SYMMETRY RETURNS TO THE OPERATIONAL LEVEL OF WAR

CHRONOLOGY

| Fall 1806 | Spain schemed against France to join her enemies. |

| Oct 25 | French troops under Marshal Davout entered Berlin. |

| Nov 21 | Napoleon issued his Berlin Decree initiating Continental System of Economic Warfare against Great Britain. |

| July 7, 1807 | Treaty of Tilsit between French and Russian Empires brought general peace to continental Europe |

| Oct 18 | General Jean Junot’s army entered Spain in order to invade Portugal Napoleon deposed the Spanish king and his son at Bayonne and appointed his brother. |

| Joseph Bonaparte became king | |

| Nov 30 | General Junot occupied Lisbon after Portuguese royal family fled. |

| May 2, 1808 | Spanish in Madrid revolted. Murat bloodily repressed the revolt, which spread to the rest of the country three weeks later. |

| July 20 | General Dupont surrendered to Spanish at Baylen. |

| August 1–21 | Sir Arthur Wellesley landed in Portugal and defeated Junot at Vimeiro. |

| September 25 | Sir John Moore took command of British army after Wellesley was recalled to Britain. |

| Fall 1808 | Napoleon scattered Spanish forces and recaptured Madrid. |

| Jan 17, 1809 | Napoleon left Spain and turned over pursuit of Moore to Marshal Soult. |

| Jan 16 | Battle of Corunna; British army escaped intact from Spain. |

| April 1809 | Austria declared war on France, Russia remained neutral. |

| April 19–22 | Battle of Eckmühl |

| April 22 | Wellesley arrived in Lisbon. |

| May 12 | Napoleon captured Vienna. |

| Wellesley defeated Marshal Soult at Oporto. | |

| May 20–21 | Archduke Charles defeated Napoleon at Aspern-Essling. |

| July 5–6 | Napoleon defeated Austrians at Wagram. |

| July 25–26 | Wellesley defeated Marshal Victor at Talavera. |

| October 14 | Austria signed Treaty of Pressburg with France |

The period after the Treaty of Tilsit (July 1807) encompassed the decline of Napoleon’s Empire and his generalship—although it is often portrayed as the apogee of his Empire. It also saw the resurgence of his enemies, the empires of Austria and Great Britain (with help from the Spanish and Portuguese), who began to win tactical and occasional operational victories against him on land, and, more often than not, against his marshals. French asymmetry of arms faded as their opponents adopted the Napoleonic model of the nation-in-arms, organized along the lines of the Grande Armée, and mimicked French tactics and combined arms to counter the threat posed by the Napoleonic system. The period also witnessed the defense becoming more powerful as Napoleon’s armies got bogged down fighting insurgencies in Spain, Portugal, and Southern Italy (Calabria). The French quagmire deepened when the British committed the bulk of their small army to fight in the Iberian Peninsula, using sea power for operational logistics and as an element of operational maneuver. At the same time, Austria took advantage of Napoleon’s involvement in Spain to return to the contest of arms in 1809. Military historian Robert Epstein has identified this period as encompassing “the emergence of modern warfare,” basing his argument on the symmetry of the 1809 campaign on the Danube between the armies of the French and Austrian empires.1

However, the outbreak of an extended insurgency in Spain, characterized by both regular and irregular, or guerilla, warfare, also resulted in a situation where the fundamental advantages of Napoleon’s army were checked by a particularly powerful form of insurgent war that historian Tom Huber has labeled fortified compound warfare.2 As manifested in Spain, this form of war saw the mixture of conventional operations by Spanish and Anglo-Portuguese armies with widespread guerilla operations over the vast, mountainous regions of Spain and Portugal. This presented their opponents with a dilemma; Napoleon’s troops could either concentrate to face their enemies’ armies or disperse to control the countryside, but not both. These nations were very poorly developed in infrastructure and with little arable land and armies starved marching about the arid plains and mountains in their attempts to conduct both regular and counterinsurgent operations. The Napoleonic logistical system, not always efficient even in the more developed areas of western and central Europe, broke down in Spain to a much greater degree. Command, control, and communications proved a nightmare due to the guerilla bands. Although French adversaries in Spain operated under similar constraints, they had absolute control of the waters surrounding the Iberian Peninsula courtesy of the Royal Navy and fought on and for their own soil. Also, the British established key fortified lodgments that they supplied by sea at places such as Lisbon, Gibraltar, and Cadiz from whence they sallied with military force and provided havens for guerillas and regulars alike. The French could not guard the entirety of the Iberian coast, let alone the coasts elsewhere in the Empire. They could pacify the interior of Spain to some degree, but the littoral areas were readily accessible to British ships, which provided supplies and food to forces operating throughout the Iberian Peninsula.3 With the outbreak of war with Austria in 1809, Napoleon found himself in a two-front war, with nearly 200,000 troops committed in Spain, many of them veterans commanded by his best marshals like Soult, Ney, Victor, and even the old revolutionary marshals Jourdan and Moncey.

Another way of viewing this chapter’s themes is to realize that as Jominian offensive operations become ever more indecisive (especially in Spain), the power of the defense reasserted its primacy in both Spain and Austria in 1809 under operational artists Sir Arthur Wellesley, later the Duke of Wellington, and Archduke Charles of the Hapsburgs. Wellesley, a master of defensive warfare, leveraged fortified compound warfare in Spain, which used fortified safe havens.4 Charles, on the other hand, faced Napoleon with a reformed Austrian army in 1809 that looked in every respect like the Grande Armée except that it lacked Napoleon at its pinnacle, although Charles had learned enough to defeat the master at Aspern-Essling. The defeat of Napoleon in open battle for the first time, added to the preview at Eylau two years earlier, forever vanquished the idea of Napoleonic invincibility.

This chapter examines the operational generalship of two individuals—Arthur Wellesley and Archduke Charles of Austria and changes from a focus on Napoleon to include his principal adversaries. Although Napoleon matched wits with Charles, he never directly campaigned against Wellington during this period, although Napoleon did give his marshals operational guidance from afar about how they should fight him. But first we must deal with the question of how Napoleon, victorious with all of Europe at his feet, came to fight against a former ally in Spain, the British in Portugal, and a supposedly prostrate Austria, presumably humbled and cowed after the defeats at Ulm and Austerlitz.5

