on the draw and doesn’t often think through things well, but he does. He just understands that projects have to be completed fast enough so that the company is able to move on to the next one and allow customers to provide feedback as quickly as possible so improvements can be made.

Always keep in mind that while getting your product to market may require many months—or even years—of development, all along the way, you should be striving to accomplish each task as efficiently as possible. If you are disciplined with your time, the amount you can get done in a day may surprise you.

Delegate and Outsource

We have entered a golden era for finding part-time and contract workers. The online resources for finding talent are extraordinary, and you can reach out all the way across the country or around the world.

A very effective means of freeing up your time to focus appropriately is to identify repetitive tasks that don’t require a great deal of skill but require a great deal of time and then hire an employee at comparatively low cost to do it for you, such as a college student working as an intern (which should be a paid internship) or someone with experience but who is only looking for part-time work. This doesn’t require all sorts of paperwork; you just have to get a Form W-9, Form I-9, or a Form 1099 and a standard employment or consulting agreement from anyone you’re going to be paying. The nice thing is that part-time interns will often come aboard for ten to fifteen dollars an hour just for the experience of working at a start-up. So for ten hours a week, you pay only about $150 and free yourself up to use those ten hours for much more productive development work. It’s not often in business that you can count on getting such a great return on an investment.

Hockey Stick Principle #28: Allow others to solve your big challenges.

You should also consider all opportunities to outsource jobs. The fact that lots of programmers are available to help build software and Web sites and lots of marketing firms offer brand development, publicity, and advertising services is well known. But there are independent contractors in all other sorts of fields. The Boogie Wipes founders Julie Pickens and Mindee Doney knew very little about the chemistry required to produce their wipes. They easily found a chemist to work with to develop them, and he was right in their community. Graham Snyder found highly qualified engineers to develop his device. With First Research, neither Ingo nor I had the time to edit our research reports, so we lined up a professional outside editor to do it for us.

The rule I recommend is that you first outsource the functions that are critical to your success and that you or your cofounders have no skills in, and if you have the funds, you might also consider outsourcing work that you do have some expertise in because you have the network to find high-quality people and the skills with which to evaluate their work efficiently. For example, if you worked in branding, maybe you could decide to hire a firm to create your logo and a set of taglines to choose from so that you could focus more time on a critical function that only you can take charge of. If a function is critical to success and will require constant attention and pull too much of your time away from other equally important parts of the business, you might consider bringing in another cofounder or employee to perform the function. You might also consider offering stock options as well as pay to outside specialists you contract with for this work, as that means they’re also vested in a positive outcome. But remember, make sure your stock option plan has a vesting schedule that stipulates a duration of time the person must work for the company before the shares offered actually benefit them. That way, if these employees or consultants quit working for you prematurely, they’re not taking part of your company with them.

If you can afford it, I also recommend you consider outsourcing noncore business functions to create administrative efficiencies for your business. Examples could include managing the day-to-day accounting duties, such as check-writing and booking sales, payroll processing, inventory record management, and booking travel.

It’s often best to seek small shops with talented, innovative people and low overhead. I mostly find partners through word of mouth—asking people whom they know with a particular skill. I recommend this approach over searching online, but plenty of founders have had success with the latter. Julie and Mindee found their chemist that way. In all cases, it’s critical to have a lawyer-prepared “work for hire” contract signed, and in many cases also a noncompete letter. If you’re contracting for software code, also make sure you can take the code with you in case you have to switch to working with a different programming firm, which is not uncommon. You should also make sure contract workers have their own insurance and provide you with a certificate of coverage; otherwise, make sure your own policy covers contractors. You don’t want one freak accident to take down your entire new venture.

Smaller companies are often much more personal and easier to work with than large ones. Partners who work with your business consistently can become part of the family if cultures are shared and the passion is there. To reinforce this sense of team commitment, I give stock options to partners critical to our success. For example, Vertical IQ delivers our product via the Web, but neither Bill nor I have skill in database programming, so we hired a programmer and gave him stock options.

