5

The Roots of Sunni Militancy and its Enduring Threat in Iraq

In the autumn of 2003, Khaled, a former intelligence officer based in Baghdad, was witnessing his country turn into a war zone. He, like many of the other moderate Sunni men who had previously worked for the regime, was left on the periphery following Paul Bremer's process of de-Baathification. With a wife and small child to support, Khaled was forced to seek work outside of the government for the first time in his life. Despite finding low-paid work in a local shop, the conditions around Khaled and his family deteriorated, hastened by the emerging sectarian war in 2006 and 2007. During this uncertain period, whilst standing outside his place of employment, men claiming to be ‘friends of a friend’ approached him: ‘We have been told that you are a good man, Haji [pilgrim – a respectful term for a man of Muslim faith]. We are going to Fallujah to join the resistance and would like you to come with us.’1 The men, who were Sunni and all former military, had been asked by friends and resistance leaders in Anbar to collect as many Sunni ex-servicemen as possible for the ‘fight ahead’. At a crossroads in his life, Khaled declined and explained to the men that he had his own personal ‘jihad’, one that involved the survival of his family.

Many others in Khaled's position chose a different path, including those who went on to be leaders in the resistance movement and, later, ISIS. One such was Abu Ali al-Anbari, a former general in the Iraqi army before joining the Wahhabi-inspired Ansar al-Sunna, AQI and ISIS. A similar timeline also applies to Fadel Ahmed Abdullah al-Hiyali, also known as Abu Muslim al-Turkmani, another former general with moderate religious views.2 The turn to Sunni militancy was therefore a choice, one that was heavily restricted by the prevailing circumstances, but one nonetheless that was based on survival. The occupation therefore triggered a response from within an uncertain Sunni community, one that became enmeshed in a sectarian struggle regardless of choice.

The enduring threat of Sunni militancy in Iraq is rooted in the conditions from which it has emerged and evolved. Religion has long been used as a means of securing loyalty and as a mechanism of control, yet such efforts also have consequences for regional conditions and dynamics. ISIS is a symptom of these conditions and an organisation that has thrived on the factors already mentioned in this book. Therefore removing it as a main force from Iraq and its control over cities such as Mosul and Fallujah will only provide temporary respite, as the long-standing issues driving Sunni militancy will ultimately remain. To show this, this chapter will focus on the conditions and factors that influence Sunni militancy, building on the conditions across the state in the run-up to the 2003 invasion. The violence that was triggered via the invasion will be discussed with reference to Sunni militancy and the groups that helped forge the response. The second part will pay particular attention to ISIS and how a myriad of factors allowed it to establish its roots in Sunni communities across Iraq. The third part will highlight the enduring threat of Sunni militancy and the potential for future stability in Iraq. Quantitative data and qualitative research will be used to highlight the enduring threat of Sunni militancy amidst Iraq's fragmenting conditions.

The road to Sunni insurgency in Iraq

The foundations for Sunni Islamism and militancy had already begun before 2003. Irredentism, ethnic and sectarian tensions, social cleavages and political suspicions had long existed within Iraq's borders, but these factors were exacerbated following two Gulf wars and the imposition of economic sanctions. As Saddam's control over peripheral areas wilted, new actors emerged in the provincial areas. Tribal factors played an important role in organising communities, but religion also became a galvanising force. In an attempt to reinforce his own leadership, Saddam introduced Hamla al-Imaniyya or ‘return to faith’ in 1991, evoking Islamic values under the country's duress. However, without the necessary funds for public investment, economic conditions soon affected the very core of society. Saddam introduced Islamic schools and colleges in his name, but without finance even the education sector faltered. As Hashim3 highlights, school enrolment between the years 1990 and 1994 decreased from 56 per cent to 26 per cent, while adult literacy was reduced from 89 per cent to 59 per cent between the years 1985 and 1995. Nevertheless, as a result of Saddam's policies new generations of religious Sunnis were created, one of whom was Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, who attended the Islamic University of Baghdad.4

The turn to conservative religious values in periods of hardship is not uncommon, and despite Saddam's suppression of Sunni organisations such as the Muslim Brotherhood, there existed a trend for such a retreat into religious identities. It would therefore be plausible for Saddam to think that he could utilise religion for his own political gain. He was also aware of the challenge posed by the Shi‘a political and religious opposition in Iraq and therefore he could use his own version of Sunni Islam to counteract the religious forces emerging from Shi‘a communities. This was particularly evident in the southern provinces like Najaf and Karbala and across the southeast where the building of communities around mosques was an increasingly common theme. While there was little sign of a unified front amongst Shi‘a political and religious circles, pro-Iranian opponents of the regime were nevertheless keen to take advantage of the apparent weakness of government. To this end, Saddam used violence and coercion to maintain control, but he also recognised the utility of religion as both a counter-narrative and a motivational tool. He used it to chastise Saudi Arabia and Syria during the second Gulf War5 and even called Iraq the ‘land of jihad’ during a speech in 2002.6

While maintaining the basic tenets of Baathism, Saddam fused his interpretation of Iraqi nationalism with various religious groups and movements, attempting to maintain control in the peripheral areas, including the Kurdistan region, much as he did with the tribes. In an interview with two former military officers7 who had served under Saddam's regime, they recalled how various beliefs were used as control mechanisms against potential threats or as a way of balancing against other religions. In one particular example, ‘connections with Sufis in the north through Izzat al-Douri served a purpose during the early 2000s, but many of us (senior military officers) were uncomfortable with their practice, which seemed to be based on magic rather than religion’.

By the start of the Sunni insurgency, the roots of disaffection and the drivers of militant mobilisation had already been established, with several supporting a blend of Iraqi religious nationalism. For example, the Sufi-labelled Jaysh Rijal al-Tariqa al-Naqshbandia (JRTN) did not officially mobilise as an insurgent group until 2006, following the execution of Saddam Hussein; however, with Izzat Ibrahim al-Douri, the former deputy head of the Revolutionary Command Council under Saddam Hussein,8 as the apparent leader of the organisation, a dynamic between Baathism and religion already existed. After 2006, the JRTN used these links to mobilise supporters within Sunni Arab communities in the provinces Kirkuk, Ninawa and Salahaddin in particular, while creating alliances with other similar religious–national organisations, such as the Islamic Army of Iraq (IAI). The IAI, led by Sheikh Ahmed al-Dabash, was also reportedly established before 2003,9 but its ranks were bolstered by Sunni Iraqi nationals after the invasion, a number of whom also had links to the military. The IAI has also maintained a connection with prominent members of the large Jabouri tribe in particular, and thrived in areas north of Baghdad. IAI has purported a more nationalist version of Sunni Islam, but, under conditions exacerbated by the occupation and sectarian conflict, found commonalities with a number of other insurgent groups, many of whom were Islamist in ideology, such as AQI.

