Ancestry.com’s general search form will comb through the site’s millions of records, though the number of results may overwhelm you.

Nearly all of my ancestors resided in the Pennsylvania German heartland of Berks County in 1850. So one of my first genealogical acts after becoming engrossed in the hobby in the mid-1980s was seeking out the microfilms of the 1850 US census and seizing what turned out to be three films for Berks at the nearest repository where I was living at the time.

I recall spending eight hours and getting “microfilm reader elbow” from scrolling through just that trio of films and copying down the couple dozen direct-line ancestral families I had found—though I admit that it took longer because I didn’t know how to use the coding that a local society had produced! It was a wonderfully exciting but exhausting day—but who would access the census that way in the present? Just as a test, I found and printed out those same family records in just fifty-three minutes using the Ancestry.com search engine <search.ancestry.com> as an index.

A subscription to Ancestry.com <www.ancestry.com> is an essential component of any German genealogist’s research regimen. Yes, the site has limitations and some shortfalls to bear in mind, and we’ll point these out in this chapter. But on balance, it’s not a close call to say that, with the price of its highest-end subscription still about a buck a day when paid annually, Ancestry.com is one of the genealogy world’s true bargains. Without the investment made by its original founding partners and subscribers to Ancestry.com over the years, considerably fewer (if any) records would be available to genealogists on the Internet. And when you factor in the time and transportation savings when comparing using the site to going to repositories or trying to use only free sites, it’s hard to argue that Ancestry doesn’t pay for itself—and then some.

In this chapter, we’ll review some basics about Ancestry.com, school you in what comes free of charge on the site (including a valuable pre-WWI German gazetteer), go through Ancestry.com’s voluminous grab bag of German genealogy content, and also mention some of the goodies on Ancestry.com sister sites such as Newspapers.com <www.newspapers.com>, Fold3 <www.fold3.com>, and the venerable RootsWeb <www.rootsweb.ancestry.com>. For more detail about Ancestry.com and how to use it, see the Unofficial Guide to Ancestry.com by Nancy Hendrickson (Family Tree Books, 2014) <www.shopfamilytree.com/unofficial-guide-to-ancestry>.

Take care when using the Match Exactly tool on Ancestry.com’s search forms. Searching on first and middle names with exact matches only can miss records that list Rufnamen (“prefix” names that are seldom used later in life—see chapter 1).

As far as size and complexity, Ancestry.com is another monolith of a website like FamilySearch.org <www.familysearch.org>, which we discussed in chapter 4. A lot of the similarity ends at that point, however, since Ancestry.com is a for-profit company (though it’s gone through various business structures in its existence). And while it has made considerable attempts at helping the largely nonprofit genealogy community, it is a business, and some of its moves over the years have been decidedly less than friendly to some segments of the genealogy world.

Ancestry.com offers three different membership levels, and the Unofficial Guide goes into detail about them. For this book’s purposes, you need to know the following: You can access the free items and create a family tree on Ancestry.com by registering (for free) as an Ancestry Member, but you’ll need to have the World Explorer or All Access membership to access some of the German records referred to here. You can learn about the three tiers of paid subscription service online <www.ancestry.com/cs/offers/subscribe?sub=1>. Ancestry.com occasionally runs fourteen-day free trials of its memberships, a great way to get acquainted with the site and its value before investing more time and money. You can also receive a discounted plan if you pay semiannually rather than monthly, and AARP members receive a one-time discount.

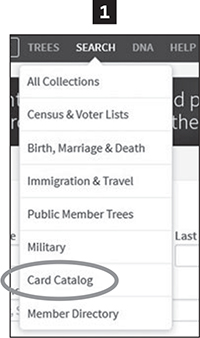

In addition to being able to select from different tiers of membership plans, you can choose which elements will appear on your Ancestry.com home page to suit your research needs. Across the top of your screen, you’ll see a menu with six broad categories. Home takes you to your Ancestry.com home page, which you can customize, and you can create, manage, or upload your own family tree in Trees. You’ll likely spend most of your time on the site in Search, which gives you a submenu of general record categories that will be detailed later. For those interested in genetic genealogy or who have taken a DNA test, DNA takes you into the burgeoning AncestryDNA arm of the company <dna.ancestry.com>. The Help submenu contains links to the Support Center (for technical questions) and the Learning Center, which includes downloadable research guides. Under Help, you can also access Community and Message Boards to collaborate with other Ancestry.com users and the World Archives Project, an ongoing project dedicated to indexing all records. Finally, Extras includes links to download Ancestry.com apps for iOS and Android, create and order photo projects, browse Ancestry Academy (a collection of video courses), and buy gift subscriptions. You can connect with ProGenealogists (professional researchers who work for hire) under both tabs: Hire an Expert under Help and ProGenealogists under Extras.

