6 Rainbows in Politics and Popular Culture

Where does the rainbow end, in your soul or on the horizon? Pablo Neruda1

Between 1979 and 1987, under the sponsorship of the East German communist regime, Werner Tübke painted the largest oil painting in the history of the world: more than 120 m (400 ft) long and 14 m (45 ft) high, so large in fact that it required the construction of a special building to house it. Taking as its subject the defeat of Thomas Müntzer’s peasant army near Bad Frankenhausen in Franconia on 15 May 1525, it is titled Frühbürgerliche Revolution in Deutschland (Early Bourgeois Revolution in Germany). Its content, aside from the immense, lurid and strangely angled rainbow arching directly over the battle, is downbeat and essentially realistic. Unsurprisingly, it disappointed those who had commissioned it, hoping for an unambiguous celebration of the peasants’ protosocialistic heroism.2 The presence of the rainbow, if not its form, has an obvious basis in reality. According to an eyewitness to the battle named Hans Hut,

God almighty wanted now to cleanse the world, had taken power away from the governing authorities and given it to their subjects . . . [The peasants] all carried the rainbow as symbols in their banners. This rainbow, Müntzer told them, symbolized the covenant God had made with them. And after he had preached to the peasants continuously for three days, a rainbow did in fact appear in the sky. Müntzer drew their attention to this, encouraged the peasants and said: You see the rainbow now, it is the sign and covenant that God is on your side. This, Müntzer continued, should encourage them to fight bravely.3

Werner Tübke’s panorama Frühbürgerliche Revolution in Deutschland (Early Bourgeois Revolution in Germany), c. 1976–87.

But fight bravely they did not; and despite outnumbering the professional forces mustered against them, Müntzer’s believers armed with scythes and flails were crushed utterly, and inflicted a mere handful of casualties on the opposing side. In Thomas Nashe’s proto-novel The Unfortunate Traveller (1594), the hero Jacke Wilton becomes mixed up in the siege of the Westphalian city of Münster in 1535, which had been taken over by radical Anabaptists and transformed into a communistic and polygamous theocracy. Nashe’s text suggests that there, too, the victory of the fanatics was mis-foretold by a rainbow, but in the event, they were

|

Statue in Stolberg of Thomas Müntzer (1489–1525) waving his rainbow banner. |

empierced, knockt downe, shot thorough . . . [such] that one could hardly discerne heads from bullettes, or clottered haire from mangled flesh hung with gore . . . Heare what it is to be Anabaptists, to bee puritans, to be villaines.4

But whether Nashe’s rainbow was part of an otherwise lost oral tradition, or poetic licence, or merely confusion between Münster and Müntzer, remains unclear.

The idea that Müntzer’s peasants were the first modern revolutionaries, as improbable as it now appears, was part of a long and respectable intellectual tradition in Germany, beginning with the monumental historical work of Wilhelm Zimmermann (1807–1878), published in the mid-1840s. Zimmermann, a disciple of the German idealist philosopher Georg Hegel (1770–1831), personally rejected religion.5 Perhaps inadvertently, he created a warped portrait of Müntzer and Müntzer’s followers that was drained of religious content, seeing in their anti-authoritarianism ‘the greatest and only correct philosophical system devised by man’.6 The historian went on to participate in the March Revolution of 1848 and was elected as a deputy to the revolutionary Frankfurt National Assembly of 1848–9, caucusing with the left wing there. These views and activities made Zimmermann a hero to Friedrich Engels (1820–1895), co-founder of Marxism; and thus, with the benefit of hindsight, Müntzer and his ragged brethren would become unlikely icons of communism.

Rainbows, however, largely did not; and prior to the Tübke episode in the 1970s, their appearance in official socialist art was rare to non-existent.7 Throughout the first third of the twentieth century – a period that saw communist revolutions break out (with varying degrees of success) in Russia, Germany, Hungary, Finland, El Salvador and Mongolia – the rainbow motif largely failed to appear, though in China it did feature on the flag of the pre-communist republic established in 1912. One Western observer, ignorant of the many mythic resonances between rainbows and dragons, claimed that

in substituting this new national emblem for the old flag of the Chinese Empire which displayed a great Dragon with hungry jaws, the Chinese Republic seems . . . to have admitted that the days of the swallowing Dragon were over, and had been succeeded by a division of their land into strips, symbolizing the swallowing by five foreign Powers, England, France, Russia, Germany and Japan.8

Officially, however, the five ‘strips’ or stripes on the Chinese rainbow flag represented – in addition to all five colours of the rainbow as traditionally conceived there – the country’s different peoples:

the red one standing for those of the original eighteen provinces of China, the yellow for the Manchus, the blue (or, more properly, the ‘ching’) for the Mongolians, the white for the Thibetans, and the black for the folk of Chinese Turkestan.9

