CHAPTER 1

Ayurveda Basics You Want to Know

One of the best things about Ayurveda is how simple it is… and one of the funniest things about simplicity is how complicated we can make it! The following introduction to Ayurveda is for those who are interested and for those who are more likely to integrate changes in their diets and lifestyles if they have some understanding of how a suggestion proves beneficial.

References to classic Ayurvedic texts are also included, to ensure we don’t forget this information about healthy living comes from an extremely reliable source: thousands of years of human trial and error.

You don’t even have to read this chapter to benefit from this book. Maybe you are holding The Everyday Ayurveda Cookbook because you know your eating habits could use some improvement. That sounds great. The seasonal chapters in part two provide enough basic information to keep you eating foods that will maintain balance throughout the year’s changing seasons, without your having to think too hard about it. An intuitive understanding of the science of Ayurveda is sure to follow. The lifestyle grows with experience, so start with the cooking.

But if you do want to read about the tools before you try them, let us begin a journey into Ayurveda.

Pronounced “EYE-yer-VAY-da,” Ayurveda can be loosely translated as “the science of life.” The classic texts, however, describe Ayur, or “life,” as being made up of four parts: the physical body, the mind, the soul, and the senses (sight, hearing, touch, smell, and taste). Contrary to the Western model, which focuses on the physical body, and sometimes on the mind these days, Ayurveda has always taken into account the health of these four aspects of life.

Ayurveda, the health system of India, employs diet, biorhythms, herbal medicine, psychology, wholesome lifestyle, surgery, and therapeutic bodywork to address the root causes of disease. The science describes the disease process from early symptoms to fatality, and it includes prevention and treatments for ailments of eight therapeutic branches: internal medicine; surgery; gynecology/obstetrics/pediatrics; two varieties of geriatrics, rejuvenation of the body and rejuvenation of the sexual energy; psychology; toxicology; and disorders of the eyes, ears, nose, and mouth.

Ayurvedic hospitals and clinics abound in India. Western medicine is often used in conjunction with the traditional medicine, especially in cases of critical ailments. While Western medicine excels at resolving acute situations, Ayurveda excels as a preventive medicine, seeking to halt the progression from imbalance to disease by addressing the underlying causes early on. Used alongside Western medicine, Ayurveda can support digestion, the immune system, and the patient’s state of mind during treatment.

Where Does It Come From?

Ayurveda may be the oldest continually practiced health system in the world. The knowledge, in its current state, is believed to be anywhere from two to five thousand years old, depending on whom you talk to. The earliest information on Ayurveda is contained in the Rig-Veda, one of four bodies of ancient scripture, orally transmitted in lyrical phrases called sutras (threads). The Vedas are believed to originate from the rishis, sages in deep states of meditation. The Vedas contain information on music, mantras, ritual worship, Ayurveda, and yoga.

Of the several classical Sanskrit texts (Sanskrit is the language of ancient India) that make up the body of Ayurvedic science, three are most important: the Charaka Samhita, the Sushruta Samhita, and the Ashtanga Hridayam (a compilation of Charaka and Sushruta). All have been translated into English, and this book will occasionally reference the Ashtanga Hridayam.

How Does It Work?

Ayurveda recognizes that the human being is a microcosm (a small part; a reflection) of the macrocosm (the big picture; the universe). The human body is made up of the same elements that make up everything else around us, and we are moved by the same energies or forces that move the oceans, the winds, the stars, and the planets.

This world operates in rhythm—for example, the cycles of the sun, moon, tides, and seasons—and so do we. The introduction of artificial light, global food transportation, and a schedule so busy that we don’t notice nature’s rhythms makes it easy to get out of sync.

If a person acts as if he or she is separate from the rhythms of the macrocosm, marching to his or her own drummer (by eating tropical fruits in winter, for example, or foods primarily from bags and boxes; staying up all night; and/or breathing recycled air), the organism will get wacky. If the movements of our world are a river we are floating in, why swim upstream? You start to feel tired, don’t digest your food well, and, over time, end up “out of order.”

What’s Food Got to Do with It?

Digestion is of paramount importance in Ayurveda. The complete digestion, absorption, and assimilation of food nutrients make up the building blocks of the body, called ahara rasa, the juice of the food. When the food is chewed and swallowed, it mixes with water, enzymes, and acids. The resulting product—food matter ready to be assimilated—is the “juice.” To assimilate nature’s bounty into the body connects the microcosm to the macrocosm. Good digestion results not only in a glowing, healthy body but in a glowing consciousness as well. If you are just beginning to understand Ayurveda, it may be easier to become aware of what you are eating and how it makes you feel than it is to realize whether you are “connected.” The feelings of connection and wholeness are fostered by a good diet and a good gut, and isn’t that what everybody wants?

What’s It Got to Do with Yoga?

Yoga and Ayurveda stem from the same philosophical roots and evolved at around the same time in history. They also share the same goal: to create a union between microcosm and macrocosm. The philosophy of yoga provides a pathway for navigating the mind/body organism toward an understanding of itself as being unified with the universe. The science of Ayurveda focuses primarily on maintaining the physical body, but the link between consciousness and health is clear. Yoga, popular these days for its physical benefits, has traditionally focused more on accessing the mental and energy bodies. Yoga movements and breathing techniques may be employed by Ayurveda to stimulate an organ or system of organs or to ease stress. The further one journeys down the limb of Ayurveda that specializes in psychology, the more one is likely to run into the philosophical system of yoga.

