QUARTER SESSIONS

Justices of the Peace met together regularly at Quarter Sessions, four times each year, in the weeks after Epiphany, Easter, Midsummer and Michaelmas.1 Some Benches met regularly in the same county town; others itinerated. A few held separate Sessions for different parts of their county; for example, the Sessions for West Kent was held at Maidstone, for East Kent at Canterbury. There were separate Commissions for the Yorkshire Ridings, and for the Parts of Lincolnshire.

Some towns had separate Quarter Sessions. Exeter, Bristol and London were counties in their own right. Many smaller boroughs, such as Great Torrington (Devon), and Guildford (Surrey), also held their own Quarter Sessions, outside of the jurisdiction of the county Bench. Haverfordwest (Pembrokeshire) even had its own Lord Lieutenant. The activities of borough Quarter Sessions are not within the scope of this book.

Quarter Sessions presided over counties, varying in size from Rutland, of 147 square miles, to Devon, 2,590 square miles. Many had detached portions; for example, Furness lay in Lancashire, although bounded by the sea and by Westmorland. County boundaries were amongst the most enduring features of English local government.

The tasks dealt with by Quarter Sessions were many and varied. The growth in its powers were outlined in Chapter 3. It exercised judicial, executive, and even some legislative powers: Justices had no concept of the separation of powers. However, the court only acted on judicial process, even for administrative purposes: there had to be presentment and indictment before money could be spent on bridges. Occasionally, Quarter Session orders amounted to legislation. They could prohibit the keeping of fairs and revels, disqualify publicans from serving as constables, restrict the issue of badgers’ licences, adapt the Poor Law as they saw fit (as the Berkshire magistrates notoriously did at Speenhamland), or even ban paupers from keeping dogs.

Exeter Castle. Quarter Sessions and Assizes were held here, and prisoners were incarcerated.

Despite these powers, the Bench was frequently ineffective. In 1387, Oxfordshire Justices attempted to secure the appearance of twenty-six felons; only six were actually tried and convicted.2 In 1596, it was estimated that only one felon in five was successfully brought to book.3 In the mid-eighteenth century, Sir John Fielding argued that ‘not one in a Hundred of these robbers are taken in the fact’.4

It did not help that the concept of order held by the gentry was not always accepted by the lower orders. Quarter Sessions orders prohibiting wakes and revels were frequently issued, but almost as frequently ignored. The West Riding Justices’ attempt to ban cock-fighting in the 1650s predictably failed.5 The tithingman sent to disperse a banned revel at Langford Budville (Somerset) in 1656 was attacked by men engaged in cudgelling.6

The authorities could be even more ineffective when more substantial issues were at stake. When the Crown wished to disafforest royal hunting parks such as Selwood (Wiltshire) and Gillingham (Dorset), neither Justices of the Peace, Sheriffs nor even Deputy Lieutenants, could control the opposition of aggrieved tenants and poor cottagers.

During the Civil War, Sessions sometimes could not even be held. In Wiltshire, the Justices did not meet for two years after the Trinity 1644 Sessions.7 When meetings resumed, they had to deal with offices vacant, funds misappropriated, taxes unpaid, records lost, routine interrupted, vagrants unrestrained, the poor unrelieved, bridges damaged and roads neglected. The records reflect Parliament’s victory. Where pre-war records referred to ‘Jurors for the Lord the King’, Interregnum records referred to ‘Jurors for the Keepers of the Liberties of England’, and, subsequently, ‘Jurors for the Lord Protector of the Commonwealth’. Even more noticeable was the substitution of English for Latin. During and after the war, security was a prominent issue. Interregnum Justices watched the movements of Royalists closely. After the Restoration, the activities of former Parliamentarians demanded equally close attention. Justices undertook searches for arms, and interrogated anyone suspected of plotting for the wrong side.

Sessions were summoned by a precept addressed to the Sheriff from two Justices of the Peace, or from the Clerk of the Peace, notifying him of the date and place of meeting. The Sheriff proclaimed the Sessions, summoning High Constables, those wishing to make complaints and jurors for both the grand and petty juries. He attended himself, with his under-Sheriffs and bailiffs. Hundred Bailiffs summoned sufficient men to form local juries of inquiry. Jury panels in late sixteenth century Staffordshire could number as many as 100, although numbers were declining.8

JURIES

The statutory qualification for jury service from 1595 was ownership of lands valued at 80s per annum. This was increased to £10 in 1692. From 1601, Sheriffs were supposed to compile full listings of qualified freeholders; in 1606, responsibility for this task was transferred to Justices of the Peace. Two copies were produced, one for the Sheriff, the other for the Clerk of Assize. From 1696, constables prepared lists of those qualified to serve for the Michaelmas Quarter Sessions; these were copied by Clerks of the Peace into special freeholders’ books. Another book was required by an Act of 1730; Sheriffs had to record the services of each man, and post lists of those eligible for service in parish churches. The County Juries Act of 1825 altered procedures: the lists had to be compiled by constables and churchwardens, delivered to Petty Sessions each September, and taken to Michaelmas Quarter Sessions by High Constables. The Clerk of the Peace used these lists to compile duplicate freeholders’ books, one of which he kept; the other was passed to the Sheriff for use as the Jurors’ book for the forthcoming year.

Under the Tudors and Stuarts, finding sufficient jurors was difficult. Nevertheless, the composition of Grand Juries was carefully controlled, indicating the importance attached to their functions. In the eighteenth century, recruitment became easier: service conferred social status. Jury lists and freeholders’ books provide comprehensive annual directories of gentry, substantial yeomen and prosperous tradesmen.9 In more recent centuries, many were printed, sometimes giving addresses and occupations as well as names.

A number of different juries had to be summoned. The Grand Jury was chosen from ‘the most sufficient freeholders’, and frequently consisted of High Constables. Jurors served repeatedly (at least in Cheshire), and were considered to be ‘better acquainted with the common grievance of the Countrie, then Justices are’.10 They determined whether indictments were ‘true bills’ to be tried before the Justices. Their own presentments gradually ceased to have much to do with criminal matters, concentrating on such matters as bad roads, collapsed bridges, disorderly alehouses, excessive vagrancy and corrupt or inefficient officials. They petitioned the Crown on such matters as Ship Money and (in 1642) the control of the Militia. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, they were increasingly consulted before new legislation was considered by Parliament. The Grand Jury acted as the voice of the county, although it had its most decisive role at Assizes (see Chapter 12).