THE CONTINENTAL SYSTEM AND PEOPLE’S WAR IN THE PENINSULA

Napoleon’s many decisions led to what he later regarded as one of his greatest errors, the war in the Iberian Peninsula. He remarked, after the fact, “That unfortunate war destroyed me…All…my disasters are bound up in that fatal knot.”6 His “fatal” mistakes can be traced to his animosity toward Great Britain. He never completely understood how or why his actions and policies alienated that great sea power, in part because his understanding of oceanic trade and commerce was limited to a continental outlook. At Trafalgar he had lost the capability to threaten Britain from the sea, and his disastrous experience in Egypt had taught him that straying too far from the nexus of his strength in Europe to attack British interests did not work either. He thus intensified his policy of economic foreclosure of European markets to British manufactured goods as a means to leverage Britain. This policy had actually existed during the Revolutionary Wars, but because so many of Europe’s ports remained open, it did little to help the French. After the battles of Austerlitz and Trafalgar, a stalemate between the land power of France and the sea power of Britain ensued. However, when efforts for peace fell apart and Britain joined Prussia and Russia in the Fourth Coalition (1806–1807), Napoleon intensified his economic warfare against Britain. With all of Northern Europe (except Russia) under his control, he issued the so-called Berlin Decree in November 1806, closing all the ports under French control (including those in Prussia) to British trade and seizing British shipping.7 The British responded to the Berlin Decree with their own Orders in Council that closed all British ports to shipping originating from France or transshipping through French-controlled ports. Only the ports of Portugal and Russia legally remained open to British commerce on the continent of Europe. With Tilsit the Russians joined Napoleon’s system, and the “continental system,” as historians have come to call it, was now complete with the exception of Portugal. Napoleon now turned his eyes toward that small maritime nation. His desire to get there was hastened by the British combined army-navy amphibious action against the neutral Danes that summer at Copenhagen, an attack that had effectively denied Napoleon the ability to seize that nation’s navy. Napoleon wanted to avoid having the British seize Portugal and Lisbon in the same manner, although he was more worried about a British base than any Portuguese shipping that might be seized.8

To get to Portugal one must pass through Spain, but since Spain was an ally and fearful of Napoleon’s vengeance for its perfidy in 1806, it gladly granted passage of a French army under the command of General Jean Junot in October 1807. In order to secure his lines of communication through Spain, Napoleon began a program of inserting French garrisons into Spanish cities between southern France and Portugal.9 Some of these actions were retribution against Spanish perfidy because its chief minister, Manuel de Godoy, had been scheming to abandon France and join her enemies in 1806. Jena-Auerstadt undermined that plan and the Spanish were obsequious in their reaffirmation of French allegiance, but Napoleon never forgot a slight.10

In 1807, Spain became a cauldron of intrigue as the heir to that throne schemed to depose his royal father and eliminate Godoy. Napoleon realized the problems that a change in the regime in Madrid might entail, writing to his brother Joseph in January 1808, “trouble in Spain will only help the English…and waste the resources that I get from that country [Spain].” Meanwhile Junot and about 1,500 famished troops (out of an original 25,000) arrived in Lisbon on November 30 just after the Portuguese royal family had fled with the bulk of its navy and its entire treasury to the protection of the Royal Navy off the coast. This episode should have been a warning to Napoleon of the operational difficulties of rapid maneuver in the rugged terrain of the Iberian Peninsula. The British threat dominated Napoleon’s thoughts as he pushed more troops into Spain, including a corps under General Dupont who was given orders to proceed deep into Spain, ostensibly to counterbalance English reinforcements that had arrived at Gibraltar.11 Earlier, Napoleon, under the terms of his alliance with Spain, had used the large Spanish division of the Marquis de la Romana in the siege of Stralsund. He now moved it into Denmark to guard against further British actions there. This action had serendipitously denuded Spain of some of the best troops in her army at a critical time.12

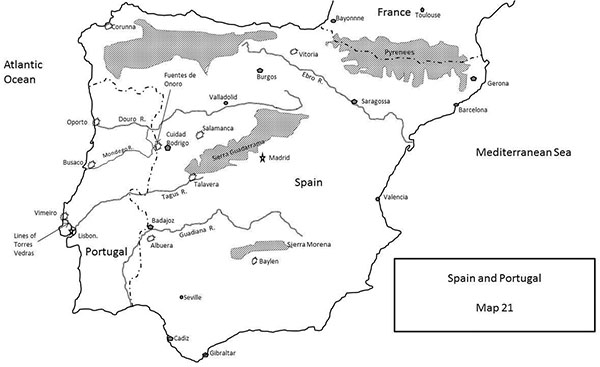

Thus, with numerous French troops scattered throughout the Peninsula and most of Spain’s best soldiers far removed to the north, Napoleon decided it was time for a change in the government of Spain. In February, through ruses and deception his troops seized a number of key fortresses along the Pyrenees and elsewhere.13 Then, after a palace coup in March 1808 caused King Charles IV to dismiss the hated Godoy and abdicate in favor of Prince Ferdinand, Napoleon used this occasion to summon all parties to Bayonne for mediation (see map 21). Once there, he deposed and imprisoned both father and son and appointed his brother Joseph, currently reigning as the King of Naples, as Spain’s new monarch. The first action was celebrated by the Spanish people, who blamed the King and Godoy for their misrule and defeats by the British, believing better times would be had with Ferdinand. However, the deposition of the popular Ferdinand rankled the masses of peasants, priests, and the proud aristocratic Spanish officer corps who still believed that God appointed kings, not French Emperors. Prior to Ferdinand’s imprisonment, Napoleon had peacefully occupied Madrid with forces under Marshal Murat. The presence of ever more French troops throughout Spain, including in places like the province of Catalonia that were nowhere near Portugal, also caused resentment, especially since the ill-supplied French troops often behaved in their normal rapacious and rude style toward the locals.14

Scholars still debate the wisdom of Napoleon’s disastrous decision to impose his brother on the proud Spanish people versus a popular and native crown prince. Some explain the decision as being made for strategic reasons as Napoleon moved onto his next project in his global war against Britain. He planned to dismember the Ottoman Empire with Austria and Russia and he wanted to secure the bases in Spain to move against the Maghreb in North Africa. Others highlight that it was a snap decision, made for ideological reasons. Spain was a backward monarchy ruling over a largely indolent class of aristocrats and masses of illiterate Catholic peasants. The disorder, ignorance, and lack of an ordered and efficient government in Spain offended Napoleon’s sense of good government. There were some liberals in the larger towns and cities, but not many—not nearly enough as it would turn out. Resentment built and Napoleon’s decision to try and enforce the Continental System at the same time as he conducted a “glorious” bloodless revolution in Spain now backfired, disastrously.15

Map 21 Spain and Portugal

On May 2, the citizens of Madrid famously rose in revolt against the hated Mameluks and other French Guard troops under Murat in Madrid. Murat brutally repressed this revolt and for about three weeks all was quiet in Spain. However, between May 20 and June 5, major revolts broke out in nearly every city and town garrisoned by the French. Aside from Junot in Portugal, which also was in a state of low-level revolt, Napoleon had over 130,000 troops scattered throughout Spain. His strategy to have Murat and his subordinates break up the organizing Spanish armies, composed of the disgruntled and disenfranchised Spanish officers of the old Royal Army, failed.

