Chapter 45

Spatial Cognition

As we move through the world, new visual, auditory, vestibular, and somatosensory inputs continuously impinge on the brain. Given such constantly changing input, it is remarkable how easily we are able to keep track of where things are. We can reach for an object, look at it, or kick it without making a conscious effort to assess its location. We understand the arrangement of parts in an object. We know automatically where we are in the environment and how to get from where we are to where we want to go. How is it that we can achieve the effortless mastery of space that underlies these abilities? This chapter outlines the contributions of brain areas in the parietal, frontal, and temporal lobes to the generation of actions in space, the understanding of spatial relations and navigation in the world.

Neural Systems for Spatial Cognition

Dorsal Stream Visual Areas Send Spatial Information to Parietal Cortex

Within the cerebral hemispheres, visual information is processed serially by a succession of areas beginning with the primary visual cortex of the occipital lobe. Within this hierarchical system, there are two parallel chains, or streams, of areas: the ventral stream, leading downward into the temporal lobe, and the dorsal stream, leading forward into the parietal lobe (Ungerleider & Mishkin, 1982) (see Chapter 44). Although the two streams are interconnected to some degree, it is a fair first approximation to describe them as separate parallel systems. Areas of the ventral stream play a critical role in the recognition of visual patterns, including faces, whereas areas within the dorsal stream contribute selectively to conscious spatial awareness and to the spatial guidance of actions, such as reaching and grasping. Dorsal stream areas have several distinctive functional characteristics, including containing a comparatively extensive representation of the peripheral visual field and being specialized for the detection and analysis of moving visual images. These traits would be expected in any system processing visual information for use in spatial awareness and in the visual guidance of behavior.

Although visual input is important for spatial operations, awareness of space is more than just a visual function. It is possible to apprehend the shape of an object and know where it is, regardless of whether it is seen or sensed through touch. Accordingly, spatial awareness, considered as a general phenomenon, depends not simply on visual areas of the dorsal stream but rather on the higher order cortical areas to which they send their output. The transition from areas serving purely visual functions to those mediating generalized spatial awareness is gradual, but has been accomplished by the time the dorsal stream reaches its termination in the association cortex of the parietal lobe.

Three Spatial Processing Streams Emanate from Parietal Cortex

Numerous association areas in the cerebral hemisphere mediate cognitive functions that depend in some way on the use of spatial information originating in parietal cortex. These areas occupy a continuous region of the cerebral hemisphere, encompassing large parts of the frontal, cingulate, temporal, parahippocampal, and insular cortices. They are connected to one another anatomically and to the parietal cortex by a parallel distributed pathway through which signals shuttle back and forth (Goldman-Rakic, 1988). Within this system, there at least three systems of areas with distinguishable functions (Kravitz, Saleem, Baker, & Mishkin, 2011) (Fig. 45.1). The premotor areas of the frontal lobe mediate the spatial guidance of motor behavior in the workspace around the body. The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex mediates spatial functions of higher order including spatial working memory. A system of areas spanning the cingulate gyrus, the medial temporal lobe, and the hippocampus mediates the ability to navigate in the environment and spatial episodic memory. The following sections describe the spatial functions of the parietal cortex and of the far-flung system of areas to which it projects.

Figure 45.1 Lateral view of the left cerebral hemisphere of a rhesus monkey. Pathways emanating from parietal cortex link it to other cortical regions with functions that depend on spatial information. Brain drawing, courtesy of Laboratory of Neuropsychology, NIMH.

Parietal Cortex

The Parietal Cortex Contributes to Spatial Perception and Attention

The parietal lobe is divided into superior and inferior parietal lobules. Within each lobule, several subdivisions are distinguished by anatomical and functional properties (Colby & Duhamel, 1991). In both humans and monkeys, the superior parietal lobule serves functions related primarily to somesthesis, or tactile perception, whereas the inferior parietal lobule serves functions related primarily to visuospatial cognition (Fig. 45.1). The intraparietal sulcus runs in between the superior and the inferior lobules. Within the sulcus there are several functionally distinct areas with independent representations of space. In monkeys, these include the medial intraparietal area (MIP), which is important for reaching behavior, the lateral intraparietal area (LIP), which is important for spatial attention, and the ventral intraparietal area (VIP), where visual and somatosensory representations of space are brought together. Functional imaging studies indicate that there are probably equivalent areas in humans although the detailed pattern of correspondence remains to be worked out (Grefkes & Fink, 2005).

Injury to the Human Parietal Cortex Causes Impairments of Spatial Function

The neurologist Balint in 1909 first described a group of behavioral impairments specifically associated with bilateral damage to the parietal lobe. Balint’s syndrome includes difficulty in executing eye movements to engage visual targets (ocular apraxia), an inability to perceive multiple objects at the same time (simultanagnosia), and inaccuracy in reaching for visual targets (optic ataxia). Many other impairments are now known to arise from damage to parietal cortex. These include constructional apraxia, an inability to copy, through drawing or physical manipulation, the spatial pattern in which things are arranged, and hemispatial neglect, a profound unawareness of the half of space opposite the injured hemipshere. The following sections describe in detail the symptoms of optic ataxia, constructional apraxia, and neglect.

Optic Ataxia: An Impairment of Visually Guided Reaching

After damage to the parietal cortex, some patients experience difficulty in making visually guided arm movements. This condition is referred to as misreaching, or optic ataxia (Perenin & Vighetto, 1988). Patients with optic ataxia experience difficulty in real-life situations requiring them to reach accurately under visual guidance. For example, a patient, when cooking with a frying pan, may see the handle perfectly well and yet be unable to reach accurately for it without looking directly at it (Rondot, de Recondo, & Dumas, 1977). Neuropsychologists have been able to characterize the reaching deficits of such patients in considerable detail by testing them in controlled situations.

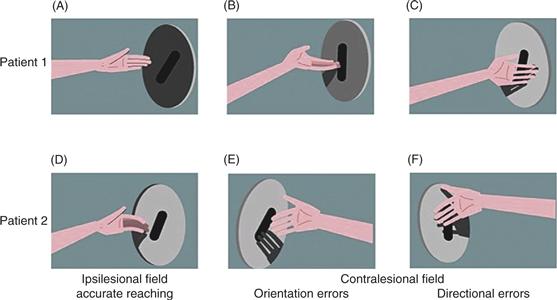

In the test illustrated in Figure 45.2, patients were required to reach out and insert one hand into a slot in the center of a disk held by the experimenter. The disk could be held in either the right or the left visual hemifield, while the patient looked straight ahead, and the patient could be asked to reach with either the right or the left hand. To perform the task, the patient had to direct the hand toward the center of the slot and orient the hand correctly so that it would pass into it. Pictures in the top row of Figure 45.2 show a patient with right parietal lobe damage reaching with the left hand. When the disk was positioned in the right (ipsilesional) visual field, the patient was able to reach accurately (Fig. 45.2A). And yet, when the disk was in the left (contralesional) visual field, the patient committed errors of hand orientation (Fig. 45.2B) and of reaching direction (Fig. 45.2C). The lower row of Figure 45.2 shows reaching by a patient with damage to the left parietal lobe. When using the left hand in the left (ipsilesional) visual field, this patient was also able to reach accurately (Fig. 45.2D). However, when using the right hand in the right (contralesional) visual field, the patient committed errors of hand orientation (Fig. 45.2E) and of reaching direction (Fig. 45.2F).

Figure 45.2 Optic ataxia. Patients can reach accurately (A and D) when using the ipsilesional hand in the ipsilesional visual field, but they make errors of hand orientation (B and E) and of direction (C and F) when reaching into the contralesional visual field. The top and bottom rows show the performance of two different patients.