Freeholders liable to serve as Jurymen, from a Wiltshire Freeholders Book. (Wiltshire & Swindon History Centre A1/265/8.)

Juries of Hundreds and liberties had tasks similar to those of the Grand Jury, for their area. In 1719 Essex jurors were instructed to present the state of roads and bridges, the abuses of alehouse keepers, and the depredations of poachers.11 Hundred juries gradually became obsolete, their role in presentment taken over by constables. In Wiltshire, they ceased to be empanelled in 1782.12 Petty juries, consisting of twelve men, heard the actual trials of criminal cases and pronounced verdicts. The distinction between grand and petty juries was not always clear; in late sixteenth-century Staffordshire both seem to have acted as the jury of accusation.13

PROCEDURE

Quarter Sessions procedures evolved over the centuries. For example, presentments and indictments were originally identical, and differentiation between them took centuries to develop. The Grand Jury emerged by the seventeenth century from a variety of juries of inquiry. There was ‘little method or arrangement of business’14 until the eighteenth century, when concern to enhance the ‘majesty’ of proceedings, combining with the need for greater efficiency, led to the rationalisation of procedures. Only a rough guide to what actually took place can be given here.15

Sessions began with a sermon. The Justices were then escorted to the court by the Under-Sheriff and bailiffs. The Crier proclaimed the Sessions, the Clerk of the Peace read the Commission, and the Sheriff returned his precept, with the nomina ministrorum.16 The crier called over the names of those required to be present, recording absences. Reasons for absence, such as illness or death, were noted, as were fines imposed on defaulters. Even absent Justices could be fined. Fines were recorded in estreats.

Justices of the Peace then put in their examinations, with their recognizances requiring the appearance of defendants in court. Coroners handed in their inquests and Hundred Bailiffs handed their lists of potential jurymen to the Sheriff. He selected the petty juries, subject to Justices’ approval. If insufficient jurors appeared, freeholders present in court could be called. Juries were sworn, and the charge was delivered.

A nineteenth-century jury.

The charge instructed the Grand Jury – and sometimes inexperienced Justices – in their duties. In 1580, the Wiltshire jurors were told that they were to inquire into three matters: whether ‘God be truely honoured’, whether ‘Her Majestie was truly obeyed’, and whether ‘Her Majesties subjects be in peace’.17 After the Restoration, Sir Peter Leicester’s charges provided ‘essentially elegant homilies on the nature of English law’, directed at the many young and inexperienced Justices who sat on the post-Restoration Bench.18 Charges could be heavily political. In the 1640s, many justified taking up arms against the Crown. The Restoration saw many lectures on the iniquities of republicanism. In the early 1700s, charges frequently debated the validity of Tory and Whig principles. A century later, they sometimes argued the case for reform.

The charge was the responsibility of the chairman, who acted as the deputy of the Custos Rotulorum. Frequently, the most senior Justice present served. In addition to presenting the charge, the chairman kept order during proceedings, ruled on points of law and pronounced sentence. He was, however, merely primus inter pares amongst the Bench. By the early eighteenth century, chairmen were being elected; the West Riding Quarter Sessions resolved to elect one in 1709.19 Increasingly, the chairmanship was held for longer periods than just a single session, allowing chairmen to exercise supervision between sessions. In the nineteenth century, separate chairmen for civil and criminal matters began to be appointed.

During the reading of the charge, the Clerk of the Peace wrote out the names of the several juries, for the information of jury foremen. The court then received sacrament certificates, oaths of allegiance and declarations against transubstantiation. The crier then called for indictments from prosecutors, and the Grand Jury withdrew to consider them, together with the presentments, informations and petitions it had received. In the thirteenth century, presentment and indictment were interchangeable terms. However, by the sixteenth century, the two terms referred to documents which could be quite different.

Indictments were written on parchment (in Latin until 1733), and were usually based on gaol calendars. In Caernarvonshire, they commenced ‘Inquiratur pro domino rege si…’: ‘Let inquiry be made for the Lord the King …’.20 They gave the name, parish and occupation of the accused, the year, date and place of the offence, the name of the victim if appropriate, the value of any goods stolen, and the supposed intention of the accused. They might be endorsed with further information as cases proceeded. The foreman of the Grand Jury endorsed them as either billa vera (a true bill), or ignoramus, which ended the matter (unless further evidence subsequently appeared). Indictments merely provided a statement of prosecution cases, based upon Justices’ preliminary examinations, so it is not surprising that ignoramus verdicts were frequent. Magistrates’ examinations developed a more thoroughly judicial character in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and consequently Grand Jury deliberations gradually lost their purpose. That process continued as the police took over the task of prosecution. The Grand Jury was moribund for almost a century, and finally abolished in 1948.

The court also proceeded by means of presentment. Presentments, like indictments, were endorsed billa vera or ignoramus, and sometimes initiated criminal prosecutions. Many concerned administrative matters. They could be made by High Constables, Hundred juries, the Grand Jury and individual Justices. Sometimes, constables and jurors subscribed the same presentment. High Constables made presentments on the state of their Hundreds, reporting such matters as recusants, the keeping of disorderly houses, and the harbouring of vagrants. They also passed on the presentments of parish constables. These were frequently responses to questionnaires issued by Assize judges, and included many matters not likely to be prosecuted by private individuals. A reconstructed questionnaire from Worcestershire is in the box below. The resultant presentments provided much useful information for Quarter Sessions to proceed upon, and also for researchers to analyse.