As stated earlier, most of the heavy lumber for German genealogists will be found under the Search tab. If you just click on Search, you’ll arrive at a generic search form (image A.) for you to fill out, though an advanced search form is available, too. While you’ll eventually dig deeper into individual records collections, you’ll want to run your ancestors through this as a starting point. If you just click on the Search tab, you’ll find a list of record collections (categories of similar records consisting of many individual Ancestry.com databases) and other searchable data that includes:

Ancestry.com’s general search form will comb through the site’s millions of records, though the number of results may overwhelm you.

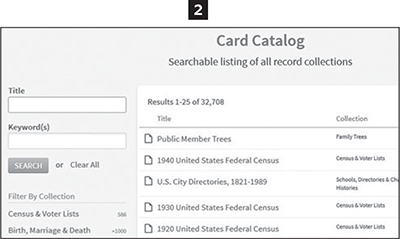

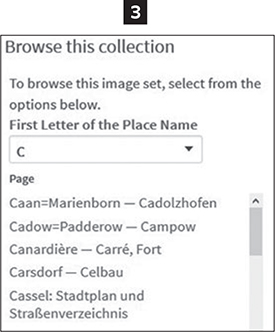

Back to the Card Catalog for a moment. The Card Catalog is a key part of Ancestry.com for two reasons. While it’s not quite like the local library card catalogs of an earlier day—it’s not the old trio of subject, title, and author headings—it’s a way to seek out specific databases or databases with particular information. Secondly, it’s your entrée into browsing digitized images of the specific databases.

Instead of subject, title, and author headings, the Ancestry.com Card Catalog has two prime search boxes. First, there’s Title, which as you might expect will return databases with a particular word in the title (you can use an asterisk to substitute for letters—for instance, German* will come back with results for databases with either Germany or German in the title). Secondly, there’s Keyword(s), which can be part of the title but are also drawn from metadata describing the database and therefore are broader (asterisks can be used here, too, to widen the search). Once you’ve done a search, you’ll also see other filters available—by collection, by location, by dates, or by languages—if you want to narrow the number of databases further.

There’s no one magic title or keyword, however, that gets you all the German genealogy resources at once; for example, the German* title and keyword searches do successfully pick up a number of the Ancestry.com databases for church records of ethnic German congregations in America, but not all of them. You’ll also want to do searches for names of specific villages and German states if you are searching individual databases (though again, you should first do a global search of all the site’s databases from the main Search tab—searching more narrowly in databases will help you whittle down that unwieldy number of results). Unlike FamilySearch.org’s consistent use of the states of Second German Empire to label villages (see chapter 4), Ancestry.com’s catalog sometimes uses state names and other times does not.

For pretty much anything you find on Ancestry.com, you’ll have the opportunity to send it to a shoebox as part of your customized Ancestry site or download the record (or book page, or whatever) to your own computer. You’ll also find that when you do global searches on Ancestry.com or start a family tree on the site, the site will try to help you out by offering shaking leaf icons (hints) that show records that may relate to the same individual. The shaking leaves should be used with caution; sometimes they can be a great research shortcut, but other times they will only relate to your ancestor because they have a similar name.

Though there’s no doubt that Ancestry.com’s worth any serious German genealogist’s subscription dollars, some substantial resources are available merely by registering for free as an Ancestry Member. These freebies include the pre-WWI Meyers Gazetteer of the German Empire <search.ancestry.com/search/db.aspx?dbid=1074> that is so useful for finding data on German villages, plus several worthwhile emigration databases as well as indexes to some records and even a database of historical postcards. Several of these items deserve a more detailed look.