These results demonstrate that optic ataxia may be lateralized, occurring only when the patient is required to point to targets in one visual hemifield or only when one hand is used for pointing. In cases where the deficit is restricted to a single hemifield or a single arm, the affected hemifield or arm is usually opposite the injured parietal lobe. This is expected because the parietal lobe of each hemisphere mediates communication between more posterior visual areas (which represent the contralateral half of visual space) and more anterior motor areas (which represent the contralateral arm). There are, however, cases in which the problem is bilateral or occurs for specific combinations of arm and hemifield. Optic ataxia is not simply a problem with visuospatial perception, as indicated by the fact that performance with one arm may be perfectly normal. Nor is it simply a motor problem, as indicated by the fact that patients unable to reach accurately for visual targets can commonly touch points on their own bodies accurately under proprioceptive guidance. Optic ataxia is best characterized as an inability to use visuospatial information to guide arm movements.

Constructional Apraxia: Inability to Reproduce the Spatial Relations of Parts

After injury to the parietal cortex, some patients experience difficulty in apprehending the spatial relations among elements in a scene. They cannot judge whether two objects are of the same size or which of two objects is closer. When asked to copy simple line drawings or to draw from memory, they omit or transpose parts. When attempting to reproduce with an arrangement of matchsticks a visible model in the shape of a four-pointed star, they make gross errors (Fig. 45.3). The problem does not lie in a loss of fine motor control, as evidenced by the local precision with which they can arrange the matchsticks in globally incorrect configurations. The problem might arise from an inability to organize complex actions in space under visual guidance. Indeed the traditional term “apraxia” implies flawed organization of voluntary actions. It appears, however, that the difficulties arise at the stage of spatial perception rather than at the subsequent stage of motor execution. For example, in one patient with parietal-lobe injury, “difficulties of writing in print were entirely derived from his inability to locate letters and numbers on the page under visual control. Writing cursive with lowercase letters was good, since this does not require specifically visual positioning of each letter” (Vaina, 1994). Constructional apraxia, by this interpretation, is a deficit of visuospatial cognition (which depends on processing where things are relative to each other) and thereby stands in contrast to optic ataxia, a deficit of visuomotor guidance (which depends on processing where things are relative to our own bodies).

Figure 45.3 Constructional apraxia. Patients with parietal lobe injury make gross errors when attempting to arrange matchsticks to resemble a visible model with the shape of a four-pointed star. Cases are labeled R or L to indicate that the site of injury was in the right or left hemisphere.

Hemispatial Neglect: Unawareness of the Contralesional Half of Space

Hemispatial neglect is a classic symptom of injury to the parietal cortex. Its key manifestation is a lateralized failure of spatial awareness. The most common form of neglect arises from damage to the right parietal lobe and is manifested as a failure to detect objects in the left half of space. Patients with neglect experience problems in daily life, such as colliding with obstacles on the contralesional side of the body or mistakenly identifying letters on the contralesional side of a written word. When asked to copy pictures or to draw simple objects from memory, they leave out details on the affected side. When asked to say whether two objects are the same or different, they tend to indicate that two dissimilar objects are the same if the differentiating details are on the contralesional side.

Neglect involves more than just a defect of attention to contralesional sensory events. For example, patients fail to report detail on the left half of an object even when they are asked to form a mental representation of the object by viewing it one part at a time as it passes slowly behind a vertical slit. In a famous set of experiments, patients were asked to imagine themselves in a familiar public setting and then to report what they would be able to see around them (Bisiach & Luzzatti, 1978). When they imagined standing at one end of the town square, patients described the buildings on the right side and failed to report buildings on the left. However, when instructed to imagine themselves standing at the other end of the square, facing in the opposite direction, they now failed to mention buildings on the left that they had described just moments before and were able to describe buildings on the right that they had previously omitted. These patients were unable to form a mental representation of the contralesional half of space even when the requirement to direct attention to sensory input on that side was altogether removed.

The fact that neglect affects the half of space opposite the injured hemisphere suggests that each parietal lobe must represent the opposite half of space. On the face of it, this proposition does not sound particularly surprising. Most visual areas in each hemisphere represent the opposite half of the visual field, most somatosensory areas represent the opposite half of the skin surface, and most motor areas represent muscles on the opposite half of the body. Injury to these areas leads to a sensory loss or motor impairment that affects the opposite half of a functional space defined with respect to some anatomical reference frame (the retina, the skin, or the muscles). In contrast, injury to the parietal cortex gives rise to a neglect that may be defined with respect to any of several spatial reference frames. These fall into two broad classes: egocentric reference frames, in which locations are represented relative to the observer, and allocentric reference frames, in which locations are represented in coordinates extrinsic to the observer. Examples of egocentric reference frames include those centered on the hand or the body. Allocentric reference frames include those centered on an environmental landmark or an object of interest. Patients with neglect often show deficits with respect to more than one reference frame. The following sections describe evidence for impairments relative to multiple spatial reference frames in neglect.

A patient with left hemispatial neglect, looking straight ahead at the center of some object, will tend not to see detail on its left side. This observation is open to several interpretations. The simplest interpretation is that stimuli presented in the left visual field tend not to be registered. However, the fundamental problem might actually be with registering stimuli that are to the left of the head, the torso or the object itself. These possibilities cannot be distinguished without disentangling the various reference frames. Experiments aimed at identifying the spatial reference frame in neglect indicate that a patient’s failure to detect a stimulus is affected not only by its location relative to the retina but also by its location relative to the object or array within which it is contained, by its location relative to the body, and even by its location relative to a gravitationally defined reference frame. Patients span a continuum from exhibiting predominantly egocentric to predominantly allocentric neglect.

In many patients, a component of neglect is object centered. If these patients are presented with an image anywhere in the visual field, they tend to ignore its left side. In one experiment, patients with left hemispatial neglect were required to maintain fixation on a small spot while chimeric faces (images formed by joining at the midline half-images representing the faces of two people) were presented at various visual field locations. Their reports of what they saw were based predominantly on the right halves of the chimeric images. This was true even when the entire composite face was presented within the right visual hemifield. In a second experiment, patients with left hemifield neglect were required to maintain fixation on a small spot while four stimuli in a horizontal row were presented. One of the stimuli was a letter that was to be named aloud. When the letter was at the leftmost location within the array, patients were slowest to name it, even when the entire array was in the right visual field.

A particularly dramatic way of demonstrating the object-centered nature of neglect is to ask patients to make copies of simple line drawings (Marshall & Halligan, 1993). When asked to copy a picture of two flowers, a patient with right parietal lobe damage saw and copied each flower but omitted the petals on the left half of each, thus showing evidence of left object-centered neglect (Fig. 45.4A). When the same two flowers were joined by a common stem, the patient saw and copied the plant, but omitted details on its left side, including all of the leftmost flower, thus showing neglect for the left half of the larger composite object (Fig. 45.4B).

Figure 45.4 Object-centered neglect. When asked to copy the two drawings on the left, a patient made the two copies on the right. Detail is omitted from the left half of each object rather than from the left half of the drawing as a whole.

Patients with parietal lobe damage sometimes exhibit neglect defined with respect to allocentric reference frames other than those centered on an object. The role of a gravitational reference frame in neglect has emerged from studies in which patients face a display screen either while sitting upright or while lying on their side (Ladavas, 1987). When the patient sits upright, the right and left halves of the screen coincide with the right and left retinal visual fields. However, when the patient lies on one side while facing the screen, the situation is changed. Reclining on the right side, the patient sees the right and left halves of the screen as being in the upper and lower visual fields, respectively. Applying this procedure to patients with left hemispatial neglect enables the investigator to pose the question: Is the neglect specific for the left retinal visual field or is it specific for the left half of the screen? Neglect turns out to depend in part on each of these factors.

