Lyndon Johnson celebrating the opening of the Cordova Bridge, connecting El Paso and Juárez, 1959

From a distance, the border where Texas ends and Mexico begins seems distinct. When you get there, it all becomes fuzzy. Every morning hordes of American retirees cross the bridges from Texas into Mexico to buy cheap prescriptions in Mexican drug stores. And in the other direction, waves of Mexicans enter the United States, to convert their pesos into dollars and deposit them in American banks as a hedge against devaluation of the peso. International trade has made the Lower Rio Grande Valley (LRGV) one of the fastest-growing regions in the United States.

The border between the United States and Mexico is a gray area. Texas was part of New Spain and then Mexico for one hundred fifty years. When Texas won its independence, the border was never officially agreed upon. The Nueces Strip, the area between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande River, was a neutral zone for several years until the United States established the current border by military force. Spanish-speaking Texans whose forefathers held Spanish land grants are still ranching in the Nueces Strip.

The official border may be the Rio Grande, but the Border Patrol checkpoints where American immigration officials search every car and truck for illegal immigrants are some fifty miles north. There is a similar station on the Mexican side where you have to show a visa if you want to go any farther into the interior. In between these checkpoints is a hundred-mile-wide neutral zone where Tex-Mex biculturalism is an unremarked-upon fact of life.

BALLPARK NACHOS—American processed cheese ladled over tortilla chips—is a favorite snack among Mexican teens in Matamoros

Thanks to NAFTA and imports of tender U.S. beef, Tex-Mex fajitas are gaining in popularity in Monterrey. So are frozen margaritas, baby back ribs, taco salads, and ranch dressing. Meanwhile Mexican taqueros working out of taco trucks are serving gorditas, quesadillas, tripitas, mollejas, and other once-exotic Mexican fare all over the United States. Mexico and the United States seem to be blending into each other. What was once considered Tex-Mex fusion food has now become mainstream American and Mexican fare. Where do you draw the lines?

Try to imagine watching the Super Bowl without tortilla chips and guacamole.

On a road trip a few years back, I stopped at the Applebee’s on I-30 in Texarkana. I had never been to a Texas Applebee’s and I was surprised that the appetizer menu included chips and salsa, guacamole, chile con queso, nachos, and something called a “Chicken Quesadilla Grande,” which turned out to be a tortilla stuffed with grilled chipotle chicken, melted cheese, onion, tomato, bacon, and jalapeños. I always figured that Applebee’s, based in Kansas, represented the tastes of Middle America. So when did nuevo Tex-Mex catch on in Kansas?

On a 2007 trip to Monterrey, Mexico, to give a talk on Tex-Mex food to an international culture forum, my twenty-something guide, Lydia, a Monterrey native and talented music student, confessed that Applebee’s was one of her favorite restaurants. Applebee’s? In Mexico? Yes, it turns out there are more than forty Applebee’s restaurants in Mexico, including three in Monterrey alone. And they are doing extremely well.

There was also a brand-new Taco Bell in Monterrey. When Taco Bell opened its first location in Mexico City in 1992, I felt compelled to go down there and eat a taco. I felt the same compulsion when I found out there was a Taco Bell in Monterrey in 2007. So I had Lydia give me a ride out there.

The restaurant was located in the Plaza Bella Mall near an H-E-B supermarket (a Texas grocery chain) in an affluent suburb on the city’s outskirts. The bizarre menu featured such items as a “tambache” and a “tacostada.” Thanks to the photos, I was able to puzzle it out. A flour tortilla folded around a tostada and a ground beef filling is called a Crunchwrap Supreme at Taco Bell in the United States. “Tambache” is the made-up name Taco Bell has given it in Mexico.

And since rigid fried tortillas like the ones Taco Bell uses for its taco shells are called “tostadas” in Mexico, Taco Bell changed the name of their signature item from a “taco” to a “tacostada” to avoid getting into that whole what-is-a-taco debate with the Mexicans. Which would suggest that they ought to rename the chain Tacostada Bell in Mexico. While they are at it, they need to come up with a Spanish word for “spork,” that combination spoon and fork they make you eat with. Combine cuchara and tenedor and you end up with the cutesy “cuchador.” I like the macho “tenechara” better.