The value that the right outside talent can bring to your business can make an enormous difference in your outcome. One example of this is the striking bottle designs that the founders of Method ended up with. Cofounders Eric Ryan and Adam Lowry had determined that to differentiate their soaps, they needed truly striking packaging, and Eric was a big fan of top product designer Karim Rashid, who has many designs in museum collections. They wrote him an impassioned letter, telling him that “the design goal is to reinvent the banal dish soap that looks like a relic of the 1950s and sits on every sink across the landscape of America. We want you to approach it not as a packaging assignment but from a product perspective to create an object for the kitchen that is as iconic as a salt and pepper shaker.” Rashid found that mission intriguing, and he agreed to sign on as their chief creative officer, designing a stunning series of bottles that opened the door to a big order from Target and connected powerfully with customers.54

Of course, this process doesn’t always go so smoothly. Lots of people will tell you horror stories, like the Revel Systems founders, who invested their savings into getting their first iPad stand built only to have it fall far short of the mark. They then had to go into overdrive and spend more of their tight budget on another source for creating the stand. Doug Lebda’s first attempt at outsourcing the programming for LendingTree resulted in software that didn’t work at all. But don’t let these stories discourage you; just expect that some such setbacks will happen for you too, and plan on working your way through them.

Hockey Stick Principle #29: Screwups happen; let go of them and move on quickly.

Redos and tweaking are also almost always required for every piece of work you have done. So communicate clearly to contractors at the outset that you expect the project to be iterative, with possibly more than one round of changes being required, and ensure that they agree to that process. There’s an inherent conflict between your interests and theirs in this regard. The goal of every independent contractor is to get the work for you done and to move on to the next project as efficiently as possible. Your goal is often quite the opposite. You will want to tweak and revise until you’re confident the quality of the product is the best it can be. In the eyes of the contracted firm, you’re disorganized, changing your mind constantly, dragging the project out, and all this “redoing” isn’t worth the money. This is another reason that going to a smaller, often one-person shop is preferred; they generally take a more artisanal approach to their work and tend to better appreciate that you do, as well.

In addition to the obvious questions, such as whether or not you can afford to outsource a task, here are some others to consider when deciding whether to outsource something or do it yourself.

• How much time would this project require if I did it myself? Can I leverage this time more effectively doing something else?

• Might it be more effective to ask a consultant to train me so I can complete the task myself?

• Is this task absolutely necessary to get this business off the ground? Or, alternatively, could I table this task and get more feedback first?

• Is the amount of money I’m paying for this task a good return on investment? Or, alternatively, should I look at outsourcing a different project that could get a larger return on investment?

Don’t let the anxiety about handing off some of the process to others stop you. Most founders find working with a new person or firm can be really rewarding and sometimes a great deal of fun, which can counteract some of the inevitable frustrations.

From Concept to Store Shelves in Less Than a Year

Two founders who became deeply engrossed in all the details of getting their business off the ground and very smartly developed their market along with their product are Julie Pickens and Mindee Doney of Boogie Wipes. They also managed to get the work done fast, working on all fronts at once. They’re a great model of planning effectively and managing for efficiency. Even though they were developing a consumer-goods manufactured product, they got to market within a year.

The idea for their product was first conceived in February of 2007; they then incorporated that May as Little Busy Bodies, Inc., and in December, they sold their first pack of wipes. Because of good product development, strong marketing, and good retail distribution, they hit $1 million in sales their first year.

A big emphasis was on getting early versions of wipes made and then testing them with potential customers. One of the keys to the success of the product was making the wipes with the proper amount of saline, which required skills neither Julie nor Mindee had. They also had no connections to find someone with the relevant experience. So they searched online, and they found a chemist in Portland to help them.