Further evidence that the parietal cortex represents the locations of objects relative to an external framework comes from the observation that neglect, in some patients, is restricted to stimuli within a certain range of distances from the body. The form of neglect termed peripersonal or proximal is specific for stimuli in the immediate vicinity of the body. Another form of neglect, termed extrapersonal, is specific for more distant stimuli. The implication of these findings is that there is a localization of function within the parietal cortex and that neurons in discrete areas process sensory input from objects at different distances. Discrete areas of the parietal cortex are known to be specialized for relaying sensory information to different motor systems. Sensory input from peripersonal space is uniquely significant for guiding reaching movements. In contrast, sensory input from greater distances (extrapersonal space) is useful primarily for the control of eye movements.

Lesions of the Parietal Cortex in Monkeys Produce Spatial Impairments

The original distinction between dorsal and ventral processing streams in the primate visual system was based in part on differences in the effects of lesions of the parietal cortex, the terminus of the dorsal stream, and inferior temporal cortex, the terminus of the ventral stream (Ungerleider & Mishkin, 1982). Monkeys with parietal lesions exhibit a selective impairment of visuospatial cognition. For example, they cannot judge which of two identical objects is closer to a visual landmark. In contrast, lesions of inferior temporal cortex produce deficits in visual pattern recognition (see Chapter 44).

In addition to visuospatial cognitive deficits, monkeys with parietal lesions also exhibit deficits of visuomotor guidance. After parietal lesions, monkeys have difficulty directing eye movements toward targets in the hemispace opposite the side of the lesion (Lynch & McLaren, 1989). Further, when two targets are presented simultaneously in the ipsilesional and contralesional fields, monkeys with parietal lesions tend to ignore the contralesional stimulus, an effect termed visual extinction. Parietal lesions also interfere with the ability of a monkey to reach toward an object. Lesions confined to the inferior parietal cortex impair reaching with the contralesional limb toward a target in contralesional space. Lesions extending across the intraparietal sulcus to include the superior parietal cortex produce impairments in reaching with the contralesional arm into either half of space. In sum, monkeys with parietal lesions exhibit impairments both of visuospatial cognition and of visuomotor guidance.

Parietal Neurons Encode the Spatial Attributes of Objects and Actions

To understand more precisely how the parietal cortex contributes to spatial cognition, several groups of investigators have measured the electrical activity of single neurons during the performance of spatial tasks. These studies were carried out in alert monkeys trained to make movements to visual targets. Because brain tissue itself has no sensory receptors, microelectrodes can be introduced into the brain without disturbing the performance of an animal on a task. By recording neuronal activity during specially designed tasks, neural activity can be related directly to the sensory, cognitive, and motor processes that underlie spatial behavior. The following sections describe how neurons in specific areas within the parietal cortex are selectively activated during spatial tasks and how they contribute to spatial representation and cognition.

Area VIP: Head-Centered Visual and Somatosensory Responses

The ventral intraparietal area (area VIP) is a functionally and anatomically defined area that lies at the junction of the visual and somatosenory districts within parietal cortex. Individual neurons respond strongly to moving stimuli and are selective for both the speed and the direction of the stimulus (Colby, Duhamel, & Goldberg, 1993). In this respect, VIP neurons are similar to those in other dorsal stream visual areas that process stimulus motion, especially areas MT and MST (see Chapter 26). An important finding in area VIP is that most of these visually responsive neurons also respond to somatosensory stimuli (Duhamel, Colby, & Goldberg, 1991). These neurons are truly bimodal in the sense that they can be driven equally well by either a visual or a somatosensory stimulus. Most of these bimodal neurons have somatosensory receptive fields on the head or face that match the location of their visual receptive fields. This correspondence is illustrated in Figure 45.5, which shows visual and somatosensory receptive fields for several individual VIP neurons.

Figure 45.5 Matching visual and somatosensory receptive fields of neurons from area VIP. On each outline of the head of the monkey, the patch of color corresponds to the somatosensory receptive field of one neuron. On the square above the head, the patch of texture corresponds to the visual receptive field of the same neuron. The square can be thought of as a screen placed in front of the monkey so that its center was directly ahead of the monkey’s eyes at the time of visual testing.

From Duhamel et al. (1991) with permission of Oxford University Press.

Three kinds of correspondence are found in VIP neurons. First, for each neuron, receptive fields in each modality match in location. For example, a neuron that responds to a visual stimulus in the upper left visual field also responds when the left brow is touched, and a neuron with a foveal visual receptive field also responds to cutaneous stimulation around the mouth. Second, receptive fields match in size. For example, neurons with visual receptive fields around the fovea and somatosensory receptive fields around the mouth have especially small receptive fields in both modalities. This makes sense becase the fovea and the mouth are both regions of high spatial acuity. The third type of correspondence is in the preferred directions of movement. For example, a neuron responsive to a visual stimulus moving toward the right also responds when a small probe is brushed lightly across the face of the monkey moving to the right. In sum, visual and somatosensory receptive fields for individual VIP neurons match in location, size, and directional preference.

The correspondence in receptive field locations across modalities immediately raises a question: What happens to the relative locations of the visual and somatosensory receptive fields when the eyes move? If the visual receptive field were retinotopic, it would move when the eyes do; if the somatosensory receptive field were somatotopic, it would remain in place when the eyes move. Consequently, the correspondence in location between the visual and somatosensory receptive fields would be broken by eye movements.

The answer is that visual receptive fields are linked to the skin surface and not to the retina. A neuron that responds best to a visual stimulus approaching the forehead and has a matching somatosensory receptive field on the brow will continue to respond best to a visual stimulus moving toward the brow regardless of where the monkey is looking. Thus, both visual and somatosensory receptive fields are defined with respect to the skin surface. In this sense, the receptive fields are head centered: a given VIP neuron responds to stimulation of a certain portion of the skin surface and to the visual stimulus aligned with it no matter which part of the retina the image falls on.

In sum, neurons in area VIP encode bimodal sensory information in a head-centered representation of space. This kind of representation would be most useful for guiding head movements. Anatomical studies indicate that area VIP sends information to premotor cortex including the specific region that is involved in generating head movements.

Area LIP: Retina-Centered Attentional Signals

The lateral intraparietal area (area LIP) is a functionally defined area within the visual district of parietal cortex. Neurons in LIP exhibit several different kinds of activity during spatial tasks (Colby, Duhamel, & Goldberg, 1996). First, LIP neurons, like neurons in striate and extrastriate visual cortex (see Chapter 26), respond to the onset of a visual stimulus in the receptive field of the neuron. Second, these visual responses are enhanced when the monkey attends to the stimulus: the amplitude of the visual response is increased when the stimulus or stimulus location becomes the focus of attention. This enhancement occurs no matter what kind of movement the animal will use to respond to the stimulus. Regardless of whether the task requires a hand movement or an eye movement or requires that the monkey refrain from moving toward the stimulus, the visual response of an LIP neuron becomes stronger when the stimulus is made behaviorally relevant. This means that the same physical stimulus arriving at the retina can evoke very different responses in cortex as a result of spatial attention.

A third important feature of LIP neuron activity is the sustained responses observed when the monkey must remember the location at which the stimulus appeared. In this task, a stimulus is flashed only briefly, but the neuron continues to fire for several seconds after the stimulus is gone, as though it were holding a memory trace of the target location. A particularly intriguing question in understanding spatial representation concerns the fate of this memory-related activity in area LIP following an eye movement, as will be described later. A fourth kind of activation commonly observed in LIP neurons is related to performance of a saccade—a rapid eye movement—toward the receptive field. Some LIP neurons fire just before the monkey initiates a saccade that will move the fovea onto a target presented in the receptive field. LIP neurons have overlapping sensory and motor fields, just like neurons in the superior colliculus (see Chapter 32). Finally, LIP neuron activity can be modulated by the position of the eye in the orbit (Andersen, Bracewell, Barash, Gnadt, & Fogassi, 1990). For instance, the visual response of a given cell may become larger when the monkey is looking toward the left part of the screen than when it is looking toward the right. This property is of interest because it suggests that neurons in area LIP contribute to spatial representations that go beyond a simple replication of the retinal map.

