“HAVING FAITH” IN PÉTAIN (1940-1944)

IT IS believed that close to forty million French people—the entire population of France—supported Philippe Pétain and his Vichy regime in the summer of 1940. When Pétain came to power on June 16, after a grim month-long struggle against German forces, in which over ninety thousand Frenchmen lost their lives, he was widely perceived as a national hero. Pétain’s quick reassurances to the citizens of France that the uncertainties of the Phoney War with Germany were over, that the social and political instability of the 1930s had come to an end, and that France was on its way to recovery fell upon eager ears. The will to believe in his leadership was palpable in all corners of the population and signified an abiding desire for national healing after years of perceived decadence. In the following weeks, an armistice with Germany was signed, the parliamentary government of the Third Republic was dissolved—along with most of the French Republic’s core principles—and Pétain was named chief of state of Vichy France. During this period, according to Zeev Sternhell, “France changed more radically in a few months than at any other time in its history since the summer of 1789.”1

Even those who initially resisted an armistice with the Nazis respected the stately eighty-four-year-old Pétain, who retained a “remarkable alertness” that belied his age and physical capacities. Looking back at the widespread exhaustion and fear within French society in June 1940, it is not hard to understand why so many were drawn to Pétain’s calm and authoritative presence. As historians have noted of the period just before the armistice, “the French were weary, divided, tense, devoid of all sense of adventure, and reaching out for security and comfort.”2 Although the Germans may have held as little as 10 percent of the country by the time of the armistice, the widespread perception of “inhuman” German might quickly sapped French morale and lent support to capitulation.3 Pétain powerfully addressed his country’s felt needs. When Pétain made his famous pronouncement on taking power—“I give to you the gift of my person”—he underscored the Christlike nature of his efforts.4 Self-sacrifice would describe the tone of his administration, as it had in his days on the battlefield at Verdun. His tenacity in one of the most important battles of World War I had earned him the title “the Victor of Verdun”; his perceived courage on behalf of a defeated country in 1940 would transform him, Joan of Arc-style, into the “Savior of France.” Yet although Pétain’s power would be cloaked in selfless patriotism, and although Vichy ideology would advertise itself in terms of a return to traditional Catholic values, Pétain’s regime was an important first: the first modern dictatorship that France had ever known.

Defeat is a complex phenomenon, one that can produce widely differing responses depending upon how the losers interpret their loss. In The Culture of Defeat: On National Trauma, Mourning, and Recovery, Wolfgang Schivelbusch argues that the French had developed a particular way of coming to terms with military defeat since at least the fall of Napoleon I. Gloom and anxiety about a national humiliation was invariably followed by immediate calls for renewal, for a fresh start. Schivelbusch identifies the specific French term for this process: revanche, understood as both revenge or retaliation and the reestablishment of social equilibrium. Revanche served multiple purposes: while usually directed at the external victor who had conquered France, it could also refer, as it did in 1940, to the internal social elements who had led to France’s defeat. In Third Republic France, revanche functioned “as a political religion, foundational myth, and integrating force.”5 But even with the fall of the Third Republic in the summer of 1940, revanche remained a powerful and mobilizing term for the Pétain regime. André Gide would capture this idea in describing the events leading up to Vichy: “Yes, long before the war, France stank of defeat. She was already falling to pieces to such a degree that perhaps the only thing that could save her was, is perhaps, this very disaster in which to retemper her energies.”6

Pétain immediately strove to acknowledge and interpret the defeatism of his constituents. His explanation for the fall of France seemed remarkably appropriate at the moment of France’s defeat. “Too few allies, too few weapons, too few babies,” he announced in June 1940, at the same moment sounding the call for a revanchist National Revolution.7 Although historians now agree that the blame for France’s defeat lay predominantly with military strategy, at the time of his pronouncement Pétain’s words resonated.8 Finally France could address the internal corruption that had led the nation to its unfortunate pass; finally France could recover from one hundred and fifty years of misguided parliamentary democracy. As the historian Denis Peschanski writes, “Vichy conveys, to begin with, a special idea of defeat. The ideologues of the new regime found their way again by seeking through defeat the possibility of completely remaking French society: utopia from a clean slate.”9 Attacking the now-defunct Third Republic’s views on education, secularization, urbanization, women’s emancipation, and parliamentary rule, Pétain and his administration proposed a wholesale “recovery plan” for the nation based on famille, travail, patrie (family, work, fatherland). “I invite you to an intellectual and moral renewal first of all,” Pétain stated in his famous speech of June 25, 1940, justifying the armistice with Germany. And again on October 11: “We must, tragically, achieve in defeat the revolution which in victory . . . we could not even imagine.”10

Interestingly, Pétain’s idea of revanche was not the expected one, directed at the external enemy who had actually caused France’s defeat: Germany. Although suspicious of Germany from the start, Pétain, according to most of his biographers, felt that German plans for a New Europe might indeed allow France “to regain her status as a major power in Europe and the world.” “Cooperation with Germany,” for Pétain, “was the only possible policy.”11 It helped enormously that the armistice had appeared to guarantee France’s sovereignty, and appearances at this moment were everything. It was in fact the British, not the Germans, who had decimated part of the French fleet at Mers-el-Kebir in July 1940, an event that seemed to tip the balance in favor of the Germans at this crucial moment of political leveraging. Pétain’s prime minister, Pierre Laval, seized this opportunity to do everything he could to secure “sincere and unreserved cooperation” with Nazi Germany. This was sealed by the infamous handshake between Pétain and Hitler at the French town of Montoire on October 24, 1940. After this event, Pétain delivered what would in retrospect be his most damaging pronouncement: “It is with honor and in order to maintain French unity, a unity ten centuries old, in the framework of a constructive activity of the new European order, that I have today entered the way of collaboration.”12

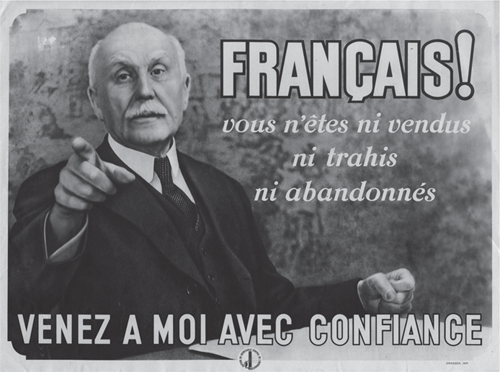

FIGURE 4.1 Philippe Pétain propaganda poster.

Hence revanche, for Pétain at the start of the Vichy regime, had a very particular resonance. The humiliation of the fall of France could be refigured or “spun” as an opportunity to correct the course of France’s destiny, a course that had veered badly off track during the Third Republic. “Enter[ing] the way of collaboration” with the Nazis would not only offer France a new opportunity to join its past (“a unity ten centuries old”) with its future (“the new European order”). It would also allow the nation to wreak revenge upon those elements that had shattered French unity into two distinct halves: left-leaning, democratic elements that could now be purged from the system.

Over the course of four years, however, Vichy policy proved to be markedly less transformative than it proclaimed itself to be in 1940. Pétain’s National Revolution seemed to offer a blueprint for France’s future, and many plans were laid for excising the supposed decadence and rot from French culture. But the practical implementation of this revolution was continually thwarted by internal corruption and dissension as well as by the stark demands of the German occupiers for money, food, and materiel. In fact, the very purposeful agenda of Vichy’s first two years—a revolution at home and voluntary association with Hitler’s Germany abroad—would produce little social change but much social unrest. When the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, a groundswell of communist resistance in France followed by brutal Nazi reprisals turned Vichy into a virtual police state. And when the Nazis occupied all of France in November 1942, whatever useful function the regime served had largely dissipated. By 1943, the thrust of Pétain’s 1940 agenda had been transformed into passivity and the generalized attitude of attentisme: “waiting.”

Ironically, this later posture of Pétain and his administration would serve the postwar defense of the Vichyites: attentisme seemed much more justifiable after the war than the activist agenda of the National Revolution. Thus Yves Bouthillier, Pétain’s minister of finance, wrote after the war that the Vichy regime was not a “clear, logical, and rational construction”; rather, it was driven by the belief that “waiting, as clear-sightedly as possible, was the surest path to safeguard the French future.”13 Or as Pétain defended himself to the French on the eve of the Liberation in 1944: “If I could not be your sword, I tried to be your shield.”14 And Bernard Faÿ, as we shall see, would also invoke the shield metaphor to defend his actions retroactively in his trial for collaboration after the war.