Ancestry’s Card Catalog calls it the Meyers Gazetteer of the German Empire, but naturally the Germans have a longer name for it: Meyers Orts- und Verkehrs-Lexikon des Deutschen Reichs. No matter what name you give it, this research tool is indispensable to German genealogists because it was published in the early 1900s, during the Second German Empire period (1871–1918) when Germany encompassed its great peacetime territory.

In addition to containing hundreds of thousands of entries as a geographical dictionary, Meyers includes loads of information about the places included: the state and district to which it belongs; whether it had its own civil registration office (or where its vital records were registered if not); population; court and military district data; businesses and industries; and whether there were churches in the town (and of what denomination). This is a case where the language skills that previous chapters have encouraged become helpful; of course, Meyers is in German and also printed in the difficult-to-read Fraktur font. You’ll also likely want to invest in a copy of the late Wendy K. Uncapher’s still-in-print monograph How to Read & Understand Meyers Orts- und Verkehrs-Lexikon des Deutschen Reichs (Origins, 2003) to help understand the heavily abbreviated listings of the villages.

Be wary of the geographic designations on the scanned pages in databases (both German and American). Some reflect mistaken and misspelled names in the originals; other errors may have been introduced when metadata was added.

A good number of the Ancestry.com freebies for German genealogists are merely indexes of collections, which makes sense from a business standpoint; if you want to access the original records, you’ll have to ante up. But the impressive thing is that these are a first-class tease, since the indexes the site includes are for some substantial emigration indexes from a couple of German states as well as some marriages and the seldom-seen helpful German state censuses. Among the databases that have free indexes are the following:

In some cases, the actual records in the Ancestry databases are free for the taking. Significant such databases include:

In addition, Ancestry.com has made a number of databases dealing with the German death camps and deportations of Jews from Germany during the WWII era free.

The Hamburg Embarkation Lists and their Handwritten Indexes are two separate databases that Ancestry has obtained from the state archives of Hamburg. Here’s a chronology of the lists and handwritten indexes and what’s available for searching and browsing:

| 1850 | Embarkation lists begin, initially just with names of passengers (first names often just had an initial) but later with additional details. Ancestry.com has also made available images for the entire extant run of lists. |

| 1855 | Handwritten indexes begin. Because the database is an index, these are not searchable on Ancestry.com and are only browsable. |

| 1854–1910 | The lists and handwritten indexes are separated into “direct” (passengers who weren’t going to change ships before their ultimate arrivals) and “indirect” (those who did change ships). |

| 1911 | Lists are no longer separated into “direct” and “indirect.” |

| 1915–1919 | No lists are kept during World War I. |

| 1934 | Lists and indexes from the port of Hamburg are no longer produced. |

Naturally enough, which of Ancestry.com’s assets are considered “major” for German genealogy is in the eye of the beholder; value, to some extent, is going to depend on whether your ancestors are found in a particular record set. Still and all, plenty of databases are unique to Ancestry.com, covering a multitude of times and places. Only the rare German researcher would be unable to find databases to mine, especially when you take into consideration databases including church records of ethnic Germans in America.

Another criterion is whether an asset can be found somewhere else on the Internet (especially if it’s for free on FamilySearch.org). The best examples are the huge databases of German births, marriages, and deaths. These include millions of records—but they are the same databases compiled by FamilySearch. (Interestingly enough, when Ancestry.com counts the “records” for each of these megadatabases, it comes up with three times as many as FamilySearch.org, presumably because the site segments the pieces of data included in the database’s documents in a different way.) Likewise, Ancestry.com has a couple dozen databases that FamilySearch.org designates as “miscellaneous city records” that are also duplicated on Ancestry.com because of the two groups’ partnership.

But while the caveat to look for content first on FamilySearch.org is valid enough, Ancestry.com has a bunch of intriguing databases that you won’t find there (or anywhere else, for that matter). This is where the rubber hits the road for Ancestry.com and the German genealogist—or perhaps a better metaphor is where the “ship hits the water,” since the number one marquee item is the Hamburg Embarkation Lists and their manuscript indexes.

Because of the potential for the search engine indexes to be wrong, consider browsing databases for a relevant time period instead of relying only on name searches.

The star attractions of Ancestry.com’s major assets are the records of emigration departures from the German port of Hamburg, which was the number two exit point from the European continent in the 1800s. About five million people left from Hamburg between 1850 and 1934 (the years that records were kept for), and about a third of those who left from Hamburg were from the German states. The remainder were from other areas, primarily eastern Europe, including many from the Russian Empire as well as Austria-Hungary.