Communist North Korea saw an interesting blending of rainbow myth and politics, when official biographers of dictator Kim Jongil declared that the Supreme Leader’s birth on Baekdu Mountain in 1941 was ‘prophesied by a swallow and heralded with a double rainbow and a new star in the heavens’.10

A symbol in flux: the Americas, 1600–1960

Outside China and the British colony of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), where it had a religious precedent in the ‘rainbow body’ of the Buddha, the main use of the rainbow as a national or quasi-national symbol was in Latin America.11 It would be tempting to suggest that this was a result of Mexico and Peru having been Christianized beginning in the sixteenth century, when – German Peasants’ War aside – the idea that the biblical rainbow’s promises ‘applied to all living creatures and not to a particular people’ meant that the rainbow covenant ‘was peculiarly open to Christian adoption, Catholic and Protestant alike’.12 But according to Bernabé Cobo, writing in the 1600s, the peoples of the Andes had their own pre-conquest systems of heraldry, in which the arco celeste or rainbow was particularly prominent.13 By the end of the seventeenth century, indeed, the rainbow had become a favoured feature on the coats of arms that were drawn up by the Spanish heraldic authorities for those members of Native American aristocracies who had remained in the conquerors’ good books.

Wiphala and Inca rainbow flags in Lima.

This endorsement by Spain did little to diminish the rainbow’s power as an Andean symbol of anti-colonialism, however. As of 2006, 48 per cent of Bolivians favoured the adoption of the wiphala – a rainbow flag symbolizing indigenous resistance – as ‘a formal patriotic symbol’ of their country, and a seven-colour version duly became the ‘co-official’ flag of the country three years later.14 This, however, was just one of at least half a dozen versions of the wiphala to have been created in the preceding hundred years, including one for the Che Guevara-trained Maoist guerrilla force known as Túpac Katari. In all versions of the wiphala, the stripes run diagonally, so the horizontally striped rainbow flag of the city of Cuzco in Peru is not considered one, despite having a common origin in Inca culture.

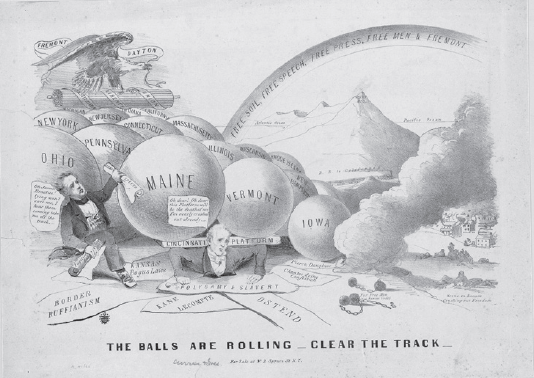

An 1856 political cartoon by Nathaniel Currier, showing Millard Fillmore and James Buchanan crushed by giant balls representing the western and northern states’ opposition to slavery and Mormonism. Republican Party slogans appear on the rainbow.

In 1938 the U.S. military promulgated a series of ‘Rainbow’ plans for the defence of the Western Hemisphere, initially only as far south as the ‘bulge’ of Brazil (‘Rainbows’ 1–3) and latterly to include the hemisphere in its entirety (‘Rainbow’ 4). The name of this series of plans was apparently intended to contrast them with single-colour and bicolour strategies of the earlier inter-war period, such as the apocalyptic ‘Red-Orange’ of 1928 which envisaged the U.S. fighting alone on four fronts against Britain, Canada, Japan and Mexico. ‘Rainbow’ 4 was never adopted because the Americans lacked sufficient military resources to execute it, not only in the interwar period but even as late as 1944. However, the nomenclature was extended into the war years with the U.S. Navy’s ‘Pot of Gold’, a plan in May 1940 to send 110,000 troops to Brazil to counter a possible pro-Axis coup there.

The reasons for the choice of this imagery for plans relating to Latin America is far from clear. However, the U.S. war planner Colonel Charles Furlong had an ‘apparently . . . comprehensive knowledge of the history, economy, geography, and culture of Latin America’ and therefore would likely have been familiar with the use of the rainbow as a symbol of national, regional and pan-Amerindian solidarity within South America.15 It might also be explained by the influence of Rainbow Countries of Central America (New York, 1926), a well-reviewed book by Wallace Thompson, a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, who chose to associate red with the soil of Costa Rica; orange with the morning sky of Nicaragua; and yellow, blue and green with the landscapes of Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador, respectively, on the basis of direct observation.