Supporting this growth in Islamism, foreign fighters were also able to take advantage of the porous borders, allowing them to travel to the region. At the time, Kurdistan was particularly isolated, a peripheral region in the north. Despite being composed predominantly of Kurdish and Iraqi Arabs, it became an ideal place for Salafis and foreign radicals alike,10 some of whom were from Saudi Arabia and Yemen, while others came from further afield. This was noted by former officers who recalled information on ‘Saudi-sponsored Salafis from the Caucasus and the Balkans’,11 many of whom had prior experience in places such as Chechnya, Bosnia and Afghanistan. Some Kurdish media reports even speculated that Saddam was sending arms to Salafis in the region, with Ansar al-Islam being a case in point,12 following their creation in Kurdistan in 2001. Initially called Jund al-Islam, with links to Al Qaeda, it was also known as Ansar al-Sunna, a name that became apparent following a split within Ansar al-Islam in 2003.13 It regrouped as Ansar al-Islam in 2007.14

As the occupation took hold then, other Sunni militant organisations emerged, drawing their energy from the sectarian conditions and uncertainty within the Sunni community, including religious advocates, former members of the army, and Sunni tribes and clans. One such example was the 1920 Revolutionary Brigades, led by Dr Mohammed Mahmoud Latif (also known as Sheikh Mahmoud al-Fahdawi). Latif, a Shariah Law scholar from Sofia near Ramadi in Anbar province, led the Revolutionary Brigades in the area referred to as the Sunni triangle, comprising Anbar, Baghdad (including its belt areas), Diyala,15 and particularly in southern parts of Salahaddin province, in towns such as Tarmiya and Taji. Another organisation of Islamist leanings was Jaish al-Mujahideen or the Mujahideen Army (MA). According to its leader Abd al-Hakim al-Nuaimi, MA was a religious organisation before the occupation, and according to spokesperson Abdul Rahman al-Oaisi the group was even providing social services including religious education and charity.16 It established its roots in central and eastern areas in Anbar province, in towns such as Karma, before becoming active in the insurgency in 2004.

Both Sunni national and religious organisations therefore joined the insurgency against the occupying forces, while rejecting the Shi‘a-dominated government. In the early stages, AQI became the de facto leader of the insurgency, working alongside groups like IAI and Ansar al-Islam. In 2005, an organisation composed of AQI and several other groups, calling itself ‘Islamic State in Iraq’, took over the Sunni majority city of Mosul, in Ninawa province in the north of Iraq. In establishing its own rule, it benefited from kidnapping and extortion from local businesses, justifying it as a type of legitimate taxation.17 However, as a consequence of their popularity both locally and globally, they also became the primary focus for US operations in the area. Despite not having a footing in Iraq prior to the 2003 invasion, conditions in the country drew in Al Qaeda and foreign Jihadists as they flocked to take part in a fight against the US-led forces, which they saw as a religious – and personal – duty. In an interview with Atlantic Magazine in 2006, known Palestinian–Jordanian jihadist, Huthaifa Azzam,18 stated that:

I was in Syria when the war in Iraq began […] People were arriving in droves; everyone wanted to go to Iraq to fight the Americans. I remember one guy who came and said he was too old to fight, but he gave the recruiters $200,000 in cash. ‘Give it to the mujahideen,’ was all he said.19

When Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, AQI's Jordanian-born leader and one-time jihadist colleague of Azzam, was killed in an airstrike in 2006, it was considered a watershed moment. Yet AQI (or AQI–ISIS for that matter) were not the driving factors behind Sunni militancy, but as with ISIS, were a symptom of the circumstances that have emerged over a much longer period, triggered by the invasion in 2003. It was during this period that the landscape had changed and the majority of Iraq's Sunni Arabs found themselves on the periphery, facing increasing uncertainty under a majority Shi‘a government and the growing strength of Shi‘a militias. AQI and its affiliate, ISIS, were created under these circumstances and sought to take advantage amidst the chaos. AQI-ISIS established trade and financial networks, but as time elapsed, their desire to control the insurgency and finances in areas where it was established led to increased discontent amongst other Sunni Arab groups, tribes and communities. Yet in the short term, the group was able to draw support from the disaffected Sunnis who were struggling to meet their basic needs.

Breaking Al Qaeda

The Sunni insurgency was a melting pot of disaffected former soldiers, tribal members, Islamists – both local and foreign – and Baathists. The US-led forces approached the matter as a problem to be eradicated, conducting numerous military offensives and anti-terrorist operations, often in coordination with Iraq's newly founded security forces, which they themselves were involved in training. The Awakening or Sahwa programme with the tribes had an important role in this, and by late 2007 the tide against the insurgency had begun to turn. For example, Ansar al-Islam created an alliance with other Sunni and national militant groups such as IAI and MA in the hope of projecting a more moderate position than that of AQI without giving up on their position against the occupying forces and the Iraqi government.20 The IAI itself officially announced its parting from AQI-ISIS in April 2007, and with evidence of momentum shifting in favour of the anti AQI-ISIS movement, Mishan al-Jabouri, a prominent former Baathist and tribal leader, used his IAI-affiliated media channel, al-Zawraa, to condemn AQI-ISIS.21

Other groups like the 1920 Revolutionary Brigades were more divided over their support for the insurgency. Although this organisation is Iraqi, its Islamist tendencies meant many of its members had much in common with AQI-ISIS. Yet being from Anbar, its leader Mohammed Mahmoud Latif was all too aware of the problems caused at the local level by AQI, and his rapprochement with the Sahwa movement through relations with Sheikh Sattar al-Rishawi epitomised the shift in balance. Nevertheless, those that did not support the Sahwa left the organisation and formed Hamas in Iraq.22

At the local level, being part of the Sahwa was paying dividends, an effective recruitment process for more organisations and individuals to join the cause. As momentum shifted, the Sahwa proved a highly effective short-term strategy and many of the insurgents that were not killed were either forced underground or placed in prison camps. Nevertheless, this did not remove the threat of Sunni militancy in its entirety. According to al-Bawaba, a Jordanian media outlet, following al-Maliki's military campaign to completely remove AQI-ISIS from Mosul in May 2008, the organisation merely adapted and, according to a contractor, they went underground and ‘instead of targeting homes and businesses with explosive devices, al-Qaeda started kidnapping and assassinating’.23

Even in prisons, the legacy of internment created conditions that facilitated radicalisation, through the detainment of a number of Sunni insurgents, ultimately proving favourable recruitment ground for groups like ISIS. During the occupation the USA reportedly detained 100,000 people in Iraq,24 both Sunni and Shi‘a. Of these, approximately 26,000 were based in Camp Bucca, a desolate facility near Garma in the south, close to the Kuwaiti border. Prisoners were divided along sectarian lines, and the inmates themselves implemented a code of Islamic law to govern their everyday lives. It is here that figures like ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi were groomed amidst an environment of radical insurgents and Islamists. Al-Baghdadi himself was incarcerated in 2004 but released in 2007,25 after which he went on to join the AQI branch of Islamic State. A former intelligence officer26 stated, ‘there were many young men who were in these prisons already part of the insurgency, but when they were released and returned to their homes, they were now wearing beards and short trousers (in reference to the Salafi trend)’. He continued, ‘That was one of our fundamental errors, we never monitored these guys. I remember a young man I use to know, from a good family, but when he was released he returned to little Fallujah [Adhamiyah district, a predominately Sunni area in Baghdad], where he became attached to a mosque known to be linked to al-Qaeda.’27

Insurgent detainees were being released before the end of 2009, and several of the prison camps including Camp Bucca were closed. Despite this, there was little in the way of a reintegration programme for former prisoners and, as Thompson and Suricot note, ‘Poor record-keeping, limited language skills, detainee obfuscation and the pressure to cut costs prohibited the effective evaluation of prisoners.’28 Due to resource limitations, neither the US nor the ISF were able to control the situation and, while some of the worst insurgents were moved to other prisons, those that were freed re-entered the same uncertain society that had governed Sunni communities since 2003, where there was very little in the way of political or socio-economic improvements.