Yet however much these Vichy ideologues used the idea of attentisme as a way of obscuring in retrospect the purposefulness of the National Revolution between 1940 and 1942, it is also true that “waiting” characterized the stance of certain segments of the regime from the start of the war. This could be seen in the varying attitudes of collaborationists toward the Nazi occupiers. While there were some in France—the so-called Paris collaborationists such as Pierre Laval and Fernand de Brinon—who continually sought to strengthen and affirm the unity of France and Nazi Germany, others in the regime were more circumspect, guarded, or desultory in their posture toward the Nazis. Defending, shielding, and waiting seem to have been from the outset of the regime ways of dealing with the occupier and other foreign entities. And waiting could also keep alive conflicting allegiances. It could place France in a holding pattern with uncertain antagonists like Britain. It could also justify surprising relationships, like that between Vichy and the United States.

At once allies and adversaries, France and America performed a strained diplomatic dance throughout the war. The United States did not sever ties with France in June 1940, and both countries continued to maintain diplomatic relations with the other even after America had entered the war against the Axis powers in December 1941. Pétain, according to his confidantes, had a “real passion” for America, stoked by his close personal ties to General John Pershing, with whom he had fought side by side in World War I.15 His instructions to his own representative to Washington, Gaston Henry-Haye, were succinct: “save American friendship.”16 Roosevelt, for his part, understood intrinsically the value of remaining neutral toward France, with the ultimate goal of persuading Vichy to reenter the war against Nazi Germany. His concern to preserve the autonomy of both the French empire and its war fleet, still under the control of the Vichy government, was also of paramount importance. However, Roosevelt’s official line was a carefully constructed humanitarian one, encouraging Americans to think of their old friends the French as wartime victims worthy of aid rather than Nazi fellow travelers. This allowed the United States to offer diplomatic recognition to Vichy and material aid to France and its colonies. Roosevelt only hoped that his neutral stance would encourage restive French elements to rebel. Well into 1941, he was assured by his ambassador to France, William Leahy, that the French “look to you as their one and only hope for release from Nazi rule.”17

Yet Leahy also admitted to Roosevelt in November of that year that Pétain was a “feeble, frightened old man … controlled by a group which, probably for its own safety, is devoted to the Axis philosophy.”18 The overtly pro-German stance of Laval and other Paris collaborationists, along with events such as the Pétain-Hitler handshake at Montoire, made difficult any concrete signs of rapprochement between Pétain and the United States. Trying to play as many angles as possible while avoiding conflict, Pétain sought to steer a mediating course between America and the Nazis, hoping above all for a “compromise alliance against their real mutual danger, communism.”19 Yet his stance of attentisme became increasingly tenuous as the war ground on and as Vichy policy, such as it was, buckled under the sheer brutality of German demands. By the summer of 1942, several months after the Germans had reinstated Laval as prime minister, Roosevelt recalled Ambassador Leahy to Washington, leaving only an American chargé d’affaires to do business with the crumbling Vichy regime. At the same moment, Roosevelt assigned an official representative to Charles de Gaulle’s Committee of National Liberation, prefiguring a crucial if still uncertain shift in support away from Pétain and toward the London-based Gaullist Free French.20

In the end, attentisme tested and eventually poisoned diplomatic negotiations between the United States and Vichy. Henry-Haye, Pétain’s American ambassador, deplored his “thankless” mission to an American government increasingly suspicious of Vichy’s passivity and intractability. Writing in his memoirs, La grande eclipse franco-américaine, Henry-Haye condemned the “tragic eclipse” of Franco-American relations as a result of American perfidy, particularly Roosevelt’s decision to forsake the “authority” and “integrity” of Maréchal Pétain in favor of de Gaulle. It was America’s growing belief in the “criminal compliance of the men of Vichy” with the Nazi regime that shattered whatever trust there was between French and Americans during the war.21 Little mention is made in these memoirs of the fact that the character of Pétain and the “men of Vichy” was rather obscure to outside observers; as a diehard Pétainiste, Henry-Haye, like many of his contemporaries, simply could not understand American suspicions of Pétain’s vaunted integrity.

As Julian G. Hurstfield writes, “many of the mere functionaries of the Vichy regime would survive its demise; none of the true believers did.”22 Gaston Henry-Haye, publicly attacked in the United States as an agent, by proxy, of the Nazis and unable to secure American protection in Paris at the Liberation, defined the character of the Pétainiste true believer. His memoirs about the Vichy regime and its failed mission, published in French in 1972, are bitter and tinged with irony. But they are also remarkably germane to our story. Framed as a dialogue between himself and an anonymous close friend, a “former professor of the Collége de France, who had taught at various American universities … between 1920 and 1940,” Henry-Haye gives an intimate portrait of Vichy and America not only from his own perspective but also from that of his “anonymous” interlocutor, Bernard Faÿ23

As Faÿ feeds Henry-Haye questions about his experience as Vichy ambassador to America—questions designed to flatter and soothe Henry-Haye’s bruised ego—we catch a glimpse of two elderly “true believers” rehashing the painful disappearance of their once cherished ideals of Franco-American conciliation and, above all, of Pétain’s vision of a National Revolution for France. How do we explain the “inhuman feelings” of the Americans toward Vichy, Faÿ asks? They were the feelings of the “megalomaniac” Roosevelt, who “never responded to the confidence which Pétain manifested in regards to the United States,” Henry-Haye answers. How did you deal with American diplomatic treachery and duplicity as Vichy ambassador, asks Faÿ? Henry-Haye: through my “oath of fidelity” to Pétain, and through my refusal to abandon “the cause of the Maréchal.” “What sorrow for such a friend of America” to be treated so badly, exclaims Faÿ “Above all a moral sorrow,” responds Henry-Haye, convinced to the end of American duplicity and moral failing in its dealings with Vichy France.24

Faÿ’s role as sounding board and confidant in Henry-Haye’s memoirs is subtle but significant. Alone, Henry-Haye’s reflections would have seemed the rants of an embittered old man; in chorus with Faÿ, his memoirs serve as a judgment on history. Together, the two make the case for a crucial breakdown in twentieth-century Franco-American relations as a direct result of American failure to understand the Vichy regime. Unable themselves to comprehend the American mistrust of Philippe Pétain and his ideology of attentisme, Faÿ and Henry-Haye present themselves only as unwitting victims of fate, once-central figures who had the bad luck to be on the losing side of history. In neither of their voices is there any sense of personal culpability for choosing to support the Vichy regime and its ideologies. As these memoirs make clear, the defeat of the Vichy regime would do little to alter the belief of both men in the “integrity” of Pétain and in the inherent value of his vision of national renewal. The price they would pay for this loyalty would be steep: postwar dégradation nationale, social marginalization, and, as we shall see in the case of Faÿ, exile from France.

Like Gaston Henry-Haye, like Bernard Faÿ, Gertrude Stein too felt the strong pull of Pétainism. In Wars I Have Seen, a book she began writing in the winter of 1943, finished in 1944, and published in 1945, Stein makes it clear that even Pétain’s ultimate ruin had not much changed her mind about the man. “Pétain was right to stay in France and he was right to make the armistice,” she contends, explaining that “in the first place it was more comfortable for us who were here and in the second place it was an important element in the ultimate defeat of the Germans. To me it remained a miracle” (W 56-57). Elsewhere in Wars Stein seems to misread Pétain’s effort to reclaim power from Laval in the fall of 1943 as a sign of his “republicanism” (that is, support for the principles of the French Republic) and portrays his actions even in 1944 as “really wonderful so simple so natural so complete and extraordinary …like Verdun again” (W 68, 114). These statements, troubling as they are, are utterly consistent with the “political” worldview that Stein adopted in the interwar period. This was a worldview that privileged above all the pleasures of daily living, peace, and “comfort,” regardless of what might be lost in the bargain, and one that justified itself by turning French defeat at the hand of the Germans into a counterfactual thesis that, by losing, the French were really winning. In his 1945 review of Wars, the French Jewish existentialist philosopher Jean Wahl, who was interned in a French concentration camp and who escaped to America in 1942, reproached Stein for this point, describing it as “almost unbelievable in its naiveté”25 Yet Wahl’s would turn out to be largely a solitary critique.26 Most readers of Wars celebrated the book for its stoic tone and had little to say about its unrepentant Pétainism, and to this day the story is praised uncritically for its courage.27

