Go, Go, Go!: Ramping Up Your Newly Discovered Model

The definition of the growth-inflection stage is that your revenue begins to surge because you have found repeatable actions that reliably result in sales. This is, of course, never really an exact point in time as it appears on a hockey stick graph; it’s usually a matter of many months of strong uptick.

When you have honed your model and you hit the growth-inflection point, the excitement you feel from the burst of positive customer response is like the state of play that sports psychologists call being in the zone. Your formation is in sync, and you’re finally making a good percentage of goals in relation to shots taken.

Or, to depart from the hockey metaphor for a bit, you feel like you at last have liftoff. The revenue growth you experience is like the phase of a rocket’s launch after it’s shucked its boosters and is bursting straight up to orbit. When iContact hit growth inflection in 2005, its revenue spiked to $1.3 million from $296,000 in 2004. For LendingTree, the spike was from $476,000 in 1998 to $8.0 million in 1999. Facebook’s spike was from $394,000 in 2004 to $9.0 million in 2005. For Google, it was from $294,000 in 1999 to $21.5 million in 2000.

A start-up in this stage has the new power of momentum, and this period of sales takeoff can be outright exhilarating. Good things start happening without you and your team having to work so hard for them. Prospects start calling due to word of mouth; you close sales much faster and with less hardball pitching; product enhancements are easier to plan and execute because you’ve got so much more customer feedback and more cash to put into them; employees are easier to recruit because they are more confident in your future; potential partners are starting to return phone calls. It’s like you’ve built up kinetic energy, the energy an object has because it’s in motion. Once you have this liftoff, you really feel the power.

Ryan Allis of iContact beautifully described how empowering this stage of growth is: “You need all the same processes to get to fifty thousand in monthly revenue that you needed to get to ten thousand. But when you’re at zero, you have nothing; when you’re at ten thousand, you got a heck of a lot that you can take advantage of to get to fifty thousand.” I can’t resist also quoting one of my entrepreneurial heroes, Ben Franklin, on this point who wrote this about his printing and newspaper business: “My business was now continually augmenting, and my circumstances growing daily easier, my newspaper having become very profitable.… I experienced, too, the truth of the observation, ‘that after getting the first hundred pound, it is more easy to get the second.’”77

Hockey Stick Principle #51: Don’t spend lots of money to fuel fast growth until you’re pouring it into a high-performance engine.

This is a critical time in which to apply the wisdom of the physics of motion. When the speed of an object is accelerating, it’s comparatively easy to further accelerate it, and that’s just what you want to do. This is the only way in which you want to significantly scale up your operations—on the basis of a model that has proven it works and when it’s clear to you why it works. Otherwise, you are pouring more and more fuel into a machine that can’t sustain liftoff.

The Pitfall of Premature Scaling

Knowing when and how to scale is one of the trickiest issues for founders to manage, and much research has shown that scaling up too early is, if not the single-biggest mistake founders make, certainly one of the top few. The Startup Genome Project study of 3,200 high-growth start-ups in the technology sector, which was conducted by a group of researchers from the University of California–Berkeley and Stanford University, including Steven Blank, determined that “74% of high growth internet startups fail due to premature scaling,” making it the number-one reason for failure. One of the most intriguing findings in the report they issued about the scaling problem is that “startups that scale properly grow about 20 times faster than startups that scale prematurely.” What’s so remarkable about this is that so many founders scale up too early precisely because they’re trying to spur faster growth.

So what exactly is premature scaling? And how do you know if you’re doing it? The Startup Genome group defines it as start-ups “focusing on one dimension in their operation and advancing it out of sync with the rest of their operation.” More specifically, the report identified three key mistakes: Founders decide to put too much money too early into growing “their team, their customer acquisition strategies,” or they “over build the product.”78 The only thing I’d add to that is that sometimes they do two or all three of these things at the same time.

The classic horror story of premature scaling is that of Webvan, which aimed to be the FreshDirect of its day. It opened for business in the San Francisco Bay area in 1999, quickly raised almost $400 million in capital, and went into high gear with a plan to expand to twenty-six cities, most notoriously signing a $1 billion contract to build a number of highly sophisticated warehouses, all before it had worked out many kinks in its operations. The company declared bankruptcy in 2001.

A more recent case is that of Monitor110, which was a New York City–based start-up that provided deeply researched information for investment bankers. The idea for the company was a good one, and it raised $16 million in two financing rounds. But the start-up quickly ran out of money and closed down in 2008. One of its investors and board members, Roger Ehrenberg, wrote in a postmortem about what went wrong:

Too much money is like too much time; work expands to fill the time allotted, and ways to spend money multiply when abundant financial resources are available. By being simply too good at raising money, it enabled us to perpetuate poor organizational structure and suboptimal strategic decisions.… We weren’t forced early on to be scrappy and revenue focused. We wanted to build something that was so good from the get-go that the market would simply eat it up. Problem was, with all that money we hid from the market while we were building, almost ensuring that we would come up with something that the market wouldn’t accept.

While in the blade years, following Paul Graham’s sage advice that sometimes it’s necessary in the early building period to do things that don’t scale is a great best practice. However, it is crucial not to misunderstand this as a justification for scaling up a model that doesn’t have true momentum. Doing things that don’t scale is all about giving you more time to keep crafting a good working model that will scale up well, which you must achieve before you begin pushing for scale, such as by pouring more money into marketing or expanding your operations by hiring more staff. Scaling up in those ways before you’ve fixed your model is not a way to fix your business; it’s a temporary crutch, and before long, it won’t keep your business propped up.

