The Proven Principles for Achieving Hockey Stick Growth

Launching your own innovative business—one whose product, service, or business model you have invented—and seeing it through to success is a deeply satisfying process. I’ve done it twice, and there’s nothing I’d rather have spent the last fifteen years doing.

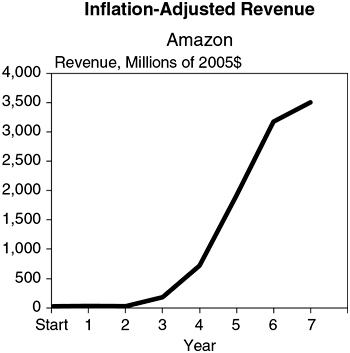

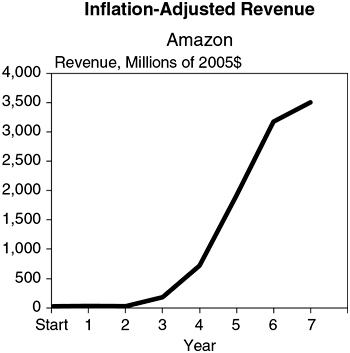

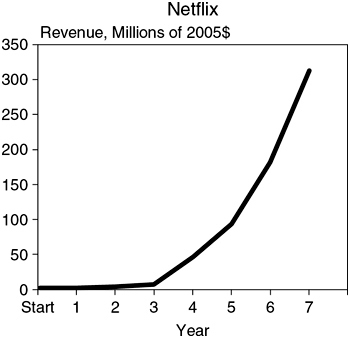

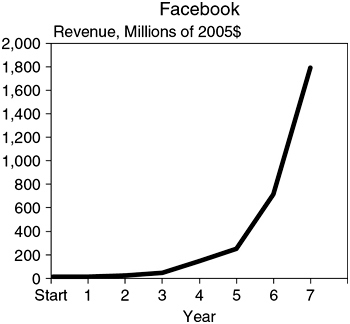

As is true for so many start-up founders, I had no idea how to build a business when I started. I just had an idea and a commitment to making it work. It was a huge challenge, but it was also a highly rewarding adventure. As with so many innovative start-ups, my first company, First Research, which provides industry research reports for sales and marketing professionals, achieved classic hockey stick growth takeoff in which revenue shot dramatically up in a curve shaped like a hockey stick. Hockey stick growth is often characterized as possible only for truly game-changing start-ups, as with Amazon, Netflix, and Facebook, for example.

But I’ve seen the same pattern time and time again as an angel investor and advisor to many start-ups, and my cofounder and I have also seen hockey stick growth with my second start-up, Vertical IQ, which provides industry profiles to banks. In fact, a study I conducted of start-up growth patterns showed dramatically that the hockey stick curve is quite common for successful innovative start-ups, and that’s true for businesses of all kinds and all sizes, not just high-tech dot-coms.

When I plotted the revenue growth of 172 successful start-ups for the first seven years from launch, covering a wide range of sectors from Web leaders like Google and LinkedIn to non-Web businesses like Chobani yogurt, TOMS shoes, and video camera maker GoPro, all but eleven saw hockey stick growth. (If you want to see a selection of the graphs of the businesses I studied, they are available at the book’s Web site: www.hockeystickprinciples.com.)

This shows conclusively that hockey stick growth is exactly what to be aiming for as you launch your own start-up. But if such breakthrough success is so possible to achieve, why is start-up failure reportedly so common? To answer this, I decided to delve more deeply into researching start-up success and failure to determine whether there was perhaps a proven set of best practices for dealing with the many challenges. Are there certain key things that successful founders consistently do that make the difference in their businesses taking off? My research revealed that there are.

