Playing in the Big Leagues: Raising Growth Capital

Though scaling up by investing only your earnings into growth is a good way to calibrate the process of gaining hockey stick growth and helps assure that you don’t get way out ahead of your revenue generation, there are also many good reasons to decide to seek substantial outside investment. As I said in the last chapter, sometimes raising substantial capital is the key to allowing you to grow fast enough to secure a dominant market position, especially when you must outflank a competitor who’s either coming on strong or threatening to take market share from you—or whose market share you are gunning for. A good example is the market battle between next-generation taxi services Uber and Lyft, which offer essentially the same product with the same business model. In order to secure their future, each has no real choice but to expand rapidly, and each has raised many millions of funds from outside investors in order to do so.

Even if you aren’t facing competition that threatens your market share or your future survival, you may want to gun for the fastest growth possible, the best reason for doing so being that you’ve confirmed that your model can reliably scale up much faster and capture a much larger market. A great example of founders who made a good call on this is that of Ryan Allis and Aaron Houghton of iContact. Though they had bootstrapped so successfully to reach growth inflection, their in-depth analysis of the market and the speed with which their sales took off—hitting $1.3 million in revenue in 2005, just three years after launch—assured them that they had a huge additional market to grow into.95 Roughly thirty million small businesses operate in the United States, but only a few hundred thousand had adopted e-mail marketing tools at that time. At that point, they could likely have sold the company for $3–$5 million, if not more, but instead, they opted to raise outside funding and shoot for even more accelerated growth.

They started by raising $500,000 from nonprofit accelerator NC IDEA. Then between 2007 and 2010, they went on to raise $53 million in six different rounds, continuing to pour that money into their scalable model.96 Raising funds in measured increments based on their well-honed ability to generate revenue was the key to their smooth road to success even while growing so fast.

As Ryan explains, “The whole business is based upon a mathematical model where we invest $500 to acquire a customer and can get $2,500–$2,600 in lifetime revenue. So it takes about eleven, twelve months to pay back that up-front investment. And then that turns into three years of gross profit after that.” The precision, reliability, and profitability of their sales model convinced funders to continue offering infusions of cash. By 2010, sustained fast growth provided a strong case for a much larger infusion, and they hired Allen & Company, a New York City–based investment bank with a rich history of helping successful online businesses, such as Google, raise capital to help secure a larger deal. In August 2010, JMI Equity, a Baltimore-based growth equity firm, invested $40 million in the company. In 2012, publicly traded marketing firm Vocus acquired iContact for $169 million.

You may also need to raise funds in order to make the major capital investments required to sustain growth—things like equipment, space, or systems, which simply can’t be covered by current earnings. For example, when Julie Pickens and Mindee Doney of Boogie Wipes secured a very large order from the Fred Meyer grocery chain for placement in about 120 stores, they hadn’t been in business long enough to have banked enough revenue to cover the costs of fulfilling that order. They needed to get a good dose of cash to pay for inventory and for shipping to the retailers, who wouldn’t be paying for many months. They successfully raised a strong cash infusion that carried them through this critical growth juncture.

Hockey Stick Principle #64: Raise capital to boost or sustain strong growth, not to search for it.

The most fundamental mistake founders make when seeking substantial outside funding is trying to do too much too soon—before they can make a strong case for the firm’s growth potential or, even better, have a proven record of that growth. They waste a great deal of time and experience enormous frustration—and often disillusionment—because funders just aren’t buying their pitch. Once you’ve got fast growth that you can clearly demonstrate is based on a solid and scalable model, attaining significant outside funding is much more viable. Investment firms may even come calling on you and compete to do business with you. That was true for Dude Solutions, for example, which completed its first fund-raising round in 2014, obtaining $100 million from private equity firm Warburg Pincus.

Founder Kent Hudson waited fifteen years from launch to seek this infusion, preferring to be in a strong growth position. “We didn’t run a [fund-raising] process with twenty private equity firms,” he recalls. “We said this will be a ‘by invitation only’ party.” He didn’t even write a five-year business plan, which is generally a baseline requirement when approaching funders. He recounts, “We told them, ‘Here’s our market analysis. Here’s the market potential as we see it and the opportunities. Here’s the competition. Who would like to team with us to exploit the position we’re in? Now let’s jointly talk about how best to exploit it.’”

Capital Is a Form of Control

One of the primary cautions about seeking funding is that it generally involves some loss of control over the company to the outside investors. Waiting until you’re in a strong growth position before raising money can give you the negotiating leverage to maintain more control.

Hockey Stick Principle #65: Venture capital always comes with strings attached; make sure they don’t bind you.