The French situation in the Peninsula went quickly from bad to worse. Conventional Spanish armies were being raised in every corner of the country and the arid countryside had now become dangerous for anything other than organized French bodies of troops as the Spanish and Portuguese peasants organized to harass and murder the hated, pagan French oppressors (as they saw it). The British government also decided to take advantage of the moment and dispatched a British expeditionary force to attempt to retake Lisbon. It was to be commanded by two elderly British generals, Sir Harry Burrard and Sir Hugh Dalrymple. Meanwhile, French arms suffered disaster in the southernmost province of Andalusia. By this time Murat, who had become seriously ill just as the revolt was breaking out, had turned over his command to one of Napoleon’s aides, General Jean-Marie Savary. At the end of May, just as revolt was breaking out everywhere, General Dupont’s corps had proceeded south toward Cadiz. He had gotten as far as Seville, which his men plundered, before being recalled by Savary. Loaded with loot, he dithered for much of the month of June south of the Sierra Morena Mountains as another column of French troops moved south from Madrid to join him. Dupont had little idea of how exposed his command was. Through a series of miscues and poor French decisions, rather than any outstanding Spanish generalship, two Spanish armies totaling over 40,000 men managed to place themselves between Dupont and his escape route north at the town of Baylen. The column under General Vedel that was to join him had marched north and left no guard at Baylen to keep the escape route open. After weak attempts to break through, Dupont surrendered his force of over 11,000 tired and dispirited troops on July 20 to the Spanish. The Spanish threatened to massacre Dupont and his men if he did not recall Vedel, who was escaping to the north. In a stunning display of cowardice and incompetence, Dupont ordered Vedel to surrender and that individual stupidly obeyed. The total bag in prisoners was over 17,000 French. Europe was stunned on hearing a French corps had been annihilated (literally, as it turned out, when the Spanish reneged on every promise and sent their prisoners to die of disease and neglect on prison hulks at Cadiz and elsewhere).16

ENTER WELLESLEY

Elsewhere in Spain, French troops found themselves cut off in cities like Barcelona or placed them under siege, as at Saragossa in Aragon. Fortunately for Napoleon Spanish efforts were ill-coordinated, but his troubles were not over. While Dupont stumbled into catastrophe in southern Spain, an English expedition sailed for Portugal. When the catastrophic news of Baylen arrived, Savary advised King Joseph, only recently arrived in his new capital, to abandon Madrid and move north to combine with the victorious forces of Marshal Bessières in Castille. On August 1, the French retreat began. That same day the British expedition arrived off Mondego Bay, about 100 miles north of Lisbon, and began landing 14,000 British regulars under the temporary command of Sir Arthur Wellesley.17

Wellesley came from the British nobility of Ireland and was the younger brother of the powerful and influential Richard Wellesley, Lord Mornington, scion of the Wellesley family. Wellesley had faced considerable challenges in his military career, due to the competition with other ambitious British officers who were often his seniors and the varying fortunes of his political allies, especially his brother Richard. As a younger officer he had participated in the disastrous British campaign of 1794–1795 in the Low Countries and according to one biographer learned that, “war was a serious business which should be undertaken in a thoroughly professional spirit or not at all. Having discovered what defeat was like, he gained a fierce determination to avoid it in [the] future.”18 Wellesley’s apprenticeship in arms continued as he followed his brother to India and gained a solid reputation with his “sepoy” victories at Seringapatam (where he was not even in command) and Assaye. Wellesley’s Indian interlude served him well for the remainder of his life. It provided him invaluable experience commanding a hodgepodge of regular British and sepoy troops, irregular native forces, in coalition with sometimes feckless native allies. It was in this environment that Wellesley first operated in both the political and military worlds. In short, it served as the ideal education for his later operations in the complex environments of Spain and Portugal. After his return to Britain in 1805, Wellesley gained further valuable experience in combined army-navy operations, serving as the second in command of the British expedition against Copenhagen in 1807 that removed that unfortunate nation’s fleet from Napoleon’s grasp.19

Wellesley shared another trait of great modern commanders, his ability to set out his ideas in writing: “Wellesley’s unusual confidence in marshalling evidence and setting out an argument in long, detailed memoranda—which had been evident ever since his early days in India a decade before—made him particularly useful as a military advisor.”20 From his experiences in India and Denmark, he had demonstrated diplomacy and tact and was always careful about his logistical arrangements—key qualifications for success in operational art. Wellesley was a hard worker, and showed (like Napoleon) that the great generals in modern times must also have a talent for hard intellectual work that is not always glamorous. However, Wellesley had significant obstacles to overcome in finally being appointed as the overall commander of British forces in Spain. He was neither esteemed by the head of the British army, the Duke of York, nor, for that matter, by King George III. Wellesley had to prove himself worthy as opportunities came his way and he made the most of every one of them. Now, at the head of 14,000 troops in Portugal his time had come, but he had to hurry. There were two British officers senior to him who could supersede him at any moment, Generals Burrard and Dalyrymple.21

Wellesley’s opponent, General Junot, now had an army of 25,000 in and around Lisbon, so the task before this impatient Englishman was of no small magnitude. His only secure route of retreat was to return to the Royal Navy ships that had disgorged his force in the first place. However, these same ships also secured his seaward flank and provided him a relatively reliable source of supplies as long as he hugged the coast in his southward advance to Lisbon. By August 5, he had begun to move south and on the August 15, collided with Junot’s advance guard, which fought a stiff rearguard action at Rolica. Undeterred by this energetic French opposition, Wellesley’s operational instincts led him to conclude that aggressive maneuver was his best course. He pushed his smaller army south to a strong position at Vimeiro where he learned he was about to be superseded by General Sir Harry Burrard. His impetuous advance had the unintended positive result of luring Junot out from Lisbon with an approximately equal number of troops. On August 21, Wellesley defeated his first French army, repulsing Junot’s spirited attack at Vimeiro and suffering only light casualties. However, Burrard superseded Wellesley after the battle, ignored his advice and cancelled orders to aggressively pursue the beaten and disorganized French. The next day, General Dalyrymple landed and assumed command.22

The British had trapped Junot literally “between the devil and the deep blue sea.” Their use of what is now called “operational maneuver from the sea” against an isolated French army with the right commander had yielded spectacular results. Using all his tact and flair for bluff, Junot convinced the two elderly British generals, against the advice of Wellesley, to agree to the infamous Convention of Cintra, whereby the French evacuated Lisbon and Portugal in return for being shipped back to France with “weapons, colors, and baggage.” Wellesley unwisely affixed his signature to this document, probably because he believed that this was the better part of wisdom given the military talents, or lack thereof, of his two superior officers. Had he not signed it they might have continued their lackluster performance and then perhaps Lisbon would have remained in enemy hands as these two old men dithered about until another French army arrived. This fear, as it turns out, was probably justified, since Napoleon had decided that Spain needed his personal attention in order to turn the tide of defeat that had overwhelmed French arms. In any case, that September the British dutifully began moving Junot’s entire force of over 25,000 troops back to France. Of these troops, 22,000 had returned to Spain by the end of the year and ended up being involved in the siege of Saragossa.23