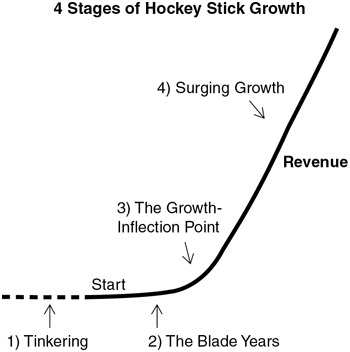

I interviewed successful founders of all kinds of start-ups in depth, getting the details on exactly how they built their businesses, from how they came up with their ideas through to developing them into viable business models, how they designed and developed their products and services, how they launched, and how they built their customer base and sales thereafter. The more I delved into the founders’ stories and examined the growth curves for their businesses, the clearer it became that all successful start-ups go through four major stages of growth, which track along the hockey stick curve, and each of these growth stages—which I call tinkering, the blade years, the growth-inflection point, and surging growth—presents founders with its own distinctive challenges. As I compared the stories of more and more founders and how they faced these challenges, the commonalities between the businesses that succeeded, including mine and my cofounders’, were striking, as were the similarities of the mistakes that were made by founders who failed. The result is that I have identified a set of core principles to follow in each stage of growth, which I call the Hockey Stick Principles. Following them will empower you to move successfully through each stage and to ultimately reach takeoff growth.

The great business analyst Peter Drucker once said about running a successful business, “Management is doing things right … leadership is doing the right things.”1 The founders of start-ups have to do both well; they must constantly determine the right things to do at the right time and also work out the best methods for getting them done. The Hockey Stick Principles show you how to rigorously tailor how you are operating in each stage according to the particular demands of that stage so that you can succeed where so many others fail.

A Closer Look at the Four Stages

The building of every start-up is, of course, its own game with its own specific set of problems to solve. While some founders must grapple with complicated programming, others might have to work out details of manufacturing and supply chain management. Some might wrestle mightily with inventory control and retailing challenges, and some others might struggle particularly with finding the right recipe for online-only sales or with threats to their intellectual property. For instance, the process of creating and marketing a new type of high-tech smartwatch, as the founders of the Pebble Watch did, is quite different in the details from developing a breakthrough new mobile app like Instagram. This is what makes the underlying similarities of the challenges of each stage of the process so hard to discern; every start-up’s story can seem to be unique, and in the fine details, that’s true. But the fundamentals to be grappled with are universals, and having the framework of the four hockey stick stages to guide you will help you to keep these crucial fundamentals at the forefront in the heat of action.

In order to show how broadly applicable the hockey stick stages and the principles to follow for each are—and to help you apply them to your product or service—throughout the book, the stories of real flesh-and-blood founders who started successful companies in a wide range of sectors will be told and will be contrasted to those of failure. This not only makes the book an engaging read, allowing you to think through how you would have dealt with their challenges, but it also helps to showcase that as unique as the product or service your company is offering may be, you will still be grappling with the same fundamental issues as other businesses.

So let’s now take a broad-brush look at the four stages of hockey stick growth.

Tinkering

This is the time during which founders are beginning to explore the viability of their idea. It begins when they start to take action to examine the idea more seriously, and it ends when they fully commit to developing the business.

While this is the least pressured of the stages, because most often the founder hasn’t yet quit his or her day job or committed to a launch schedule, it still presents many tricky challenges, and too many aspiring founders never get beyond this stage. One of the most common mistakes made is that founders waste a great deal of time developing elaborate business plans, which seems so obvious as a must-do but is in fact, as we’ll explore more fully, a terribly misguided action. Believing that you should develop a good business plan on the sole basis of an idea lends support to one of the biggest fallacies about the start-up process: that you’ve got to begin with a good idea and everything will flow from there.

Hockey Stick Principle #1, to be discussed more fully in the next chapter, is: You don’t need a good idea. Viable ideas for start-ups don’t just emerge whole from founders’ brains; they are developed over time. This stage should be a period of actively experimenting with developing the product or service, getting out into the field and soliciting the feedback of potential customers, as well as canvassing suppliers and retailers, testing—and truly challenging—your ideas for the product and all aspects of your business model, and listening carefully to responses. It’s often from this experimentation and critical listening that crucial changes to initial ideas come, which make all the difference in eventual success.