While most angel investors offering seed money act primarily as advisors and don’t seek a controlling share of your firm, the venture capital and private equity investors who offer more substantial investments require a good deal of control over the future course of the company, including seats on the board. If performance isn’t meeting the standards they have set, you are in danger of them hijacking the company and taking it in a different strategic direction or of being forced out of your leadership role. Much too often, founders find themselves in a mighty struggle, or even outright war, with their backers.

One founder who went through such a battle wrote a thoughtful and cringe-inducing account of the ordeal, which is a great cautionary tale for all founders to consider. Philip Greenspun and partners started ArsDigita, a provider of open-source software for online learning communities, with just a $10,000 investment. The company had made many good deals with major firms, including AOL, Hewlett-Packard, Levi Strauss, Oracle, and Siemens. By 2000, the firm was making $20 million in annual revenue, with good profitability, and it had become a strong prospect for venture funding. The partners decided to go for it. Greenspun recounts that they made a combined deal with a venture capital firm and private equity group for $38 million in funding in exchange for a 30 percent stake in the firm and, as Greenspun describes, “veto power over certain kinds of big transactions, such as the buying of expensive capital equipment, the selling of the company, the acquiring of another company.” The terms also included a stockholders agreement, which Greenspun discloses required him and cofounder and fellow shareholder Jin Choi to elect a board of directors that would include one representative of the venture firm, one of the private equity group, three senior officers from ArsDigita—including the CEO—and two outside directors.

This arrangement gave the funders two seats out of seven. But shortly thereafter, the founders decided to bring in an outside CEO, and they chose a person who had been recommended by one of the funders. This person came on board before they had brought in the two outside directors. Suddenly, the weight of authority on the board had shifted to the funders and the new CEO, who controlled three out of five sitting directors. As plans for rapid growth were pursued, the company expanded, and Greenspun recalled in a case study on waxy.org that the new board more than doubled the number of employees from eighty to two hundred. Furthermore, they paid those employees much more than Greenspun had, increasing salaries to more than $200,000 for executives and programmers base salaries of $125,000. He reports that he began to disagree about the course in which the company was headed, but because candidates he put forward for the two open board seats were not approved, he could not regain decision-making authority.97

You can avoid such a painful scenario by understanding the three basic means by which founders lose control: 1) allowing someone else to own more than 50 percent of the voting stock; 2) losing majority control of the board of directors; 3) entering into contracts that override voting control on how certain functions are governed. For example, if you own 51 percent of the shares, you can normally elect the board of directors, but not if you contractually agree to give certain shareholders the right to elect a majority of the directors. That’s one way that VCs gain more control.

This can happen to even business-savvy founders. Doug Lebda was a highly professional business manager, and yet he ran into trouble with his board and feared he might be ousted after he had made a significant deal for additional funding. That deal was premised on a financial forecast, but LendingTree missed those numbers by a significant amount. He had predicted that sales would grow considerably in the fourth quarter of 1998, from the third-quarter revenue of $100,000, but the fourth-quarter number was only $116,000. The funder had obtained a seat on the board as part of the deal, and he said in no uncertain terms that the performance wasn’t acceptable.

As is true with virtually all business projections, LendingTree had run into unforeseeable setbacks. One was that the banks weren’t converting leads to closed mortgages at the rate predicted, which was a problem that, as we discussed earlier, took Doug time and intensive work to solve. Another problem was that spending more on advertising didn’t equate to the higher proportion of leads that had been forecasted. When the company spent $1,500, they got three hundred leads, but when they spent $150,000 they didn’t get thirty thousand leads, not even close. Meanwhile, the cost of buying keywords from Yahoo! and other search engines had increased significantly. And finally, a Web site relaunch was delayed. These are all problems that are entirely typical for founders to run into but also entirely unpredictable.

Because he had offered seats on the board for not only the most recent investment but earlier ones, as well, Doug had lost voting control, and now suddenly he was at risk of losing the company. The board didn’t immediately make a decision about whether to keep Doug on as CEO or fire him; they decided to put him “on watch.” He smartly decided to pursue a transparent, team-focused atmosphere with the board by scheduling weekly meetings to update them.

Hockey Stick Principle #66: Managing your relationships with the board is as vital as managing your relationship with customers.

“After the January board meeting when I thought I was going to be fired, I quickly went from being scared to being completely determined to prove myself,” he recalls. “I wanted to be totally transparent with the board. I wanted them to believe in the business the way I did. I didn’t want to hide anything or be defensive. Also, I needed their advice and buy-in.” By solving the problem of how banks could get higher conversion rates, later in 1999, LendingTree was turning its business around and had made deals to work with an impressive number of heavy-hitting banks, including Bank One, Bank of America Consumer Finance, Citibank, First USA, and JPMorgan Chase & Co.

