Greenhouses

Enter a greenhouse and you’ve crossed the threshold of an extraordinary place. You’re greeted by a profusion of flowers and the rich textures of foliage. Sweet fragrances mix with the earthy smell of soil. Diffused light shines through the misty air. In the silence, you can almost hear the plants growing. Traffic rumbles by unnoticed, and the distractions of the “real” world seem miles away.

Although the experience is similar from greenhouse to greenhouse, the structures themselves are amazingly diverse. They can be large and complex or small and simple. They can be unheated or heated, built of glass or covered in plastic. You’ll find greenhouses on city rooftops and tucked into suburban gardens. No two are identical, even if they’re constructed from the same kit; the contents of a greenhouse make it unique. Some house vegetables (tomatoes and cucumbers), some shelter tropicals (scheffleras and dieffenbachias), and some are home to flats of germinating begonias. This section is focused on leading you through the many variables among greenhouses. Finding the perfect structure for you and what you want to grow means making the right decisions along the way. The sections that follow will help you do that.

Choosing a Greenhouse

Greenhouses can take many forms, from simple, three-season A-frame structures to elaborate buildings the size of a small backyard. They can be custom designed or built from a kit, freestanding or attached, framed in metal or wood, glazed with plastic or glass. Spend a little time researching online greenhouse suppliers and you’ll discover almost unlimited options. Although it’s important to choose a design that appeals to you and complements your house and yard, you’ll need to consider many other factors when making a decision. Answering the following questions will help you determine the type, style, and size of greenhouse that suits your needs.

How Will the Greenhouse Be Used?

What do you plan to grow in your greenhouse? Are you mostly interested in extending the growing season—seeding flats of bedding plants early in the spring and protecting them from frost in the fall? Or do you want to grow flowers and tropical plants year-round?

Your intentions will determine whether you need a heated greenhouse. Unheated greenhouses, which depend solely on solar heat, are used primarily to advance or extend the growing season of hardy and half-hardy plants and vegetables. Although an unheated greenhouse offers some frost protection, it is useful only during spring, summer, and fall, unless you live in a warm climate.

A heated greenhouse is far more versatile and allows you to grow a greater variety of plants. By installing equipment for heating, ventilation, shading, and watering, you can provide the perfect environment for tender plants that would never survive freezing weather.

How you plan to use the greenhouse will also determine its size, type, and location. If you only want to harden off seedlings or extend the growing season for lettuce plants and geraniums, a small, unheated structure covered with polyvinyl chloride (PVC) sheeting or even a cold frame—a glass- or plastic-topped box on the ground—might be all you need. If your intentions are more serious, consider a larger, more permanent building. A three-season greenhouse can be placed anywhere on your property and might even be dismantled in the winter, whereas year-round use calls for a location near the house, where utilities are convenient and you don’t have to trek a long way in inclement weather.

There are many different reasons to choose a given greenhouse. The owner of this yard opted for a traditional crested, aluminum-framed, glass-enclosed model. The use of clear glass instead of semiopaque plastic allows the greenhouse to be used for meals and relaxing (thus, the table) as well as growing favorite plants.

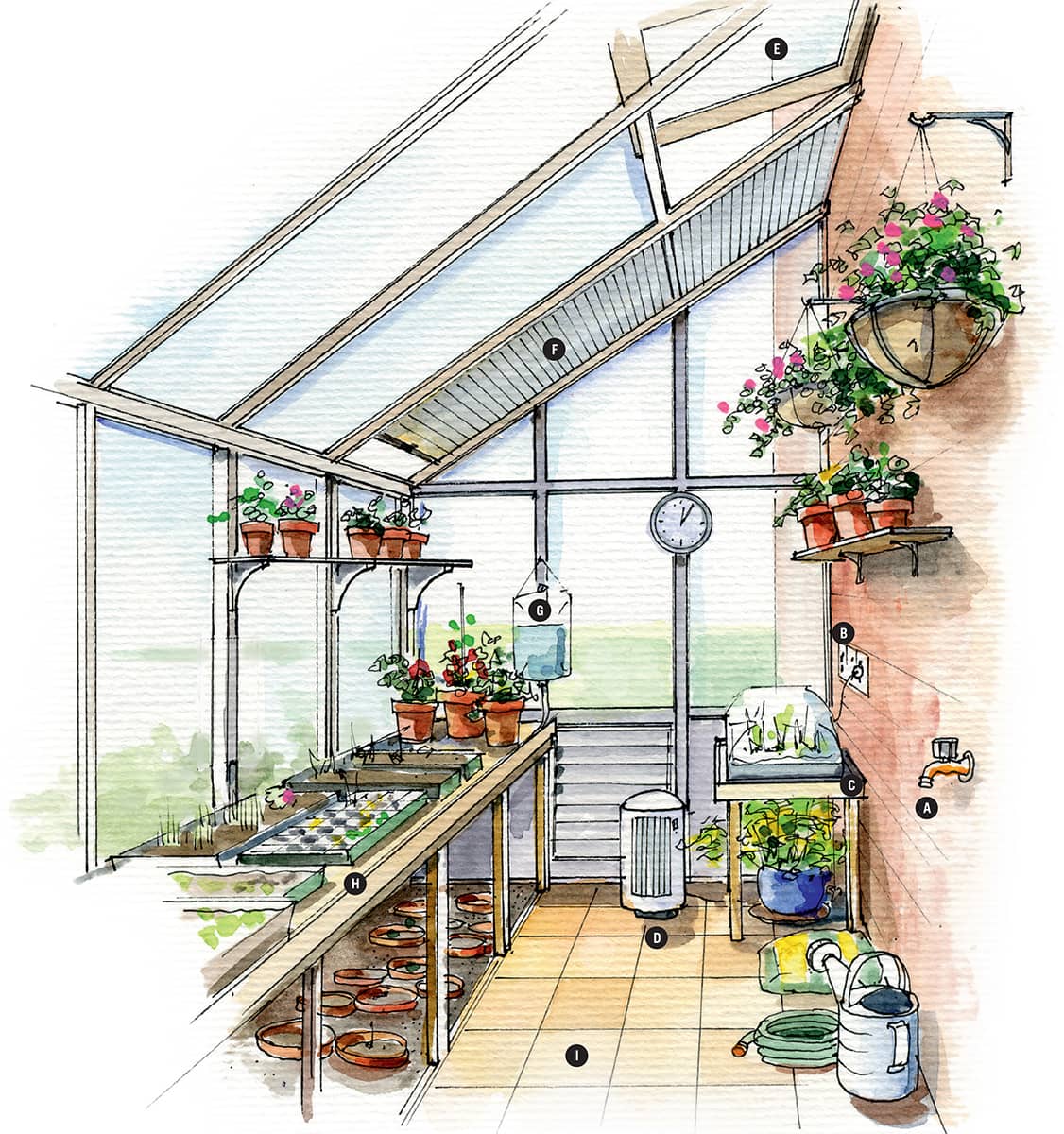

Attached to the exterior wall of the house, this lean-to-style greenhouse has all the features for complete growing success: running water (A); electrical service (B); a heated plant-propagation table (C); a heater (D) for maintaining temperatures on cold nights; ventilating windows (E) and sunshades (F) for reducing temperatures on hot days; drip irrigation system (G) for maintaining potted plants; a full-length potting bench (H) with storage space beneath; paved flooring (I) to retain solar heat.

Do I Want a Lean-to or a Freestanding Greenhouse?

Greenhouse styles are divided into two main groups: attached lean-tos and freestanding. Lean-tos are attached to the house, the garage, or an outbuilding, usually on a south-facing wall. An attached greenhouse has the advantage of gaining heat from the house. It’s also conveniently close to plumbing, heating, and electrical services, which are required to operate a heated greenhouse.

Lean-tos come in just as many variations as full-scale freestanding greenhouses do. This means you can find or build a lean-to that suits an end- or side-wall space and the style of your home. As with greenhouses, lean-tos can be simple enclosed structures meant to be used in three seasons or they can include vent fans, misters, heaters, and the other accessories that increase the usefulness of the structure.

On the downside, lean-tos can be restricted by the home’s design. They should be built from materials that complement the existing structure, and a low-slung roofline or limited exterior wall space can make them difficult to gracefully incorporate. Siting can be tricky if the only available wall faces an undesirable direction. In cold climates, they must be protected from heavy snow sliding from the house roof. Lean-tos are typically smaller than freestanding greenhouses and can be subject to overheating if they aren’t vented properly.

Standalone greenhouses can be portable or permanent. It’s wise to keep that in mind if you anticipate moving in the near future or just aren’t certain exactly where you want to fit the greenhouse into your existing landscape.

A freestanding greenhouse can be sited anywhere on the property and is not restricted by the home’s design. It can be as large or as small as the yard permits. Because all four sides are glazed, it receives maximum exposure to sunlight. However, a freestanding structure is more expensive to build and heat, and depending on its size, it may require a concrete foundation. Utilities must be brought in, and it is not as convenient to access as a lean-to. Because it is more exposed to the elements, it can require sturdier framing and glazing to withstand winds. You can also secure lighter greenhouses with an anchoring system.

How Big Should the Greenhouse Be?

In all likelihood, you’ll shop for a greenhouse that fits the “hobby” category. Larger, estate greenhouses are categorized as “conservatories,” while much smaller greenhouses, which are usually portable, are labeled “mini.”

Some experts recommend buying the largest greenhouse you can afford, but this isn’t always the best advice. You don’t want to invest in a large greenhouse only to discover that you’re not up to the work it involves.

Of course, buying a greenhouse that is too small can lead to frustration if your plant collection outgrows the space. It is also much more difficult to control the temperature. One compromise is to buy a greenhouse that’s one size larger than you originally planned, or better yet, to invest in an expandable structure. Many models are available as modules that allow additions as your enthusiasm grows.

When choosing a greenhouse, take into account the size of your property. How much space will the structure consume? Most of the expense comes from operating the greenhouse, especially during winter. The larger the structure, the more expensive it is to heat.

Be sure the greenhouse has enough room for you to work. Allow space for benches, shelves, tools, pots, watering cans, soil, hoses, sinks, and a pathway through the plants. If you want benches on both sides, choose a greenhouse that is at least 8 feet wide by 10 feet long. Give yourself enough headroom, and allow extra height if you are growing tall plants or plan to hang baskets.

How Much Can I Afford to Spend on a Greenhouse?

Your budget will influence the type of structure you choose. A simple hoop greenhouse with a plastic cover is inexpensive and easy to build. If you’re handy with tools, you can save money by buying a kit, but if the greenhouse is large, requires a concrete foundation, or is built from scratch, you may need to hire a contractor, which will add to the cost.

Location is important. If you live in a windy area, you’ll need a sturdy structure. Buying a cheaply made greenhouse will not save you money if it fails to protect your plants or blows away in a storm. And cutting costs by using inefficient glazing will backfire because you’ll wind up paying more for heating.

How Much Time am I Prepared to Invest in a Greenhouse?

You may have big dreams, but do you have the commitment to match? Maintaining a successful greenhouse requires work. It’s not hard labor, but your plants depend on you for survival. Although technology offers many time savers, such as automated watering and ventilation systems, there’s no point in owning a greenhouse if you don’t have time to spend there. Carefully assess your time and energy before you build.

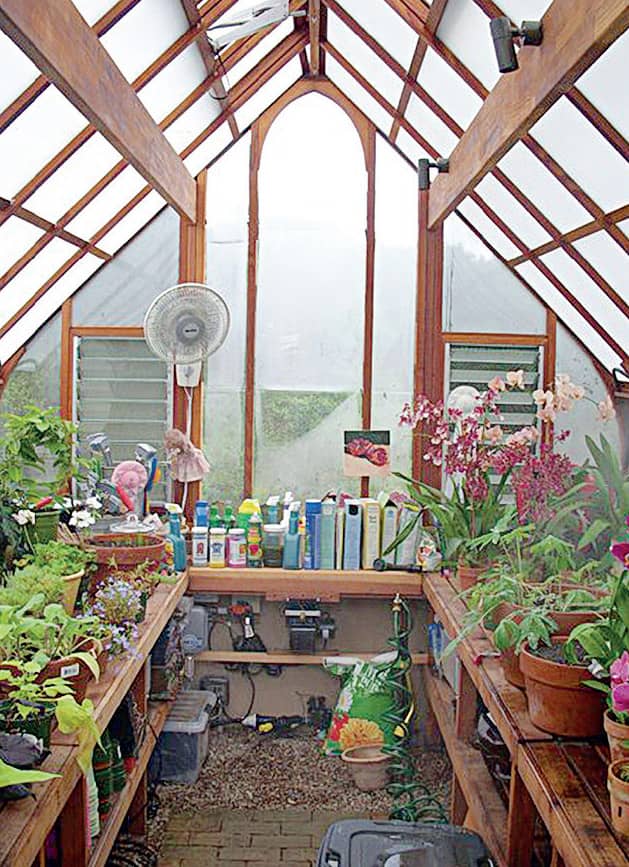

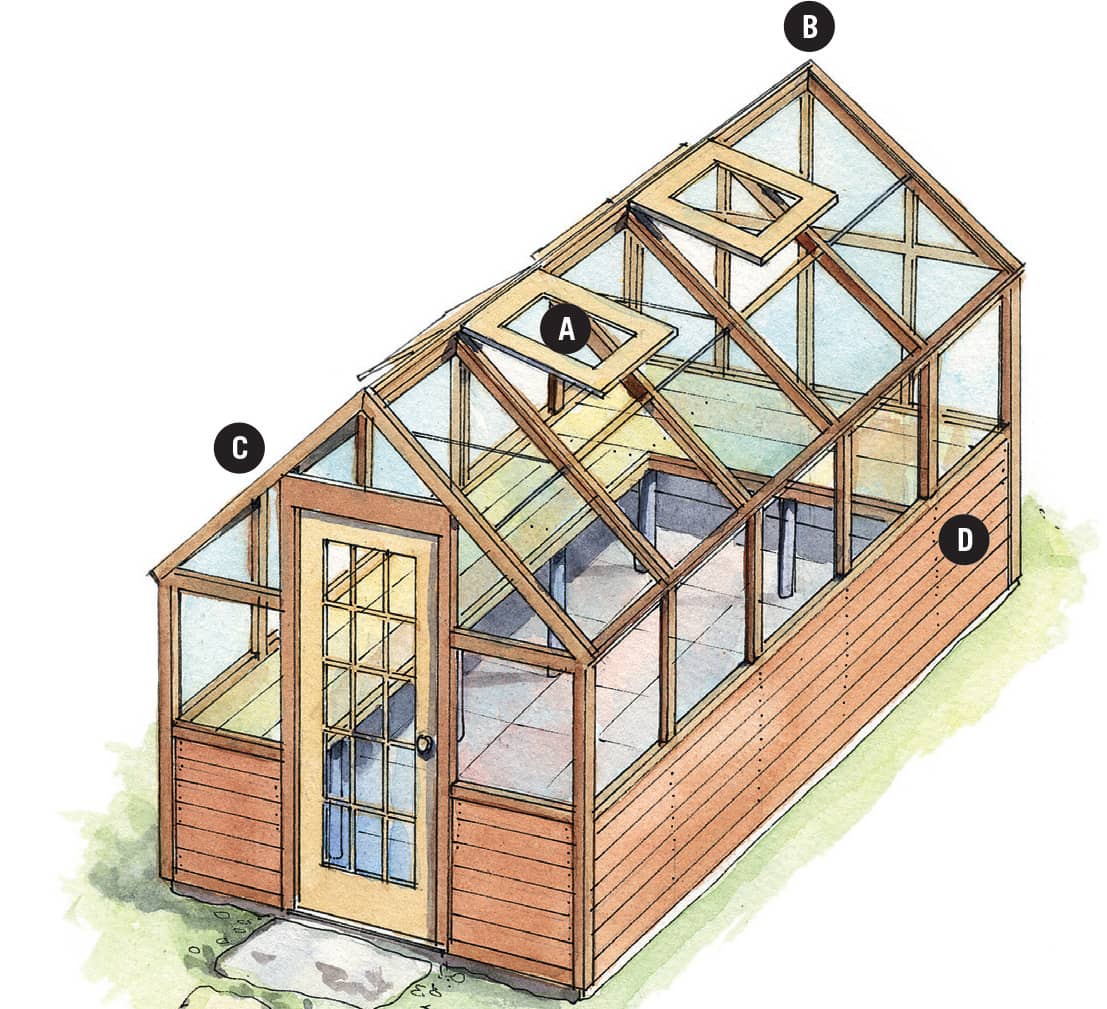

You might save money by choosing a smaller greenhouse, but if you don’t have usable room to grow everything you want to grow, you aren’t getting real value out of the structure. This beautiful redwood-framed, prefab unit may be a little pricey, but it offers abundant counter, shelf, and work-surface space as well as quality construction and glazing meant to last decades.