This doesn’t mean that you don’t sometimes have to make investments well ahead of getting the returns from them. For example, when I hired my first salesperson at First Research, I had to start paying his salary well in advance of getting the revenue I hoped and expected he would bring in, which was one of the hardest decisions I made, because at that time, in the spring of 2000, I was still making very little revenue. But during the course of 1999 and early 2000, I had spent a great deal of time experimenting with selling subscriptions by various methods and to various markets, and I was beginning to reliably land sales with a combination of banks, CPA firms, and consultants. I had refined my selling process. I had learned to run successful free trials, figured out the best way to find warm leads, who the right people to call were, and how to convert a good percentage to customers. I had figured out my repeatable actions and honed a good machine. That’s why I decided it was time to make the move, and I brought in Wil Brawley, the ace salesman who was later hired by Schedulefly to grow their market.

Wil needed some time to build up the pipeline, which is important to account for as you scale your sales operation—growing sales generally requires a significant lag time. By mid-2000, my sales were picking up as I had expected, and we earned $227,000 in revenue that year. For the first time, I paid myself some salary, though just $11,200, and I paid off the roughly $30,000 I’d borrowed to get started. I didn’t then hire a big force of salespeople and try to move into overdrive. I hired one more salesperson, plundering Bank of America where I had worked from 1993 to 1999 to bring over Lee Demby, a sales guy I knew was good and would make a good fit for us from my days working in sales at the bank. I also personally kept selling, and selling with Wil and Lee in 2001 was for me the best of times for First Research.

As Wil recalls fondly, “Each prospective customer was like a new game of chess. Some of them left the king, the decision-maker, exposed relatively quickly. But most made you work hard to get to that king. I knew we’d win every single game if we stuck with it long enough. People saw it in our eyes and heard it in our voices. We sold a great new product with fire, passion, energy, enthusiasm, confidence, love, and honesty. We were genuine. Our product was unique.” I knew that we now had a scalable model for just these reasons; we knew where we were aiming, and we were scoring much more often. We were working hard to make sales, yes, but they were coming in reliably. In 2001, we earned $726,000 in revenue, and I paid myself a salary of $74,700, and in 2002 we nearly doubled our revenue, broke the $1.5 million barrier, and were in growth inflection.

But I continued to scale up incrementally. I brought in more salespeople in carefully measured steps that coordinated with our increases in sales, and I made sure that they all understood and could execute on what I came to call the “Wil and Lee method.” That was the linchpin of our success; we drilled into the Wil and Lee sales method by training people in it well and steadily adding more of them.

Hockey Stick Principle #52: Scale up only in step with the success you are already generating; don’t try to force the machine.

Big Bangs Can Lead to Big Busts

The growth-inflection stage may seem “all good,” but the challenging decisions you have to make about ramping up in this period can all too readily lead you to crash and burn.

One big pitfall is that the surge in growth you’re seeing may be a fluke. Strong upticks in sales can be another kind of false-positive. The lift turns out to be a one-off occurrence, or it may be premised on market and sales pitches that are too good to be true and therefore are not repeatable.

A striking example of this is the meteoric growth and spectacular crash of Amp’d Mobile. For a time, mobile virtual network operators—which offered cell phone service plus content, such as streaming videos—seemed like the big new thing in mobile, and in 2006, Amp’d was hot. It targeted a particularly desirable niche, the high-use eighteen- to thirty-five-year-old market, and attracted $360 million in investor funding, including backing from MTV. That year, Amp’d had 100,000 customers, and with all of that newfound investment money, they poured fuel on their fire, running a series of ads on MTV starting that November and continuing for several months. The effort seemed a fantastic success; they soon had 175,000 customers. That sure looked like classic hockey stick growth. The problem was that huge numbers of those new customers never paid their bills. By June of 2007, the company filed for Chapter 10 bankruptcy and reportedly had just $9,000 left in its coffers.79

Until you’ve seen strong growth for at least several months and you can identify whether or not the fix or fixes you’ve made to your model are working well and exactly why they have helped you grow, it’s premature to conclude you’ve truly taken off.

The popular mantra to “go big fast” can lead founders into all sorts of traps in this stage. One of the great ironies of start-ups reaching the inflection point is that faster growth can have revenge effects, meaning that it can lead you to believe certain new investments are required in order to sustain it or to take it to a whole new level, and those outlays can come back to bite you, sometimes badly.

Veering from the Game Plan

In chapter 5, we discussed how pivoting and tweaking are important elements of success during the blade years. It’s true that the blade years are a time of trial and error and open-mindedness. But as a start-up is beginning to experience success and hitting its growth-inflection point, a common mistake made is that rather than drilling even more into what’s working, founders instead make a change or set of changes that actually violate their model. At this juncture, you should still go with what’s working well and build upon that. Of course, that doesn’t mean you should never pivot or tweak after the growth-inflection point, but do so without sacrificing what’s working well for your business.

Hockey Stick Principle #53: Once you’ve achieved takeoff, focus on accelerating with what’s working; now is the time to scale up, not to keep making changes.

In the case of Amp’d, the founders decided to relax strict credit requirements for new customers, the result being that rather than drilling deeper into their successful customer base, they extended into the high-risk sector, which was a violation of their model. In hindsight, this seems an obviously crazy thing to have done. But in the heat of the takeoff moment, founders make such ill-conceived decisions all the time. Sometimes, they make many of them.

Go back to the case of Fab.com. Recall that the founders decided that in order to continue growing, they needed to begin building up inventory of items for sale so that they could offer faster delivery. To do that, they determined that they should build their own warehouse, one of the highest ticket expenses for a company to take on. They also assigned themselves one of the hardest of all business feats to pull off when they took on the burden of estimating in advance what customer demand would be for items. But there was more. They decided to expand into Europe, which proved a fiercely competitive market. Perhaps most problematic, though, was that they veered off the path of offering truly distinctive, beautifully designed items, broadening their offerings so wide, that, as an Inc. article highlighted, “the company had strayed so far from its commitment to design that it had begun selling steaks.”