Doug also didn’t let the experience deter him from raising the additional capital needed to continue the new surging growth. On September 20, 1999, LendingTree closed a $50 million financing round by selling convertible preferred stock to a group of investors, including Capital Z, GE Capital, Goldman Sachs, Marsh and McLennan Risk Capital, and Priceline.com. “We went out targeting twenty million and ended up raising fifty,” Doug says. “As long as we can raise money, we said, ‘Let’s keep trying to go big.’ If we had failed to raise the capital, we would have retrenched.”

The lesson isn’t that pursuing outside capital is too risky; it’s that it is inherently risky and that you must be highly cognizant of the predictions you’re making and the strings attached to them. If you do decide to seek substantial outside funding, you must be extremely vigilant about the terms you agree to and highly strategic about your approach.

Why You and VCs May Not See Eye to Eye

It’s important to understand the fundamental goal you are committing to in taking VC funding and to understand how VC firms themselves are funded in order to appreciate why tensions sometimes develop between founders and VCs.

VC firms manage pools of investment dollars that they raise from large institutional investors—predominantly insurance companies, university endowments, and banks—as well as high-net-worth individuals. These investors are made limited partners of the firm, or LPs, while the partners inside the venture firms are called general partners, or GPs, and they make the investment decisions and run the firm. The investment money from LPs is pooled into funds of, say, $100 million, which are used to invest in a portfolio of start-ups—say, ten or fifteen—and a VC firm will generally be managing a number of these funds. GPs typically also invest some of their own money in a fund and have a stake in its returns, and they also draw a salary. A fund may have $50 million or up to $1 billion, with the typical fund having about $150 million.

Over a three- to five-year period, the VC firm will invest a fund in outlays generally ranging from about $1 million to $15 million per start-up, with the typical investment traditionally being about $3 million to $5 million. The minimum investment is normally $500,000, but occasionally, VCs may invest as little as $100,000 in a seed round, as discussed earlier. The series of VC investments made into a single firm are referred to as “rounds.” The first round is the “seed round,” followed by the Series A Round, Series B Round, Series C Round, and on. These rounds are typically eighteen to twenty-four months apart, and the amount of investment tends to grow larger and larger. The median amount raised in the A Round by the forty firms that I studied in the Hockey Stick Research Study that raised venture money was $5 million. Big ideas that experience really explosive growth may obtain rounds faster. Uber’s A Round was $11 million in February 2011; its B Round was $37 million in December of that same year; its C Round was $258 million in August 2013. By April 2015, it has raised $4.9 billion total through several more rounds.98

Venture firms typically invest in later-stage start-ups that can be underwritten based on well-founded revenue projections. In 2014, of the $48 billion invested by VC funds, only 1 percent, or $718 million, in 192 deals was invested in seed stage deals. The balance was invested into early stage—also called growth stage—at 33 percent, when the business is less than three years old; expansion stage (41 percent), when the business is experiencing rapid revenue growth and in business more than three years; and later stage (25 percent), when the company is growing revenues and its product is widely available and may have positive cash flow. The later stage may also include a mezzanine financing round, or a loan that can be converted to ownership if not repaid, also called bridge financing because it’s invested with the express understanding that it is being used to help get the company to a public offering or an acquisition.

These investments in start-ups are not for perpetuity; the express intent is to assist them in achieving fast growth for the purpose of “exiting” from the investment at a strong profit, ideally either by the start-up going public or being sold in a merger or acquisition deal. The VC firm charges a fee for the amount invested, generally of 2 percent, plus a significant percentage of the funds raised either by the IPO or the sale. The VC is generally looking for all the start-ups invested in by a given fund to exit within five to ten years of the fund’s creation so that the fund can then be dissolved and the profits distributed between the GPs and LPs.

Hockey Stick Principle #67: Once you accept venture capital, you’re on a ticking clock to either acquisition or IPO.

The first rule of seeking venture funding is not to do so unless you want to either take your company public or sell it and unless you want to do so within the time frame of five to seven years—or usually at most ten years. The second rule is that if one or the other of these exit strategies is your goal, you examine very carefully—and with the guidance of experienced professional advisors—what will be required to make your company ready for a successful exit and what growing pains that will entail. You cannot rely on the VCs to make that assessment for you, no matter how experienced they are.