Where to Site Your Greenhouse

When the first orangeries were built, heat was thought to be the most important element for successfully growing plants indoors. Most orangeries had solid roofs and walls with large windows. Once designers realized that light was more important than heat for plant growth, they began to build greenhouses from glass.

All plants need at least 6 (and preferably 12) hours of light a day year-round, so when choosing a site for a greenhouse, you need to consider a number of variables. Be sure that it is clear of shadows cast by trees, hedges, fences, your house, and other buildings. Don’t forget that the shade cast by obstacles changes throughout the year. Take note of the sun’s position at various times of the year: A site that receives full sun in the spring and summer can be shaded by nearby trees when the sun is low in winter. Winter shadows are longer than those cast by the high summer sun, and during winter, sunlight is particularly important for keeping the greenhouse warm. If you are not familiar with the year-round sunlight patterns on your property, you may have to do a little geometry to figure out where shadows will fall. Your latitude will also have a bearing on the amount of sunlight available; greenhouses at northern latitudes receive fewer hours of winter sunlight than those located farther south. You may have to supplement natural light with interior lighting.

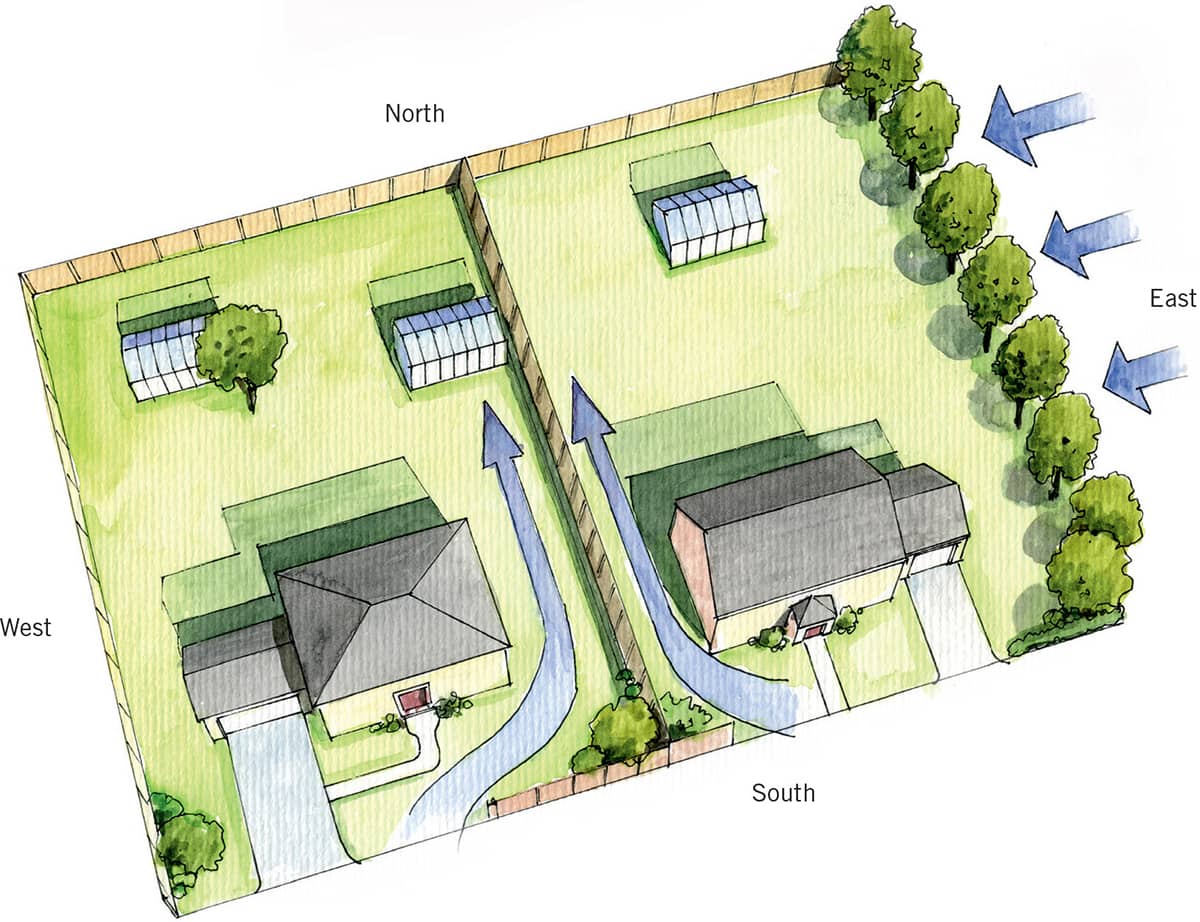

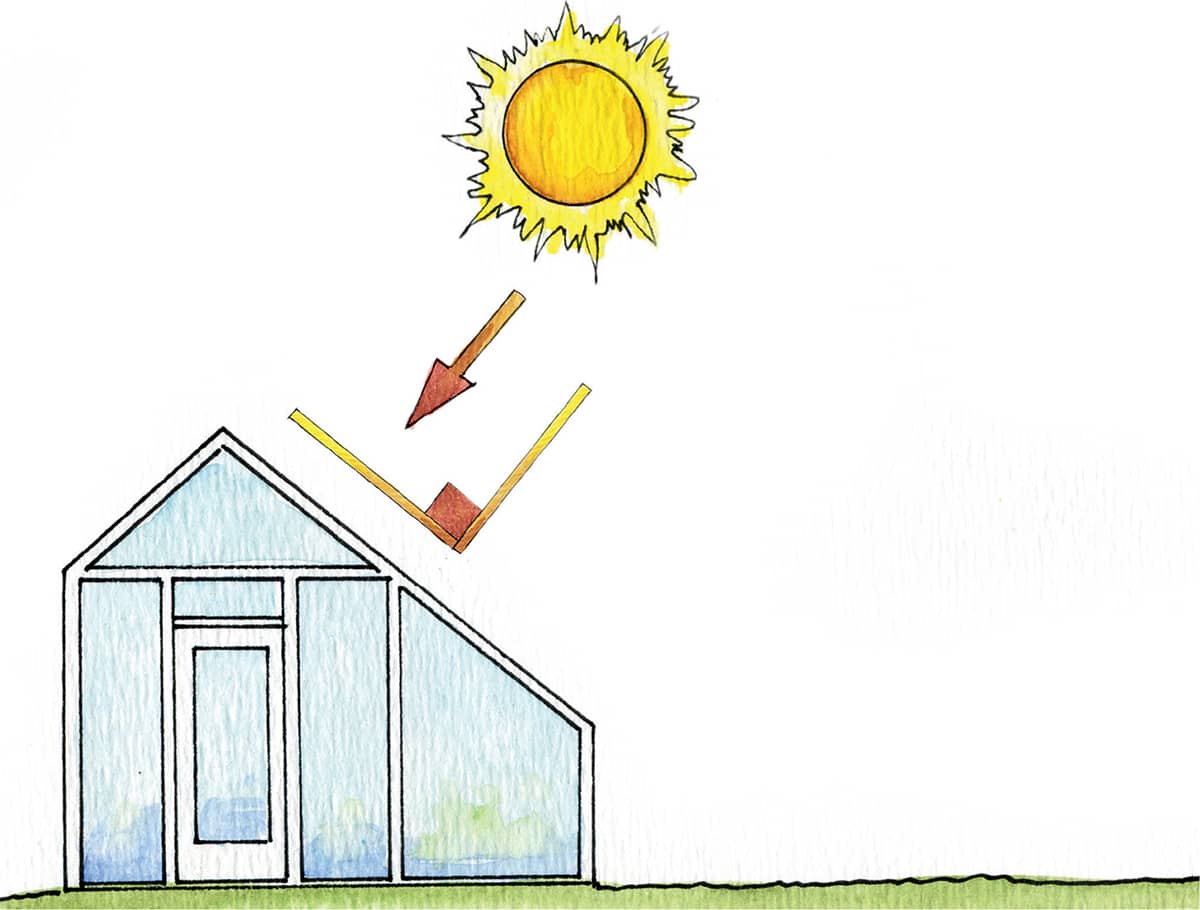

To gain the most sun exposure, the greenhouse should be oriented so that its ridge runs east to west (see illustration, below), with the long sides facing north and south. A slightly southwest or southeast exposure is also acceptable, but avoid a northern exposure if you’re planning an attached greenhouse; only shade-lovers will grow there.

The ideal greenhouse location is well away from trees but protected from prevailing winds, usually by another structure, a fence, or a wall.

Siting Factors

Several factors influence the decision of where to build your greenhouse. Some pertain to your property, some to the structure, and some to your tastes.

Climate, Shelter & Soil Stability

Your local climate and geography have an impact on the location of your greenhouse. Choose a site that is sheltered from high winds and far enough away from trees that roots and falling branches are not a threat. (Try to position the greenhouse away from areas in which children play, too.) If you live in a windy area, consider planting a hedge or building a fence to provide a windbreak, but be careful that it doesn’t cast shade on the greenhouse. Avoid low-lying areas, which are prone to trapping cold, humid air.

The site should be level and the soil stable, with good drainage. This is especially important if heavy rains are common in your climate. You might need to hire a contractor to grade your site.

Access

Try to locate your greenhouse as close to the house as possible. Connecting to utilities will be easier, and you’ll be glad when you’re carrying bags of soil and supplies from the car. Furthermore, a shorter walk will make checking on plants less of a chore when the weather turns ugly.

Aesthetics

Although you want to ensure that plants have the perfect growing environment, don’t ignore aesthetics. The greenhouse should look good in your yard. Ask yourself whether you want it to be a focal point—to draw the eye and make a statement—or to blend in with the garden. Either way, try to suit the design and the materials to your home. Keep space in mind, too, if you think you might eventually expand the greenhouse.

For maximum heat gain, orient your greenhouse so the roof or wall with the most surface area is as close to perpendicular to the sunrays as it can be.

Greenhouse Elements

At first glance, a greenhouse seems like a very simple structure: some basic framing, a good amount of glass or plastic, and voilà—a greenhouse. But actually, there is much more to this garden addition than meets the eye.

In addition to being thoughtfully situated to take advantage of the sun throughout the day and the seasons, any greenhouse must be carefully built to last while still providing an optimal environment for the plants you want to grow. That starts with choosing the right foundation and making sure the greenhouse has an appropriate floor. Not only is the base of a greenhouse important for its support, but the right floor can also serve as a heat sink, absorbing heat during the day and releasing it at night.

In addition, you’ll need to put a lot of thought into your greenhouse’s covering. Glass is traditional, but fragile and expensive. Plastic panels and sheeting are easier to work with, but you must choose the right type to create the ideal microclimate for your plants.

Any plant needs water, and depending on how large your greenhouse is, you may decide to automate the watering of your plants or to use misters to create the proper humidity. You’ll also need to figure out how to moderate the heat inside, because the temperature in a greenhouse can swing by as much as 50 degrees Fahrenheit over the course of any given day. Ventilation goes hand in glove with heat, and, of course, you’ll probably want some form of lighting so that you can check on or work with your plants after dark.

These are just some of the factors any greenhouse owner needs to consider and resolve. The purpose of this section is to help you make informed choices from among the great many options available in order to create the ideal space for whatever it is you hope to grow—not to mention yourself.

A greenhouse is composed of several major systems that perform important functions. When planning your greenhouse, you’ll need to make choices about each system, which include the foundation, floor, frame, glazing, ventilation, watering, heat, storage, and more.

Foundations

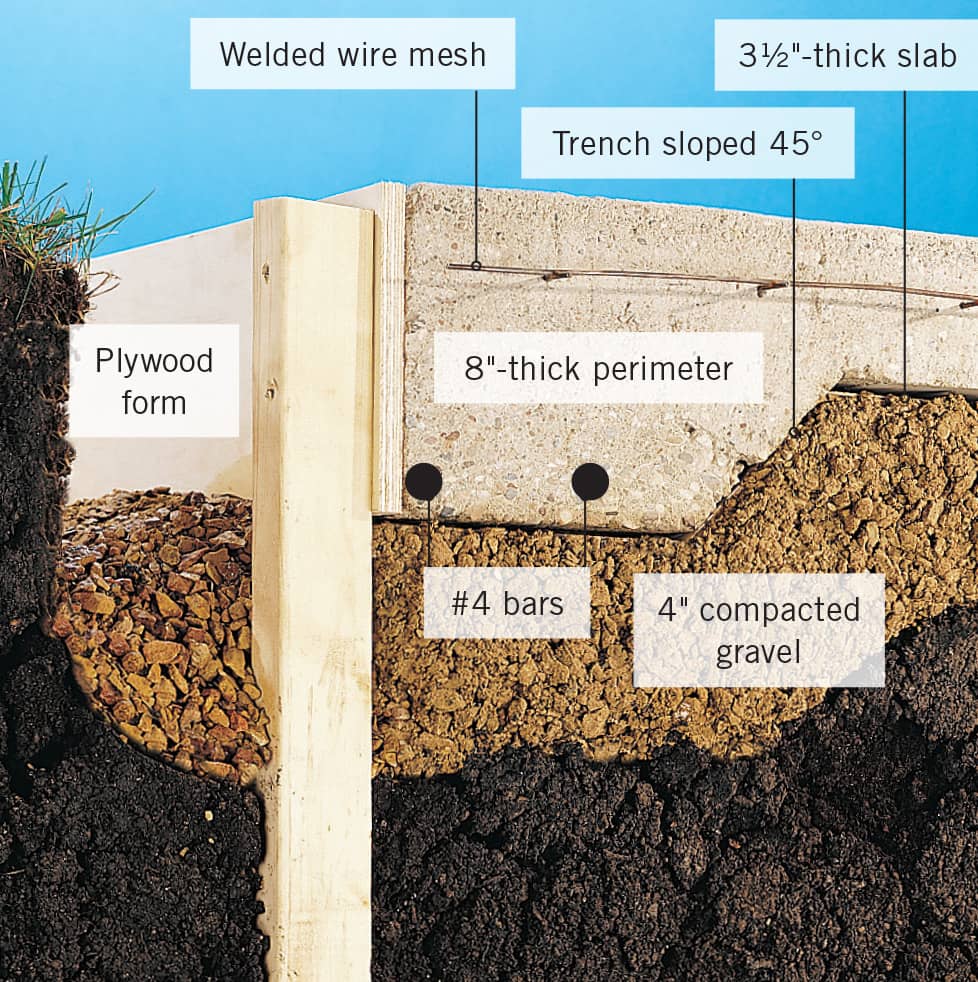

As with a house or any substantial outbuilding, a greenhouse needs an appropriate foundation. For lightweight kits and smaller greenhouses, this may be a compacted gravel base. Larger, heavier structures will most likely require a more significant foundation to prevent movement in the underlying soil from damaging the framing or glazing. A foundation should also keep any wood or metal parts off the ground to prevent premature rot or corrosion.

If you’ve purchased a kit greenhouse, the manufacturer will likely recommend appropriate foundation options. Regardless of what you’re building, you should consult your local building department to determine the codes that dictate the foundation you need to use and whether you need a permit for the foundation, the whole greenhouse, or both.

Whether you’re working from codes or simply following best building practices, the foundation needs to match the greenhouse. A kit greenhouse may come with its own metal or fabric base. For many types of prefab structures, a crushed gravel base 4 inches deep or more will serve the purpose. Other cases may call for a base of landscape timbers, concrete footings or piers, or a concrete slab. More traditional, substantial, and permanent greenhouses are often built on a kneewall of wood, brick, or stone. This is an option for most types of greenhouses, but the work and expense mean that kneewalls are rarely used with hobby greenhouses.

Earth anchors, or anchor stakes, are often used to tie down very lightweight greenhouses and crop covers to prevent them from blowing away. A typical anchor is a long metal rod with a screw-like auger end that is driven into the ground. An eye at the top end is used for securing a cable or other type of tether attached to the greenhouse.