I sampled a few bites of a tacostada, a tambache, and a burrito with carne asado to see if there was any difference in flavor. But my fuzzy memories of Taco Bell cuisine are based on visits to the drive-through lane at three in the morning after the bar closed. As best as I can recall, this stuff tastes just as bland and gloppy as the Taco Bell junk I ate in the middle of the night back home.

Of course, the real question is: Why would people in Monterrey, Mexico, a city with awesome taquerias, carnicerias, and street vendors, eat at Taco Bell? Looking around the restaurant, I would have to say that the answer has something to do with kids.

Three of the six tables taken were occupied by familes. I went over and sat down with Alfredo, Raquel, and their son Ronaldo, who were polishing off a burrito, some nachos, and a tacostada.

Papa Alfredo liked the nachos, which you can’t get anywhere else around there. Raquel said that the picadillo is high-quality ground beef. “The food tastes good and it isn’t as greasy as the tacos you get at a taqueria on the street,” she told me. But Raquel confessed that the real reason they eat at Taco Bell is because young Ronaldo, a very picky eater, likes it.

“A lot of Mexicans are angry about Taco Bell coming here,” Lydia told me on the drive back downtown. “They say it’s watering down our culture.” But Lydia shrugs it off. College students in Monterrey aren’t quite as concerned about the encroachment of American fast food as the self-appointed guardians of Mexico’s culinary patrimony are. Besides, like college students in the United States, she likes fast food. “We already have McDonald’s, Carl’s Jr., Burger King, KFC, Bennigan’s, Applebee’s, and Chili’s, so it’s not that big a deal,” says Lydia.

Lydia prefers Carl’s Jr.’s burgers to McDonald’s, but she is most fond of Chili’s, a chain that is already hugely successful in Monterrey. “I wouldn’t go to Chili’s on a date,” she says, “But it’s right there in the mall and it’s so convenient.” She always orders the boneless chicken-wing salad.

Fifteen years ago, after eating at the first Taco Bell in Mexico City, I wrote a story equating the arrival of Taco Bell in Mexico to the sacking of Rome. But that first Taco Bell quickly went out of business. And somehow the tradition of the taco, a food that traces its origins back to the dawn of time, remained pretty much unchanged.

I don’t think the Taco Bell in Monterrey will have much luck selling ice to the Eskimos, either. Kentucky-based Yum Brands, Inc., which now owns the chain, is trying to expand internationally because Taco Bell sales are flat in the United States. If I had to guess why, I’d say Taco Bell is having trouble competing with the immigrant-run taco trucks and taquerias that are popping up all over the U.S.A.

Let the Mexican intellectuals go ahead and mock the talking Chihuahua. I say, may the best taco (or tacostada) win.

TO THE CHAGRIN of Mexican intellectuals, Taco Bell opened a location in Monterrey

THE LATINO cartoon character Condorito on a wall painting advertising a Houston carniceria

GUACAMOLE AT Los Norteños in Matamoros

4 ripe avocados

2 tomatoes, minced

½ teaspoon salt

1 clove garlic, minced

1 jalapeño pepper, seeded and minced (or to taste)

1 tablespoon freshly squeezed lemon juice

¼ onion, minced

2 tomatoes, hard stem area removed

4 green onions

4 ripe avocados

1 cup minced red onion

1 bunch of cilantro, stems removed and leaves chopped

4 teaspoons freshly squeezed lemon juice

Salt

VARIATIONS

Melt 1 pound chopped Velveeta chunks in a slow cooker or double boiler and stir in 1 can Rotel tomatoes with green chiles.

Melt 1 pound chopped Velveeta chunks in a slow cooker or double boiler and stir in one 16-ounce jar Pace Picante Sauce.