There were several challenges with finding the right combination of saline and cloth to make for a perfect product. “You’re putting a wet wipe on your nose to wipe a wet nose,” Julie explains. “The wipe has to be wet enough to deliver the saline, but still have some absorbent capacity in it because you’re still wiping your nose.” Another product design challenge was getting the right amount of saline to work “with your body” to be effective and ensuring the saline and cloth combination didn’t have abrasive qualities. “It was tricky to get all that right,” Julie recalls. “We were very hands-on. We learned every aspect of the business as we went and were very involved in every piece of it. As we started to evolve the wipe’s [design] with the chemist, we learned all about it and started testing and doing different things and putting different things together to see if it would work, and we were very instrumental in creating the actual product itself.”

Developing samples allowed them to get market feedback from very early on. In their case, they were sure of who their market was: moms. And, as covered earlier, they first socialized the concept and tested their product name on blogs popular with mothers. Having received good feedback, they moved forward quickly with developing their branding, intent on creating desirable packaging. Maintaining a low budget, they hired a local freelance graphic designer in Portland. The outcome was a loose plastic container with creative graphics: black-and-white cute, cartoonish baby faces nestled into a fun, green-and-orange font. “Our designer, along with myself and my business partner, just sat down and came up with what we wanted the package to look and feel like,” Julie told me. “The three of us collectively designed it. It took us about a month.”

The Boogie Wipes team attended trade shows in these early months to get hands-on feedback about their samples, as well as to build product awareness. Julie told me, “We did a lot of trade show sampling to get feedback. But it wasn’t like we were out researching, ‘Should we do this?’ We were researching as we did it.” Once they were happy with the quality of the wipes, and before they had their packaging finished, they put sample wipes into generic white packets with a Boogie Wipes logo stuck to it and took them to the shows. In addition to handing out these samples at trade shows, they elicited feedback in two other key ways, while also building brand awareness: by leaving samples in doctors’ offices and kids’ clothing boutiques. And they didn’t limit this sample testing to their own backyard. “We geo-targeted pediatricians’ offices all over the country so that they could have them in their office and spread the word. Obviously, that’s our front line: moms who have sick children. We did it for feedback. We did it for exposure.”

Once they had nailed the product formula, they moved forward efficiently in applying for patents for both the formula for making the wipes and for their packaging. Since they were on a low budget, Julie worked very hard on much of the product patent application herself, even though she had no experience in the work, though she did get advice from an experienced lawyer. As I advised earlier about getting trademarks, hiring a lawyer to do this work might be a good way to go, but a number of founders I’ve interviewed have done much of the legwork for the lawyers themselves. Even Graham Snyder, whose device is so complex, wrote his patent applications himself—saving himself money when the attorney completed the legal work.

With their intellectual property protections in place, Julie and Mindee’s next order of business was figuring out how to manufacture the wipes, which as Julie says was the “tricky part.” This is generally true for novel manufactured products for two key reasons. One is that most manufacturers don’t want to take on small-quantity orders, and entrepreneurs usually want to start small, as they almost always should. Also, often it’s hard to find a manufacturer with the right equipment and experience to produce what you need.

For these reasons, most founders have to pay for first stock at a per-item premium above what an established firm would pay. So Julie and Mindee decided to go with a manufacturer in Israel. They ordered a twenty-foot container, which was a minimum condition, which amounted to 3,300 cases, or 39,000 units, costing roughly $20,000. That might seem like a big gamble, but they were quite confident in the market from the ongoing sampling they’d done.

Also, in discussing their decision to go ahead with this order, Julie stressed that they had carefully calculated that they could actually afford the order, and really knowing and understanding their financial situation was a key part of this decision. One thing to look out for during this step is that the process of getting your inventory often takes longer than expected, and if you have been banking on cash flow from sales earlier than you’re able to get the stock out to market and moving off shelves, you’ll quickly become cash-strapped.