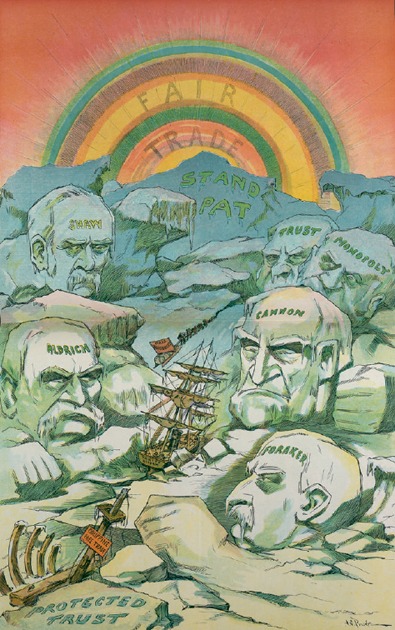

Rainbow representing fair trade, January 1907, by J. S. Pughe (1870–1909).

Col. Sherrill and Capt. Andrews turning on the Rainbow Fountain at the Lincoln Memorial, October 1924.

The reason for the naming of the U.S. Army’s 42nd ‘Rainbow’ Infantry Division, now associated exclusively with the northeast, was apparently that on its formation in 1917 it included the best regiments from more than two dozen states in every part of the country. Some sources claim that Douglas MacArthur, then the 42nd’s divisional chief of staff, suggested the name because of this unusually diverse geographical spread. MacArthur, a Protestant of a stern but non-specific sort, was Army Chief of Staff from 1930 to 1937, with wide responsibilities for war planning, and he may have been behind the raft of rainbow associations in war plans of that time. Early versions of the 42nd’s divisional badge showed the rainbow as a three-coloured half circle, while later ones were reduced to a quarter-circle, to commemorate the loss of half the unit’s personnel to death or wounds in the First World War. The U.S. Victory Medal for the same conflict, issued retroactively from April 1921, was suspended from a five-coloured, vertically striped double-rainbow ribbon, with violet along the edges and orange in the centre.

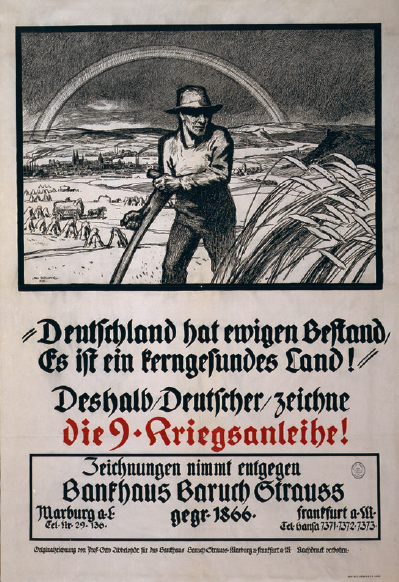

Poster for Imperial Germany’s ninth war loan, 1918, by Otto Ubbelohde (1867–1922). |

|

|

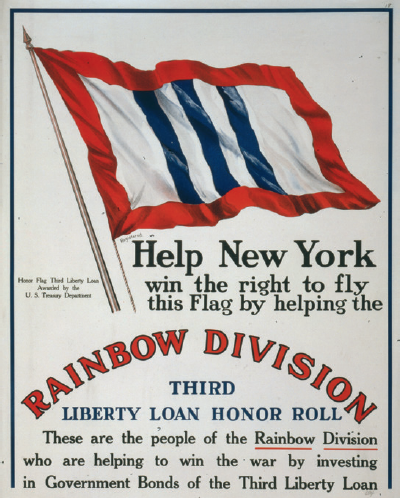

‘Honor Flag’ awarded by the U.S. Treasury Department. Lithograph by W. F. Powers Co., 1917. |

In light of this almost exclusively militarist context by the interwar years, it is somewhat surprising that the rehabilitation of the rainbow as a leftist symbol also began in America – see the discussion of Isidore Hochberg in Chapter Five, and ‘Noah’s Legacy? The Rainbow as Peace Sign’, below. In any case, as in Britain and Ireland, the American utopian political movements had been decried as ‘rainbow chasing’ since the later eighteenth century, a dismissal probably based on the scientific truth that rainbows can only be observed, and never actually approached.16 The symbolism, if any, behind Emanuel Goren’s invention of rainbow sherbet in Philadelphia in the 1950s has not been clearly identified.