To his credit, cofounder Jason Goldberg wrote a blog post about a number of lessons he learned from these mistakes, and he sums up well by saying, “We had started to dream in billions when we should have been focused on making one day simply better than the one before it.”80

Operating at a Loss Is Overrated

One of the biggest factors for founders to consider when they are deciding which is the best course to take after they’ve reached takeoff is whether or not the surge in earnings is accompanied by a surge in profits. Sometimes you’ve crafted a model that begins to pump out more and more profits for only a marginal increase in expenses. But just as sometimes in order to get your sales to take off you’ve got to invest in efforts that aren’t profitable in the shorter term, sometimes once you’ve hit sales takeoff, you face a similar challenge. In order to sustain growth, further investment in no- or low-profit growth may be required.

Hockey Stick Principle #54: Losing money on sales is not a growth strategy.

If you do need to operate at low or no profitability for a time, you must have a strategic plan for growing out of that situation and into good profitability by a predictable time. If you can’t see the way forward to making good profits, it’s imperative that you seriously dive back into examining your model and come up with an answer for how you’ll do so.

The notion that it’s okay for start-ups to spend more on growth than they’re earning has gained popularity due to some famous cases of companies that have taken a low- or no-profit approach to growing, such as Amazon. The company has poured its revenues back into investments aimed at gaining additional market share and launching new products and services to further fuel growth, and in order to fund these investments in growth, it has not shown profits on its annual statements. But Amazon can sustain its lack of profit because it’s earning an enormous amount of revenue and demonstrating year after year that its revenue is growing. The notion that a start-up shouldn’t even expect to be making profits for many years is dangerous. Amazon is an exception; very few start-ups make anywhere near the revenue it generates, and the path of their future revenue is much less predictable.

Just what level of profitability you should be aiming for is a tricky issue. The fact is that certain kinds of business models simply have higher profit margins than others, for various reasons. For some, competition is negligible, which gives them pricing power, the extreme case of which is a monopoly. For others, once the up-front costs of designing and producing the product are paid, each sale is made at very low cost, as is the case with many software products. Every copy of a new version of Microsoft Office sold costs the company a negligible amount to produce, so the company achieves a very high volume of sales with effectively no additional expense required. That is essentially why Microsoft has maintained profit margins ranging from 20 to 30 percent or more for years. Another high-margin business was razor blade maker Gillette that had 60 percent gross margins before being acquired by Proctor & Gamble.81 The Apple iPhone has practically printed money for the company since the day it was launched. Businesses with such strong profitability can achieve phenomenally fast growth.

Examples of low-profit-margin businesses are construction and certain types of retail, such as grocery stores, which have little pricing flexibility because of such intense competition. Many of these businesses are perfectly viable, even highly lucrative, and they can be managed well because the reasons why they are low margin are clear. The same is often not true for start-ups. A low margin of profit can be more difficult to justify and can leave you vulnerable to market changes. So if you haven’t reached good profitability even though you’re seeing surging sales, you’ve got to carefully scrutinize where your costs are going, what benefits you’re seeing from them, and what the trajectory of your profitability will be if you continue growing in this manner.

One example of a low-margin business that has a compelling rationale for how it will grow its way out of a lack of profit is marketing software firm Marketo that was started in 2006. In 2014, the publicly traded firm had revenue of $150 million, a 56 percent increase above 2013, but it lost $54.3 million in the process.82 This has been a trend for Marketo for years. Its SaaS business model is one that’s often profitable, but Marketo is deploying the adage that you have to spend money to make money. In a February 2015 investor presentation, its executives showed how from 2011 to 2014, its net income from operations has improved from negative 65 percent to negative 19 percent, respectively.83 Gross margins are also improving. In addition, while in 2011, Marketo was spending 32 percent of revenue on R&D, that had dropped to 17 percent in 2014, and the company projects it will drop to 15 percent or lower in the future. As Marketo highlighted, its target profit margin is a healthy 20 percent, so in that regard, the company is on the right track.

The point here is that Marketo appears to have a clear plan for becoming profitable. While the plan does involve risk, the company has established that it can reliably increase revenues and improve margins. If you can’t similarly anticipate attaining better profitability in the future and identify exactly what you’ll be able to, you’ve got to take your low profitability very seriously. You don’t want to become a victim of “We lose money on each sale, but we’ll make it up in volume.” That almost never works.

It’s also important to be intensely aware of economic conditions and any trends that may affect your business. This is always true, of course, but for money-losing models, it’s particularly important. If the economy turns downward and sales drop, while at the same time investors aren’t investing, you’re in a very precarious situation. Keep in mind that US recessions tend to occur every seven to ten years, and even though this has been so well established, they always seem to arrive when you least expect them. If you’re profitable, but at a low rate, you may well be able to sustain strong enough growth to get you through such a squeeze by rigorously watching your expenses. But plan ahead and make sure your business is ready by maintaining relationships with key investors and keeping cash on hand to get you through a rough patch.

Invest in Profitability or Growth?

What if profits are in fact beginning to pour in? Many pundits argue that you should continue to invest all, or most, of your new cash into growth in this stage rather than banking it as profit, if you’re indeed a growth business. That same argument is used to advocate for raising a big infusion of venture capital at this stage so even more money can be pumped into growth. However, operating with razor-thin margins and raising outside growth capital are sometimes fraught endeavors, with so many ins and outs to delve into that the next chapter is dedicated to it entirely. For now, let’s stick with just the scenario of reinvesting most or all your profits.

Lots of founders go this route, pursuing market share generally either by jacking up sales and marketing efforts or investing in launching a wider range of products. This is a key reason why operating losses are common for several years for start-ups rather than their model just not being profitable. Facebook lost money until 2009, but by 2014, it earned $2.9 billion, so this strategy worked just fine for it. And its profits are the envy of all other social Web companies.

Hockey Stick Principle #55: If you invest all or most of your profits in growth, the growth must be worth more than the profits.

