8

Bibliographie classification scheses

Introduction

The three major general classification schemes are DDC, its offspring UDC, and LCC. These will be described in some detail in this section. Two other schemes: BC (and its successor BC2) and CC, will be discussed briefly because of their influence on current theory and practice. At the end of this chapter you will:

understand the structure and principal features of the three major general classification schemes

appreciate the salient contributions to classification theory and practice made by BC and CC

be aware of the arguments for and against modifying published classification schemes

understand the place of special classification schemes.

The three major schemes were all introduced before the ideas of facet analysis were developed. They are thus basically enumerative schemes, though all have some analytico-synthetic features. In the case of UDC these are very extensive, less so with DDC - though DDC has embraced the principles of facet analysis and is incorporating more synthetic features. With LCC they are a minor feature.

The Dewey Decimal Classification

In 1876 Melvil Dewey, a 25-year-old college librarian, published anonymously A Classification and Subject Index for Cataloguing and Arranging the Books and Pamphlets of a Library, with 12 pages of introduction, 12 pages of tables and 18 pages of index. It had three novel features:

Books were to be shelved by relative instead of fixed location. With fixed location (which can still be seen in a few places), books were given a fixed place on a numbered shelf, and any new books on the subject represented by that shelf had to be filed at the end. When the shelf became full, a new sequence had to be started elsewhere. With relative location, the books are numbered in relation to each other and not to the shelves. The whole collection could grow as required, and a more detailed subject specification became possible - Dewey’s 999 classes were a great advance on anything that had gone before.

A simple decimal notation instead of the cumbersome notations (often involving roman numbers) previously used. Indeed, Dewey is said to have thought of the notation first. Certainly the notation was an important factor in the early and continued success of the scheme.

A detailed subject index, made necessary by the detail of the classification.

The second edition of 1885 established three further principles:

Decimal subdivision: the first edition used the decimal point only to introduce a book number. This greatly increased the ability of the scheme to support specific detail.

Integrity of numbers: Dewey had made some quite sweeping relocations in the second edition, and to sugar the pill announced that future editions would expand but not relocate: a policy that was followed until 1951. This policy, however reassuring to users and potential users, inevitably meant that the structure of the scheme became more and more outmoded over time.

Synthesis, in the shape of (a) a table of ‘form divisions’ representing some of the common facets, which could be appended to any number; and (b) ‘divide like’ instructions, the forerunner of the present ‘add’ instructions, where all or part of one number may be added to another in order to specify an extra facet.

By 1951 it was clear that the policy of integrity of numbers could not be maintained, but that each new edition would have to radically restructure one or more classes. Complete revision has to date been applied to: 546 and 547 Inorganic and Organic chemistry (sixteenth edition, 1958); 150 Psychology (seventeenth edition, 1965); 340 Law and 510 Mathematics (eighteenth edition, 1971); 301-307 Sociology and 324 Political process (nineteenth edition, 1979); 780 Music (twentieth edition, 1989); and 350-354 Public administration, 570 Biology, 583 Dicotyledons (twenty-first edition, 1996). These complete revisions were formerly known as phoenix schedules. Also, classes may be extensively revised, keeping the main outline but reworking subdivisions. 370 Education and all the rest of 570-590 Life sciences were thus revised in the twenty-first edition, and 001-006 Knowledge, systems and data processing in the twentieth; 004-006 has had to be further revised and expanded in the twenty-first edition.

Schedules

Division of classes

With DDC the notation is everything. This may seem an odd way to start a discussion of the division of classes in DDC, but the evidence is that Dewey fitted his classification to the notation rather than the other way round. The magnificent simplicity of a pure numeric notation is achieved at the cost of the most tightly constricted notational base of any classification. Each stage in the subdivision of the universe of knowledge permits only nine divisions. A three-digit notation allows for only 999 classes, and Dewey used them all. As the universe is not organized on regular decimal lines, it is inevitable that each 1-9 subdivision will more often than not include topics from more than one facet or subfacet With very few exceptions, classes are divided top-down on the enumerative principle. This again has resulted in many classes being divided according to more than one principle of division at a time. This is further discussed below.

Another way of saving notational space is the use of pseudo-hierarchies. One class is used as an umbrella heading for a miscellaneous collection of loosely associated topics. Some examples are:

380 |

Commerce, communications, transportation |

387 |

Water, air, space transportation |

646 |

Sewing, clothing, management of personal and family living |

646.7 |

Management of personal and family living. Grooming |

629.28 |

[Vehicle] tests, driving, maintenance and repair. |

In a few places the original division of classes omitted steps in hierarchies and left no space in the notation for a necessary broader term to be added later. One instance is the sequence 385-388, which denoted rail, canal, sea and land transport without providing a place for transportation generally. For some years a niche was found at 380.5, which preserved the general-to-special order but introduced a yawning gap between transportation and its subdivisions. Recently however, transportation generally has been classed at 388, sacrificing general-to-special in order to keep the subject together. Prose literature is another instance where no provision was originally made: it is found in a number of places (808.888, 818.08 etc.) but always at the end of the sequence of prose forms (essays, letters etc.).

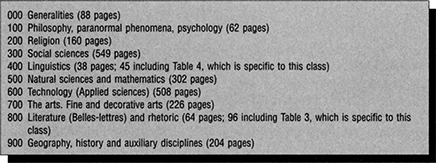

Figure 8.1 DDC Main Classes

Main classes

Advances in knowledge over the past century and a quarter have made an unequal development of the main classes inevitable. Figure 8.1 names the classes and gives an idea of their relative sizes. The classes are based on disciplines, with occasional exceptions, notably 770 Photography that includes both technical and artistic aspects.