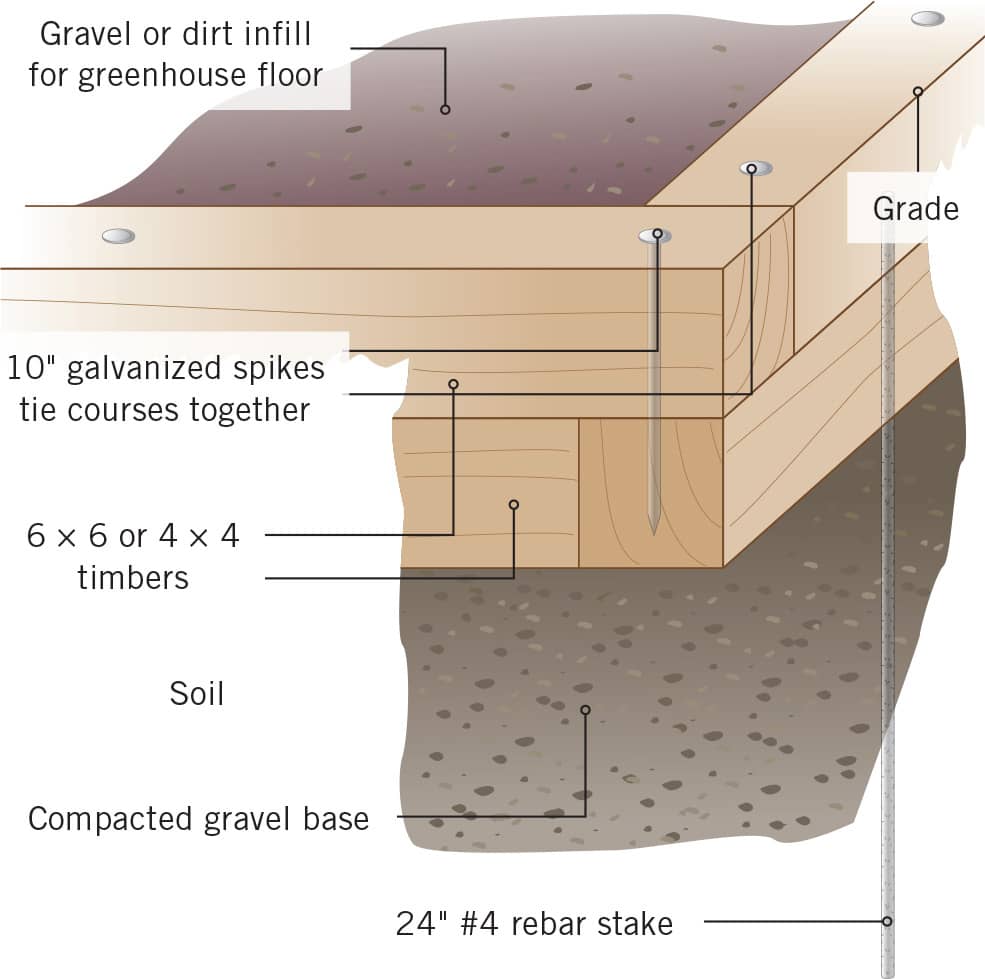

Timber foundations are simple frames made with 4 × 4, 6 × 6, or larger landscape timbers. The timber frame is laid over a leveled and compacted gravel base (which can also double as the floor or floor subbase for the greenhouse interior) and pinned to the ground with rebar stakes. One level, or course, of timbers is suitable for small greenhouses, while two courses are recommended for larger structures.

A concrete footing provides a structural base for a large greenhouse or a masonry kneewall. Standard footings are continuous and run along the perimeter of the structure. They must extend below the frost line (the depth to which the ground can freeze in winter; varies by climate) to prevent frost heave and should be at least twice as wide as the greenhouse walls they support.

Pier footings are structural concrete columns poured in tube forms set below the frost line—the same foundation used to support deck posts. Pier foundations are appropriate for some kit and custom greenhouses and are often used on large commercial hoop-style houses. Anchor bolts embedded in the wet concrete provide fastening points for the greenhouse base or wall members.

Concrete slabs make great foundations and a nice, cleanable floor surface but are overkill for most hobby greenhouses. In some areas, it may be permissible to use a “floating” footing that combines a floor slab with a deep footing edge (shown here). Otherwise, slabs must be poured inside of a perimeter frost footing, as with garage or basement construction. To prevent water from pooling inside the greenhouse, concrete slabs must slope toward a central floor drain—a job for a concrete pro, not to mention a plumber to install the drain and underground piping.

Floors

Even if your greenhouse is small or temporary, a dirt floor is often a bad idea. Watering of plants and even condensation can lead to a muddy mess that invites weeds, disease, and pests. There are plenty of inexpensive options for greenhouse floors, all of which are easy to install yourself. In general, any water-permeable surface that works for a patio or walkway will make a good floor for a greenhouse.

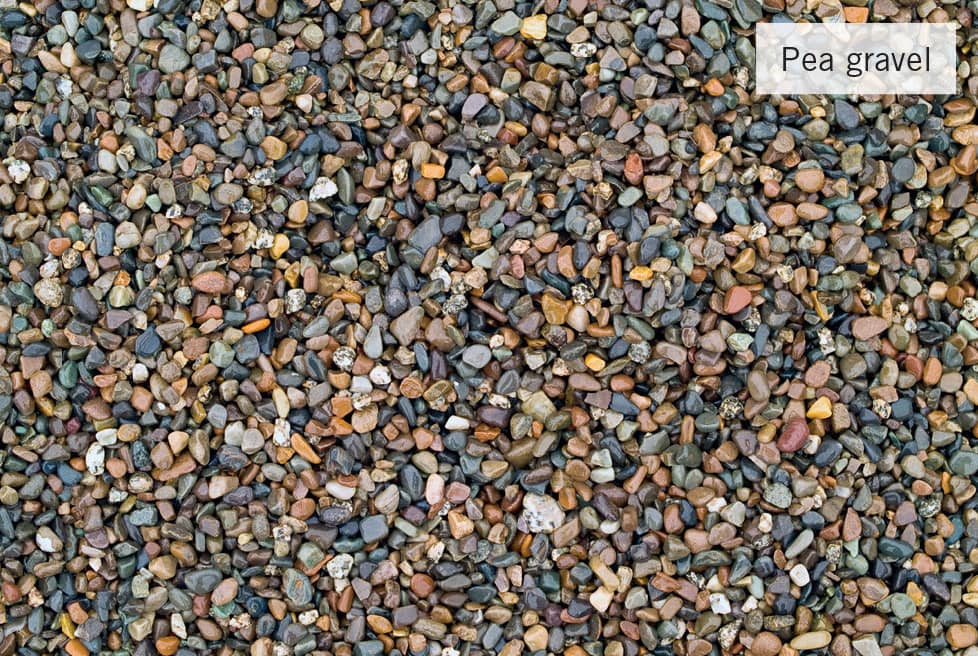

For long-term stability, improved drainage, and a level floor surface, it’s wise to support any greenhouse floor with a 4- to 6-inch subbase of compacted gravel. Cover the subbase with commercial-quality landscape fabric (not plastic; the fabric must be water-permeable) to inhibit weed growth and to separate the gravel base from the upper layers. From there, the simplest floors can be made with any type of suitable gravel, such as pea gravel or trap rock.

Brick and concrete patio pavers are other great options and offer a more finished look and feel over gravel floors. Pavers are laid over a 1- to 2-inch layer of sand and should be surrounded by a border (foundation timbers or patio edging will suffice) to keep them from drifting. Once the pavers are set, you can sweep sand over the surface to fill the cracks and lock the units in place. Another floor option—flagstone—is installed in much the same way. Keep in mind that any stone or concrete surface will also serve as a heat sink. This, alone, can be a good reason to add a stone floor to your greenhouse.

A poured concrete floor is stable and washable, and requires no routine maintenance.

Concrete pavers set in sand offer a longlasting, stable floorcovering that breathes and allows for good drainage.

Pathway gravel is the easiest and cheapest flooring to install. Pea gravel, trap rock, and some river stones are good for both drainage and cleanliness. Highly compactible materials, such as decomposed granite, remain solid and level underfoot but leave a lot of grit on your shoes (if that’s a concern). In any case, choose a material that’s comfortable to walk on; loose or large gravel or stones can be unstable.

Framing Materials

Wood and aluminum remain the most popular framing materials for hobby greenhouses, but they are far from the only options. Steel is popular for larger, more complex structures, and PVC is commonly used for more simple and portable greenhouses and hoophouses.

Every framing option has advantages and disadvantages, which is why it’s essential that you choose the best framing material for your needs both now and in the future. The key is to balance durability, weight, expense, and, of course, appearance to find just the right framing. Looking at the tradeoffs entails considering local weather conditions (do you need a high snow or wind load tolerance?), the gardening you intend on doing (do want to hang baskets in the greenhouse?), and the look that most appeals to you (do you want the greenhouse to blend in or stand out?).

Wood

Advantages: Wood is often selected for custom greenhouse framing because of the many beautiful species available. The bonus with a wood frame is that it won’t conduct heat as quickly as metal or plastic and will be less likely to shed potentially harmful condensation. It is also long lasting and durable. These qualities come at a higher cost than that of other materials, but the price tag also buys an extremely beautiful greenhouse structure. Some of the best woods for greenhouses are cedar and redwood, because both are naturally resistant to rot and insects and age well, whether finished or unfinished. Hardwoods also offer these benefits, but the cost is usually prohibitive for a hobby greenhouse. The practical choice for a utilitarian greenhouse is pressure-treated wood. In either case, wood is a wise choice if you are planning on hanging baskets or accessories from the framing, or if you intend to put up shelving.

Disadvantages: Wood framing is heavy and usually requires regular maintenance. Because it’s necessarily bulkier than other options, wood also casts more of a shadow on greenhouse plants. Rot is a potential problem, especially as the wood ages, and many types of woods will ultimately be attacked by insects—something that is never a problem with plastic or metal. You’ll also pay a higher cost for the frame than you would if you had used other materials, especially if you choose the beauty of redwood.

A pine frame with plastic glazing. This is a good option for a lightweight and inexpensive greenhouse that will be used for two or three seasons during the year.

Choose redwood for a greenhouse frame that will last years and provide an incomparable appearance to the structure.

Aluminum

Advantages: The foremost advantage of aluminum is that it is low maintenance. It is also strong and lightweight, lasts longer than wood, and can easily accommodate different glazing systems and connectors. Aluminum is used in many greenhouse kits and can be powder-coated or anodized in various colors (although the most common are white, black, and green). Aluminum greenhouse kits are typically easy to assemble and come with predrilled holes for attachments, connections, and fixtures. Some manufacturers offer “thermally broken” aluminum frames, which are made by sandwiching a thermal barrier between two layers of extruded aluminum to decrease heat loss through the frame.

This simple kit greenhouse includes a basic aluminum frame with durable polycarbonate framing.

An upscale example of a handsome prefab, aluminum-framed greenhouse. The crest and finial are finished in long-lasting baked enamel. A crest like this, as well as adding flair to the greenhouse’s look, also keeps birds from perching on the ridge—which in turn keeps the panels cleaner.

Disadvantages: Because aluminum loses heat more rapidly than wood does, this type of greenhouse is more expensive to heat. In addition, cheaper aluminum frames can be too flimsy to withstand high winds or heavy snow loads. The material can also exacerbate condensation problems inside the greenhouse.

Galvanized Steel

Advantages: Galvanized steel frames are most often used for commercial greenhouses because the material is incredibly sturdy, strong, and durable. It can stand up to severe weather and resists corrosion and fatigue.

Disadvantages: This type of framing is some of the heaviest, and framing a hobby greenhouse in galvanized steel will be extremely expensive both to ship and to build. If bumped and scratched, it can be subject to rusting in the scratches, making it better suited to a large structure for which the frame itself won’t be buffeted. The protective coating will also wear off with age.

PVC (Polyvinyl Chloride)

Advantages: PVC tubes are used in less expensive kits for hoophouses and greenhouses. The tubes make for a very low-cost frame that is durable and lightweight. The material does not rot and is entirely resistant to insects. It is also easy to clean, and although not distinctive in appearance, it looks neat and tidy. PVC frames are usually used in greenhouses meant to be portable and for beginner or intermediate gardeners.

Disadvantages: High winds, heavy snow loads, and other extreme weather can damage PVC frames. Bright sun also takes its toll, making PVC framing brittle over time. It cannot be used with glass—the frames are restricted to bendable polycarbonate panels or plastic sheeting.

A simple hoophouse frame like this is easy to assemble and doesn’t require a serious investment in money or expertise.

Greenhouse Glazing Materials

There are basically two types of greenhouse coverings: glass and plastic. The ideal glazing lets in the maximum amount of light and lets out the minimum amount of heat. But there’s more to any greenhouse covering than simply how much sunlight gets through. For instance, if you’re growing plants that are sensitive to light overexposure and burning, you may want to opt for an opaque glazing that not only lets less light through but also diffuses the light so that it doesn’t concentrate on plant surfaces.

Different materials have different lifespans. Where glass will last as long as the garden does as long as it isn’t accidentally broken, polyethylene film is likely to become brittle and fogged after a few years. A good indicator of how long any given material will last is the warranty the manufacturer offers on the panels, sheets, or rolls of the material.

Glass

Advantages: Glass is the traditional material used for greenhouse glazing, and it remains popular today for good reason. If undamaged, the material will last forever. It offers some of the best light transmission among glazing materials, doesn’t degrade under long exposure to UV radiation, and is exceedingly easy to clean. It boasts surprising tensile strength—in a frame, it can hold up to a lot of stress and wind load. Although single-pane glazing has poor insulating properties, the R-value can easily be raised by purchasing double- or even triple-pane glazing.

This stunning redwood greenhouse combines the best of both worlds—the beauty and view through clear glass windows on all walls and frosted polycarbonate panels on the roof to diffuse light.

Disadvantages: Uninsulated single-pane glass is very inefficient at retaining heat. Glass is also extremely breakable—children, tree branches, and hail are all threats to a glass greenhouse. For safety, tempered glass is recommended for greenhouses because it shatters when broken, creating small, rounded fragments, rather than sharp, jagged shards. Glass is also heavy, requiring a strong supporting framework that won’t flex under stress. Direct sunlight passing through glass is so strong it may burn some plants. Lastly, unlike some synthetic materials and products, glass panes cannot bend to accommodate curved shapes, such as a hoophouse or Gothic arch greenhouse.

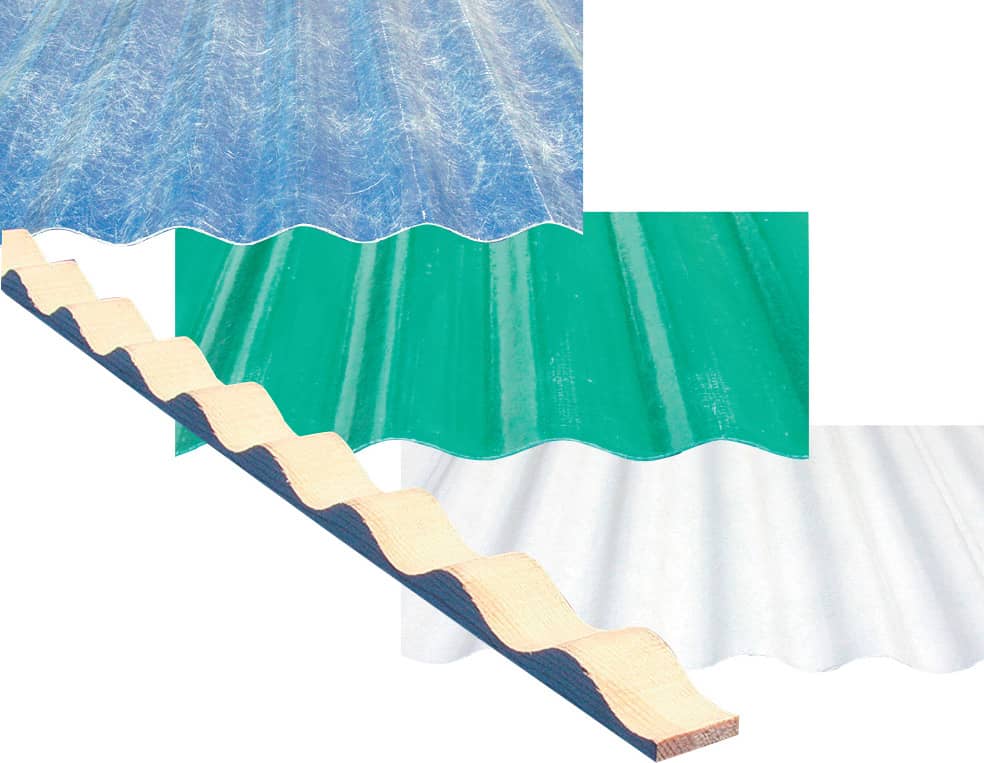

Fiberglass

Advantages: Manufacturers have vastly improved fiberglass panel formulation since the material first debuted as a potential substitute for glass panels in homes and outbuildings. Modern fiberglass panels are UV resistant and formulated to resist yellowing under prolonged sun exposure—a key problem in early panels. This material transmits almost as much light as glass does, but also diffuses that light. Fiberglass also provides much better heat retention than glass. The best panels now come with 15- or 20-year warranties.