In sum, individual LIP neurons have receptive fields at particular retinal locations; they carry visual-, memory-, and saccade-related signals; and their activity can be modulated by attention and eye position. Activity in area LIP cannot be characterized as a simple visual or motor signal. It is probably closer to the truth to think of the firing of an LIP neuron as reflecting how much attention is currently being directed to the location occupied by its receptive field.

Area LIP: Updating of Spatial Information during Eye Movements

Every time we move our eyes, each object in our surroundings activates a new set of retinal neurons. Despite this ever changing input, we experience a stable visual world. How is this possible? More than a century ago, Helmholtz proposed that the reason the world appears to stay still when we move our eyes is that the “effort of will” involved in making a saccade simultaneously adjusts our perception to take that specific eye movement into account. He suggested that when a motor command to move the eyes is issued, a copy of that command, or corollary discharge, is sent to brain areas responsible for generating our internal image of the world. This image is then updated so as to be aligned with the new visual information that will arrive in the cortex after the eye movement. A simple experiment shows that Helmholtz’s account must be essentially true. When the retina is displaced by pressing on the eye, the world does seem to move, presumably because there is no corollary discharge. Without that internal knowledge of the intended eye movement, there is no way to update the spatial representation of the world around us.

Neurons in area LIP contribute to this updating of the internal image (Duhamel, Colby, & Goldberg, 1992). The experiment illustrated in Figure 45.6 shows that the memory trace of a stimulus is updated when the eyes move. The activity of a single LIP neuron was recorded under three different conditions. In the first set of trials, the monkey looked at a fixed point on the screen while a stimulus was presented in the receptive field (Fig. 45.6A). In the diagram at the top of Figure 45.6A, the dot is the fixation point, the dashed circle shows the location of the receptive field, and the asterisk represents the visual stimulus. The time lines just below the diagram indicate that the vertical and horizontal eye positions remained steady throughout the trial, demonstrating that the monkey maintained fixation. The stimulus time line shows that the stimulus appeared 400 ms after the beginning of the trial and continued for the entire trial. The raster display below plots the electrical activity of a single LIP neuron in 16 successive trials. In these rasters, each small dot indicates the time at which an action potential occurred, and each horizontal line of dots represents activity in a single trial. In each trial there was a brief initial burst of action potentials shortly after the stimulus appeared, followed by continuing neural activity at a lower rate. The histogram at the bottom of Figure 45.6A shows the average firing rate as a function of time. The visual response in Figure 45.6A is typical of that observed in neurons in many visual areas: the neuron fired when a stimulus appeared in its receptive field.

Figure 45.6 Remapping of visual memory trace activity in area LIP. The activity of a single neuron was recorded under three different conditions. (A) Simple visual response to a constant stimulus in the receptive field, presented while the monkey is fixating. The rasters and histogram are aligned on the time of stimulus onset. (B) Response following a saccade that brings the receptive field onto the location of a constant visual stimulus. (C) Response following a saccade that brings the receptive field onto the location where a stimulus was presented previously. The stimulus is extinguished before the saccade begins so it is never physically present in the receptive field. The neuron responds to the updated memory trace of the stimulus. V, vertical eye position; H, horizontal eye position.

From Duhamel et al. (1992).

In the second set of trials (Fig. 45.6B), a visual response occurred when the monkey made an eye movement that brought a stimulus into the receptive field. At the beginning of the trial, the monkey looked at the fixation point on the left, and the rest of the screen was blank. Then, simultaneously, a new fixation point appeared on the right and a visual stimulus appeared above it. The monkey made a saccade from the old fixation point to the new one, indicated by the arrow. The eye movement was straight to the right so only the horizontal eye position trace shows a change. At the end of this saccade, the receptive field had been moved to the screen location containing the visual stimulus. The rasters and histogram in Figure 45.6B are aligned on the time that the saccade began. In each trial, the neuron began to respond after the receptive field had landed on the stimulus. This result is just what would be expected for neurons in any visual area with retinotopic receptive fields.

The novel finding is shown in Figure 45.6C. In this third set of trials, the monkey made a saccade that would bring a stimulus into the receptive field, just as in the second set of trials. The only difference was in the duration of the stimulus, which lasted for a mere 50 ms instead of staying on for the entire trial. As can be seen on the stimulus time line, the stimulus actually disappeared before the saccade began. This means that it was never physically present in the receptive field. Nevertheless, the neuron fired as though there were a stimulus in its receptive field. This result indicates that LIP neurons respond to the memory trace of a previous stimulus. Moreover, the representation of the memory trace is updated at the time of a saccade. The general idea of how a memory trace can be updated is as follows. At the beginning of the trial, while the monkey is looking at the initial fixation point, the onset of the stimulus activates neurons whose receptive fields encompass the stimulated location. Some of these neurons will have tonic activity and continue to respond after stimulus offset, encoding a memory of the location at which the stimulus occurred. When the monkey moves its eyes toward the new fixation point, a copy of the eye movement command is sent to parietal cortex. This corollary discharge causes the active LIP neurons to transmit their activity to a new set of neurons whose receptive fields will encompass the stimulated screen location after the saccade. By means of this transfer, LIP neurons encode the spatially updated memory trace of a previous stimulus.

The significance of this finding lies in what it illustrates about spatial representation in area LIP. It indicates that the internal image is dynamic rather than static. Tonic, memory-related activity in area LIP not only allows neurons to encode a salient location after the stimulus is gone but also allows for dynamic remapping of visual information in conjunction with eye movements. This updating of the internal visual image has specific consequences for spatial representation in the parietal cortex. Instead of spatial information being encoded in purely retinotopic coordinates, tied to the specific neurons initially activated by the stimulus, the information is encoded in eye-centered coordinates. This is a subtle distinction but a very important one in generating accurate spatial behavior. Visual information encoded in eye-centered coordinates tells the monkey not just where the stimulus was on the retina when it first appeared, but where it would be on the retina following an intervening eye movement. The result is that the monkey always has accurate information with which to program an eye movement toward a real or a remembered target. These phenomena probably occur in the human brain as well, as indicated by the observation that parietal injury can interfere with the ability to keep accurate track of a remembered location during a saccade.

In sum, neurons in area LIP encode the locations of present and remembered visual stimuli in an eye-centered reference frame. This observation suggests that area LIP is involved in eye movement control. It fits with the fact that LIP is strongly and directly connected to other brain centers involved in the control of eye movements, including the frontal eye field and superior colliculus (see Chapter 32).

Area LIP Is Downstream from Spatial Decision Processes

Spatially selective neuronal activity in area LIP is graded in strength. If the monkey’s attention to a given location or intention to make a saccade in a given direction increases in strength, then the firing of LIP neurons with response fields in that direction also increases. This has been demonstrated in decision tasks—tasks requiring the monkey to decide which of several possible saccades to make. A decision can be either sensory-based or value-based. In a sensory decision task, the monkey must judge whether a visual display contains dots moving to the right or left and must report the judgment by executing a rightward or leftward saccade (Roitman & Shadlen, 2002). If the motion stimulus is weak, requiring the monkey to integrate sensory information over time, the neuronal signal reflecting the decision develops slowly. If the motion stimulus is strong, allowing the monkey to make an instantaneous decision, the neuronal signal rises sharply. Thus, the evolution of the monkey’s decision is reflected in the activity of spatially selective LIP neurons. In a value-based decision task, the monkey chooses between a saccade to the right and a saccade to the left on the basis of prior experience indicating that one of the saccades is more likely than the other to yield a valued juice reward (Sugrue, Corrado, & Newsome, 2004). During the preparatory period of the trial, LIP neurons fire strongly if the target in their response field is associated with a valuable reward. In this task the activity of spatially selective LIP neurons reflects the value of the target. These two findings do not necessarily indicate that LIP plays a direct role in making sensory or value-based decisions. They can also be explained on the assumption that LIP neurons mediate attention or motor preparation and that they fire more strongly when attention or motor preparation is more intense (Maunsell, 2004).