Facets

Dewey himself had only an inchoate awareness of facets. Consistency in facet structure tended to be subordinated to the notation. Sometimes the notation lent itself to a coherent facet structure, as in classes 400, 800 and 900. More often it did not, causing the facets to be jumbled together. In 370 Education we find:

371 Schools and their activities (itself a hotchpotch of assorted facets with Special education tagged on at the end)

372,373,374 Stages of education: elementary, secondary, adult - with Higher education separated from these at 378

375 Curricula

379 Public policy issues in education.

Where there is notation left at the end of an array, it may be used for another array with a different principle of division. 720 Architecture has already been mentioned: the arrays are:

721 Architectural structure

722-724 Architectural schools and styles

725-728 Specific types of structures

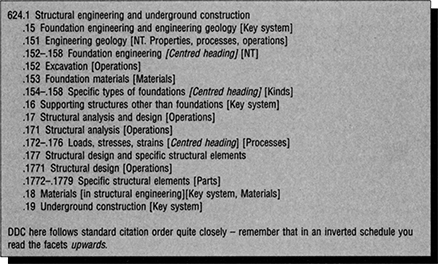

Figure 8.2 Facet structure and centred headings in DDC class 624.1

729 Design and decoration of structures and accessories.

In many places some kind of order is imposed by the use of centred headings, which serve as facet indicators, showing where a facet occupies a spread of notation; 722-724 and 725-728 are examples. Figure 8.2 is a more thoroughgoing example, mapping the implied facet structure onto the schedule.

Since the eighteenth edition determined efforts have been made to regularize the facet structure. Some classes have been completely revised. Elsewhere, ambiguities in the facet structure are dealt with in one of the following ways:

‘Add’ instructions, which always make clear the citation order. In DDC20 we found 370.11 Education for specific objectives, and 372 Elementary education, with no indication of where to class a work on elementary education for specific objectives. DDC21 has provided a new class 372.011, with an ‘add’ instruction to add to this number the subdivisions of 370.11. Thus, 370.115 denotes Education for social responsibility, and Elementary education for social responsibility will be classed at 372.0115.

Preference instructions, which indicate which facet is to be preferred and which is to be ignored. Class 155 is Differential and developmental psychology; 153.9 is Intelligence and aptitudes with the instruction: Class factors in differential and developmental psychology that affect intelligence and aptitudes in 155. In 624.1 (see Figure 8.2), 624.17723 is Beams and girders, and 624.1821 Iron and steel. There is an instruction at 624.182: Class specific structural elements in metal in 624.1772-624.1779, so that Structural steel girders would be classed at 624.17723.

Subfacets or arrays

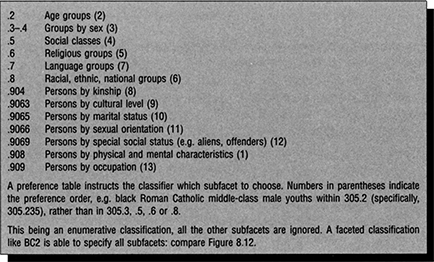

Arrays were given cavalier treatment by Dewey, and later attempts to tidy up the structure have been variably successful. The example in Figure 8.3 shows part of Sociology, which was completely revised in the eighteenth edition. 305 Social groups has 13 subfacets (Figure 8.3)

Most structural problems in DDC are hangovers from Dewey’s original assignment of topics to classes. Some classes, notably 400 Language, are quite consistently constructed. The schedules that have been completely revised also have a far more regular structure, though the degree of synthesis varies greatly: 780 Music is almost fully faceted (to the extent that users are said to be put off by it); 340 Law and 350-354 Public administration allow a high degree of synthesis. 150 Psychology, 301-307 Sociology and 510 Mathematics on the other hand are thoroughly enumerative. Editors of DDC have to tread a very fine line between what revisions are theoretically desirable and what users are prepared to accept 370 Education has been extensively revised in the twenty-first edition, but has retained many of its structural anomalies. While there is no shortage of models of good classification structure in education, to incorporate them would have forced users to make hard decisions on whether or not the extensive reclassification involved is worth the candle. Better a half-hearted revision than one that nobody has the resources to adopt.

Figure 8.3 Subfacets in DDC class 305 Social groups

Citation order

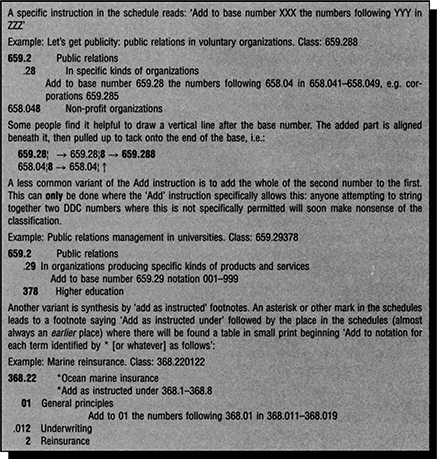

Many of the vagaries of DDC’s citation order have already been examined. However, to correct any impression that all is chaos, it must be stated that the schedules have about them a sturdy pragmatism reinforced by an awareness in recent editions of classification theory. Time and again it is possible to find synthesis and standard citation order. More and more use is being made of synthesis by means of ‘add’ instructions (see Figure 8.4), and in nearly every case the number to be added comes earlier in the schedules - a sure sign that, intuitively or consciously, schedule inversion is being applied.

Figure 8.4 Synthesis by means of ‘add’ instructions

‘Add’ instructions are applied ad hoc (though the principle involved in dropping initial digits is very close to BC2’s). More systematic synthesis is provided through the auxiliary tables in Volume 1 of the schedules. These comprise:

Table 1: Standard subdivisions, which can be applied to any number from the schedules. The oldest of the auxiliary tables, covering the common facets of form and subject. The sequence is chaotic, reflecting the practical difficulties of undertaking a thorough revision.

Table 2: Geographical areas etc. The longest by far of the tables. Typically (but not invariably) applied after -09 from Table 1.

Tables 3 and 4 are special auxiliary tables for use with class 800 Literature and 400 Languages respectively.

Tables 5 (Racial, ethnic and national groups), 6 (Languages) and 7 (Groups of persons) can only be applied where instructed.

Notation

Dewey Decimal Gasification’s notation is at once its greatest strength and its greatest weakness. The concept of numbers used decimally is simple and universally understood; but at the same time DDC’s constricted base and lopsided allocation have led to many excessively long numbers. Another recurring result of the short base is the use of -9 as an overspill class for ‘other’ topics. This is very common indeed. Examples include:

290 |

Comparative religion and other religions |

299 |

Other religions |

629 |

Other branches of engineering |

679 |

Other [manufacturing] products of specific materials |

759.9 |

[Painting and paintings of] other geographic areas. |

Even worse is DDC’s practice of allowing the notation to dictate the order of subjects. Instances have already been given. In some places the notation even dictates the citation order. In particular, DDC’s notation cannot satisfactorily accommodate an open-ended list of named persons, so individuals as subjects can only come at the very end of the citation order. In 800 literature it is impossible to subdivide works by or about individual authors (other than by a local adaptation of the optional table for Shakespeare at 822.33). The revised 780 Music had as its main model Coates’s (1960) British Catalogue of Music Classification. Here, composer was the primary facet for treatises on music; but 780 has been unable to follow this, except as an option at 789.