Disadvantages: The surface of fiberglass panels is rough and captures dirt, requiring more frequent cleanings than other types of glazing. Fiberglass panels can also, under certain circumstances, experience excess condensation that can lead to plant disease and overwatering. Dirt and debris can collect in the valleys of panel ridges. Inexpensive fiberglass panels will degrade and deteriorate much more quickly than high-quality versions do.

Fiberglass panels come in clear, white, and colored varieties, such as the green shown here. The ridged panels can be challenging to install, so manufacturers supply wavy nailing strips (called “closure strips”) that make installation as easy as nailing flat panels.

Acrylic (Plexiglas)

Advantages: Acrylic panels offer excellent light transmission, similar to glass, but in a lighter material that is incredibly durable and impact resistant. The material is also UV resistant and can be molded into unusual shapes. Acrylic is less expensive than polycarbonate, and is easy drill, cut, or shape. It can also be coated to reduce condensation.

Disadvantages: Acrylic has never caught on for use in hobby greenhouses because less-expensive versions have a tendency to yellow with age, and uncoated acrylic is prone to condensation in the temperature extremes of a greenhouse.

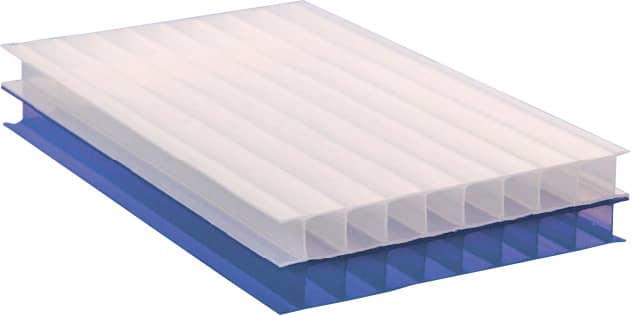

Polycarbonate

Advantages: Polycarbonate panels are light, strong, and shatter resistant. Multiwall versions retain heat far better than glass does; the panels are available in basic corrugated form, but the more prevalent types of panels are multiwalled. Manufacturers offer panels with between two and five walls—the more walls, the greater the heat retention and the lower the light transmission. The panels also come in clear and white varieties for greater light diffusion. The material is tough and durable; warranties typically run 10 to 15 years for quality polycarbonate. It is also very easy to work with and difficult to break.

Disadvantages: Although polycarbonate scratches easily, the main drawback to these panels is the high price. They are somewhat hard to clean, because certain mass-market glass cleaners can damage the material.

Polyethylene & PVC

Advantages: Greenhouse sheet coverings—primarily polyethylene plastic, but also including some PVC products—are inexpensive, easy to work with, incredibly lightweight, and adaptable to unusual shapes. They come in different thicknesses, with thicker sheet products slightly better at retaining heat without much loss in light transmission. These products usually come in white (although you can buy clear), which ensures that transmitted light is diffused and won’t burn plant leaves. The sheeting can be doubled up, which cuts down significantly on light transmission, or layers can be attached to both the outside and the inside of a structure, for improved heat retention.

Disadvantages: Polyethylene sheeting does not retain heat well and will deteriorate under prolonged sun exposure. The material is prone to rips during installation and can become brittle and yellowed in as little as two years.

Double-wall clear polycarbonate.

Triple-wall polycarbonate.

Double-wall white polycarbonate.

Water

All greenhouses need some kind of water supply system. This can be as simple as a hose connected to the nearest outdoor spigot or as complex as a frost-proof underground line extending from your basement to a special hydrant in the greenhouse. The latter is obviously more convenient, and the system can operate year-round. It’s also a pretty big job that usually requires a plumber to make the final connections. A somewhat easier alternative is to install a shallow underground water line that you drain at the end of the growing season, similar to the supply line for a sprinkler system. Or, if your water demands are not too great and your greenhouse is located near your house, maintain a rain barrel nearby.

A rain barrel can provide a ready supply of water for your greenhouse. It’s an easy water supply option, but it lacks the convenience of linking the greenhouse to your house’s water supply system.

A seasonal water supply line is similar to an all-season setup but somewhat easier to install and is just as convenient for everyday use. The supply line connects to a cold-water pipe inside the house and runs through an exterior wall above the foundation, then down into a trench (above photo). At the house-end of the trench, the initial supply run connects to the underground line (typically PE tubing) inside a valve box. The box provides easy access to a T-fitting necessary for freeze-proofing the line each fall. The supply run is buried in a 10"-deep trench (or per local code) and connects to copper tubing and a standard garden spigot inside the greenhouse.

Winterize a seasonal supply line using a shutoff valve with an air nipple. With the valve closed and the greenhouse spigot open, blow compressed air (50 psi max.) into the line to remove any water in the tubing. Then, remove the plug from the T-fitting inside the valve box (photo top right) and store it for the winter.

A greenhouse with a water supply of any sort should also have a drain. A dry well can be made with an old trash can or other container perforated with holes and filled with coarse rock. The well sits in a pit about 2' in diameter by about 3' deep and is covered with landscape fabric and soil. Dry wells are for draining graywater only—no animal waste, food scraps, or hazardous materials.

Watering & Misting Systems

If your greenhouse is fairly small and you enjoy tending plants daily—pinching off a spent bloom here, propping up a leaning stem there—you might enjoy watering by hand, either with a watering can (which is laborious, no matter how small the greenhouse) or with a wand attachment on a hose. Hand-watering helps you to pay close attention to plants and cater to their individual needs. You’ll quickly notice signs of over- or under-watering and can adjust accordingly.

However, hand-watering isn’t always practical. That's why many greenhouse gardeners use an automatic system such as overhead sprinkling and drip irrigation. This approach is convenient, especially when you’re not at home. Greenhouse suppliers sell kits as well as individual parts for automated watering systems. Be sure your system includes a timer that can be set to deliver water at specific times of the day, for a set duration, and on specific days of the week. You can also incorporate water heaters and fertilizer injectors into your system.

Overhead-sprinkler systems are attached to the main water supply and use sprinkler nozzles connected to PVC pipes installed above the benches. The system usually includes a water filter, which prevents the nozzles from clogging, and a pressure regulator. Set the system to water in the morning and during the hottest part of the day. Avoid watering late in the day so the plants will be dry before nightfall, when the temperature drops and dampness can cause disease.

Drip-irrigation systems use drip emitters to water plants a drop at a time, when moisture is needed. Each plant has an emitter attached to feeder lines that connect to a drip line of PVC tubing or pipe. Unlike overhead sprinklers, drip irrigation ensures that the plant leaves stay dry. It also helps to conserve water.

If you prefer to water plants from underneath, consider capillary mats. These feltlike mats are placed on top of the bench (which is first lined with plastic) and under the plants, with one end of the mat set into a reservoir attached to the bench. The reservoir ensures that the mat is constantly moist. Moisture from the mat is drawn up into the soil and to the plant roots when the soil is drying out. Unlike drip irrigation and overhead sprinkling, capillary-mat watering systems do not require electricity, pipes, or tubing. However, unless they are treated, the mats will need regular cleaning to prevent mildew and bacteria buildup. To ensure that the system works properly, it’s important that the bench be level.

This automatic drip-watering system is fed by a garden hose that connects to the mixing tank. In the tank, water and fertilizer are blended to a custom ratio and then distributed to plants at an adjustable rate via a network of hoses, drip pins, and Y-connectors.

NOTE: The spiral trellis supports hanging from the greenhouse roof are not part of the watering system.

Misting is a very gentle method of providing moisture to plants. Misting heads mounted on spray poles (inset) can be controlled manually or automatically. In addition to maintaining a constant state of moistness for plants, a misting system will give your greenhouse a tropical environment that many gardeners enjoy.

Regardless of the watering system you choose, use lukewarm water. Cold water can shock the roots, especially if the soil is warm. If you’re hand-watering, let the water sit in the greenhouse so it warms up to ambient temperature. (Keep it out of the sun, though—you don’t want it to get too hot). Wand watering and automatic systems can benefit from an installed water heater.

Misting

When the temperature inside the greenhouse rises and the vents open, they release humidity. Misting increases humidity, which most plants love—levels of about 50 percent to 65 percent are ideal—and dramatically decreases the temperature by as much as 20 degrees Fahrenheit. Misting systems are available through greenhouse suppliers. You can buy a complete system, which may include nozzles, tubing, PVC pipe, a humidistat, and sometimes a hard-water filter and a pressure gauge. Or you can buy the parts separately to create a customized system. The size of the greenhouse will determine the size of the system. Larger greenhouses need more nozzles and in turn more tubing and pipe.

Humidistats can automatically turn on misters and humidifiers when the humidity drops below a set level. You might also want to invest in a device to boost the water pressure. Higher pressure produces a finer mist, which cools more quickly. Suppliers recommend placing the nozzles about 2 feet apart around the perimeter of the greenhouse, between the wall and the benches. Place the nozzles underneath the benches so the mist doesn’t drench the plants. As with watering, avoid misting late in the day. Wet leaves and cold, humid air can encourage disease.

Lighting

The most basic greenhouses use only the sunlight nature provides to grow plants in a warmer environment than the plants would experience outdoors, but a greenhouse can be much more than that. If you’re willing and able to run power to the structure—or if it’s connected to your home—you can add lights that will not only extend growing days and growing seasons but will also allow you to care for your plants after dark. In fact, supplemental artificial lighting is key to turning a two- or three-season greenhouse into a four-season garden structure.

Supplementing natural light with artificial light can be tricky. Natural light is made up of a spectrum of colors that you can see (the red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet colors of the rainbow) and those you can’t see (infrared and ultraviolet). Plants absorb light from the red and blue ends of the spectrum—blue light promotes plant growth; light from the red end of the spectrum encourages flowering and budding. The red-blue light combination is easily achieved when the source is the sun but a little more difficult when you’re using artificial lighting. Intensity is also important: Lights that are set too far away or that don’t provide enough brightness (measured in lumens or foot-candles) will produce weak, spindly plants.

The three types of light bulbs used in greenhouses are incandescent bulbs, fluorescent tubes, and high-intensity discharge (HID) lights, which include metal halide (MH) or high-pressure sodium (HPS). Each has advantages and disadvantages, which is why greenhouse gardeners often use a combination of two or more types to achieve light that is as close to natural as possible.

Incandescent

Ordinary tungsten incandescent bulbs are inexpensive, readily available, and a good source of red rays, but they are deficient in blue light. They can be useful for extending daylight for some plants and for supplementing low light levels, but they are not an efficient primary source of light. Incandescent lights produce a lot of heat—hanging them too close to plants can burn foliage, but if you hang them at a safe distance, they don’t provide enough intensity for plant growth. The average life span of an incandescent bulb is about 1,000 hours.

Fluorescent

Fluorescent tubes are more expensive than incandescent bulbs, but the higher cost is amply offset by their longevity and efficiency: bulb life for fluorescents is about 10,000 hours, and they provide the same amount of light as incandescents with only one-quarter to one-third the amount of energy. They also produce much less heat than incandescent bulbs.

The right lighting in a greenhouse increases the number of hours you can work in the structure each day and expands the growing season and growing hours of plants.

Fluorescent is a better source of growth-stimulating light for your greenhouse. It must, however, be hung relatively close to plants in order to spur growth.

Fluorescent bulbs (or “lamps,” as they’re called by the lighting industry) come in a variety of colors and temperature ranges, including full-spectrum light. Cool white lamps, which produce orange, yellow-green, blue, and a little red light, are the most popular choice. To provide seedlings and plants with a nearly full spectrum of light, many growers combine one cool white lamp and one soft (or warm) white lamp in the same fixture.

Due to their energy efficiency and low heat output, fluorescent-tube fixtures are great for ambient lights that you might leave running for long periods, as well as for task lighting. They’re also the best all-around choice for starting seedlings and growing small plants. The downside to using fluorescents as grow lights is that they must be hung very close to the plant—from 2 to 8 inches, depending on the plant—to be effective. This makes them most useful for propagation and low-growing plants.

HID

High-intensity discharge (HID) lights work by sending an electrical charge through a pressurized gas tube. There are two types: high-pressure sodium (HPS), which produces light in a narrow yellow-orange-red band, and metal halide (MH), which produces a broader range of light waves but tends to be more toward the white-blue-violet end of the spectrum. Novice growers tend to use metal halide lights if they’re using grow lights at all. But more experienced greenhouse gardeners, and those who grow throughout the year, may use a combination: MH lights to start plants off and encourage early growth and bushiness, then switching to HPS as the plants mature, because HPS light encourages flowering and fruiting. In fact, although most fixtures do not allow for bulbs to be interchanged, convertible fixtures are available that do allow the gardener to switch between bulbs.

Ordinary incandescent lights aren’t particulary good sources of growth-promoting light, but they can help heat a greenhouse. And their attractive warm light also turns a greenhouse into a nighttime landscape design feature.

HID lights of both types are very expensive, but they last a long, long time. A standard 400-watt HID bulb can provide 20,000 hours of lighting. These bulbs also light a large area: that single bulb will provide enough light for 16 square feet of plants. HID lights do, however, produce a good amount of heat. Hang them high in the greenhouse, and provide plenty of ventilation in warmer months.

LED Grow Lights

As lighting technology continues to evolve, light-emitting diodes (LEDs) are growing in popularity and use. Manufacturers have developed special LED grow lights that include both blue and red light waves, effectively serving all the needs of plants—from initial growth through mature budding, flowering, and fruiting. The big bonus of these bulbs is that they last almost as long as HID lights do but cost a fraction of the price. The lights can be used with conventional fixtures and provide wide, diffuse illumination that prevents the light from ever burning plant leaves.

Heating

Novice greenhouse gardeners can gain knowledge and extend their growing season with a basic lean-to or tiny kit greenhouse. But if you’re going to take advantage of the full potential inherent in greenhouse gardening, you’ll need to heat the greenhouse. There are several ways to do that. Some techniques, such as using a heat sink, are usually meant as a complement to a main heat source. In any case, the most common and simplest way to heat your greenhouse is with a heater. The two main types are electric and fuel fired (gas, propane, kerosene, or oil).

Electric heaters are inexpensive and easy to install. They provide adequate heat for a small greenhouse in a temperate climate and are useful for three-season greenhouses. However, they are expensive to operate (although relative costs are constantly changing) and do not provide sufficient heat for use in cold regions. Electric units can also distribute heat unevenly, making it too warm in some areas of the greenhouse and too cold in others. Placing a heater at each end of the greenhouse can help. If you use an electric heater, be sure the fan doesn’t blow warm air directly on the plant leaves; they may scorch.

In most climates, an electric heater with an automatic thermostat will be sufficient to protect tender plants on cold nights. Electricity is an expensive heating option, however, so it’s best reserved for moderate heating needs.

Gas heaters usually cost more than electric and most areas require that a licensed professional hook them up, but heating bills will be lower than if you use an electric heater. Gas heaters operate much like a furnace: a thermostat turns on the heat when the temperature drops below its setting. You can help to distribute the heat by using a fan with the heater. If you plan to use a gas heater, install the gas line when you’re building the foundation. It is also important to ensure that the heater is vented to the outside and that fresh air is available for combustion. Poor ventilation can cause dangerous carbon-monoxide buildup.

Propane, oil, and kerosene heaters also need to be vented, and if you’re using kerosene, be sure it’s high-grade. Another option is hot-water heating, in which the water circulates through pipes set around the perimeter of the greenhouse under the benches. You can also consider overhead infrared heat lamps and soil-heating cables as sources of heat.

A portable space heater may be all the supplemental heat your greenhouse requires. Use it with caution, and make sure yours shuts off automatically if it overheats or is knocked over.

Calculating Heat Needs

Heat is measured in British thermal units (Btu), the amount of heat required to raise one pound of water 1 degree Fahrenheit. To determine how many Btu of heat output are required for your greenhouse, use the following formula.

Area (the total square footage of the greenhouse panels) × difference (the difference between the coldest nighttime temperature in your area and the minimum nighttime temperature required by your plants) × 1.1 (the heat-loss factor of the glazing; 1.1 is an average) equals Btu.

Calculate the area by multiplying the length by the height of each wall and roof panel in the greenhouse and adding up the totals. Here’s an example, using 380 square feet for the greenhouse area and 45 degrees Fahrenheit as the difference between the coldest nighttime temperature (10 degrees Fahrenheit) and the desired nighttime greenhouse temperature (55 degrees Fahrenheit). 380 square feet × 45 × 1.1 = 18,810 Btu.