Too many founders are reluctant to discuss their ideas at this early stage and to show actual sample products for fear of competitors copying from them, and too many of those who do solicit feedback do so within an echo chamber of supportive friends and family who tell them what they want to hear. As a result, many founders fail to develop a deep understanding in this period of the market they’re aiming to serve and what the true needs and desires of those they’re targeting are, and they forge ahead with building a product that has no real market. Others accept the inevitable negative feedback they get too readily rather than analyzing it and discovering a deeper truth about how they could improve on their idea. Even if the idea strikes many as brilliant, and funders offer bundles of investment cash on that basis, if the needs and desires of the market haven’t been understood, the product launch will fail.

A great example of a founder who did a masterful job of negotiating the challenges of the tinkering process is Bob Young, who started the $1.5 billion software services provider Red Hat. Young and his cofounder achieved phenomenal success by creating an innovative business model that gave Red Hat’s core product away for free to some customers while charging others for it. Young and his partner went ahead and created their basic product, and Young then went out and tried to sell it, talking with potential customers. This led him to the company’s innovative model. Young listened carefully and critically to all the feedback, and he tweaked the product, pricing, and services the company provided in creative ways that allowed Red Hat to address all the various criticisms raised. He also gave himself time for this discovery process by bringing in cash for the first couple of years with a retail business, so he had no need to take on debt or waste any time chasing funding.

Now consider the story of another software firm, GoCrossCampus, which failed despite raising $1.6 million right from the get-go and garnering major support in the press. Cofounders Brad Hargreaves and Matthew Brimer had created a computer game about which The New York Times wrote, “The game, a riff on classic territorial-conquest board games like Risk, may be the next Internet phenomenon to emerge from the computers of college students.”2 From what I read the founders seemed to believe that raising lots of cash up front was the key to success, so they focused a great deal on this, and very successfully, raising another $300,000 every four months as they kept developing the game. But having taken so much investment capital, they felt intense pressure to launch the product for the start of the 2007 college year, and after they did so, they ran into glitches and had to shut down the site for six weeks. As Hargreaves said in a Business Insider article reflecting on the debacle, “We should have spent the fall working on the project and then launched in the spring.”

Another big mistake was that they tested the game primarily on friends and family, and rather than taking their negative feedback as helpful criticism, they were upset by it, which Hargreaves said interfered with their productivity. They also launched before they had figured out how the company could actually make money from selling the game. The college students they were targeting were, as Hargreaves recalled, “hard to monetize.” They didn’t want to pay for the game, and the founders never figured out an alternative model for earnings. Before long, the company ran out of money and had to liquidate their assets in a fire sale.3

The principles for tinkering that will be introduced in the coming chapters will allow you to avoid all these mistakes and other common ones made in this stage.

The Blade Years

This is the period of time when founders have fully committed to making the business work and are preparing to launch until they hit the growth-inflection point.

This is a bumpy time of highs and lows, during which many founders lose heart or become overwhelmed. They’ve quit their day jobs in order to devote themselves full-time to developing the business, and they’re often not earning enough of a salary to pay their personal bills. My study shows that this stage usually lasts three to four years, during which revenue is often quite low, if any is coming in at all, showing up as the blade part of the hockey stick curve. The lack of adequate earnings leads many founders to focus a great deal of their energy on the quest for investment capital at this early stage, which too many founders think is the only way to fund the development process. They waste valuable time making elaborate pitches to potential funders, which most often fail to impress because they have no tangible results to point to. And if they do raise significant investment capital, as with GoCrossCampus, it often puts undue pressure on getting to market, which leads to its own common trip-ups. Hence Hockey Stick Principle #15: Raise the minimum amount you need to get to launch; financing is scarce and expensive.

A better method for success is to bootstrap during this period and to develop an alternate stream of income. This frees you to throw yourself into what should be the twin focuses of your energy in this stage: developing the market you’ve targeted, or searching for a different one, and simultaneously improving the product or service so that, by getting the combination of market and product right, you break through to fast growth.