NOTE: This book is for beginners to the Ayurvedic lifestyle and diet, who want to home in on general foods and practices for the annual cycle. The subject of yoga and Ayurveda could fill an entire book on its own and so is not covered here.

How Does Ayurveda View the Body?

In Ayurveda, human anatomy starts with the five elements: space (also called “ether”), air, fire, water, and earth. The elements create three compounds that govern specific functions and energies in the body, namely: movement, transformation, and cohesion (holding things together). When these compounds, known as doshas, are in balance and working harmoniously, the individual will enjoy smooth moving processes (digestion, circulation, etc.), clear senses, proper elimination of wastes, and happiness (satisfaction, fulfillment).

Each of these five elemental compounds manifests as certain felt qualities in the body that one can recognize simply by paying attention to bodily sensations. For example, air and space are cold and light, fire is hot and sharp, and earth and water are heavy and moist. Too much or too little of a grouping of qualities brings on imbalance in the body. A prevalence of dry and light qualities, for instance, will result in dry skin. Ayurveda manages imbalance by introducing opposite qualities and reducing like qualities. In the case of dry skin, introducing moist, heavy foods and reducing dry and light foods will alleviate the symptom.

SIMPLE AND PROFOUND HEALING

Read on to learn about keeping your system of elements, doshas, and qualities in balance.

Pancha Mahabhutas, The Five Elements

Ayurveda views the human body, as well as all forms in our universe, as being made up of differing combinations of the five elements:

• Space

• Air

• Fire

• Water

• Earth

For example, a carrot contains space, gases, the heat of the sun, and water, and its structure—hard, orange colored, and fibrous—is made of earth. A human body, like everything in the cosmos, comprises all five elements working together. Use your own body as a frame of reference for understanding the five elements.

Space. Every body has lots of space in it—usually filled with something like food, acid, fluid, and/or waste products.

• The large intestine, and indeed the entire digestive channel from the mouth to the anus, is a long, cavernous space! Without that space there, where would we put food?

• The ear, that delicate organ that sounds bounce around inside of.

• The bones are porous, hard tissue with hollow interiors, which are filled with marrow.

• The skin, our largest organ, is exposed to the qualities of space all of the time.

Air. Anywhere there is movement, there is air. Space is passive, while air moves around. And anywhere there is space, air will move. You can feel air on your skin when a breeze blows and see it moving the clouds across the sky.

• Respiration is the movement of air in and out of the nose or mouth.

• Passing gas and belching are caused by movements of air out of the intestine and stomach, respectively. If you eat excitedly, excess air is likely to get in your mouth, and you will be gassier. Bubbly drinks make you burp because you are ingesting air with your liquid.

• The sound of cracking joints is made by air moving out from the spaces between the bones.

Fire. On earth, anywhere there is heat, fire is there: a hot spring, a lightning bolt, a forest blaze. Fire of the sun warms the earth, as it does a human body. The core of the earth is fire, just as is the human core, the stomach and small intestine. Anywhere there is heat in the body, it comes from fire.

• The stomach and small intestine are fire centers: the acids and enzymes they produce are hot.

• The blood is characterized by fire, especially if you are “hot-blooded.”

• The metabolism and some hormones are hot. (Think puberty or pregnancy.)

• The function of the eye requires fire. Consider how your eyes can get hot, red, and dry if you spend too much time on the computer or in front of the TV.

Water. Water is all over the planet, in rivers, oceans, the cells of plants, and humans. As you probably know, some 80 percent of the body is made up of water, and you are filled with liquids.

• All of the mucous membranes, which cover the digestive tract, the eyes, and the sinuses, rely on water.

• The lymphatic fluid flowing through your body has a base of water.

• Blood in your circulatory system contains water.

• Digestive juices require water.

• Synovial fluid lubricating the joints is the water element keeping you juicy.

• Saliva is water flowing into the mouth for the first stage of digestion.

Earth. In nature, earth is anything solid—soil, rocks, trees, and the flesh of animals. This is the solid structure of the body and the easiest element, conceptually, to wrap your head around: it’s all the meaty stuff.

• Adipose tissue (aka fat) is extra earth element being stored.

• Muscle fiber is the earth element holding your skeleton in place.

• The stable part of your bones (not the space inside), which makes up the structure of your skeleton, is composed of the earth element.

It’s important to remember that the same five elements are moving around in all of us and in everything. We are all made of the same stuff, which is why Ayurveda views the human organism as a microcosm of the whole universe. When we eat a carrot and transform it by absorbing and assimilating its elements into our tissues, the body takes those elements of the carrot and incorporates them into its own structure, thus linking our bodies to the world outside.

REMEMBER: digestion is the most important aspect of health. If we are digesting soundly, we will feel connected to the greater whole. If the body has a hard time breaking down the carrot and making something out of it, we will feel separate, unsatisfied, tired, and eventually pretty crappy.

The Three Doshas: Functional Friends

Most people who have heard of Ayurveda have heard of the doshas. Dosha literally means “that which is at fault.”1 But doshas aren’t a problem until imbalance has been hanging around in the body awhile. These energies do good or ill, depending on whether they are in a relative state of balance. That’s why it is more important to understand how to maintain balance than it is to dwell on doshas as the bad guys.