If the greenhouse is insulated or uses double-glazed glass or twin-wall polycarbonate, you can deduct 30 percent from the total Btu required; if it’s triple-glazed, deduct 50 percent. You can deduct as much as 60 percent if the greenhouse is double-glazed and attached to a house wall.

Oil, gas, kerosene, and other fuel-operated heaters must be vented to the outside and have a source of fresh air for combustion.

Conserving Heat

On cold, cloudy days and at night, solar heat is lost. Even if you have supplemental heating, holding onto that heat is essential to maintaining an optimal climate. Insulating the greenhouse and making use of heat sinks are the most effective means of conserving heat, but don’t overlook heat thieves such as cracks and gaps. Be sure the glazing is tight, and seal any opening that lets in cold air.

If you built a concrete foundation, it may have polystyrene board installed between the concrete and the soil. Concrete rapidly loses heat if the ground around it is cold, and polystyrene insulation helps to reduce this heat loss. You can use polystyrene board or bubble insulation (similar to bubble wrap used for shipping) to temporarily insulate the walls of the greenhouse. Simply attach the material to the greenhouse frame beneath the benches before winter and remove it in the summer. You can also insulate the greenhouse from the outside. Plant low-growing plants around the foundation, or prop hay bales or burlap bags filled with dry leaves against the walls.

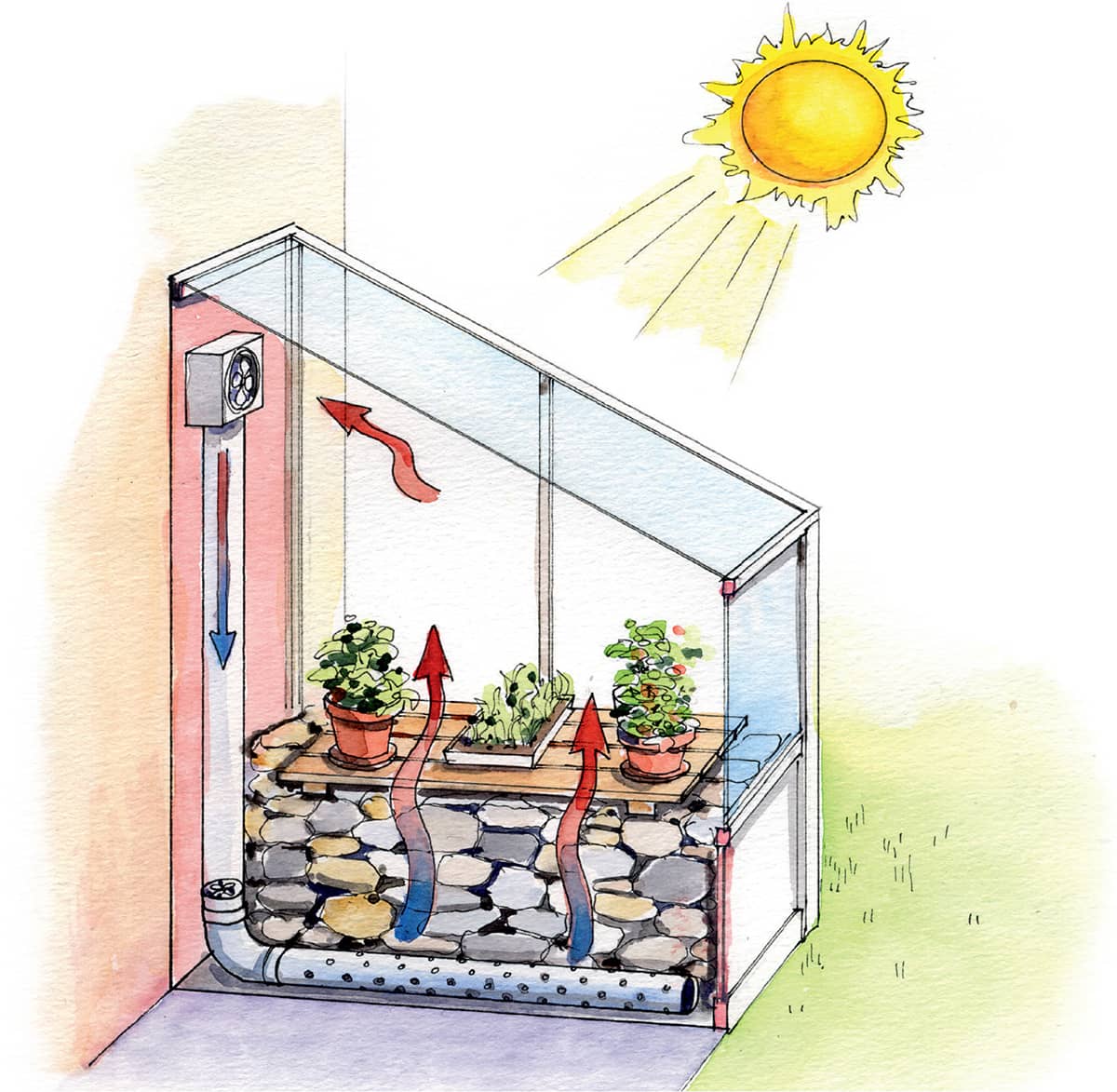

Heat Sinks

Heat sinks absorb solar energy during the day and radiate it back into the greenhouse at night. Stone, tile, and brick floors and walls are good collectors of heat, but to be really effective, they should be insulated from underneath. Piles of rocks can act as heat sink, but the best option is a blue- or black-painted barrel or drum full of water. Place a few of them around the greenhouse. If you have an attached greenhouse, painting the house wall a dark color can cause it to radiate solar heat back into the greenhouse at night. A light-colored wall, on the other hand, can help reflect heat and light back into the greenhouse during the day.

This heat sink system uses solar energy to heat the greenhouse. Air heated by the sun is drawn in by the fan and blown into the rock pile, which also absorbs solar heat. Heat is radiated back into the greenhouse after the sun goes down.

A heating and cooling thermostat is perhaps the most important greenhouse control device. The thermostat will control heat sources and automatic ventilaters to cool the greenhouse when temperatures climb into the danger zone for overheating plants.

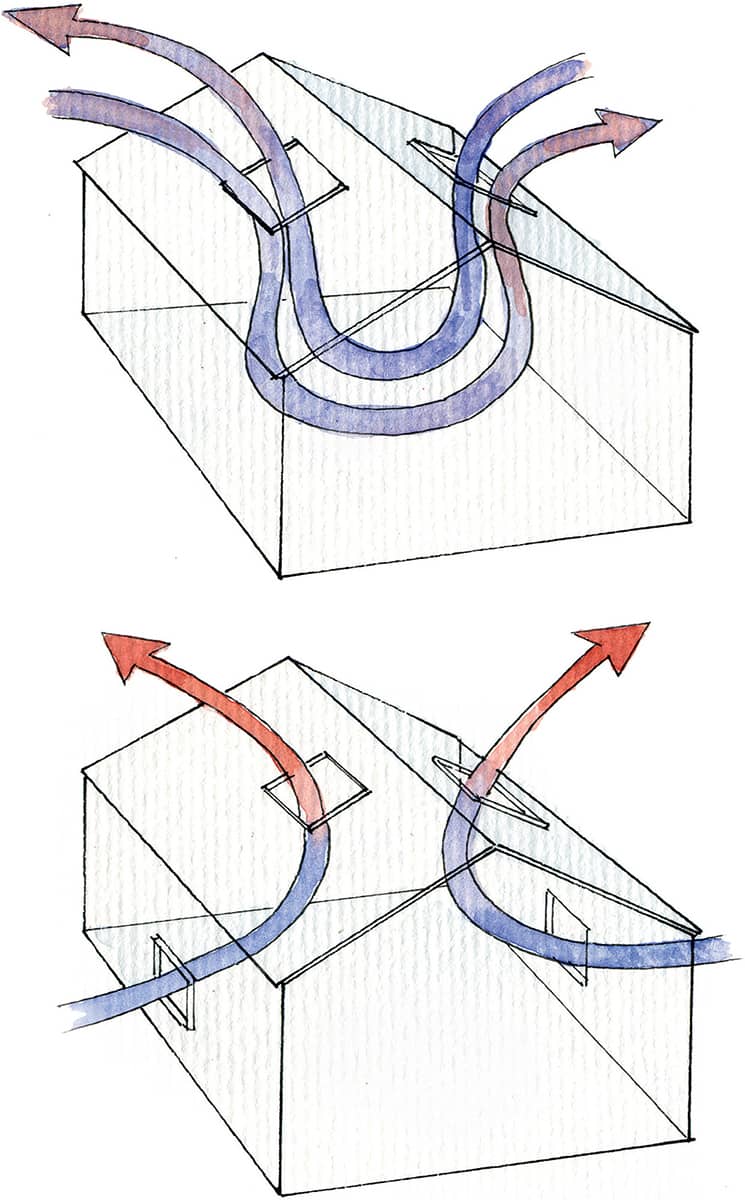

Ventilation

Whether your plants thrive depends on how well you control their environment. Adequate sunlight is a good start, but ventilation is just as important. It expels hot air, reduces humidity, and provides air circulation, which is essential even during winter to move cold, stagnant air around, keep diseases at bay, and avoid condensation problems. You have two main options for greenhouse ventilation: vents and fans.

Because hot air rises, roof vents are the most common choice. They should be staggered on both sides of the ridgeline to allow a gentle, even exchange of air and proper circulation. Roof vents are often used in conjunction with wall vents or louvers. Opening the wall vents results in a more aggressive air exchange and cools the greenhouse much faster than using roof vents alone. On hot days, you can open the greenhouse door to let more air inside. Also consider running small fans to enhance circulation.

Vents can be opened and closed manually, but this requires constant temperature monitoring, which is inconvenient and can leave plants wilting in the heat if you are away. It’s far easier—and safer—to use automatic vent openers. These can be thermostat-controlled and operated by a motor, which turns on at a set temperature, or they can be solar-powered. Unlike thermostat-controlled vent openers, which require electricity, solar-powered openers use a cylinder filled with wax, which expands as the temperature rises and pushes a rod that opens the vent. When the temperature drops, the wax shrinks and the vent closes. How far the vent opens is dictated by temperature: the higher the temperature, the wider the vent opens to let in more air.

A fan ventilator is a good idea if you have a large greenhouse. The fan is installed in the back opposite the greenhouse door, and a louvered vent is set into the door wall. At a set temperature, a thermostat mounted in the middle of the greenhouse activates the fan, and the louvered vent opens. Cool air is drawn in through the vent, and the fan expels the warm air. The fan should be powerful enough to provide a complete air exchange every 1 to 1.5 minutes.

Automatic openers sense heat buildup and open vents. Some openers are controlled by standard thermostats, while others are solar-powered.

Venting your greenhouse– Installing at least one operable roof vent on each side of the ridgeline creates good air movement within the structure. Adding lower intake vents helps for cooling. Adding fans to the system greatly increases air movement.

Cooling

Although vents and fans are the first line of defense when the temperature inside the greenhouse starts to climb, other cooling methods such as misting, humidifying, evaporative cooling, and shading can also help to maintain the ideal growing environment. Cooling is crucial during summer, but it can be just as important on a sunny winter day.

Shades

By blocking direct sunlight, shades protect plants from sunburn and prevent the greenhouse from getting too hot. They can be installed on the exterior or hung from cables inside the greenhouse. Both methods block the sun, but only exterior shades prevent solar energy from penetrating the glazing, thereby keeping the air inside the greenhouse cooler.

When choosing shades, be sure they are UV stabilized for longevity.

Two types of shades are available: cloth and roll-up. Shade cloth is usually woven or knitted from fiberglass or polyethylene and is available in many colors, although green, black, gray, and white are most common. You can also find shade cloth in silver, which, like white, reflects heat and sunlight and keeps the greenhouse cooler than darker colors. Shade cloth also varies in density, usually from 20 percent to 80 percent. The higher the density of the cloth, the more light it blocks (60 percent density blocks 60 percent of the light). Be careful when choosing shade density; too little light will slow plants’ growth.

Shade cloth can be simply thrown over the greenhouse and tied down when shading is needed, but this hampers airflow through the vents (unless you cut the cloth to size and install it in sections). Better ventilation is achieved by suspending the cloth 4 to 9 inches above the exterior glazing. Be sure the vents are open when you do this. Greenhouse shade suppliers can provide framework kits.

Roof shades, along with vents, help prevent a greenhouse from overheating in direct sunlight. Here, a combination of circulating fans and cloth shades mounted on the interior of the south-facing glass helps protect plants.

Louvered and roll-up shades help to block the sun in this greenhouse.

In addition to cloth, roll-up greenhouse shades may be constructed from aluminum, bamboo, or wood. They are convenient because you roll them up when they’re not needed, and they last longer than shade cloth, but they are more expensive.

Evaporative Coolers

Evaporative coolers (also called swamp coolers) cool the air by using a fan to push or pull air through a water-saturated pad. A portable cooler might be sufficient for a small greenhouse; larger greenhouses will benefit from a unit cooler placed outside. Used when the humidity outside is less than 40 percent, these units draw dry outside air through the saturated pad, where it is cooled. The air travels through the greenhouse and exits via a vent on the opposite side. It’s a good idea to use an algaecide with these coolers.

Liquid Shading

Some greenhouse gardeners choose to paint liquid-shading compounds (sometimes called whitewashing) over the outside glazing. These compounds are inexpensive and easy to apply, but they can be unattractive and tend to wash off in the rain. Liquid shading can be thinned or layered to the level desired, and the residue can be brushed off at the end of summer. (It is often almost worn off by that point anyway.) Some liquid-shading compounds become transparent during rainy weather to let in more light and then turn white when they dry.

Roof vents that are triggered to open automatically by sensor alerts are far and away the most important component of a greenhouse cooling system. But additional cooling devices may be necessary.

Workbenches & Storage

Almost any greenhouse can benefit from the right workbench in the right area. But choose carefully, because the weight and messiness of some plants means only certain workbenches will do.

How you lay out benches depends on your needs and the size of your greenhouse. Most average-size greenhouses can accommodate a bench along each wall, with an aisle down the middle for access. If you have enough space along one endwall, you can install more benches to create a U shape. Another option is to arrange the benches in a peninsula pattern. Shorter benches are set at right angles to the outside walls, with narrow aisles in between, leaving space for a wider aisle down the middle. You can also use a single, wider bench along a side wall and leave space for portable benches and taller plants against the other wall. A larger greenhouse can accommodate three benches with two aisles.

Regardless of the layout you choose, it’s best to run workbenches east to west so plants receive even light distribution throughout the day. Use the space as efficiently as possible, and don’t inadvertently block the door. Allow enough room in the aisles to move around comfortably; make them wider if you need to accommodate a garden cart or wheelbarrow. Set benches about 2 inches from the greenhouse walls to provide airflow, and avoid placing benches near any heat source.

Bench width is determined by the length of your reach, so if you are short, you may want benches to be narrow. The same concept applies to height: although the average bench is about 28 to 32 inches, yours can be higher or lower to suit your height and reach. (If they need to be wheelchair-accessible, lower them even more.) If you have access to benches from both sides, you can double their width.

Several options are available for bench tops. Wood slats are sturdy and attractive, and they provide good drainage and airflow. Use pressure-treated or rot-resistant wood, such as cedar, keeping in mind that cedar benches can be expensive. Wire mesh costs less, is low-maintenance, and also provides good airflow, but be sure that it is strong enough to support heavy plants. Plastic-coated wire-mesh tops are available. These are similar to (if not the same as) the closet shelving found in home stores. Usually white, they have the advantage of reflecting light within the greenhouse.

Sturdy benches that are easy to clean and withstand moisture are a critical part of a greenhouse that’s pleasant to work in.

For space efficiency, potting benches can double as storage containers. Here, the potting benches include spaces for mixing and storing soils for potting. Slatted covers make it easy to keep the bench-tops tidy.

You can also choose solid tops made of wood, plastic, or metal. Solid wood tops should be made from pressure-treated wood, and metal tops should be galvanized to prevent rust. Solid tops provide less air circulation than slatted or mesh tops, but they retain heat better in winter and are necessary if you use a capillary-mat watering system.

The greenhouse framing material will determine whether you can install shelves. Shelves can easily be added to a wood-framed greenhouse, and many aluminum greenhouse kit manufacturers provide predrilled framing, along with optional accessories for installing shelves. Keep in mind that even if shelves are wire mesh, they can cast shade onto the plants below.