Questions probably posed to Worcestershire Constables, c.1635

1. What taverners, vintners selling wine, and cooks are there in the parish?

2. At what rate do bakers sell bread?

3. Who keeps ordinaries or victualing tables in their houses?

4. What rates are charged at inns for men and for servants?

5. Are any unlawful games practised in taverns or victualing houses?

6. What price is charged by innkeepers for horses and their food?

7. Who sell ale; are they licensed or unlicensed?

8. Is any tobacco grown?

9. Do any lodge rogues, vagabonds, or suspected persons?

10. Are watch and ward duly kept: are rogues found wandering?

11. Are the highways and bridges in good repair?

12. Are there any recusants, seminaries or Jesuits in the parish?

13. Are there any inordinate tipplers or drunkards, common swearers, or other idle and disorderly persons in the parish?

High constables could present parish constables who defaulted on their obligations. In the eighteenth century, however, there was an increasing tendency for constables to neglect presentments and to simply report omne bene – all well. The practice of presentment by High Constables and Hundred juries gradually became moribund, and was abolished in 1827.

Grand Jury presentments frequently concerned more general matters. In late-Elizabethan Norfolk, they probably played an important role in attacking patentees.21 At the outbreak of the Civil War, Grand Juries helped to determine which side the county supported. In 1640, the Worcestershire Grand Jury petitioned Parliament against the powers of the Council of Wales and the Marches.22 More routinely, the Wiltshire Grand Jury in 1677 requested the Bench to order that a certificate of conformity be produced before alehouse licences, were granted.23 In 1679, Charles II sought the support of Grand Juries for his actions during the Exclusion crisis. Eighteenth-century Grand Juries were frequently packed by the Sheriff with his supporters, and used for party political purposes.

Presentments made by Justices of the Peace usually concerned some public nuisance. The state of the roads attracted increasing attention in the eighteenth century. So did bridges, gaols and parish workhouses. By the early nineteenth century, Justice’s presentments had become a standard method of initiating administrative action: Clerks of the Peace made out presentments, seeking Justices prepared to sign them and implement action.

Whilst the Grand Jury was deliberating, the Justices spent time dealing with routine administration. Statutes were proclaimed; statutory appointments were made; county rates, wages, and the prices of ale and soap were fixed. Then, dinner was served.

After dinner, trials commenced. Many accused were bailed rather than gaoled before trial. Those who failed to appear were summoned by ‘process’. Failure to answer a writ of venire facias could lead to various further writs, and culminate in an exigi facias, or writ of outlawry. The outlaw could be killed on sight, and have all their goods seized. Despite these provisions, however, attendance in court was difficult to enforce. In seventeenth-century Surrey, hundreds of writs were issued to compel attendance; the same names appeared repeatedly.24

The gaoler brought in his prisoners, and trials on indictments marked billa vera proceeded, or were referred to Assizes. Pleas might be noted on indictments: cogn (cognovit) for a guilty plea, or po se (ponet se) if the accused asked to be tried by jury. If he refused to plea, stat mute or nichil dicit was noted. Occasionally, cases were postponed, and the prisoner returned to gaol until the next Sessions. If the indictment was endorsed ignoramus, or a prosecutor failed to appear, the accused would be discharged at the end of the Session.

It was up to victims to lay information before a Justice, to gather evidence, to make sure that witnesses attended, and to prosecute. Examining magistrates did not necessarily attend court, although they did send in their examinations. Many victims were, unsurprisingly, unwilling to prosecute, especially as they had to pay their own costs.25 Many cases went unreported or unsolved; in 1596, it was suggested that perhaps 80 per cent of offenders escaped justice.26

Victims’ reluctance to prosecute increasingly led the authorities to offer rewards for the successful apprehension and prosecution of felons. An Act of 1692 offered a £40 reward for the apprehension and conviction of highwaymen; the ‘Tyburn ticket’, created under an Act of 1699, offered exemption from parish office to all those who successfully prosecuted a felon. From 1752, judges could order costs to be paid to successful prosecutors. Subsequent legislation, culminating in the Criminal Justice Act of 1826, provided expenses to witnesses as well as prosecutors. In 1785, the Surrey Bench initiated a fund to reward successful prosecutions of felons.27 In the eighteenth century, a steadily increasing number of associations for the prosecution of criminals were founded. These were mutual aid societies which enabled many to initiate prosecutions who would not otherwise have done so. From 1818, costs were met by the county, and from c.1850, the new police forces increasingly took over the task of prosecution.

The court heard a number of cases – perhaps as many as a dozen – at the same time. Once sufficient prisoners had been arraigned, the Sheriff returned a petty jury, the cases were heard, and juries delivered their verdicts, which required unanimity from the fifteenth century onwards. Each case took only a few minutes; juries frequently did not leave the courtroom to deliberate. Defence lawyers were not permitted. It was not until the early eighteenth century that cases began to be considered separately, and not until the nineteenth century that the confrontation between accuser and accused became a confrontation between prosecuting lawyer and defence lawyer.

Trials were followed by the hearing of traverses. These were defences against accusations of misdemeanours (see below) which had been adjourned from the previous Sessions to allow defendants to prepare their traverse, that is, their defence. Many concerned administrative matters such as liability for bridge repairs. Each case required a separate jury, and both sides could retain attorneys. Judgement frequently turned on complex issues of ancient rights and liberties.

Traverses were followed by the hearing of grievances, before the Grand Jury was discharged. Verdicts in criminal cases were then returned. For guilty verdicts, cul. (culpabilis) was written on the indictment; if not guilty, non cul. Goods of felons could be seized, so juries were asked whether there were any; cat. null. (catalla nulla – no goods) was the usual response. The final question was whether the accused had fled; the answer was usually no, so nec retraxit was written.

Recognizances were then called over, the oldest first, and either discharged or continued. Anyone who had not appeared on a recognizance without good reason could be estreated. Bastardy and settlement cases were then heard, alehouse and badgers’ licences were granted, and general orders made. Sentencing then took place, and the Session came to an end. There was no appeal against most convictions and sentences at Quarter Sessions until 1907.

CRIMES AND MISDEMEANOURS

Common crimes in the early modern period included larceny, assault, riot, fraud and embezzlement. Quarter Sessions rarely tried anything more serious than petty larceny (that is, theft of goods valued at under 12d), frequently committed by vagrants and ‘wandering persons’. The details of goods stolen provide a useful insight into the nature of articles in daily use, and may usefully be compared with probate inventories. The places from which they were stolen are also interesting: sheep rustling from the village common was easy, burglary of a dwelling house more difficult.