In fact, unlike Faÿ and Henry-Haye, Stein would emerge from the war unscathed by her support for Pétain. When the Phoney War broke out in the fall of 1939, Stein had retreated to her country house in the Bugey, the region of France where she would remain for the rest of the war. “Discovered” by American journalists at the Liberation, Stein was immediately hailed in the postwar press as a survivor and, for the two years remaining of her life, enjoyed a triumphant return of the public admiration she had experienced in America in the 1930s. In France, her rediscovery was of less public import, but then the French had other things on their mind during the period known as the aprés-liberation (Summer 1944-January 1946). For one thing, they were busy seeking retribution from accused Vichy collaborators: from men such as Pétain; Bouthillier; Joseph Darnand, leader of the Milice; and, of course, Bernard Faÿ; and from the enthusiastically pro-German ultras, or Paris collaborationists, including Laval, Fernand de Brinon, and Robert Brasillach, all three of whom were shot to death during the postwar purge. In this politically charged atmosphere, characterized by the central urge “to rebuild a nation and restore its dignity,” the Pétainism of an American expatriate like Gertrude Stein would have been dismissed as an anomaly or at the most subsumed by the larger fact of Stein’s evident personal vulnerability during the war.28

Things might have been different had Stein’s intention to promote Pétain and his National Revolution been more publicly successful. In correspondence during the second year of the Vichy regime, as we shall see, Stein referred to herself as a propagandist for France, but ultimately there was little to show for her efforts. With Faÿ, Stein had planned a second lecture tour of America in the fall of 1939 in order to “be of use to France” (and, it appears, to replenish her dwindling savings).29 This trip was never executed. In early 1941, Stein announced plans to write a book on Vichy for an American audience; this project never took place.30 At the same time, Stein embarked on her now infamous project to publish the speeches of Pétain in English, alongside a glowing introduction; this project was never published. Later in 1941, Stein did manage to publish a pro-Pétainist piece, “La langue française,” in the Vichy journal Patrie. In addition to the pro-Pétainist essay “The Winner Loses,” “La langue française” appears to be the only extant piece of Vichy propaganda Stein actually saw to press during the war.31

Of course, all of these “failures” to support Pétain’s regime raise the question of the strength of Stein’s commitments. Was Stein, like many who lived through the nightmare of the Nazi occupation, simply hedging her bets by trying to make herself as quietly agreeable as possible to the authorities? Was Stein a committed propagandist for Vichy—or a shrewd survivor? Announcing her intentions to be an American propagandist for Pétain was one thing; following through with these intentions was another. In between professed desire and act lay a series of delays, deferrals, and postponements. Plans were changed, rescheduled, “forgotten” in the midst of the privations of everyday life; the war and its likely outcome shifted; and by 1943-1944 the Vichy regime was effectively history. At that point, although her personal vulnerability may in fact have increased, Stein’s effort to be helpful to Vichy would have been irrelevant. What would have mattered—and did—was careful camouflage by supportive friends in the local community around her.

Nevertheless, it appears that for the first two and a half years of the Vichy regime, Stein’s efforts to lend her support to Pétain were both heartfelt and dogged. From 1940 until well into 1943, she continued to write, think about, and give voice to a Pétainist worldview. Even after this point, with Wars I Have Seen, she remained a staunch defender of “her hero.”32 Her commitment may be expressed best in an undated draft of a letter “to the Maréchal” from the Gertrude Stein archives at Yale University. It reads: “To his Verdun, where all shared, with great feeling, his effort and victory. To the even more difficult victory of today, and to his complete success—in admiration and with heartfelt feeling.”33

This letter should not surprise us. After all, for many years before the war Gertrude Stein, with the help and influence of Bernard Faÿ, been sharpening and hardening her critique of the very things Pétain would himself denounce: democratic, liberal, and parliamentary society and the “weak vices” of a decadent modernity. She had agreed with the assessment of Faÿ and others on the Right that a profound political change in both French and American society was needed, that a return to traditional values would be salutary for everybody, and that the reforms promised by fascist and profascist regimes were better than those of communist ones. And she was even convinced that such a change would lead to aesthetic and literary renewal—a renewal already visible in her own experiments in writing. As she puts it in Paris France: “I cannot write too much upon how necessary it is to be completely conservative that is particularly traditional in order to be free” (PF 38).

With the French-German armistice in June 1940, the Stein-Faÿ Collaboration of the 1930s—an intellectual, artistic, and emotional collaboration characterized by genuine affection and mutual political conviction, as well as desire, ambition, and egoism—was transformed into a collaboration of each with the Vichy regime. During this period, Stein and Faÿ had little contact with each other; after the war they would never see each other again. This chapter focuses on the unique wartime experience of Stein, an experience that was spent apart from Faÿ and that would ultimately distance her from Faÿ. Yet this experience was in fact marked by the invisible hand of Bernard Faÿ.

In one of her few letters to Faÿ during the Phoney War, Stein wrote that she was installed safely in her country house at Bilignin and that she was trying to avoid listening to the news, trimming her box hedges, and thinking of ways she could “do something for the good cause.”34 Her book Paris France, dedicated “to France and England,” was one such effort: Stein described it to Faÿ as written “for London,” presumably with the intention of stoking British sympathy for French political maneuvers. Her attempt to return to America for a lecture tour in the fall of 1939 was another such effort, one encouraged by Faÿ. “I went to the Quai d’Orsay,” he writes her in October of 1939, “saw the big man [Minister of Foreign Affairs], and was told … that you could leave France at any time you wanted without difficulty.” Faÿ adds that while “in principle all Americans going back to the U.S.A. are obliged to stay there,” Stein could “be given a ‘visa’ to come back to France as soon as you ask for it.”35 It is clear that neither Faÿ nor Stein seems to have seriously entertained the idea that going to America, and staying there, might in fact be in Stein’s best interests. While Faÿ mentions in this letter that “it might be better to take [a cabin] on an American boat” rather than a French one, “as they are less likely to be torpedoed,” this seems to be the extent of his worries. Only for a brief moment, just after the fall of France in June 1940, do Stein and Toklas appear to have contemplated a trip to Bordeaux for safe passage back to the United States.36 But nothing came of it. This, despite the fact that Stein was patently aware of the exodus of her friends from France (Janet Flanner, Giséle Freund, Virgil Thomson, Man Ray, Balthus), of fearful news from Germany, and of the official warnings by the American ambassador in August 1939 and May 1940 that all American citizens needed to return to the States post haste.37

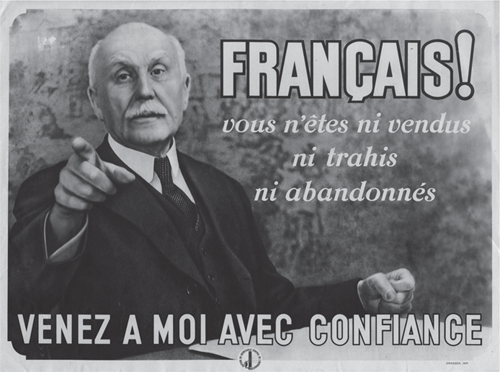

When the armistice was finally signed, Stein writes in “The Winner Loses,” she seemed “very pleased” that hostilities had ceased “and a great load was lifted off France.”38 It is important to note that Stein published these words in the Atlantic Monthly in November 1940, well into Pétain’s regime and well past the point, during the mid-summer of that year, of initial relief at the signing of the armistice. By November 1940, Pétain had shaken Hitler’s hand at Montoire, gone on the radio promoting the idea of collaboration with the Nazis, and been subject to a public demonstration in Paris protesting his regime.39 And he had already, a month earlier, instituted the first “Statut des Juifs”: a decree that for the first time in modern French history defined “the Jew” as a discrete legal entity who could be barred from occupying public and professional posts.40 As Michael Curtis reveals, this decree both preceded and overreached subsequent German anti-Semitic legislation in France: remarkably, “not only can Vichy claim priority in formulating a definition [of ‘the Jew’], but also its formula was more extreme and harsher than the German.”41 Nowhere in Stein’s writing or correspondence during this period is there any mention of the profound anti-Semitism of Pétain’s National Revolution.