I see so many new entrepreneurs struggle with cash flow and learn the hard way just what a big impact timing differences make on their working capital. Just consider how much cash gets eaten up to order and sell a typical physical product. You send $30,000 to a manufacturer; they take sixty days to produce your goods and ship them to you. Remember, you’re still incurring overhead expenses, which may include rent, payroll, and phone bills throughout this whole waiting period. Once you finally receive your finished product, you then have to pay to have it warehoused. You ship it to several retailers, who in turn take forty-five days to finally pay you for it. Some retailers also drag out payment even longer. So that’s 105 days without your $30,000 and nothing coming in. And, depending upon what agreement you reach with retailers, they may be able to return what doesn’t sell or is defective in some way, so you have to plan for that, as well. If you’re selling your product online, you should also plan for chargeback, which occurs when consumers don’t believe the product fits their standards and demand a refund from their credit card company.

Because this process of managing cash inflows and outflows involves so many unknowns, it’s important to create a detailed set of monthly cash flow projections before each quarter of the fiscal year. This, at least, allows you to do a good job of anticipating possible hits to your bottom line and to build in some cushion of cash to make up for any loss of income you might suffer. For example, if you are expecting a big reorder from a customer in March, you might want to keep enough cash in reserve for your March expenses to cover the expected income just in case the order doesn’t come in until April. You can create your own spreadsheet or utilize an easy-to-use preprogrammed tool like Intuit’s QuickBooks to manage this task. Each month you should begin with a cash balance, and below that, list sources of cash inflows and add them to the balance, and then list sources of cash outflows and subtract them, leaving you with your new cash balance. Update the numbers with budget versus actual each month. This will allow you to prioritize expenses well in advance and anticipate if you’ll likely need funding so that you can begin the process of chasing those funds.

You should also avoid waiting until right before launch to establish what your retail channels will be, and don’t put your hopes in only one basket. Julie and Mindee smartly moved on several fronts at once when pursuing retail placement. They pitched to boutiques and to grocers, exploring both the specialty and mass markets. They struck gold when they approached the buyer at the Fred Meyer chain, which is a division of Kroger in the Northwest, who put in an order for placement in about 120 stores in the baby section.

It’s vital to approach a range of retailers and experiment with sales channels. Hoping to be picked up by a major retailer like Walmart, Target, or Whole Foods and pitching to their buyers is just fine and a smart thing to do, but planning on them ordering from you isn’t. Most often, you need to have sales traction within independent stores or small chains before a large retail chain will take a chance with your product. You need to be able to show them how you’re already selling hundreds if not more of your product every day. You should probably also be aiming for sales through e-commerce sites and may also want to approach TV sellers, such as QVC and Home Shopping Network, if your product is right for those channels. Another route to retailers is to build relationships with distributors, who can act as a bridge to the retailers they work with.

One of the keys for Julie and Mindee’s success was doing a good job of deciding which critical functions should be outsourced versus which ones to do themselves, while also keeping closely engaged in the work they outsourced. They knew they had to go to a specialist in chemistry to figure out the way to combine tissue paper with saline, yet they were very hands-on with him in developing the right formula. They also knew that the design of the packaging would be critical to success, so they outsourced that as well and again worked very closely with the designer. For their marketing and publicity efforts, they had the expertise and skills for this, so they did all the blogging and outreach themselves.

In order to do a good job with this balancing act, I advise that you follow these three rules:

1. If you are good at a particular task and enjoy doing it, you should strongly consider taking charge of it yourself.

2. If a task is absolutely critical to success and you aren’t certain you can do it flawlessly yourself, then you should bring in experts to do it.

3. For simple tasks that are mostly administrative in nature but that can require a great deal of time and energy, you should outsource if you can afford to do so.

Beware of Estimates of Time and Cost, Even from Experts

No matter what kind of product you’re making or how detailed your plan—even if it’s fairly far into your development—and no matter how well you manage the process, expect that your costs will escalate and the time it takes you to be ready to launch will stretch out. This is as true for Web-only software products as it is for manufactured ones and brick-and-mortar services.