You’ll want to check out two specific databases if you have ancestors who left Europe in the second half of the 1800s or early in the 1900s: Hamburg Passenger Lists, 1850–1934 <search.ancestry.com/search/db.aspx?dbid=1068> and Hamburg Passenger Lists, Handwritten Indexes, 1855–1934 <search.ancestry.com/search/db.aspx?dbid=1166>.

While the database with images of the actual lists is searchable for the years 1850 to 1923 (the entire run of images is available), bad handwriting creates a hide-and-seek game in which you may not be able to find who you’re looking for even with creative searches. In that case, you’ll want to browse the database of handwritten indexes in an attempt to find the name you’re looking for, then find it in the actual lists. You’ll either need to have a focused time period—or a lot of time on your hands!—since the handwritten indexes are segmented chronologically and then further broken up just by first letter of the last name. A further wrinkle is that for a portion of their run, the lists were divided into “direct” (passengers staying on the same ship to their ultimate arrival port) and “indirect” (those switching ships, usually somewhere in the British Isles).

Ancestry.com has digitized an enormous database of millions of records (almost eleven million using Ancestry.com’s math) that includes many church records relevant to those researching “first wave” (Colonial era) Germans in the Mid-Atlantic states, called Pennsylvania and New Jersey, Church and Town Records, 1708–1985 <search.ancestry.com/search/db.aspx?dbid=2451>. Most of the eighteenth-century records in this collection focus on baptisms, marriages, and burials, though a few other types of records such as confirmations are available for some congregations.

These records primarily come from microfilms in the custody of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP) <www.hsp.org>. And many of these were acquired due to the HSP’s relationship with the Genealogical Society of Pennsylvania <genpa.org>. In addition to original church registers, this database also includes many transcriptions of cemetery tombstone inscriptions and is both searchable and browsable on Ancestry.com. The browse function allows you to drill down first by county, then “city” (which sometimes needs to be massaged because many of these are country churches), and finally denomination (religious group) and name of the specific church.

What the HSP collection is for the “first wavers,” the records of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America are to the “second wave” Germans, many of whom settled in the American Midwest. The database is called U.S., Evangelical Lutheran Church of America, Records, 1875–1940 <search.ancestry.com/search/db.aspx?dbid=60722>, and contains more membership lists, records of communion, and treasures’ reports in addition to the “big three” (baptism, marriage, burial) records. Like the HSP collection, this database is both searchable and browsable. When browsing, you can view records by state, then city and specific congregation (in larger cities where there was more than one Lutheran church).

The powerhouse database titled Brandenburg, Germany, Transcripts of Church Records, 1700–1874 <search.ancestry.com/search/db.aspx?dbid=2116>, contains records from hundreds of parishes in the old Prussian heartland of Brandenburg, which overlaps but does not exactly correspond with the current German Land by that name—indeed, historic Brandenburg includes some areas now in Poland, a difficult-to-research area. Most of the records are from Evangelisch congregations, although some Roman Catholic and “Old Lutheran” records are also included. The source information attached to the database also gives a complete list of the parishes—as well as the names of all the villages included in those parishes—as part of the source information. The database is both searchable and browsable.

The database Ansbach, Germany, Lutheran Parish Register Extracts, 1550–1920 <search.ancestry.com/search/db.aspx?dbid=60913>, is similar to the Brandenburg collection in that it does not contain original church records, but, in many cases, is easier to read than the original set of records. The extracts on Ancestry.com are searchable and browsable. The Ansbach district’s original records are part of the Protestant church record supersite Archion <archion.de>, which will be profiled in chapter 8.

The databases for Ancestry.com’s German vital registers of births, marriages, and deaths might have multiple villages’ records but only be named for the city that is the seat of a district. For instance Rehna, Germany, Births, 1876–1899, which is now in the German Land Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, includes births not only from Rehna but also from the registry offices in the towns of Carlow, Demern, Schlagsdorf, Grambow, and Utecht. If you’re struggling to find records from your ancestor’s hometown, look for collections from nearby towns and villages that might have the records.