Key mistakes made during this stage include spending too much on marketing and sales efforts to try to bring in customers faster, whether by pouring funds into an elaborately planned publicity push and advertising campaign or setting up an expensive sales operation. Often, after a big launch, into which founders have thrown everything they have, sales fail to gain traction, and many founders get stuck, continuing to focus too exclusively on a targeted market and pouring more and more money into the same old efforts, when they should be experimenting with alternatives, no matter how unexpected they may be. To avoid this trap, founders must keep in mind Hockey Stick Principle #33: You have no idea what your market is until you find it.

Many founders also fail to seriously consider further changes to the product during this period. Finding a market may require making a major pivot not only in the targeted market but also in the nature of the product. But here, too, many founders misstep, concluding too quickly that they should pivot when instead more measured tweaking—or developing a better sales and marketing approach for the same targeted market—are the right options. As I will show later, sometimes even just very minor tweaks can make a huge difference in results. Rather than always pivoting when the going gets tough, as we’ll explore more fully, the right approach to making changes in this stage is to systematically interrogate every aspect of your business model and then decide whether to make a major pivot.

A great example of a business negotiating the challenges of the blade years and reaching growth inflection is that of The Climate Corporation, which sells weather insurance to farmers. The firm was founded by two former Google employees, and their initial concept was to sell derivatives—a highly sophisticated form of financial product—that would allow the owners of businesses of all sorts that are regularly hurt by bad weather to protect themselves against those losses. The founders were brilliant mathematical minds, and they created such an impressive basic program that they raised many millions of dollars in funding from their network of friends. But when they launched a fancy Web site and did lots of advertising, they had very few takers.

As we’ll see when the story is told more fully, rather than burning through their cash by increasing their ad spending, they drilled into discovering a viable market, and they pivoted by turning the company into one that offered traditional insurance to serve a good market they identified. After that, their growth took off, and they sold the company to Monsanto for approximately $1.1 billion.4

By contrast, the founders of EventVue never developed a depth of understanding of their target market or branched out to experiment with other markets, and even though they recount that they did make a pivot in the nature of their product, they waited too long to do so and didn’t really commit to the hard work of making that pivot succeed. Also, even though they raised a good amount of funding early, they never created a revenue stream to support further development.

As the founders recounted in a postmortem memo, they originally offered a service that would create a customized social network for specific events, such as a music concert or a business conference. They made such a persuasive case for their idea that EventVue was selected by leading start-up incubator Techstars as one of their ten companies for 2007, and they also raised seed capital of reportedly about $250,000.5 However, after this promising start, they failed to drill into their target market. As they wrote in their memo, “At the time, we did not think about or understand the challenges of getting a lot of conference organizers to use EventVue.”6 And they continued to fail to probe deeply into the market for months and months even though they weren’t getting the sales they’d hoped for, recounting that “we were basically calling on friends of friends who ran events to be our customers, we didn’t learn what event organizers in general wanted or how to acquire them as a customer.”7 They finally pivoted by offering a different service, the idea they hoped would drive more attendees to events. But as they admit, they didn’t do the hard work of verifying that the new product they developed would actually help increase attendance, so they again ran into a wall with the market of conference organizers. They had never really experimented with different markets for the social network product, and they never deeply researched whether or not the new product they created for their original market actually worked. Then they simply ran out of cash.

The Growth-Inflection Point

This is the wild ride of a time when revenue turns sharply upward. It’s an exhilarating stage. At this point, you’ve honed your model, and sales are coming so much more easily. Venture firms and other investors may come calling, offering tantalizing deals that will allow you to leverage this growth momentum and scale your business way up. But this stage also poses many dangers; primary among them is scaling up too fast, so that rather than sustaining strong growth many start-ups crash and burn. Scaling too quickly has been identified as the number-one reason for start-up failure. So much has been said about the need to “go big fast,” but too often this leads instead to going bust fast. In this stage, founders must always keep in mind Hockey Stick Principle #51: Don’t spend lots of money to fuel fast growth until you’re pouring it into a high-performance engine.