If you plan on potting inside the greenhouse, you can use part of the benches or dedicate a separate space for a potting bench in a shady corner or along an endwall. For convenience, consider building or buying a potting tray that you can move around and use as needed.

Unless you have a separate place to store tools and equipment, you’ll need to find room for them in the greenhouse. To determine how much space you’ll need, first list all of the equipment necessary to operate the greenhouse: everything from labels, string, and gardening gloves to bags of soil, pots, trash cans, and tools. If you will use harmful chemicals, be sure to include a lockable storage area.

Just as in your home, finding storage space in the greenhouse can be a challenge. Look first to shady areas. If the greenhouse has a kneewall, the area under the benches can provide a good deal of storage space. Shelves can also provide storage space for lightweight items. Be creative and make efficient use of any area where plants won’t grow to create accessible yet tidy storage for equipment.

Potting Materials

If you’re a container gardener, you are already familiar with the vast array of pots available at garden centers. For greenhouse gardening, however, pot choices are narrowed to two types: terra cotta and plastic.

Terra cotta pots are attractive and heavier than plastic, which means they are less likely to be knocked over. In addition, they are porous—because water evaporates through the clay, the risk of overwatering is lower. However, you will have to water plants more often and clean the pots regularly to remove deposits caused by minerals from water and soil leaching through the sides. Glazed terra cotta pots hold moisture better than unglazed pots and don’t show mineral deposits. Terra cotta pots are more expensive than plastic pots.

Practical and inexpensive, plastic pots hold moisture better than terra cotta pots, so you don’t have to water plants as often. Gardeners who plan to start seeds and propagate plants often use plastic trays, flats, and cell packs, although peat pots, cubes, and plugs are also available for starting seeds.

Terra cotta containers are preferable if your plants will live in the pot permanently. If you are only starting plants for transplant, inexpensive plastic pots and trays are a good choice.

Easy-to-Build Greenhouses

Some greenhouse designs are so simple that construction requires only a weekend or two. The foundation can be an anchored wooden frame or, for a more permanent structure, a concrete base.

Hoophouse

Economical and versatile, a hoop-style greenhouse (also called a hoophouse or a quonset house) is constructed of PVC or metal pipes that are bent into an inverted U shape, attached to a base, and connected at the top by a ridgepole. A hoophouse is usually covered with plastic sheeting. A door can be set at one end, and there may be an exhaust fan or flap vent that can be rolled up for ventilation. Because the hoop greenhouse is lightweight, it is not a good choice in areas with strong winds. (For instructions on building a hoophouse, see here to here.)

A hoophouse is a simple greenhouse made by wrapping clear plastic over a series of U-shape frames. See here.

A-frame Greenhouse

An A-frame greenhouse is small and lightweight and can be made of wood or PVC. A series of A-frames is attached to a wood base and covered with plastic sheeting or rigid plastic panels, such as polycarbonate or fiberglass. Because of the steep pitch of the roof, this type of greenhouse easily sheds rain, snow, and leaves and provides more headroom than a hoop greenhouse. It can also be portable.

An A-frame greenhouse is a structure that is both incredibly simple and very stable. It’s a great starter option for novice greenhouse gardeners.

Greenhouse Kits

No matter what kind of greenhouse you have in mind, chances are you can find a kit to match your vision. Dozens of companies offer kits in diverse styles, sizes, materials, and prices. Some offer door options—sliding versus swinging doors, for example, with and without locks and screens. Some offer glazing combinations, such as polycarbonate roof panels with glass walls. And some even offer extension kits for certain models, so you can add onto your greenhouse as your space requirements grow.

Kit basics usually include framing, glazing panels, vents (though usually not enough—it’s a good idea to buy extras), and hardware. A good kit will come predrilled and precut, so you only need a few tools to assemble it. Most kits do not include the foundation, benches, or accessories.

Be sure the kit you choose comes with clear, comprehensive instructions and a customer-service number for assistance. Also ensure that it complies with your local building codes and planning regulations. Depending on the company, shipping may be included in the price. Because kits are heavy, shipping can be expensive; be sure to figure it and the cost of the foundation, benches, all necessary accessories, and the installation of utilities into your budget.

This kit greenhouse has an aluminum frame and polycarbonate panels. It features sliding doors and a roof vent. With nearly 200 square feet of floor space, it was a good bargain at around $800. See here.

Cold Frames

An inexpensive foray into greenhouse gardening, a cold frame is practical for starting early plants and hardening off seedlings. It is basically a box set on the ground and topped with glass or plastic. Although mechanized models with thermostatically controlled atmospheres and sashes that automatically open and close are available, you can easily build a basic cold frame—or several, in a range of sizes (See here). Just be sure to make the back side of the frame about twice the height of the front so that the glazing can be slanted on top. Also ensure that the frame is tall enough to accommodate the ultimate height of the plants growing inside. The frame can be made of brick, plastic, wood, or other materials, and it should be built to keep drafts out and the soil in. Most important, the soil inside must be fertile, well tilled, and free of weeds.

If the frame is permanently sited, position it to receive maximum light during winter and spring and to offer protection from wind. An ideal spot is against the wall of a greenhouse or another structure. Ventilation is important; more plants in a cold frame die from heat and drought than from cold. A bright March day can heat a cold frame to 100 degrees Fahrenheit (38 degrees Celsius), so be sure to monitor the temperature inside, and prop up or remove the cover when necessary. On cold nights, especially when frost is predicted, cover the box with burlap, old quilts, or fallen leaves for insulation.

A prefabricated cold frame such as this offers many benefits, including an easy-to-use flip top, white plastic glazing that diffuses light, and an attractive appearance.

Sunrooms

A greenhouse can certainly satisfy the desire to grow a profusion of plants year-round, but it’s not everyone’s cup of tea. Even the most avid gardener will agree that operating and maintaining a greenhouse requires a major commitment—in a greenhouse, the plants depend solely on you for their well-being. The sunroom, on the other hand, allows you to surround yourself with flowers and plants in a sunny, light-filled room that is designed primarily for your comfort.

Like the greenhouse, the sunroom’s roots are found in the orangeries and conservatories built on the grand estates of Europe. In the nineteenth-century conservatory, fashionable women gathered under the glass in exotic, palm-filled surroundings for tea. The twenty-first-century garden room invites us to do the same, in a comfortable interior environment from which we can appreciate the outdoors year-round. Large windows and doors open onto the terrace or garden. A high roof, which might be all glass, lets in abundant natural light. Decorative architectural features announce that this place is different from the rest of the house—separate, but in harmony. Like the conservatories of old, sunrooms can be used for growing plants and flowers indoors, but they are just as often used as sitting rooms, from which to admire the plantings outside the windows.

The sunroom can be a grand conservatory—an ornamented, plant-filled glass palace attached to an equally grand home. Or it can be a modest room containing little more than a few potted plants and a comfortable reading chair. Grand or modest, the sunroom is neither wholly of the house nor of the garden; it is a link between the two, a place in which you can feel a part of the garden but with all of the comforts of home.

Like greenhouses, sunrooms can be as simple or as elaborate as your budget and style will allow. This sunroom blends beautifully with the house.

Greenhouse Styles

When choosing a greenhouse, consider the benefits and disadvantages of each style. Some offer better use of space, some better light transmission; others offer better heat retention, and some are more stable in strong winds. Keep in mind how you plan to use the greenhouse—its size and shape will have an impact on the interior environment.

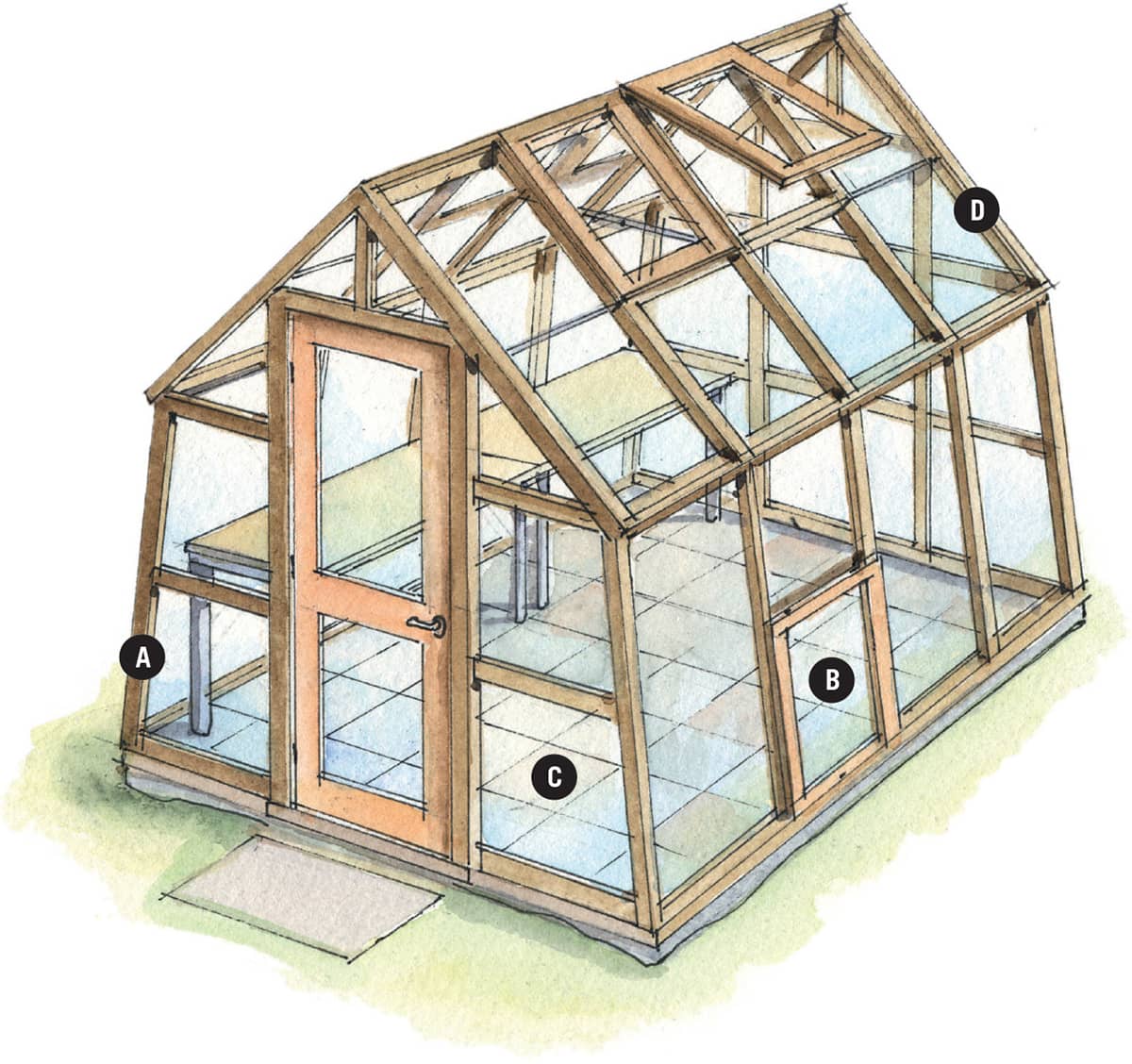

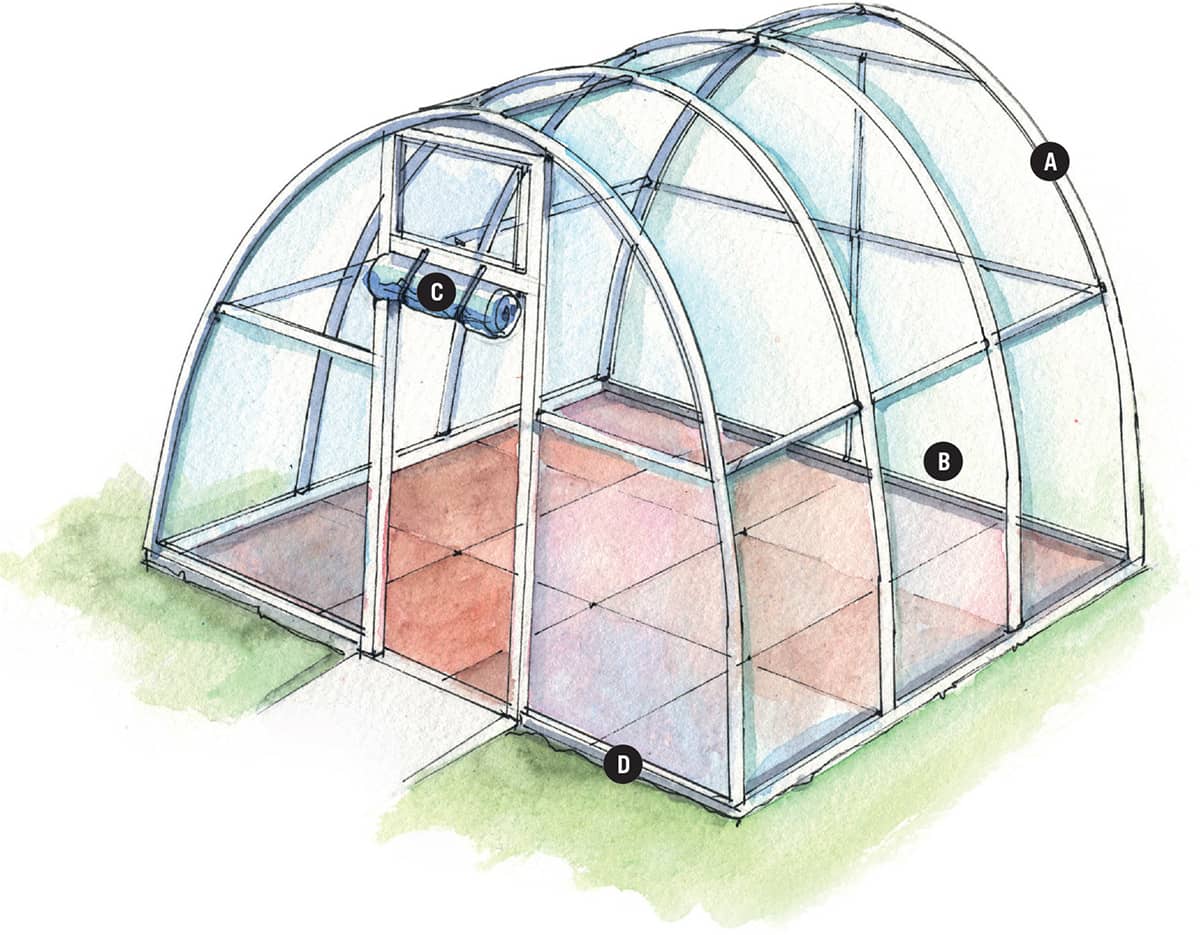

Traditional Span

A Ventilating roof windows

B High gable peak provides headroom

C 45° roof angle encourages runoff

D Solid kneewalls block wind, provide impact protection, and allow insulation

This type of greenhouse has vertical side walls and an even-span roof, with plenty of headroom in the center. Side walls are typically about 5' high; the roof’s central ridge stands 7 to 8' above the floor. This model shows a low base wall, known as a kneewall, but glass-to-ground traditional-span houses are also widely available. Kneewalls help to conserve heat but block light below the benches; glass-to-ground houses suffer more heat loss but allow in more light.