Rainbows and the European left, 1600–1960

In England, ‘Rainbow’ occurs as a surname, including of one Colonel Thomas Rainbow, also Rainsborough, a martyred leader of the radical-egalitarian Levellers of the 1640s. As such, it can be exceedingly difficult to sort out whether places in the historical record called the ‘Rainbow Tavern’ or similar constituted overt political references, or scientific ones, or were mere punning based on the names of owners or frequent visitors. It has been argued that the Tory poet laureate John Dryden (1631–1700) was making a veiled reference to the 2nd Earl of Sunderland – a politically promiscuous and pseudo-pious courtier of the same era – with his reference to ‘various Iris’, a rainbow-goddess who is particularly ‘changeable’ in Dryden’s translation of Virgil, though not in Virgil’s original text.17 Given the rainbow’s history of association with Nonconformist Protestant radicalism, with which Dryden as an ex-Puritan was no doubt familiar, a rainbow image for the Whig Sunderland was especially apt.

U.S. Victory Medal, First World War.

Less than a decade later, London’s Rainbow coffee-house, located in Lancaster Court off St Martin’s Lane, became an epicentre of feverish intellectual exchange, mostly among French Protestant exiles and English atheists. Though their interests ranged from science, philosophy, theology and religious toleration to journalism, typography, theatre and chess, the net effect of the activity of the Rainbow’s customers was political, in that ‘all helped to create the climate in which the radical thought of the Enlightenment could develop later in the century’.18 The philosopher David Hume would briefly live at the Rainbow in 1739.19 Given that the dominant philosophical ethos of the ‘Rainbow Group’ was scepticism – the idea that real knowledge is unattainable – the rainbow motif is highly appropriate, even if probably accidental.

A similar phenomenon would occur beginning in 1894, when a leftist splinter group of the British Liberal Party first met in the Rainbow Tavern, Fleet Street. Two centuries earlier, this had housed the shop of Samuel Speed, printer and bookseller, who was arrested in 1666 for distributing potentially seditious works from the Cromwell era there.20 The Victorian group became known as the ‘Rainbow Circle’, a name that stuck long after they changed venue to a member’s house in Bloomsbury Square. Members of the all-male circle included future Labour prime minister John Ramsay MacDonald, future Liberal Party leader Herbert Samuel and the visionary anti-imperialist economist J. A. Hobson, who though not a socialist or communist himself became a major influence on the thought of Vladimir Lenin. For nearly four decades, the group – limited by its own rules to thirty members at any given time – served as ‘an important intellectual laboratory for . . . the welfare ideology that permeated British social-democratic politics in the early twentieth century’.21 But it split over the question of whether to support or oppose the First World War, and afterwards never recovered its pre-war stature.

A ‘patriotic’ rainbow over New York appeared in this wartime poster targeting food waste by immigrants. Lithograph by Charles Edward Chambers (1883–1941). |

|

Poster from 1917 by Frank Vincent DuMond, echoing President Woodrow Wilson’s dictum ‘Food will win the war.’

Similar usages could be found in more far-flung parts of the Empire. In 1876 E. W. Cole (1832–1918) established a book arcade which ‘at its peak . . . encompassed two blocks from Bourke to Collins Streets in Melbourne, Australia’. The rainbow sign hung at its entrance ‘stood for progressive, radical thinking’ and for books as ‘the means to creating world peace by eradicating ignorance, fear and hatred’.22

In post-Peasants’ War continental Europe as elsewhere, the rainbow retained its religious symbolism; however, it was largely shorn of any political associations until after the First World War. In the early 1920s, arguably the high water mark of communist feeling in Western Europe, it was adopted as a symbol of the non-communist Left, in the form of the International Cooperative Movement. This was first proposed in Basel in 1921 at a congress of the movement, which held (in contrast to communism) that the goals of socialism could be achieved without revolution. Professor Charles Gide – a prominent French Protestant, ‘Co-operator’ and Christian Socialist, and uncle of Nobel Prize-winning author André Gide – designed a seven-colour rainbow flag that emblematized the Co-operative concept of ‘unity in diversity’; this was formally adopted in 1925.

Noah’s legacy? The rainbow as a peace sign, 1800–2000

The British-born American radical pamphleteer Thomas Paine (1737–1809), who had been a privateer and excise officer at various times, proposed while living in Revolutionary France in the summer of 1800 that flags ‘composed of the same colors as compose the Rainbow, and arranged in the same order as they appear in that Phenomenon’ be used at sea by ships whose countries were not at war. This was the centrepiece of his ‘plan for the protection of the Commerce of Neutral Nations during War’.23 Though Paine’s proposal was not adopted, it was widely read, and can be identified as the first modern, non-religious appearance of the rainbow as a ‘peace sign’.

|

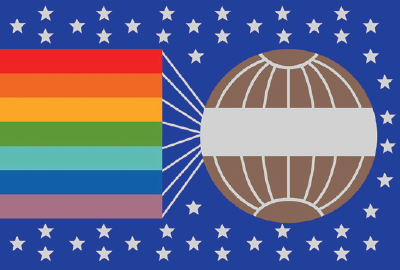

It was next used in this context in 1913, when an American Methodist minister named James van Kirk devised a busy and frankly unattractive ‘world peace flag’, consisting of a field of white stars on a dark blue ground, on which was superimposed a block of seven horizontal rainbow stripes (red uppermost) on the hoist side, tethered via eight white ropes to a predominately white globe of the Earth on the fly side. This design received considerable attention due to van Kirk’s four world tours and extensive merchandising, and the flag was officially adopted by the Universal Peace Congress, an international body that met 33 times between 1889 and the outbreak of the Second World War.