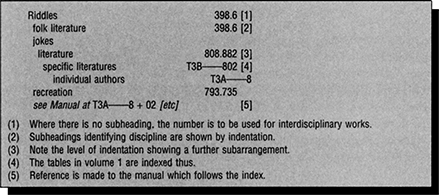

Figure 8.5 DOC Relative index

Alphabetical Index

Dewey Decimal Classification’s index is called a relative index: originally, it seems, because it indexed the new relative as opposed to fixed-place classes; but latterly because it relates subjects to disciplines. Figure 8.5 shows a sample index entry.

There are also see-also references to synonyms and broader terms, but only where three or more new numbers are to be found.

The CD-ROM version Dewey for Windows has a fuller index than the printed index. Nevertheless, the index does not - could not - claim to be exhaustive. Indeed, DDC’s summary tables make it unnecessary to use the index except in the most intractable cases. There are three summary tables of the whole classification, showing the ten main classes, the hundred divisions, and the thousand sections. These appear at the beginning of Volume Two. They are supplemented by summaries at the beginning of each of the ten main classes and their divisions, and additionally as required - complex sections like 616 Diseases or 621 Applied physics may have up to six summary tables each. It is sound practice for classifiers to classify from the schedules as far as possible, using the excellent guiding and summary tables, and to keep the index as a last resort. Bibliographic databases in USMARC format, which have both DDC classmarks and LCSH headings, offer another approach, using LCSH as an entry vocabulary to DDC classmarks.

Organization, Revision and Use

Control of the scheme was assigned by Dewey himself to the Lake Placid Club Educational Foundation, a not-for-profit body which he set up ‘to restore to helth [síc] and educational efficiency teachers, librarians and other educators of moderate means, who have becum [stc] incapacitated by overwork’ (Dewey Decimal Classification, 14th edn, p. 48). (Simplified spelling was one of Dewey’s many interests.) The club owned Forest Press, DDC’s publisher, which gave the scheme a sound financial footing. After some vicissitudes an editorial office was established within the library of Congress, ensuring both literary warrant for the scheme and the inclusion of DDC class numbers in USMARC records. In 1988 the Forest Press was sold to OCLC, and editorial work is now done by the library of Congress under contract with OCLC Forest Press. There is a broadly based Editorial Policy Committee, which includes members from Canada, Australia and the UK, and advises the editorial team. Other experts are also consulted as required. Dewey Decimal Classification’s literary warrant has been improved through becoming part of OCLC, as OCLC’s Online Union Catalog is now accessed electronically as part of the revision process. This, being based on a very wide range of working collections, gives a better idea of the range of titles that libraries actually acquire than could be obtained from a single legal deposit collection.

The schedules are published in four well-designed volumes. A Manual, containing detailed class-by-class advice for the classifier, information on major revisions, and explanation of classification policy and practice, is included in the fourth volume, following the index. New editions are published every seven years. One or two major divisions are recast completely, with piecemeal alterations elsewhere. The major revisions in the current (twenty-first, 1996) edition were described above. Advance notice of changes is published annually in Decimal Classification Additions, Notes and Decisions, abbreviated to DC&, which is distributed to subscribers. The DDC database does include additional information including a wider range of index entries. These appear in the CD-ROM version, Dewey for Windows - a fine tool for the practising classifier, but too complex for those learning the scheme.

A single-volume abridged edition is published alongside every full edition, currently the thirteenth Abridged. There is also a further abridgement: Dewey Decimal Classification for School Libraries. Translations into eight foreign languages are available (most recently Russian), and into at least 30 languages if translations no longer current are included. Although libraries may classify new stock by the latest edition of DDC, earlier editions remain important because many libraries are reluctant to reclassify, and thus leave stock classified by earlier editions long after they have been superseded.

The use of DDC in the British National Bibliography has been important in establishing DDC in British libraries. The British National Bibliography began publication in 1950, and from 1971 has been produced from the UKMARC database. Normal practice is to apply the latest edition of DDC from the January after its publication. There has also been some retrospective conversion of earlier records. There is now a USMARC format for classification data, which incorporates fuller information about DDC classmarks than was previously available. This includes:

a history of changes between editions, making it easier for users to track relocations

the components of synthesized numbers, making it possible to carry out machine searches on classes formed by ‘add’ notes. Thus in the examples in Figure 8.3 above, a search on 658.048 Non-profit organizations could be made to lead to 659.288, which is synthesized from 659.28 and the final digit of 658.048.

a field for centred headings, making it possible to systematize the hierarchical broadening or narrowing of machine searches on DDC classmarks.

These developments are a practical result of the link-up between DDC, the library of Congress and OCLC, and help to ensure the continued success of DDC. In other respects, editorial policy is concentrating on:

user convenience: making the schedules easier to apply

regularization: the gradual elimination of irregular developments of standard subdivisions which occur at a number of places throughout the schedules

‘faceting’: the increased use of notational synthesis

ensuring that terminology is kept up to date, for example by replacing ‘physically handicapped persons’ with ‘persons with physical disabilities’

catering for international needs, e.g., by reducing the American and Christian bias in the classification, and by expanding the area tables and the historical and literary periods for a number of countries.

Library of Congress Classification

The detailed classification scheme of the library of Congress was occasioned by the library’s removal to new premises in 1897. The scheme consists of 21 main classes set out in over 50 volumes. Publication began in 1899 and was virtually complete by 1910 - apart from class K Law, publication of which did not commence until 1969 and was not completed until 1993. There are revised editions of most classes (Q Science is in its seventh edition). Recent editions are published in the USMARC format for classification data, and the full schedules together with LCSH are available as Classification Plus on CD-ROM.

The scheme’s name describes it precisely: it is the classification of the library of Congress. It exists to serve the needs of that body. It was developed, under the general editorial direction of the librarian, Herbert Putnam, and his Chief Classifier, Charles Martel, on a class-by-class basis by the staff of the library’s subject departments, who also implemented the classification. It was, and is, an in-house classification. However, as the classification of the world’s largest library, its suitability to other large academic and research collections was soon recognized, and was greatly advanced by the library’s decision in 1901 to make its printed catalogue cards available for sale to other libraries.