By November 1940, indeed, the “great load” that was lifted off France at the armistice had been replaced by the new psychic terror of everyday life under the Vichy regime. Yet as she would do later in Wars I Have Seen, Stein in “The Winner Loses” seems almost willfully intent on interpreting the emergence of Vichy as a positive thing and, even more, as the inevitable fulfillment of a prophecy. Stein’s original title for “The Winner Loses” was “Sundays and Tuesdays”—a direct reference to the significant days of the prophetic saints who guided her through this period. Throughout “The Winner Loses,” Stein acknowledges that she relied heavily on prophetic texts to make sense of the events of 1939-1940, particularly works by the seventh-century Alsatian Saint Odile, as well as by the Curé d’Ars and an English astrologer named Leonardo Blake. Such prophecies “had been an enormous comfort” to her during the uncertainty of the Phoney War and throughout the events of the armistice, Stein writes (WL 144). It was the Curé d’Ars, canonized a saint in 1925, who forecast a French war with Germany that would be resolved by German defeat on successive Tuesdays. Or so Stein thought.42 “The dates the book gave were absolutely the dates the things happened,” Stein claims, at the same moment admitting that these things were not exactly indicative of German defeat (WL 115). In fact, the prophecies were dead wrong: what was supposed to be German defeat in 1940 turned out to be German victory. But the gap between prediction and reality serves only to emphasize Stein’s ultimate will to believe in what the prophecies said. As John Whittier-Ferguson notes, Stein’s wartime writings continually return to “the comforting rhythm of what must be.”43 What matters is her “faith” in a given outcome, despite her own often ironic awareness of the limitations of prophecy. As Stein wrote in a letter to Faÿ from the 1930s, “I take a dark view of life but then I have plenty of faith.”44

In Wars I Have Seen, Stein in fact uses the charged term “faith” to describe her reliance on prophecies during the war. Life in 1940 was not a simple thing, she writes, but she “had to have the prophecies of Saint Odile” in order to have “faith.”45 The term “faith” in reference to Saint Odile raises an issue that has so far been ignored even by Stein’s best readers and critics: her attraction to the predictions of specifically Christian prophets. In her wartime novel Mrs. Reynolds, a single line stands out for its incongruity: “The Jews John Ell said are good prophets.”46 This throwaway line, uttered by a marginal character out of the blue, is the only reference to Jewish prophets in all of Stein’s writing during the war, writing that elsewhere continually refers to the prophecies of the saints Odile, Godfrey, and the Curé d’Ars. Why this preference for the prophecies of saints? What was it that the Christian saints represented for Stein that she found so comforting during the war?

The answer extends back to Stein’s initial attraction to the aesthetics and rituals of Catholic saints and sainthood, discussed in chapter 1. For Stein, saints were extraordinary figures with whom she seems to have felt a deep identification: creative geniuses who simply in their existence brought meaning and significance to the world around them. “Beyond the functions of history, memory, and identity,” the saints of Stein’s early works, such as Four Saints in Three Acts, exist in a kind of pure temporal Now; they are avatars of Steinian modernism and of the immediate and ongoing flux of a continuous present. They are also complex signifiers of a gay or camp sensibility, highly stylized performers who traffic in ecstasy and tragedy. But more than purely aesthetic and performative beings, saints are also inseparable from holiness and religious faith. Again, the religious dimension of saints is not insignificant to Gertrude Stein, and again, we might understand Stein’s interest in saints as part of a complex substitution for a repressed Jewish identity unassimilable within her own continuously retold narrative of self. Simply put, saints allowed Stein to articulate through redirection the “faith” that could not be outwardly claimed.

During World War II, Stein’s interest in saints resurfaced in surprising ways. “Mrs. Reynolds,” she writes in 1941, “liked holiness but only holiness if it is accompanied by predictions. Holiness often is” (MR 35). During the war, Stein too liked her “holiness”—her saints—for what they could do for her, for their predictive, miraculous, and palliative powers. This, despite the fact that the validity of their predictions seemed entirely contingent on how one chose to interpret events; or as Stein wryly puts it in Mrs. Reynolds, “if the weather was set to be fair all the signs that look like rain do not count and if the weather is set for rain all the signs that look like clearing do not count” (MR 80). In short, prophetic outcomes depend upon what one chooses to “count,” upon the signs one chooses to read, and this choice itself determines the significance of the prediction. Yet Stein also seems drawn to the psychic necessity of sheer belief in “what must be,” a belief inextricable from religious faith. If one has faith, then the words and prophecies of the saints must be believed; there is, reassuringly, no room for skepticism.47 As she writes in Mrs. Reynolds: “she began to believe, for which there is no question and no answer” (MR 171). The novel goes on to detail the considerable psychic compensations for unflinching belief: security, collective meaning, purpose, the lessening of fear in the face of arbitrary and unaccountable violence.

As she would often do in her writing, Stein seems to hold in suspension contradictory tendencies—belief and skepticism—in talking about saints during this period. From the beginning of her career as a student in the psychological laboratory of William James, Stein had focused on the likelihood of a “double consciousness” that structured psychic life.48 Her studies of automatic behavior and distraction convinced her that the self was both an automatic agent and had an “extra” consciousness that observed but did not inhibit automaticity. Some forty years later, Stein seems to be performing precisely this kind of double consciousness. Her writings during the Vichy regime reveal a person at once attempting to believe and watching herself attempt to believe. In a curious passage in Wars I Have Seen on science, for example, Stein denies the permanence of ideas of evolution and progress, both of which she associates with that era of decline, “the nineteenth-century.”49 Following on the heels of a discussion of the relevance and rightness of Saint Odile to the twentieth century, this analysis seems to validate the importance in the twentieth century of faith over evolution, prophecy over progress. In an age where “wars are more than ever … it is rather ridiculous so much science, so much civilisation” (W 40). Yet two paragraphs later, Stein refers to William James—one “of the strongest scientific influences that I had”—to validate a truth-claim based not in belief but in knowledge: “the thing that we know most about is the opposition between the will to live and the will to destroy.” Knowing about this opposition seems of a different register from “belief” or “faith”; knowledge here arises from a psychological truth steeped in the “scientific influence” of James, a truth that subsequently allows Stein to explain and affirm the French “will to live” (W 41). Taken as a whole, then, this passage is ironic and ambiguous: twentieth-century faith and the words of the prophets win out over the false ideals of nineteenth-century science and “civilisation,” but in the end it is science that brings us to the truths “we know most about.”

In this and other passages from Wars I Have Seen, Stein’s will to believe is palpable, yet above and beyond it hovers an uncertainty that such a will may “lack the inner soul of faith’s reality,” as James himself would put it in The Will to Believe.50 Mixed together in this way, faith becomes something like a gamble, akin to Pascal’s wager. It is simply a better bet to believe in God and his saints than not to. Moreover, by willing herself to believe in the prophecies of Christian saints, Stein was also taking out an extra insurance policy against the future. For it was indeed only the Christian saints whose words seemed to “count” at this moment and whose prophecies seemed to hold out the possibility of a cure for the sufferings of herself and those around her. Only the Christian saints, and more specifically the French Christian saints such as Odile, Godfrey, and the Cure d’Ars, seemed justified in predicting the outcome of French defeat in 1940.

In the region of the Bugey, where Stein spent the war years, the miraculous doings of Christian saints were as renowned as they had been when the saints were alive and ministering in this rural locale. Catholic piety and local tradition were still deeply and inextricably rooted in the rolling hills around Belley. Little had changed since the Middle Ages, when saints served to reflect and direct the hopes of their society, existing as “the heavy voice of the group” in heightened situations of anxiety or fear.51 In “The Winner Loses,” Stein emphasizes this connection, noting that the predictions of the nineteenth-century Curé d’Ars—originally a priest from a town close to where Stein was living—were “the ones they talked about most in the country” (WL 115). Stein readily adopted the local manner of coping as her own, claiming that she found particular “comfort” in the predictions of the Curé. She even trumped the Catholic faithful in her commitment to the book of prophecies: “and I read the book every night in bed and everybody telephoned to ask what the book said” (WL 115). Stein also had frequent and friendly contact, through the intermediary of her friends Bernard Faÿ and Henri Daniel-Rops, with the monks at the beautiful Hautecombe Abbey, ten kilometers to the east of Belley. Through this contact, one local seminarian brought to life for Stein the prophecies of Saint Odile, translating her original Latin text into French. Although Odile was from Alsace, she evidently changed the way Stein thought about the war. For it was Odile who forecast, as Stein put it in Wars, “the beginning of the real end of Germany, and it is all true, as we all have been cherishing copies of this prophecy ever since 1940.”52 The curious logic of Stein’s conjunction “as”—implying that the truth of Odile’s prophecies lies in the fact that her text is “cherish[ed]”—again underscores the agency of belief so central to Stein’s sense of faith.53