The primary job of this inflection stage is to carefully calibrate the growth of your operations so that they are in sync with your growth in revenue. Otherwise, scaling up isn’t really growing; it’s inflating. Too many founders invest too heavily in ramping up staff, purchasing or renting larger office space or manufacturing equipment, and expanding retail space and facilities. Before they know it, their costs have escalated way beyond their continued increase in revenue, and even though they’ve found a good market and are off and running, they’re running out of gas.

Another trap founders fall into during this stage is making changes in a model that’s working well because they think it’s required in order to capitalize on the huge growth opportunity that’s become clear. For example, some businesses may have been relying on Web advertising only, and then they order up a high-ticket TV ad campaign; or if they had sold exclusively online, they decide to open brick-and-mortar stores. Oftentimes, founders think they’re building on their model when in fact they’re perverting it. The push for these changes often comes from investors who have offered tantalizing sums to fuel growth, and founders regularly underestimate the pressure investors will exert and the amount of control over strategic direction they’ve given up for that cash.

One start-up that managed this stage brilliantly is e-mail marketing software services provider iContact. The founders, Ryan Allis and Aaron Houghton, started the company while they were still in college, and they had little business management experience. But after the company’s sales took off in its third year, spiking up from $296,000 in 2004 to $1.3 million in 2005, they kept cool heads and focused tightly on putting the additional cash they made into stoking up sales with their existing model. We’ll later read more about the smart scaling-up methods iContact employed. So well honed was their model as they scaled that they were able to raise more than $20 million in outside capital between 2006 and 2009, and with a great deal more market still to tap, in 2010, they raised $40 million in equity funding. They sold the company in 2012 to public relations software company Vocus, which became Cision, for $169 million.

In contrast, one-time “next big thing” online retailer Fab.com managed this stage very differently. Cofounders Bradford Shellhammer and Jason Goldberg launched the site in 2011, selling carefully selected specialty craft items for the home. Their model was brilliant; they offered the items through flash sales, making deals with the creators of the products, who would determine how many items would be available for sale and would take care of order fulfillment. Fab.com had no responsibility for inventory management, warehousing, or delivery. The founders had great taste in items, and their sales quickly took off. But after they raised over $40 million in outside funding, achieving a market valuation of an astonishing $900 million, they began to make a series of changes in their model that we will discuss in Chapter 5 that led them off the rails. Even having raised so much funding, by October of 2013, just two years after launch, they were forced to sell the company for the bargain price of approximately $15 to $50 million.

Surging Growth

If innovative start-ups manage the growth-inflection stage well, they will proceed into a stage of continuing acceleration of growth. During this period, entrepreneurs come to many crossroads. Their market is exploding, but so is the complexity of managing and leading a larger organization. Meanwhile, alluring offers to buy the company are often made. One way or another, a founder must grapple with the difficult transition from scrappy entrepreneur to corporate manager. He or she has three main choices: remaining CEO by learning how to further professionalize the business; hiring a CEO to manage the business, most often either then taking on another role, such as heading up research and development or becoming chairman of the board; or selling the company. Many founders stumble when making the transition to corporate chief and fail to recognize that they must master the requirements …

The qualities that were so important in taking the risks to launch the business and in bootstrapping and experimenting with new things are less called on during this time, and those of a corporate leader become primary. Too many founders fail to appreciate this and neglect to appoint top-quality managers with first-class experience to take charge of the major functions, instead often hiring from within their personal networks and promoting unqualified people from within.