There are many good strategic reasons for investing most or all your profits in further accelerating growth. One is that you are seeking to solidify first-mover advantage, meaning that you’re the first company to the market with a product of your type, which can give start-ups a lead that competitors may never catch up to. But solidifying that lead may require investing in building brand recognition and customer loyalty. According to Boston University’s Professor Fernando Suarez and Professor Gianvito Lanzolla of Cass Business School, the three reasons first movers have an advantage are: (1) gaining a technological edge, (2) being first to obtain scarce assets, such as location or patents, and (3) gaining an early base of customers.84 You can be outflanked on each of these all too quickly by competitors if you’re not investing in continuing to improve your technology, expanding into good locations and obtaining new intellectual property IP, and aggressively leveraging your customer base to reach new markets.

On the flip side, if you’re up against a competitor with first-mover advantage, the best strategy for growth may be to invest more heavily in initiatives to take market share away from that leader. All founders should always keep in mind the possibility of being outflanked by competitors and also the opportunities they might have to be the one doing the outflanking. You might realize that your key competitor has a vulnerability, and it might make great strategic sense to invest in building up your own operations or improving your product or service in order to capitalize on that vulnerability. Maybe the market leader has offered a streaming service, but it’s plagued by glitches. You might invest in offering your own streaming service with better technology. It’s important to always be making proactive strategic moves vis-à-vis competitors and looking for good opportunities to either solidify your advantage over them or get a leg up on them. Perhaps your customer research has indicated strong demand for additional services or a wider selection of products. Investing in that kind of improvement to fuel growth is great business. You’ve also got to be willing sometimes to invest in improvements if you want to remain competitive. In a different category, your growth may have reached a point that substantial additional investments are required to sustain it, such as additional warehousing or server capacity.

But even when your rationale is strong for forgoing profits, you want to be able to see the profitability at the end of the tunnel. While for superfast-growth businesses with potentially enormous markets, going five to ten years before reaching breakeven and starting to bank profits or pay dividends is often just fine; for more niche businesses with smaller markets, I recommend no more than three or four years. And if you do opt to forgo banking profits, it’s vital to continually scrutinize the course you’re on very closely, asking really tough questions of yourself like:

• Is the growth I’m generating worth the cost because it is setting me up for even stronger growth to fend off the competition? Will I clearly generate larger profits in the future?

• Do I really have to worry so much about competition? Is the market large enough for several leaders? Or is my market segment specific enough and deep enough that I can rely more on word of mouth and the quality of my product, customer relationship management, and marketing rather than on pouring more and more cash into marketing and advertising?

• Is there a critical window of time in which I’ve got to capitalize on the market opportunity, or can I opt to grow more steadily and slowly?

• Are there any ways that I can introduce greater efficiencies in our operation or optimize economies of scale in order to produce at least some profit as we expand?

In making these evaluations, you should systematically weigh all the pluses against the minuses. In other words, do the best cost-benefit analysis you can. In doing so, an important factor to consider is how you are compensating your staff. If you’ve got fast growth and yet your employees aren’t sharing in that wealth, you can undermine their morale and their trust that you value their contributions.

Hockey Stick Principle #56: Your employees should not be asked to forgo banking profits; reward them commensurate to your rate of growth.

Let’s face it: In the early growth stages of a start-up in particular, the work hours and the responsibilities heaped on staff can be daunting. Using some of your profits to show them you’ve appreciated their hard work and sacrifice is a great way to boost motivation and strengthen the company culture. Some founders go way overboard, offering lavish bonuses and paying exorbitant salaries, but others make the mistake of being perceived as Scrooges. I’ll offer advice about how to get compensation right coming up in chapter 8, which covers building your team.

Fixed or Variable, Most Costs Are Significant Commitments

We’ve all read stories of start-ups hiring too many people and moving into expensive new office space, quickly bankrupting themselves. The dot-com bust in 2000 and 2001 was replete with ghoulish examples, such as the appropriately named Boo.com. The founder of the online clothing retailer, Ernst Malmsten, once notoriously said, “After the pampered luxury of a Learjet 35, Concorde was a bit cramped.”85 These cautionary tales have raised awareness of the danger of scaling up too fast. However, with the availability of so many inexpensive business support systems, there’s now a lot of help for you to contain costs from scaling. But even so, keeping control of your finances is a challenging feat.

One of the common ways in which founders get their start-ups into a profitability bind is by investing too heavily and too soon in fixed costs. An important distinction in operating expenses is between fixed costs, which are those you have to commit to in advance and that you won’t be able to increase or decrease readily—if at all—and variable costs, which rise and fall with your sales volume. For example, your costs of manufacturing enough smartwatches to fill demand will vary by volume, while your costs to warehouse your stock of them will be basically fixed—you pay for warehouse space by the space you rent or build, not by the space you fill.

Hockey Stick Principle #57: Achieving fast growth is not a license to spend.

Scrutinizing your fixed costs especially rigorously is vital in plotting all stages of growth, but it can be a very tricky issue at this juncture because, with such fast growth, the tendency is to err on the side of spending too much too soon to sustain that growth. That’s one of the biggest pitfalls for fast-growth start-ups. For all these costs, it’s best to seriously consider if there are any other options, or even to test those options, before committing to the expense.

A better choice for the Fab.com cofounders in entering the business of inventory management, for example, might have been to contract for warehousing services until the change in the business model proved successful. While over the long haul building your own warehouse may be more cost effective than leasing space or contracting for warehouse services, you should carefully consider whether the additional cost of leasing for a year or two would be worthwhile because leasing would give you time to evaluate whether or not you really needed the space and wanted to potentially build your own space. Of course, very few start-ups face this particular decision at this stage of growth, but even working out the amount of warehouse space to lease—or for SaaS models, the server capacity and cloud services you choose—is a calculation that has to be made with great care.