The ‘purge’, as it has been referred to by the Americans, proved successful in reducing the Sunni militant threat and, by the time US forces left in December 2011, it is estimated that AQI-ISIS had diminished to approximately 10 per cent of its peak capacity during the insurgency.29 However, the failure to introduce political and economic reform across the sectarian divides never materialised under the government of Nouri al-Maliki, and while the unbalanced conditions existed the threat of Sunni militancy was unlikely to disappear. Added to this, a number of the hardline radicals and Islamists (such as ISIS leader al-Baghdadi) were merely pushed underground, but they never went away and instead continued their asymmetric campaign against the government of Iraq and any opposition. As the situation slowly deteriorated and protests escalated in Sunni communities, tribal organisations (as noted in the previous chapter) and militant factions mobilised, and by 2012 a new war was beginning.

Making ISIS in Iraq and Syria

Although AQI-ISIS continued to operate in Iraq, the conflict in Syria, which began in March 2011, provided the chaotic conditions for the organisation to regroup and ultimately flourish. Porous borders and a reduction in sovereign control allowed for the influx of weapons and foreign fighters into Syria openly supported by countries opposed to Assad's regime. Al Qaeda affiliates Jabhat al-Nusra and other groups such as the Saudi Arabian-backed Jaish al-Islam30 acted quickly to capitalise on grievances in predominately Sunni areas, filling the power vacuum east of Assad's control. However, as the war evolved it was the emergence of ISIS that began to command most of the attention. By the end of 2013, despite the success of aligned rebels and other Sunni militant groups, ISIS had managed to embed itself in cities, towns and villages spanning from Aleppo in the west to Raqqa in the east (its Syrian stronghold) and the border areas with Iraq, gaining control of oilfields and trading networks in the process. In slowly establishing the tenets of what it believed to be an Islamic State, ISIS's actions brought it into direct confrontation with other anti-regime groups including Jabhat al-Nusra, with which it had aligned at the onset of the conflict. As with other organisations in the past such as Al Qaeda in Iraq, ISIS knew the benefit of controlling resources and trade routes. By the end of 2013 it had ‘alienated most of the rebel groups by creating smothering checkpoints, confiscating weapons and imposing its ideology on the local population’.31 In February 2014, Al Qaeda officially distanced itself from ISIS, claiming it ‘is not a branch of the al-Qaeda group’ and ‘does not have an organizational relationship with it and [Al Qaeda] is not the group responsible for their actions’.32 Such tensions also arose between Al Qaeda and AQI under the leadership of al-Zarqawi.

Nevertheless, the appeal of ISIS to Sunni communities in Syria bore similar traits to AQI after 2003. ISIS infused itself amongst the tribal networks in peripheral areas, and as Dukhan and Hawat33 note, a combination of economic strength, the instilling of fear and presenting itself as a valid alternative to the threat posed by Assad's regime (one could even include its supporters Iran in this), it was able to offer a semblance of order amidst increasing uncertainty and chaos. Indeed, with control of logistic routes and oilfields spanning across both Syria and Iraq, ISIS has been well placed to provide economic incentives and socio-economic support. Beyond their defined military objectives, Stephen McGrory, a security and humanitarian consultant, notes that a number of actors in the Syrian conflict implicitly recognise the importance of garnering local support and seek to achieve this through the provision of social services:

The regime has prioritized the steady supply of flour and fuel to bakeries in areas still under government control, while attempting to disrupt this in opposition areas. A pattern has emerged over the past four years of the regime specifically targeting bread supply – bakeries, fuel, wheat flour supplies and entire wheat crops – in areas where it has lost territory.34

As McGrory notes, however, anti-Assad elements are equally adept in this process.

ISIS and Jabhat al-Nusra have replicated the regime's focus on bakeries by an equivalent prioritisation on the distribution of cheap bread as a critical enabler to establishing, and maintaining, popular support from ‘liberated’ communities […] ISIS in particular has a clear, patient and long-term policy of promoting bread as a critical social service by distributing flour and fuel to functioning bakeries, and actively supporting the reconstruction of damaged bakeries and supply lines once an area has been taken. In addition, there is evidence of bread being distributed for free, by fighters, and often deliberately provided to the most vulnerable, poor and food-insecure groups within contested communities.’

For McGrory, ISIS capitalised on the vacuum in governance to consolidate its control and ultimately legitimise the Islamic Caliphate, presenting itself as a long-term solution to the region's uncertainty. To guarantee this foothold, it also applied a basic fiscal policy, applying taxation to material items, businesses and salaries, while simultaneously regulating trade. ISIS has therefore utilised local workers and networks to generate its income via general acquiescence. For example, oil from ISIS-controlled areas has reportedly been sold to local businesses, Assad's regime35 and even to neighbouring countries such as Turkey.36 It is precisely this complex network of actors that makes removing ISIS extremely difficult. Air strikes against its oil convoys for example may reduce ISIS profits, but at the same time they also remove the livelihoods of the local tribes and communities who rely on the work for their own sustenance, simultaneously weakening ISIS and deepening the grievances amongst the very communities that the West seeks to empower.

By June 2014, political and security conditions in Iraq had decreased sufficiently to allow ISIS to cross from Syria to Iraq in considerable military force, with little in the way of resistance. Once again utilising local networks and the efforts of other Sunni militant organisations, it eventually assumed de facto control of western border areas and main cities and towns. Firstly, it established its presence in Anbar province, in populated areas such as Qaim, Rawa, Rutbah, Hit, Fallujah, Karma and other smaller areas and, following this, to the north in Sinjar, Tal Afar, Mosul, Hawijah, Baiji and Tikrit. They even established footholds in the Baghdad belt areas, notably in the mixed populated provinces of Diyala, Babil and Salahaddin. Control over much of this territory and the logistic routes enabled ISIS to obtain a degree of financial autonomy and, with it, to offer a degree of protection and welfare to those in its territory. It is estimated that ISIS has generated in the region of US$80 million per month from its financial activities in both Syria and Iraq, with approximately 50 per cent obtained through taxation and the confiscation of items, and oil trade accounting for 43 per cent.37

Between two fragmented states, ISIS has projected itself as the custodian of an Islamist utopian society and at the vanguard of a fundamentalist Sunni Islamist movement, dedicated to violently defending its beliefs. This has been presented to an international audience through social media, causing shock, outrage and demands for a military response. Nevertheless, it is important not to lose sight of the circumstances and conditions that have combined to forge the situation where ISIS has emerged. The fragmentation of both Syria and Iraq is a consequence of a much more complex set of interactions that have occurred over a longer period of time. It is therefore through this melange of interactions that we have arrived at the current landscape, where the conditions for Sunni resistance and militancy have been cultivated.