In Italy in 1961 peace activists created a flag consisting of the seven colours of the Newtonian rainbow, violet uppermost, plus an eighth, white stripe above that – presumably as a nod to earlier conventions concerning flags of truce and surrender. This white stripe was later replaced by the superimposed word pace, Italian for ‘peace’, again in white. Bridging the gap between the 1960s international peace movement and later environmentalism, Greenpeace was founded in Vancouver, Canada, in 1969 to protest against U.S. underground nuclear weapons testing in Alaska, which it was feared might cause earthquakes and tsunamis. Arising in part from Quaker anti-war principles and that religion’s practice of bearing silent witness to injustice and wrongdoing, the group’s original and most famous tactic was ship-to-ship confrontation, usually in international waters. From an exclusively anti-nuclear focus down to 1975, Greenpeace branched out via anti-whaling activities into its current, broad range of ecological pursuits. Its most famous oceangoing craft, the 40 m (130 ft) former trawler Rainbow Warrior, was sunk by French commandos in Auckland, New Zealand, in 1985, with the loss of one crewman’s life. The replacement vessel, Rainbow Warrior II, bore an eight-striped, seven-colour rainbow logo, the two outermost stripes both being white – presumably a reference to peace-movement origins, though a specific legend of the Cree Nation of American Indians is also cited as an origin for the ship’s name. One of Greenpeace’s most well-publicized and successful interventions took place in 1996, when a group of its members occupied a Shell Oil offshore drilling platform, the Brent Spar, to prevent it being disposed of by intentional sinking in the North Atlantic. Among the tactics allegedly used to dislodge Greenpeace members from the platform was constant harassment with fire hoses. In a (thankfully, bloodless) echo of the Battle of Frankenhausen nearly five centuries earlier,

Rainbow Warrior II in Turkish waters, 2009.

Suddenly the water cannons just stopped. We walked out onto the platform to see if anything was happening. On the Altair [Greenpeace support ship] we could see little silhouetted figures dancing around. We couldn’t figure out what was going on, until the Altair radioed us and told us the great news [that Shell had agreed not to sink the platform]. After that moment an incredible rainbow appeared in the sky.24

Gay Pride, kitsch and the New Left, 1969–2000

The rainbow was not in evidence during the foundational event of the modern Gay Pride movement, the riots centred on the Stonewall Inn on Christopher Street, New York City, in late June and early July 1969. It is widely believed that the six nights of rioting were somehow sparked by the death of Judy Garland on 22 June; historians have failed to find any evidence for this – there were much more immediate triggers including Mafia exploitation and police brutality – though Garland was already an icon for American gay men at the time.25 In any case, ‘Somewhere Over the Rainbow’, its socialist political meaning (if any) long since forgotten, became integral to the Gay Pride marches that began on the first anniversary of the Stonewall riots and continue to this day.

‘Somewhere over the Rainbow’ is interpreted as a wistful fantasy on a life where homosexuals can live openly and fully without judgment, social rancor, and rejection. Ironically, it is both the pathos in Garland’s rendition of the song and her self-destructive life (thought to be involuntary) that have made her an icon of contemporary gay life in America.26

Rainbow banners decorating the California Capitol Building in celebration of the outcome of Obergefell v. Hodges, 26 June 2015. |

|

As such, the song probably played a role in the immediate popularity of the first Gay Pride flag – a rainbow of eight colours, including hot pink, and with turquoise replacing blue – which was created in 1978 by San Francisco artist Gilbert Baker. Within two years, apparently due to the unavailability of sufficient quantities of pink and turquoise fabric, the design had been modified to the present six-colour design, with red uppermost, pink omitted and royal blue replacing both indigo and turquoise. A version of the six-colour Gay Pride rainbow, 1.5 km (1 mile) long and 9 m (30 ft) high, organized by Baker for the 25th anniversary of the Stonewall riots in June 1994, set a record for the longest flag in the history of the world up to that time. Baker himself broke this record nine years later, this time with a 2-km (1¼-mile) flag in the original eight colours. At one point in the late 1970s, demand for rainbow flags was so strong in the San Francisco gay community that it completely outstripped supply; in place of ‘official’ pride items, some residents adopted flags made for the International Order of the Rainbow for Girls, a still-active masonic leadership organization for eleven- to 21-year-olds that had been inaugurated at the Scottish Rite Masonic Temple in McAlester, Oklahoma, in 1922.