Even with retail space, you may have alternatives that let you test the benefits before locking into leases that turn out not to be profitable, which is another of the very common revenge effects of fast growth. Say you’re thinking that you need to expand from online-only sales into some brick-and-mortar retail locations. Perhaps you should try some “pop-up” stores first to test response and verify best locations for your business.

Fixed costs are hardly the only tricky part of getting expenses right. Variable costs and discretionary costs, such as your marketing and sales expenses, can also be extremely challenging to make good decisions about. For example, with variable costs, there’s often a time lag that can bite you. The classic case is overordering of inventory and then facing a drop-off in sales. As for sales and marketing costs, many start-ups fall into the trap of pouring a great deal of money into higher-ticket campaigns that don’t produce a commensurate increase in sales. In fact, the Startup Genome study of start-up failure found that this is one of the key differentiators between those who scale up well and those who falter. The study found that start-ups that failed due to premature scaling were more than twice as likely to “spend more than one standard deviation above the average on customer acquisition”—meaning that most of those firms were spending a great deal more than the average firm.86

Be a Smooth Scaler

The core issue here is whether you have a model with scalability. This is so vital to the success of start-ups that Steven Blank, a professor, author, and entrepreneur, makes scalability part of his definition of what a start-up is: “A startup is a temporary organization designed to search for a repeatable and scalable business model.”87

But what exactly is the definition of scalable? Many explanations are deceptively simple, such as that offered by Investopedia: “A scalable company is one that can maintain or improve profit margins while sales volume increases.”88 Or consider this explanation from the cleverly named Divestopedia: “Scalability … refers to a company’s ability to add significant revenue and not be constrained by its own structure and resources.”89 One puts the emphasis on profit margins, the other on revenue, and one emphasizes sales growth while the other stresses organizational issues and costs. All these issues combine in determining scalability.

I think there are two key ways to evaluate whether you’ve achieved scalability. One is when you’re able to grow your revenues without having to increase costs as quickly. The other is when you can grow your revenues without making major modifications to your business operations. My favorite expert quote about this is from scalability expert at Siemens Corporation André B. Bondi, who says that scalability is “the ability of a system to perform gracefully as the offered traffic increases.”90

Hockey Stick Principle #58: Scale up operations only as fast as your team can skate and still stay in well-coordinated formation.

Whereas in the prelaunch to early postlaunch phase, you’re scrambling as fast as you can to move forward on all fronts and you often can’t help but operate in a state of controlled chaos, when you’ve reached growth takeoff, you want to be vigorously focusing on fine-tuning your operations. My advice is that rather than making any substantive changes to your model during this growth-takeoff stage, you work hard on continuing to maximize the performance of your model.

In Doug Lebda’s office on his whiteboard, he showed me a calculation that revealed the profitable machine behind LendingTree’s strong sustained growth. He knew the math of his model cold, with an exquisitely tuned understanding of the relationship between how much money it costs LendingTree to obtain a marketing lead (e.g., $50 per new lead), its lead conversion rate (e.g., 10 percent of those leads became a customer), and how much revenue it would get from each closed sale (e.g., $500 per closed sale). His key advice about honing for scalability is this: “Keep driving down your marketing cost to get a customer; keep driving up your revenue per lead.”

During the growth-inflection point, founders should have a firm understanding of the mathematical reasons their business’s growth machine is working or not. At its most basic level, having a successful business ultimately requires earning a healthy profit on sales. That’s why on the TV show Shark Tank, the sharks always ask the founders, “How much does it cost you to make your widget, and how much do you sell it for?”

The founders of iContact also paid extremely close attention to honing a scalable model in this phase. Ryan Allis explained the beauty of this process this way: “The appeal is that the return from the cost-per-click model is predictable and scalable. By gathering data over several years, iContact was able to show that, for every dollar they put into marketing, they got back a customer who would spend a certain amount of money with them over a number of years.” So iContact knew exactly how much to spend on additional advertising in order to generate a precisely calculated amount of new business. Because sales growth was so predictable, the company was able to confidently scale up rapidly. In the next chapter, we’ll see how iContact used this predictable model to raise funding that resulted in surging growth.

Calibrating the Machine with Metrics

The right way to manage a start-up in the growth-inflection stage—and really from here on out as you grow—is, metaphorically speaking, like calibrating a machine: the process of configuring a machine to ensure it’s working properly. To calibrate something, a calibration specialist (that’s a real job) conforms or adapts a noncalibrated machine with a standard machine, meaning one that has been known or proven to be accurate. The process of calibration is important because if a machine isn’t calibrated, the parts it produces will drift toward lower and lower quality. Food will be packaged with the incorrect mix of ingredients, or tools will be forged at the incorrect length or weight.

Founders must be like calibration specialists. And you can’t calibrate well if you’re not keeping close tabs on your metrics and making sure you’re measuring the right variables.

Some of the most obvious measurements to keep your eye on are monthly revenue, revenue run rate (annual revenue divided by twelve), gross margin, and operating margin. After the obvious ones, there are hundreds of key performance indicators (KPIs) to choose from depending upon what type of business you’re managing. For example, if you’re an online SaaS firm, some of your important marketing and sales KPIs might be the number of new leads generated per month, the number of prospect demos provided per month, Web site traffic, renewals and churn rates (or the percentage of customers that discontinue their service), and prospect to customer conversion rates. Some KPIs are quite specialized by type of business. If selling products online, for example, a key KPI should be how many prospective customers fail to actually purchase after having put items in their carts.

Not all founders are data people, and that is fine; you don’t have to be. But you absolutely need someone who is. I recommend you hire a top-quality, experienced manager who has a deep knowledge of how to identify and track results for KPIs. This person doesn’t have to be a CPA or accountant, but he or she should have demonstrated experience with this process. And creativity is important; this is not just a matter of following preestablished rules. You need someone not only to track what’s happening but to help with the tricky costs and benefits calculations involved in making decisions about future growth. This requires not only a quantitative assessment but a qualitative one, as well.