Sunni militants re-energised in Iraq

By the summer of 2013, Iraq's major Sunni towns and cities were in open revolt against the Shi‘a-led government.38 Deteriorating socio-economic conditions along with a worsening security landscape enabled groups such as ISIS to grow in popularity and to establish footholds in Sunni communities, particularly in the western border areas of Anbar province. The border with Syria had been notoriously difficult to control, with a legacy of smugglers and tribes profiting from the lack of security and even applying their own form of governance. Controlling the border areas within the province, particularly Syria and Jordan, while maintaining tribal networks across the borders was – and remains – vital to preserving the trade and logistic routes vital to sustaining a programme of self-sufficiency.

By the summer of 2013, ISIS fighters in Iraq had asserted their authority on routes and towns near the borders in Anbar. In August of the same year, a YouTube video was posted showing the killing of three truck drivers of reported Alawite origin in the border area of western Anbar, on the main route to Baghdad.39 The man who led the execution of the Syrian drivers wore long hair, a beard and combats, in the style now synonymous with ISIS fighters. Highlighting ISIS's ideology and radical militancy, the video also showed how ISIS used its local leverage to operate in strategically important areas, with impunity.

The man who conducted the executions was Shakir Waheeb al-Fahdawi, formerly of AQI and a Camp Bucca detainee, having been arrested by US soldiers in 2006 while fighting in Anbar. Being from the al-Fahdawi tribe (Dulaymi confederation), Waheeb's roots are in Anbar province or more specifically al-Madhaiq, a small village east of Ramadi where most of his family still reside. According to a source from al-Madhaiq ‘Waheeb was a normal boy from a good family’ but was drawn to the resistance movement and became more radical following his experiences of war and imprisonment, apparently threatening ‘he would kill his own family for not supporting Daesh’.40 Following the closure of Bucca, Waheeb was transferred to Tikrit where he was to await his own execution; however, he escaped following an attack on the prison – a strategy regularly employed by ISIS fighters – in 2012. Since then, he has become somewhat of a poster figure for ISIS and, according to sources in Anbar, instrumental in organising offensives in Fallujah and Ramadi during ISIS's large-scale conquests.

Shakir Waheeb's timeline offers a useful case study of how domestic conditions have produced a local ISIS fighter, but it also highlights failures in Iraq's security apparatus. Nevertheless, in 2013 ISIS was only one of many groups vying for a foothold in Iraq and their violent actions had already drawn much criticism from within Sunni tribal and political quarters. In response to the changing conditions, alliances developed once more and in January 2014 al-Majlis al-Askari li-Thuwar al-Asha'ir al-Iraq, or Military Council of Iraqi Tribal Revolutionaries (GMCIR), officially announced its formation on Twitter. The GMCIR was composed of a network of tribes, former military personnel, Sunni militant group members and religious leaders such as Sheikh Harith Sulayman al-Dhari of the Muslim Scholars Association. The grouping had been under formation since the summer of 2013, but projected itself as a legitimate leadership council for revolutionary groups of Sunni denomination across Iraq.41 According to research conducted by Heras,42 there were 75,000 fighters associated with the GMCIR concentrated in the provinces of Anbar, Salahaddin and Ninawah, with armed affiliates in Baghdad, Diyala, Kirkuk and amongst the predominately Shi‘a provinces Karbala, Dhi Qar and Maysan in the south of Iraq. It also drew on external networks in Jordan, Turkey, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, many of whom were also able to tap into networks in their residing countries that had similar issues with the pro-Iranian agenda in Iraq.

At the local level, prominent members of the GMCIR included former Baathists within the JRTN,43 who had established a strong presence in the emerging resistance movement in Kirkuk and Ninawah provinces in the north of the country. The majority of the GMCIR's members were tribal fighters, many of whom had participated in the Sahwa programme and took up arms once more as uncertainty in their communities heightened. Some of these former Sahwa members joined other local councils, several of which overlapped with the GMCIR through its members and affiliates. For example, across the provinces of Anbar, Salahaddin and Ninawah, a number joined the Military Council of the Tribal Revolutionaries (MCTR). Many of these same fighters and others in Anbar chose to join Sheikh Ali Hatem al-Suleiman's Military Council of Anbar Tribal Revolutionaries (MCATR), including fighters from within the Dulaymi confederation of tribes, such as the Albu Nimr and Albu Issa as well as members from the al-Jabbouri and al-Janabi.44 While calling for autonomy, these groups targeted government security forces in what they believed to be part of a legitimate resistance movement. They were joined by the Fallujah Military Council (FMC), a non-GMCIR aligned (but with affiliations) collection of militant groups led by the Salafist Abu Abdullah al-Janabi, a former senior member in the Mujahideen Shura Council of Fallujah post-2004 that had AQI as a part of it.45 This time around, the FMC included former members of the 1920 Revolutionary Brigades via the new title of Hamas in Iraq, the Islamic Army of Iraq and, of course, ISIS.46

Despite evident ideological and strategic tensions between the various councils and particularly ISIS, there existed a common goal and a strong enough network between the tribes and various militant groups to establish an operational understanding. For example, as members of the Sunni insurgency in Anbar consolidated their control over its villages and towns, the ISIS-led attack on Mosul in June 2014 further stretched Iraq's security forces. In an interview in June 2014, Ahmed al-Dabbash, leader of the IAI, declared this was part of a larger movement: ‘Is it possible that a few hundred ISIS jihadists can take the whole of Mosul? No. All the Sunni tribes have come out against Maliki.’47 However, al-Dabbash, like many of the other factions involved with the large-scale assault, believed its relationship with ISIS was one of convenience in what was supposed to be an holistic effort to establish an autonomous region, and therefore a relationship that could be controlled considering the relative size of ISIS's organisation compared to the combined councils. Al-Dabbash even stated the IAI were ‘not extreme like ISIS’, were ‘one of the biggest factions fighting’ and would accept ‘western military support to stop Maliki’.48

During the early summer months of 2014, operational partnerships continued to bear fruit, particularly as the Sunni movement gained momentum heading south through Kirkuk, Salahaddin and Diyala, towards the Baghdad belt areas. Two former Iraqi generals associated with both the JRTN and GMCIR were placed in strategic positions in Anbar and Salahaddin,49 and other militant factions including IAI, the MA and Ansar al-Islam, along with other tribal fighters, formed part of the offensive, securing areas from the government. As suggested by Hassan Hassan,50 it was a failure to politically engage these other non-ISIS forces during their period of formation that allowed for the more radical elements to emerge.

On 12 June 2014, ISIS executed what initially appeared to be hundreds of mostly Shi‘a army recruits from Camp Speicher near Tikrit, in Salahaddin province. More recent evidence has suggested that this number is closer to 1,700,51 emphasising the brutality and scale of ISIS violence but also affirming the sectarian trajectory of the conflict. With Iraq's military evidently weak, on 13 June 2014 Ali Sistani called upon all Shi‘a men who were able to do so to join the fight against ISIS, which led to the establishment of the Hashd al-Shabi, or popular movement. This was followed by rhetoric from al-Maliki on 17 June 2014, who evoked Shi‘a narratives when he called for a military campaign in Anbar, akin to ‘the followers of Hussein and the followers of Yazid’, a reference to a seventh-century defining Shi‘a battle. Such calls from Sistani and al-Maliki would only deepen sectarian grievances across the state. From this point, not only did Sunni communities have to contend with the government's forces, but also those of a popular Shi‘a movement that contained a number of prominent Shi‘a militias whose violent actions against Sunnis had been well documented during the mid- to late 2000s.