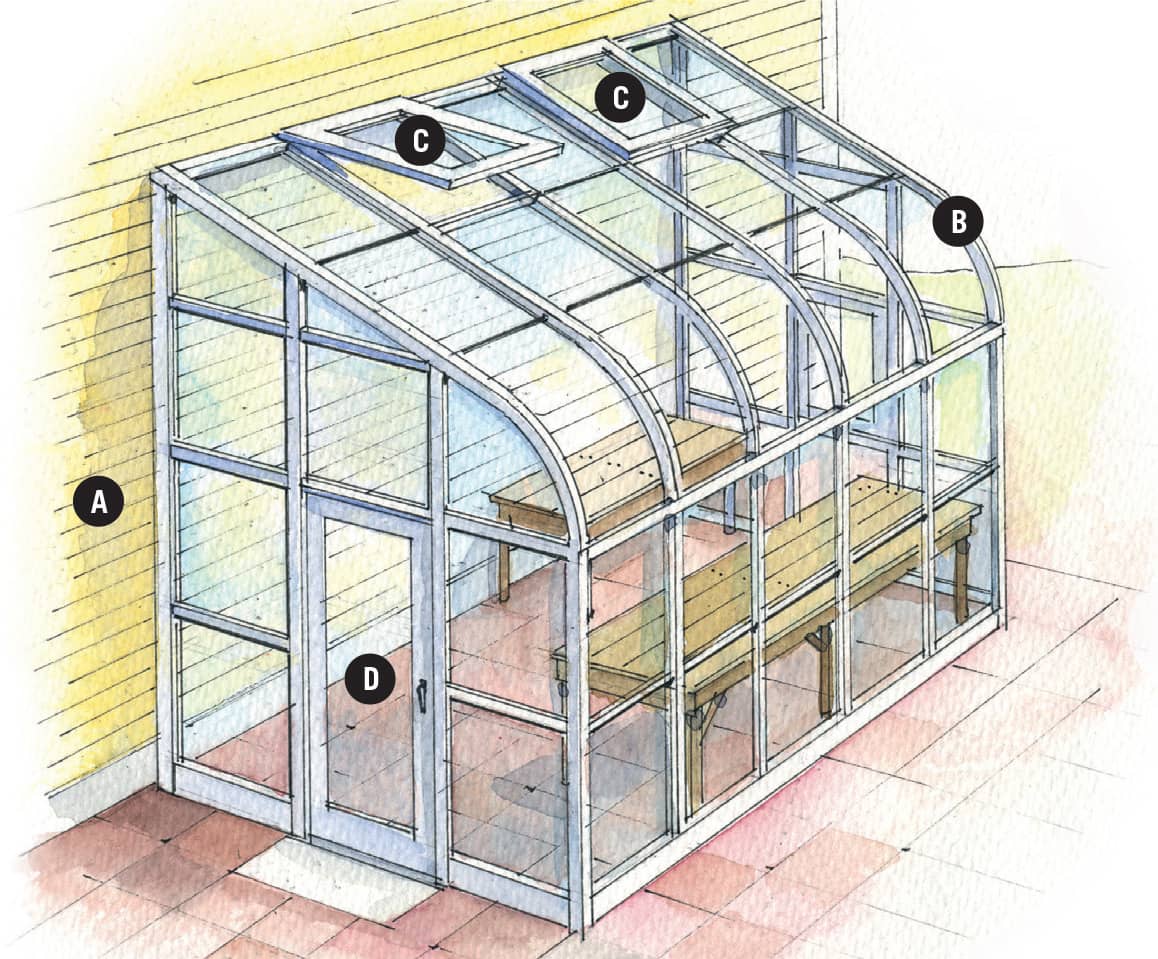

Lean-To

A Adjoining house provides structure and heat

B Aluminum frame is lightweight but sturdy

C Roof vents can be set to open and close automatically

D Well sealed door prevents drafts and heat loss

Because it is attached to the house, a lean-to absorbs heat from the home and offers easy access to utilities. This model shows curved eaves, a glazed roof, and glass-to-ground construction. Lean-tos can be built on kneewalls to provide more headroom and better heat retention than glass-to-ground styles. Sinking the foundation into the ground about 2 to 3' can conserve even more heat.

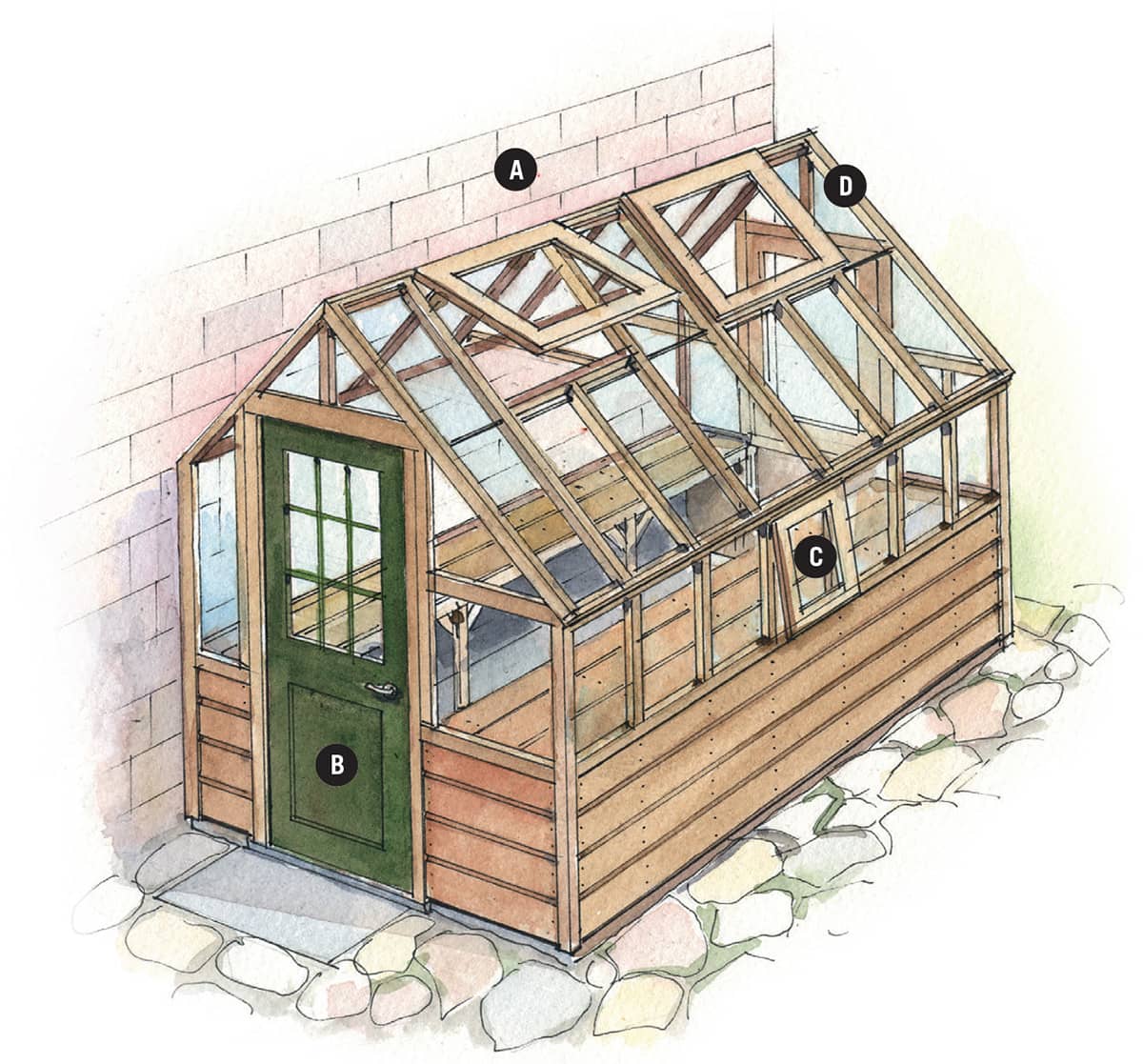

Three-Quarter Span

A Adjoining house provides shelter

B Half-lite door insulates but allows some light in

C Operating side vent

D Gable creates headroom

Also attached to the house, this type of greenhouse offers the benefits of a lean-to with even more headroom and better light transmission (though it offers less light than a freestanding model). Because of the additional framing and glazing, this style is more expensive to build than a traditional lean-to.

Dutch Light

A Tapered sidewalls encourage condensation to run off

B Lower side vent encourages airflow

C Tile floor retains heat

D Roof angle minimizes light reflection

Especially suitable for low-growing border crops, such as lettuce, this design has sloping sides that allow maximum light transmission. However, the large panes of glass, which may be 30 by 59", are expensive to replace.

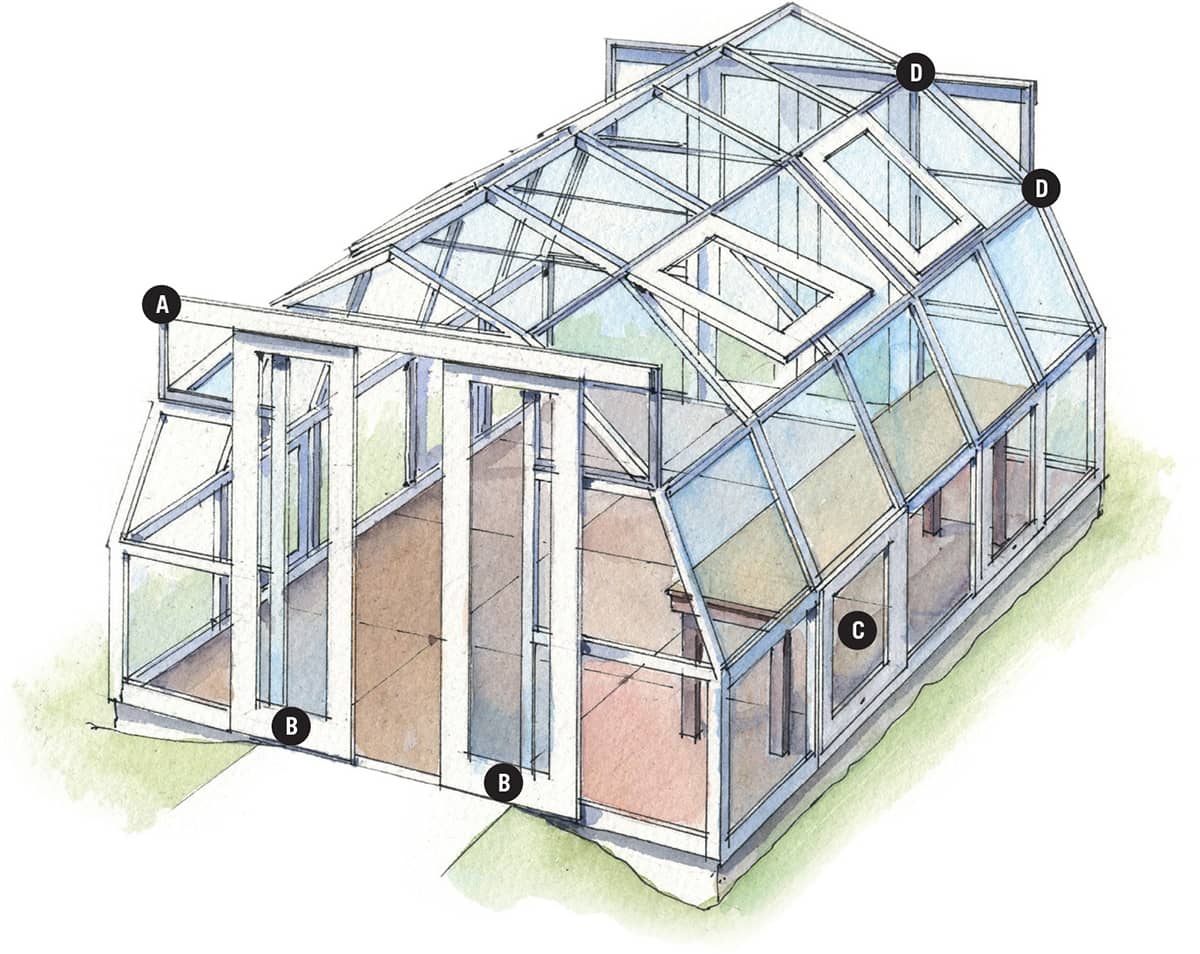

Mansard

A Full-width door frame

B Sliding doors can be adjusted for ventilation

C Lower side vents encourage airflow

D Stepped angles ensure direct light penetration any time of day or year

The slanting sides and roof panels that characterize the mansard are designed to allow maximum light transmission. This style is excellent for plants that need a lot of light during the winter.

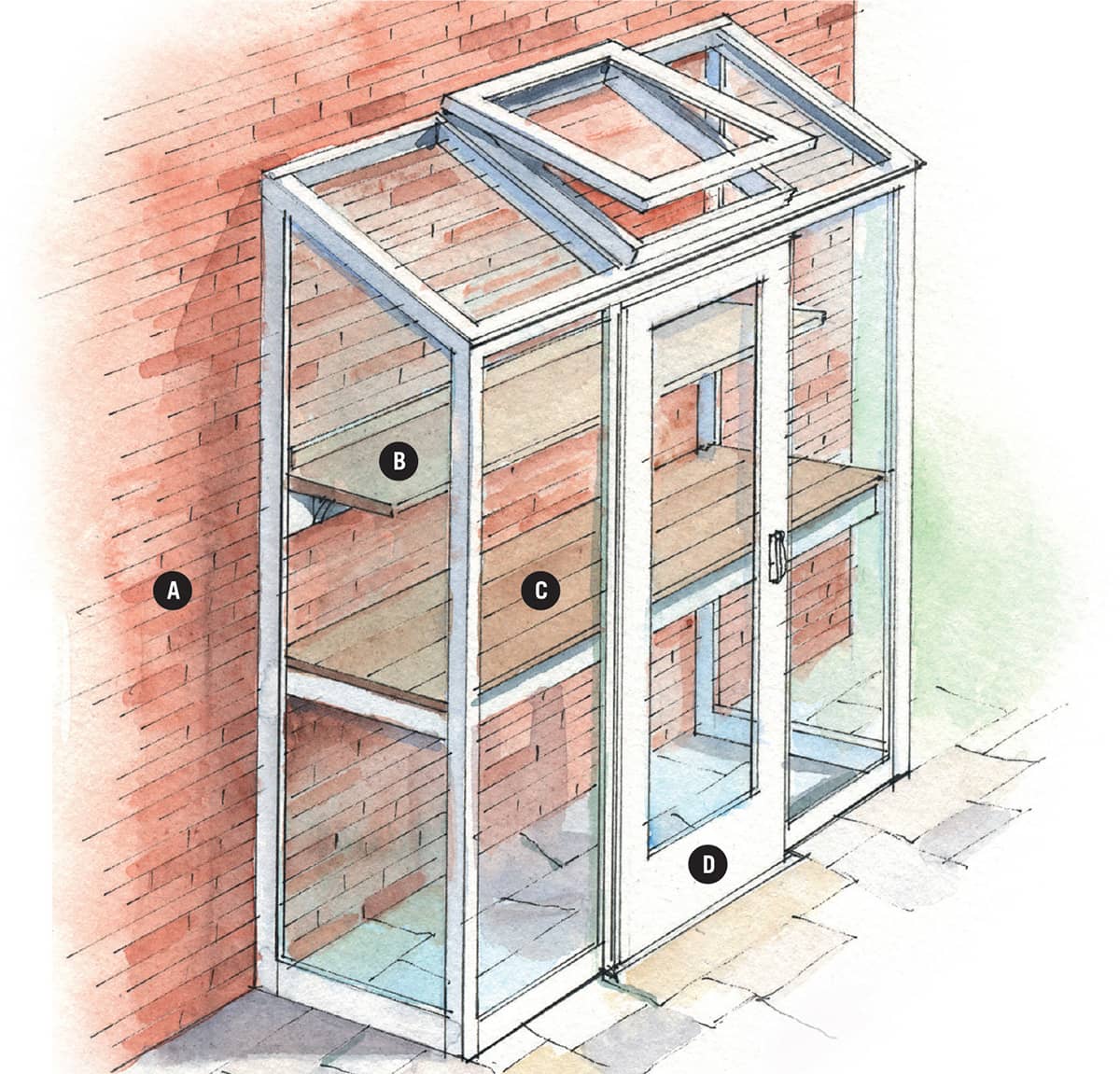

Mini-Greenhouse

A Brick wall retains heat

B Upper shelf does not block airflow

C Full-depth lower shelf creates hot spot below

D Full-lite storm door

A relatively inexpensive option that requires little space, this greenhouse is typically made of aluminum framing and can be placed against a house, a garage, or even a fence, preferably facing southeast or southwest, to receive maximum light exposure. Space and access are limited, however; and without excellent ventilation, a mini-greenhouse can become dangerously overheated. Because the temperature inside is difficult to control, it is not recommended for winter use.

