6

Intangibles and the Rise of Inequality

This chapter suggests a relationship between the increasing importance of intangible investment and the widely documented rise in the many types of inequality seen in recent decades in many developed countries. We argue that the rise of intangibles might be expected to increase inequality both of wealth and income. Increasingly intangible-intensive firms will need better staff to create synergy with their other intangible assets: better managers, better movie stars, better sports heroes. Firms will screen them more thoroughly and pay them more handsomely. As for wealth inequality, the spillovers from intangibles make living in cities even more attractive, forcing up housing prices and wealth for those fortunate enough to own. More speculatively, we suggest that the cultural characteristics required to succeed in an intangible economy may help explain the socio-economic tensions that underlie populist politics in many developed countries.

One of the most debated economic issues of the 2010s is inequality. According to the painstaking work of Thomas Piketty, Anthony Atkinson, and others, the rich (in terms of earnings and wealth) have over the past few decades been getting richer, and the poor poorer. And other dimensions of inequality have become more salient: inequalities between generations, between different places, and between elites and those who feel alienated and disrespected by modern society. Perhaps this multidimensional element to inequality is why it has such huge public resonance. The news provides a steady stream of stories about billionaires buying £150-million apartments in London and Manhattan, juxtaposed with reports of people in “left-behind” communities falling prey to opiate addiction, embracing political extremism, and dying young.

Many reasons have been proposed for why inequality is increasing, from new technologies to neoliberal politics to globalization. But as we’ve seen in the past few chapters, there is a deep and long-term shift going on in the nature of developed economies because of the rise of intangibles. Might this also have contributed to levels and different dimensions of inequality that we see in today’s societies?

In this chapter, we’ll argue that the growth of the new intangible economy does indeed help explain the types of inequality we’re currently seeing.

Inequality: A Field Guide

Economic inequality is a hydra-headed beast. It’s helpful to differentiate between a few different sorts of inequality that crop up in the public debate, and these are set out in box 6.1.

Box 6.1. Measures of Inequality

To clarify the types of inequality it’s helpful to distinguish between two economic concepts: income and wealth. Incomes are earned by labor and by capital (an asset) and are a “flow.” The incomes of labor consist mostly of earnings. Incomes of capital are rental payments and dividends, both being flows of payments received over a time period. Wealth is the value of assets/capital owned, which is a “stock.” For households, wealth is typically a house; for businesses, the tangible and intangible assets owned and used in production. The flow is computed from the stock by means of a rate of return: your capital income is your wealth times the rate of return you are earning on wealth. You can think of your labor income flow in terms of rates of return as well: it’s the rate of return on your stock of “human capital.” Wealth capital is typically the result of saving and inheritance, human capital of education and talent. Data show that in developed economies labor income is typically about 65–75 percent of total national income (also called GDP), the rest being capital income. The annual return on wealth is around 6–8 percent, so total wealth is about 400 percent of GDP/total income. How can wealth be so much larger than GDP? Wealth is a stock and is accumulated over potentially many years of building assets. GDP/income is an annual flow. Finally, as the Institute for Fiscal Studies notes, wealth inequality is much higher than income inequality. The wealthiest 10 percent of households hold 50 percent of the wealth. The least wealthy 25 percent of households hold almost no wealth at all. The Gini coefficient, which is a summary measure for how unequal a distribution is, ranges from 0 to 1, where a measure of 0 is equality and 1 is where only one person accounts for the entire measure. The Gini coefficient is 0.64 for wealth and 0.34 for net income (Crawford, Innes, and O’Dea 2016).

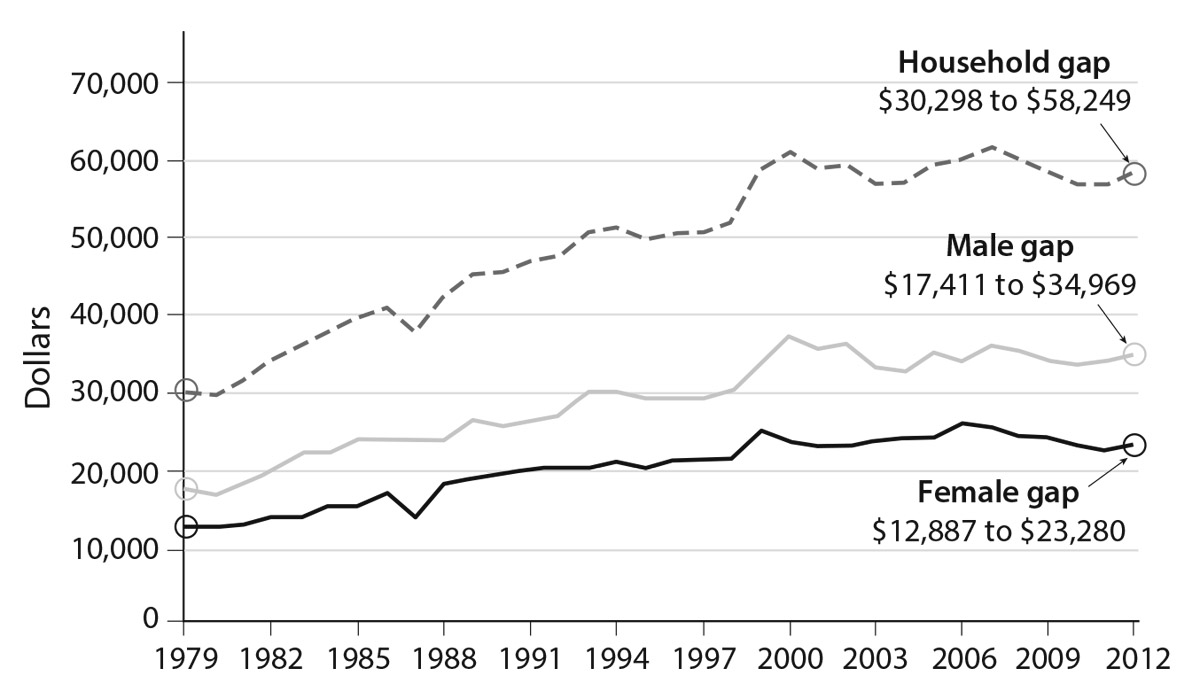

The first and most obvious type is inequality of earnings. In the UK and the United States, there was a big rise in earnings inequality in the 1980s and 1990s; inequality has remained at this higher level since. Developed countries have also seen a rise in the income gap between educated and poorly educated workers since the 1980s. Figure 6.1, showing data for the United States, is representative of many, but not all, countries: in 1979, college-educated men earned around $17,000 more than those with only high school educations; by 2012 that gap was almost $35,000 (adjusted for inflation).

But this is not just a case of graduates doing well. The power of the Occupy Wall Street movement’s slogan “the One Per Cent” was that it crystallized in people’s minds that income inequality today seems to be fractal. The incomes of the richest 1 percent, the richest 0.1 percent, and the richest 0.01 percent have risen by even more dizzying levels (see below). And as development economist Branko Milanović pointed out, this is part of a global phenomenon: over the past two decades, incomes have risen sharply for most people in the world, in particular people in big, once-poor countries like China (Milanović 2005). The world’s richest people have done well too. But one big group has not done as well: people between the seventy-fifth and ninety-fifth percentiles of world income—which represents a lot of the traditional working class in developed countries.