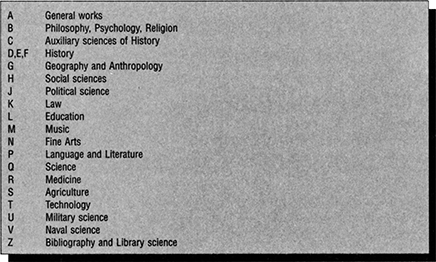

Schedules

The scheme was based on the long defunct Expansive classification of Charles Ammi Cutter. Its main classes (Figure 8.6) are clearly tailored to the needs of the LC, as they were perceived a century ago. Like everything else about LCC, the order of the main classes is thoroughly pragmatic, avoiding the idiosyncrasies of DDC. Each class was compiled separately, and could be used independently. It follows that the classification is almost entirely enumerative, with much repetition of detail, making the schedules very bulky in hard copy.

Classes are divided in a broadly hierarchical manner; but as the scheme was compiled piecemeal at a time when classification theory barely existed, one must not expect the consistent application of either hierarchies or a facet structure, even within a single class. As the most enumerative of all the schemes, LCC can only be learnt by practice. It cannot be learnt by the application of principles, because there are none, library of Congress Classification’s great strength is that every class exists because subject specialists have perceived the need for it, and the order and detail of the classes have been developed, again by specialists, to meet the requirements of an exceptionally large working collection operating under exacting conditions. There are a number of recurring themes, including:

Figure 8.6 LCC main classes

A tendency to file common form and subject facets before general works on a topic. A common sequence (derived from guidelines laid down by Martel) is some kind of variant on:

- Periodicals, Societies

- Collections, Dictionaries

- Theory, Philosophy, Congresses

- History

- General works

Alphabetical subdivision - which purists would object is the negation of classification - is frequently used, the precise method being by Cutter numbers. These allow individual classifiers great flexibility, provided that sufficient authority control is exercised to avoid cross<:lassification. For example, class HJ4653 Income tax - United States - Special, A-Z has subdivisions that include .C3 Capital gains and .E75 Evasion. Which subdivision is to be used for evasion of capital gains? If a title is published on tax avoidance, how do we know not to create a new Cutter number for it under A? In these respects, the success of LCC depends on its being based on a single authoritative institution that applies authority control on behalf of all other users.

A variable amount of ad hoc synthesis, which never has any application outside its main class (so there is no one table for the common facets). Methods vary from elaborate tables - class P has a truly wondrous table of subdivisions under individual authors, separately notated according to the amount of notation allocated to an author - to brief one-line instructions to divide one spread of numbers in the same way as another.

Notation

The general pattern of LCC’s notation can be observed in the examples above: one or two (very occasionally three) capital letters followed by up to four digits used numerically rather than decimally. Hospitality is achieved by leaving gaps in the notation. Where these have been filled, the notation is then expanded decimally. It is all very clear and workmanlike, like the numberplate of a car. The use of Cutter numbers adds to the complexity of the notation, however. There is also an official manual giving guidance on shelf-listing.

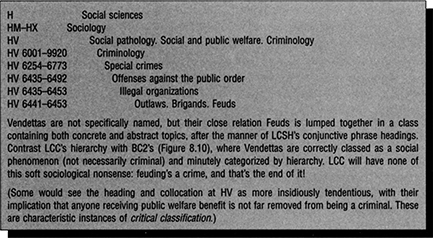

Figure 8.7 LCC sample topic: Vendettas

Classmarks assigned by the library of Congress and appearing in USMARC records always include the full shelfrnark, so that every LCC classmark ends with a Cutter number - or, in the many places where A-Z topical subdivision is prescribed, with two in succession. Many libraries perceive this as an advantage, as they can use library of Congress shelfrnarks as they stand, thus eliminating one stage of book preparation. Some American libraries have migrated from DDC to LCC because of this.

Alphabetical Index

For many years there was no official comprehensive alphabetical index, but only the indexes to each volume. library of Congress Subheading served as a rough and ready index, however, as many headings have relevant LCC classmarks. The CD-ROM has a comprehensive index.

Organization and Revision

As the in-house classification of a huge legal deposit library, LCC assigns new classmarks as the need arises. A list is published weekly in the library’s Information Bulletin, and the CD-ROM is updated annually. Revision is thus continuous, unlike DDC’s. Radical revision of individual classes is very much the exception. The following official manuals are published: Subject Cataloging Manual: Classification; Subject Cataloging Manual: Shelflisting, LC Cutter Table. These are available electronically on the Cataloger’s Desktop CD-ROM, along with other publications on cataloguing topics. The CD-ROM is designed to be used in conjunction with Classification Bus.

The scheme is primarily used by LC itself and by other extensive research collections such as large academic libraries, mainly North American but also in other English-speaking countries, including a significant minority of British university libraries. The resources behind the scheme, and the size of the collections that currently use LCC, are sufficient to ensure its stability throughout the foreseeable future. United Kingdom MARC records currently include LCC classmarks, though with some gaps in the case of retrospective UKMARC records. They do not however include shelfmarks (i.e. Cutter numbers) for individual items.

Other General Classifications

Universal Decimal Classification

Universal Decimal Classification emerged from an attempt in 1894 by two Belgians, Paul Otlet and Henri LaFontaine, to commence the compilation of a ‘universal index to recorded knowledge’. A classified rather than an alphabetical approach was necessary in the index because of the many languages involved, and because an internationally acceptable notation was important. The Dewey Decimal Classification was already in its fifth edition, and Melvil Dewey’s permission was obtained to extend the scheme. A conference in 1895 established the Institut International de la BMographie (IIB) to be responsible for the index.

The first edition of UDC was published in French between 1904 and 1907. The First World War and the unfavourable climate after it led to the demise of the index, but UDC continued with a second edition in French and a third in German. The IIB eventually became the Fédération International d’Information et de Documentation (FID). The British Standards Institution, the official English editorial body, published an abridged English edition in 1961. Publication of a full English edition had begun in 1943 but was not completed until 1980. Since 1992 all rights and responsibilities for UDC have been vested in the UDC Consortium, representing various international and national organizations. There now exists a machine-readable Master Reference File containing some 60 000 classes (compared with 220 000 classes in the full editions), from which the International Medium Edition, English Text, second edition was published in 1993. There are also editions in various combinations of Full, Medium and Abridged in around 20 other languages - French, German and English are UDC’s official languages. A revised edition of the official Guide to the Use of UDC was published in 1995.