There are three doshas, known as vata, pitta, and kapha. These are the compounds that naturally arise when the five elements come together in certain combinations to make up a human organism. Each performs a specific function in the body and manifests as a recognizable grouping of qualities.

VATA (VA-tah) is the energy of movement.

PITTA (PITT-ah) is the energy of transformation.

KAPHA (CUP-hah) is the energy of structure and lubrication together; cohesion (think glue).

Where there is space, air begins to move, and the compound qualities of space and air manifest as cold, light, dry, rough, mobile, erratic, and clear. Space and air have no heat, moisture, or heaviness, right? These qualities are inherent in fire, water, and earth instead.

The qualities of space and air are naturally going to act a certain way and have certain effects on the body. Think of vata as the currents of the body. The body knows the food goes in the mouth, then down and out. It is vata that ushers it along. There is nothing problematic about the qualities of space and air or their function. However, if a body has accumulated too many of these qualities, certain aspects can get out of balance. For instance, the fall season is windy, dry, and cold, so the body gets this way after a little while (unless, of course, one is taking care to keep warm, eat warming, moist foods, and drink warm water). Too many vata qualities can result in signs of imbalance, such as gas and constipation, increasingly dry skin, and anxiety.

HEALTHY VATA ENSURES THAT THE BODY HAS

• Consistent elimination

• Free breathing

• Good circulation

• Keen senses

TOO MANY VATA QUALITIES MIGHT CAUSE

• Gas and constipation

• Constricted breathing

• Cold hands and feet

• Anxiety, feeling overwhelmed

PITTA

Where there is fire, there has to be water to keep it from burning everything up. The resulting compound is firewater, a liquid, hot, sharp, penetrating, light, mobile, oily, smelly grouping of qualities. (Think acid, bile.) When food gets chewed, pitta moves in to break it down, liquidize it, metabolize it, and transform it into tissues. Yee-haw! No problem with that, unless of course your internal environment gets too hot or too sharp, which can result in signs of imbalance such as acidy burps or reflux, diarrhea, skin rashes, or inflammation.

HEALTHY PITTA CREATES

• Good appetite and metabolism

• Steady hormones

• Sharp eyesight

• Comprehension

• Good complexion (rosy skin)

TOO MANY PITTA QUALITIES MIGHT CAUSE

• Acid indigestion, reflux

• Dysmenorrhea

• Red, dry eyes; the need for glasses

• Tendency to overwork

• Acne, rosacea

KAPHA

Only when you add water to sand does it stick together so you can build a sand castle with it. The earth element requires water in this same way to get tissues to hold together. Kapha is like glue: cool, liquid, slimy, heavy, slow, dull, dense, and stable. This grouping of qualities provides density in the bones and fat, cohesion in the tissues and joints, and plenty of mucus so we don’t dry out. Great! That is, unless the body becomes too heavy and too sticky, which can result in signs of imbalance such as loss of appetite, slow digestion, sinus troubles and allergies, or weight gain.

HEALTHY KAPHA PROVIDES

• Strong bodily tissues

• Hearty immune system

• Well-lubricated joints and mucous membranes

TOO MANY KAPHA QUALITIES MIGHT CAUSE

• Weight gain

• Water retention

• Sinus or lung congestion

• Lethargy and sadness

Every body should have a hearty dose of all of these qualities and thus healthy, well-functioning bodily processes. One person is more fiery and prone to an acid stomach, another is more spacey and prone to drying out—that’s the truth of variation in nature. The body’s constitution, or particular makeup of the five elements, is like DNA and comes mostly from one’s parents. Understanding your constitution can help you understand which of the three compounds is likely to get out of balance in your body, so you can make choices in your diet and lifestyle that will keep your doshas in check.

It’s easy to focus on dosha, that which is at fault. But categorizing oneself as a specific dosha (“I’m so vata”) or identifying oneself with states of imbalance is not the aim of Ayurvedic wisdom. You may find it more helpful to understand and manage the general causes of imbalance first, and that’s what The Everyday Ayurveda Cookbook will teach you how to do. Start with this and learn more about your individual constitution as your Ayurveda practices grow.

Nature’s System of Checks and Balances: The Twenty Qualities

There is no thing in this universe which is non-medicinal, which cannot be made use of for many purpose and by many modes.

Vagbhata, Ashtanga Hridayam, Sutrasthana 9.10

Our world is made up of coexisting opposites. Like increases like, and opposites balance each other. The twenty qualities are how nature keeps a balance, and working with the qualities means you can help nature stay on course.

The qualities, or gunas, name the different attributes that are inherent in all substances. These pairs of opposing attributes identify the ways we feel and understand our world through comparison: it’s hot or it’s cool; it’s sharp or it’s smooth. Ayurveda has identified the ten pairs of opposites most useful as medicine. Moist and dry, heavy and light, cold and hot—all these pairings represent nature’s system of checks and balances, present in all things, including the human body. When a quality or group of qualities is present in excess (the problem can also be depletion, but excess is more likely), imbalance can occur.