Until the late eighteenth century, assault was frequently regarded as a matter for arbitration; Justices acknowledged agreement between the parties by imposing small fines. More serious cases, such as homicide, robbery with violence and burglary, were usually reserved for the Assizes. Two Marian statutes required Justices to certify examinations and informations of felons to Assizes. From 1590, Commissions exhorted the Justices to refer all casus difficultatis (difficult cases) to Assize judges. Cases could also be removed by writ of certiorari to a superior court, placing pressure on prosecutors to settle before costs mounted.

Quarter Sessions also dealt with misdemeanours, that is, offences against economic and social regulations. Failure to assist in communal tasks, such as refusal to serve as a parish officer, to perform statutory labour on the highways or to pay rates, might result in indictment. Those who blocked the highways with muck heaps, hedges, ditches and sheep folds, grew tobacco, or begged without a licence might appear. Unlicensed and disorderly alehouse keepers and their customers occupied much of the time of the Bench, which also kept an eye on their prices. There were no less than 480 presentments for alehouse offences at the Michaelmas sessions, 1619 in the North Riding of Yorkshire.28

Poaching and related offences, such as deer stealing and keeping game dogs, were common offences, since they offered poor men the opportunity to provide for their tables. Vagrancy was also an offence (see Chapter 8), but perhaps more frequently dealt with by parish constables and local Justices than by Quarter Sessions.

Trading offences, such as engrossing (unfairly buying up all the goods in the market and reselling them at a higher price), or conducting a trade without undergoing an apprenticeship, were frequent subjects of complaints under the Tudors and Stuarts. Disputes between apprentices and masters were common. Apprentices might be idle, dishonest, or abscond. Masters might inflict immoderate ‘correction’ or fail to provide for apprentices properly. Justices could cancel indentures or re-assign apprentices to new masters. Pauper apprentices are discussed in Chapter 8. Other relationships between masters and servants also came under scrutiny. Servants are discussed in Chapter 7, wages in Chapter 10.

Rioting could be a serious matter: in Oxford, racist riots against Welsh students in 1389 led to four deaths.29 Legally, a riot was anything done in a violent and tumultuous manner. Many were attempts to rescue persons under arrest. Others were protests against unemployment and famine. Many offences in Caernarvonshire probably stemmed from disputes over ownership of land.30

Attendance at church was expected by the community and enforced by law (see Chapter 9). The Puritans directed their ire at ‘profane swearers’, at alehouse keepers who sold drink at the time of divine service, at carriers who travelled on Sundays, at those who played ‘unlawful games’ and at anyone carrying on their trade on the Sabbath. Such offences could result in appearance before the Bench, although they were frequently dealt with by a single Justice or in ecclesiastical courts.

SENTENCING

The punishment for felony was death. The number of crimes liable to capital punishment increased from fifty in 1603 to over 200 by the early nineteenth century. The law, however, was intended to deter criminals, rather than to punish them – only a few instances of severity were needed to achieve deterrence. In practice, courts frequently mitigated penalties by reducing the seriousness of charges, or by recommending pardons. The accused could sometimes plead ‘clergy’, claiming that his ability to read proved his entitlement to trial in an ecclesiastical court – which could not impose the death penalty. Clergied offenders did, however, suffer branding. Benefit of clergy will be considered in more detail in Chapter 12.

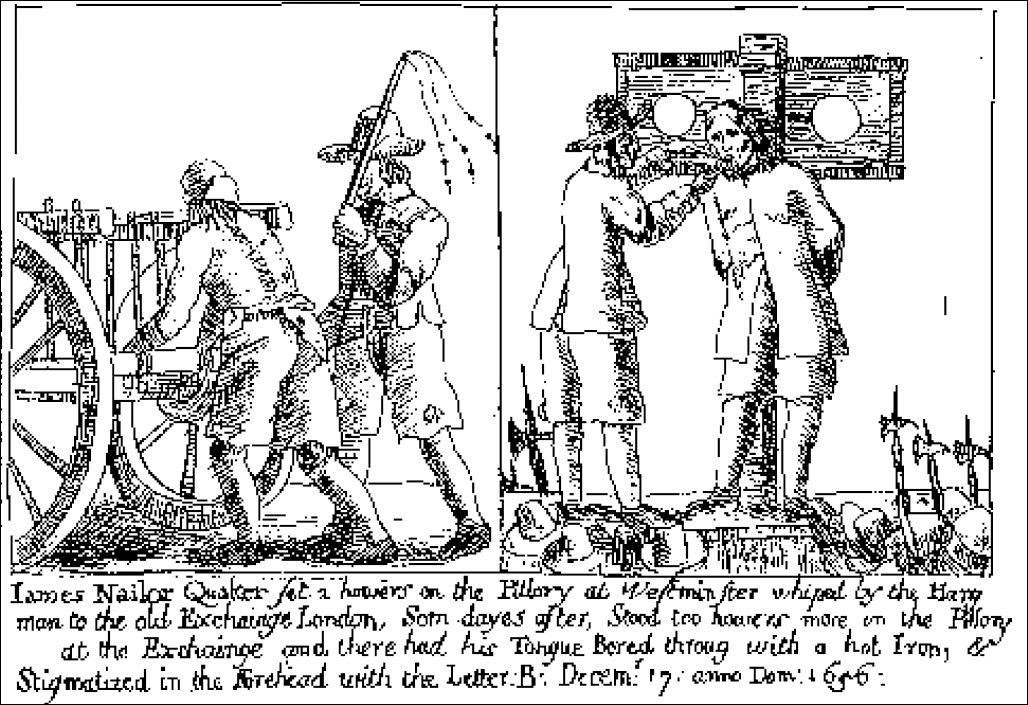

Branding, whipping, the pillory and hanging were standard punishments until the late eighteenth century. Minor offences might be punished by fines. The Bench took into account the fact that many convicts had been imprisoned before their trial, so had already been punished. Crimes thought to merit the death penalty were generally sent to Assizes.