Thomas Piketty’s blockbuster book added another flavor of inequality to the mix: inequality of wealth. One of the many dazzling features of Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century (2014) and the research that underpins it was the light it cast on the wealth of the very rich, which is often hard to measure. It will not come as a huge surprise that this showed that the wealth of the richest in countries like the United States, the UK, and France has increased dramatically in the past few decades.

Three other sorts of inequality seem to matter to people too, even if they have received less attention in the mainstream economics debate on inequality.

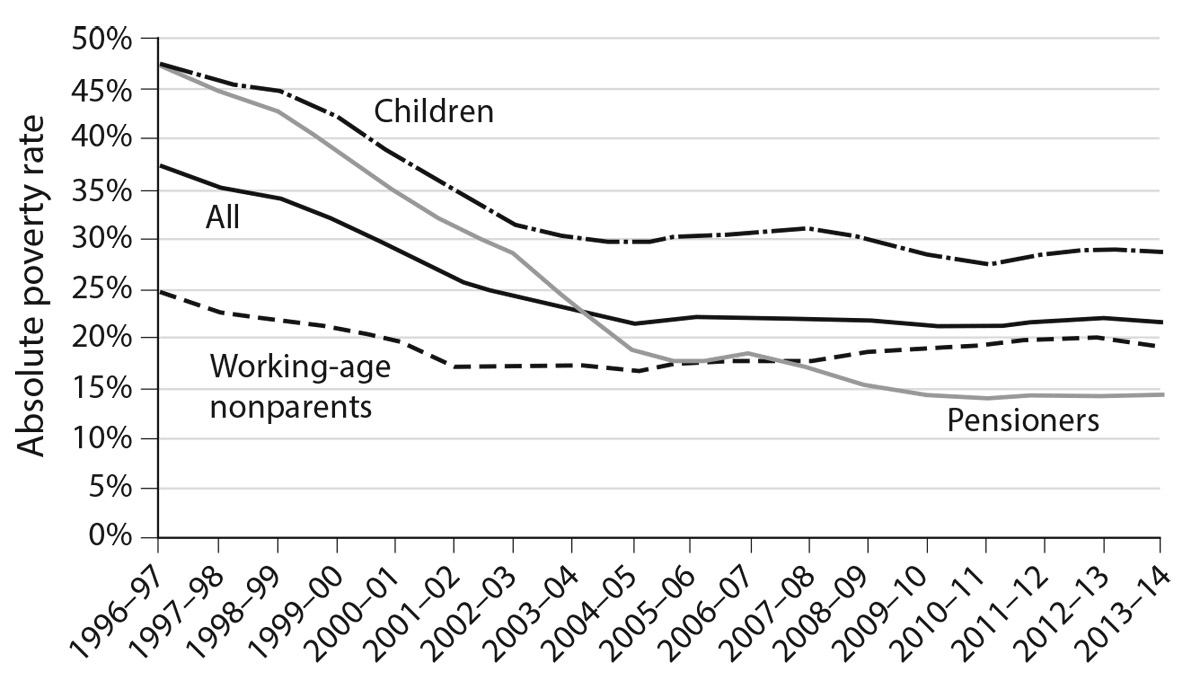

First, there has been a rise in inequality between the generations. In the UK the picture is particularly stark and well documented in the David Willetts’s influential book The Pinch (2010). For example, as figure 6.2 shows, in the 1950s the poor were overwhelmingly pensioners (along with relatively small numbers of unemployed and low-wage earners). Now the situation is completely changed. Pensioners, particularly in wealth terms, are some of the richest people in the country, while the ranks of the poor are dominated by low-paid workers.

Another dimension is rising inequality of place, even within developed countries. There is nothing new about industrial decline making once rich places poorer, least of all in Britain, where it was a problem for most of the twentieth century. Nor is there anything new about certain places being hotbeds of economic activity. But events like the 2016 Brexit referendum in the UK, where thriving cities voted one way and the rest of England another, and the election of Donald Trump on the back of a surge of votes from so-called left-behind communities away from America’s prosperous coastal cities, make this divide more salient.

Figure 6.2. Inequality between the generations, UK. Data are absolute poverty rates after housing costs (share of group below 60 percent of real median income in 2010–11). Source: Data from Institute for Fiscal Studies, Belfield et al. 2014, https://www.ifs.org.uk/uploads/publications/comms/R107.pdf.

The divides revealed by the UK’s Brexit referendum and the election of Donald Trump also point to a different form of inequality, one that economists typically focus on little, if at all. That is inequality of esteem. The reasons for the rise of populist political movements around the world, from the supporters of Donald Trump in the United States, to Britain’s United Kingdom Independence Party, to the Five Star Movement in Italy are many and varied. But one thing many of their supporters repeatedly invoke is their anger at being patronized and disrespected by what they perceive as an out-of-touch, technocratic, even degenerate Establishment. Some of the supporters of these movements are undoubtedly also poor in income or wealth terms—but not all. The inequality that fuels their anger seems to be as much about regard as about money.

The Standard Explanations

Economists have developed a number of explanations for the rise in inequality. Three of the most prominent are the rise of modern technology, the rise of globalization, and the basic tendency for wealth to accumulate.

The first story holds that inequality is the result of improvements in technology. New technologies replace workers, which means wages fall and profits rise. Modern versions of this story focus on the big technological trend of our age: computers and information technology. In the workplace, so the story runs, computers are particularly good at replacing routine tasks: switchboards in telephone exchanges, repetitive tasks on production lines, giving out money at a bank. And in the last years computers have gotten even smarter: issuing boarding passes, checking you out at supermarkets, and answering routine questions over the phone. As these computers have gotten cheaper and cheaper, it’s become more and more worthwhile for firms to replace low-skilled workers with computers. Demand for those workers has fallen and so, therefore, have their wages.

More recently, Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee (2014) have warned that, because of the speed with which information technology improves, computers may start replacing humans much faster than we are used to. This “race against the machine” or “rise of the robots” could be expected to make poorer workers redundant, to the benefit of rich capitalists.

It’s a story as old as the industrial revolution itself, and back then it gave rise to the mythical figures of Ned Ludd and Captain Swing. Modern economists, displaying an admirable flair for taking something exciting and giving it a boring name, called this trend “skills-biased technical change.” Labor market economists, particularly Martin Goos, Alan Manning, and David Autor, have suggested a twist on this story that computers are especially good at replacing routine tasks. The twist is that computers don’t replace high-paid knowledge workers, but they are not necessarily replacing the low-paid either. The reason is that many currently low-paid tasks are distinctly nonroutine: waiting on a table, cleaning a bath, or looking after the elderly. Rather, the routine tasks that computers are good at tend to be middle-income jobs, and so they “hollow out” the labor market by replacing middle-income workers (Goos and Manning 2007; Autor 2013).

The second explanation for modern-day inequality focuses on trade. It was vividly described by the economist Richard Freeman as “The Great Doubling” (2007). As he points out, in the 1980s, before the collapse of Soviet communism and before China and India moved to market reforms, the global trading economy consisted of around 1.46 billion workers in the developed countries and some parts of Latin America, Asia, and Africa.