Summary

The parietal cortex plays a critical role in spatial awareness. Injury to the parietal cortex in humans and monkeys leads to deficits of visuomotor guidance and visuospatial cognition. Parietal neurons in monkeys construct a representation of space by combining signals from multiple sensory and motor modalities. Neurons in different divisions of parietal cortex represent locations relative to several body-centered reference frames including ones centered on the eye and head. Signals carried by these neurons are useful for visuomotor guidance. Recent studies have suggested that parietal neurons also represent locations relative to object-centered reference frames in the service of visuospatial cognition (Box 45.1).

Box 45.1 Area 7a Neurons Carry Object-Centered Signals in a Constructional Task

Many neurons in the monkey parietal cortex represent the locations of visual stimuli relative to parts of the body such as the eye (in area LIP) or head (in area VIP). The body-centered spatial information that they carry is potentially useful for visual guidance of actions such as looking at and reaching for things. Visuospatial cognition, however, requires understanding of where things are relative to each other rather than to the body. It is an interesting question whether monkeys are capable of visuospatial cognition and if so what neural mechanisms underlie it (Caminiti et al., 2010). This issue was clarified by a recent study indicating that monkeys indeed can perform a constructional task requiring the use of object-centered spatial information and that parietal neurons carry object-centered spatial signals during performance of the task (Chafee, Crowe, Averbeck, & Georgopoulos, 2005; Chafee, Averbeck, & Crowe, 2007). On each trial, the monkeys looked at the center of a monitor while two figures appeared in succession. First a simple block figure appeared (model in Fig. 45.7A). Then another block figure formed by removing one block from the model appeared (incomplete copy in Fig. 45.7A). Given a choice of two new blocks (choice array in Fig. 45.7A), the monkeys had to decide which one needed to be slid in horizontally to transform the incomplete copy into a duplicate of the model. On recording from parietal Area 7a, the experimenters found that neurons fired while the monkeys were looking at the incomplete copy and that their firing encoded the location of the missing part. For example, the neuron of Figure 45.7 fired more strongly when the missing part was on the left (B, D, and F) than when it was on the right (C, E, and G). They signaled the location of the missing part relative to the object, not relative to the monkey. The fact that neurons in Area 7a carry object-centered spatial information is consonant with connectional anatomy. Area 7a differs from other parietal areas in being connected strongly to prefrontal cortex, which serves cognitive functions, rather than to premotor cortex, which mediates visuomotor guidance. The loss of neurons with object-centered spatial selectivity might underlie symptoms of parietal injury in humans, including constructional apraxia (Fig. 45.3) and object-centered neglect (Fig. 45.4).

Figure 45.7 Data from a neuron in parietal Area 7a with object-centered spatial selectivity. (A) While the monkey looked at a fixation point at the center of the screen (the central dot in each panel), a model block figure appeared followed, after a delay, by an incomplete copy from which one block had been removed. In this example, the block protruding halfway up the model on the left side was missing. A choice array consisting of two free blocks then appeared next to the incomplete copy. The monkey had to choose which free block to slide in horizontally so as to transform the incomplete copy into the original model (arrow). In this example, the lower block was the correct choice. (B–G) Data from an Area 7a neuron. This neuron fired during the period when the monkey was viewing the incomplete model. It fired much more strongly if the missing block was on the left of the model than if it was on the right. Note that the conditions consitute matched pairs in which monkey was viewing an identical incomplete copy (B–C, D–E, and F–G). The only thing that differed between the two conditions in a pair was the monkey’s awareness of the object-centered location (left or right) of the missing part.

From Chafee et al. (2005).

Frontal Cortex

Frontal Cortex Contributes to Voluntary Movement and the Control of Behavior

The frontal lobe is involved in spatial functions as a natural result of its being involved in behavioral control. The three main divisions of the frontal lobe are the primary motor cortex located on the precentral gyrus; the premotor cortex, located in front of the primary motor cortex; and the prefrontal cortex. The primary motor, premotor, and prefrontal areas all contribute to behavioral control, but they differ with respect to the quality of their contribution. This difference is seen in the effects of brain injury. Injury to the primary motor cortex leads to weakness and paralysis of the contralateral muscles. Injury to the premotor cortex leads to difficulty in producing movements under certain circumstances—for example, when the patient is asked to mime the use of a tool or to learn arbitrary associations between stimuli and responses. Finally, injury to the prefrontal cortex results in a syndrome characterized by reduced drive, reduced ability to form and carry out plans, and an impairment of working memory (see Chapter 50). These effects indicate that progressively more anterior parts of the frontal lobe contribute to progressively more abstract aspects of behavioral control. We describe following findings from the monkey that cast light on how space is represented in primary motor, premotor, and prefrontal cortex.

Neurons of Primary Motor Cortex Represent Movement Direction Relative to Both Intrinsic and Extrinsic Frames

The primary motor cortex contains a map of the muscles of the body in which the leg is represented medially, the head laterally, and other body parts at intermediate locations. Within this map are patches of neurons that represent different muscles. Neurons within a given patch receive proprioceptive input from a muscle or small group of synergistic muscles and send their output back to that muscle or group of synergists by way of a multisynaptic pathway through the brainstem and spinal cord. There have been many studies in which the electrical activity of neurons in the primary motor cortex is monitored while animals move (see Chapter 29). The general conclusion of these studies is that neurons in the primary motor cortex are active when the corresponding muscles are undergoing active contraction. Neurons in the primary motor cortex probably do more, however, than simply encode the levels of activation of individual muscles. One proposal is that they encode movement trajectories. Every voluntary movement can be described in two quite different but perfectly complementary ways: in terms of the lengths of the muscles or in terms of the position of the part of the body being moved. For example, during an arm movement, changes take place both in the lengths of muscles acting on the arm and in the position of the hand. Could it be that neurons in the primary motor cortex encode an extrinsic variable, such as the direction of movement of the hand, rather than an intrinsic variable such as which muscles are contracting?

Evidence for the idea that some neurons of the primary motor cortex encode movement direction relative to an extrinsic frame has come from studies in which monkeys make reaching movements in various directions. Individual neurons are selective for a specific direction of movement: a given neuron may fire most strongly during movements up and to the right and progressively less strongly for movements that deviate from the preferred direction (Schwartz, Kettner, & Georgopoulos, 1988). The patterns of selectivity are well defined, and the preferred directions of different neurons cover the range of possible movements fairly evenly. By recording the activity of the entire population of neurons one could, in principle, quite accurately describe the movement. The question remains whether these neurons are selective for the direction of movement in space or for the specific patterns of muscle activation associated with particular movements. In an elegant study, Kakei, Hoffman, and Strick (1999) recorded from neurons in the primary motor cortex while the monkey moved its hand in a single direction using different combinations of muscles. They discovered that the primary motor cortex contains both neurons selective for movement direction and neurons selective for patterns of muscle activation.

Premotor Neurons Resemble Parietal Neurons in their Patterns of Spatial Selectivity

One of the general functions of premotor cortex is to act as a conduit through which signals generated in parietal cortex control motor output. Connections between parietal and premotor cortex are organized topographically with the result that each functionally distinct subregion of parietal cortex projects particularly strongly to a related region in premotor cortex (Rizzolatti & Lupino, 2001). Premotor neurons are thought to have a more direct involvement in voluntary motor control than parietal neurons. However, they appear to preserve parietal codes for representing the locations of targets and the directions of movements. Thus, the functional properties of neurons in each region of premotor cortex mirror the functional properties of neurons in the related parietal region. For example, neurons in the division of ventral premotor cortex (PMv) linked to parietal area VIP respond both to visual and to somatosensory stimuli and possess head-centered receptive fields (Fogassi et al., 1992). Likewise, neurons in the frontal eye field (FEF), which is linked to Area LIP, possess retina-centered visual receptive fields and exhibit remapping in conjunction with eye movements (Umeno & Goldberg, 1997).