It’s vital to appreciate that while the venture firms’ GPs take considerable risk in making their investments, the fees they earn and the portfolio methodology of creating the funds insulates them from much of the risk of the individual investments. This in no way means they don’t make decisions carefully; they are extremely judicious and selective. They are also generally highly disciplined in focusing on a particular type of company and sector, such as biotech start-ups or start-ups that are on a clear path to IPO in the relative short term. A 2014 study “Specialization and Competition in the Venture Capital Industry” by professors from Northwestern, Duke University, and Rice University reveals that only 14.3 percent of VCs are generalists; most specialize in sectors such as medical (12.7 percent), or computer-related (19.4 percent).99

They are absolutely investing in a start-up with the strong incentive and the fiduciary commitment to help it achieve great success in exiting. But they are also doing so on a predetermined, though somewhat flexible, time line for achieving the best possible exit from the investment. This means that the pressure for the level of growth that will make the start-up appealing either to market investors or to possible acquirers can become extremely intense. And given the portfolio structure of funds and the comparative insulation from the risk of failure the VC firms are exposed to, it can also lead firms to choose to cut their losses if a start-up isn’t performing up to goals. In this event, because they’ve taken on so much debt from the firm, founders are forced to either sell on unfavorable, fire-sale terms or shut down and liquidate—that is, if they haven’t been forced out before this point.

Many, many start-ups have benefited enormously from both the infusion of cash they received from VCs and their guidance, like Google, Facebook, Uber, and iContact. The point is not to ward off all founders from pursuing it but to stress that it is higher risk than other kinds of outside capital they can target, even though no interest payments are involved, as with a bank loan, because of the time line imposed on hitting benchmarks for growth. The good news about how difficult it is to obtain VC and how risky it can be is that VCs certainly aren’t all-knowing entrepreneurship masters who you need to guide you to success, and there are many other good options for outside funding, such as super-angel investors or debt financing, which I’ll discuss later in the chapter.

The Wrong Reasons for Seeking VC Money

The fact that so many of the most successful start-ups in recent times have raised enormous sums of venture capital along the way to their ascent means that there is a popular myth about venture firms that exists today. For example, VCs make a higher return on investments than typical market vehicles, like stocks and bonds, and they steer start-ups away from dangers and give them the sage strategic advice that lifts them to runaway success.

Hockey Stick Principle #68: Venture capitalists do not lead start-ups to success; they bet on them being successful.

It’s true that many VCs have been successful entrepreneurs themselves or have learned a great deal about the process of growing a firm due to their experiences working with many successful ones. VCs also have lots of connections with people they know who can help your firm—such as access to key personnel, sales leads, future investors, and partnership opportunities. But the degree to which a start-up can expect to benefit from their experiences and connections may be exaggerated. For example, the average investment rate of returns for VC investing over the past ten years in 2013 was 7.8 percent, compared to the S&P 500 of 10.6 percent over the same period.100 That’s not good, considering the fact that venture capital attracts greater risk.

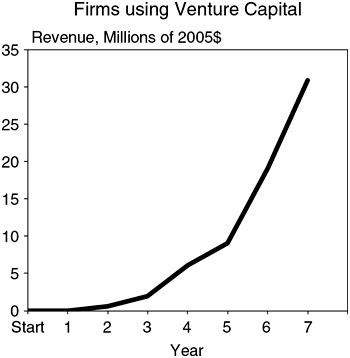

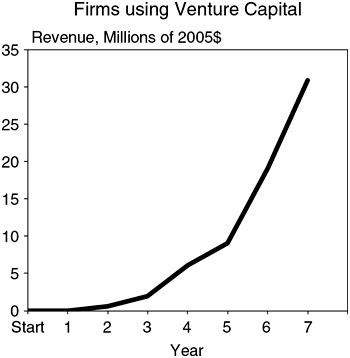

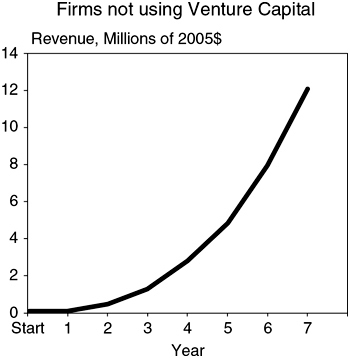

Yet VC-backed firms do grow much faster. My Hockey Stick study shows that firms that raised VC grew larger faster than those that did not raise VC. After the second year, for firms that didn’t accept VC investment, the median revenue was $358,000, while for those that did take VC money, median revenue was $463,000. By the seventh year, median revenue for those that raised VC was $29.6 million versus $11.6 million for those that didn’t. But whether this means that the VC cash and guidance helped accelerate growth or whether the VCs did a good job of choosing firms to back because they were well equipped for growth can’t be determined.

The graph below is the growth path for VC-backed firms and shows revenue increasing from $0 to $29.7 million in seven years.

The graph above is the growth path for non-VC-backed firms and shows revenue increasing from $0 to $11.6 million in seven years.

The Kauffman Foundation’s Diane Mulcahy, herself a former venture capitalist, made the case that venture capitalists have struggled to earn returns commensurate to the risk they take in an influential Harvard Business Review article:

The story of venture capital appears to be a compelling narrative of bold investments and excess returns.… The reality looks very different.… Numbers [show] that many more venture-backed start-ups fail than succeed. And VCs themselves aren’t much better at generating returns. For more than a decade the stock markets have outperformed most of them, and since 1999, VC funds on average have barely broken even.