A pile of hot, sharp wasabi paste served without any cooling, smooth rice intuitively sounds a little off, doesn’t it? Opposites balance each other. Ayurveda encourages balance by introducing qualities opposite to those promoting the imbalance, while reducing like qualities. For instance, one might enjoy a bit of spicy food to warm up in winter but avoid it in summer. All of the substances and experiences used as medicine (plants, meats, fruits, minerals, as well as activities) have an effect on the body, experienced as one or more of the twenty qualities. Spicy food makes you feel sweaty, and the effects of spicy food are heating and oily. The effects of lime are cool and light. See for yourself by drinking a Cardamom Limeade on a hot day (see page 185).

Once you start to think of your body’s sensations or imbalances in terms of the qualities you are experiencing, you will be able to use food as medicine, introducing substances that have a balancing effect.

The qualities are divided into two important categories: building and lightening. The balance between these two energies in the body is central to maintaining an even keel and smooth bodily processes. Building qualities are anabolic. They build mass and nourish the tissues, encourage moisture, and strengthen, ground, and stabilize the body, mind, and nerves. Examples are comfort foods that make the body feel warm, cozy, and safe, such as warm milk, root vegetable soups, and hot cereals. Lightening qualities are catabolic. They reduce mass, reduce the tissues, eliminate excess water and mucus, and put a spring in your step. Lightening foods feel refreshing, enlivening, and energizing. Examples of lightening foods are steamed vegetables with lemon, bitter greens, clear soups, fresh melon, and ginger tea.

THE TEN BUILDERS AND THEIR OPPOSITES

NOTE: In translating the Sanskrit to English, sometimes it takes more than one English word to describe the felt quality. This is why some of the qualities enlist more than one word in the table that follows. You will also notice that some of the qualities result as much from activities (in italics in the table) as they do from substances ingested.

Certain qualities will be easy to notice, while others may seem elusive. One’s awareness gets deeper with time, so just start by paying attention to the obvious and you will gradually get the hang of how your foods are affecting you.

Nature’s Tool Kit: Using the Qualities in Your Cooking

Cold is one of the qualities, or properties, Ayurveda has designated to be used as a tool for encouraging balance. Its opposite is hot. The good news is there are only ten qualities and their ten opposites, a total of twenty tools you’ll want to get to know. As you become sensitized to what these qualities feel like in your body and how they result from your food intake and activities, your intuitive choices for balance will begin to yield an autonomous sense of well-being. The twenty qualities will be referenced throughout the recipes to familiarize you with the foods that foster balance at different times of the year. Begin to think of these twenty attributes when you think about the Ayurvedic lifestyle. Take time as you eat your meals to notice how these qualities are present on your plate and in your body. Notice how you feel before and after exercise to see what qualities are manifesting: Clear or cloudy? Light or dense?

The shopping lists in the seasonal chapters will help you get organized to buy foods that balance the qualities of each season. This means the food you buy will have attributes opposite to those prevalent in the season.

BOTTOM LINE: Like increases like, so if you are feeling too hot, no matter the season, reduce foods with a heating effect and favor cooling foods from the summer chapter. If you often feel cold, introduce warming foods from the winter chapter and limit your intake of cold foods and drinks. Support your dietary choices by introducing activities that warm the body, like brisk walking. If you are accustomed to enjoying cold drinks, turn to the “Drinkables” sections in the fall and winter chapters to find some new recipe ideas (including warm smoothies—a delicious novelty).

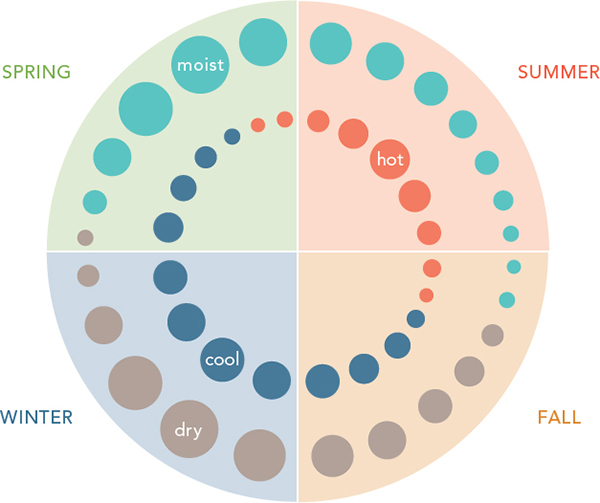

THE SEASONS AND THEIR QUALITIES |

||

Remember, the foods you will focus on in each season will have attributes opposite to those listed here, to foster balance. |

||

SPRING: Heavy, oily/damp, slow, cloudy, stable |

OPPOSITES: Light, dry, sharp, clear, mobile |

|

SUMMER: Hot, sharp/bright, oily/humid |

OPPOSITES: Cooling, slow/soft, dry |

|

FALL: Cool, light, dry, rough, mobile/windy, clear |

OPPOSITES: Warming, heavy, moist/oily, smooth, stable, cloudy/dense |

|

WINTER: Cool, very dry, light, rough, hard, clear, mobile |

OPPOSITES: Warming, moist/oily, heavy, smooth, soft, cloudy/dense, stable |

|

The Six Tastes: Sensations of Our World

In the body, the twenty qualities naturally tend to gather in groups and get aggravated all together. Since sensing the qualities can be a rather subtle art, some people find the qualities are easier to recognize in a group. The groups are called “tastes,” and the six tastes are another tool to help us integrate beneficial qualities through food choices. For example, foods that predominate in the heavy, oily, cool, and sticky qualities of water and earth elements will taste sweet, like dairy products. Foods that predominate in the dry, cool, light qualities of space and air will taste bitter, like kale.