Hockey Stick Principle #59: Do not let numbers make decisions for you; the qualitative must be paired with the quantitative to make good choices about growth.

Say that you’ve hit $1,350,000 in annual revenue, and for simplicity’s sake, that your income statement looks like this:

Revenue: |

$1,350,000 |

|

Product Maintenance Costs: |

($200,000) |

|

Cofounder Salaries (2 founders): |

($200,000) |

|

Marketing and Sales Expenses: |

($397,000) |

|

(Salaries, Commissions, Web Marketing, etc.) |

|

|

Customer Service: |

($50,000) |

|

Travel, Office Supplies: |

($20,000) |

|

Health Insurance: |

($40,000) |

|

Rent: |

($50,000) |

|

Operating Profit: |

$393,000 |

|

Suddenly, you’ve got a good pool of profit to work with and are in a nice position to make some investments in accelerating last year’s growth. How should you allocate the funds? Some payoffs from expenses are much more quantitatively obvious than others. One example from above could be the affiliate marketing program into which you paid $40,000 to get referrals for sales. Let’s say you earned $250,000 in revenue from the affiliates. That’s a very clear return and a pretty good result. So you’ll want to increase your number of affiliates.

Figuring out which of your marketing programs are leading to sales can be trickier because marketing requires a great deal of time and measurement in order to see if it’s working or not. That’s why using such tools as customer relationship management (CRM) systems and lead tracking is important from early on, which large providers like Salesforce.com and Microsoft Dynamics offer. They are also provided by some less expensive start-ups, such as Zoho and Insightly. These tools give vital information for making this difficult assessment. But even with these diagnostics, you often can’t know the return on investment (ROI) of various efforts, such as new product enhancements, product upgrades, packaging tweaks, and hiring new salespersons, until months or years after you’ve spent the money. This is one reason why qualitative judgment is also so critical—you have to make your best evaluation based upon what you’re hearing and learning in the marketplace in order to know what marketing methods to invest in.

Take the case above again. You’ve learned that increasing your number of affiliates will produce good results. But doing so will take a fair amount of your time because you have to build a partnership with each affiliate, including convincing them on the idea and—if you’re successful—entering into an agreement. You might determine that hiring an additional rep for direct sales is a higher priority than investing more money into your affiliate marketing program. Maybe you’ve noted that in the last few months the ratio of deals to calls has ticked up, and the size of deals closed has also been improving, so you’re convinced that more person-to-person selling will produce increasing returns. Also, you’ve still been working on sales yourself, as I was in First Research’s takeoff year, and hiring another rep will free you up to focus more on strategic planning and implementation.

For me with First Research, in 2001, having invested more in the sales operation allowed me to refocus my time, largely on two key tasks: analyzing the customer feedback we were getting in order to prioritize product improvements and targeting some new, potentially lucrative markets. Both worked well for us. We added more frequent industry updates, industry news features, additional financial data, e-mail alerts, and training, and we developed a system for investing new customer payments into product features. I was also able to land a number of important new accounts with large outsourcing firms, such as ADP, and software firms, including Microsoft, as well as their network of value-added resellers, and dozens of others. Our revenue increased from $797,000 in 2001 to $1.8 million in 2002, in large part due to the combination of my new efforts and the sales brought in by the new rep.

Developing good metrics and keeping close track of them is only the baseline of start-up management; metrics don’t make the most important decisions for you. In fact, an interesting finding from the Startup Genome report is that “Google Analytics, homegrown solutions and spreadsheets are the top 3 three tools that are used by more than 90% of all startups to track their metrics and make decisions.… There are slight differences between consistent and inconsistent companies but we didn’t interpret it as significant.” Note that the report refers to start-ups that are scaling prematurely or dysfunctionally as “inconsistent” and those that are scaling up smartly as “consistent.” The important point here is that the type of data analysis being used was not a key factor in whether start-ups were scaling correctly or not. This underscores that it’s the quality of the decisions you make in light of the data that makes the difference, and these decisions must be made according to judgment calls based on your intuition, your assessments of the talents of your team members, and your deep understanding of your customer base and why and how you can grow it.

As only a very general guide to prioritizing outlays, I advise that in this growth-inflection stage, you allocate profits in this order of priority:

• keeping at least five to ten months of cash in reserve to cover overhead expenses should need be (I often say to my partner in Vertical IQ, Bill Walker, “We need to store up nuts for winter!”)

• employee raises and bonuses

• new sales and marketing expenses

• new expenses associated with maintaining and improving your product or services

• founder salary increases

• debt repayments

From Early Adopters to Early Majority

One of the great challenges of sustaining growth in this phase is that it generally involves what marketing specialist Geoffrey Moore called “crossing the chasm,” in his classic book of that title, meaning moving from a customer base of early adopters into the larger pool of what he calls early majority and late majority customers. The fact that this can be so difficult to do is the main reason that spending too much on customer acquisition is such a common error. With some cash in their coffers, many founders decide to make a big marketing push involving an expensive advertising and PR plan. Sometimes doing so can work very well, but there is one big caution. Before you make such an investment, you must be sure you really understand the needs and desires of the majority. Ideally, you want to build a bridge to the majority by leveraging the knowledge you’ve gained from your early adopters and by making as many of them as you can into brand evangelists.

Hockey Stick Principle #60: Nothing can bring in more new fans better than your early fans.

A great case of a founder who discerned how his early adopters were the key to bridging to the wider customer base is Bob Young. For Red Hat, the early adopters were computer programmers who mostly called the 800 number or ordered on its Web site. The majority adopters the company wanted to reach were corporate technology directors who could decide to make larger orders for departments or whole corporations. But when Bob first pitched them, they were having none of it. They would respond with one or another version of “You’ve told me that there are only fifty of you working away in the tobacco fields of North Carolina and by your own admission are writing maybe 5 percent of the code that I would buy on your disk. And the other 95 percent of that code you have only a good guess where it’s from, but you really don’t know. Just how long do you think my career would last in front of either that bank inspector or my board of directors?”