VIVA VELVEETA

Invented in 1918 by Emil Frey, an immigrant from Switzerland, Velveeta was first marketed by the Monroe Cheese Company in Monroe, New York. Kraft Foods purchased the brand in 1927. It’s not real cheese, but Velveeta doesn’t deserve its reputation as an unhealthy food. Velveeta has never contained any trans fats. It is high in saturated fat and sodium, but so is cheddar cheese. In fact, Velveeta was originally advertised for its nutritional benefits because it’s made with cheese, skim milk, and whey, a by-product of the cheese-making process that is considered to be a health food. It’s still made with the same ingredients today. Real cheese doesn’t melt and stay melted like Velveeta does–which is why most Texans consider it essential to chile con queso.

½ cup sour cream

½ cup mayonnaise

1 cup best-quality buttermilk

½ cup minced red onion

½ teaspoon minced garlic

¼ teaspoon dried thyme leaves

¼ teaspoon ground Mexican oregano

¼ jalapeño pepper, minced

2 green onions, thinly sliced

Salt to taste

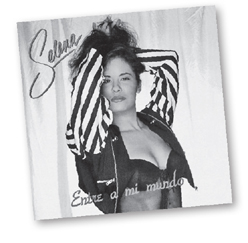

SELENA, THE QUEEN OF TEX-MEX

Selena Quintanilla-Pérez grew up in Lake Jackson outside of Houston. She began her singing career in her family’s Tex-Mex restaurant, Pappa Gallo. Selena spoke very little Spanish and had to learn the language to perform the music. She made Tejano music (as Tex-Mex music is known in northern Mexico), more popular than ever before. In 1994, shortly before her death, Selena gave a concert in Monterrey, Mexico, that electrified the audience and cemented her reputation as one of the most popular celebrities on either side of the border. There is a museum dedicated to Selena in Corpus Christi.

4 cups grated carrots

2 cups finely chopped red bell pepper

½ cup Tex-Mex Ranch Dressing

3 cloves garlic, minced

Salt and pepper

Fresh cilantro sprigs

1 cup sour cream

1 chipotle chile, minced

½ teaspoon celery salt

¼ teaspoon ground white pepper

1 tablespoon dehydrated onions

½ teaspoon curry powder

1 cup sour cream

Juice of 1 lime

¼ cup chopped fresh cilantro leaves

2 tablespoons chopped green onion

Coca-Cola is the preferred beverage at the street-food stalls of Plaza Allende in Matamoros

¼ cup lard, bacon grease, or vegetable oil

3 cups drained cooked pinto beans

½ teaspoon salt

½ cup reserved bean broth

⅛ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

VARIATION

FRIJOLES NEGROS

Substitute cooked black beans.

COOKING BEANS in a Dutch oven at the vaquero cook-off

1 pound pinto beans

2 cloves garlic, minced

½ pound cooked fajitas (or cooked ground meat)

½ cup chili powder

2 teaspoons granulated garlic

1 teaspoon granulated onion

1 tablespoon ground cumin

1 teaspoon ground Mexican oregano

2 teaspoons salt

Cayenne pepper or bottled hot sauce (optional)

2 tablespoons flour or masa harina

CHILI BEAN FRITO PIE APPETIZER

Dump a small bag of Fritos corn chips into a bowl and pour a ladleful of beans over them, then top with shredded cheese and chopped raw onion. (If you want to be authentic, ladle the chili beans directly into the bag, then add the toppings.)

ROASTED CORN, or elote, grilled in the husk at the tianguis in Monterrey

6 ears of sweet corn

Cooking spray

3 tablespoons Chile Butter

Sea salt and freshly ground black pepper

VARIATION

CORN OFF THE COB (ELOTE CON CREMA)

Remove the cooked corn from the cob with a sharp knife and mix the kernels with crema (Mexican sour cream), mayonnaise, chili powder, and parmesan cheese. Serve in a bowl as a side dish or an appetizer.

1 pound trimmed thin asparagus

2 tablespoons olive oil

1 tablespoon minced garlic

¼ teaspoon ground Mexican oregano

Salt

Freshly squeezed lime juice

2 zucchini squash

2 yellow squash

2 tablespoons olive oil

Kosher salt to taste

Freshly ground black pepper to taste