Hockey Stick Principle #30: Your time and cost estimates will always be wrong—always.

A great case demonstrating this is Doug Lebda’s experience in building LendingTree. His experience also speaks to the wisdom of getting started with building prototypes and market testing them right away. Recall that he wrote a strong and successful business plan that won second place in a competition at the University of Virginia. He received the advice of a consultancy with experience in the business of building Web site services for making his projections, and his plan called for building the application and marketing it on the Internet for two years, by which time positive cash flow was predicted. Doug’s original expectation was that building the Web site and writing the software to support the business would be fairly straightforward, and the plan was to pay two computer programmers fifteen to twenty dollars each per hour and to hire a Webmaster, who would be paid $40,000. But instead, Doug hired a consultancy that projected it would take only sixteen weeks, and cost much less, about $30,000. As Doug says now about the advice he got from the consultancy, “That team just didn’t have a clue.” What they delivered wasn’t close to what Doug needed to satisfy the banks or to process customer applications.

Fortunately not long after, Doug was able to raise $1 million from a group of angel investors headed by banker Jim Tozer, and he spent $300,000 of that to hire a high-quality programmer, Rick Stiegler, and hundreds of thousands more to hire a technology staff to work under Rick’s direction who spent several months building a workable application.

Graham Snyder ran into the same problem with predicting the true costs of building a functioning version of his antidrowning device. Recall, he’d already paid an engineering firm $20,000 but didn’t get close to having a finished product. These are stories you hear again and again when you talk to entrepreneurs about their product development process. My advice about this stark reality is to not get down on yourself if you miss your cost and time estimates, even if by a great deal. Even when building Vertical IQ’s product, which was my second go-around for a similar business, the process required twice the investment we had originally expected.

Agile versus Waterfall

You may not be developing a software product, so this section may not be relevant for you. But if you are, the following is important for thinking through the approach you want your development team to take.

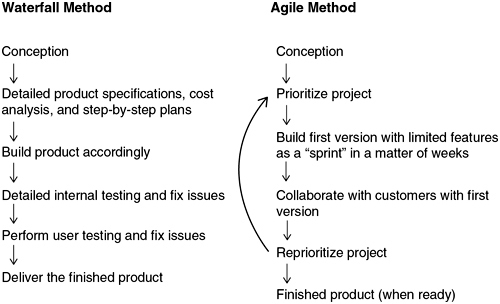

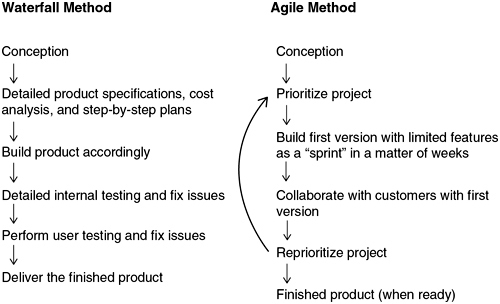

Doug Lebda’s experience with a faulty estimate of the amount of time it would take to program the site, and the innumerable headaches his programming team had to deal with over the course of three years, is a perfect example of the problems that have plagued software development and is what inspired the innovation of the agile development process to replace the established waterfall approach. Agile has steadily gained ground in Web product development, and Eric Ries incorporated the agile method into his Lean Startup approach. The agile and waterfall approaches are easily summarized by these schematics:

Which method is best? The right answer depends on your product type, personality, and budget. Generally speaking, the more established and predictable a product you’re building, the better a fit it is for the waterfall method. More innovative projects are usually better suited for the agile method because it’s so much more fluid and allows you to make plenty of mistakes along the way and correct for them as you go. Another positive of the agile method is that you bring the customer into the development process more, and they are both more engaged and better informed about what you’re building.