Once the terms of the Convention of Cintra were revealed to the British public, all three generals were ordered home to face an official inquiry.24 While Wellesley fought for his professional life back in London, the British army came under the command of the highly competent and professional Sir John Moore. While Moore set about organizing a new Portuguese army and ensuring that nation’s security, Napoleon assumed personal command of the forces in Spain that fall. The details of Napoleon’s subsequent campaign need not concern us here. Suffice it to say that the asymmetry between French arms and the hastily raised and poorly led armies of Spain again came to the fore. The Spanish exacerbated this situation by letting Napoleon reinforce and reorganize his forces in Northeastern Spain to approximately 130,000 troops. After wasting the entire month of October, they advanced loosely with four armies totaling about 120,000 troops on the area of Napoleon’s concentrations in the vicinity of Pampeluna—Vitoria—Bilbao. French forces defeated them in detail, driving them in divergent directions so they could not support each other. One incident worth remarking on involved another example of British operational maneuver from the sea—gone to waste in this instance. Recall that the Marquis de la Romana commanded over 15,000 of Spain’s best troops, veterans of the war in North Germany and Poland, garrisoning Denmark against further British action there. That fall, the Marquies de la Romana contacted British agents and managed to arrange to have over half his corps evacuated out from under the nose of the French by the Royal Navy. These troops returned to Spain and became the core of the army commanded by General Joachim Blake. However, many of these men were killed or captured by Marshal Victor at the Battle of Espinosa on November 10–11 as Napoleon resumed offensive operations.25

Scattering the central Spanish army, Napoleon advanced rapidly in the harsh winter weather to retake Madrid on December 3. Rumors of a secret mobilization by his old enemy Austria started to reach him, and he found himself now trying to manage several military and political problems at once. Meanwhile, the other French armies advanced on his flanks, one placing Saragossa under siege and the others advancing into the northwestern provinces of Spain. It was at this point that the British entered Napoleon’s calculations, coming to the aid of the Spanish. Moore was soon at Salamanca and threatening Napoleon’s rear and endangering Soult’s corps to the north. The Spanish army in that region, now under Romana was supposed to cooperate with Moore, but together both proved too weak to do much of anything except delay Napoleon’s pacification of the rest of Spain and the upcoming second invasion of Portugal. This is precisely what Moore accomplished. Napoleon raced north in an effort to annihilate the only British field army of any size anywhere in the world between his forces and those of Marshal Soult. However, the cagey Moore managed to elude the trap and retreated for the safety of Coruna at the very northwestern tip of Spain where he intended to make good his army’s escape via the Royal Navy. Napoleon turned over the pursuit to Marshal Soult on January 6 and departed for France on January 17 in order to address plots in Paris and the perfidy of the Austrians, who seemed bent on war. The British retreat to Coruna in horrible weather was equally hard on both the pursuer and the pursued. British discipline broke down and when Moore arrived at Coruna, his transports were not there. By the time Soult arrived, Moore had restored some discipline to his army and occupied a strong defensive position. Although outnumbered, Soult gamely attacked and was repulsed on January 16, but Moore was mortally wounded. Nevertheless, his army was withdrawn by sea in good order. Although it had lost over 8,800 men during the brief campaign since Wellesley’s departure, it gave the Spanish and British forces still in Portugal precious breathing space and prevented the outright reconquest of both Spain and Portugal.26

As Napoleon raced to Paris he left an active insurgency in his rear. Although the French had again prevailed over conventional Spanish armies, a key difference became more apparent as the Peninsular War (as it came to be called) went along. This had to do with the inability of the French to pacify the countryside as they continued to advance and defeat each Spanish army in turn. Often the defeated Spanish troops dispersed into the numerous mountains of Spain where they joined bands of guerillas who mercilessly preyed on French communications and stragglers. These sanctuaries were another feature of what historian Thomas Huber calls fortified compound warfare.27 Thus it was in the Iberian Peninsula that the French had to fight not only regular conventional forces but also irregular guerrilla bands that plagued their rear areas and communications. Additionally, both guerillas and conventional forces often had sanctuaries to which they could retreat and build up combat power before returning to the fight. Often the prime example of this form of warfare are the Anglo-Portuguese forces under Wellesley, who turned the area around Lisbon into a fortified sanctuary in 1810 when Napoleon sent Marshal Masséna to retake Portugal. However, the war was really a series of localized provincial wars with sanctuaries in nearly every region of Spain. Some Spanish provinces were never taken at all, like Grenada and Murcia, and served as areas from which new Spanish armies sallied forth. When they did this, the French, who would spread out to pacify the countryside and battle the guerillas, had to concentrate and fight these armies. When this happened, the guerillas again occupied the terrain the French had vacated, punish collaborators, wipe out small French detachments, and generally interfere with French communications and supplies. As long as the British had command of the sea, they could supply these guerillas. As long as the guerillas had sanctuaries and supplies, they could fight. The larger the sanctuary, the larger the insurgent force. Thus, Wellesley’s Anglo-Portuguese army was not the only conventional force fighting compound warfare in Spain, numerous conventional Spanish armies were, too, for the entire period up through 1813. If we understand this dynamic, it will help us understand why Wellesley, with armies generally no larger than 40,000 men, was rarely opposed by larger French armies, despite the French having over 250,000 troops in the Peninsula at the height of the war in 1811.28

Thus, keeping all these factors in mind, the Napoleonic operational way of war, as we have described it, proved unsuited to compound war in Spain. It was designed for rapid maneuver with overwhelming force and firepower, using decisive battle to scatter and demoralize its foes, and relying on short campaigns to overcome the logistical challenges of feeding the large numbers of troops required for this approach. Like the Americans 160 years later in Vietnam, it would win just about every battle but lose the war. One can compare the North Vietnamese army to the conventional British, Portuguese, and Spanish forces and the Viet Cong to the guerilla bands. French logistics collapsed in Spain, while the watery highways off its coasts ensured a logistical flow to their enemies. Poor roads, poor weather, and an agrarian base that could barely feed itself much less foraging troops undermined the French ability to maneuver rapidly at the operational level. Thus, the French found they could advance rapidly to an objective, only to run out of supplies when they got there. It was either withdraw or starve for many a French operation. Additionally, the problems with food and logistics often prevented them from massing for the same reason, as soon as two or more corps concentrated in a small area of real estate, the French found themselves unable to feed everyone. Finally, as mentioned in chapter 5, Napoleon made all the important operational decisions for the main theater of war. This worked fine when only one theater was important, but with the campaign in the Iberian Peninsula, Napoleon could not overcome the vast distances. He could beat British and Spanish armies in one province but not in all provinces. Once he left Spain he had to rely on his generals and marshals, but he still tried to control their operations, despite the great distances. Even when Europe was at peace after 1809 he still tried to control the operations of all his commanders in Spain except in the most extreme circumstances and only for generals he trusted implicitly. Only three generals ever achieved that honor: Masséna, Soult, and Suchet. Of the three, Suchet did best, but he only pacified, ultimately, three provinces. The French never solved the difficult problem of Wellesley’s Anglo-Portuguese army operating conventionally in Portugal and Western Spain.

Returning to Wellesley: once cleared of the stigma associated with the Convention of Cintra, the British government turned to him as the sole commander of the effort to be made in Portugal after Moore’s tragic death at Coruna. He had, after all, won the only battle of any size the British had fought to date in the Iberian Peninsula and because of Moore’s daring campaign the British were still in control of Lisbon. It was not at all clear, however, that the British would even stay in Portugal. With the outbreak of war on the continent, and the chance of a decisive defeat of Napoleon by the Austrians, the topic of where to locate limited British efforts came to the fore again. Fortunately for Wellesley the decision was made to appoint him to command in Portugal with the caveat that “Lord Castlereagh [Wellesley’s sponsor in the government] will keep in view that if the corps in Portugal should be further increased hereafter, the claims of senior officers cannot with justice be set aside.”29 Thus, Wellesley knew that any hint of problem or arrival of some other senior officer could mean the end of his command. He was determined not to let this happen. Meanwhile, the British government fielded an even larger military effort to aid the Austrians by landing on the island of Walcheren in Holland with 40,000 troops in July.30 This expedition, another wasteful British effort against Napoleon’s “back door,” did little to tie down the French troops, but it did allow Wellesley time to cement his position in Portugal and Spain so that the idea of relieving him became ever more remote.