ISIS slowly gained control of the Sunni insurgent movement, but by the end of summer 2014 disagreements between it and other groups had intensified. In August 2014, the GMCIR accused ISIS of trying to hijack the ‘revolution’ following its attack on the Yazidi community near the northwestern town of Sinjar, which brought about international condemnation. Such actions precipitated the divide between ISIS and other insurgent groups, but this did not stop ISIS in their efforts to establish a caliphate. ISIS targeted dissonant Sunni factions and potential opposition, killing over 200 members of the Albu Nimr tribe as part of its attempts to establish authority in Anbar, during October 2014.52 This strategy, coupled with the threat of international reprisals, caused groups such as IAI, JRTN and MA to break ties with ISIS. In the case of MA, in August 2014, it refused to either pledge allegiance to ISIS leader al-Baghdadi or leave Karma (in east Anbar province), which led to ISIS kidnapping MA members, shelling and detonating the homes of MA members and even refusing tribal mediation.53 MA, like many of the other insurgent groups that were part of the initial offensive, either withdrew, fractured (many members even joining ISIS) or operated under the ISIS banner. ISIS were, however, able to pay salaries to their fighters through an intricate network of financing that included the sale of oil, taxation and the maintenance of local industry; this enticed many to join their ranks, a public relations opportunity ISIS was able to capitalise on. For instance, despite Ansar al-Islam openly rejecting ISIS's advances in Iraq, in August 2014 it was reported that 50 of its leaders had declared allegiance to ISIS, a statement that was rejected by Ansar al-Islam,54 and approximately 90 per cent of its fighters also joined ISIS.55 It is not known whether this claim was entirely true, and Ansar al-Islam have continued in some capacity to resist ISIS in the north of Iraq. It is likely, however, that they lost much of their strength following ISIS's gains in the summer of 2014.

Although ISIS gained control of much of the territory and the logistics routes that linked these territories following the 2014 offensive, opposition from a number of the factions still remains. Indeed, low-level fighting between the supporters of JRTN and ISIS is well documented in Kirkuk, with reports of attacks and reprisals by ISIS across the province. In one particular case on 1 December 2015 and in response to previous attacks, ISIS reportedly kidnapped 35 members belonging to JRTN and Ansar al-Islam in the south of Kirkuk province.56 It is likely that the fate of those kidnapped will be execution, consistent with ISIS's strategy of making its surrounding Sunni areas in Iraq subservient to its demands. Nevertheless, persisting resistance from other factions also shows a degree of disharmony and the potential for the development of a larger resistance movement, akin to the Sahwa. Sunni tribes and communities have little faith in the Iraqi government, though, and because of fears of retribution, working with the USA and other coalition forces will take time to develop, particularly to the level of synergy witnessed in the Kurdistan region, where a degree of unity amongst the Kurdish factions enabled a coordinated response against ISIS. Moreover, Shi‘a actors have also lost faith in the government, in part led by the Al Sadr, resulting in the storming of parliament on 30 April 2016.

The inability of the Iraqi government to confront ISIS as a unified entity is indicative of its fragmentation over a longer period of time. In addition, security failings were also furthered by a political system that had failed to provide the appropriate opportunities and mechanisms to allow for greater Sunni participation. By doing this ISIS has not only isolated a large bulk of its society, capable of aiding its development as a state, but contributed to the country's chaotic circumstances.

Failing Iraq and the security apparatus

As previously noted, the Sahwa programme generated short-term success but the political and sectarian issues that had helped drive the insurgency following the 2003 invasion were never truly resolved. Initial signs were positive; after all, the USA had agreed to withdraw by 2011 and inclusivity was aided by the drafting of Sunni Arabs from communities and tribes into the security forces, particularly in Anbar where the local and federal police forces were bolstered. Despite this, the majority of Iraq's Sunni Arab communities remained on the periphery.

From 2006 up to the summer of 2014, al-Maliki's own ambition, along with his power bargaining with hard-line Shi‘a nationals only managed to increase the schism between Sunni communities and the Shi‘a Dawa-dominated government. Much like under Saddam, patronage networks were built and loyalty was rewarded through governmental positions, benefiting a number of hard-line Shi‘a figures and Shi‘a militia members in particular. As a former member of the Iraqi intelligence service between 2007 and 2010 noted, ‘They [hard-line Shi‘a] wanted to control all functions of government, to protect their power and gain financially, but in doing this they undermined or removed experienced technocrats.’57

For example, Iraq's intelligence service was re-established in 2004 under US supervision. The Iraqi National Intelligence Service (INIS), as it became known, was first led by a former officer in Saddam's army, General Mohammed Shahwani, a Sunni Arab who had fled Iraq in the 1990s before becoming part of an attempted CIA-led coup against Saddam Hussein in 1996.58 In order to counter US influence and assert control, al-Maliki and the Dawa party sought to challenge the INIS, even creating a parallel intelligence network as part of the Ministry of State for National Security Affairs (MSNS).59 Shahwani retired from his position in 2009, reportedly in response to al-Maliki's misuse of intelligence leading up to ‘Black Wednesday’,60 when four large bombings in Baghdad by Sunni militants killed 183 people. Politicisation of the security sector has remained a theme and its inherent dysfunction was further aided by a political quota that has enabled the appointment of ‘incompetent individuals to leadership position on the basis of political loyalties rather than ability and national needs’.61 Drawing on Iraq's sectarian cleavages and internal power struggles, this process has entrenched mistrust between the various groups and, in doing so, removed the mechanisms needed for coordination and intelligence gathering in particular, causing a fundamental weakening in security, a legacy of al-Maliki's tenure that has proved difficult to overturn.

Favouritism and the buying of loyalties also affected the military. Experienced Sunni officers were removed from their high-ranking positions and replaced with Shi‘a commanders who were given authority to ‘run battalions, brigades, or divisions as personal fiefdoms extracting revenues from procurement deals or collecting “taxes” from subordinate ranks’.62 Iraq's military was already a skeleton of its former self and, in reality, international donors had no intention of investing in the creation of a strong force post-2003. Nevertheless, as part of the development programme, finances were made available. By 2012, the USA had made $US25.26 billion available to Iraq's government for the training, equipping and sustaining of the ISF, and for the infrastructure of the Ministry of Defence and Ministry of Interior.63 However, by 2008 both the police force and army were already finding it difficult to recruit and were witnessing an increasing number of members failing to turn up, with 3 per cent of the military absent without leave (AWOL) on a monthly basis.64 To counteract this trend, former Sunni officers were drafted in to make up for the 30 per cent depletion in leadership numbers, and while a small number of the thousands approached were given official positions, the majority that did sign up had no orders. A former Iraqi army general said ‘we were asked to attend work at an airbase in Baghdad, but it was soon very clear that it was all for show’.65