Again, to get to know the tastes, rely on your body and your senses. The tongue will recognize a grouping of qualities as a certain taste, and a meal that contains all of the tastes is known to balance not only the palate but also the elements in the body. You might find you recognize taste more easily than individual qualities, especially at first, so learn about them here, and we will continue to grow familiar with the six tastes throughout the recipes.

Each taste results from the qualities of two elements combined.

MADHURA, SWEET TASTE, results from the qualities of earth and water (heavy, oily, sticky, cool). This taste creates a feeling of pleasure and comfort and signals food that builds strong bodily tissues (thanks to the structure of earth and the lubrication of water). By “sweet” I don’t mean sugar here; think more of the natural sweetness inherent in grains (such as rice), in fruits, in root vegetables (potatoes, carrots, parsnips, beets), and in dairy products. Sugarcane and coconut sugar are also used in Ayurveda and in this book. White sugar is considered a poison to the body and thus something to be avoided.

Foods with sweet taste are especially good for the bones, skin, hair, and reproductive tissues, but in excess they can cause problems of fat tissue and diabetes.

AMLA, SOUR TASTE, results from the qualities of fire and earth (hot, light, moist). We can guess its effect will be heating, right? Sour taste makes the mouth water (water element), causes the teeth to tingle, and makes the eyes scrunch. You will recognize sour taste by the saliva coming into your mouth. Some sour foods are lemons, tart berries, most unripe fruits (including tomatoes), store-bought yogurt, pickles, tamarind, fermented foods, and vitamin C.

Sour taste stimulates the agni, digestive fire, which makes it a great taste in a condiment or appetizer. The light quality in sour taste cleanses and energizes the body’s tissues and senses. In excess, the heat and wet of sour taste can cause irritation and swelling.

LAVANA, SALTY TASTE, results from the qualities of fire and water (hot, heavy, sharp, a little oily). Salt improves your power of taste by increasing saliva and makes everything taste better. Traditionally Ayurvedic cookery favors rock salt, but it has a strong sulphur flavor; in this book I use a lot of pink salt and sea salt. Salt taste is also present in seaweed (I use nori, dulse, and kombu in numerous recipes) and in some seafoods, especially oysters.

Foods with salty taste improve digestive activity as well as lubricate and clear obstructions of the digestive and other channels. In excess, salty taste can cause swelling, dry skin, and diminished strength.

TIKTA, BITTER TASTE, results from the qualities of ether and air (dry, cool, light). Bitter taste overrides the other tastes, might make you cringe, and is generally not a favorite, but in small amounts, you might crave it. Bitter taste is present in coffee, dark leafy greens like kale and collards, fenugreek seeds, and turmeric. But please don’t take this as a green light for coffee! Leafy greens are a far less acidic way to get your bitter taste, without irritating the stomach and drying the intestines.

Bitter is the most lightening of the tastes. Foods with bitter taste reduce fat, manage blood sugar, clean the blood of toxins, improve digestion, and reduce moisture. However, in excess, bitter taste can dry you out, make you cold, and deplete the body.

KATU, PUNGENT (SPICY) TASTE, results from the qualities of fire and air (dry, light, hot, sharp). Pungent taste excites and makes the eyes, nose, and tongue water. Found mostly in spices, pungent taste appears in black and hot peppers, garlic, mustard, onion—a lot of the ingredients used to make food taste good. Foods with pungent taste help remove mucus and dry up fat; they also dilate the channels of the body and get things moving. In excess, the hot and sharp qualities of pungency can irritate the stomach, while the dry and light qualities can deplete the reproductive tissues.

KASHAYA, ASTRINGENT TASTE, results from the qualities of air and earth (dry, cool, and heavy). Astringent taste contracts the tissues. Think of things that make you pucker and suck the water out of your mouth, like cranberries, pomegranate seeds, tea, red wine, and honey. Think about skin care astringents such as witch hazel, which contracts the pores. Astringency makes it harder for your palate to taste because it contracts your taste buds.

Foods with astringent taste tone any areas that may be slack, watery, or fatty, and they clean the blood. In excess, astringency can make you stiff, constipated, and thirsty.

The name of the game is moderation, of course. This is why Ayurveda is well known for encouraging the balanced inclusion of all six tastes in the diet. Look to the seasonal chutneys and spice blends to round out your flavors and in so doing round out your qualities, too.

The Seasonal Affect: Your Annual Cycles

It’s all about the weather. The external conditions you are exposed to greatly affect whether your body is warm, cool, oily, dry, and so on. So much so that simply eating a diet that helps to balance the effects of the weather can be all it takes to allow your body to do its thing—that is, to keep healthy.

Rtucharya means “seasonal regimen.” Simply eating the recipes from the seasonal chapters will get you started on this aspect of the Ayurvedic lifestyle. Changing your foods with the weather keeps you well. You don’t have to memorize the following information or intellectually understand the changes—you need to feel for them in your annual cycles. Ayurveda’s description of the seasonal affects provides a language to describe seasonal changes and to guide us into feeling the qualities of the natural world that affect us. If it doesn’t make sense today, it’s OK! Keep noticing and feeling—that’s the Ayurvedic lifestyle.