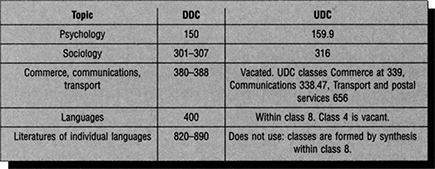

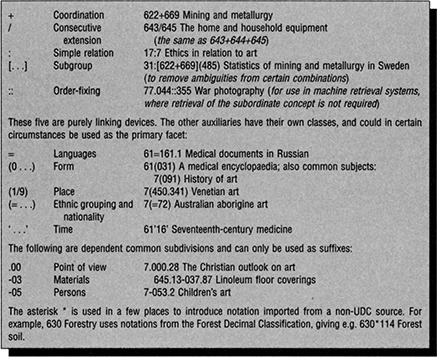

Figure 8.8 Principal differences between DDC and UDC schedules

Schedules

The overall outline of the schedules follows DDC, with the main differences shown in Figure 8.8.

It will be apparent from this that UDC’s attitude towards disciplines is more relaxed than DDC’s. The schedules and notation are largely hierarchical, though hierarchies are less clearly indicated than in DDC. There is no indentation. Bold type is used, but is applied mechanically to notations of six digits or fewer, the shorter the number the larger the typeface. In the Medium edition many classes have headings describing aggregates of topics, e.g., 675.25 Mechanically treated leathers. Including: Embossed leather. Buff. Perforated, punched leather. The Full edition provides subclasses for each of these. The schedules include some pre-coordinated classes, for example:

341.345 |

Internment of military personnel in neutral countries |

551.588.5 |

Influence of ice on climate |

664.71 |

Milling of wheat and rye |

664.782 |

Processing of rice. Rice milling |

664.784 |

Processing of maize. Maize milling (corn milling) |

664.785 |

Processing of oats. Oat milling |

While many enumerated compounds do occur, the principal means of pre-coord-ination is by synthesis. Within the schedules, ‘special auxiliary subdivisions’ are frequently to be found. These often indicate a Processes or Operations facet, and are introduced by .0 (less frequently by a hyphen or an apostrophe). They apply only to their class. For example, under 636 Animal husbandry, 636.082 is the special auxiliary for the breeding of animals. 636.1 denotes Horses, and 636.16 Ponies, which would give 636.1.082 and 636.16.082 for the breeding of horses and ponies respectively. In a few places an equivalent of DDCs ‘Add’ instructions is to be found, indicated by = for example 378.18 Student life, customs etc = 71.8 - classifiers have to work out for themselves which part of the number to bring across. There are also ten Common auxiliary tables (Figure 8.9).

Figure 8.9 UDC Common auxiliary tables

Most of the auxiliaries can if required be repeated or combined with one another, so a high degree of synthesis is possible. The colon is the general purpose relational indicator: when UDC was used to compile subject indexes, before machine retrieval became the norm, it was common to find hugely lengthy notations containing four or more facets strung together with colons.

Uniquely among general classifications, UDC allows the individual user a large degree of autonomy in selecting the citation order. Standard citation order is officially recommended, however, and in many places it is built into the schedules through the special auxiliaries. There is an obvious need for the individual user to follow a consistent citation order, and the maintenance of an authority file is particularly important.

UDC contains a number of devices to enable a user to modify standard citation order. Notation may be reversed round the colon, e.g., 17:7 (Ethics of Art) may be expressed as 7:17 making Art rather than Ethics the primary facet. Any auxiliary that has both an opening and a closing notation can be moved to other positions, e.g., instead of 343(410.5) Criminal law - Scotland, a user may prefer 34(410.5)3 Law - Scotland - Criminal, to keep all Scottish law together.

UDC’s filing order is complicated by the range of non-alphanumeric characters in the notation, and by the possibility of many auxiliaries being used independently, so that a class number could conceivably begin with a bracket, equals sign or double-quote. That aside, the coordination and extension symbols + and / widen the scope of a class, so they file before the simple class number. Thereafter, the filing order is (broadly): (colon), then = (equals), then (…) (bracketed auxiliaries), then ‘…’ (double quotes). This is not an exhaustive listing: the Guide has a mind-boggling table with over 20 entries, including the sequence .00 -0 -1/-9 .0 which is equally incomprehensible to machine and human filing.

Notation

Though based on DDC, UDC’s notation is far more complex, thanks to its non-alphanumeric auxiliaries. Thanks also to these, the finer aspects of showing the order of classes are not always apparent There are other differences from DDC. Main classes and their divisions are not filled out with zeros to a three-digit minimum: Technology and Agriculture are 6 and 63 respectively. Where final zero is used, it is significant: 630 denotes Forestry; (41) is the auxiliary for the British Isles, (410) for Great Britain as a political entity. A point is inserted after every third digit of the notation, as 629.454.22 Railway sleeping cars.

The notation is completely hospitable through the use of decimal expansion. As UDC has been largely developed for use in scientific and technical contexts, the allocation of the notation is even more skewed than DDC’s, and classes 5 and 6 comprise almost two thirds of the schedules. For more specific subjects the notation can be extremely long.

Alphabetical index

The single-volume Abridged and two-volume Medium editions have their own complete indexes. As with DDC, classifiers are recommended to work primarily from the schedules, and to use the index as a check on the validity of a selected number or the locations of related classes. In particular, many UDC numbers are obtained by synthesis, and the index does not show synthesized numbers.

Organization and revision

UDC’s revision structure has in the past been notoriously slow. The setting up of the UDC Consortium, together with the machine-readable Master Reference File, can be seen as measures to streamline the revision process. Much work remains to be done in ironing out UDC’s anomalies to make it entirely suitable for machine searching. There are currently some interesting projects for developing UDC for computer retrieval, and prospects for the successful rejuvenation of the scheme do appear brighter than in the fairly recent past.