Iraq's military expenditure had more than doubled from 1.9 per cent of GDP in 2006 to 4.3 per cent in 2014, but the security sector in general was unprepared to deal with the assault. In response to these flaws, the new prime minister, Haider al-Abadi, set about purging the security sector of its corrupt and incapable officials, including many supporters of al-Maliki.66 Dozens of military commanders were removed from their posts and even the Minister of Interior, Adnan al-Asadi, was replaced. In December 2014, al-Abadi revealed 50,000 ‘ghost soldiers’ were still receiving salaries from the government despite not having any record of attendance. Many of these ghost soldiers were missing, deserters, retirees or dead, but the commanding officers had not removed their names from the payroll. According to Iraqi army sources, ‘The commanders did not report the real numbers to keep getting the [ghost soldiers’] salaries, so no one could do anything to stop the collapsing of troops at that time.’67 So when ISIS and its affiliates secured control of areas in Mosul and the provinces of Anbar and Salahaddin, this was because the ‘battalion or brigade has to have at least two-thirds of its boots on the ground to attack […] but because of the corrupted commanders, the fighting capability of the Iraqi troops was no more than 20 per cent’.68

By the summer of 2014, the security apparatus was much weaker than initially assumed and, as a consequence, was unable to respond to the ISIS-led summer offensive. Security forces were ill-equipped, untrained and unmotivated to deal with the situation, all the more obviously when compared to the response in the Kurdistan region from Kurdish forces despite their own political fractures. ISIS social media accounts and YouTube uploads captured evidence of their forces taking villages, towns and cities and, in some cases, ISF fleeing checkpoints and positions on roads and highways. Such videos helped to cultivate a climate of fear that would surround the group and increase perceptions of its military prowess. ISIS took security vehicles and stockpiles of military weapons along the way, accumulating an armoury and enough momentum to support a long-term struggle with the government of Iraq. What security forces remained were relatively small in number, limited in supplies and often without pay.

Sunni Arab tribal leaders and other political figures from within Sunni communities called for the government to arm their fighters to confront ISIS; however, both al-Maliki and al-Abadi showed reluctance to do so. Much of this was related to the way in which the second Sunni revolt emerged, where former Sahwa fighters and others who had supported the anti-AQI movement turned on the government and its security forces. Weapons were readily available and the Iraqi government had procured a considerable number of them. According to a local source from Ramadi, at the beginning of the revolt in 2012 ‘some groups (militant factions) were already buying up the weapons from the villages and towns’, adding, ‘You can't blame them; they needed the money’.69

In addition to this, documents seized by US forces in Mosul during 2010 also linked a number of senior Sunni political figures to ISIS,70 who at this point in time had established itself a network for smuggling and other illegal activities in Mosul. Some of the officials cited in these documents can be considered political opportunists, who also sought financial gain from the illegal activity of groups such as ISIS. For instance, following ISIS gaining control of Mosul, one such name was the former Ninawa province governor, Atheel al-Nujaifi71, who called for the devolution of power in Iraq and the creation of a Sunni Arab army to confront ISIS.72

While mistrust and corruption are evident, another reason affecting the government's support for a Sunni Arab army was the worsening economic conditions. With its finances dependent on the price of oil, which took a dramatic downturn during 2015, bottoming out at US$28 per barrel, the government has been forced to cut public expenditure significantly. In October 2015, an officer from a border crossing in Anbar and a federal police officer based in the western Anbar town of Haditha, a town which is constantly under attack from ISIS forces, declared they had not received their salaries for ‘six months’.73 Following the near collapse of Iraq's army in the summer of 2014, much of the funding available was diverted to the Hashd al-Shabi (or people's movement), the Shi‘a-dominated popular forces that were established under government supervision following Sistani's call to arms in June 2014. The Hashd are led by the pro-Iranian Badr organisation's leader, Hadi al-Ameri, who is deputised by leaders of prominent Shi‘a militias, Qais Khasali of Asaib al-Haq and Abu Mehdi Muhendis of Kataib Hezbollah.

The Hashd al-Shabi, which consists of people from predominately Shi‘a but also Sunni, Turkmen, Yazidi and even Christian communities, was established to defend Iraq, but most of its strength is drawn from the trained and more experienced pro-Iranian Shi‘a militias. A number of these groups, such as Asaib al-Haq (AAH)74 and Kataib Hezbollah (KH), have gained notoriety for their attacks against US forces post-2003, their confronting of Sunni militant organisations such as AQI and the sectarian targeting of Sunnis. In a growing trend since 2013, some Shi‘a militias are reported to be complicit in the ‘cleansing’ of mixed ethnic areas in Babil province, Diyala province and Baghdad, while claims of attacks against Sunnis have also been made in Kirkuk and Salahaddin province.75 This has included abductions, killings and extortion of Sunni individuals and families, a situation that has worsened since the summer of 2014.

Uncertainty in Iraq is indicative of its fragmentation, further fuelled by the inability of its government to provide security for its entire population across ethnic and sectarian divides. This has allowed forces at the radical end of the spectrum to fill the vacuum left by the weakened government, which, in turn, has itself looked towards the Shi‘a militias for support. In essence, this has resulted in the establishment of parallel security infrastructures, condoned by the state. This has created further mistrust in Iraq's Sunni Arab communities, where galvanised by political rhetoric from Shi‘a hard-liners and the actions of the Shi‘a militia, it has provided cause for the mobilisation of militant factions. Such conditions have allowed both AQI and ISIS to take advantage of the situation, once more perpetuating the sectarian schism and the fragmentation of Iraq. Without the appropriate curtailing of these political and ideological forces, even with the removal of ISIS militarily, the conditions for civil conflict and Sunni militancy will remain.

Enduring Sunni militancy

Groups such as ISIS do not represent the majority of Sunnis in Iraq, nor do Shi‘a militias represent the Shi‘a community. Yet in conditions where a weak government and uncertainty across both Shi‘a and Sunni communities is prevalent, the struggle for power and ensuing violence is likely to remain. The power vacuum has therefore allowed for the emergence of armed militant factions who wield considerable authority in their respective localities and, in the case of the Shi‘a militia in particular, at the national level, and often with impunity.

The role of the Shi‘a militias has proven pivotal in re-establishing government momentum against ISIS, but this success has come at a cost. A thirst for revenge for the loss of family and loved ones exists amongst the Shi‘a population and this has tended to feed the sectarian dimension of the struggle. In doing so, it has provided the more radical elements of the Hashd al-Shabi with justification for their actions, not just against militants but Sunni communities as well. There are stories of families in the predominantly Shi‘a south of the country demanding – and receiving – the heads of Sunni militants as reparation for the loss of family members in conflict, and war souvenirs are also increasingly common.76 Such issues will only serve to perpetuate the cycle of violence and the sectarian mistrust. The ‘cleansing’ of areas by Shi‘a militias is unlikely to have a positive sustainable impact on the security situation across the state, as witnessed in the mixed sectarian provinces of Babil and Diyala.

Since 2003 the security conditions in the north of Babil province have caused problems for first the occupying forces and subsequently the Iraqi government. As a former Baathist stronghold directly south of Baghdad, the area became synonymous with its pockets of resistance and vibrant Sunni militancy, earning the label ‘Triangle of Death’ from the US military. Its predominately Sunni population has suffered from the same political and socio-economic conditions that engulfed many other Sunni areas following the removal of Saddam Hussein. Factoring in its past, this has increased its susceptibility to radical elements of Sunni Islam, such as AQI, as it did in presenting itself as an ideal location for ISIS to embed its core fighting forces, an event that eventually justified a full-scale Iraqi security force and Hashd al-Shabi (albeit mostly established Shi‘a militia) operation in October 2014.