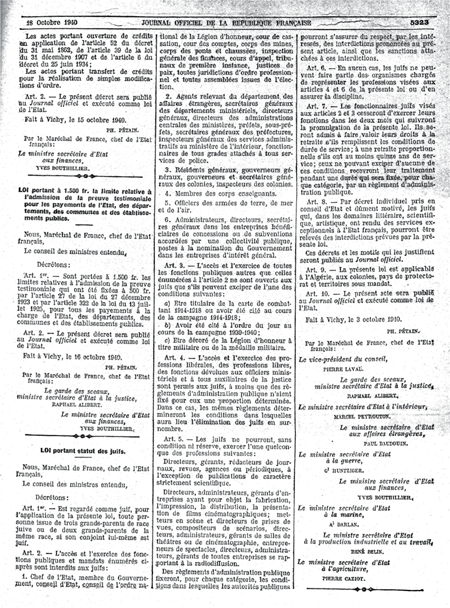

The Christian saints and their prophecies did not just offer “comfort” to the rural French community within which Stein found herself in 1940. Belief in their prophecies was also a matter for her of belonging, of social and political fellow feeling, and hence of safety. For amid this piously Catholic environment and its supportive local networks, one group remained largely voiceless: that of a Jewish population increasingly targeted for purges by the Vichy regime. While southeastern France was until 1942 part of the unoccupied zone and thus free from German legislation, it was not free from the homegrown anti-Semitism of the Vichy regime. During the first two years of the war, Vichy enacted two measures designed toward defining, excluding, and limiting the powers of Jews: the Statut des Juifs of October 3, 1940, that established an official “definition” of Jewishness; and, following the establishment of a Vichy anti-Jewish ministry, the more encompassing Statut des Juifs of June 2, 1941, explicitly designed “to fill lacunae in the earlier law.”54 The thrust of the first statute was to define Jews in exclusionary terms; the thrust of the second was effectively to bar Jews from economic and civic involvement in French life. Deportations to French and eventually German concentration camps, first of foreign and then of French Jews, followed within the space of months. Exemptions were few. In the words of historians Michael R. Marrus and Robert O. Paxton, Vichy “measured exemptions out with an eyedropper.”55

FIGURE 4.2 The 1940 Statut des Juifs (from Journal Officiel de la République française).

FIGURE 4.3 The 1941 Statut des Juifs, announcing census of Jews in unoccupied zone (from Journal Officiel de l’Etat français).

Mysteriously, neither Toklas nor Stein ever appeared on any official Vichy census of the Jews, including the census of the “free” or unoccupied zone of July 1941. “No Jew was dispensed from the obligation to declare himself—not even those exempt from other laws” write Marrus and Paxton of this remarkably thorough census.56 Yet Stein and Toklas remained unaccounted for. Their official invisibility seems to suggest that at least during the first years of the Vichy regime—until the Germans occupied the free zone in November 1942—it is possible, even likely, that Stein was deliberately protected from persecution.57 A story she recounts in Wars I Have Seen is telling in this regard. In the fall of 1942, Stein contemplated a lawsuit against her landlord, a captain in the French army, after learning that she would be forced to move out of her beloved eighteenth-century chateau at Bilignin.58 The substitute house Stein found in early 1943 in the nearby town of Culoz, “quite wonderful even though modern” (W 31), appears to have changed her mind. The account of this story in Wars remains bizarre to this day. What gave Stein the sense of assurance in late 1942 that a lawsuit against her landlord in this charged environment would have no consequences? Was it really the luck of finding equally “wonderful” quarters that made her drop the lawsuit scheme in early 1943? On the next page of Wars, Stein details another, more chilling encounter with her lawyer, who warned her that he had spoken to a Vichy official and that she and Toklas would soon be targeted for deportation to a concentration camp. Stein refused to leave (“here we are and here we stay,” she commented [W 32]), but the move to Culoz seems more than coincidental. What Wars never acknowledges is what presumably took place between late 1942 and early 1943, when Stein was made aware, possibly by Faÿ himself, that dropping the lawsuit scheme and moving to Culoz would be personally expedient.59 By late 1942, the Vichy state could no longer assure Stein and Toklas of protection. Within several months, they were warned by the local subprefect, Maurice Sivan, to flee to Switzerland or risk deportation (W 32). These two elderly Jewish women were now to be at the terrible mercy of the Nazis or of those individuals who took on the risk to protect them.

In many ways, the final two years of the war were likely the most precarious for Stein. After the Nazis invaded all of France in November 1942, they grew increasingly frustrated with Vichy’s failure to expedite the deportation of Jews. During this period, as the Vichy regime crumbled, all pretense of favoritism dropped away, and German demands for Jewish deportations became relentless. The surrendering of the Italian zone in September 1943, where Jews had been relatively safe, meant increased persecution for those hiding in the southeastern region of France, including Stein. After April 1944, the Nazi occupiers in Paris declared “that all Jews, whatever their nationality, were to go.” During the last eight months of 1944, 14,833 Jews were deported from France, including a caravan of 232 children on one of the last convoys to leave for Auschwitz, on July 31, 1944. None of the children survived, a fate that also met the forty-four Jewish children hiding in the tiny village of Izieu, some thirty miles to the south of where Stein was living at the time. Seized and deported to Auschwitz in April 1944, all forty-four children and six of their seven minders were executed. 60

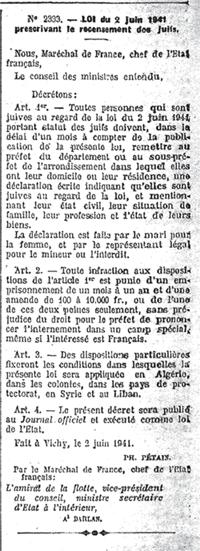

FIGURE 4.4 Stein’s home at Culoz, France.

SOURCE: COPYRIGHT EDWARD BURNS

According to Stein herself, it was the local community that protected and ultimately saved her during the war. In an evocative phrase, Stein refers to herself and Toklas as “rather favored strangers” in their community (W 74).61 After the Liberation in August 1944, Stein told the journalist Eric Sevareid that it was the mayor, the subprefect, and the townspeople who chose to look the other way when official anti-Jewish legislation trickled down to the villages of Bilignin and Culoz. Sevareid reports that it was indeed the mayor of Culoz, Justin Hey, who kept Stein from signing the register of Jews in the town.62 This claim might make sense in the period from 1943 to 1944, when the Bugey region became a stronghold of the French Resistance. Stein clearly manifests support for the Resistance in the latter part of Wars I Have Seen and makes much of this in her postwar writings. Before mid-1943, however, Stein was likely spared by a decision of someone in the Vichy regime—a fact she may not have wanted Sevareid to know. Nevertheless, even in Culoz at the end of the war, as Stein herself wrote in Wars I Have Seen, “everybody knowing that everything is coming to an end every neighbor is denouncing every neighbor, for black traffic, for theft, for this and that, and there are so many being put in prison” (W 23). This acknowledgment adds yet another twist to the mystery around Stein’s survival. Why was Stein somehow exempt from this category of “everybody”? Even if it is true that Stein spent the last part of the war being protected by the locals, the question remains: what was it that these French people saw in their neighbor Gertrude Stein? Why would they have been willing to risk their lives to save her?

The answer to this question may lie in Stein’s unusual position as insider-outsider. Stein was from Paris and was well connected to the local Bugey elite: both signifiers of status in provincial France. She was a famous author, something she seems to associate with her wartime survival in Wars I Have Seen63 She was friendly and endearing to neighbors, sharing an affective bond with her community during her famous walks through town that may have helped her weather the denunciations of “everybody.” But she was also, as her interest in Christian saints suggests, a believer. Someone who attempted to belong, in the deepest sense of sharing and witnessing. Someone who shared with her neighbors a belief in the power of the Christian saints to protect and guide their flock through a terrifyingly uncertain future, and who witnessed with the group the miraculous outcomes of saintly predictions. This neighborliness is recounted in detail in Wars I Have Seen as well as in letters Stein wrote to her friend W. G. Rogers, where she specifically notes that the religious predictions were a conduit for social interaction.64 Combined with a manner cultivated since youth to avoid any outward identification with Jewishness, believing in the Christian saints prevented Stein from being seen as the stereotype of the Jewish “foreigner” disseminated by anti-Semitic propaganda. With her enthusiastic, outspoken efforts to “pass” as a Christian believer, Stein created a bubble of protection around her that spared her, in most instances, the shaming and ostracizing label of “Jew.”