In the early eighteenth century, the introduction of transportation caused major changes in sentencing practice. For the ensuing century or so, transportation to America, and subsequently to Australia, became a frequent sentence, and executions were drastically reduced. Sentences of imprisonment also replaced them. By c.1830, executions had ceased to be regular events, despite the number of capital offences still on the statute book.

Increasing public revulsion against violence was also demonstrated by the ending of public punishment for female offenders. But the same revulsion also led Justices to treat assault with much greater seriousness. The old practice of informal arbitration was abandoned. Similarly, juvenile offenders ceased to be treated with leniency.

Sentencing was also affected by considerations of cost. An execution could cost the county as much as £10 in fees. The cost of transportation averaged five guineas. Whipping and the stocks were much cheaper, and a fine produced income. Such considerations were not unimportant.

James Naylor created uproar during the Interregnum when he re-enacted Christ’s entry into Jerusalem. He was whipped at the cart’s tail, stood in the pillory, and had his tongue bored through.

JUSTICES AND THE LAW

Justices had a major influence on the development of English law. The confused state of statute law, the wide powers which Justices exercised over the lower classes, and limited supervision, gave Justices the opportunity to shape the law, and in some cases to drive reform. For example, vagrancy offered much scope for Justices of the Peace to ignore the formal law (see Chapter 8). Prison reform originated in the counties. Local Acts of Parliament, probably mostly influenced by Justices, far outnumbered public general Acts.

If the law became inconvenient, justices circumvented or ignored it. Late fifteenth-century Justices profited from enclosure, and ignored legislation against it. Settlement examinations (see Chapter 8) were frequently taken by a single Justice, although legally two had to be present. When the practice of imprisoning suspects before examination was ruled illegal in 1785, many Justices simply ignored the ruling, despite the potential for heavy damages.31 If Justices or juries thought that a penalty was too harsh, or were unhappy with a ruling from the central courts, they simply refused to convict. Gleaners (who collected leftover crops from farmers’ fields) knew that juries were unlikely to convict them of theft, despite Lord Loughborough’s 1788 ruling that gleaning was illegal. The letter of the law, and its practice, were sometimes two entirely different things.32

The early nineteenth century saw a number of procedural changes, introduced piecemeal, but dramatically altering the nature of criminal trials. Rules of evidence became much stricter, trials became more adversarial, and the defence of the accused was professionalised. A series of Acts in 1848–9 established standard court procedures, reduced Justices’ scope for manoeuvre, and confirmed the notion that only Parliament had the authority to initiate legal change.

ADMINISTRATIVE ACTION

In addition to criminal and civil cases, Quarter Sessions concerned itself with a wide range of administrative matters. Much time was taken up with Poor Law business. Roads and bridges were also important, as were rates and taxes. A wide range of other matters were dealt with, ranging from the management of county buildings, to the ransom of Turkish captives. In the early seventeenth century, Wiltshire Quarter Sessions were instructed to regulate the textile industry, to investigate complaints concerning the manufacture of saltpetre, and to put a stop to the cultivation of tobacco. They had to supply horses for postmasters, and to arrange the carriage of timber for the Navy.33 In the West Riding, the Bench took action to prevent the spread of plague in the 1630s and 1640s.34

The possibility of famine was never far from the minds of Tudor and Stuart Privy Councillors. They required Justices to prevent hoarding, engrossing, regrating (buying up grain to re-sell it in the same market) and non-essential use of corn. Producers of food were required to send it to market. Only the poor were allowed to make purchases during the first hour of a market. The Book of Orders issued in 1630 systematized Justices’ duties in these areas, aiming to moderate the symptoms of poverty before economic crises occurred. It insisted that Justices should regularly and systematically carry out their duties, and ensured they did so by instituting a reporting system which provided central government with regular reports from the Justices, via the Assize judges.35 Charles I made the most systematic attempt to ensure good local government before the nineteenth century. In the long run, he failed. After 1660, for 150 years, central government rarely interfered with Quarter Sessions in purely local matters.

Henceforward, Justices drove county policy, although the need for the Grand Jury to approve administrative action meant that it sometimes assumed responsibility itself, or at least acted as a finance committee. A 1739 Act required a presentment from the Grand Jury before money could be spent from county funds. That marked the high point of the Grand Jury’s involvement in administration. Subsequently, jurymen who held office for only one session, and who were increasingly unwilling to present anything, could not meet the dramatically increasing need for active administration.

County expenditure increased ten-fold between 1689 and 1835,36 as the population increased. The cost of maintaining roads, bridges, hospitals, lunatic asylums and gaols grew substantially. The creation of the Wiltshire Police Force in 1839 required a new police rate in 1840, which equalled the old county rate for all other purposes.37

Expenses were met by county rates, levied for specific purposes,38 although sometimes diverted to other purposes. Soldiers had to be paid, county bridges, hospitals, Houses of Correction and gaols had to be maintained; maimed soldiers had to be given pensions; vagrants had to be ‘passed’ (see Chapter 8); emergencies had to be met. Counties also contributed annually towards the maintenance of prisoners in the Marshalsea and King’s Bench.

Levying separate rates for all of these purposes was increasingly seen as inefficient. In the late seventeenth century some Benches experimented with a ‘regular, permanent general fund for various county purposes, to make collection and accounting easier’.39 In 1739, legislation consolidated the various different levies into a single rate. However, another separate rate was imposed by the Mutiny Act of 1809, which required Justices to pay for the provision of horses and oxen, with drivers and carriages, for armed forces marching through their jurisdiction. London Metropolitan Archives hold printed orders for Mutiny Rates c.1832–56. These give details such as average prices of hay and oats, types of carriages, the numbers of oxen or horses and the weight of loads.

The Marshalsea Prison, Southwark. From Walford, E. ‘Southwark High Street’, in Old and New London, Vol.6. 1878.