Prior to the 1970s UDC was frequently to be found in large card indexes in special libraries and sometimes in abstracting and indexing tools. Computer-based indexing systems have largely rendered obsolete UDC’s detailed indexing function (which essentially is why development is now concentrating on the Medium rather than the Full editions). UDC remains very popular for shelf classification, particularly in the libraries of continental Europe. It is also used to arrange various bibliographies and indexing services (for here the length of the notation is less of a problem than on the spines of books), including Walford’s Guide to Reference Material, the British National Film and Video Catalogue, and the national bibliographies of over 20 countries. The omission of UDC class numbers from MARC records of North American and UK origin is a serious limitation.

Bliss Bibliographic Classification

Henry Evelyn Bliss (1870-1955) made classification his life’s study, and wrote two major theoretical works before his classification was published in stages between 1940 and 1953. Though published by the H. W. Wilson Company, his work had little impact in the USA, but had a small but enthusiastic following in Britain and elsewhere, particularly in the specialist fields of education, social welfare and health. A Bliss Classification Association was formed in Britain to sustain and develop the classification, and the decision was made to undertake a major revision on analytico-synthetic principles, using and developing the work of the Classification Research Group towards the elusive goal of a completely new general classification scheme. Bliss’s original classification had many synthetic features, but was essentially enumerative in structure, and chiefly notable for the care taken over the order of classes. The revision (BC2) was to retain much of this macrostructure, but otherwise is effectively a new classification. It is this version that is discussed here. The schedules are being published class by class. Publication began in 1977, and is still not quite complete.

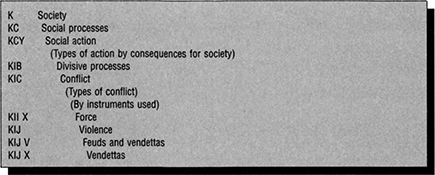

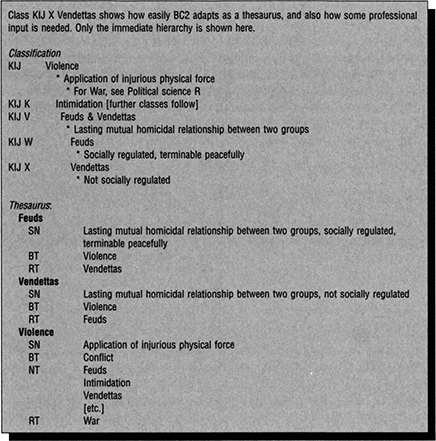

Figure 8.10 BC2’s hierarchy for Vendettas

Schedules

As BC2 is entirely faceted, only simple concepts appear in the schedules. The schedules are rigorously hierarchical (Figure 8.10).

While the notation is not hierarchical, hierarchies are clearly indicated by indentation and by summaries at the head of every column. Subfacets are shown within parentheses.

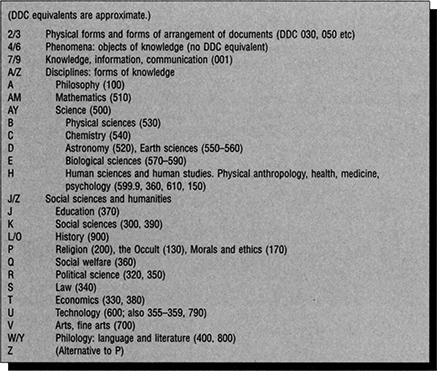

BC2’s basic citation order is Disciplines - Phenomena. Phenomena that are treated in a non-disciplinary manner are given a numbered notation, to make them file before the disciplines. The main classes are little changed from BC, and continue to embody Bliss’s principles of following the ‘educational and scientific consensus’, placing general before special, ‘gradation in speciality1, and the collocation of related subjects. Figure 8.11 shows the main classes, with approximate DDC equivalents.

The schedules are relentlessly faceted, and all facets and subfacets are carefully indicated. The complexity of the facet structures of many classes can give the schedules a daunting appearance, and a clear head is needed when approaching them from cold. For example, the facet formula for class K Society is:

Collectivities (KLK/KV)

Parts and properties (KLK KW)

Institutions (KK/KLC)

Social processes (KC/KJ)

Environmental bases (KA/KB)

Figure 8.11 Order of main classes in BC2

Operations on phenomena (KA/KB)

Common facets (K2/K9)

Even in a ‘soft’ science like sociology, many of the elements of standard citation order are discernible. As always, the order of the schedules is the reverse of the citation order.

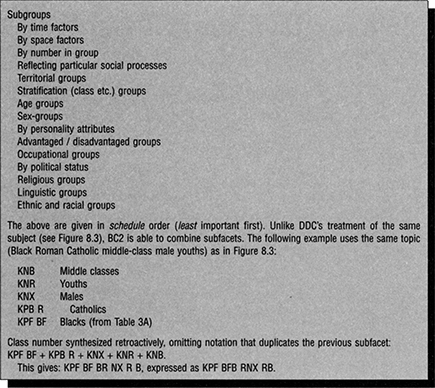

Figure 8.12 below gives an example of BC2’s subfacets. For an example of subfacets within a single classmark, see the breakdown of class KK J Vendettas in Figure 8.10.

Notation

BC2’s notation uses both numbers and letters (capitals only; BC used both capitals and smalls). As has been seen, numbers and letters are used together in the listing of main classes. Otherwise, numbers are used only as facet indicators for the common subdivisions:

Figure 8.12 Principal subfacets for social groups (KLM-KV) in BC2

2 |

Physical form |

3 |

Forms of presentation and arrangement |

4/9 |

Common subject subdivisions |

These are the only facet indicators; the standard method of building classmarks is by retroactive notation. The notation is remarkably brief, and can pack a goodly number of facets into a small compass. Brevity is assured by means of:

a long notational base

sensible allocation of notation to the classes (with the reservation that out of deference to BC too much space is allocated to History and not enough to Science and Technology)

a non-hierarchical notation

absence of facet indicators.

For easier use, the notation is split into groups of three characters. An (extreme) example of BC’s synthesis in action is given in Figure 8.12.

For anyone used to DDC, BC2 has some oddly notated hierarchies. Being non-hierarchical, the notation is required only to show the order of topics. The length of the notation reflects the estimated literature on a topic, and not the degree of subordination. Thus, in the above examples, AY Science appears to be - but is clearly not - a subdivision of A Philosophy, and its first subdivision - B Physical sciences - has a shorter notation.