Then, more or less all at once in the 1990s, came The Great Doubling. China, India, and the ex-Soviet bloc joined the global economy. This change increased the size of the global labor pool to around 2.93 billion workers, almost exactly doubling it. When the supply of something increases, all other things being equal, economists expect the price to fall.

And so it came to pass: these new entrants to the global labor market were employed producing goods that require relatively little skill (textiles and bulk steel, for example, rather than aircraft engines and semiconductors). This put pressure on lower-skilled workers making the same kinds of goods in developed countries, and many lost their jobs or saw their pay stagnate. This is a staggeringly good outcome for people in poorer countries, as Milanović’s (2005) research shows: the last two decades have seen a huge and long-overdue rise in prosperity of the developing world. But the working classes in the developed world have, it is argued, borne most of the costs. Immigration can play a similar role, increasing competition for low-skilled jobs (especially between new and recent immigrants).

The third explanation for today’s inequality, focused on wealth inequality, is more basic: it is the idea that capital tends to accumulate unless some countervailing force prevents it. Piketty’s now famous r > g inequality (explained in box 6.2) implies that if returns on capital (r) exceed the growth of the economy as a whole (g), then the slice of the economic pie owned by the rich will generally grow. Piketty argues that in the postwar period, political choices reduced r: in particular, high taxes on the rich and government policies that encouraged full employment and union rights. The reversal of those policies and the fall of economic growth have shifted economies to where r now exceeds g and will continue to do so.

Box 6.2. An Outline of Piketty’s r > g Condition

A sketch of Piketty’s argument, from a brilliant review by the economist Robert Solow (2014), is this. We want to find out whether the slice of the economic pie going to capital, the capital/income ratio, is rising or falling. Suppose national income is 100 and growing at, say, 2 percent. So income is growing from 100 to 102. At the same time saving and, therefore, investing grows capital as well: suppose saving is 10 percent of income this year. Thus capital is growing by 10 (10 percent of 100). The only level of capital that keeps the capital/income ratio constant is if capital is 500 (so the capital/income ratio is 500/100 = 5 in the first year and 510/102 = 5 in the second year). It follows that if the savings rate “s” equals the economic growth rate “g,” s = g, the capital/income ratio stays constant. It further follows that if g falls, perhaps because scientists run out of ideas, and s remains the same, then s > g, in which case the capital/income ratio rises. Piketty argues this will happen over the next century. The link with r > g is that, as we discussed in box 6.1, the earnings of capital holders equals the rate of return (denoted “r” by Piketty) times the capital they own. So if the capital/income ratio rises, and the rate of return does not fall, then the owners of capital will get an increasingly large share of the economic pie: this dimension of inequality, therefore, rises. Piketty’s critics have mostly argued that capital returns would likely fall if there was more capital around.

Four Problematic Stories

Technology, trade, and the tendency of wealth to accumulate: while all three of these explanations for modern levels of inequality seem plausible, there are aspects of today’s distribution that the simple versions, at least, don’t seem to explain.

Let’s consider four phenomena that are hard to square with the standard explanation of inequality: the unpredictable relationship between technology and wages; the continuing rise of the one percent; the disproportionate role of housing prices in inequality of wealth; and the importance of differences in wages between firms.

Consider technology first. We saw earlier that the idea that technology would replace jobs and impoverish workers is far from new. The other thing history shows us is that this idea is not always correct.

In mid-nineteenth-century Britain, economists worried not about robots and computers but about mules. Mules are machines for spinning cotton fiber into yarn, an important job in the textile industry, which sat at the heart of the Industrial Revolution.1 At first, working a mule involved a variety of complex tasks. You needed to control the speed of the spindle, ensure the yarn was wound into the right shape, and periodically unwind the yarn properly; this made mule-spinning a relatively skilled job—at least at first.

In 1824 a Welshman named Richard Roberts invented the so-called self-acting mule. Far easier to use than existing mules, this set Roberts on a path to becoming one of the most celebrated engineers of the nineteenth century. Mill owners liked it too. In the words of Andrew Ure, a sort of nineteenth-century management theorist, “the effect of substituting the self-acting mule for the common mule is to discharge the greater part of the men spinners, and to retain adolescents and children” (Lazonick 1979). From Ure, this observation made it into Karl Marx’s Capital: “the instrument of labour,” Marx proclaimed, “strikes down the labourer.” The mule was a symbol of the dangers of technological progress: new technologies would make jobs fewer and worse and only the rich would benefit.

But this story didn’t turn out quite the way Marx expected. Far from being replaced by unskilled kids, adult mule-spinners prospered. The economic historian William Lazonick pointed out in 1979 that mule-spinners evolved into “minders,” taking on training, managerial, and supervisory roles in the mills. And the British textile trade expanded, creating more rather than fewer of these skilled jobs. Minders in Lancashire cotton mills enjoyed relatively high wages well into the twentieth century.

The moral of the tale of the mule-spinners is that more technology doesn’t necessarily equal fewer jobs or lower wages. The same lesson is suggested by the introduction of automated teller machines in banks. As James Bessen (2015) pointed out, the introduction of machines to dispense money actually saw a rise in the number of bank tellers in the United States. The reduction in branch costs and the increase in employees’ time available to talk to customers and sell financial products (having been freed from handing out cash) meant that banks opened more branches.

Indeed, stories that technology would spell the end of employment and lead to social crisis have been a mainstay of economic punditry for over a century. Louis Anslow, an enterprising journalist, collected an archive of news stories to this effect, with examples dating back as early as the 1920s, including a speech by Albert Einstein in 1931 blaming the Great Depression on machines, and the British Prime Minister James Callaghan asking Downing Street civil servants to review the threat to jobs from automation shortly before he was ousted by Margaret Thatcher.2

All this suggests that while technology has the potential to displace jobs and create inequality, it ain’t necessarily so.