|

Nevertheless, the concept of Gay Pride remained largely ignored in mainstream American society as of 1978, when the American Broadcasting Company launched Mork and Mindy: a sitcom spin-off of ratings titan Happy Days, with a young Robin Williams reprising his role as space alien Mork from Ork. Mork’s trademark costume item, when in disguise as a human, was a pair of rainbow-coloured braces, mass-market imitations of which quickly became popular among children and adults. The following year, The Muppet Movie opened with popular puppet Kermit the Frog (performed by Jim Henson) wistfully singing ‘The Rainbow Connection’, written by Paul Williams and Kenneth Ascher. A near-sequel to ‘Somewhere Over the Rainbow’, it became unexpectedly popular on the radio, remaining in the U.S. top 40 charts for nearly two months, and was nominated for an Academy Award. At least one version of the film’s poster featured a prominent naturalistic rainbow. In 1994 an act called Greg and Steve released an anti-racism song aimed at children, ‘The World Is a Rainbow’, which became popular across North America; and the hemispherical Waldo Tunnel in northern California, which has long been painted with a rainbow motif, became the subject of a campaign to rename it the Robin Williams Tunnel after that actor’s death in 2014.27

Kitsch explodes

The early 1980s saw the first comprehensive integration of children’s products with children’s television programming. The Rainbow Brite universe, devised by Hallmark Cards of Kansas City, Missouri, in 1983, combined television content with books, dolls, dollhouse furniture, other toys and games, branded school supplies, puzzles, jewellery and cosmetics, luggage, clothing, towels, radios, lamps and even bicycles. The content was driven by the struggle of the forces of colour, led by a girl named Rainbow Brite and her rainbow-tailed horse Starlite, against the forces of darkness, led by the King of Shadows and latterly, the Dark Princess and Murkwell Dismal (echoing Nathaniel Hawthorne’s ‘jollity and gloom . . . contending for an empire’).28 The same blurring of retail merchandise and content – probably traceable to the astonishing success of Star Wars action figures from the late 1970s onwards – saw Hallmark’s rival American Greetings adapt their existing Care Bears product line-up for series television and feature films, beginning in 1985.29 Each Care Bear had a ‘tummy symbol’ or ‘belly badge’ denoting its personality: a rainbow adorned the stomach of Cheer Bear, one of the original ten characters, all of whom functioned more or less as guardian angels. All Care Bears have heart-shaped noses, but Cheer Bear was unusual in that her heart-nose was red, even though her fur was pink. The My Little Pony franchise was launched in 1981 as a line of Hasbro toys (originally called My Pretty Pony), with a set of Rainbow Ponies added in 1983. The title of the My Little Pony television series of 1986 was inscribed on a rainbow in the opening sequence, and the character named Rainbow Dash has remained enduringly popular in a variety of media, including her own straight-to-DVD animated feature. There is also a My Little Pony videogame called Crystal Princess: Runaway Rainbow. The latest My Little Pony feature-length film, Equestria Girls: Rainbow Rocks, portrays the adventures of a band called the Rainbooms.30 This refers to the ability of Rainbow Dash, who is the lead guitarist for the band, to fly supersonically and create a sonic boom with a rainbow-coloured shockwave. Through the 1980s and beyond, U.S. viewers of these and other tv programmes would also have been bombarded with rainbow-centred advertisements, notably including the long-running campaigns for Lucky Charms breakfast cereal (featuring a leprechaun) and Skittles candy (‘Taste the rainbow’). Video game-maker Taito, more famous for Space Invaders, released a game called Rainbow Islands in 1987.

|

|

Perhaps the oddest rise-and-fall story in the rainbow-kitsch universe has been Lisa Frank, Inc., an Arizona-based retailer focused on school supplies, which reportedly netted its eponymous founder and her husband an average $10 million a year between 1995 and 2005. Criticized as ‘the world’s shittiest employer’ and a ‘rainbow gulag’, the company allegedly forbade its workers from speaking to one another and secretly taped their phone calls; the penalties for violations of its increasingly bizarre rules ‘ranged from verbal abuse to name-calling to screaming to automatic termination’. In the words of one of a legion of disgruntled former employees, this was ‘kind of ironic, given that they have rainbows and unicorns everywhere’.31