Earlier that March, before leaving England for Lisbon, Wellesley outlined for the King his operational scheme for the Peninsula. It is worth quoting the first paragraphs:

I have always been of opinion that Portugal might be defended, whatever might be the result of the contest in Spain; and that in the meantime the measures adopted for the defence of Portugal would be highly useful to the Spaniards in their contest with the French. My notion was, that the Portuguese military establishments, upon the footing of 40,000 militia and 30,000 regular troops, ought to be revived; and that, in addition to these troops, His Majesty ought to employ an army in Portugal amounting to about 20,000 British troops…. Even if Spain should have been conquered, the French would not have been able to overrun Portugal with a smaller force than 100,000 men; and that as long as the contest should continue in Spain this force…would be highly useful to the Spaniards, and might eventually have decided the contest.31

This memorandum stated the totality of his operational schema for the next four years—a defense in Portugal could be maintained with existing British manpower and could also keep the embers burning in Spain. He especially wanted a large establishment of cavalry, artillery, and engineers, thus showing his understanding of the heavy logistical and intelligence requirements for such a campaign as well as to balance those weaknesses in the Portuguese army. He also saw the need to balance out French military prowess with extra firepower. Notice its failure to explicitly mention support to irregular forces; Wellesley had yet to factor these into his operational calculus. This memorandum was remarkably prescient; as an early form of a successful war plan it has few rivals.32

Wellesley departed England on April 15, 1809 and arrived to tumultuous acclaim by the citizens of Lisbon on 22nd of that same month. He was in some hurry due to Marshal Soult’s invasion of northern Portugal and the capture of the second largest Portuguese city of Oporto.33 Upon arrival, Wellesley spent a week in conversations with the Portuguese government and resident ministers and made one of the most momentous decisions of his time in the Peninsula when he appointed William Carr Beresford to oversee all aspects of the training and organization of the new Portuguese army. The Portuguese government appointed both men as marshals in the Portuguese service and Wellesley assiduously supported Marshal Beresford’s authority in his training mission. This mission yielded a rich harvest in time by creating an effective and professional Portuguese army that soon became a major component in Wellesley’s army and critical to its subsequent success. It serves as a model for what today is known as foreign internal defense in U.S. Army doctrine.34

Wellesley’s next series of operations are justly famous and highlight his offensive character as an operational artist. Deciding that Soult was in fact dangerously isolated and ripe for a masterstroke, he rapidly marched his 20,000 British north from Coimbra on May 7 and arrived south of Oporto on May 12 with the wide Douro River presumably an impassable barrier between himself and Soult (Soult had destroyed the bridge upon receiving intelligence of the British offensive). Soult believed his forces safe because he had denuded much of the south bank of the river of boats and bateaux that could be used for an assault crossing. His forces could crush any lodgment on his side of the river before it could be reinforced. Thus, as with all generals who rely solely on the strength of their position for defense, he let his guard down and underestimated what an energetic and daring general might accomplish. Meanwhile, Wellesley sent Beresford with a force of mostly Portuguese regulars on a wide flanking movement to the east to unite with a small Portuguese army that the French had recently thrown out of the town of Amarante. The goal was to cut Soult’s line of retreat to the east toward strong French forces in Castile and drive it north and out of supporting distance into the wilds of Galicia.35

Wellesley’s assault across the Douro on May 12 under the very noses of the French was a model river crossing. He caught the French entirely by surprise and by the time they realized the threat he had strongly defended bridgeheads in two locations. Soult immediately saw his danger and evacuated Oporto to the northeast. On this route he seemed to be retreating exactly the way that Wellesley hoped to have Beresford block, but Beresford had not yet closed the trap. Here luck came into play—the French force protecting this line of retreat through Amarante had unwisely attacked the local Portuguese forces and been defeated and then abandoned the bridge to the enemy. Soult was forced to retreat further north. Wellesley now contemplated destroying an entire French corps and possibly capturing a famous marshal. But Soult was best when cornered; he abandoned all his baggage, wounded soldiers, and artillery and led his troops over rough mountain tracks to safety at the Galician town of Orense on May 19.36 Soult’s corps, initially 15,000 strong, had lost at least 2,000 men in these operations as well as most of its horses and all of its cannon. Wellesley noted in one of his dispatches that the roads were strewn with French stragglers murdered by the local peasants, “the natural effect of the species of warfare…in this country.” Wellesley further estimated Soult’s losses in total as at least a fourth of his army and that it could not possibly be able to resume active operations anytime soon.37 On this score Wellesley, like so many others, turned out to be mistaken. The operational durability of a French Corps d’Armée, in fact, came to haunt him in his very next campaign.

With Soult presumably removed from active operations for the foreseeable future, Wellesley turned his attention to the corps of Marshal Victor threatening to invade Portugal along the line of the Tagus River from Spain. Wellesley had left some British troops at Abrantes, although his orders from London prohibited actual operations inside Spain. Not far from there, the defeated army of the Spanish general Don Gregorio Cuesta attempted to recover after its disastrous defeat earlier that year at Medellin.38 Wellesley obtained permission to join with Cuesta for an offensive down the Tagus toward Toledo and Madrid. It is not clear if Wellesley aimed at a spoiling operation to further prevent an invasion of Portugal that year (1809). But his purpose included developing a military relationship with his Spanish allies and a joint offensive might help their cause in many ways elsewhere in Spain.39

The campaign that summer proved an education for all concerned. Wellesley hoped that the dispersed nature of the French forces facing him might give Allied arms a reasonable chance for an operational success. Also, the Fifth Coalition seemed to be winning its war against Napoleon, especially given Napoleon’s recent defeat on the Danube in May at the Battle of Aspern-Essling.40 Cuesta had approximately 30,000 troops, although of varying quality in both soldiers and leaders, and another Spanish army of 20,000 faced General Sebastiani’s corps in La Mancha. Wellesley did not reckon that the corps of Ney, Mortier, and especially Soult in northern Spain could provide any aid to Victor and Sebastiani who guarded King Joseph (now in Madrid again). All told, the Allies theoretically faced 50,000 French with 80,000 Anglo-Spanish troops that included 25,000 veteran British soldiers, fresh from a recent victory. But Wellesley did not count on the pride and jealousy of his Spanish allies. He also learned, to his dismay, that the Spanish promises to support him logistically were empty and he almost cancelled the campaign on these grounds alone. The elderly Cuesta did not want to take orders from a young British general (Wellesley had just turned 40) and wanted to capture Toledo and possibly Madrid, often ignoring Wellesley’s advice. One moment he was all caution, the next rash. Worse, the army facing Sebastiani failed to pursue that general when he left a small rearguard and came west to reinforce Victor. King Joseph, meanwhile, ordered the three corps of Mortier, Soult and Ney (under Soult’s command) to abandon Galicia and cut off the Anglo-Spanish retreat to Portugal. A potential disaster was in the making. 41