Once again, you’re not a corporation, and you are free to make your own choice in this regard. If you prefer to work in a more tightly planned and structured way, you might be best off with the waterfall method, and if you’re more comfortable with a more fast-moving, exploratory, and flexible way of working, waterfall will probably drive you mad. The truth is that many developers blend the two, which is often most realistic. A good way to do that is through embracing plans, details, and processes up front, but not spending so much time and energy on trying to perfect them. Then building a good prototype and quickly getting input from customers, much earlier in the process than you would according to the classic waterfall approach.

How Do You Know When You’re Ready to Launch?

The traditional approach to a product launch was to get the product all ready, get stock in stores, and then send out press materials to drum up as much coverage in as big a push as possible. Today, a big launch could mean pushing out videos introducing founders and product, social media announcements, user events, free product giveaways, and an e-mail campaign encouraging people to buy and spread the word.

Sometimes you’ve got to plan a “hard launch” because you’ve lined up an advertising campaign, scheduled a calendar of multiple events, for which you’ve had to book venues, or you’re tying your product into a specific date, such as Valentine’s Day. Also, if you’ve pushed a significant volume of product out to retail stores in advance, this is the kind of push you want, because you’ve got to get inventory to turn around as fast as possible to keep those commitments from the retailers and usually to also pay for that stock.

Hockey Stick Principle #31: A big launch may not be best.

But the process for many products has become much more complex and much less clearly delineated by a line in the sand of pre- and postlaunch. Beta launches have become commonplace with Web products, relying on early adopters becoming engaged with your product and helping to tweak it with their feedback. With development of e-commerce and the innovation of Point of Sale (POS) sales systems, such as Square, a more gradual, measured, “soft launch” approach is becoming popular even for tangible goods. That might involve starting out with Web promotion and sales through your Web site and on e-commerce sites only, or perhaps setting up some “pop-up” retail locations, renting space within a retail venue or an empty rental space in prime territories for reaching your target customers. Another approach is mobile boutiques, such as fashion trucks, that bring their product right to the neighborhoods where their target consumers live. This innovative approach to selling can become part of your brand and integral to your marketing.

A soft launch might also mean limiting retail to a select number of independent stores. This approach allows you to gauge market response and learn more about your market while also containing your initial inventory and cash flow needs.

Making a huge push right at launch may catch you by surprise with market demand and the intensity of follow through you’ll have thrust yourself into. A great example of this was the launch of Warby Parker’s lower-cost, elegantly designed eyeglass frames. They had truly identified a market gap. Stylish eyeglass frames were running in the $400 to $500 range, and Warby Parker offered appealing alternatives for just $95.

As one of the founders, Neil Blumenthal, recounted of the launch, “We knew we only had one shot. We launched on February 15, 2010, and it was mayhem.” Their PR operation had been hugely successful and articles had run in both Vogue and GQ. They sold out the inventory they ordered of their top fifteen styles, which they had anticipated to last their first year, within four weeks and had to tell twenty thousand customers that it would be three months before they could fulfill their orders. They handled the crisis well with high-quality customer relationship management, and the company went on to become a huge success. Still, it’s a cautionary tale regarding the intensity of an all-out, hard launch push.

Hockey Stick Principle #32: No matter how big your splash, sales may not come.

Even if you do make that big push, you may have the opposite problem, the market response equivalent of one hand clapping. You’ve fired on all cylinders and yet have generated virtually no coverage and little to no sales. Now what? You’ve experienced one of the great truths of entrepreneurship: Early adopter customers can be very hard to find. Maybe you’ve misjudged your market, maybe you’ve promoted to it ineffectively, maybe your pricing is off, maybe you just need more time to find your market, or you need to find a whole different market from the one you were targeting. Whether you launch hard or soft, chances are that you’re going to have to do a good deal of market development. The good news is that there are so many powerful tools and methods to keep trying, and we’ll dive into those in the next chapter.