Neurons in the Supplementary Eye Field Encode the Object-Centered Direction of Eye Movements

A particularly interesting form of allocentric spatial representation analogous to that observed in area 7a (Box 45.1) has been observed in the supplementary eye field (SEF). The SEF is a division of the premotor cortex with attentional and oculomotor functions. Neurons in this area fire before and during the execution of saccadic eye movements. Several characteristics of the SEF set it apart from subcortical oculomotor centers and suggest that its contribution to eye movement control occurs at a comparatively abstract level. For example, neurons here fire while the monkey is waiting to make an eye movement in the preferred direction, as well as during the eye movement itself. Moreover, some SEF neurons become especially active when the monkey is learning to associate arbitrary visual cues with particular directions of eye movements.

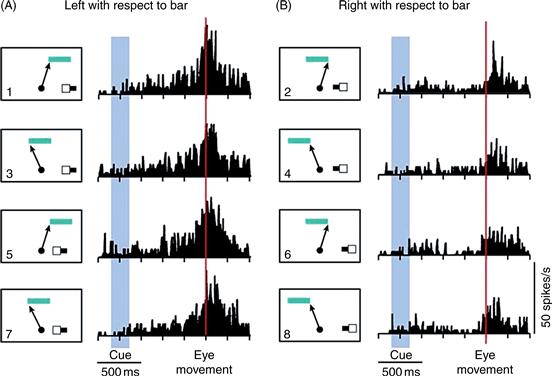

In monkeys trained to make eye movements to particular locations on an object, SEF neurons encode the direction of the impending eye movement as defined relative to an object-centered reference frame (Olson & Gettner, 1995). Regardless of where an object appears relative to the body, these neurons respond when the animal is planning to make an eye movement to a specific location on that object. An experiment demonstrating this point is shown in Figure 45.8. This figure shows the activity of a single SEF neuron while the monkey performed an eye movement task. At the beginning of each trial, the monkey fixated a dot at the center of a screen. While the monkey fixated, a sample and cue were presented in the right visual field. The cue flashed on either the right or the left end of the short horizontal sample bar. Following extinction of the sample–cue display, the monkey maintained fixation for a brief time. Then, simultaneously, the central spot was extinguished and a target bar appeared at an unpredictable location in the upper visual field of the monkey. The monkey had to make an eye movement to the end of the target bar corresponding to the cued end of the sample bar. Across the set of eight conditions, the object-centered direction of the eye movement was completely independent of its physical direction.

Figure 45.8 Data from a neuron in the SEF selective for the object-centered direction of eye movements. The monkey was trained to make eye movements to the right or left end of a horizontal bar. A cue appeared on the small sample bar shown in the lower right of each panel (1–8) to tell the monkey which end of the target bar (top in each panel) was relevant on a given trial. The arrow in the panel next to each histogram indicates the direction of the eye movement. The neuron fired strongly when the eye movement was directed to the left end of the target bar (left column) regardless of whether the physical movement of the eye was up and to the right (panels 1 and 5) or up and to the left (panels 3 and 7).

From Olson and Gettner (1995).

This situation made it possible to ask whether the activity of the neuron was related to the object-centered direction of the movement or to its physical direction. To the right of each panel in Figure 45.8 is shown the average firing rate of a single neuron as a function of time during the trial. Regardless of the direction of the physical movement of the eye, firing was clearly stronger on trials in which the monkey made an eye movement to the left end of the target bar than on trials in which the target was the right end of the bar. For example, in panels 1 and 2, the physical direction of the eye movement was exactly the same, and yet firing was much stronger when the left end of the bar was the target (panel 1) than when the right end of the bar was the target (panel 2). This neuron exhibited object-centered direction selectivity in the sense that it fired most strongly before and during movements to a certain location on an object.

Object-centered direction selectivity serves an important function in natural settings. In scanning the environment, we sometimes look toward locations where things are expected to appear, but which, at the time, contain no detail, for example, the center of a blank screen or the center of an empty doorway. Our eyes are guided to these featureless locations by surrounding features that define them indirectly. It is specifically in these cases that the SEF may contribute to the selection of the target for an eye movement.

The Prefrontal Cortex Mediates Working Memory for Spatial Information

Working memory is required to hold a plan in mind and carry it out step by step (see Chapter 50). The fact that this ability is severely impaired in some patients following prefrontal injury indicates that prefrontal cortex plays a crucial role in working memory. Insofar as plans and working memory have a spatial component, operations carried out by the prefrontal cortex are also spatial in nature. Single neuron-recording experiments in monkeys performing delayed-response tasks have demonstrated the importance of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex for both spatial and nonspatial forms of working memory (Funahashi, Bruce, & Goldman-Rakic, 1991). A delayed-response task consists of several trials, each several seconds long. At the beginning of each trial, a cue is presented briefly, instructing the monkey which response to make, but the reponse must be withheld until the end of the trial. Delayed-response tasks can be designed so that both the cues (for example, spots flashed to the right or left of fixation) and the responses (for example, eye movements to the right or left) are spatial. In the context of these spatial tasks, prefrontal neurons are active during the period between the cue and the signal to respond, when the monkey is holding spatial information in working memory. The simple interpretation of this pattern of activity is that it is a neural correlate of the monkey actively remembering the cue and holding in mind the intended response. This interpretation is consistent with results from brain imaging studies demonstrating prefrontal activation in humans performing working memory tasks.

The idea that the prefrontal cortex mediates spatial working memory has received further support from lesion experiments in monkeys. After injury to or inactivation of specific locations in the prefrontal cortex, monkeys are impaired at remembering locations in the opposite half of space. Their delayed responses are spatially inaccurate and the inaccuracy is exacerbated by making delays longer. An experiment demonstrating the importance of the prefrontal cortex for spatial working memory is illustrated in Figure 45.9, which shows behavioral data from a monkey trained to perform an oculomotor delayed-response task (Sawaguchi & Goldman-Rakic, 1994). At the beginning of each trial, the monkey fixated a spot at the center of the screen. While the monkey maintained fixation, a cue was flashed at one of six possible locations. Following presentation of the cue, a delay of 1.5 to 6 seconds ensued before the monkey was permitted to make an eye movement to the cued location. Data from a normal monkey are shown in the left column of Figure 45.9. In each panel, the six bundles of radiating rays represent the eye trajectories on trials when the cue was at the six different locations. Even when required to remember the cue for 6 seconds, the monkey made accurate eye movements. Data in the right column are from the same monkey after a dopamine antagonist was injected into the left prefrontal cortex. The ability of the monkey to remember the location of the cue remained intact when the cue was in the left (ipsilesional) visual field, as shown by the accurate eye movements. However, performance deteriorated on trials when the cue was in the right (contralesional) visual field. Especially after long delays (top panel), the direction of the eye movement began to deviate from the location of the cue, as if the working memory of the monkey were fading. The fact that this deficit was specific to long delays is noteworthy because it rules out any simple explanation based on interference with visual or motor processes as opposed to working memory itself.

Figure 45.9 Inactivation of the left prefrontal cortex disrupts spatial working memory in the right half of space. A monkey was trained to fixate a central spot while a peripheral cue was presented briefly at one of six locations. After an interval of 6, 3, or 1.5 seconds, the fixation spot was extinguished and the monkey made an eye movement to the remembered location. Each set of diverging rays shows the trajectories of eye movements executed under a certain set of conditions. The left column shows eye movement performance before inactivation by a dopamine antagonist. The right column shows performance after inactivation. When the cue was in the right hemifield and the monkey was required to remember its location over long delays, the movements became highly inaccurate.