Ancestry.com has a geographically scattered but growing number of databases with digitized civil registers of births, marriages, and deaths, usually up to the current blackout periods mandated by German law. The areas included in the database are some of Germany’s largest and most historic cities (Berlin, Dresden, Mannheim, and Mainz, for example), as well as districts in both western and eastern Germany, ranging from Bavaria to the Palatinate to Lower Saxony to Pomerania. You can search for these individual databases by using the Ancestry.com Card Catalog.

Ancestry.com has other collections of records that don’t fit into a neat category, but it’s still important to know what to expect from these databases and where they come from. Over the years, Ancestry.com has added searchable scans of many “core collection” books as databases, including such standards as Pennsylvania German Pioneers, edited by Ralph B. Strassburger and William J. Hinke (Pennsylvania German Society, 1934)—though, interestingly, it breaks the books of this two-volume publication into separate databases.

Some databases, especially those Ancestry.com added years ago, do not include scans of the original books and therefore can only be name searched. These collections have undergone optical character recognition, or OCR, which makes them keyword searchable. For example, while Pennsylvania German Pioneers includes a scanned copy of the original book (image B.), other resources like New Jersey German Reformed Church Records, 1763–1802 <search.ancestry.com/search/db.aspx?dbid=3315>, which was originally published in print form, only has an OCR version (image C.).

Having imaged records allows you to survey the original document for contextual information or botched transcriptions.

Some collections on Ancestry.com are indexed but do not have images of the original record. While indexed records can be keyword searched, you may miss out on important information by viewing records without their accompanying images.

Of course, other major record groups—such as the US census and the National Archives Passenger Arrival Lists—are no longer unique to Ancestry.com but are standards for research no matter what a person’s ethnicity is. Record groups like these are covered in more detail in the Unofficial Guide to Ancestry.com.

In addition to looking directly for records on Ancestry.com, you can also take advantage of other users’ work. Many users make their family trees publicly available on the site to share their research with others. Public member trees that have been compiled by Ancestry.com members have good qualities, too: Many have been made, and as Ancestry.com makes its interfaces more sophisticated, users have better and better ways to add bibliographic sources to the individuals on their trees and link to the actual records.

Of course, making such tools available and having members actually use them are two different things. Remember that phrase “huge echo chamber of unverified information” from chapter 2? Well, that’s true here as well. No Ancestry.com users have to qualify their information when creating public member trees, and so you should always verify information you find here before adding it to your own research.

The benefit of this setup is less stress for users of Ancestry.com’s family trees than users of FamilySearch’s Family Tree might experience, as Ancestry.com will not attempt to merge individuals’ profiles, and other members can’t edit your Ancestry.com family tree. While this prevents genealogical range wars between two researchers with different views about what records relate to a particular individual, this leaves a large pool of flotsam and jetsam bobbling around: references to what appears to be the same individual duplicated in many family trees from the same tenuous or even nonexistent information.

But once again, this is not a recommendation to avoid using the public member trees on Ancestry.com, only an admonition to use them carefully. They provide potential research clues that can be invaluable time savers.

Of course, the folks behind Ancestry.com own many other properties. Some of these other arms are separate subscription services (such as Newspapers.com and Fold3) while others are essentially nonprofit properties that Ancestry has bought and continued to prop up (such as RootsWeb and Find A Grave <www.findagrave.com>). As usual, you can look to the Unofficial Guide to Ancestry.com for more details on some of the other sites and businesses in the Ancestry.com portfolio. We should point out some features of the sister sites that will be useful to the German genealogist.

Perhaps the most notable offshoot of Ancestry.com is AncestryDNA, one of the few companies that offers genealogically useful DNA testing. Going into the details of DNA is beyond this book’s scope, but the general concept is that when significant portions of two individuals’ DNA overlap, it indicates some sort of relationship between the two people. Genealogical brick walls can come tumbling down when this overlapping DNA between two or more people is combined with the paper documentation of the individuals. While DNA projects can also reveal that someone’s legal father wasn’t really his genetic father, these projects can also help the participants ferret out changes in spellings of surnames. For example, a descendant with the name Grass whose ancestor was thought to use that name (or Gross instead) found herself genetically related to Kress families in Germany.