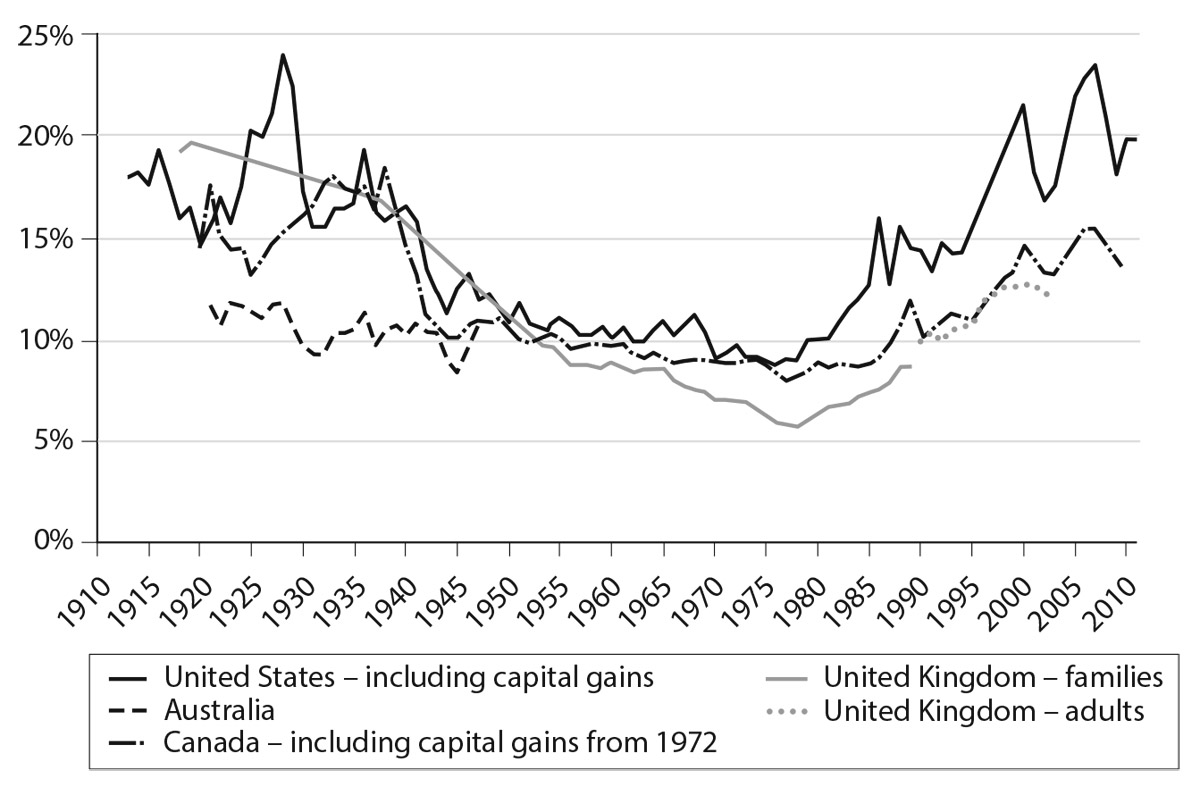

The second challenge to the mainstream explanations of inequality comes from Piketty’s observation that the rise in wage inequality is very concentrated at the very top. In the United States, the gap in income between skilled and unskilled workers, which initially gave rise to explanations based on skills-biased technical change, stopped diverging in about 2000. Since then, the big rises have accrued mostly to the top 1 percent. See figure 6.3.

It’s easy to imagine how low-skilled workers in developed countries might lose out if they don’t have the skills to work with computers, or if their jobs are threatened by lower-paid workers in other countries. But the way these changes would benefit only the very rich is less clear.

Some of the very rich have gotten richer because of technology or because they employ cheap foreign labor. But certainly not all. For every Silicon Valley mogul or quantitative hedge fund owner, there are a lot of senior managers of what we’d think of as normal businesses among the new elite. Piketty, for example, estimates that between 60 and 70 percent of the top 0.1 percent are chief executives and other senior corporate managers.

A third confounding fact is the role of housing in wealth inequality. Not long after the publication of Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century, the French economists Odran Bonnet, Pierre-Henri Bono, Guillaume Chapelle, and Etienne Wasmer noted that a big chunk of the growth in wealth inequality in both the United States and France was caused by the increase in value of residential property; Matthew Rognlie, an MIT graduate student who became known for his critique of Piketty, found the same (Bonnet et al. 2014; Rognlie 2015).

This suggests that to understand why wealth inequality is rising, we need to understand why housing wealth has risen so dramatically. This trend seems to have little to do with the rise of technology, of globalization, nor is it a feature of pure accumulation.

The last of the four phenomena, the differences in wages between firms, is a surprising source of income inequality. Economists have only recently begun to explore new and rich data sets combining both employer and employee data, and a recent study by Jae Song, Nicholas Bloom, David Price, Fatih Guvenen, and Till von Wachter (2015) looked at how earnings of workers in US firms changed between 1981 and 2013. Now, if the gap between managers and cleaners is rising, you might think that you would see a rising gap at all firms: the gap at an international legal firm rises and the gap at your local law firm rises. But it turns out this is not quite the case. Rather, leading firms are paying both their managers and their cleaners more relative to other firms: the gap between the occupations is still rising, but in addition the gap between these and the other firms is rising. Indeed, the authors found that “over two-thirds of the increase in earnings inequality from 1981 to 2013 can be accounted for by the rising variance of earnings between firms and only one-third by the rising variance within firms.” (They noted one exception to this: the fact that among the very largest firms, chief executives and other senior managers are being paid a lot more, in ways that seem correlated with their firms’ stock prices—a familiar finding.)

How Intangibles Affect Income, Wealth,

and Esteem Inequality

So it seems that neither new technology nor globalization nor simple accumulation fully explains the current levels and types of inequality we see in developed countries. Could the rise of intangible investment provide part of the answer? Let’s look at the possible ways in which an intangible economy might result in more of the kinds of inequality that people have been observing.

Intangibles, Firms, and Income Inequality

First of all, let’s consider the ways in which the rise of intangible investment could have driven the increase in income inequality that has arisen from differences between firms. As we have seen in chapter 4, some of the key characteristics of intangibles are scalability and spillovers. So in a world where intangible investment is very important, we would expect to see the best firms, firms that own valuable, scalable intangibles and that are good at exacting the spillovers from other businesses, being highly productive and profitable, and their competitors losing out.

As we saw in chapter 5, this is indeed the case. The rise in the spread between the top and bottom firms seems to be in industries with lots of intangibles. On the face of it this looks like a prime candidate for a rise in inequality. However, one has to be a bit careful. Just because a firm is profitable doesn’t mean it pays its cleaners more. After all, if they ask for a pay raise, the firm can potentially hire somebody else. So for a rising firm performance gap and rising wage inequality to be related, something in addition must be happening.

Who Is Benefiting from Intangible-Based Firm Inequality?

To get at this, let us ask: What sort of people are benefiting from the growing gap in firm performance?

One group is what we might call the “superstars”: people who are personally associated with very valuable intangibles that scale massively. This line of analysis was developed by the economist Sherwin Rosen (1981). In many cases the job of one person can be done by others, or a combination of others (so a fast hamburger-server’s job can be done by two slower ones). But in so-called superstar markets this is not true: the best opera singer or football player cannot be replaced by two not-quite-so-good ones. When technology, say broadcasting, raises the reach of such workers, their earnings can potentially rise very sharply. The intangible version of this story is that many superstars have privileged access to very valuable scalable intangibles that reap vast rewards: in some cases this is by outright ownership—for example, the tech billionaires who own significant equity stakes in companies they founded; in others, the superstar has special privileges to create more of a certain type of intangible—only J. K. Rowling can write new Harry Potter books, for example.

But, of course, most rich people are not stars or tech entrepreneurs; a significant proportion of the very rich are simply senior managers. What could account for this aspect of the rise in inequality?

It turns out the literature on interfirm inequality has some clues. The paper by Song and others that we discussed above used a clever technique to understand why the world seemed to be dividing into low-paying firms and high-paying ones. They looked at what happened to employee pay levels when they moved to firms that tended to be either high-payers or low-payers.