Neural signals related to working memory are observed in object memory tasks as well as spatial tasks (see Chapter 50). In a task in which the monkey had to remember the identity of an object as well as its location, some neurons were selectively activated by remembering the identity of the object independently of its location (Rao, Rainer, & Miller, 1997). Thus, the functions of prefrontal cortex include but are not limited to spatial cognition.

Value Representation and Motivational Modulation in Frontal Cortex

In many areas of the frontal lobe, neurons fire more strongly when a monkey anticipates receiving a larger reward for making a saccade (Roesch & Olson, 2003). The firing of these neurons could signify either of two things. First, it might represent, in an economically meaningful sense, the value of the reward that the monkey expects to receive. The monkey might commit more or less firmly to making the saccade on the basis of how strongly the neurons are firing. Second, it might simply be related to motor planning, attention, or arousal—internal states enhanced when the monkey is more motivated. That these interpretations are different can be illustrated by a simple example. The neck muscles of some monkeys grow more tense when they are planning a saccade in expectation of getting a larger reward (Roesch & Olson, 2004). The tension of the neck muscles obviously reflects motivation and does not represent value in an economically meaningful sense. Whether the activity of frontal neurons represents value or reflects motivation cannot be determined by experiments manipulating solely the size of the expected reward because, as value increases, so does motivation.

This issue has been resolved by manipulating independently the size of the reward promised in the event of the monkey’s successfully completing the trial (one or three drops of juice) and the size of the penalty threatened in the event of failure (a one-second or eight-second time-out). A large promised reward and a large threatened penalty have opposite value but both act to increase motivation. Spatially selective neurons in premotor cortex fire more strongly when either a large reward has been promised or a large penalty has been threatened (Fig. 45.10). In other words, activity in these neurons is modulated by the animal’s level of motivation. In contrast, neurons in orbitofrontal cortex fire most strongly when a large reward has been promised and least strongly when a large penalty has been threatened. In other words, they represent anticipated value. The orbitofrontal cortex is a part of the limbic system known to be involved in emotional processes. Presumably, when the monkey considers an action that would lead to an outcome, neurons in orbitofrontal cortex signal the emotion that would be elicited by the outcome, thus representing its value. Value representations in orbitofrontal cortex may give rise to motivational modulation in premotor cortex.

Figure 45.10 Evidence that orbitofrontal neurons encode expected value whereas premotor neurons are subject to motivational modulation. A cue presented early in each trial instructed the monkey whether to make a rightward or leftward saccade at the trial’s end. It also indicated whether making the instructed saccade would lead to a large or small reward (three drops or one drop of juice). Finally, it indicated whether failure to make the saccade would lead to a large or small penalty (a 1-second or 8-second time-out). After a delay of several seconds, the monkey was permitted to respond. For a saccade in the instructed direction, the monkey received the promised reward. For any other response, the monkey incurred the threatened penalty. The orbitofrontal neuron encoded the value of the outcomes predicted by the cue. It responded most strongly when the combined predicted outcome was best (A: large reward promised and small penalty threatened), at an intermediate level when it was middling (B: small reward promised and small penalty threatened) and least strongly when it was worst (C: small reward promised and large penalty threatened). The premotor neuron fired during the delay period at a rate that reflected how motivated the monkey was. It fired most strongly when the monkey had something significant to work for, either earning a large reward (D) or avoiding a large penalty (F) and least strongly when little was at stake (E). In each panel, time is on the horizontal axis. The histogram represents the average firing rate of the neuron as a function of time during the trial. In the underlying raster display, each horizontal line corresponds to a single trial and each dot represents an action potential.

From Roesch and Olson (2004).

Summary

Neurons in the frontal cortex represent spatial information in conjunction with the role they play in controlling spatially organized behavior. Neurons in the primary motor cortex encode the directions of movements. Neurons in the premotor cortex encode locations relative to numerous body-centered reference frames. SEF neurons encode locations in an allocentric, object-centered representation. Neurons in the prefrontal cortex encode the locations of and identity of objects being held in short-term memory. The motor and cognitive spatial signals carried by neurons in the frontal cortex are subject to motivational modulation.

Medial Temporal Lobe

The Hippocampal System Mediates Declarative Spatial Memory

The hippocampus is an area of primitive cortex, or allocortex, hidden within the medial temporal lobe. It is connected to a set of immediately adjacent temporal-lobe areas, including the perirhinal, entorhinal, and parahippocampal cortices (Zola-Morgan & Squire, 1993). The hippocampal system plays a critical role in the formation of declarative memories in humans (see Chapter 48). Consequently, patients with damage to the hippocampal system sometimes exhibit quite dramatic impairments of spatial memory as manifest in navigational behavior. The noted patient H.M., for example, experienced profound difficulty in learning to navigate through a new neighborhood. Likewise, patient E.P., profoundly amnesic after extensive medial temporal damage resulting from a viral encephalitis, could not learn the layout of a new neighborhood (Teng & Squire, 1999). The deficit in these cases concerned the formation of declarative memories in general rather than some specifically spatial function. Navigation, in itself, was intact, as evidenced by good performance in neighborhoods familiar from before the injury. Moreover, the amnesia extended to non-spatial material, as evidenced by behavior such as failing to recognize examiners to whom the patients had been introduced only minutes before.

Parahippocampal and Retrosplenial Cortex Contribute to Navigation

The retrosplenial and parahippocampal areas are located in the medial temporal lobe close to the hippocampus. They are linked by multisynaptic pathways both to parietal cortex and to the hippocampus. Thus, they are strategically positioned to mediate navigational ability, which depends on both spatial information processing and memory. Studies in humans, based on functional imaging and on the analysis of the behavioral effects of lesions, indicate that these areas may indeed play a special role in environmental navigation (Epstein, 2008). The parahippocampal place area (PPA) and the retrosplenial cortex (RSC) respond with stronger functional activation to images of scenes than to images of faces or objects (see Chapter 44). Moreover, damage to the region of the medial temporal lobe within which they reside leads to topographic disorientation (Barash, 1998). In one form of topographic disorientation, thought to arise from damage to the PPA, individuals become lost because they cannot recognize places that should be familiar (Epstein, 2008). In another form of the disorder, thought to arise from damage to the RSC, individuals are able to recognize familiar places but are unable to orient from the familiar place to a distant destination (Epstein, 2008).

Neurons in the Rat Hippocampal System Encode Place and Heading

Recordings from hippocampal neurons in rats running mazes or exploring open areas have revealed a remarkable degree of spatial selectivity. Many neurons in the hippocampus have place fields: a given neuron will fire most strongly when the rat is within a certain sector of the environment. Different neurons have distinct place fields so that, collectively, they cover the environment (Fig. 45.11B). Place fields are defined relative to prominent environmental landmarks. When a radially symmetric eight-arm maze is rotated relative to a surrounding room containing salient landmarks the place fields remain fixed with respect to the room. Even in darkness, neurons continue to fire when the rat is in their place field, indicating that these responses are not simply visual. If the rat is placed in a new environment, hippocampal neurons develop new place fields rapidly. The location of the place field of a neuron in the new environment is generally unrelated to its location in the old environment. Thus, the hippocampus develops an entirely new place-field map for each new environment. This is true even in cases where the workspace is changed without any change in the surrounding room—for example, through replacement of an eight-arm radial maze by an open field.

Figure 45.11 Neurons in the hippocampal system fire differentially as a function of a rat’s location in the environment. (A) In this experiment, the rat moved freely through a square enclosure with low walls in which a card placed on one wall formed a visible landmark. (B) Data from six hippocampal neurons (H1 through H6) with place fields. Each heat map depicts the rate of firing of the neuron as a function of the rat’s location in the enclosure (red indicates strong activity and dark blue indicates weak activity). The top row and the bottom row, representing data from separate sessions, are included to indicate the reproducibility of environmental spatial selectivity. (C) Data from two entorhinal grid cells (E1 and E2). Conventions as in (B). Note that each grid cell has multiple sub-fields within the enclosure.