Traditionally, Ayurveda recognized six seasons, because the weather of the Indian subcontinent sees varying levels of heat, cold, and moisture, including monsoons. For our purposes in the West, we identify four seasons, this way:

SPRING: Cool and damp

SUMMER: Hot and humid

FALL: Cooling and increasingly dry

WINTER: Cold and dry

If your seasons don’t follow the same pattern described here—a wet and cool spring, then a hot and humid summer, followed by a dry fall, leading into a cold and dry winter—please see “Adapting for Different Climates” (page 63).

Here’s how an annual cycle changes . . .

In spring, the environment is cool as it emerges from winter, but now winter’s dryness gives way to damp. As the thaw begins and rains come, the body no longer needs thick mucus to protect it, and the mucus begins to melt. Just as the sap runs in maple trees, the body produces an unctuous, slow, cloudy liquid in need of reduction. Reactions to this cool, damp time of year may look like sinus and chest congestion, loss of appetite, sluggish digestion, lethargy, and/or sadness.

The tastes that balance spring are pungent, bitter, and astringent. Pungency warms, melts, and mobilizes; bitter and astringent tastes lighten and reduce excess moisture. Reduce building foods, be sure to exercise, and eat only when hungry.

In summer, the weather increasingly warms and may be wet. Keeping the body cool becomes important as the summer gets on. Reactions to hot and humid qualities (oily, penetrating, mobile) may look like acne, inflammatory conditions, swelling, acid stomach, and/or irritability.

The tastes that balance summer are bitter, sweet, and astringent. Sweet and bitter tastes have a cooling effect, and bitterness and astringency help reduce water in the body.

In the early fall, the body contains accumulated heat from the summer and is experiencing increasing dryness with the coming winds, which aggravates the internal heat. Reactions to the combination of heat and dryness may present as itchy or burning rashes, loose stools, dandruff, acid stomach, dry eye, and/or unstable emotions.

As late fall comes on, the heat subsides, and the body feels cold and dry. The late fall is really the beginning of winter, a time to transition. The appetite gets stronger, and it is the period to begin building.

The tastes that balance early fall are bitter, astringent, and sweet. Bitter and sweet tastes reduce heat, while astringency sucks excess water from the summer out of the body and pulls it down and out. The tastes that balance late fall are salty, sweet, and sour—same as for winter. All of these tastes warm and moisturize the body, because of their composition of fire, earth, and water elements.

In the winter, dry and cold qualities accumulate. The increase of building qualities (dense, oily, warm, smooth, and so forth) protects the body from the cold, and you will experience an increase and thickening of the mucous membranes (in the sinuses, lungs, and intestines) to protect your system from the dry quality, which will only increase until the thaw in spring. A reaction to the combination of cold and dry could look like constipation, brittle or stiff feelings in the joints or bones, anxiety, and/or weight gain.

As the late winter comes on, the body maxes out on building and mucus-producing qualities, the appetite decreases, the digestion slows down, and it is time to begin introducing a bit of lighter foods—but serve them warm.

The tastes to balance winter are sweet, sour, and salty, for their building and moisturizing qualities. The addition of more pungent taste in the late winter will begin to lighten the body and sharpen the digestive fire.

In Ayurveda the effect the seasonal variations have on the body is important enough to be named as one of the three main causes of imbalance.

SEASONAL CLEANING

How Do We Get Out of Whack?

THE THREE CAUSES OF IMBALANCE

Ayurveda recognizes three main causes of disease and imbalance, called trividha karana. If the human being manages these three areas well, the body should remain in a state of relative balance, and the progression from imbalance to disease will not occur.

The three factors are:

• KALA: Time of day and time of year (seasonal affect)

• ARTHA: Too much or too little use of the sense organs

• KARMA: Actions and activities pertaining to body, speech, and mind,2 which includes prajnaparadha, crimes against wisdom

KALA: THE SEASONAL AFFECT

The organization of recipes and seasonal discernment in this book is intended to balance the seasonal affect. If you are new to Ayurveda, all you need to know is that if you follow the big lunch/small supper principle, make seasonal food choices, and observe a bit of lifestyle routine, you will lower your risk of getting sick at the change of seasons. Think about it: spring and fall, the major junctures in weather changes, are the times when many people become ill with colds, flus, and allergies. This book will get you cooking with a sense of what the seasonal diet is all about and get you tasting your way through the annual cycle. I’ll bet you feel better, sharing in nature’s routine.

The effects of seasonal variation can cause the body to go out of balance. The need to keep warm in fall after trying to keep cool all summer, for example, can knock the body for a loop. If one is paying attention and responding to the changing qualities of the season—for instance, by shifting to warm, oily foods as the weather gets cool and dry in the fall—one can avoid problems caused by excessive cool and dry qualities coming suddenly into the body, such as dry skin, constipation, or cold hands and feet. A traditionally practiced monodiet at the change of seasons, as described in the spring and fall cleanse sections (see pages 282–85), also assists the body in adjusting.