Most rates were paid by tenants, although occasionally the burden was shifted onto landlords. Assessment was according to ancient custom, usually based on land, but sometimes on goods, or on cattle. Some were levied across the whole county; others affected perhaps a Hundred, or even a particular parish. When Redditch was visited by plague in 1625, eleven neighbouring parishes were rated to provide support for the sufferers.40

Quarter Sessions set rates and notified High Constables, who apportioned the amount between parishes. Parish constables acted as collectors, paying sums collected to county treasurers. In 1844, rate-collecting became the responsibility of Poor Law Guardians. Quarter Sessions and Assize order books record details of the levies made, and perhaps their apportionment between the parishes. Ratepayers’ names may be recorded amongst parish records.

Financial administration was primitive until c.1800. Local Justices oversaw specific works, but county expenses were not properly scrutinised. Bills were simply presented to Quarter Sessions, and payment was ordered, or perhaps referred to a couple of Justices. The steadily increasing pressures of administration eventually led, in the 1790s, to the establishment of permanent committees, and the appointment of professional officers.

The earliest committees were the gaol visitors, who, after 1782, made regular reports to Quarter Sessions. By 1834, Gloucestershire had committees for finance, vagrants, bridges, weights and measures, and other matters. All accounts were submitted to the audit committee before being placed before Quarter Sessions.41 By contrast, Wiltshire only had a finance committee and visitors for the gaol and private lunatic asylums. To these were added committees for the constabulary (1839), visitors to the county asylum (1849), county rates (1870), licensing (1872), county bridges and highways (1876), boundaries (1883) and a joint committee with other counties on the River Avon fisheries (1866).

HUNDRED COURTS AND PETTY SESSIONS

In Chapter 1, we saw that each county had a number of administrative divisions, variously named. These divisions originally had their own courts. These were the ‘third kind of sessions’, according to Harrison, ‘holden by the high constables and bailiffs … wherein the weights and measures are perused by the clerk of the market for the county, who sitteth with them. At these meetings also victualers, and in like sort servants, labourers, rogues and runagates, are often reformed for their excesses.’42 Many Hundreds were private franchises; where this was the case, their courts were conducted by their lords. There were thirty-nine Hundreds in thirteenth-century Wiltshire; only twelve were in the King’s hands.43 Hundred courts were prone to corruption, frequently lacked impartiality, and became increasingly moribund in the early modern period.

As Hundred Courts withered away, Petty Sessions grew.44 Counties were too large to be effective judicial and administrative units. Divisional meetings of Justices of the Peace were held as early as the fourteenth century. Worcestershire Justices were holding regular ‘monthly meetings’ under Elizabeth.45 The Elizabethan Poor Law required Justices to meet annually in each locality to appoint overseers. The 1630–1 Book of Orders required divisional Justices to meet regularly. The Highways Act 1691 established separate highway sessions to appoint parish surveyors and supervise their activities. A Privy Council order of 1706 required the appointment of Justices in particular divisions to act against Roman Catholics.46 In the early eighteenth century, Kent Quarter Sessions ordered that alehouse licences, parish officers’ oaths, the approval of overseers’ accounts and the assessment of poor rates should all be matters for Petty Sessions rather than individual Justices. ‘Brewster’ sessions were held regularly from 1729 to licence alehouses. Eighteenth-century Petty Sessions became ‘the prime focus of judicial power’, acquiring clerks and doorkeepers.47 Quarter Sessions ceased to be the administrative body of first instance, but increasingly heard appeals from Petty Sessions, especially in settlement cases.

Firm statutory foundations were not provided for Petty Sessions until the Petty Sessions Act 1849, followed by the Prosecution Expenses Act 1851; the latter provided for the appointment of salaried clerks.

THE RECORDS OF QUARTER SESSIONS

The formal records of Quarter Sessions vary from county to county, but are likely to include order books, sessions rolls, process books and a variety of other documents. The names of a fair proportion of the lower orders, and most of the yeomanry and gentry, are likely to be mentioned in them.

Formal proceedings were recorded in order books or rolls. A number of fourteenth-century rolls were either collected during the itinerations of the Court of King’s Bench, or sent to King’s Bench or Chancery in response to writs. Some have been published and are listed below. When King’s Bench sat locally, Quarter Sessions ceased to operate, and the superior court heard its cases, which therefore had to be enrolled. When King’s Bench ceased to itinerate at the beginning of the fifteenth century, rolls were no longer required.

James I probably issued a general direction to commence keeping Quarter Sessions order or act books; many were begun in his reign. They contain formal orders of the court, both judicial and administrative. Some Clerks of the Peace experimented with keeping records before the formal series of order books commenced; in Wiltshire they commenced when the Clerk began keeping a register of badgers, and subsequently used that register as a notebook to record matters needing his attention.

At the end of each Sessions, Clerks prepared process or indictment books, listing indictments and presentments that required Sheriffs to take action. He also drew up the estreats,48 listing fines payable. Recusant rolls49 were sent to the Exchequer. Other paperwork, such as precepts, indictments, jury lists, calendars of prisoners, recognizances, presentments, examinations, petitions and reports, were generally gathered together in Sessions ‘rolls’ or files. The term ‘rolls’ is slightly misleading; the documents are frequently tied together with string, rather than stitched together and properly rolled up.50 Sometimes particular types of documents are filed separately. Most were written by Clerks of the Peace, Sheriffs, or Justices’ clerks.

Gaol calendars were written by the gaoler; they listed prisoners, offences, committing Justices and the date of committal. Those serving sentences, including any awaiting transportation to America or Australia, might also be listed.51 Sometimes calendars were annotated with the court’s judgement.

Indictments have already been described. However, pre-nineteenth century indictments can be misleading. Their purpose was very specific: to ensure that the accused received a proper trial. If they failed to follow the proper form, they could be thrown out for insufficiency. They were therefore worded very precisely, to describe offences against specific statutes, or identify specific common law offences. Accuracy in matters irrelevant to that purpose did not matter. Consequently, what actually happened is not always clear; the status of the accused was usually given as ‘labourer’ and his stated ‘residence’ was usually the scene of the crime. Dates on which offences were committed are not to be trusted.