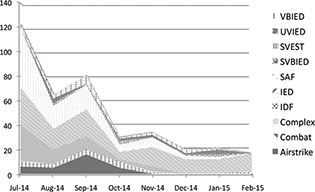

The deployment of Shi‘a militias into northern Babil was a hugely controversial move, yet despite this, it led to the removal of ISIS's core fighting force by the end of October 2014. Nevertheless, as a consequence of these actions, Sunni Arab communities were systematically removed from their land, causing an increase in the number of internally displaced persons (IDP), placing an increasing economic burden on the state and ultimately causing greater uncertainty across the region. Through the creation of these conditions, the government has become complicit in the proliferation of sectarian tension, explored in more detail in Chapter 5. As the following statistics highlight (Graph 5.1), even after the expansion of ISIS in the summer of 2014 and the subsequent government-militia security operations in the autumn of the same year that removed ISIS's main force, statistics indicate that Sunni militant activity remained in the early months of 2015, albeit low-level asymmetric activity, which nonetheless questions the limits of the clearance strategy.

Graph 5.1 Number of incidents in Babil province between July 2014 and February 2015. (The thickness of the line denotes the actual number of a particular type of attack relative to the number of incidents in total.)77

The security operations in the north of Babil were successful in that they removed ISIS as a core fighting force, and over time reduced logistic routes into the capital Baghdad. Statistics also show a marked improvement in security when comparing the current situation to the period between July and October 2014. This is, of course, related to the end of security operations, and the reduction in combat and other attacks such as airstrikes, mortars and artillery rockets (commonly known as indirect fire or IDF) and small arms fire (SAF). Incidents reported therefore decreased from 123 in July 2014 to 17 in February 2015 (see Graph 5.1).

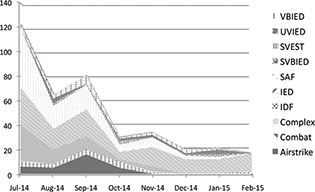

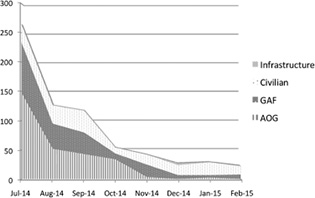

Nevertheless, despite the reduction in conventional warlike methods, an asymmetric threat has persisted, affecting the lives of the remaining provincial population. Shi‘a Arab civilians, Shi‘a militia and security forces in what were predominately Sunni but mixed areas like Jurf al-Sakhar, Latifiya, Iskandariya, Yousifia and Mahmudiya continue to be targeted on a consistent basis by improvised explosive devices (IEDs).78 Indeed, on reviewing the statistical information we can see that IED attacks have remained at a relatively high rate since August 2014 when security operations began, becoming the main form of attack following the end of the more conventional form of fighting. This suggests that Sunni militancy continued despite the removal of ISIS's core fighting force. Secondly, on viewing the data collected in Graph 5.2, it reveals that the targeting of civilians has also remained constant since the end of the government-militia security operations in the province during November 2014.79 This is particularly evident when compared to the targeting of Sunni militants (marked AOG) and government aligned forces (marked GAF). Between November and February, civilians were targeted; 17, 17, 22 and 15 times respectively.

Graph 5.2 Attack targets and estimated casualty numbers during the period July 2014 to February 2015. (The thickness of the line denotes the number of a particular target casualty relative to the number of attacks in total.)80

The cleansing of areas in northern Babil had a significant impact upon Sunni communities in both the province and across Iraq, adding to the insecurity in the longer term. Evidence of the damage caused can be seen in Jurf al-Sakhar, a predominately Sunni town in northern Babil that bore the brunt of government-militia security operations.

Jurf al-Sakhar,81 like most of its surrounding areas, is known for its historical links to the Baath party but, after 2003, to Sunni militancy. Its location, approximately 35 km south of Baghdad's city parameters on the banks of the Euphrates and 30 km northeast of the city of Karbala, makes it a strategically important area for the launching of attacks against government and Shi‘a interests. Following the expansion of ISIS's main fighting force into Iraq, Jurf al-Sakhar became a natural stronghold.

Government forces had made a number of efforts to take control of the town dating back as far as 2013, forcing a majority of the 80,000 residents to flee. By the end of October, government and militia forces had established control. This involved the total clearing of the town and surrounding rural areas, leading to the confiscation of land and the separation of families. Women and children were placed in compounds while the fate of a number of their men has not yet been determined. According to an Iraqi security spokesperson, the ‘families were harbouring Islamic State […] The judicial system will decide their fate.’82 Unfortunately, the reality has not been as transparent. The distinction between ‘Jihadi’ and ‘Sunni’ became blurred amidst the security operations, and reports of militias Asa'ib Ahl al-Haq and Kataib Hezbollah active in the area,83 and it is likely that a blanket security policy became the norm. Jurf al-Sakhar remains dormant, its buildings destroyed and emptied. In addition to this, despite initial indications from the government that those with no ties to Sunni militants would be allowed to return to their land, it has still not happened. It has even been mooted that the area may be used as a forward operating base for future offensives in Anbar.

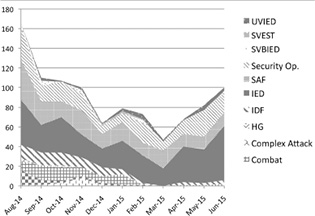

A similar pattern of violence emerged in Diyala province in the summer of 2014, when a small number of its Sunni Arab villages and towns came under the influence of ISIS and other affiliated groups. Following clearance operations, which peaked in November 2014, both incident numbers and the scale of attack decreased. However, following this relative success and the redeployment of some security forces to other combat areas, asymmetric attacks, particularly IEDs, have persistently targeted Shi‘a Arabs and security forces and since March 2015 there has been a notable increase in the level of violent attacks.

Looking at Graph 5.3, the data between August 2014 and June 2015 reveals a trend that only asymmetric violence increased and violence intensified, thus suggesting a return to the conditions witnessed in the summer of 2014. This potentially opens the door to high-impact attacks and an escalation of violence between both Shi‘a and Sunni Arab communities, as witnessed on 17 July in the southwest of Diyala province, when a suicide vehicle attack (SVBIED) in a market area of Khan Bani Saad, in the largely Shi‘a populated district of Baquba, killed at least 100 people and injured many more during an Eid gathering.84

Graph 5.3 Number of incidents in Babil province between August 2014 and June 2015. (The thickness of the line denotes the actual number of a particular type of attack relative to the number of incidents in total.)85

Diyala province is a flashpoint area, given its mixed Shi‘a and Sunni population. Since late summer 2014, Shi‘a militias have maintained a strong presence in Diyala, which Human Rights Watch suggests has led to an increase in kidnappings, execution-style killings and the forced removal of Sunni populations.86 In Muqdadiyah alone, which is in the centre of the province just east of the River Diyala, Human Rights Watch states that at least 3,000 (mostly Sunnis) fled their homes following June 2014, many of whom have since been unable to return. One person declared that ‘when we tried to return home, our house was being used by somebody else. We are sure they are a Shi‘a family, but what can we do? The government is not on our side.’87

A local police officer working in the area also said, ‘many Sunnis have lost their homes, but some have fought back, sometimes with guns and sometimes using roadside bombs and placing bombs outside of buildings. Most of them are not Daesh, but they are desperate.’88

While we cannot be sure about the specific number of attacks in Diyala that are linked to ISIS, a number of the attacks are conducted by locals and driven by local issues. This again has the potential to form part of something much bigger, to become part of the larger struggle that continues to be proliferated by the extreme sectarian elements. Throughout 2015, retaliatory attacks continued and in January 2016 the escalation of violence caused Sistani to condemn the activity of Shi‘a militias acting outside the law, while Prime Minister al-Abadi called for calm.89 However, with both a weak government and the pro-Iranian Badr and militia Asaib al-Haq maintaining a strong presence in Diyala, any peaceful resolution would have to include the involvement or acquiescence of the latter two, an issue unlikely to be supported by the Sunni communities at large.