ARTHA: MISUSE OF THE SENSE ORGANS

The sense organs are the body parts responsible for the five senses: ears (hearing), eyes (sight), tongue (taste), skin (touch), and nose (smell). Misuse can mean too much stimulation of the senses as well as too little. The nervous system is taxed by digesting too much information from the sense organs. The sense organ itself may begin to suffer, such as when you have red, dry, itchy eyes after too much screen time or when your tongue builds up a tolerance to salty restaurant food and you feel the need to increase your use of salt. Bringing the senses back into balance settles the nervous system, thereby reducing stress, which is often the cause of imbalance in the first place. For example, if people who have trouble sleeping limit their TV, smartphone, or computer time at night, they are more likely to enjoy a good night’s rest.

Usually the problem lies in exposing the senses to too much stimulation. Here are a few general suggestions to reduce strain on the sense organs.

Ears. Go easy on the iPod and take a break sometimes. Silence works wonders. Notice the qualities of the music you do choose to listen to and check in with yourself: is it appropriate for the time of day and your mental state? Music that is too upbeat may give you difficulty sleeping, while music containing angry lyrics might exacerbate your irritation.

Eyes. As mentioned, limit computer, smartphone, and TV time as much as possible. Track your screen activity and notice how much time per day feels appropriate for you and at what point your eyes need a break. Rest the eyes by closing them and taking a few deep breaths from time to time. If this proves difficult, try using an eye pillow, lying down with it set gently over your eyes to block out the light for a few minutes.

Tongue: Stick to natural, unrefined foods without added flavors, white sugars, or too much salt. Acclimate your taste buds to the lighter sensations of foods in their natural form. Practice right speech; notice how much you talk from day to day and whether you tend to criticize. With a little practice, quietude becomes calming.

Skin: Oil the skin daily to quiet the nerve endings. Favor natural oils, such as sesame, coconut, and almond, over conventional moisturizers. Dress warmly when needed.

Nose: Reduce your use of products containing “fragrance.” Note that cutting down on onion and garlic in your diet will lessen your need for deodorant.

MODERATING MEDIA AND CONNECTIVITY

Karma and Prajnaparadha: Crimes against Wisdom

Karma means “action.” Not necessarily good or bad, just action. Every action produces a reaction. Choosing a certain meal to eat, for example, is an action. How that meal affects your body is the reaction. According to classical Ayurveda texts, acting to suppress natural urges, such as going to the bathroom or having a good cry, can cause imbalance. The action of suppression causes a reaction over time, resulting in imbalance. Our own actions—or inactions—can get us in a pickle!

Prajnaparadha means “crimes against wisdom”—in other words, knowing what the right thing to do is but doing the opposite anyway. Why do we choose ice cream over herbal tea? Making the choice that harms instead of helps appears to be a tendency of human nature; indeed, we seem to have been doing it for at least a few millennia, according to the Ayurveda texts. Actions such as going back for seconds on dessert when you are full or staying up late when you are tired are two of those things we do knowing full well it’s not a good idea. In the beginning, turning a more aware eye to your choices, you’re likely to watch yourself commit a few crimes. It happens! Take heart, and remember that with practice you will see that making a healthy choice actually creates a positive reaction. After experiencing a few positive reactions, the healthy choice becomes more appealing.

Note that when the body is in a state of imbalance, cravings are likely to reflect that imbalance. For instance, someone with too much heat in the body might crave foods that increase heat. The imbalance itself begins to do the talking. When the body comes back toward its state of balance, the cravings will subside. For now, simply follow the general seasonal guidelines in this book to encourage states of balance. From there, you might notice certain cravings diminish without your having to think too hard about it.

What Do Balance and Imbalance Look Like?

Luckily, Ayurveda has described early signs of imbalance to help us know when we are getting off-kilter. But keep in mind, we are not all on the same axis to begin with, and some of the points listed here may never be in balance for you all the time. Imbalance is nothing to beat yourself up about. You can think of these signs as a heads-up, to help you recognize early symptoms of imbalance that can be sorted out with diet and lifestyle awareness.

Watch out for:

• Constipation (not having a bowel movement every day)

• Gas and bloating after meals

• Excessively dry skin, burning or itching sensations

• Cold hands and feet

• Frequent burping, acid indigestion

• Hot flashes or profuse sweating

• Swelling

• Congestion

• Insomnia

In a state of relative balance, you can expect to enjoy:

• A daily bowel movement first thing in the morning, one that is well formed, floating, and about the size, shape, and texture of a ripe banana

• No bloating after meals

• Consistent, hearty appetite

• Sound sleep, so you wake feeling refreshed

• Clear complexion

• Comfortable body temperature

• Easy breathing

To further help you prevent imbalance, Ayurveda tells us that disease can arise from habitually suppressing or forcing the following natural urges:

• Eliminating feces

• Urinating

• Releasing gas

• Sneezing

• Vomiting

• Thirst

• Hunger

• Sleep

• Coughing

• Breathing

• Yawning

Agni, Prana, and Ojas: Fostering Digestion, Energy, and Immunity

These three concepts are the keys to vibrant health. Supporting the digestive fire, keeping the energy circulating smoothly, and protecting our vital essence comprise the foundational trinity of Ayurvedic practice.

AGNI (UG-NEE)

Agni is a word you might recognize. It means “fire,” one of the five elements. When it comes to digestion, agni refers to jathara agni, the fire of the stomach. The classic texts of Ayurveda open with information on agni. Keeping the digestive fire strong is the number-one priority. If one has the correct amounts of water, fire, space, and food in the stomach, one should digest food well, meaning the stomach makes a nice ahara rasa, juice of the food. As mentioned earlier, the juice of the food is the building block of healthy tissues.