Newspapers.com and Fold3 are two other arms of Ancestry.com, though they’ll cost you extra if you don’t have an All Access membership with Ancestry.com. Newspapers.com is exactly as its name implies—a collection of digitized, searchable historical newspapers from all across America. While the service has not emphasized acquiring German-language newspapers, it does have some of them that were included with other, larger collections. Unfortunately, there’s no way to search just for German-language newspapers, but you can drill down from the nearly four thousand titles that Newspapers.com has in its portfolio by going to its All Newspapers page <www.newspapers.com/papers> and using the tools on the left side of the page to narrow the list. You could, for example, search for a newspaper by name and include the German articles for the—Der, Die, Das—and other words typically used in German newspaper titles (Tägelich for “daily,” Wochen- for “weekly”, etc.).

Fold3, on the other hand, specializes in American military records, and one of its hallmarks is allowing users to annotate records when they have more information about individuals who are mentioned. Fold3 has digital copies of the full Revolutionary War pension files, which sometimes contain detailed information in the affidavits files by the former soldiers seeking benefits.

RootsWeb was the first genealogy megasite and remains free to users since its acquisition by Ancestry.com. Here, you’ll find oodles of family message boards as well as the impromptu home pages for some local genealogy groups and family associations that don’t have their own websites. RootsWeb, too, has many educational articles as well as various databases. You can find a directory of them on the German RootsWeb landing page <www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~wggerman>. One resource of interest to German researchers is a gazetteer of Alsace, an area that is currently French but was historically German <www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~fraalsac/alsaceaz/geninfoeng.htm>.

Ancestry.com says, “Acquiring German records is a large focus for Ancestry at this time,” and there’s no doubt the company means it. Ancestry.com is pursuing deals with German archives and continuing its partnership with FamilySearch.org. Ancestry.com’s expertise has won it contracts around the world, including those giving the site more American records in categories that may help German genealogists find references to ancestors’ European hometowns.

Ancestry.com has also shown a willingness to “do things right” in its quest for data. For example, when nearly half a century of Pennsylvania’s death certificates became available for scanning in one fell swoop, Ancestry.com agreed to scan the original certificates for the best digital appearance rather than taking the easy way out and scanning from the state health department’s microfilms of questionable quality.

A trend just beginning to crest at Ancestry.com is expanding user-provided material, something that has been more of a hallmark of its competitor MyHeritage <www.myheritage.com>. With the new LifeStory and Media Gallery function on its family trees, Ancestry.com is encouraging its members and subscribers to post trees, photos, mementos, and family records, possibly to create a larger and more engaged subscriber base.

Changing the emphasis of family trees in an attempt to get more subscribers is good business, and claiming that Ancestry.com’s focus on family trees (many of which don’t have to be sourced and so are easily snapped) isn’t quite fair. Rather, the site should be applauded for providing the tools—such as better ways to integrate sources into the pages of the people on the public trees—and really can’t be criticized when people don’t use those tools.

The bottom line is that anyone with a continuing interest in German genealogy will be rewarded for having an Ancestry.com subscription. It’s a place to plant your family tree amidst many of the records and sources, and to help you extend that tree beyond the Atlantic Ocean, perhaps for generations. And with AncestryDNA, the site has the potential to break down brick walls created by incomplete paper trails as well as give insights into a person’s ancient pedigree.

Some of the German records on Ancestry.com are more applicable to one or the other of the two major waves of immigrants: the “first boat” of those who came in Colonial times through the early Federal period (1600s through 1800) or those of the “second boat” who came in the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. Of course, both types of records will apply in some cases.

Here is a chart of some of the unique German resources on Ancestry.com and to which group they apply more readily:

| First Wave (1600s–1800) | Second Wave (1800–1930s) | |

|---|---|---|

| Pennsylvania German Pioneers | x | |

| Rupp’s 30,000 Names | x | |

| Germans to America | x | |

| Passenger Arrival Lists | x | |

| Hamburg Embarkation Lists | x | |

| German state censuses | x | x |

| German church records | x | x (secondary to civil registration) |

| Historical Society of Pennsylvania Church and Town records | x | x |

| Evangelical Lutheran records | x | |

| German Civil Registrations | x | |

| Naturalizations | x (colonies) | x (states and federal) |

| Meyers Gazetteer | x | x |

| US census | x | |

| Emigration databases | x (primarily) |