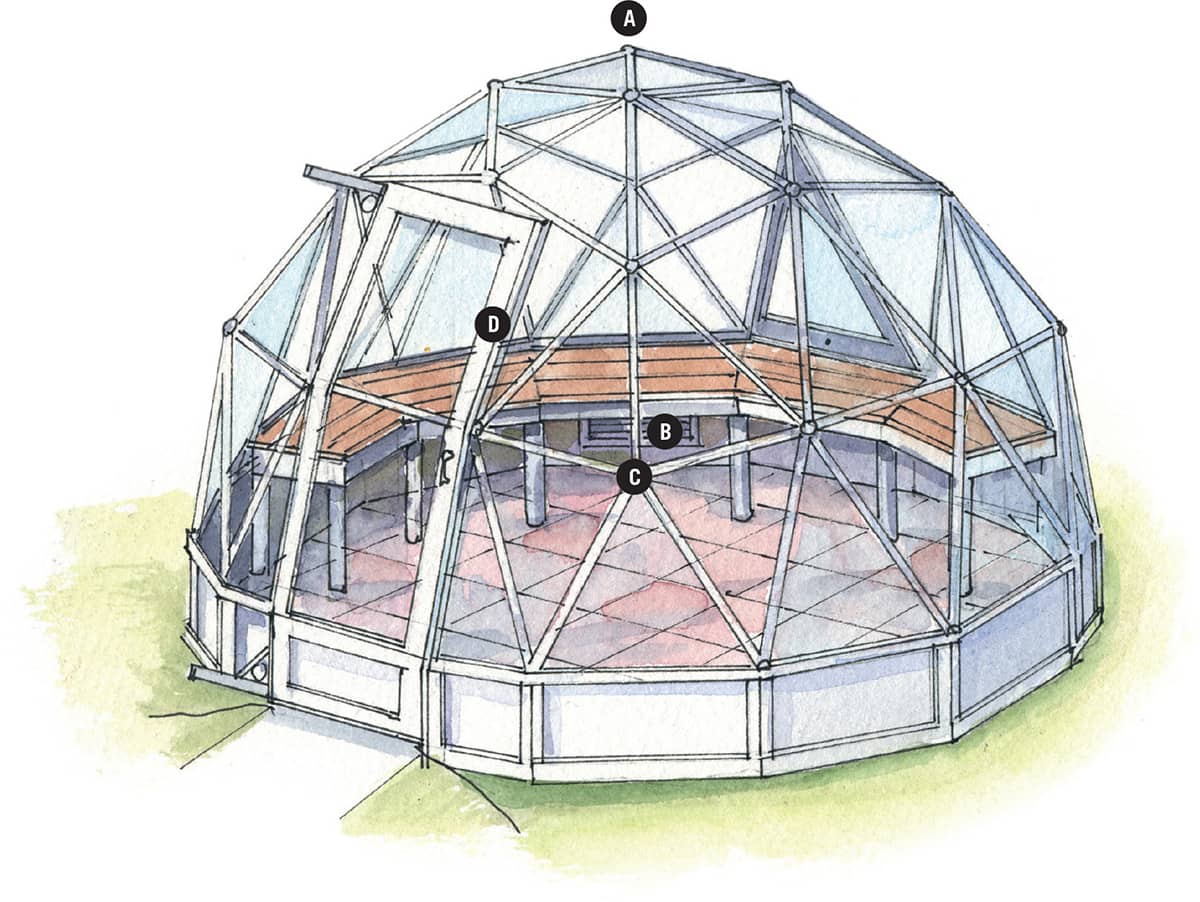

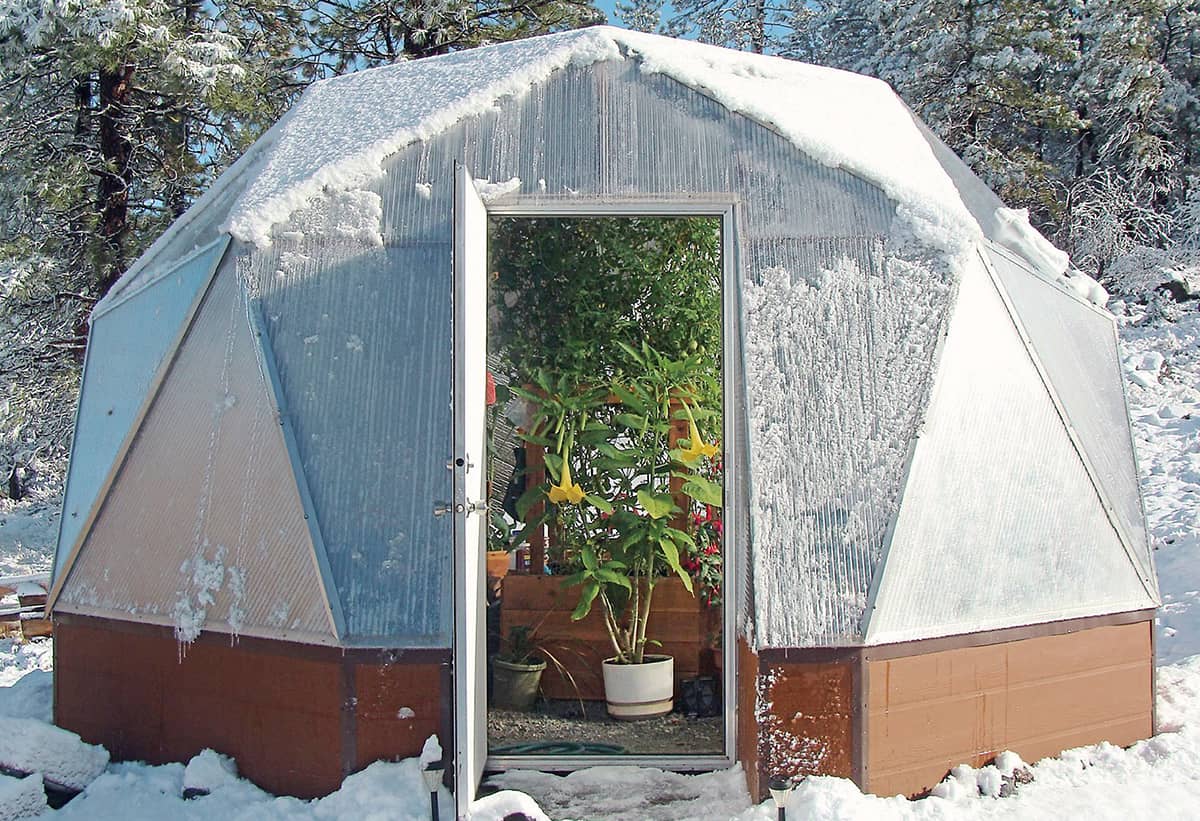

Dome

A Geometric dome shape is sturdy and efficient

B Louvered air intake vent

C Gussets tie structure together

D Articulated door is visually interesting (but tricky to make)

This style is stable and more wind-resistant than traditional greenhouses, and its multi-angled glass panes provide excellent light transmission. Because of its low profile and stability, it works well in exposed locations. However, it is expensive to build and has limited headroom, and plants placed near the edges may be difficult to reach.

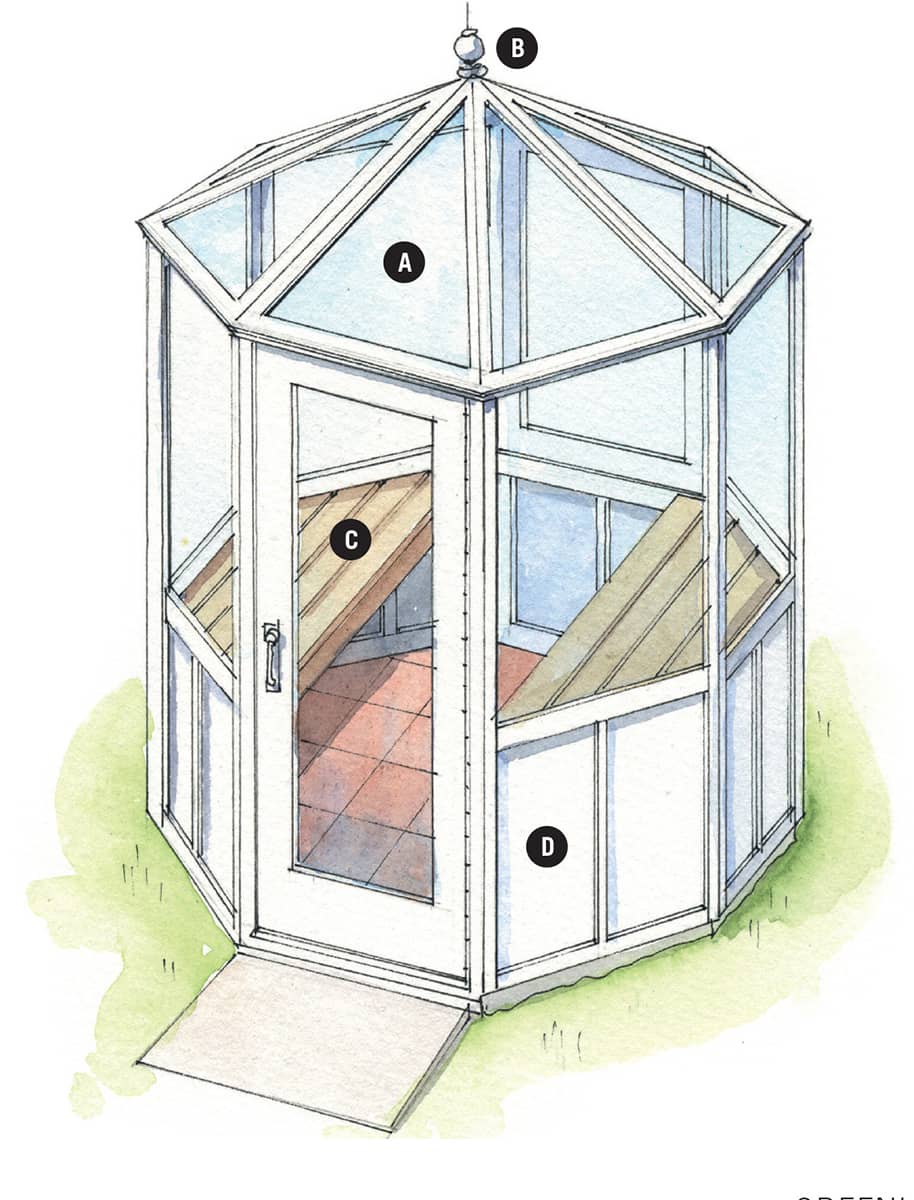

Polygonal

A Triangular roof windows meet in hub

B Finial has Victorian appeal

C Built-in benches good for planters or for seating

D Lower wall panels have board-and-batten styling

Though it provides an interesting focal point, this type of greenhouse is decorative rather than practical. Polygonal and octagonal greenhouses are typically expensive to build, and space inside is limited.

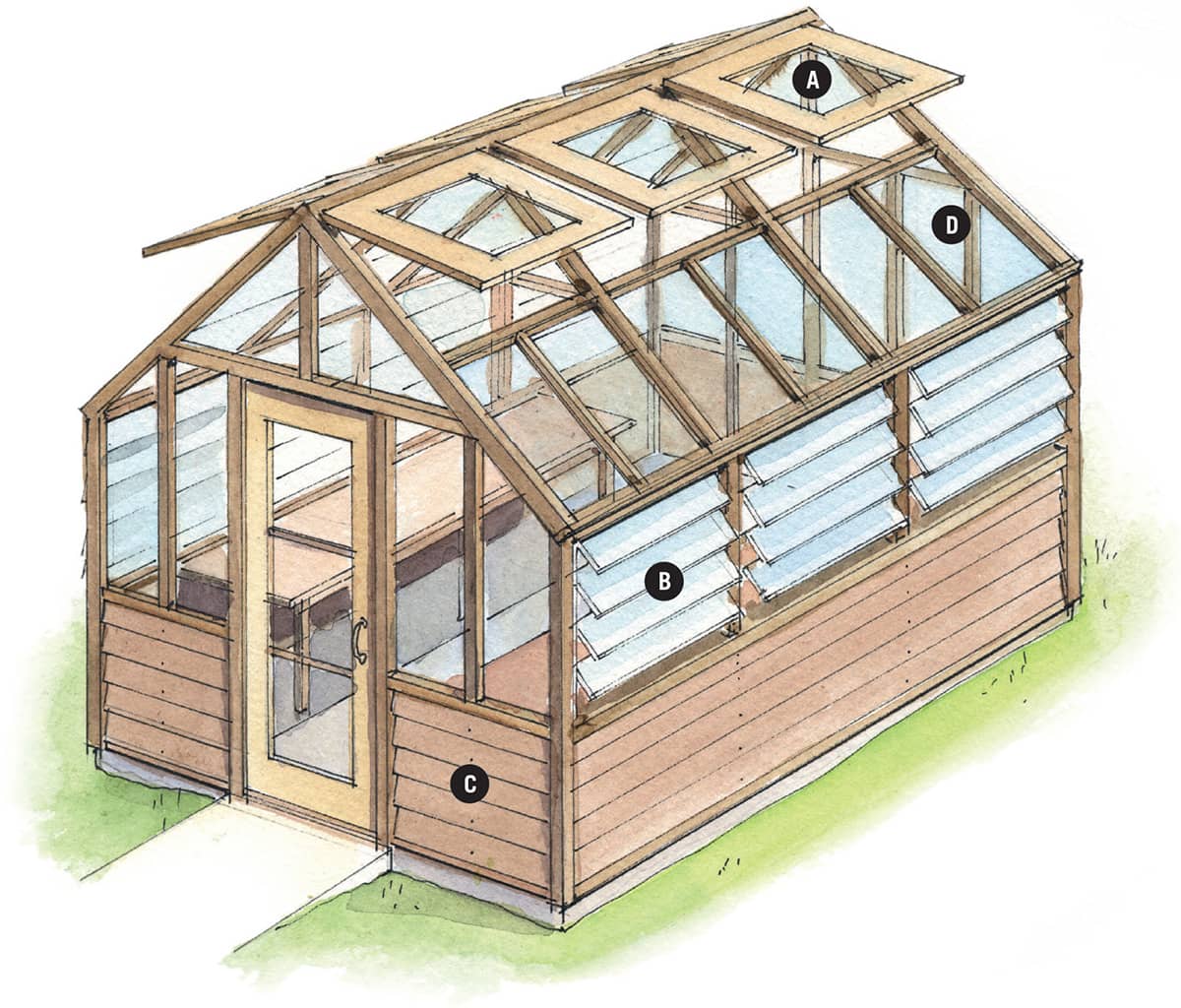

Alpine House

A Banks of venting windows at both sides of peak

B Adjustable louvers for air intake

C Cedar siding on kneewall has rustic appeal

D Fixed roof windows lend stability

Specifically designed for plants that normally grow at high elevations and thrive in bright, cool conditions, this alpine house is unheated and has plenty of vents and louvers for maximum ventilation. Doors and vents are left open at all times (except in winter). Many rock-garden plants—edelweiss, sedum, and gentian, for example—appreciate the alpine house environment.

Hoophouse

A Bendable PVC tubes provide structure

B 4-mil plastic sheeting is very inexpensive glazing option

C Roll-up door

D Lightweight base makes hoophouse easy to move

Made of PVC or metal framing and plastic glazing, this lightweight, inexpensive greenhouse is used for low-growing crops that require minimal protection from the elements. Because it does not provide the warm conditions of a traditional greenhouse, it is designed mainly for extending the growing season, not for overwintering plants. Ventilation in this style can be a problem, so some models have sides that roll up.

Conservation Greenhouse

A High peak for good headroom

B Louvered wall vents

C Sturdy aluminum framing

D Broad roof surface for maximum heat collection

With its angled roof panels, double-glazing, and insulation, the conservation greenhouse is designed to save energy. It is oriented east-to-west so that one long wall faces south, and the angled roof panels capture maximum light (and therefore heat) during the winter. To gain maximum heat absorption for the growing space, the house should be twice as long as it is wide. Placing the greenhouse against a dark-colored back wall helps to conserve heat—the wall will radiate heat back into the greenhouse at night.

Gallery of Greenhouses

For such a basic, utilitarian structure, there is an astounding diversity of greenhouse styles. Some are purely functional, while others are over-the-top gorgeous. That’s why, once you’ve made all the practical decisions of how big it will be, where you’ll put it, what services you’ll need, and what foundation it will go on, you’ll still have plenty of options to choose from based purely on looks.

The traditional glass greenhouse is giving way to modern versions with synthetic panels that are often opaque, diffusing light and sparing plant leaves from burning. But the forms of the greenhouse structure haven’t really changed. You can choose a traditional gabled construction, a slant-sided Dutch style, or a thoroughly modern geodesic dome. You’ll find a range of options covered in the pages that follow. Use these as inspiration for your ultimate decision.

Go grand when you want to marry traditional style to a stunning landscape. If money is no object, your greenhouse can be a jaw-dropping feature that creates a centerpiece for your landscape. This traditional greenhouse features a steel frame, glass glazing, and the time-honored roof crest that is not only a distinctive visual feature but also keeps birds from perching on the ridge and fouling the roof’s panels.

Grow in modern style with a high-end prefab shed greenhouse. This backyard stunner is sold as a kit but looks custom. It includes operable vent windows, and the footprint lends itself to many different greenhouse workspace configurations. Keep in mind that a greenhouse can be a backyard focal point as well as a utility building.