A founder who managed the transition from scrappy, decidedly un-corporate, and even iconoclastic start-up creator to corporate leader is Mark Zuckerberg. He had no management experience at all before founding Facebook, having dropped out of Harvard to create the company in his sophomore year, and by popular accounts was not a natural public communicator or developer of a strong corporate culture. When first starting out, his business card read “I’m CEO, bitch.” But he has been widely praised for dedicating himself to learning how to become a top-quality CEO. He’s brought in many highly respected upper managers, such as Sheryl Sandberg as COO and former Genentech chief financial officer David Ebersman as CFO. He has instituted appealing and creative compensation schemes to recognize and motivate employees. And while his performance when selling the vision and message of the company was once so much in doubt that Sheryl Sandberg often accompanied him in media appearances, he has now become a polished communicator.8

By stark contrast, the poster child for not making this transition successfully is the founder of Groupon, Andrew Mason. He brilliantly innovated the company’s online coupon business model, leading it to become the fastest-growing start-up in history at that time. But he failed to rigorously institute top-quality standards for financial reporting, even though a skilled CFO could have been brought in to do so. Just before the company’s IPO, in the summer of 2011, the company roiled Wall Street analysts by introducing a new metric it called adjusted consolidated segment operating income, which was all too obviously intended to artificially spruce up the company’s financial performance. The new metric was criticized as “financial voodoo” by The Wall Street Journal. Before long, the company was under investigation by the SEC and facing a shareholder lawsuit. As the public face of the company, in several appearances in the media, Mason was highly controversial, such as one notorious case in which he told a reporter, “Sorry, too much beer.” The company was facing serious challenges to its market share and complaints from many of the businesses with whom it contracted for coupon deals, and at this critical juncture, he failed to step up as a mature leader. He was forced out by the company’s board not long after the IPO.9

Mason’s story speaks powerfully to the necessity of applying the right principles at the right time. His flamboyant and irreverent style was well suited to launching the company and getting to explosive growth but horribly suited for taking it public and managing sustained growth. Successfully navigating the changes in responsibilities and the right approaches for tackling them from stage to stage is difficult for most founders. We’ll examine the cases of a number of founders who managed the transition brilliantly and the crucial requirements for doing so.

The Game Plan

In the following chapters, we’ll dive more deeply into what to expect during each stage of growth, and I’ll introduce the complete set of Hockey Stick Principles that will allow you to master these many challenges and become a start-up champion.

The book is divided into four sections, each dedicated to one of the growth stages, and each chapter of a section is devoted to a core challenge of that stage. Packed with stories of how successful founders managed the four stages, as well as a host of cautionary tales about why other founders failed to do so, the chapters vividly illustrate how to apply the principles no matter what type of start-up you’re launching. I’ve chosen the stories to represent a broad range of product type, sector, business model, and scale—and also because they’re just great stories. They show that the principles apply across the board for all types of business, all levels of market potential, and also all types of founders.

The stories of successful founders and their start-ups differ from one another in many ways. Some of these founders took a shotgun approach, building their businesses extremely quickly, such as Lisa Falzone, who started Revel Systems—the first point-of-sale system delivered on Apple’s iPad—in 2010 with just $30,000 of savings, bringing it to a $400 million–plus valuation as of 2014. Others grew their companies over a long period of time, such as James Goodnight, founder of analytics software behemoth SAS Institute, which regularly makes lists of both the largest privately held companies in the United States and the best places to work. Some businesses have created software products, while others have created manufactured goods, such as Boogie Wipes—which makes a saline-infused tissue for children—cofounded by Julie Pickens in 2007 and sold in a deal to Nehemiah Manufacturing in 2012. Some founders had MBA degrees and lots of experience in the corporate world, such as Doug Lebda, who founded leading mortgage lender LendingTree, while others spurned the corporate life and had no business training, such as Wes Aiken, who founded Schedulefly, which offers scheduling and related services to restaurants. Some were at the very start of their careers when they founded their companies, like Ryan Allis and Aaron Houghton of iContact; others were well established in a professional career, like emergency room physician Graham Snyder, who invented the SEAL SwimSafe device out of a passion for preventing children from drowning. They all started their businesses for different reasons and with different ambitions, but what they all have in common is that they followed the Hockey Stick Principles.

I hope the advice in this book will help you achieve the great success that these and so many other founders profiled in the book have enjoyed.

Let the games begin!