The long-term threat of Sunni militancy

While Sunni communities have been targeted in an effort to remove the threat of ISIS, this has also served as a pretext for the more radical elements of the Shi‘a militia to assert their power in the state. As the previous statistics have shown, such strategies have failed to enhance human security, as asymmetric attacks persist in and around the areas that have been targeted as part of government-militia operations. Policies that continue to cause the displacement of people or cultivate fear are therefore unlikely to reduce militant activity beyond the removal of ISIS and other related groups as a core fighting force. Events similar to those witnessed in northern Babil and Diyala have also been evident in other provinces across Iraq, even Sunni majority provinces such as Anbar and Salahaddin. For example, following the involvement of Shi‘a militia in areas such as Habbaniyah, Husaybah and Khaldiyah in Anbar province during the first quarter of 2015, a number of incidents involving the looting and blowing-up of Sunni Arab homes were reported. A police officer from Anbar was quoted saying, ‘These militias broke into empty homes and stole cars. In one example, my cousin's car was stolen from his house, and later reported in Baghdad, where it was being sold.’90

Financial profiteering in an environment of such economic insecurity is also fuelling crime and sectarian tensions. An Iraqi journalist in Baghdad added to this: ‘In Sadr City, there is a market under a bridge that people call “Daesh” market (Souk al-Daash). On the market they sell cars, electrical and other consumer items stolen from Sunni houses in Baghdad and from other provinces.’91

In the north of Iraq, similar concerns have been raised regarding Sunni Arab communities near ISIS strongholds Hawija and Mosul, particularly as Kurdish92 forces consolidate and advance their own regional borders that cut across Ninawa, Kirkuk and (north) Diyala provinces. The situation in the north is even more fluid as it draws national, ethnic and sectarian cleavages into the struggle within the context of the fight for Kurdish autonomy.

Since August 2014, reports have documented the establishment of ‘security zones’ by Kurdish forces to hold Sunni Arabs displaced from areas near the Kurdistan regional border in the conflict with ISIS.93 Amnesty International has also reported the displacement of thousands of Sunni Arabs and destruction of numerous villages previously populated by Sunni Arabs.94 Even in the Yazidi95 majority town of Sinjar in Ninawa, close to the Syrian border, tensions have escalated following the removal of ISIS by Kurdish-led forces in November 2015. Kurdistan region president and leader of the KDP, Masoud Barzani, had his Peshmerga forces lead the assault, but they were also joined by rival Kurdish factions the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) and its Yazidi and Syrian Kurdish affiliates known as the Sinjar Resistance Units (YBS) and People's Protection Units (YPG) respectively.96

According to one Yazidi fighter known as Mr Ceedo, ISIS ‘took the honour of Yazidis’ and, referring to Sunni Arabs in general, there was ‘no way’ they would be welcomed back.97 The suffering of the Yazidi community at the hands of ISIS has led to retribution and blaming of Sunni Arabs for ISIS's discretions. This hostility is highlighted in a personal account of a Sunni Arab male reported by Amnesty International:

After the Peshmerga and the Yezidis and the PKK recaptured the area in December 2014 we were told by Peshmerga officers that we would be able to go back home within a few days. But then we started to hear that Yezidis and PKK militias were staying in our village and would attack any Arabs who went there […] A few days later our village was burned down. Three weeks later the Yezidis and the PKK burned several other villages nearby and killed several villagers.98

Such actions against Sunni communities are unlikely to herald stability, and could even contribute to sustained acts of violence, as shown in Diyala and Babil provinces. As highlighted by an aid worker in Sinjar, ‘Now the Yazidis have become just like Daesh […] If our rights will not be given back, we will fight them.’99

Under Barzani, the Kurdistan region has assumed responsibility for the security of Sinjar and its surrounding villages and towns. Controlling this area allows them to monitor logistical routes used by ISIS, but it also broadens the borders of the Kurdistan region. Despite their own internal political schisms, the Kurdish regional government has used the weakening of Iraq's sovereignty following ISIS advancements to assert its control over its border areas, thus strengthening its claim for independence. In the long term, this is likely to trigger a response not only from Sunni Arabs, but Shi‘a Arabs and Turkmen as well, a microcosm of which is being played out in the mixed ethnic and sectarian province of Kirkuk.

Iraq's complexities are highlighted in the provincial border between Salahaddin and Kirkuk, where despite the existence of an anti-ISIS alignment, tensions between Sunni Arabs, Turkmen of both Shi‘a and Sunni faith, and Kurds continue to typify the country's historical creation and current fragmentation. In Tuz Khurmatu on 12 November 2015, low-scale fighting erupted between Kurds and Shi‘a Turkmen as local disagreements over property and land led to the targeting of one another, the burning of shops and the involvement of both Kurdish Peshmerga forces and Shi‘a militias. As noted by Adnan Abu Zeed, the disruption to this area which had remained relatively calm between 2003 and 2014, was caused by the withdrawal of Iraq's security forces from northern areas following the summer of 2014 and the subsequent land grab by Kurdish forces,100 who claim their historical roots in the area of Tuz Khurmatu.

***

As this chapter has shown, Sunni militancy and the emergence of groups such as ISIS in Iraq is a symptom of the conditions that have been created, where sovereignty has slowly eroded and fragmentation of the state increased. These issues themselves are part of a dynamic historical process that has included international intervention, tribal relations and sectarian differences amongst many other interactive layers of overlapping influences. This chapter has also sought to highlight that stability in the region cannot be enhanced through land grabs or the targeting of particular ethnic or religious groups. As the statistics in the mixed Sunni–Shi‘a Arab provinces have shown, strategies that have attempted to remove the threat of militancy through the cleansing of Sunni Arab majority areas have failed to enhance human security, as asymmetric attacks persist in and around the areas that were targeted. Policies that continue to cause the displacement of people or contribute to generating fear are therefore unlikely to reduce militant activity beyond the removal of ISIS as a core fighting force, and this should also be taken into account in the northern areas, where Kurdish forces have sought to take advantage of Iraq's fragmentation. Uncertainty, particularly in Sunni Arab majority areas and provinces, can be alleviated by projections of prosperity and access to decision-making processes. However, this will require considerable political and economic concessions and ultimately greater regional autonomy, which in creating a more stable environment could lead to further fragmentation.