When agni is burning strongly, toxicity is not allowed to lodge in the tissues; rather, it breaks down and is eliminated. In this way, good digestive fire keeps the body free of ama, undigested matter, which gunks up the works, weakens the system, and promotes imbalance. The health, stamina, and luster of your body begin right in your stomach.

The jathara agni in the stomach builds like a little campfire. You must have kindling to get it started. If you put too much wood on it, the fire is smothered. If you don’t give it enough wood, the fire can’t burn strongly enough to create light and warmth.

Smothering the fire by overeating is a common cause of low agni and is easily remedied by skipping a meal to allow the fire to build up again (except in the case of eating disorders or unsteady blood-sugar levels). Any time you feel a loss of appetite, this indicates that you have a low digestive fire, and it’s a good time to skip a meal.

Ayurvedic cookery uses spices as kindling to build agni. For example, eating a small amount of fresh ginger before a meal will make you feel hungry, because adding kindling increases your fire.

The amount of water to take at a meal is specified as about one-third of the size of the stomach (think about four to six ounces). This leaves a third of your stomach for food and a third for space and air to move it around. Some of the water might be included in your food, such as a soupy stew or a watery vegetable like a cucumber. The correct amount of water ensures your digestive system makes a nice juice of the food. Quality oil, especially ghee, is considered the best lighter fluid and helps the fire reduce the food into juice. Ayurveda recommends about one teaspoon per meal.

Throughout the digestive process, the jathara agni is followed by little fires, breaking down fats and proteins, metabolizing, absorbing, and making body tissues like fats and muscles. This metabolizing process is governed by tejas, the bright, energetic essence of fire and metabolic activity.

GETTING TO KNOW YOUR DIGESTIVE FIRE

Fired up to boost your agni? Delve into chapter 2 to get to work.

Remember this: eating when you are truly hungry and eating slowly enough to sense when you begin to feel full are all you really need to do to care for your digestive fire. These simple practices can ensure the health, luster, and stamina you are looking for.

PRANA (PRAAH-NAH)

Prana, meaning something like “vital energy” or “life energy,” has become a bit of a buzzword. Those meanings are correct—but it also means so much more. Prana is the energy of life. An organism without prana is dead. Your body without prana is only a mash-up of the five elements—there’s nothing moving.

But here’s a key fact, and what fascinates me about how the ancient science of Ayurveda is reeducating us: where the attention goes, the prana follows. The life energy is a servant of the mind. This means it is ever so important to focus on the food we are eating.

Preparing our own food, taking care with how we buy it, eating it with our full attention—all the way from the shopping to the cooking to the eating, we have opportunities to increase the life energy of our foods and thus the energy we receive by eating them. If you want to feel good, pay attention!

Culturally, mealtimes tend to have a lot of focal points other than the food. Here are a few tips to build the prana potential of your meals.

Reduce mixing eating with meeting. That’s actually a slogan of mine. When I have a request for a working lunch, I suggest a teatime instead. Or else I have a quiet, square meal earlier or later that day, which frees me up to eat more lightly and depend less on that working meal for nourishment, since the attention is meant to go to the business at hand, not to the acts of eating and digesting.

Talk about the food. If you are enjoying a social or family meal, you might find the food is being served and no one even notices. Try remarking on the glorious colors, aromas, and tastes of the dishes being shared. Your enthusiasm might encourage your companions to join you in a moment of reflection. Even if the attention moves away later, try to begin the digestive process with appreciation and attention for the food.

Take three deep breaths before eating. Filling the abdominal region with breath brings prana to that area. This will help prepare the body to receive the food.

Ojas is the subtle essence of our life energy. Unlike prana, which is a movement or vibration of energy, ojas is a substance. You might think of it as the cream of the body, the richest and most nourishing stuff.

The Charaka Samhita3 describes ojas as that “which keeps all the living beings refreshed.”4 Ayurveda suggests human beings have a limited, predetermined amount of ojas. Living too large burns ojas. You arrive on earth with a full tank. If you put the pedal to the metal, you will burn the fuel up faster. Poof goes your longevity—and, along the way, your immunity.

In my home city of Boston, I see a lot of people who get out of bed, leave the house immediately, work all day without a lunch break, eat a big dinner, then go to bed. A lifestyle that consistently doesn’t leave time for the body to be nourished at midday is one way to force the body to burn its reserves. Living in fear or stress is another. Slowing the pace a bit, respecting the limitations of the body, and in general doing less will preserve ojas.

Did she say “doing less”? It’s not the global lifestyle norm these days. Even so, this is one of the main messages of Ayurveda. Humans have come to expect to operate at a ceaseless pace of forward, march! Consider that this may not be a sustainable practice.

One can build ojas and along with it the body’s immunity. This book contains a few ojas-building recipes (see box below). Ojas builders are rich foods, with warming spices to help the body digest them, and should be taken with full attention in limited quantities at the appropriate time. In fact, certain ojas-building foods are revered for their connection to our vital essence, such as dates, almonds, milk, and ghee. These foods are always offered at ceremonies in Hindu temples.

Now that you have some background on Ayurveda, let’s get down to the real nitty-gritty: the Ayurvedic eating concept.

OJAS-BUILDING RECIPES