They were looking for evidence that low-paid people would tend to get significant pay rises when they joined high-paying firms. If true, this would suggest that what was really important was the firms themselves—that they were sitting on a money machine and were sharing out the proceeds among anyone lucky enough to land a job there (a phenomenon that will be familiar to anyone who has dealt with state-owned oil and gas companies in emerging countries). It turned out they didn’t find this. Instead, they found that the people joining high-paying companies tended to be highly paid already (a phenomenon they call “sorting”), and vice versa, and that this tendency got stronger between 1980 and 2008.

The Song study doesn’t tell us anything about the types of workers being hired by high-paying firms. But there is some evidence from a similar study by Christina Håkanson, Erik Lindqvist, and Jonas Vlachos (2015) looking at workers in Sweden. As (researcher) luck would have it, young Swedish men take standardized tests as part of their military service. These tests profile conscripts’ cognitive and noncognitive skills. Combined with the high-quality employee and employer data that Scandinavian governments produce, they are a gold mine for labor economists. Håkanson’s study showed that the workers moving to the high-paying firms were those who did well on their tests for cognitive and noncognitive skills.

What does this mean for inequality? It looks like those high-paying firms are possibly being more careful to sort and screen their workers. It seems to us that this sorting of workers is related to intangibles in two ways. First, it is a response to the importance of intangibles. Second, it is enabled by the rise of intangibles—or at least intangibles of a particular type. Let’s look at each of these in turn.

Sorting Workers: The Return of the Symbolic Analysts

You’ll recall from chapter 4 that one of the characteristics of intangibles is their contestedness. The right to use them and the ability to make the most of synergies between them are often up for grabs in a way that physical assets aren’t. This characteristic makes particular kinds of employees especially valuable to a firm that wants to make the most of its valuable intangibles.

To illustrate this, let’s take a step back in time to the turn of the twentieth century. Around 1900, it turns out that about a quarter of late-Victorian British companies hired a lord or a member of parliament (MP) to sit on their board of directors. Now, because British company archives are thorough, historians have been able to look in some detail at who these elite directors were and what good they did for the companies that hired them. The economic historians Fabio Braggion and Lyndon Moore (2013) looked at the records of 467 listed companies in the decade around 1900 to understand the benefits of having a politically and socially connected director. It turns out that for most companies, there was no measurable advantage to elite board members—companies that had them did about as well, on average, as companies that didn’t, in terms of share price growth, financing, fundraising, and other measures of performance.

But there was one group of companies for which having MPs or lords on the board brought a measurable advantage: companies working in the emerging technology sectors of their day: synthetic chemicals, car and bike manufacturing, electricity generation and distribution, and so forth. Braggion and Moore showed that new tech companies with grand directors saw increases in their share price, including specific jumps if an existing director was elected to Parliament. They also found it easier to raise financing.

It seems that in industries with lots of uncertainty, involving new technologies, new markets, and unclear ownership rights, these well-connected directors helped smooth over some of the problems we’ve seen that affect intangible investments: uncertainty of ownership, difficulty of valuation, and the need for good relations with a wide range of potential partners.

An MP could help make sure the company got the benefits of its investments (for example, using influence to make sure a patent was honored), and their presence acted as a signal to investors that the company was well positioned to enforce its rights.

The MPs who secured board positions on new tech companies were useful not because they were tech experts, but because new technology businesses often depend on intangibles (from R&D to the organizational and branding investments needed to bring new products to market). These intangibles generate contestable uncertainty (Can the patent be defended? Will our distribution rights be honored?), and having big shots on the board both helped manage these uncertainties and gave investors confidence that they would be managed.

Braggion and Moore’s Victorian grandees have their modern equivalents. Back in the early nineties, when intangible investment was growing but before it had come to dominate tangible investment, economists were beginning to notice changes in the economy.

Future US Treasury Secretary Robert Reich predicted that power in the workforce of the future would be in the hands of what he called “symbolic analysts”: product managers, lawyers, business development people, design engineers, marketers, head-hunters, and so forth. Like the Swedish workers who benefited from higher salaries in Håkanson’s study, symbolic analysts are educated, smart people with a combination of noncognitive skills (because managing spillovers often involves social interaction) and cognitive skills (because intangibles are usually knowledge assets).

It also seems to reflect what we see when we survey companies in particular sectors. A qualitative study by the innovation foundation Nesta of companies that made intensive use of data and analytics showed that these companies are particularly eager to hire people who combine decent data analytical skills with the soft skills needed to broker relationships inside and outside their own company (Bakhshi, Mateos-Garcia, and Whitby 2014).

This provides a striking link between the rise of intangibles and increasing income inequality. Intangible investment increases. Because of its scalability and the benefits to companies that can appropriate intangible spillovers, leading companies pull ahead of laggards in terms of productivity, especially in the more intangible-intensive industries. The employees of these highly productive companies benefit from higher wages. Because intangibles are contestable, companies are especially eager to hire people who are good at contesting them—appropriating spillovers from other firms or identifying and maximizing synergies. These are Reich’s symbolic analysts, Braggion and Moore’s influential elites, or Håkanson’s talented conscripts: people who are already doing well and, in a world of increasingly important, scalable intangibles, are likely to do even better.

Sorting Workers: Intangibles and Worker Screening

The second way that intangibles encourage income inequality is by helping hierarchies emerge both between and within firms.

Research by the economists Luis Garicano and Thomas Hubbard (2007) looked at the pay of American lawyers between 1977 and 1992. They found that the pay of the highest-earning lawyers increased dramatically over the period (a trend that seems to have continued in the two decades since). What was particularly interesting was the reason their pay had increased. They were being paid more because they were working with greater numbers of associates (junior lawyers), or, in the paper’s words, because the “coordination cost of hierarchical production” decreased. The best lawyers invested in new ways of dividing up work so that they could improve what they call their “leverage”—their ability to focus on the most complex and remunerative tasks.

This kind of trend is a result of investment in intangibles, in particular organizational development, software, and to some extent service design. It involves designing new ways of working, developing hierarchies within firms, and putting in place software and systems to manage them.

We can see something similar going on in the field of management consulting. We saw in chapter 4 how consulting firms in the 1950s and 60s came up with organizational innovation that allowed them to staff projects with a junior staff, leavened with a small number of high-paid partners. Later in the twentieth century, further organizational innovations caused the business of management consulting to segment further. In the 1980s it would be typical for a McKinsey project to begin with a few weeks of data gathering—understanding market sizes and shares, learning about customers, and so forth—before the strategic advice began. As a result, projects were longer. By the 2000s much of this market-sizing work had been outsourced to specialized market-intelligence firms, which would prepare detailed reports and projections on dozens of industries and sectors, which would be sold to consultants and bankers for a fixed fee. Consulting firms invested in knowledge management departments to order and curate these reports. The market for these market-intelligence reports was pretty competitive, and quickly they became far cheaper than the customized market sizings carried out by consulting staff (Bower 1979).

In the management consulting industry, the kind of institutional innovation described by Garicano and Hubbard led to inequality among firms, with the industry separating into companies providing higher- and lower-cost services and employing different types of staff—exactly the kind of division that Song and others observed in the United States.