By July 23, the Anglo-Spanish army had come as far as Talavera where it caught up to Victor. That marshal wisely retreated to the east to join forces with King Joseph’s small reserve and Sebastiani’s corps. By the end of the month, Wellesley had established a defensive position at Talavera as Cuesta had advanced alone against the French. Cuesta soon learned he faced an army of 46,000 veteran French soldiers under Marshal Victor who had already beaten him earlier that year at Medellin. He promptly fell back and joined Wellesley at Talavera. There Wellesley fought a two-day defensive battle on July 27–28 against Victor’s army, probably the best French army that Wellesley faced in his entire career in Spain in terms of the quality of the troops. The result was a tactical victory for Wellesley. It had been a hard-fought engagement, especially on the first day when Victor had some momentary success against the British left, and the British cavalry had performed poorly. The Spanish too had been shaken, but after the first shock of battle, settled down and held firmly in their position on Wellesley’s right flank. It was the bloodiest engagement for the British army in almost 100 years. The French lost approximately 7,600 men, the British 5,300, and the Spanish around 1,200. Victor reluctantly pulled his defeated forces back toward Madrid in good order.42

Now the combined corps of Soult, Ney, and Mortier moved against Wellesley’s route of retreat. Fortunately, Cuesta had placed some troops guarding the key pass through the mountains south and these notified the Allies of the approaching danger. Wellesley withdrew his forces to safety up the Guadiana River, leaving Cuesta to his own devices in the area of Spain to the south of the Tagus. The British public and government, still celebrating Wellesley’s victory at Oporto, now feted him as the hero of Talavera. It was at this time that he was elevated to a peerage, becoming Viscount Wellington of Talavera.43 It was a hollow consolation for a failed campaign. Wellington (as we shall now call him) now retreated through some of the most barren country in Spain toward Portugal and his army suffered accordingly, especially from lack of supplies. As Wellington brought his sullen and underfed army back to Portugal, he pondered the operational lessons he had learned: that coordination with the Spanish proved difficult and that he must have absolute command over the forces under him; that he must carefully arrange for his logistics as he advanced through the famished interior of Spain; that he must secure his flanks; and that his army could not remain long in the Peninsula if it engaged in the sort of slugfests that Napoleon and his marshals were willing to fight. He innately recognized that the contest in the Peninsula depended on continued support from back home and the steady application of pressure from a position of strength, in short that operating on the strategic defensive was probably his best course of action for the future—fighting a campaign of “erosion,” or attrition. He also learned of Napoleon’s triumph on the Danube at the hellish Battle of Wagram, the bloodiest battle in European history since Lepanto (1571). He knew well enough that he needed all his skill and luck to face the coming storm in 1810 as new French forces would surely be diverted to Spain to cure once and for all the “Spanish Ulcer.”44

OPERATIONAL ART ON THE DANUBE

When we last heard from the Emperor of the French, he was racing north to deal with an Austrian rebellion against his European hegemony. We must now rewind the clock and address the primary theater of war in 1809 along the Danube and consider what had changed in warfare that made this year a turning point in the history of war. The argument is made best by Napoleonic scholar Robert Epstein, who contends that the Austrian army of 1809 represented a symmetrical counterweight to Napoleon’s system, opposing him with a force designed specifically to take advantage of those factors which hitherto the French had benefitted from as a result of the changes wrought by the French Revolution and Napoleon. Epstein claimed: “Napoleon would face a modern army rather than an antique one for the first time in his life.”45

To understand the new Austrian army’s ability to challenge the Grande Armée on relatively equal terms, we must return to the disasters of Ulm-Austerlitz and their aftermath. Recall that Austria signed a humiliating peace in 1805 with Napoleon, parting with large territories as Napoleon aggrandized his own empire as well as the domains of his allies, such as Bavaria. Nothing serves so well for meaningful military reform as failure. Such had been the case with France after the Seven Years’ War and soon, as we shall see in chapter 7, with the Prussians after the catastrophe of 1806–1807. For the Austrians the interwar reform period came between 1805 and 1809. The key individual in this regard was Austria’s most competent military professional, the brother of Emperor Francis, Archduke Charles.46

Charles had tried to implement reforms prior to the War of the Third Coalition, but had been stymied in many of his suggestions, although he and Mack had managed to at least formalize the use of the combined arms division. They also, at the last minute, had established a formal, permanent general staff.47 However, more was needed and the “polyglot” Empire of Austria was forced to take some of the measures taken by the French in order to once again challenge the French. The first and probably least successful reform involved conscription, which proved difficult for the Austrians given the wide spectrum of nationalities. They had medieval-era militia levies that could be called out in extreme emergencies—the Ban of Croatia and the Insurrectio of Hungary—but these were essentially untrained levies and cumbersome to activate. They played no great role in the campaign of 1809, although they might have had the war continued into another season.48 What Charles did do was increase the size of the regular army and create a limited trained militia, the Landwehr, from the German-speaking provinces in Austria. These came about 40,000 strong and contributed 15,000 troops for use along the Danube. Charles had to hand in January 1809 an impressive force of over 400,000 trained troops that could challenge Napoleon, who had numerous forces tied down in Spain and garrisoning areas of the coasts (such as Holland) and Germany (especially Prussia).49

More important were the organizational changes that Charles implemented. These included creating, as had Napoleon, artillery and cavalry reserves for use both tactically and operationally. In addition, he increased the artillery to more than 700 guns and would have superiority in this arm over Napoleon during the campaign. Charles concentrated the control of this numerous artillery at the higher echelons of brigade up to the army level. Charles intended to offset French élan and numbers with fire power. Another French innovation the Austrians adopted was the combined arms corps, which included cavalry, artillery, infantry, and engineers. Charles additionally beefed up the Quartermaster General Staff (QMGS). The QMGS included talented officers like Josef Radetzky, whom the Emperor appointed chief of staff in 1809. Charles also oversaw the professionalization of his logistics service, making their leaders commissioned officers in the Imperial Army. In the area of doctrine, Charles adopted French skirmishing tactics, including them in the field regulations and substantially increased the number of independent light infantry (jaeger) battalions. He also created a new tactical formation known as the “mass” composed of two companies that could advance rapidly on the battlefield prior to forming line and in doing so could defend itself reasonably well against cavalry attacks. This gave the Austrian army a new level of tactical mobility on the battlefield that proved a surprise to the French in 1809.50