Had Stein refused to accept the shame attached to this label or had she had less complex and uncertain feelings about Jewishness, her fate might well have been different. By aligning herself with the saints, however, Stein moved squarely into the circle of her local community. And given that her Jewishness was the chief thing she needed to hide, Stein’s ability to pass as a Christian believer—however ambiguous, ironic, or layered it may seem in her writing—may well have contributed to her long-term survival.

While the region in southeastern France where Stein lived during the war had been immortalized by Brillat-Savarin as pristine and beautiful, it had yet another, more dubious distinction. In his great early nineteenth-century novel The Red and the Black, Stendhal had described this region as the very embodiment of provincial life, as reactionary and deeply traditionalist, as a place where the “tyranny of opinion” held sway.65 In the Bugey in 1940, there was particularly strong support for Philippe Pétain’s National Revolution; at the outset of the Vichy regime, the region was a bastion of Pétainism. For the farmers and small villagers living in and around Belley, Pétain was “one of us”—a simple man from a rural, farming background who had never lost touch with his roots. Pétainist propaganda that emphasized the value of manual labor, traditional family structures, and faith in the power of authority figures was hugely successful in this region. Support for his regime was stoked in the pages of the local press, including the moderately rightwing Le Bugiste, which interviewed Stein about her Pétainism in 1942.66 There Stein reiterated an argument that she had made several times before, including the previous year in the pro-Vichy journal Patrie (Fatherland): that Pétain was a savior because he had brought peace and “daily living” back to France, a country that was “always in strict contact with the earth” and for whom rural life represented the “essence” of vitality.

Stein would go even further in the propaganda she wrote for Patrie, making an implicit connection between French rural life and a sense of language steeped in the “eighteenth-century”—always a code phrase, as suggested in chapter 2, for a political and aesthetic ideal as yet uncorrupted by the decadence of “nineteenth-century” modernity. In the Patrie piece, Stein suggests that only French peasants speak a “true and pure language,” a language not “denuded of reality.” She uses as an example the phrase of a farmer referring to the end of the day as “the hour when the poets work” and notes that only in rural France could writing be seen as a form of “labor.” The continuity between farm labor and written labor, the emphasis on production rather than consumption, the timeless, vital language of the peasantry, the idea that only people “in contact with the earth” can speak “purely”—Stein’s aesthetic-agrarian utopia here blends seamlessly with a Pétainist ideology of return, reaction, and renewal. Toward the end of this cryptic piece of Vichy propaganda, she writes that rural speech does not confuse itself with formal, written language. Yet in times of war, it appears, formal language prevails over the “purity” of rural speech, because “violent and heroic action creates written language.” In other words, peace encourages an earthbound, vital language to flourish; violent action requires artificial, stilted expression. Finally, the subtext of this essay becomes clear. By restoring “peace” to France with the armistice, Pétain is doing more than simply healing a defeated country. He is also allowing the French language to be led away from abstract formalism—la langue écrite—and back to its spoken, “eighteenth-century” vitality. Pétain’s armistice and his National Revolution are salutary not just for the lives of French people but also for the health of the French language.67

Stein’s argument in the Patrie piece is profoundly reactionary, the essence of reactionary modernism. It recalls the subtext of Stein’s commentary on her own writing during the 1930s. There, Stein often frames her own experimental writing in terms of a similar aesthetic “return” to a language obscured by more than a century of corrupt usage. She uses a retrogressive chronology to describe her “twentieth-century” writing as an aesthetic form that bypasses “nineteenth-century” modes of writing in favor of “eighteenth-century” ideals. In her 1934 lecture “The Gradual Making of The Making of Americans,” for example, Stein explains how her “twentieth-century” interest in paragraphs allows her to rediscover an “eighteenth-century” focus on sentences: “I have explained that the twentieth century was the century not of sentences as was the eighteenth not of phrases as was the nineteenth but of paragraphs,” she writes, suggesting at first a distinction between the writing of her own and previous epochs. But in the passage immediately following such a distinction breaks down: “In fact inevitably I made my sentences and my paragraphs do the same thing, made them be one and the same thing. This was inevitably because the nineteenth century having lived by phrases really had lost the feeling of sentences.”68 Making the twentieth century (the period of paragraphs) and the eighteenth century (the period of sentences) “be one and the same thing,” at least in writing, allows for the “losses” of the nineteenth century to be overcome. Elsewhere, Stein writes that “You had to recognize that words had lost their value in the Nineteenth Century, particularly towards the end, they had lost much of their variety, and I felt that I could not go on, that I had to recapture the value of the individual word, find out what it meant and act within it.”69 Recapturing the “value” of words lost to the depredations of the nineteenth century was a way, Stein writes, to make her writing “exact, as exact as mathematics.” Only by returning to the essence or “value” of a word could this “eighteenth-century” exactitude be achieved.70

Stein reiterates this calculus of century-identity when she provides a gloss on her famous phrase “a rose is a rose is a rose”: “I think that in that line the rose is red for the first time in English poetry for a hundred years.”71 Eighteenth-century roses were red: their essence remained the same across time and context. Nineteenth-century roses, functioning within the force field of modernity and the imperatives of realism, had become empty clichés. The rose in the twentieth century, the rose in the hands of Gertrude Stein, brings us back to what she would call the “value” of the word itself. As we saw in chapter 2, Stein’s invidious distinction between these loosely defined periods of the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries was in the 1930s as yet relatively inchoate. The Patrie piece shows how the emergence of Vichy and its reactionary Pétainist “Revolution” gave Stein a new way to link her nostalgia for the eighteenth century to a political blueprint for social change. Now in 1941, Stein envisions a productive continuity between the political and cultural project of Pétain’s National Revolution, her own experimental writing, and an eighteenth-century linguistic ideal lost to the corruptions of nineteenth-century modernity yet still visible in the primitive, vital language of the French provincial “folk.”

Equally importantly, Pétain’s National Revolution also allows Stein an alternative political vision to that of contemporary, Roosevelt-era America. It was, after all, the “eighteenth-century passion for freedom” that Stein found so deplorably absent in the America she visited during her lecture tour of 1934-1935. In the 1930s, she repeatedly laments the decline of the American agrarian ideal embodied in the worldview of the founding fathers and places the blame firmly on the liberal and mass-oriented “reform movements” of the monstrous Roosevelt administration, which had “enslaved” a pioneering people through “organization.” “Organization,” Stein writes in 1936, “is a failure and everywhere the world over everybody has to begin again … perhaps they will begin looking for liberty again and individually amusing themselves again and old-fashioned or dirt farming.”72 What better model for this renewed society than Pétain’s France? In the introduction to the speeches of Maréchal Pétain that Stein wrote late in 1941, she indeed forges a surprising connection between American agrarianism, the founding fathers, and Pétain’s National Revolution. There, as we shall see, Stein figures Pétain as the living embodiment of an eighteenth-century American ideal hidden beneath what she called the “catastrophe” of FDR’s administration.73 And she chides Americans for not “sympathiz[ing]” with Pétain’s regime, thus losing the opportunity to appreciate Pétain’s leadership in a way that might see them through their own trauma after Pearl Harbor.

Through an intricate combination of critique, idealism, nostalgia, and Franco-American doubling, Stein makes her case for why Pétain’s speeches should appeal as much to the Americans as to the French. A vote for Pétain, she argues, would be a vote for America: not for the “corrupt” America of FDR but for a renewed, revitalized, pioneering, individualistic America long buried beneath the degenerate, robotic frenzy of modern life.