But Bob knew that many server administrators, often from the same company and many levels below the technology director, would approach Red Hat’s trade show booth and buy a copy. Those customers were buying Red Hat to satisfy a specific yet unbudgeted need. For example, an HR manager at a firm needed to send internal announcements, so she would ask for help in doing so. If she didn’t have $10,000 in her budget to buy the necessary software, the server administrator would suggest an inexpensive workaround—paying $49.95 to install Red Hat. These first corporate purchasers had heard good things about Red Hat from the early enthusiasts who were avid participants in the user community Red Hat had worked to create through its Web site. The decision to compete on price combined with this quality service to early adopters created a bridge into corporate purchasing. Over time, the company had sold so many copies to firms that the technology directors would realize that Red Hat was in fact an inexpensive, flexible, workable solution and that they needed to account for hundreds of Red Hat applications already running on their servers. They’d need to prove they had a license to use it, and they also needed support to keep Red Hat up-to-date for them. So more and more technology directors started calling Red Hat asking to purchase site licenses and make deals for ongoing support rather than Bob having to do a hard sell on them.

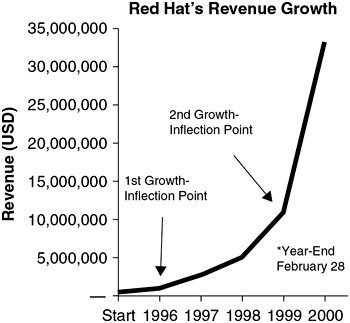

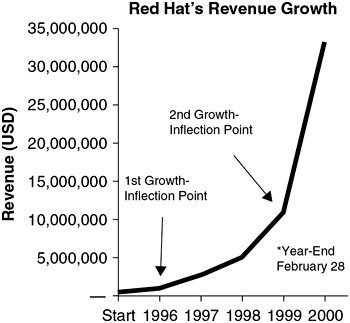

This is why Red Hat’s growth curve has two points of distinct uptick. Its growth-inflection point occurred only a year after it got started, after Bob had worked out the innovative sales model, and then three years later, growth really took off when large-scale corporate sales kicked in.

Build a Community, Not Just a Customer Base

Red Hat mobilized its early adopters so well in large part because it stayed closely engaged with its users and created a vibrant platform for their needs. The Web site became a hub for Linux discussion groups in addition to downloads of the program and applications. And this was way back in 1999, before even social media had been born, let alone Facebook brand pages morphing into platforms for offering ongoing “brand experiences,” as Red Bull, Coca-Cola, and others have become such masters of. At the time of writing this book, Red Bull has forty-three million likes on Facebook and two million followers on Twitter, and its Web site is chock-full of entertaining, extreme sport videos. Red Had was a pioneer of community creation. In March 1999, RedHat.com had 2.5 million page views.

INSEAD Professor Jean-Claude Larréché highlights in his book The Momentum Effect that the “‘customer’ is much wider than simply the product purchaser,” and Bob Young understood that important truth about customer relationship building.91 Red Hat customers really did become part of a community. Bob understood the culture of the community and its ethics and aspirations, and he communicated that in all his marketing to them. In speeches and interviews, he compared proprietary software companies like Microsoft to “feudal lords,” which was exactly how so many in the IT community felt. He was skilled at connecting emotionally with both customers and potential buyers, and that played a vital role in turning more of those community members into purchasers.

Hockey Stick Principle #61: Customers don’t just want a product; they want a relationship.

One of the key differentiating features of founders who successfully rally their early adopters, creating brand evangelists and establishing a strong and appealing brand identity that acts as a magnet to draw in more and more and more customers, is that they convey an authenticity of connection and communication with customers. They don’t rely only on traditional techniques like listing benefits in their marketing. They understand the point that Harvard marketing professor Youngme Moon articulated well in her book Different: Escaping the Competitive Herd:

Marketing is the only function within the organization that is expressly designed to sit at the intersection where business meets people. Real people.92

Rather than launching a high-ticket marketing campaign to stoke growth at this stage, founders should focus on connecting in real ways with those real people and being creative about ways to do so, many of which are relatively inexpensive.

Grasshopper, a firm whose product lets you run your business using cell phones, mailed twenty-five thousand chocolate-covered grasshoppers to five thousand influential bloggers, reporters, politicians, CEOs, entrepreneurs, and TV anchors and then posted the media attention they received (which was lots) on its Web site. This idea was a huge success. Ben Silbermann, founder of Pinterest, wrote seven thousand notes to users himself asking them about why they joined the site and what they liked about it.93 That was clearly a considerable investment of time, but it was a low-cash, high-quality way to connect and also to learn. He credits the process with helping him to tailor Pinterest to users’ desires.

Let Customers Know the True You

Though you will almost surely want to hire a professional firm to collaborate with you on your marketing, you should not simply outsource this function. Your marketing should be an authentic expression of your brand identity, and in this stage of growth—and ideally for many, many more years to come—your brand identity should be an authentic reflection of you and your mission. As talented as many professional marketers are—and they can truly be brilliant—they can’t give you that, and if you don’t develop your own deep understanding of your brand identity and what appeals to your customers, you might be led astray by the pros.

Hockey Stick Principle #62: Catchy taglines and clever ads are no match for an authentic brand identity.

Joe Colopy, founder of six-time Inc. 5000 fastest-growing firms, Bronto Software, a cloud-based e-mail marketing provider, is a great example of a founder who has fashioned a strong brand identity and knows exactly how important it is to growing the company. He has built his firm’s marketing around a playful green brontosaurus logo. When I visited with Joe at the Bronto headquarters, bright-green brontosaurus blow-up toys and stuffed animals were everywhere. He told me, “The brontosaurus humanizes our technology. It’s approachable. We’re regular, folksy people; we’re open, transparent, and tell it like it is. We make business fun. And no one hides behind a title here. These are the core things as to who we are.”