She also highlights that while some VCs do give substantive guidance, others hardly get involved at all.

If you asked the CEOs of 100 VC-funded companies how helpful their VCs are, some would say they’re fabulous, some would say they’re active but not a huge help, and some would say they do little beyond writing checks.101

In fact, Shikhar Ghosh, a senior lecturer at Harvard Business School who has held top executive positions at eight technology-based start-ups and has conducted extensive research into how companies that have raised VC have performed, warns about the odds of success when going the VC route. While the National Venture Capital Association says that 30–40 percent of venture-backed start-ups fail, which is a high percentage, according to Ghosh, the failure rates are actually much higher than that. This isn’t better understood, he says, because the venture capitalists “bury their dead very quietly.”102 What’s more is that failure often follows fast on the heels of a VC round. CB Insights, a venture capital database company, conducted a survey of VC-backed failures and learned that on average firms fail or get “acqui-hired” (meaning a start-up is purchased for dirt cheap, but its founder is hired by the acquiring firm) only twenty months after receiving financing and raising on average $1.3 million.103 So the window for success is short-lived.

Venture Capital Is Not the Only Game in Town

So much of the coverage of funding for start-ups is focused on VC deals, but there are other less risky ways to go that will result in less intense pressure for faster growth. These other sources of capital have been gaining ground, and all founders should seriously consider them, especially in light of the fact that the odds of making a VC deal are, at any rate, quite slim. Entry into the VC club is still an exclusive affair. In 2014, $48.3 billion was invested in only 4,356 deals104 out of the three million firms working at the time on high-growth-potential start-ups in the United States.105 That computes roughly to one-tenth of 1 percent of founders having received venture capital! And 2014 was a big year for VC. In 2013, venture capital firms invested only $29.4 billion into just 3,995 deals.106 Also, some firms raise multiple rounds of VC, so the number of firms raising capital is less. In fact, according to one recent study, it was discovered that angel investors actually fund sixteen times more deals than VCs do.

You might think that the percentages are actually higher if you limit the firms included to fast-growth companies, eliminating the many lifestyle businesses and less innovative, slower-growth firms. But research by the Kauffman Foundation indicates this is not true. A survey of the 479 fastest-growing companies in the United States from the Inc. 500 / 5000 database in 2013 showed that only about 6.5 percent of them had raised venture capital.107

So while the media talks a lot about venture capital, in reality, very few firms actually raise it.

Hockey Stick Principle #69: Think of accepting outside capital as investing your equity; take a portfolio-management approach.

A great way to approach obtaining financing is to raise it from several sources at the same time, which allows you to distribute the stakes funders have in your company and is less dilutive of your control. Daniel Isenberg, professor of entrepreneurship at Babson College, and pharma executive Daniel Lawton describe the pluses of this approach.

When you scale up, it is faster, more feasible and less dilutive to cobble together your financing from a combination of equity investors, banks, public funds, suppliers, credit cards, customers, and even employees who will take stock options in lieu of some cash.… It doesn’t make as glamorous a story as “raising $5 million from top-tier Valley VCs,” but this is how growth financing typically works in reality.108

Lawton offers one example of creative funding opportunities. For instance, a retailer he knows “discovered that the $100 or so penalty to defer California sales tax by a month was actually a cheap source of financing.” The retailer discovered that paying the relatively inexpensive $100 penalty allowed it to keep large sums of cash on hard to pay for inventory, rent, and other expenses for the business. This only applies if you live California, but his point underscores the fact that you have to be creative and consider as many options as possible to improve your cash flow.

Another option is to approach so-called super-angel investors, who have been increasingly blurring the traditional line between venture funding and angel investing. Super angels may either be high-net-worth individuals who invest substantially more than the traditional angel investment of between $50,000 and $100,000 or formal groups of angel investors who do so, which are also sometimes referred to as micro VCs. One founder who went the high-net-individual route is Red Hat’s Bob Young. He was repeatedly rejected by venture capitalists during the company’s first four years. They just didn’t believe in Red Hat’s innovative model, telling Young, “Well, you can’t make money in the software business if you give your software away.” His explanation of why Red Hat could in fact do so and wasn’t likely to make good money any other way simply didn’t sway them. When he did eventually raise substantial capital, it was $2 million in funding from angel investor and businessman Frank Batten, Jr., who decided to take a chance on the unique model.