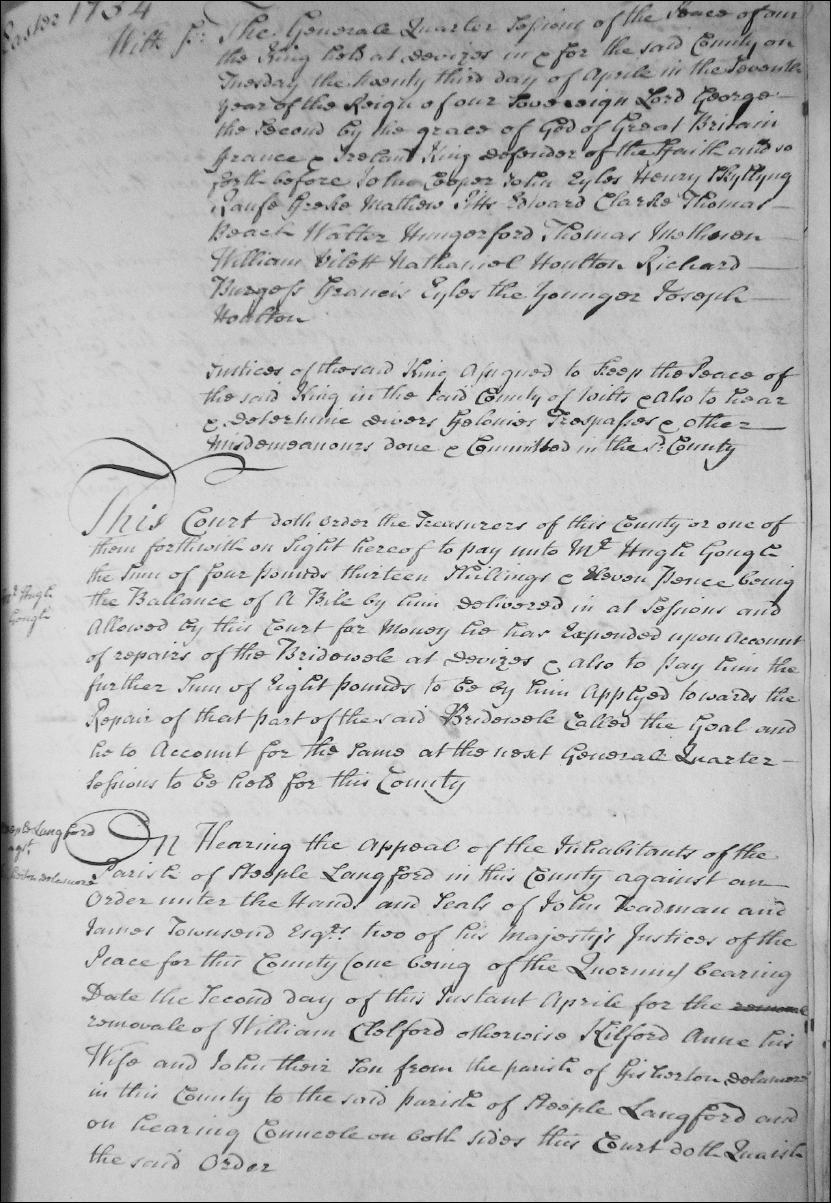

A page from Wiltshire Quarter Sessions Order Book. (Wiltshire & Swindon History Centre A1/160/6.)

Gaol Calendar for Wiltshire 1733. (Wiltshire & Swindon History Centre A1/125/6.)

Despite these problems, indictments have been used extensively in studying the history of criminality.52 Their evidence can be supplemented by examinations, depositions taken before Justices of the Peace, and recognizances (see Chapter 4), frequently filed with them.

A variety of other documents were also filed in sessions rolls. Jury lists are valuable sources of information on the lesser gentry and yeomanry. There are many letters from central government, concerning such matters as harvest failure, forced loans and purveyance. Many petitions were received, perhaps asking the Court for permission to erect cottages, or for a pension for a maimed soldier. They were sometimes annotated to record the court’s decision.

Quarter Sessions records can be found in county record offices, which were originally founded to house their records. Much has been lost; the hazards of damp, mice and fire were not easy to guard against. In 1800, the Worcestershire documents ‘and particularly the more ancient part of them [were in] an unceiled garret, entirely unarranged and insecure, and the residue irregularly placed in broken and old boxes’.53 In Cornwall, little survives before the eighteenth century. Prenineteenth century Petty Sessions records were particularly susceptible to disappearance: Petty Sessions clerks had no responsibility for keeping them.54 In Kent, eighteenth-century minute books survive, but generally records only become common after 1879, when clerks were required to deposit registers of convictions, depositions and certificates with Clerks of the Peace.55

Calendars of Quarter Sessions records for most counties can now be searched on The National Archives Discovery database http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk; many county record offices also have their own online catalogues. Lancashire order books have been digitised at http://search.ancestry.co.uk/search/db.aspx?dbid=6820.

FURTHER READING

For the criminal jurisdiction of Quarter Sessions and other courts, see:

• Beattie, J.M. Crime and the Courts in England, 1660-1800. (Clarendon Press, 1986).

The records of Quarter Sessions are summarily listed by:

• Gibson, Jeremy. Quarter Sessions Records for Family Historians: a Select List. (5th ed. Family History Partnership, 2007).

Many editions of Quarter Sessions order books, rolls, and other records are in print. Those with useful introductions used here are listed below. Early rolls for many counties are included in:

• Putnam, Bertha Haven, ed. Proceedings before the Justices of the Peace in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth centuries, Edward III to Richard III. (Spottiswoode, Ballantyne & Co., 1938).

• ‘Sir William Boteler’s charges to the Grand Jury at Quarter Sessions, 1643-1647’, in Lee, Ross, ed. Law and Local Society in the Time of Charles I: Bedfordshire and the Civil War. (Bedfordshire Historical Record Society 65, 1986), pp.57–110.

Cheshire

• Morrill, J.S. The Cheshire Grand Jury 1625-1659: a Social and Administrative Study. (Leicester University Dept. of English Local History occasional papers 3rd series 1, Leicester University Press, 1976).

Dorset

• Hearing, Terry, & Bridges, Sarah, eds. Dorset Quarter Sessions Order Book, 1625-1638: a Calendar. (Dorset Record Society 14, 2006).