Neurons in other regions of the hippocampal system are sensitive to the direction in which the head is pointing. Sensitivity to heading is common in the postsubiculum, a cortical area adjacent to and closely linked to the hippocampus. Each postsubicular neuron fires most strongly when the head of the rat is pointing in its preferred direction and fires progressively less strongly as the orientation of the head of the rat deviates farther from that direction. In a room that is suddenly darkened, postsubicular neurons remain sensitive to the heading of the rat so long as the rat retains a sense of spatial orientation. When the sense of spatial orientation drifts away from veridicality during prolonged darkness, as evidenced by the occurrence of systematic errors on spatial tests, then the preferred headings of postsubicular neurons exhibit a commensurate drift. These observations establish that neurons of the hippocampal system are sensitive to the rat’s perceived heading.

Within limits, rats are able to maintain an accurate sense of place while they move through a dark environment. We know that they can do so both because they are able to find familiar locations and because the firing of their place cells is appropriately updated as they move. The updating of place cell activity depends on an underlying computation often termed path integration. In path integration, the rat’s old location and the rat’s own movement are added together to give the rat’s new location. The computation is easy to describe but the neural machinery mediating it has not been understood. Recent evidence from single-neuron recording studies of the entorhinal cortex has suggested a solution to this problem. The entorhinal cortex, a source of strong and direct input to the hippocampus, contains grid cells (Hafting, Fyhn, Molden, Moser, & Moser, 2005; Moser, Kropff, & Moser, 2008). In contrast to a hippocampal place cell, which possesses a single place field in any given environment, an entorhinal grid cell possesses a multitude of firing fields covering the environment in a strikingly regular hexagonal grid (Fig. 45.11C). The firing fields of different grid cells cover the environment at a variety of scales and phases so that for each location in the environment there is a unique pattern of activity across the population of grid cells. Thus, grid cells in the entorhinal cortex encode information about the rat’s current location and could relay this information to place cells in the hippocampus. The question remains: why should place information be represented in such a complex code at the level of entorhinal cortex? Soon after the discovery of grid cells, computational neuroscientists realized that representing environmental locations in a grid code could facilitate the computations that underlie path integration. Path integration has now been implemented in several models of the hippocampal system that incorporate grid cells (Fuhs & Touretzky, 2006; McNaughton, Bataglia, Jensen, Moser, & Moser, 2006).

Summary

The hippocampal system mediates the formation of declarative memories, including memories with spatial content. Injury to the hippocampal system induces a profound anterograde amnesia manifest in the spatial domain as an amnesia for neighborhood layout. In addition to mediating domain-general memory processes, the medial temporal lobe may make specific contributions to navigation in the environment. In humans, the parahippocampal and retrosplenial cortices contribute to recognizing familiar places and orienting from them to distant goals. In the rat hippocampal system, the existence of place cells, head-direction cells, and grid cells argues for a specific and dedicated role in maintaining and updating a representation of the animal’s location and heading in the environment.

Spatial Cognition and Spatial Action

The preceding sections described how spatial information is processed in cortical areas that serve distinct functions, such as motor control, attention, working memory, declarative memory, and navigation. Even within the motor system, there appears to be a fractionation of spatial functions in that neurons controlling movements of the eyes, head, and arm represent the locations of visible targets relative to eye-, head-, and hand-centered reference frames, respectively. In addition to these distinctions, there may be another fundamental distinction within brain systems mediating spatial functions. Areas mediating conscious awareness of spatial information may be partially separate from those mediating the spatial guidance of motor behavior. These functions might seem inseparable insofar as one must be aware of the location of a thing in order to look at it or reach for it. However, this is not necessarily the case. An indication that spatial awareness and spatially programmed behavior are distinguishable has come from studies of patients with “blindsight” (Weiskrantz, 1996). This condition arises as a result of injury to the primary visual cortex. Patients experience a scotoma, an area of blindness, in the part of the visual field represented by the injured cortex. The blindness is total in the sense that patients do not report seeing visual stimuli when stimuli are presented within the confines of the scotoma. Nevertheless, if patients are asked to look toward or to reach for an unseen stimulus, choosing the target by guesswork, their responses are directed to the correct location.

Similar findings have been reported in patients with diffuse pathology affecting widespread areas, including the prestriate visual cortex. One such patient, D.F., has been extensively studied in spatial tasks (Goodale et al., 1994). The results reveal an important distinction between spatial performance and spatial cognition. When asked to express spatial judgments (for example, to indicate the size of a visible object by spreading the thumb and forefinger), D.F. performs poorly. Nevertheless, when asked to make visually guided movements (for example, to reach for an object), she accurately adjusts her grip size and hand orientation under visual control to grasp the object efficiently. The fact that intact visuomotor performance coexists with profoundly impaired visuospatial perception in some patients seems to argue for the existence of distinct brain systems specialized for conscious spatial awareness and motor guidance. Many lines of evidence indicate that conscious spatial awareness depends on relatively lateral regions of parietal cortex while motor guidance depends on more medial regions of parietal cortex. Conscious spatial vision is distinct from conscious visual recognition, which depends on occipitotemporal cortex (see Chapter 44).

Summary

Spatial cognition is a function of many brain areas. No one area is uniquely responsible for the ability to carry out spatial tasks. Nevertheless, some generalizations can be made about the part of the problem that is solved in each brain region. The parietal lobe plays a crucial role in many aspects of spatial awareness. It contains numerous areas within each of which neurons carry spatial information relevant to a particular form of behavior.

Neural pathways emanating from parietal cortex relay spatial information to at least three cortical systems that elaborate it for specific purposes. The pathway to premotor cortex is critical for spatial guidance of actions in the workspace surrounding the body. The pathway to prefrontal cortex is critical for cognitive functions including spatial working memory. The pathway to the medial temporal lobe is critical for spatial declarative memory and for navigational ability.

Beneath the seeming unity of spatial experience lies a diversity of specific neural representations. The brain constructs not one but many internal representations of space. A challenge for the future is to understand how these many representations are bound up into that single seamless awareness of space with which each of us is familiar.

References

1. Andersen RA, Bracewell RM, Barash S, Gnadt JW, Fogassi L. Eye position effects on visual, memory, and saccade-related activity in areas LIP and 7a of macaque. Journal of Neuroscience. 1990;10:1176–1196.

2. Barash J. A historical review of topographical disorientation and its neuroanatomical correlates. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 1998;20:807–827.

3. Bisiach E, Luzzatti C. Unilateral neglect of representational space. Cortex. 1978;14:129–133.

4. Caminiti R, Chafee MV, Bataglia-Mayer A, Averbeck BB, Crowe DA, Georgopoulos AP. Understanding the parietal lobe syndrome from a neuropychological and evolutionary perspective. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;31:2320–2340.

5. Chafee MV, Averbeck BB, Crowe DA. Representing spatial relationships in posterior parietal cortex: Single neurons code object-referenced position. Cerebral Cortex. 2007;17:2914–2932.

6. Chafee MV, Crowe DA, Averbeck BB, Georgopoulos AP. Neural correlates of spatial judgment during construction in parietal cortex. Cerebral Cortex. 2005;15:1393–1413.

7. Colby CL, Duhamel J-R. Heterogeneity of extra-striate visual areas and multiple parietal areas in the macaque monkey. Neuropsychologia. 1991;29:517–537.

8. Colby CL, Duhamel J-R, Goldberg ME. Ventral intraparietal area of the macaque: Anatomic location and visual response properties. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1993;69:902–914.