Intangible Myths

The effects of growing intangible investment on income inequality that we have looked at so far have been in a sense rational. They show particular workers being paid more either because they are intrinsically worth more to their employers in an intangible-intensive economy, or because an intangible economy encourages a division of labor that has made them more useful to their employers than others.

But there may also be irrational factors at play. As Song and others pointed out, along with the rise in inequality between firms, there has been a big increase in inequality at the largest firms between the highest-paid employees, especially CEOs, and everyone else. The correlation between high CEO compensation and company performance seems weak. So what is going on?

One possibility is that in a world in which abundant intangibles are increasing uncertainty, and where talented employees are able to some extent to help firms make the best of this uncertainty, it becomes easier to create a cult of talent that can be exploited by people at the top of firms to demand higher pay.

As the economic journalist Chris Dillow3 likes to point out, humans are particularly prone to what psychologists call “fundamental attribution error”—the mistaken assumption that outcomes (such as how well a company does) are related to salient inputs (such as the skill of the CEO) rather than dumb luck or complex, hard-to-observe factors. A world in which increased intangible investment makes skilled managers a bit more important could easily lend fuel to the fire of fundamental attribution error, providing a rationale for powerful people like CEOs to increase their pay by more than the economic fundamentals of the change would justify.

A final possibility is that shareholders are being insufficiently attentive to the pay of CEOs, thereby allowing it to rise. Brian Bell and John Van Reenen (2013) have some interesting evidence here, showing that CEO pay is more correlated with performance the more share ownership is concentrated (in their sample, in institutional investors). Perhaps dispersed shareholders have less incentive to monitor CEO pay, a matter we return to in chapter 8.

Housing Prices, Cities, Intangibles, and Wealth Inequality

One of the many achievements of Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century was to remind pundits and policymakers that inequality was not just about income, but also about wealth.

It seems to us that the rise of the intangible economy can help explain the long-term rise of inequality of wealth as well as inequality of income. There are two main ways this is happening. First of all, intangibles have helped drive the increase in property prices, which explains a significant chunk of the increase in wealth of the world’s richest people. Second, the fact that intangible capital tends to be geographically mobile has made it harder to redistribute wealth via taxation in the way that governments of the 1950s, 60s, and 70s did.

Let’s consider property prices, first of all. Of course, a house or an apartment is quintessentially tangible. Real estate originally got its name because it is immobile; it’s real-ly there. But in fact, the value of property, especially the kinds of property that have risen most dramatically in value over the last thirty years, derives to a great extent from intangibles.

As we discussed earlier, a number of commentators on Piketty’s work have pointed out that a significant proportion of the increase in wealth of the richest people in the United States (and almost all of the extra wealth of France’s richest) stems from the rising value of their property. As Rognlie (2015) pointed out, this does not seem to be because they are buying more properties; it is because the houses and apartments they own have steadily and powerfully risen in value over the last three decades.