Stein reports that her Belley friends were “all Croix de Feu”—members, informally or not, of one of the most influential French leagues of the extreme Right in the 1930s. These friends may be the individuals whom Stein is referring to when she writes in Everybody’s Autobiography, “we liked the fascists.”74 Like their predecessors from the 1920s, the Faisceau, the Croix de Feu “actively advocated the overthrow of the Third Republic in order to install a new regime”; many of their members would assume roles in the coming Pétain administration.75 Stein makes reference to these friends as early as 1936 in the series she wrote for the Saturday Evening Post. Comparing the spendthrift American Congress under FDR to the Chamber of Deputies in Third Republic France, Stein writes:

In France the chamber has been doing the same thing spending too much money and so everybody voted for the communists hoping that the communists would stop them. Now everybody thinks that the chamber under the communists will just go on spending the money and so a great many frenchmen are thinking of getting back a king, and that the king will stop the french parliament from spending money.76

The “great many frenchmen” Stein refers to are never identified, but according to historians few modern French people saw the return of the monarchy as a viable political alternative, even at the end of the Third Republic.77 Stein’s claim is thus clearly an exaggeration, yet what is interesting is her familiarity with the monarchist critique. According to Samuel M. Steward, Stein even argued that “I think it takes a monarchy, needs a monarchy, to produce really good writers, really I do, at least in France.”78 It is likely that Stein’s familiarity with this critique arose both from her conversations with Bernard Faÿ and from the locale where she was living at the outbreak of war.

At least some of those in Stein’s orbit would surely have been involved in a nearby institution located directly south of her home in Belley: the leadership school at Uriage. Nestled in a chateau on a dramatic cliff outside the city of Grenoble, Uriage was one of the ideological centers of Pétain’s National Revolution. It was at Uriage that a group of youthful, idealistic, visionary men, all staunch supporters of Pétain, all highly critical of the French Third Republic, met and founded a school that would “create the guidelines of, and the leaders for, a post-liberal and post-Republican society.”79 Among their ranks were the founder of Le Monde, Hubert Beuve-Méry, and the militiaman Paul Touvier, infamous for his Vichy-era persecution of the Jews.

In his fascinating study of the leadership school at Uriage, the historian John Hellman has traced the lines of convergence between the idealism of these “shock troops” of the Vichy regime and their counterparts in Hitler’s Germany. Hellman argues that Uriage represents a genuine, homegrown example of French fascism, one that saw itself running on a track parallel to Nazism. With their antidemocratic, antiparliamentary stance, their outrage at France’s perceived military and moral weakness, and their elitism, the men of Uriage shared a conservative revolutionary ideology with the Nazis. Like the Hitler Youth, the Uriage men adhered to a doctrine of physical toughness, moral probity, and aggressive patriotism: authoritarianism and strict mental and physical discipline were their guides. In their monastic setting almost completely devoid of women, the men of Uriage imagined themselves as “knight-monks of Vichy France,” thus differing in one significant respect from the Hitler Youth: they were piously, fervently, and above all politically Catholic. Emerging out of the polarized atmosphere of the 1930s, their role models were the militant revolutionaries of the Faisceau movement of the 1920s; the intellectual radicals of Action Française, who traced the spiritual decadence of modern France to the decline of the Church after 1789; and the Catholic “personalist” philosophers of the early 1930s, with their calls for a “reform of the spirit.” Their moment arrived with the advent of the Vichy regime in 1940, whose core conservative Catholic ideology informed and reflected the vision of Uriage. “To live in a community in the spirit of the National Revolution” became the “official objective” of the school, which continued its mission until the Germans occupied the south of France in late 1942. After this point—in a transition typical of other such “gray zones” in Vichy France—a good number of Uriage members stepped up to join the French Resistance.80

While Stein had no explicit connection to Uriage other than geographical proximity, she had indirect ties, notably through her close friendship with a French personalist philosopher named Henri Daniel-Rops. Still known today for his best-selling religious writings, including a multivolume History of the Church and many accounts of the lives of saints, Daniel-Rops was active during the 1930s in the French movement that sought to merge personalist philosophy with a political “third way” between Soviet-style communism and American-style capitalism. His work on behalf of a group called Ordre Nouveau (New Order) produced among other pieces an infamous 1933 essay, “Letter to Hitler,” in which he and his colleague Alexandre Marc set out the blueprint for a specifically French national socialism that would in part derive from Hitler’s own. Their credo was unsparingly national socialist: “We believe that at the spiritual origin, if not in the tactical evolution, of the national socialist movement, is to be found the seeds of a new and necessary revolutionary position.”81 Such a “necessary revolutionary position” was to be grounded in an elite corps of chivalric men who would be trained to embody and propagate this national socialist ideal. Seven years later, the training school at Uriage came into being, a living embodiment of the unholy alliance between French personalist philosophy and German-inspired National Socialism.

Not surprisingly, Daniel-Rops was a regular lecturer and guest at the school of Uriage during the war.82 He was also a frequent guest of his neighbor Gertrude Stein, whom he probably met at the home of their mutual friends, the Pierlots. Throughout the war, Stein and Toklas seem to have spent much time in the company of the endearingly odd person they called “Rops” and his wife Madeleine, referring to them as “the nicest french couple we have ever known.”83 Stein would also make flattering remarks about Daniel-Rops in Paris France and in letters to friends, where he was invariably portrayed as a picturesque intellectual and sympathetic neighbor, if hardly himself an example of the virile, strenuous masculinity he championed in his Ordre Nouveau writings.84

But Daniel-Rops’s political connections were also not without interest to Stein. Along with another neighbor, Paul Genin, Daniel-Rops appears to have been instrumental in facilitating Stein’s efforts to produce propaganda on behalf of the Vichy regime. In the Stein archives at Yale University, there is an undated document written in the distinctive hand of Daniel-Rops: a letter to the prefect of the region outlining a rationale for granting Stein a driving permit. Presenting Stein as a “writer and journalist,” Daniel-Rops argues for the necessity for Stein herself to see “all the magnificent efforts that are currently being accomplished” in order “for America to know exactly [about] the new France.” He notes that Stein has been asked “by the American press” to write a series of articles on “the reconstruction of France.” And he claims that Stein’s work is supported by “considerable French writers,” of which “one name only” need be cited, that of Bernard Faÿ Daniel-Rops adds that Faÿ “would give information on the work and the importance of [Stein’s] influence on public opinion in the United States.”85

The idiom of this letter, and the substantive corrections to it in the hand of Alice Toklas, suggest that it was composed directly by Daniel-Rops. Yet it is also likely that if Daniel-Rops was not directly translating, he was mostly facilitating an initiative begun by Stein herself. In the same archival box reside two earlier letters to the prefect asking for driving privileges, all written by Stein herself. In the first of these, dating from April 1941, Stein announces that she has “been asked urgently to prepare a book on France for the United States.”86 Ten days later, Stein impatiently makes her position clearer: “Mister the prefet [sic], You accorded me certain privileges as an American writer working for French propaganda in America and now the book I wrote about France at war is now out in America and is having a great success, I am now asked to continue [during] France’s last defense, this is of great importance for French propaganda in America.”87 Stein’s insistence on her role as Vichy propagandist and reference to the “great success” of Paris France apparently fell on deaf ears; none of her special requests seems to have been granted, as she notes in successive letters. In the face of this frustration, Stein must have asked Daniel-Rops to assist her in writing to the prefect on her behalf.

This sequence of letters of early 1941 tells us much about how Stein perceived her position in World War II France. In her public self-presentation, in her appeal for help to Daniel-Rops and other Pétainist neighbors in the region, and in her official invocation of the name of Bernard Faÿ Stein shows no qualms about presenting herself as sympathetic to the regime. While we might want to assume that Stein was attempting to manipulate a system she secretly reviled, the archival evidence gives us no way to validate that assumption. On the contrary, Stein’s own words portray her as a “propagandist” for the “new France.” Her letters ask for privileges, but they do so in the name of commitment to and belief in the maréchal. Her letters also make it clear that Stein had already received privileges “as an American writer working for French propaganda in America.” Much of this would become obvious once Stein took on the project of translating Pétain’s speeches into English in December 1941 and of introducing his National Revolution favorably to an American audience. But with the Daniel-Rops episode many months earlier, we are able to see Stein already fully, and apparently willingly, participating in the Vichy propaganda machine.

Another document found in the same archival folder as the Daniel-Rops letter adds yet one more tantalizing insight into Stein’s support for Vichy during early 1941. Dated May 2, 1941, it is a letter from a General Benoît Fornel de La Laurencie to Admiral Darlan, commander of the French Armed Forces under Vichy. Written in French, the letter details La Laurencie’s dismay at having been dismissed from the National Council by Darlan for having shown positive leanings toward Britain and America. La Laurencie freely admits to “anglophilia” and to his desire for an Anglo-American victory over a German one. But he argues that he has never wavered in his support for Maréchal Pétain and has “always rigorously abstained from the risk … of compromising the authority of the government.” The letter ends with La Laurencie’s bitter hope that his actions in support of both Vichy and the Anglo-American alliance—actions that have undermined his career—may ultimately one day be proven justified.88

What was this letter doing in Gertrude Stein’s possession? What could this internal Vichy affair possibly mean to Stein? This letter can only have been given to Stein by the same person who arranged for the Pétain translation project in December of 1941: Bernard Faÿ. La Laurencie was fervently anti-Masonic and moved in the same collaborationist circles as Faÿ.89 He had also been instrumental in disrupting the career of one of Faÿ’s chief Vichy rivals, Marcel Déat.90 In the tight-knit world of Vichy, La Laurencie and Faÿ were natural allies. But what would he have meant to Stein? What was she meant to do with his letter?