Inevitably, given the sheer quantity of rainbow kitsch that had been generated by the 1990s, parodies of it became more numerous. Memorable examples included the video for the Republic of Ireland’s fictive Eurovision Song Contest entry on the hit Channel 4 sitcom Father Ted;32 Saturday Night Live comedian Jimmy Fallon singing the twee theme song from PBS educational series Reading Rainbow in the signature style of Doors lead singer Jim Morrison; the parodic video game Robot Unicorn Attack, whose titular antagonist sports a rainbow mane and tail; a high-school musical called God and His Magical Rainbow Suspenders that was created as part of Fox’s hit animated series Family Guy; and the ‘Pleasure Town’ animated sequence used in place of a sex scene in the 2004 comedy film Anchorman. The ongoing popularity of rainbow kitsch items is so strong, however, that it is often impossible to tell whether a particular one is intended parodically or not. For instance, a clumsily executed animation of a smiling pink and grey cat that leaves a six-striped rainbow trail as it flies across the sky has been viewed more than 130 million times on YouTube.

Most intriguingly, the notorious underground-comics artist R. Crumb produced a ‘straight’ illustrated version of the entire biblical Book of Genesis in 2009; it was nominated for a total of five Harvey and Eisner awards, winning one. An extreme statement on the power of illustration alone to shift the meaning of a text in unexpected directions, its rainbow passages – to which Crumb arguably devotes disproportionate attention – have been criticized for focusing on Noah’s ‘stupidity or confusion’ and God’s particular displeasure at the sin of murder, as distinct from displeasure at mankind’s sinfulness in a more general sense.33

Rainbows in coalition

Popular connotations of generic niceness merged neatly with the early twentieth-century socialist theme of ‘unity in diversity’ in 1984, when African American Baptist preacher Jesse Jackson described his U.S. presidential campaign as the product of a multi-ethnic ‘rainbow coalition’ that included the disabled, small farmers, working mothers, the unemployed, gays and lesbians, the young and anyone else who felt they had been harmed by the policies of the Ronald Reagan administration.34 Soon formalized as the National Rainbow Coalition, the organization still exists, with headquarters in Chicago and branches in eight other cities. Though the extent to which Reverend Jackson’s appeal in fact reached beyond the black community has been questioned, the campaign itself was hailed as

a watershed event in the history of black politics . . . perhaps on a par with the August 1963 march on Washington, the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the election of the first black mayors in 1967.35

Rainbow PUSH Coalition members protest the impeachment of President Bill Clinton, December 1998.

More than any other single event, this sealed the rainbow’s status as a symbol of both cross-ethnic cooperation and of the Left in North America. By 1992 the ‘rainbow coalition’ phrase had caught on in the Republic of Ireland, where it was associated with

social urbanisation, cultural modernisation and institutional Europeanisation . . . encapsulated in a new type of nationalism (if that it even be) more affirmative and self-confident, sceptical of clerical authority, bridling at under-performance and corruption, and . . . a belief that the ‘civil war’ parties no longer measure up to the challenges facing the state – particularly, mass unemployment.36

Two years later, the term was applied semi-officially to the three-party left-wing ruling coalition led by John Bruton, which remained in power in Ireland until 1997.

Postcolonial Africa

To the disgust of many, the white-minority regime in South Africa would use the old Co-operative slogan ‘Unity in Diversity’ in 1981, for the celebration of the twentieth anniversary of the country’s separation from the British monarchy and Commonwealth.37 The retention of this saying after South Africa’s re-entry into the Commonwealth with the coming of democracy in 1994 may have played a role in the widespread rhetoric of the ‘rainbow people’ and ‘rainbow nation’, made famous by Archbishop Desmond Tutu and President Nelson Mandela, respectively, in a neat blending of the themes of multiculturalism and peace. In 1994 Tutu famously began describing South Africans as ‘rainbow people of God’, a reference both to the Bible story of Noah as well as to the multiple tribes and ethnic groups making up modern South Africa. Mandela borrowed this notion and altered it somewhat, describing the post-Apartheid country as ‘a rainbow nation, at peace with itself and with the world’.38 In that same year, the U.S. Agency for International Development convened a meeting in Harare, Zimbabwe with representatives of all Anglophone African countries, plus Britain, Jamaica and Nepal, for the purpose of assessing the ‘potential of radio in Africa as a tool for . . . development’. Among other things, this quickly resulted in a Nigerian radio drama called Rainbow City, focused on ‘issues of democracy and good governance’ and fully sponsored by the U.S. Information Service during its first three months on the air. Written in ‘a combination of local and national pidgins and conventional English all garnished with local or indigenous ingredients such as proverbs, idioms, [and] puns’, Rainbow City was hailed as a great success, being broadcast twice a week throughout the Islamic north of Nigeria and on sixteen stations elsewhere in the country, and supported by a ‘dependable’ network of listeners’ clubs; and its popularity seems to have played a small but important role in Nigeria’s relatively peaceful transition from military to civilian rule in 1999. According to one of its producers, the name of the show recognizes ‘diversity’:

Most of the action takes place in a typical large block of rundown flats [‘Endurance Villa’] . . . home to a mix of characters that deal with the everyday problems of survival and of getting along with each other.39

Anti-rainbow backlash

Use of the universal Buddhist rainbow flag that had been introduced in Ceylon in the mid-1880s was banned in South Vietnam in 1963 by the brutal Catholic-minority government of President Ngô Đình Diệm. Shootings of flag-ban protestors led directly to widely publicized self-immolation protests by Buddhist clergy that in turn destabilized the country, leading to the assassination of Diệm and a catastrophic decade-long U.S. intervention in the region.