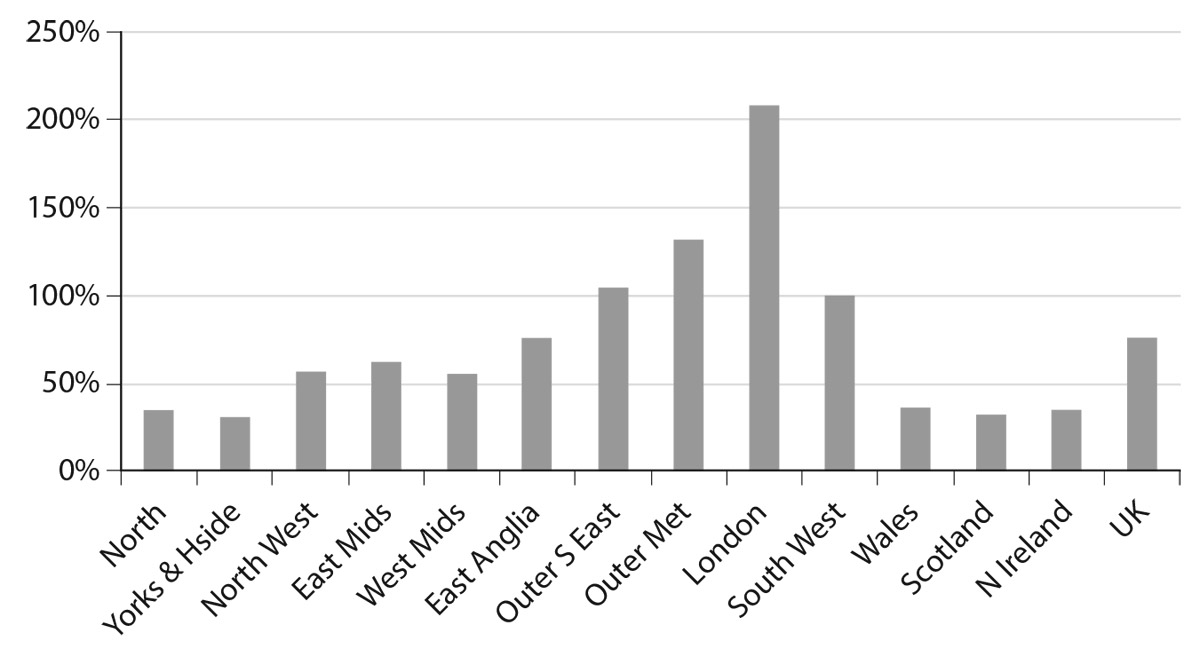

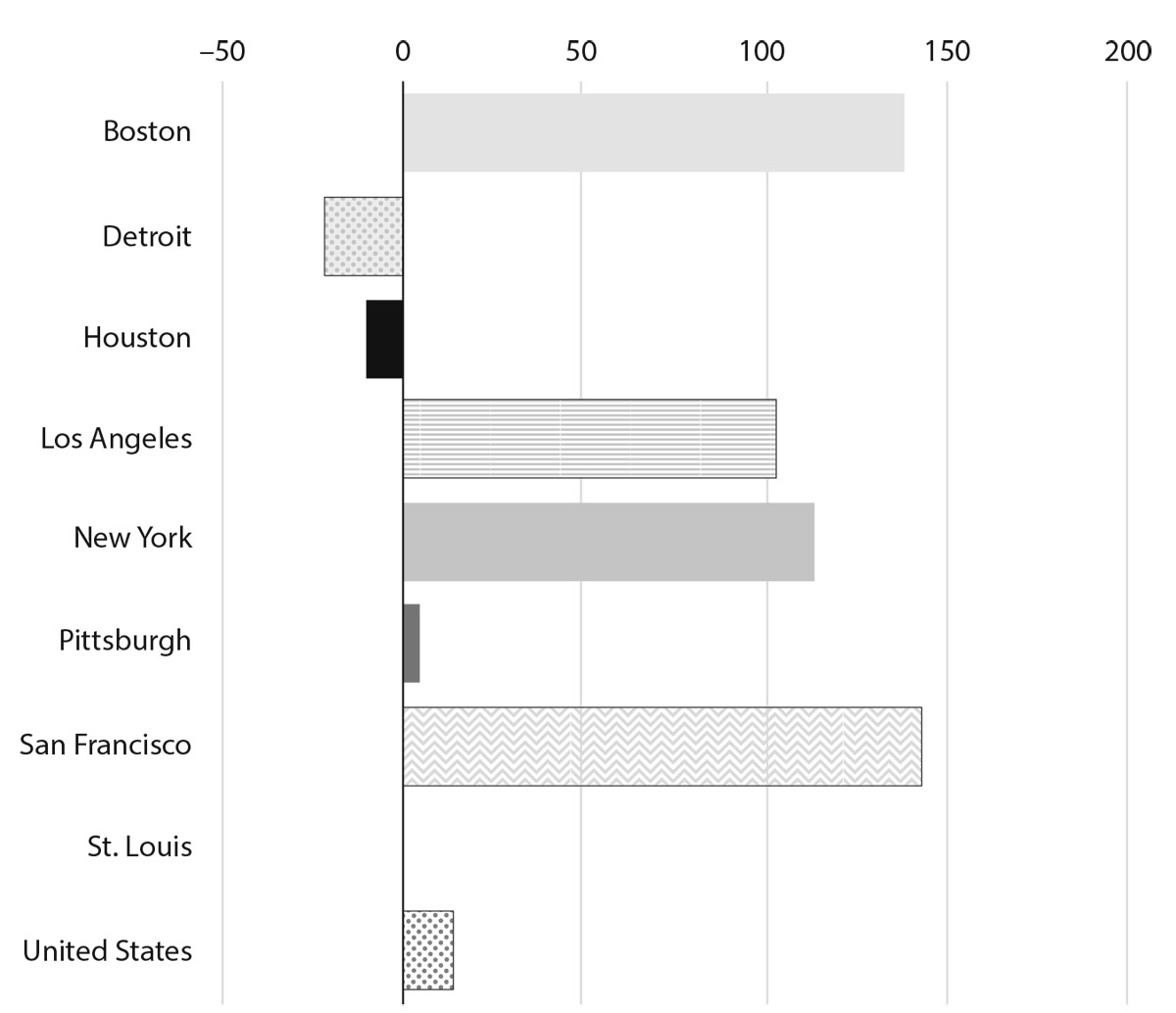

Now, house price inflation is not evenly distributed. As figure 6.4 for some US cities and figure 6.5 for UK regions show, the price of housing has more than doubled in real terms in some places and stayed more or less the same in others.

The cities where housing prices have risen dramatically tend to be the ones with thriving economies, where it is hard to build new dwellings. But this explanation only raises a further question: Why are the economies of some of these cities thriving?

Here we can turn to the work of the economist Edward Glaeser, whose influential research has focused on how economic growth happens in cities (see, for example, Glaeser 2011). It had long been known that cities are rich in spillovers. Dense populations mean people exchange, observe, and copy ideas from one another. Initially, economists had focused on spillovers within industries; the Marshall-Arrow-Romer spillovers we referred to in chapter 4. Glaeser’s research highlighted the importance of a different effect: positive spillovers between industries. Indeed, he argued that for thriving US cities like New York these types of spillovers, where ideas or opportunities from one sector are exacted into another, were more important. Glaeser’s example was the invention of the bra, which was developed not by lingerie makers but by dressmakers (Glaeser 2011; Glaeser et al. 1992).

Indeed, cities that relied on single industries, like Youngstown, Ohio, which made steel, or Akron, which made tires, or most famously Detroit, the motor city, tended to do less well in the modern age than cities with a range of industries. Glaeser called these “Jacobs spillovers,” in honor of Jane Jacobs, the urbanist and defender of messy, unplanned cities.

It seems that this effect is still going strong. A recent paper by Chris Forman, Avi Goldfarb, and Shane Greenstein (2016) showed not only that the San Francisco Bay Area has become an increasingly important location of invention in the last few decades, but also that it has become a source of inventions in many diverse areas, not just software and semiconductors. In fact, it is an important originator of patents not mentioning IT at all.

Glaeser’s model of urban spillovers fits neatly with the characteristics of intangibles we described in chapter 4. Cities provide an opportunity to profit both from spillovers (that is to say, benefiting from intangible investments made by other firms) and synergies (combining different intangibles to produce unexpectedly large benefits). Viewed in this light, the link between the so-called creative class and cities is not surprising.

In a world where intangibles are becoming more abundant and a more important part of the way businesses create value, the benefits to exploiting spillovers and synergies increase. And as these benefits increase, we would expect businesses and their employees to want to locate in diverse, growing cities where synergies and spillovers abound. One possible result of this would be to encourage people to build more houses and offices in big cities. But, of course, in most cities there are big regulatory barriers to building, from zoning rules to legal action by NIMBYs. So instead, the price of housing rises, and the wealthy, who are more likely to own this kind of prime real estate, get wealthier, as Piketty described.

Taxes, Mobile Intangibles, and Wealth Inequality

It also seems that the growing importance of intangibles is contributing to another element of Piketty’s story of rising wealth inequality, specifically, the apparent unwillingness of governments to tax capital in the way they once did. Piketty argues that redistributive taxation (together with higher inflation rates) helped erode the accumulated wealth of the rich in the postwar decades, but that governments have lost the nerve for this kind of taxation since 1980.

It is certainly true that there have been major ideological shifts in how willing governments are to redistribute wealth through taxation. But perhaps the rise of intangibles has also played a role.

In countries like the United States and the UK, capital gains have since the 1990s been taxed at a lower rate than income. This is a political sticking point, not least because it is mainly rich people who have capital gains because they are much more likely to own capital. The reason for this lower rate of taxation is that capital is mobile, and so taxing it will, according to a large body of economic research, encourage its owners to shift their capital to a lower tax jurisdiction. The same can’t be said, or at least not to the same extent, for income from employment, since most people’s jobs take place in a particular location and are much harder to move. So, although it might seem fairer, from the point of view of redistribution, to tax capital income more than employment income (as governments in the 1950s and 1960s did, with their separate tax rates for “unearned income” and the like), most governments have concluded it is not possible: capital is just too flighty.4

Now consider the effect of the rise of intangibles. Nowadays, the average firm invests far more in intangibles than its equivalent back in the 1990s. And intangible assets are, on the whole, more geographically mobile than tangible assets. For an oil company to move its physical refining operations from the UK to the Netherlands would be a massive undertaking, a decade-long project of the kind most firms would undertake only if absolutely necessary. But if Starbucks wants to move the ownership of their brand or the IP behind their UK store operations to the Netherlands or Ireland or Luxembourg, it can be done with some modest legal work.

This intensifies what policymakers call “tax competition”: the idea that businesses and owners of capital will shop around for the most favorable tax policies. This makes it harder for governments to increase taxes and exacerbates the problem that led to lower taxes on capital in the first place.

Let’s summarize. The rise of intangible investment helps explain wealth inequality in two ways. Because businesses flock to cities to exploit the spillovers and synergies associated with intangibles, it is a major cause of the rise in the value of prime urban property, which accounts for much of the new wealth of the very rich. And because it is unusually internationally mobile, intangibles increase tax competition, which makes it harder for governments to reduce inequality by taxing capital more.