Obviously, there are similarities between the attitudes of La Laurencie and Stein herself. La Laurencie was what one critic has called a “Vichysto-resistant”: pro-Vichy but suspicious of the Germans.91 Adept at negotiating tense but not untenable relationships, he pledged loyalty at once to Pétain and to the Anglo-American cause.92 In fact, La Laurencie, rather than de Gaulle, had long been favored by the American ambassador William Leahy as the man to bring France back into the war against the Nazis. He had been instrumental in the December 1940 coup against Pierre Laval and had been blackballed by the Germans as a result. Yet he was also a Pétainist and a key player in the inner circle of Vichy politics. Perhaps, then, La Laurencie’s letter was meant to reassure Stein that a pro-Pétain/pro-American stance was both feasible and desirable. Perhaps it was also meant to stoke her investment in Vichy-American relations. But in this case it is likely that the letter was given to her by Faÿ for instrumental purposes—for her to translate or somehow disseminate as propaganda to an American public increasingly skeptical of Vichy’s aims and integrity. This, of course, would be the point of Stein’s Faÿ-initiated project to translate Pétain’s speeches into English some months later: convincing the American public that Pétain’s National Revolution was a cause worthy of both support and emulation.

Was Stein aware that there was a more sinister side to Général de La Laurencie? For it appears that he was not only anti-Masonic but also anti-Semitic—or at least an enthusiastic supporter of Vichy racial policy. In 1940, in the wake of the first official German anti-Jewish decrees, it was Général de La Laurencie, as Vichy delegate to the Nazi occupied zone, who would urge local prefects to go beyond the letter of the law in collaborating with the required census of Jewish enterprises. He writes in a memo to prefects that they must “use … all means of information at your disposal toward a supervision designed to assure you that the census has no omission.” The général especially urged prefects to be aware of “the importance of the task incumbent upon them to accomplish.” The zeal of the général’s demand was seen in his threat to impose “grave sanctions” on administrators who failed to follow through on the anti-Semitic measures.93

FIGURE 4.5 Général Benoît Fornel de La Laurencie (1939–1940).

SOURCE: RIGHTS RESERVED, COLLECTION CEGES, PHOTO 72110

Most likely Stein knew nothing of La Laurencie other than what is contained in his letter to Darlan. Yet his anti-Semitic activities emphasize yet again the danger of the political world that Stein was trying to negotiate in 1941. It was precisely the zealotry of a man like La Laurencie that would undermine Stein’s careful efforts to avoid being defined, first and foremost, as a “Jew.” However strong her support for Pétain, however supported and protected by Vichy insiders and Belley Pétainists, Stein was still an outsider to his regime, an uneasy exception to the rule: a “good Jew.” And however much she thought herself capable of controlling her fate as a willing propagandist, Stein’s position was still deeply insecure at best. Yet despite all of these dangers and uncertainties, and even after Vichy had ceased to be a viable political entity, Stein remained its unlikely collaborator.

At the end of 1941, Stein undertook a project to translate the speeches by Philippe Pétain that had been collected in a book edited and introduced by Gabriel-Louis Jaray, a friend of Bernard Faÿ.94 It was no small endeavor. For the next year and a half, Stein translated some thirty-two of Pétain’s speeches into English, including those that announced Vichy policy barring Jews and other “foreign elements” from positions of power in the public sphere and those that called for a “hopeful” reconciliation with Nazi forces. The last of Pétain’s speeches that Stein translated was from August 1941, but Stein did not cease working on the project until January 1943—several months after the Germans had occupied the whole of France in November 1942 and long after the United States had entered the war against the fascist forces that Stein was promoting to her fellow Americans.

The Pétain translations to this day remain unpublished, tucked away in the Stein archives at Yale University: several manuscript notebooks, a few typed pages, and the typescript of the introduction that Stein wrote to accompany the translations. The first speech translated is Pétain’s address of 1936, delivered at the inauguration of a monument to the veterans of Capoulet-Junac; the last, Pétain’s 1940 Christmas address. Stein followed the erratic chronology of the original text, Paroles aux français, messages et écrits 1934-1941, translating approximately the first half of the fifty speeches published. Still, she leaves some speeches untranslated, and it is interesting to speculate as to why. Speeches discussing the education of French youth, regional administration, and French legionnaires may have been deemed irrelevant to the kind of popular American audience that Stein was ostensibly trying to court, but Stein also leaves untranslated a speech on Franco-Canadian relations that argues for cross-cultural understanding and a speech announcing Pétain’s desire to form a Supreme Court “as is found in the United States.” Whether or not these omissions were deliberate, they raise a central question: was Stein herself involved in the selection of these translations, or was she a mouthpiece for someone else’s directives?

Stein’s notoriously bad handwriting is especially pronounced on these pages, and the manifold corrections in the hand of Alice Toklas only exacerbate the difficulty of reading. But what is most striking about the text is its almost stupefyingly literal rendering of the French original. Translating word by word, Stein completely ignores questions of idiom or style: “Telle est, aujourd’hui, Français, la tâche à laquelle je vous convie” becomes “This is today french people the task to which I urge you.” An idiomatic phrase such as “Le 17 juin 1940, il y a aujourd’hui une année” becomes “On the seventeenth of June 1940 it is a year today.” “Ils se méprendront les uns et les autres”—a speech denouncing Pétain’s critics—is translated “But they are mistaken the ones and the others.” Syntax is distorted: a speech describing the refugees from Lorraine notes the abandonment of “le cimetiére où dorment leurs ancêtres”; Stein translates this as “their cemeteries where sleep their ancestors.” Even the term “speech” is avoided: “Discours du 8 juillet” becomes “Discourse of the 8 July.”

Stein told W. G. Rogers that she hoped to interest the Atlantic Monthly in this translation project, presumably imagining it as a further extension of the pro-Pétainist line she had put forth in the 1940 Atlantic Monthly essay “The Winner Loses.”95 But if Stein’s goal was to familiarize an American audience with Pétain’s words, these translations seem incongruous, even inept. They are arguably the work of a writer with little or no real familiarity toward the foreign language being translated. Alice Toklas’s corrections—more copious and directive than in other of Stein’s texts she copyedited—affirm this assessment of Stein as a bungling student reaching beyond her linguistic depth. Yet the weakness of the translations seems to belie Stein’s fluency as a reader and relative fluency as a writer of French at this point in her life.96 Not only had Stein long been a reader of French—her early reading of Flaubert’s Trois Contes had famously informed her experimental text Three Lives—but she had recently finished an original composition in French (Picasso, 1938). More than a decade before the Pétain translation project, moreover, she had felt confident enough to embark on a translation into English of a text that would even stretch the skills of a Francophone: the poem cycle Enfances by the French surrealist poet Georges Hugnet. This translation would ultimately appear as one of Stein’s most hermetic published works, Stanzas in Meditation.97

Hence the striking literalism of Stein’s Pétain translations seem to point to a deeper issue than linguistic ineptitude. It suggests that something profound has happened to a writer whose most experimental work, like Stanzas in Meditation, interrogates, and ultimately celebrates, the shifting, unstable relationship between words and meanings, signifiers and signifieds. In the Pétain translations, Stein’s attempt to render the French original into English through a one-to-one correspondence between signs seems to be conceding authority, interpretation, and interrogation to the voice of Pétain. This compositional submissiveness suggests a subject in thrall to the aura of a great man: the savior on a white horse, as Stein describes Pétain in her introduction to his speeches. In an interview with her local paper Le Bugiste in 1942, Stein is in fact described in a curious state of ravishment: “she abandons herself to her subject, to her hero, she admires the importance of his words and the significance of the symbol.”98 To invoke Susan Sontag: Stein appears “fixated” or “fascinated” by Pétain, mesmerized and rendered passive by an almost masochistic desire for the figure of the authoritarian dictator.99