The super-angel investment groups are something of a hybrid between angel investors and VCs, and they bridge the gap for many start-ups between seed funding and the larger commitments of the VCs. These groups pool the investment money of a number of individual angels, and the investment decisions are made by the management, which differs from the groups described in chapter 2 in which angels make their own decisions individually about investments, though many of them may decide to join together in doing so.

A study by the Center for Venture Research at the University of New Hampshire showed that angel investors now fund sixty times more companies than VCs do, and much of that is from super-angel groups.109 They typically offer funding between $250,000 and $500,000 and attach fewer strings to the offer, generally not requiring, for example, a seat on the board. Such a force have they become that it’s been putting pressure on VC firms to begin making more investments earlier and in this range between seed funding and the traditional Series A offer.

Prominent super-angel groups include SV Angel, started by Ron Conway, a leading angel investor who has backed many of the most successful start-ups in the past couple of decades, such as Google and PayPal; Founders Fund, started by PayPal cofounder Peter Thiel, which has invested in Facebook, Mint.com, and Spotify; and 500 Startups, founded by Dave McClure, which has invested in Udemy and SlideShare among many other successes. You can get good information about many more of them easily through a Web search.

Another possibility to explore is finding a strategic corporate partner. These are larger companies, which may be private or public, that have created investing arms, such as Intel Capital; Steamboat Ventures, a part of Disney; Bloomberg; Microsoft; Qualcomm; Salesforce.com; and Samsung. Key advantages here are that the partner may become an appealing buyer and that these partners can provide access to much wider sales and distribution capabilities. But keep in mind that they are only going to be interested if your business makes a good strategic fit with their own, and they are sometimes criticized for trying to impose too much influence over developing in ways that align with their mission and may not be as appealing to founders.

A founder who raised funding from two different strategic partners, which was instrumental in getting to strong growth, is Doug Lebda of LendingTree. He had traversed the country pitching to top-grade investors and though conversations with a few notable firms advanced promisingly, nothing came of the efforts. He got all the way to the last step with SoftBank Capital, a Japanese VC that had invested in Yahoo!, but that deal also vaporized.

Then in the spring of 1998, Phoenix Insurance Group invested $3 million because it could leverage LendingTree’s technology to reach more customers. This is a great example of the kind of strategic fit firms will be looking for. The jolt of fresh capital allowed Doug to hire twenty more employees and significantly grow the company’s customer base. Later in 1998, LendingTree raised an additional $7.5 million more from pension fund Ullico, the Union Labor Life Insurance Company.

Another option that’s been gaining traction is revenue-based funding (RBF), which is being offered by a growing number of firms that specialize in these deals. The firms offer a fixed amount of money, as with a bank loan, but rather than charging interest on a fixed schedule, they take a percentage of the start-up’s revenue over the term of the deal, which is limited to a “cap” amount negotiated as part of the deal. Once the cap is reached, the deal is completed. Harvard professor and specialist on innovative start-up growth Clayton Christensen referred to this as “royalty capital” in a discussion of the benefits of these deals, in which he highlighted that they involve no award of equity, so are not dilutive. They also put no pressure on a founder to either go public or seek a sale.110 According to Thomas Thurston, the president of research group Growth Science, which analyzes reasons start-ups succeed or fail, the royalty percentage charged is generally 1–10 percent of monthly gross sales, and the cap on the amount to be paid is generally between two to five times the amount of capital awarded.

Thurston advises that this is only a good option, though, for start-ups with healthy gross margins, as with smaller margins, such cuts into revenue could quickly become problematic. He recommends, “This kind of funding only tends to work for startups with 50% or higher gross margins, or otherwise flexible margins so that the royalty doesn’t choke the business.”111

A Portfolio Approach Is Diversified but Highly Selective

While raising funds from a range of sources is advised, you should also be cautious about the risks of taking on too many financial investors from too many different backgrounds. This was one challenge Doug Lebda faced when he was in trouble with the board. He recalls he had a “motley crew of investors”—an insurance company, a pension fund, and a hodgepodge of super angels with different backgrounds. Addressing all their concerns took a good bit of his time.

Another case of conflicting investor demands is that of Trax Technologies, a fast-growth B2B firm that automates the process of finding and correcting errors in freight shipping invoices. Its founder and CEO, J. Scott Nelson, raised money from a few different VCs, and he recalls, “Interests weren’t always aligned.” He also cautions about the time spent on investor relations, pointing out that he “had to spend a lot of energy helping the investors understand the company. That took away from strategy and other opportunities.”

Hockey Stick Principle #70: Choose your investors as carefully as they are choosing you.

How VCs Will Value You

If you do decide to pursue VC funding, it’s important to understand the complicated set of factors they will use to calculate their valuation of your firm, which is a large determinant of the terms that they will offer. Valuations are an art rather than a science, but this is a good basic set of factors that will go into the equation:

• Revenue and earnings for comparable firms: How have closely related firms been performing?