In post-Apartheid South Africa, critiques of the Tutu/Mandela ‘rainbow people’ and ‘rainbow nation’ rhetoric began almost immediately, with many on the Left – particularly non-blacks – dismissing it as ‘candy-coated myth’ and a ‘flimsy illusion’.40 But this was at the end of the twentieth century, the high point of the diffusion, and therefore vagueness, of the rainbow as a political symbol, simultaneously indicating the co-operative, peace, gay rights, environmentalist and multiculturalist movements, alone or in any combination.41 This slightly absurd situation probably reached its nadir in the Westminster parliamentary election campaign of George Weiss, also known as Rainbow George, of the Vote for Yourself Party in 2001. Formerly known as Captain Rainbow’s Universal Party, it was part of the British ‘rainbow alliance’ of non-serious politicians that also included the Monster Raving Loony Party and the Beer, Fags and Skittles Party.42 Contesting all four seats in Belfast, which he hoped would be renamed ‘Belfeast’ as part of the reunification of the UK with the Republic of Ireland under the name ‘Emerald Rainbow Islands’, Weiss advocated the replacement of parliament with electronic referenda and renaming the pound sterling the ‘wonder’. Each Emerald Rainbow citizen would receive a fixed salary of 27,000 wonders a year, and be forbidden from accumulating more than 1 million wonders. The penny would be called a ‘gasp’.43

Julita Wójcik’s rainbow sculpture in Saviour Square, Warsaw, following an arson attack in 2013.

Since that colourful and unedifying time, however, the rainbow has been increasingly regarded as a sort of gay juggernaut. In 2000, the athletics programme of the University of Hawaii at Manoa dropped the rainbow from its logo and team names, allegedly to distance them from homosexuality. The following year, the International Cooperative Association suspended use of their original rainbow flag from 1925, citing its similarity to other well-known flags, and replaced it with a white flag charged with a quarter-circle rainbow splintering into a flock of rainbow-coloured doves. But even this dramatically shrunken rainbow proved too gay for some, and it has already been superseded by a plain purple flag bearing the word ‘coop’ in white.

In Warsaw’s Saviour Square in June 2012, there appeared a large rainbow arch consisting of a metal frame decorated with some 16,000 plastic flowers. This sculpture had been previously set up in Brussels during Poland’s presidency of the European Union, ‘without an overt political message beyond the need for inclusiveness’.44 Some Warsaw residents hailed its arrival as a ‘new symbol of the Polish capital’s increasing tolerance’; others tried to burn it down – at least four times in the first year – for, regardless of the original meaning ascribed to it by artist Julita Wójcik and by the staid government cultural department that sponsored her work, a very large number of Poles choose to see the rainbow arch as nothing other than pro-LGBT propaganda, with one telling an Anglo-Polish defender of the new monument that it was a ‘provocation’ comparable to ‘install[ing] a big penis in front of the Westminster Cathedral’.45 Such comments by the religious Right have led to a backlash by other religious conservatives, many of whom insist that the rainbow be seen – exclusively – as representative of God’s covenant with Noah.46 British embassies worldwide were banned from flying the rainbow flag during Gay Pride events by then-foreign secretary Philip Hammond in 2015, implying that they had commonly done so in the past; and The Telegraph called it ‘a fitting coincidence’ that natural rainbows appeared over Dublin and Cork while the results of Ireland’s historic gay-marriage referendum were being tallied.47

Most parties to this debate seem to have failed to notice that by its existence, their argument proves that the rainbow indeed means very different things to different people. It probably always will. But satirists Chris Harper and Paul Bradley struck a nerve with their suggestion that the (real) town of Rainbow City, Alabama, has given up the struggle and is contemplating renaming itself. ‘The Rainbow was a symbol of beauty, hope, promise, growth and prosperity,’ the town’s mayor supposedly told the pair in 2013. ‘But now it’s just gay.’48

Perhaps, perhaps. But as a compelling spectacle in culture as much as in nature, and a unique bridge between subjective experience and objective reality, the rainbow’s story is far from over.