Alphabetical index

As with UDC, BC2’s indexes show simple concepts only. Each volume of the schedules has its own index: there is no general index. It is thus up to the classifier to decide on an item’s main class before it is possible to have recourse to the index. Every volume contains two outline schedules of the whole classification; the second outline has around 100 classes: much the same level of detail as in DDC’s second outline.

Organization and revision

Both BC and BC2 have been dogged throughout their lives by a chronic lack of resources. BC2 was conceived at a time when there was an enthusiastic following, at least in Britain, for the idea of a highly specific general classification that would form the basis for all forms of information retrieval. A generation later the world has moved on, and BC2 is still only half-published. Its intrinsic qualities may make it the benchmark by which other classifications may be judged, but quality is not in itself enough to attract users and ensure its future. Besides being ill resourced, the physical production of many of the schedules is user-unfriendly, and considerable intellectual effort is required to become fluent in using the schedules. Most importantly today, BC2 classmarks do not appear on centrally produced MARC records.

Paradoxically for a classification calling itself Bibliographical, it may be that BC’s future is to be used predominantly not as a library classification but as a quarry for others to mine. More than any other general classification, BC2 resembles the systematic display of a thesaurus. Its specificity is such that the great majority of its headings can be used as they stand as thesaurus descriptors, and reorganizing the semantic relationships for a thesaurus is largely a mechanical exercise (but by no means altogether so - see Figure 8.13).

As well as being a potent source for thesaurus compilers, BC2 with its immense detail and regular and explicit structure would lend itself to machine manipulation better than UDC, and there have been suggestions that the development of UDC could borrow some leaves from BC2’s book. (There is already some collaboration with UDC.) More generally, the study of classification schedules is recognized to be an excellent starting-point for anyone who needs to learn how a subject is structured, and the detail and rigorous analysis of BC2’s schedules make it especially useful in this respect.

Figure 8.13 Adapting BC2 as a thesaurus

Colon Classification

The CC devised by S. R. Ranganathan is little used outside the Indian subcontinent and in the Western world is chiefly of historical interest for its development of facet analysis. First published in 1933, subsequent editions have introduced quite drastic changes. The current edition is the seventh (1987, and still lacking an index).

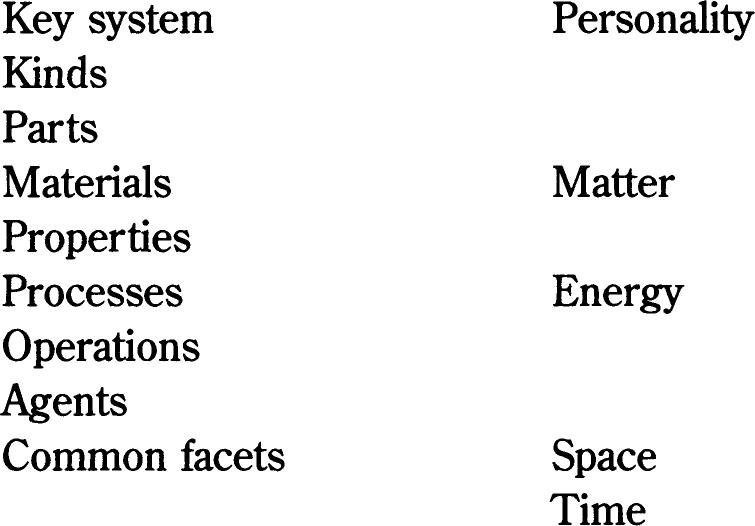

CC’s facet formula is simple, sturdy and hauntingly memorable: PMEST, i.e. Personality, Matter, Energy, Space and Time. Personality is (broadly) Key system; Matter is Materials; Energy is Processes and Operations; and Space and Time are two of the common facets. Mapping these onto standard citation order gives:

As this is clearly an incomplete formula, Ranganathan postulated two further devices. His fundamental categories can apply at different Levels. These are (again broadly) what we would call subfacets, but can be used to specify basic facets such as Kinds, Parts and Properties. The other device is Rounds where the PME formula can begin a second round at some subordinate position in the citation order - typically to introduce Agents. Every class has its own facet formula, based on PMEST with different Levels and Rounds as required. This is difficult enough, and is not made easier by Ranganathan’s adherence to his Law of Parsimony - trained as a mathematician, he believed in giving information succinctly, to the point of desiccation. Neither is it made easier by CC’s notation, which is of a desperate complexity. It uses a range of non-alphanumeric characters as facet indicators in a manner comparable to UDC. However, whereas UDC otherwise confines itself to numbers, CC also has upper and lower case letters, as well as using a few letters as honorary numbers to extend the notational base.

While Ranganathan is undoubtedly the father of modern classification theory, and one of the fathers of the theory of controlled languages generally, his CC has few users in Western contexts. However, PMEST remains a very worthwhile mnemonic in a range of professional applications.

Modifying Published Classification Schemes

A published classification scheme is a complex package, and whatever scheme is in use for a particular application, there is a good chance that its managers will feel dissatisfied with some aspects, and contemplate modifying it. Reasons may include:

Providing extra specificity for applying a general classification to a special collection.

Giving a special collection a shorter base notation.

Altering the citation order, to bring together distributed relatives (e.g. in DDC in an academic library, to bring together all aspects of Geography, or to arrange literary works by Language - Period - Author instead of DDC’s preferred Language - Form - Period - Author).

To simplify the classification.

Modifications are of two kinds:

Making use of one or more of the scheme’s own published alternatives. For example, DDC has an option that permits literary works to be classified at -8 under each language irrespective of literary form.

Buying in or developing an unauthorized modification.

In either case, the implications must be carefully considered:

Many libraries use centrally produced bibliographic records that include DDC and/or LCC class numbers. Resources must be allocated to identify records whose class numbers require modifying, as well as to apply the local modification.

In the past, many modifications, certainly in British libraries, were made with the objective of providing extra detail to support subject indexing. This function is today done more effectively by other means.

If there is pressure from users to modify parts of the scheme, for example the better to reflect patterns of academic study, can the objective be met by other means, for example by guiding or user education?

Are the publishers of the scheme preparing an official revision? Local alterations to individual classes can be overtaken by a future edition of the classification.

Have identical or similar problems been encountered elsewhere? If so, how have they been addressed?