Durham

• Fraser, C.M., ed. Durham Quarter Sessions Rolls, 1471-1625. (Surtees Society 198, 1991).

Essex

• Allen, D.H., ed. Essex Quarter Sessions Order Book, 1652-1661. (Essex Edited Texts 1. Essex Record Office Publications 65, Essex County Council, 1964).

Gloucestershire

• Kimball, Elisabeth Guernsey, ed. ‘Rolls of the Gloucestershire Sessions of the Peace, 1361-1398’, Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 62, 1940, p.112.

• Wyatt, Irene, ed. Calendar of Summary Convictions at Petty Sessions, 1781-1837. (Gloucestershire Record Series 22, Bristol & Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, 2008).

Hertfordshire

• Hardy, W.J., et al, eds. Hertford County Records. 10 vols. (Hertford: C.E. Longmore, et al, 1905–57).

• Putnam, Bertha Haven, ed. Kent Keepers of the Peace, 1316-1317. (Kent Records. Kent Archaeological Society Records Branch 13, 1933).

• Knafla, Louis A., ed. Kent at Law 1602: the County Jurisdiction: Assizes and Sessions of the Peace. (HMSO, 1994).

Lancashire

• Quintrell, B.W., ed. Proceedings of the Lancashire Justices of the Peace at the Sheriff’s Table during Assizes week, 1578-1694. (Record Society of Lancashire and Cheshire 121, 1981).

• Tait, James, ed. Lancashire Quarter Sessions Records. Vol.1. Quarter Sessions Rolls, 1590-1606. (Chetham Society New Series 77, 1917).

Lincolnshire

• Sillem, Rosamund, ed. Records of Some Sessions of the Peace in Lincolnshire, 1360-1375. (Lincoln Record Society 30, 1936).

• Kimball, Elisabeth G., ed. Records of some Sessions of the Peace in Lincolnshire, 1381-1396. Vol.1. The Parts of Kesteven and the Parts of Holland. (Lincoln Record Society 49, 1955).

• Peyton, S.A., ed. Minutes of Proceedings in Quarter Sessions held for the Parts of Kesteven in the County of Lincoln, 1674-1695. Part 1. (Lincoln Record Society 25, 1931).

Middlesex

• Jeaffreson, John Cordy, ed. Middlesex County Records. 4 vols. (Middlesex County Records Society, 1886–91). Covers 1550–1688.

• Hardy, W.J., ed. Calendar of the Sessions Books, 1689 to 1709. (Sir Richard Nicholson, 1905). Continued to 1752 in typewritten volumes in the British Library.

• Hardy, William Le, ed. County of Middlesex: Calendar to the Sessions Records. New series. 4 vols. (Middlesex County Council, 1935–41). Covers 1612 to 1618 in more detail.

Northamptonshire

• Gollancz, Marguerite, ed. Rolls of the Northamptonshire Sessions of the Peace; roll of the Supervisors, 1314-1316; roll of the Keepers of the Peace 1320. (Northamptonshire Record Society Publications 11, 1940).

• Wake, Joan, ed. Quarter Sessions Records of the County of Northampton. Files for 6 Charles I and Commonwealth (A.D. 1630, 1657, 1657-8). (Northamptonshire Record Society Publications 1, 1924).

Oxfordshire

• Kimball, Elizabeth G., ed. Oxfordshire Sessions of the Peace in the Reign of Richard II. (Oxfordshire Record Society 53, 1983).

• Gretton, Mary Sturge, ed. Oxfordshire Justices of the Peace in the Seventeenth Century. (Oxfordshire Record Society 16, 1934).

Shropshire

• Kimball, Elisabeth G., ed. The Shropshire Peace Roll, 1400-1414. (Salop County Council, 1959).

Somerset

• Shorrocks, Derek, ed. Bishop Still‘s Visitation, 1594, and the ‘smale booke’ of the Clerk of the Peace for Somerset 1593-5. (Somerset Record Society 94, 1998).

• Bates, E.H., ed. Quarter Sessions Records for the County of Somerset. (Somerset Record Society 23–4, 28, & 34, 1907–19). Covers 1607–77.

Staffordshire

• Burne, S.A.H., et al, eds. The Staffordshire Quarter Sessions Rolls. 6 vols. (Collections for the History of Staffordshire 3rd series, 1929–49). Covers 1581–1609.

Surrey

• Powell, Dorothy L., & Jenkinson, Hilary, eds. Surrey Quarter Sessions Records: Order Book and Sessions Rolls, 1659-1661. (Surrey Record Society 13, 1934). Also published by Surrey County Council. Further vols. cover 1661–3, 1663–6, and 1666–8.

Wiltshire

• Johnson, H.C., ed. Wiltshire County Records: Minutes of Proceedings in Sessions, 1563 and 1574 to 1592. (Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society Records Branch 4, 1949).

• Fowle, J.P.M., ed. Wiltshire Quarter Sessions and Assizes, 1736. (Wiltshire Archaeological & Natural History Society Records Branch 11, 1955).

• Slocombe, Ivor, ed. Wiltshire Quarter Sessions Order Book, 1642-1654. (Wiltshire Record Society 67, 2014).

Yorkshire

• Putnam, Bertha Haven, ed. Yorkshire Sessions of the Peace, 1361-1364. (Yorkshire Archaeological Society Record Series 100, 1939).

• Lister, John, ed. West Riding Sessions Rolls 1597/8-1602. (Yorkshire Archaeological and Topographical Society Record Series 3, 1888).

• Lister, John, ed. West Riding Sessions Records, vol.II. Orders 1611-1642; Indictments 1637-1642. (Yorkshire Archaeological Society Record Series 54, 1915).

Caernarvonshire

• Williams, W. Ogwen, ed. Calendar of the Caernarvonshire Quarter Sessions Records. Vol.1. 1541-1558. (Caernarvonshire Historical Society, 1956).

Merionethshire

• Williams-Jones, Keith, ed. A Calendar of the Merioneth Quarter Sessions rolls. Vol.1. 1733-1765. (Merioneth County Council, 1965).