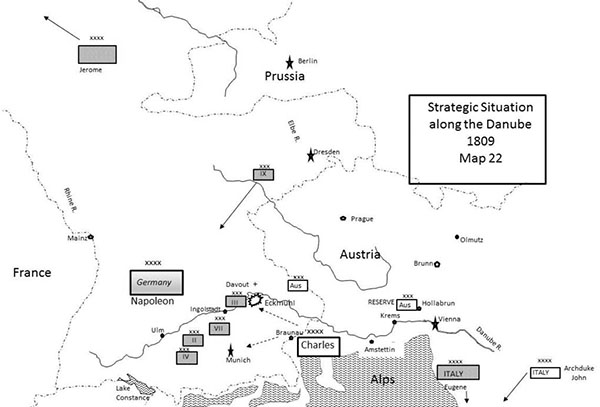

As a leader, Charles resembled more an 18th-century general in his caution and planning. His reforms, however, gave him the tools to qualify as an operational artist despite this presumed weakness.51 As mentioned, with this new army Kaiser Francis I now felt he could challenge the French, especially given their setbacks in Spain. Accordingly, on April 9, 1809, Archduke Charles invaded Bavaria with his new operational tool. Unlike Napoleon, he still dispersed far too much of his “mass”—sending two corps to mask the army of Prince Eugene Beauharnais in Italy, one corps to contain the Polish forces in the Grand Duchy of Warsaw, two corps north of the Danube and the remaining six corps (127,000 troops) with him south of the Danube advancing on the scattered French forces under Marshal Berthier in the bend of the Danube near Eckmühl (see map 22).52

Map 22 Strategic Situation along the Danube 1809

Napoleon, still in Paris (but soon notified by his excellent semaphore telegraph system) had about 170,000 available troops—but half of them were new conscripts and many of his best generals were in Spain. Also, 50,000 of these troops were Germans, although they fought reasonably well in the upcoming campaign. Charles clearly committed too many troops to the secondary theaters, a total of over 100,000 soldiers in Poland and Italy as compared to opposing French forces who totaled fewer than 40,000. Because of this error he was outnumbered along the Danube in everything except artillery.53 Charles’s timing and location for his attack (if not his massing of his forces) proved fortuitous, especially since Napoleon had not yet joined his army. Berthier’s confusing orders in the absence of his master had caused a gap in the middle of the French deployment that Charles now marched into, in some sense he had achieved what Napoleon had done four years earlier at Ulm. However, he did not realize his good fortune and instead of destroying each French corps he in turn blundered into a lengthy four-day contest against the defensive expert Davout, whose large corps fought a masterly delaying action in the vicinity of Eckmühl (April 19–22). The one positive result was the capture of the crossings over the Danube at Regensburg that allowed Charles to bring his two northern corps down into the fight as Napoleon fixed the Austrians at Eckmühl in an attempt to build up strength to move on Charles’s left flank and rear. Napoleon’s options were limited as his various echelons moved up to the fight. By April 23, Charles was beaten, although the battle had covered a very wide front and the Austrian artillery exacted a fearsome toll that Napoleon had not anticipated. Charles withdrew most of his forces to the north bank of the Danube, sacrificing his cavalry reserve to delay Napoleon’s superior forces. The character of these operations involved corps-sized maneuver by both sides, sequential and almost constant combat over a wide front, and lack of a decisive operational victory, even though Davout, as usual, succeeded tactically.54

Charles retreated to Krems, his army dispirited but not destroyed. The Napoleonic paradigm of the durable operational formation, in this case Charles’s new army, now applied to the Austrians as well as the French.55 However, all was not lost. Eugene had been driven back in Italy and the entire Tyrol, which had been ceded to Bavaria in 1805, had (like Spain) risen in revolt, tying down further forces to aid in the threat to Napoleon’s southern flank. Napoleon might have done well to have crossed the Danube and destroyed Charles’s army, but the distractions of other theaters (to say nothing of Spain) led him to proceed as he did in 1805, along the southern bank of the Danube toward Vienna. Also, Napoleon was somewhat relieved that his army had not suffered more damage from the nasty surprise Charles had just administered. In failing to pursue à outrance as after Jena, the emperor gave Charles time to regain his composure and restore his army’s fighting spirit and strength. Charles had advised his imperial brother to make peace after the setbacks south of the Danube had disabused him about the optimism over Napoleon’s recent setbacks in Spain. Francis was made of sterner stuff and the fact that Napoleon did not pursue was perhaps evidence, which Charles had not noticed, that the French had suffered, too, from the recent combats. As if to emphasize this point, the French pursuit caught up with Charles’s one corps on the south bank of the Danube at Ebelsberg on May 3 under Baron Hiller. The Austrians fought a bloody rearguard action against Masséna, then retreated across the river to join Charles, destroying the bridges as they went.56

The first phase of the campaign was over. The second phase now began. On May 10–12, Lannes’s corps arrived at Vienna and captured those portions of the city on the southern side; however, he did not repeat his coup of 1805 and capture the bridges, thus separating Napoleon from his quarry by the wide Danube.57 Vienna was well-stocked with provisions, which solved some of the logistical problems created by Napoleon’s rapid advance, but Napoleon had not defeated the bulk of the Austrian army on the other side of the river. As Napoleon gathered his forces in Vienna for a crossing of the Danube, news came in from other quarters, both good and bad. On the plus side, Eugene had been able to force Archduke John’s army away from Italy to the west and General Marmont’s independent corps in Dalmatia had prevailed against the Austrian forces that had attacked it. Also, the Poles under Josef Poniatwoski had defeated the Austrians before Thorn and then invaded Galicia causing a pro-French rebellion in the province against the Austrians. More worrisome was news from north Germany, where a corps under the dispossessed Duke of Brunswick, built around troops the Austrians had allowed him to raise in Bohemia, had led a revolt inside the French puppet Kingdom of Westphalia against Napoleon’s brother Jerome. Another revolt occurred in north Germany led by the Prussian cavalry officer Major von Schill. The Prussian army did not support Schill, whose revolt was put down by Danish and Dutch troops rather easily. Brunswick proved more problematic but order was restored in Westphalia with most of its new army remaining loyal to Jerome. The British, though, evacuated Brunswick’s “corps” by sea, promptly transporting these forces to Spain where they came under the control of Wellington.58

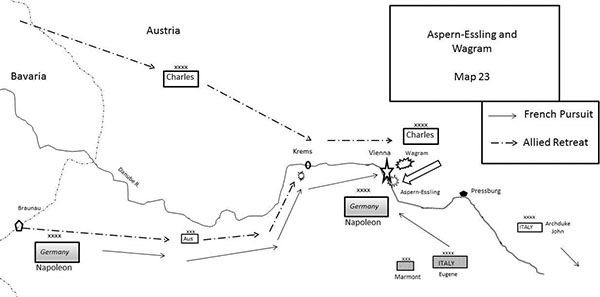

As his forces closed up on Vienna, Napoleon, almost haphazardly, began to cross the Danube on May 20 downstream from Vienna by constructing bridges to the Island of Lobau and from there to the north shore near the villages of Aspern and Essling (see map 23). Charles moved to counter this, gathering over 95,000 troops and 292 guns just inland with a view to annihilating the French after the first corps had crossed the rivers. The Austrians had already launched several ships down the Danube to try to break the pontoon bridges spanning the river to and from Lobau. With either exquisite timing or extreme serendipity, one of these broke the main pontoon the French were crossing at midday on May 21. This event cut Napoleon, Lannes, and Masséna off on the north bank with 20,000 troops as Charles unleashed his offensive. Desperate fighting broke out all along the front at 1430 hours, just as the French repaired their bridge and Lannes’s corps began to cross to join their leader. Had Charles attacked a bit earlier in the day he might have annihilated the French before reinforcements arrived, although some observers believe Charles wanted more French to cross the river before he cut them off to make the victory more complete. However, with the bridge fixed the French were able to restore the front and recapture Aspern as night fell. Napoleon was in large part saved by the strength of his position defensively, anchored by the two towns, and the fact that some of his best marshals were in the pocket with him leading the troops—Masséna, Lannes, and Bessières with the cavalry.59