Some of these implications are managerial, others technical. Modifications to classification schemes were more commonly undertaken a generation or more ago, when published schemes and central bibliographic agencies were both less well developed than today, and when classification (at least in Britain) was expected to do more than arrange books on shelves and was propagated in some quarters almost as a panacea. Today, managers should satisfy themselves that their problem is real, unique, and incapable of resolution by other means before tampering with published schemes.

Special Classification Schemes

The general classification schemes that have been considered so far attempt to encompass all of knowledge. Special classification schemes are to be found in the Mowing environments:

bibliographies, indexing and abstracting services and their associated databases: for example INSPEC, Psyclnfo

shelf arrangements of special collections. These may be business, industrial and research libraries, specialist government libraries, organizations within the voluntary sector, or special collections within general libraries, especially local studies collections in public libraries. Special classifications for these purposes were often devised with indexing as an additional objective

shelf arrangement of a particular class within a general classification: for example, Elizabeth Moys’s (1982) Classification Scheme for Law Books, originally to stand in for LCC’s then unpublished class K Law

thesaurofacets: a thesaurus having its systematic display developed with notation and rules for pre-coordination, enabling it to be used as a shelf classification as well as for post-coordinate retrieval. The eponymous original was the English Electric Thesaurofacet of 1969

records management systems where files are stored in a topic-related order.

In general, schemes aim to cover just one subject area, or to meet the interests of one user group. More specifically, their types include:

schemes restricted to a conventional subject area or discipline: for example, music, insurance, chemistry

schemes devised for other associations of topics: for example, local collections, industrial libraries, archives

schemes for a certain type of user: for example, children, general browsers

schemes for documents in a particular physical form: for example, pictures, sound recordings; or restricted to a certain form of publication: for example, patents, trade catalogues

schemes for classifying the subject content of works of the imagination: for example, fiction, paintings. Conventional classification schemes classify these only by non-subject characteristics.

The rationale for applying a special classification scheme is essentially the same, writ large, as that for modifying a published classification, and the same caveats apply. The heyday of special classification schemes was in the 1960s and 1970s, when (as noted above) general classifications and central bibliographic agencies were relatively undeveloped, and classification was often expected to support an indexing function. Additionally, the great expansion of libraries at that time coincided with the flowering of post-war classification theory. For anyone setting up a special collection, a special classification tailored to its needs seemed the natural choice. Special classifications were made and published in great numbers, and their compilation by library school students was an exercise that was held to be both professionally relevant and academically rigorous, like learning Latin. Since the 1970s many such schemes have fallen by the wayside. Today library or database managers would be well advised to contemplate using an existing special classification only when satisfied that none of the major general classifications is viable, and to construct a special classification as an absolute last resort. The focus of activity has moved: in many cases it will be found that a thesaurus, locally maintained as an authority file, and perhaps based on a published thesaurus, will be all that is required for specific subject retrieval, and a published classification scheme will suffice for shelf arrangement.

Summary

The three major general classification schemes have all been in existence for upwards of 90 years. All have enjoyed some measure of official backing by government agencies, and this is undoubtedly of prime importance to their continuing success. The move over the past generation towards centrally produced records with classmarks centrally applied has led to a lower emphasis today on modifying published schemes. This, together with the virtual demise of the indexing function of classification, has reduced the need for special classification schemes.

References and Further Reading

Forest Press publish a range of materials for DDC, including a Dewey Audiocassette, Poster, Bookmark, and Cartoon Booklet Try the Dewey Rap, an 8y2-minute audiocassette that uses the solid beat and easy to remember rhyme of rap music to teach the DDC system. Or choose the cartoon Dewey poster for children and its companion bookmark. Also available is “I’ve Got Your Number”, a four-page comic-style Dewey booklet for grades K-5. All are teaching tools that are both educational and entertaining. Bookmarks available in English and Spanish.’ For information on these and other products, see the Dewey Web site at <http://www.oclc.org/ft)>.

Aitchison, J. (1986) A classification as a source for a thesaurus: the Bibliographic Classification of H. E. Bliss as a source of thesaurus terms and structure. Journal of Documentation, 42 (3), 160–181.

Batty, C. D. (1992) An Introduction to the Twentieth Edition of the Dewey Decimal Classification. London: Library Association.

Chan, L. M. (1990) The Library of Congress classification system in an online environment. Cataloging and Classification Quarterly, 11 (1), 7–25.

Chan, L. M. (1995) Classification, present and future. Cataloging and Classification Quarterly, 21 (2), 5–17.

Chan, L. M., Comaromi, J. P., Mitchell, J. S. and Satija, M. A. (1996) Dewey Decimal Classification: A Practical Guide, 2nd edn, revised for DDC21. Albany, NY: Forest Press.

Coates, E. J. (1960) British Catalogue of Music Classification. London: British National Bibliography.

Comaromi, J. P. (1990) Summation of classification as an enhancement of intellectual access to information in an online environment. Cataloging and Classification Quarterly, 11 (1), 99–102.

Dewey Decimal Classification and Relative Index (1996) 21st edition, 4 vols. Albany, NY: Forest Press. (The Introduction in Vol. 1 explains DDC’s basic principles and structure; and the Manual in Vol. 4 offers detailed advice on practical problems of implementation.)

Drabenstott, K. M. (1983) Searching and browsing the Dewey Decimal Classification in an online catalog. Cataloging and Classification Quarterly, 7, 37–68.

Foskett, A. C. (1996) The Subject Approach to Information, 5th edn. London: Library Association.

Marcella, R. and Newton, R. (1994) A New Manual of Classification. Aldershot: Gower.

Miksa, F. M. (1998) The DDC, the Universe of Knowledge and the Post-Modern Library New York: Forest Press.

Mills, J. and Broughton, V. (1977) Bliss Bibliographic Classification, 2nd edn, vol. titled Introduction and Auxiliary Schedules. London: Butterworths.

Moys, E. (1982) Moys Classification Scheme for Law Books, 2nd edn. London: Butterworths.

Satija, M. P. (1990) A critical introduction to the 7th edition (1987) of the Colon Classification. Cataloging and Classification Quarterly, 12 (2), 125–138.

Sweeney, R. (1983) Historical studies in documentation: the development of the Dewey Decimal Classification. Journal of Documentation, 39 (3), 192–205.

Thomas, A. R. (ed.) (1995) Classification: Options and Opportunities. New York: Haworth. (Also published as Cataloging and Classification Quarterly, 19 (3/4)).