• Growth rates of revenue and profit: Firms that are growing 300 percent are generally going to be perceived as higher future value than those managing only 10 percent, of course, but absolute size of revenue and profitability also factor in.

• Scalability and profitability of the business model: Does this business model make money? What are the potential gross margins and operating margins? How expensive is it to service customers? Are there big economies of scale to be had?

• Management experience and skill: This is a major consideration. In negotiating with VCs, it’s important to show them you are in command of your business and have the required expertise to run it and that you have a strong management team. Particular qualities VCs value in founders are that they are open-minded and surround themselves with experts, as well as that they have already successfully started a company or two.

• Intellectual property: How much intellectual property do you own? Do you have any patents, trademarks, copyrights, or other assets that are difficult for others reproduce? Try not to overvalue your IP, because most VCs recognize that IP can only take you so far. But in some circumstances, especially with patents, the quality of your IP can significantly boost your valuation.

• Size and hotness of the market: What’s the potential size of the market? How many potential customers exist in this market, and how much would they pay? How many of all the potential markets have you actually sold to? How much potential do as yet unexplored markets have?

• Propensity for being acquired: Is your firm the type that larger strategic buyers would be interested in acquiring? Can you name several large firms that would want to buy your company and have good reasons why it would make sense for them to do so? Have other firms in your market already been acquired?

• Competitors: Ironically, having lots of competitors in your market could be a good thing for VC negotiations, albeit that’s mostly true if you have a big market to sell to. Competitors validate the worthiness of your idea. iContact had at least dozens of competitors when it was raising VC.

• Competition from other VC firms: If you’re a hot commodity and have a great idea in a large market plus management skills, several firms may be bidding higher and higher to invest in your firm.

• Market conditions: Stock markets, the amount of money flowing into VC, the economy, and the condition of the market you sell to are all factors that impact how much a VC will value your firm.

• VCs financial modeling: VCs leverage elaborate financial models to estimate the returns they might earn on a deal. One well-known such formulation is the Venture Capital Method, created in 1987 by Harvard professor William Sahlman, which takes into account pre-money valuations (the value of the company just before an investment is made), post-money valuation (the value of the company just after the investment is made), and the terminal value (the value of the business when it is sold).

VCs run calculations based on these metrics and other models to figure out how much money they can return to their investors.

They’re Investing in You as Much as in Your Model

While attending a venture capital conference, one general partner speaking on a panel summarized the key selection criteria of VCs with memorable efficiency: “We look for talent, talent, talent.”

What does talent consist of, exactly? VCs are looking for many important management qualities. Experienced venture capitalist Ed McCarthy with River Cities Capital Funds, a Cincinnati-based VC with $500 million under management, says that some of the most-prized qualities are having a great start-up leader who is a team player and isn’t defensive or controlling. He is driven; he can articulate the vision and what he wants to accomplish. He must be willing to—and want to—work with investors. He wants to get some outside viewpoints and assistance in terms of advice, governance, introductions, and different ways to approach things. And he’s willing to give up some of the control.

“His motivation is to drive great value and take advantage of an opportunity in a timely way because time is of the essence.”

Hockey Stick Principle #71: You must learn to sell your company, not just your product.

VCs also want to know that you can do a very impressive job of selling your company because their goal is for you to either sell it to the market in a big IPO or sell it to a larger firm, and both are very picky and savvy buyers. As one VC partner expressed this concern, “We look for CEOs obsessed with how their product fits in with strategic buyers.” They want to know you’re just as intent on making a good sale as they are.

As iContact founder Ryan Allis, who was very successful at pitching the company, stresses, his job was to sell iContact the business, not necessarily iContact the product. And that is still his job today. “For the most part, I’m selling the company; I’m selling the future annuity-revenue stream and profitability that the company will generate if we execute on our strategy,” Ryan says.

Hockey Stick Principle #72: Transparency is the foundation of investor trust; never engage in obfuscation.

VCs are also drawn to candidness. They do not want you to hype your company to them. That is not the kind of salesmanship that impresses them. They prefer founders who can clearly articulate the challenges the business faces and have formulated good plans for tackling them. Instead of claiming, “Our projections are conservative,” it’s better to be more specific and up front about how provisional your numbers may be, saying, “As with any set of revenue projections, these are informed guesses based upon our current pipeline, lead flow, close ratios, current pricing, expected new salesperson hires, and marketing campaigns we plan to execute on in the next six to twelve months.”

Hire a CFO and Lawyers for Preparation and Negotiation

This list of what drives the valuation of a firm is just a summary overview of key concerns. The complexity of information that VCs will want from you and of the negotiation process demands that you hire experienced professionals to prepare the figures and design a negotiation strategy. You need to hire experienced advisors who know the VC game and can therefore look out for your best interests. VCs are extremely tough and experienced negotiators, and they can be enormously intimidating.