Openness, the Left-Behind, Intangibles,

and Esteem Inequality

At the beginning of this chapter, we mentioned a type of inequality that is as much social and attitudinal as it is economic. This is the inequality of esteem that is increasingly prevalent in society in the United States, the UK, and elsewhere in Europe—that is, the growing sense that the population is dividing into two halves: one more cosmopolitan, more educated, and more liberal and the other more traditionalist, and more skeptical of elite opinion and of metropolitan values.

It’s a divide that has made itself felt dramatically in politics. Supporters of Donald Trump, of Brexit, and of many of Europe’s growing populist parties share a sense of being alienated from and patronized by the dominant elites in their country who do not share their values.

One might expect that these groups are alienated because they are poor. But the evidence of the UK’s referendum on leaving the EU suggests there may be more to it than this.

Political scientist Eric Kaufmann pointed out that it’s not class and wealth that predict whether someone will vote to leave the EU, but rather social conservatism and attitudes toward authoritarianism. In Kaufmann’s words, “culture and personality, not material circumstances, separate Leave and Remain voters. This is not a class conflict so much as a values divide that cuts across lines of age, income, education and even party.” Kaufmann suggested that Leave voters tended not only to want to leave but also to hold other socially conservative views, for example, to be in favor of corporal punishment: polling conducted by Lord Ashcroft supported this conclusion (Kaufman 2016a; Kaufman 2016b).

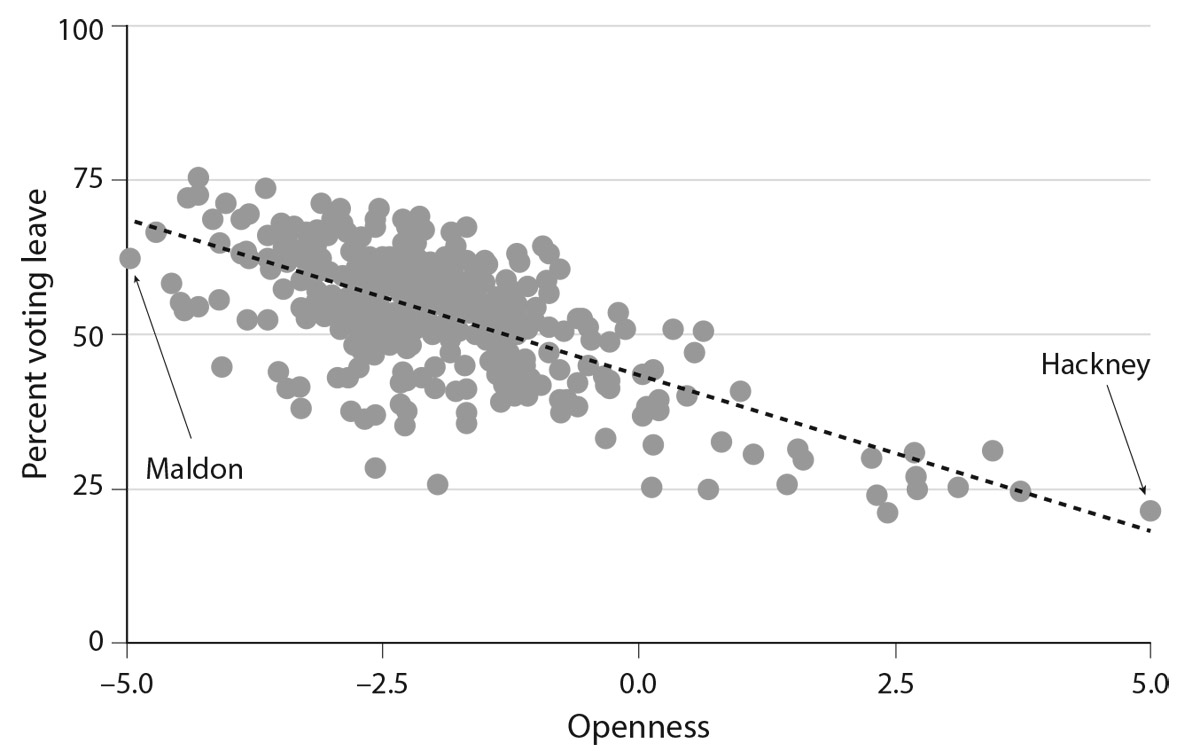

The psychologist Bastian Jaeger5 explored this by looking at the correlation between areas that voted to Remain in the EU and psychological traits. Psychologists have settled on five psychological traits that they believe capture dimensions of human personality. Jaeger looked at the trait of “Openness to Experience,” which is associated with cosmopolitanism and an interest in the new. As figure 6.6 shows, people who are open to new experiences seemed to vote Remain, and those who are more traditionalist tended to vote Leave, regardless of income or class.

Now, let’s consider the kinds of people who might benefit from an economy in which intangibles are more abundant and important. We know that in an intangible economy, the ability to appropriate spillovers and make the most of synergies is prized. Research by psychologists suggests that people who are more open to experience are better at this. Perhaps this is because they are better at making the kind of connections between different ideas and people that, as Edward Glaeser and Jane Jacobs pointed out, are so important to the economic magic that goes on in cities. Perhaps creativity and innovation require openness to ideas (there is evidence that openness to experience helps in innovative and creative jobs).

This suggests a new explanation for why the divide between supporters of Trump, Brexit, and similar movements and their respective nonsupporters is growing. The supporters tend to share certain underlying attitudes such as traditionalism and low openness to experience. But they find themselves in an economy that, because of the growing importance of intangibles, is increasingly favoring people with different psychological traits and value systems. The cultural causes of Brexit and Trump are exacerbated by the economic causes—causes that arise from the emergence of an intangible economy.

Conclusion: The Implications of an Intangible Economy for Inequality

We’ve argued that the rise of intangibles explains several aspects of the long-run rise in inequality.

First, inequality of income. The synergies and spillovers that intangibles create increase inequality between competing companies, and this inequality leads to increasing differences in employee pay (recent research suggests these interfirm differences account for a large proportion of the rise of income inequality). In addition, managing intangibles requires particular skills and education, and people with these skills (such as Reich’s symbolic analysts) are clustering in high-paid jobs in intangible-intensive firms. Finally, the growing economic importance of the kind of people who manage intangibles helps foster myths that can be used to justify excessive pay, especially for top managers

Second, inequality of wealth. Thriving cities are places where spillovers and synergies abound. The rise of intangibles makes cities increasingly attractive places to be, driving up the prices of prime property. This type of inflation has been shown to be one of the major causes of the increase in the wealth of the richest. In addition, intangibles are often mobile; they can be shifted across firms and borders. This makes capital more mobile, which makes it harder to tax. Since capital is disproportionately owned by the rich, this makes redistributive taxation to reduce wealth inequality harder.

Finally, inequality of esteem. There is some evidence that supporters of populist movements (Brexit in the UK, Trump in the United States) are more likely to hold traditionalist views and to score low on tests for the psychological trait of openness to experience. Openness to experience seems to be important for the kind of symbolic-analysis jobs that proliferate as intangibles become more common. So the increasing importance of intangibles leads to economic pressures that underscore the political divides driving today’s populist movements.