He went on to tell me, “Marketing agencies don’t quite get why we have a green dinosaur representing our identity and want to do things with it or change it. They consider it is something that can just be used and changed for campaigns and that’s all it is. But it’s not all it is. It’s way more than that. I won’t cheapen it, ever.”

Bronto’s green brontosaurus is a perfect case of what marketing specialist Seth Godin advocated for in his influential book Purple Cow—it is marketing that is “worth talking about, remarkable, new, and interesting.”94 Companies at their growth-inflection point are in a great position to follow this approach and stand out by having a lot of personality.

There is so much focus on social media marketing and content marketing being new ways of engaging customers and building community, and they are extremely powerful tools. But just as with the data from measuring metrics, they don’t do the work for you. It’s the quality of your marketing much more than the fact that you’re broadcasting national ads or videos on the latest hot mobile platform that builds a community. And by building a strong brand identity and nurturing your customer community, if and when you do decide to launch a major marketing campaign, you will be much better equipped to make sure it speaks in your company’s voice.

Doug Lebda of LendingTree did a great job of this when he decided to launch a prime-time cable television and radio campaign during the company’s growth-inflection stage. He and his marketing team chose to work with a small, creative, and entrepreneurial advertising agency, Mullen, located “in the woods” near the north shore of Boston. They worked closely together to craft a tagline and approach to the ads that brilliantly expressed empathy with the frustration of trying to get a mortgage loan, the very frustration that was Doug’s motivation for starting the company. The tagline, “When banks compete, you win,” clearly conveyed the customer focus, and the ads struck right at the heart of the customers’ pain point with irreverent humor. The first television commercial, titled “Rejection,” featured a casually dressed couple in their middle-class kitchen interviewing bankers in three-piece suits. The couple speaks to two bankers at their kitchen table: “Your rates are a little high. What’s the word I’m thinking of?… No!” And the couple laughs gleefully.

Doug attributes much of LendingTree’s success at scaling to the effectiveness of the campaign.

Partnering and Licensing to Expand Your Reach

Another important approach to scaling up your customer base in this stage is to pursue licensing deals and partnerships with large brands. These deals can provide a start-up with massive leverage for revenue growth because the reach of these brands to customers is on such a large scale. And at this stage of growth, you are a much more attractive partnering prospect than you were before takeoff, so making deals will be a much more efficient process.

Many of the founders profiled in the Hockey Stick study had great success with scaling up through such deals. Red Hat negotiated a whirlwind of product integration, co-marketing, and distribution partnership deals with such global software and technology companies as IBM, Dell, Intel, Compaq, Oracle, SAP, Netscape, Hewlett-Packard, and Novell. When Bob called on them, it turned out that their customers were already asking for a Linux solution, and by that time, the big firms wanted to figure out a way to capitalize on the potential, or at least not miss out on its value to their customers.

Another firm that benefited from deals like this is Shashi Upadhyay’s start-up Lattice Engines. It has struck partnership deals with Oracle, Salesforce.com, Microsoft, SAP, and DemandGen, just to name a few.

The types of deals you should look into are:

• Product integration paid partnerships that license your product, patent, or technology to other firms in exchange for a set license fee. Oftentimes, start-ups may license only parts of their intellectual property. For example, a start-up may embed its product into another company’s core product to make a more compelling offer.

• Free product integration partnerships wherein you license a portion of your product for free to other firms to enhance their offering, and in exchange, you receive brand awareness and marketing prospect leads. The goal is to enable your brand and product to reach a broader audience and attract interested buyers who become sales leads.

• Revenue-sharing sales and marketing partnerships with companies that promote your product within their existing channels. There are many ways to do this, such as media deals, affiliate marketing arrangements (discussed in chapter 4), and resale arrangements.

Hockey Stick Principle #63: Big firms don’t have all the power; they want your innovation and hustle as much as you want their market muscle and customers.

I’ve heard founders say that they worry that big companies will push them around if they partner with them. Well, they might if you’re not tough, but that’s up to you to stand your ground. Keep in mind that if they’re interested in a deal, they may need you as much as you need them. Sometimes these partnerships do lead to merger discussions because they enable larger firms to learn firsthand how well a start-up’s product fits into their larger offering—such as how it sells and for how much. This outcome could be a good thing or a bad thing, depending upon your goals. Moreover, it’s important to keep in mind that whatever revenue the larger company is producing for you, their portion of the revenue may be discounted when the valuation of your company is being calculated by the investment community, should you decide to pursue venture funding. That’s not necessarily a problem, just an important thing to be aware of and account for yourself.

One thing that is a real risk to be cognizant of is that if a large company becomes your largest revenue producer, it may have more leverage over you in future negotiations than you’ll be happy with. In order to mitigate this concern, I encourage founders to diversify their revenue as much as possible in most cases. You don’t want to be in effect owned by any one other company.

When it comes to making these deals, the devil is in the details, so my advice is to lawyer up. There are dozens of considerations to be aware of. Are you providing them pricing control? Who will handle customer support—you or your partner? How much control does your partner have over your trademarks, if any? What is the deal’s duration or term? One year or five years?

The term is a really important provision to pay close attention to. If you wind up not liking the deal, and if the term is for many years, you’re stuck with it. I’ve seen long-term partnership deals severely hurt the profitability of a start-up. Negotiating these agreements is no time to try to save on legal bills by using an inexperienced attorney.

Whatever methods you use to scale up successfully, as your momentum builds and the power of your model is confirmed, you’ll be in a good position to raise growth capital, if you choose. Firms may now even be calling on you. Getting an infusion of growth capital can be the boost that pushes you solidly onto a long-term growth trajectory. But there are many cautions, so in the next chapter, we’ll closely investigate the pros and cons.