Map 23 Aspern-Essling and Wagram

The contest remained undecided and resumed the next day (May 22) with equal intensity. Napoleon seemed to be winning as his echelons from across the river continued to cross and reinforce his strong defensive position—it seemed another Friedland might be in the offing. However, again, Charles broke the bridge, this time with a giant floating mill. Napoleon remained trapped on the northern shore with 55,000 troops against Charles’s 90,000. Ammunition began to run low and Charles personally led his men forward to attempt to complete his victory. The fighting was fierce and Lannes mortally wounded. Once the bridge was restored, Napoleon pulled back, giving Charles the first victory that anyone had ever achieved against Napoleon personally on the battlefield. The losses were immense—21,000 French and 23,000 Austrians—primarily due to artillery fire and the close-quarters fighting in the villages. The Austrian losses might have been higher if not for Charles’s new tactical formation that gave his infantry a large measure of protection against Bessières’s furious cavalry charges.60

The impact of this defeat on the two sides provides an interesting contrast between Charles and Napoleon. Charles urged his brother to make peace, believing that with this victory the Austrians could get a just settlement. Francis I did not see it that way and continued the fight, believing that he might gain more instead of losing all. Napoleon’s reaction was to redouble his efforts to solve the problem of how to come to grips with Charles’s army. At the same time, he had a vast empire to defend with fronts in Spain, Germany, the Balkans, and Poland all active at the same time. It is a testament to his military and political institutions that, in every case, as we saw earlier, the forces not directly under his command (other than in Spain) prevailed. Eugene defeated Archduke John at Raab on June 14. The campaign, now in its third and final phase, involved a race between Charles and Napoleon to build up combat power for the final match. Napoleon won that race in July when the army of Eugene and Marmont’s corps both gave their Austrian counterparts the slip and joined him near his new and more numerous bridges on the Danube near Lobau. These detached forces constituted a second operational echelon that gave Napoleon the decisive advantage in the next round of combat.61

Charles’s plan seemed to have been the same, to attack Napoleon’s forces as they attempted to cross the river. However, with French forces in possession of a crossing further down the river at Pressburg, Napoleon employed operational deception to get the jump on Charles in crossing the river. Charles’s key mistake after Aspern-Essling was his failure to assault Lobau and prevent its use by the French, since the Danube at that location was narrower and easy to bridge. On July 3–4, Napoleon began to increase the sizable forces he already had garrisoning Lobau, screening his movements with a squadron of gunboats that both protected his crossing and denied the Austrians both intelligence as well as their efforts to break the bridges to Lobau. Charles was fooled into thinking Napoleon would cross at Pressburg, but these forces, including Eugene, countermarched up the river for the crossing at Lobau. By July 3, Charles knew Napoleon would probably cross from Lobau, but even there he could not be sure where to meet Napoleon’s forces given that Napoleon had occupied a number of smaller adjacent islands from which he could easily reach the north bank of the Danube. This is precisely what Napoleon did, choosing to cross the new bridges located in a different part of Lobau on July 4–5 (with a prepared floating pontoon bridge) instead of debauching on the old Aspern-Essling battlefield. Aside from covering forces, Charles decided not to contest the crossing and pulled back into a nearly 10-mile defensive position on the heights north of the broad Marchfeld plain. The subsequent Battle of Wagram on July 5–6 was a two-day affair between Napoleon’s 189,000 troops and 488 guns and Charles’s 136,200 supported by 446 cannon. It played out as a brutal slugfest, with artillery becoming the primary weapon of death. Never had Europe seen such an artillery barrage in its history. By the end of the second day, Napoleon had persevered through sheer, brute attrition. The Austrian cavalry reserve, decimated in the first phase of the campaign played no great role, with remounts having been hard to obtain. Overall losses for both sides were appalling, 32,000 French casualties and 40,000 Austrian, many of these from giant batteries Napoleon emplaced close to the Austrian lines to blow holes in them. Charles fell back and agreed to an armistice that allowed Napoleon a chance to recover from his bloody “victory.” Francis, meanwhile toyed with the idea of continuing the fight from further east in Hungary since the Tyrol remained unpacified and the British had invaded Holland. Worse, he removed Charles from command, but had no one of equal talent to replace him with. By October, though, he had lost hope and signed a humiliating treaty (Pressburg) that stripped Austria of even more territory, made her a military ally of the French, and reduced her army to a maximum of 150,000 soldiers. Napoleon subsequently married Francis’s daughter Marie-Louise in 1810 to seal the deal of the new Franco-Austrian entente and to secure an heir after divorcing Josephine.62

Napoleon seemed to have triumphed over Charles and the Hapsburgs. But he, too, realized something had changed. The decisive Napoleonic battle had become the attritional Napoleonic campaign. He and his adversaries learned that in this new style of warfare whoever had the most resources prevailed. Also, the temper of the battlefield had changed. Ever since the destruction of Augereau’s corps at Eylau and then Bagration’s corps at Friedland by massed artillery, this arm had increased in its killing power until the ultimate example of Wagram, where nearly 1,000 cannon thundered constantly for two days. One sees Sedan in 1870 and even the opening days of World War I previewed at Wagram. Napoleon made the decision to increase the firepower available to his troops after this campaign, reintroducing cannon to the lower tactical level of the regiment, thus pushing his combined arms revolution down echelon as well as up.63 Napoleon rebuked a minister who impugned the Austrian military in later years, “It is evident that you were not [italics mine] at Wagram.”64 The late historian Russell Weigley and his student Robert Epstein both argue that Wagram represented a turning point, where the allure of decisive battle dimmed as battles became less and less decisive while warfare expanded in scope and became attritional. One could no longer win the campaign in one or two battles, or in battles of one day’s duration. One could no longer win by destroying a division or corps, one had to destroy the entire field army, and even this might not be enough if the enemy had other armies to hand, or as a Russian operational theorist might put it, other operational echelons available in the deep rear.65 In central Europe, as in Spain (and soon in Russia), war had assumed an absolute, attritional nature with these developments.

* * *

The period 1808–1809 witnessed war and politics on a scale and variety not seen in Europe since the time of Charles V or the Roman Empire. However, the canvas for Napoleon’s masterpieces, to recall our metaphor, had grown too large, and his method had been copied and improved upon by the other great generals of the era. Napoleon’s adversaries, who had long studied his methods, soon came into their own—excepting Wellington, who had already arrived. Napoleon, although still learning, was learning less quickly. Politically he seemed in a somewhat better position in 1810, but the war still raged in Spain and Great Britain, mistress of the seas, remained actively bellicose. Russia, which had remained guardedly neutral in 1809, soon openly rebelled against Napoleon’s “antieconomic” Continental System. Napoleon’s ruinous strategy against Britain was soon to make the specter of a two-front war permanent.66