Hockey Stick Principle #73: Don’t show up for the investor negotiation gunfight with a knife; hire experts to join you.

If you haven’t already brought in a CFO with experience in the requisite financial analysis, it’s vital that you either do so at this point or hire one on a consultancy basis. You may worry about the expense, but you can’t possibly go into the process without one. Also, if you haven’t developed one before this point, you must now create a very strong, persuasive business plan. This plan doesn’t have to be one hundred pages long; those are generally overdone. What’s more important is the quality of the content, not its quantity; that is what will impress investors. If you aren’t an MBA or CFO yourself, hiring those skills at this point is critically important.

Bringing in trusted financial expertise will help you get your financial house in order and will verify that you are in the position you think you are before you enter the dragon’s den. Working with highly skilled professionals with a strong track record also lends you clout. As Lisa Falzone of Revel Systems advises, “I think venture capital has a very firm mentality. I would say that it’s about getting one person that is well respected to vouch for you rather than you vouching for yourself.”

You absolutely must also hire an experienced lawyer with many successful negotiations to his or her credit. A venture capital firm’s offer is described in a term sheet, and the agreed-upon provisions are detailed in elaborate final legal documents. But beware of the term sheet! The precise meaning of each provision could have dire implications for your business later on. In addition to describing the investment amount and ownership, a term sheet describes what legal terms you’ll now share with your new financial partner, such as issuing new shares of stock, raising additional money, selling the company, appointing directors to the board, changing the articles of incorporation, entering into contracts that could materially affect the business, participating in legal actions, and settling a legal claim. Term sheets also often state that you’ll devote 100 percent of your work time to the business.

When negotiating with VCs, you must not allow yourself to be bullied by the argument that certain terms are the norm. As Scott Edward Walker, a lawyer who specializes in representing entrepreneurs, says, “All terms are negotiable—no matter what anyone tells you.”112

Pitch-Perfect Pitching

When it comes to doing the actual pitching, though, the focus is all on you. Getting it right is going to take practice, and it’s best if that is not in front of friends and family, because for one thing, they’re going to be inclined to be encouraging and may find offering criticism to you difficult. But more importantly, they probably have little or no experience with VCs. Instead, you need to pitch to real investors. Here are some key tips on how to pitch to VCs:

• Start at the bottom of the list. Try pitching first to VC firms that you already know probably aren’t a good fit. That way, you get practice with real pitching and learn a great deal from your mistakes before you pitch to firms that you’re really targeting.

• Seek advice after each pitch. More than likely, you’re going to get turned down a number of times. Write a list of several standard questions to ask after these meetings to probe into how you can improve your argument and also to explore what connections they might help you make. Some questions to ask them: If you were me, how would you pitch my company to investors? What are the strengths and weaknesses of my pitch and company? Do you know other investors that might be interested in my company? Could you introduce me to them?

• Limit your product demo time. Unless requested otherwise, limit your demonstration to ten minutes. Even if you have an interesting product, do not overestimate the entertainment value of your pitch. These demonstrations quickly become boring, especially for people who attend so many of them.

• Know your audience. Do a great deal of preliminary research before the pitch meeting. Because most VC firms specialize in particular types of businesses, you can figure out a great deal about what they’re going to want to hear from you. Study the start-ups they’ve invested in. Look for commonalities.

• Pitching isn’t a one-way street. You need to select your investors just as much as they need to select you. Ask them questions too, and have some of these questions prepared ahead of time. They will respect you for this rather than be annoyed by it. This is one way in which you can demonstrate your managerial prowess and your basic confidence. Some questions to ask them: What is your culture and background? How do you interact with company CEOs in your portfolio? What were your key contributions to start-ups that were some of your greatest successes? And most importantly, what ideas do you have for growing my business?

• Get them what they need when they need it. As with any sales transaction, follow-up is critical. During a pitch, write down anything the firm asks you to provide and send it promptly. How quickly and completely you respond is a litmus test about how effective a manager you are.

Not only must you prepare well for making a pitch, you should seek the support of some allies when approaching venture firms. You do not want to go into these meetings relying entirely on your own merits. The best way to meet a VC is through an introduction by another entrepreneur or through an investor, banker, lawyer, or accountant.

One last thing to remember when you’re trying to persuade VCs to offer funding for your business is that it isn’t all about the quality of your pitch or even about how impressed they are by you. They know that the success of a start-up isn’t really all about the founder; they will also want to know that a strong management team is in place and that you’ve created an organization that can rise to the occasion of surging growth. So in the next chapter, we’ll consider the essentials of building up a strong team.